Abstract

The balance between spending on children and spending on the elderly is important in evaluating the allocation of public welfare spending. We examine trends in public spending on social welfare programs for children and the elderly during 1980–2000. For both groups, social welfare spending as a percentage of gross domestic product changed little, even during the economic expansions of the 1990s. In constant dollars, the gap in per capita social welfare spending between children and the elderly grew 20 percent. Unlike spending for programs for the elderly, spending for children’s programs suffered during recessions. Public discussion about the current imbalance in public spending is needed.

Recent budgetary proposals continue to transfer federal responsibility for social welfare programs to the states. The passage of the 1996 Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act (PRWORA) marked a dramatic shift in social policy by ending standard entitlement to public assistance for low-income children and families and by devolving federal oversight of traditional welfare mechanisms to the states.1 There are now proposals to turn Medicaid, the single largest insurer of U.S. children, from an entitlement with an open-ended funding commitment from the federal government into a state “block grant” with a predetermined allotment of federal funds that would also allow states to cap enrollment and spending for optional programs within Medicaid.2 In contrast, Social Security and Medicare are federally administered through trust funds buffered from short-term economic fluctuations.

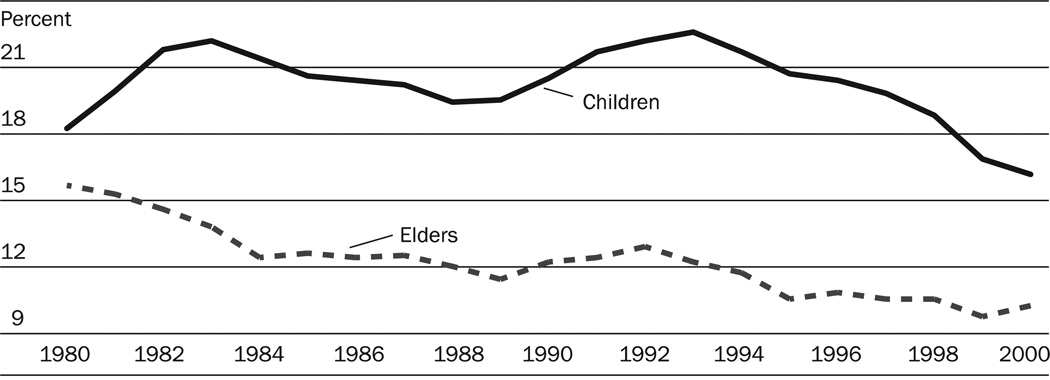

In comparison with other countries, social indicators for U.S. elders are quite good, whereas indicators for children are poor, and evidence suggests that social welfare spending can, to some extent, reduce poverty.3 Despite recent declines, U.S. child poverty rates are among the highest in the world.4 Over the past twenty years, the absolute number of children living in poverty has been nearly three times the number of elderly living in poverty, and poverty rates for children have consistently exceeded those for the elderly (Exhibit 1).5 In spite of these discrepancies, recent and anticipated increases in the number and proportion of U.S. elderly have been accompanied by a “graying” of the federal budget.6 For example, the 2004 Medicare trustees’ report projects that Medicare spending will grow from 2.6 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) in 2003 to 7.75 percent in 2035.7 In contrast, U.S. social spending devoted to children, including health care, is among the lowest in the world.8

EXHIBIT 1.

Percentage Of U.S. Children And Elders Living In Poverty, 1980–2000

SOURCE: U.S. Bureau of the Census, Current Population Survey, Annual Social and Economic Supplements, Poverty and Health Statistics Branch/HHES Division, “Table 3. Poverty Status of People, by Age, Race, and Hispanic Origin: 1959 to 2002,” Historical Poverty Tables, www.census.gov/hhes/poverty/histpov/hstpov3.html (21 June 2004)

In a 1991 study, Ted Benjamin and colleagues found that during the recession of the early 1980s, real spending on children declined, and spending on the elderly grew modestly. They concluded that “during times of economic downturn or stagnation combined with government fiscal crisis…programs for children are hit much harder by the budgetary axe than programs for the elderly.”9 In this study we evaluate trends in social welfare spending for children and the elderly from 1980 to 2000 and the relationship of national economic trends to social welfare spending patterns.

Study Data And Methods

Methods

Following the approach of Benjamin and colleagues, we examined the major components of public social welfare spending that directly benefit children and the elderly.10 Generally, we considered children to be those younger than age eighteen, and the elderly, those older than age sixty-five. For programs that directly benefit children, we included primary and secondary education (K–12), Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) and Emergency Assistance/Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), other child welfare, nutritional support, maternal and child health programs, medical spending under Medicaid and the State Children’s Health Insurance Program (SCHIP), and those portions of Social Security payments (Old Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance [OASDI] and Supplemental Security Insurance [SSI]) that benefit children. For programs that directly benefit the elderly, we included medical spending under Medicare and Medicaid, Older Americans Act expenditures, veterans’ and railroad workers’ pensions, and those portions of Social Security (OASDI and SSI) and food stamps that benefit the elderly.11 Private social welfare expenditures, such as those from philanthropic organizations, and indirect social welfare benefits, such as those provided through the tax system, were not included. In cases where data sources were discrepant or not up to date, we contacted the relevant government agency and individuals responsible for producing annual statistical reports to obtain the most recent and accurate data. Total social welfare spending was calculated as the sum of all relevant components for both groups.

Expenditures were adjusted to 2000 U.S. dollars using the medical component of the Consumer Price Index (CPI) for Medicaid, Medicare, and SCHIP and the overall CPI for all other programs.12 National economic trends were classified as follows: 1980–1984 recession, 1985–1989 growth, 1990–1994 recession, and 1995– 2000 expansion. Unlike expansion, inflation is present during periods of growth. To relate changes in per capita spending to national economic trends, percentage changes were calculated for each time period.13 Per capita social welfare spending for children and that for the elderly were analyzed separately.

Data sources

Data on primary and secondary education are from the 2001 Digest of Education Statistics and the National Center for Education Statistics.14 Data on TANF/AFDC, Social Security, SSI, and veterans’ pensions are from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Social Security Administration and Department of Veterans Affairs.15 Railroad retirement and Older Americans Act data are from the U.S Railroad Retirement Board and volumes compiled for the U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Aging.16 Data on food stamps; Women, Infants, and Children (WIC); and child nutrition are from the U.S. Department of Agriculture. 17 Data on other maternal and child health programs and child welfare are from the HHS Administration for Children and Families. Medicaid, SCHIP, and Medicare data are from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). Poverty and population data are from the U.S. Bureau of the Census. CPI, medical CPI, and GDP data are from the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Findings

Distributional spending

The distribution pattern of social welfare spending on children and the elderly changed little from 1980 to 2000 (Exhibit 2). Education constituted the bulk of public spending for children over this period; it grew from 70.3 percent of total social welfare spending on children in 1980 to 81.2 percent in 2000. Children’s income assistance provided through AFDC (renamed TANF in 1996) represented the second largest portion. The decline in the relative proportion of funds devoted to income assistance and in the real dollar value of total spending in this area occurred predominantly after the passage of the 1996 PRWORA (Exhibit 3).18 There were declines in total food-stamp spending on children after 1996 and in the real dollar value of monthly food-stamp benefits. For the elderly, Social Security and Medicare represented the majority of social welfare spending distribution from 1980 to 2000, and spending in both areas grew consistently.

EXHIBIT 2.

Distribution Of Social Welfare Spending For Children And Elders, 1980 And 2000

| Spending on children (%) |

Spending on elders (%) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Program | 1980 | 2000 | Program | 1980 | 2000 |

| Lower education | 70.3 | 81.2 | Social Security | 58.7 | 61.7 |

| TANF/AFDC and Emergency Assistance | 9.1 | 2.3 | SSI | 1 | 0.6 |

| Social Security dependent benefits (OASDI) | 1.4 | 1 | Railroad retirement | 2.5 | 1.3 |

| SSI for children 0–17 | 0.3 | 1.1 | Veterans’ pension | 1.7 | 1.1 |

| Food stamps | 4.5 | 2.4 | Food stamps | 0.5 | 0.2 |

| Child nutrition (school food programs) | 2.6 | 1.6 | Medicare | 27 | 29.7 |

| WIC | 0.5 | 0.9 | Medicaid | 8.1 | 5.2 |

| Medicaid | 3.9 | 5 | Older Americans Act | 0.5 | 0.2 |

| SCHIP | 0 | 0.6 | |||

| Maternal and child health | 0.7 | 0.6 | |||

| Child welfare | 0.6 | 0.1 | |||

SOURCES: Authors’ analyses of data from the following sources: Data on primary and secondary education are from the 2001 Digest of Education Statistics and the National Center for Education Statistics. Data on Temporary Aid for Needy Families (TANF)/Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC), Social Security, Supplemental Security Income (SSI), and veterans’ pensions were obtained from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Social Security Administration and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Data on railroad retirement and the Older Americans Act were obtained from the U.S Railroad Retirement Board and volumes compiled for the U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Aging. Data on food stamps; Women, Infants, and Children (WIC); and child nutrition are from the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Data on other maternal and child health programs and child welfare were obtained from HHS, Administration for Children and Families. Data on Medicaid, the State Children’s Health Insurance Program (SCHIP), and Medicare were obtained from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Full bibliographic information is available in an online appendix, content.healthaffairs.org/cgi/content/full/23/5/131/DC1.

NOTES: Figures are expressed as a percentage of total social welfare spending on children or elders in a given year. For example, education accounted for 70.3 percent of total social welfare spending on children in 1980. OASDI is Old Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance.

EXHIBIT 3.

Spending On Social Welfare Programs For Children And Elders, Millions Of Dollars, Selected Years 1980–2000

| Children | 1980 ($) | 1984 ($) | 1988 ($) | 1992 ($) | 1996 ($) | 2000 ($) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary/secondary education | 197,385 | 206,106 | 244,778 | 286,692 | 315,334 | 372,865 |

| TANF/AFDC and Emergency Assistance | 25,417 | 23,714 | 24,291 | 26,467 | 22,594 | 10,490 |

| Social Security (OASDI) | 21,421 | 17,415 | 16,368 | 16,607 | 18,687 | 19,335 |

| SSI | 758 | 961 | 1,457 | 3,280 | 4,979 | 4,866 |

| Food stamps | 12,659 | 10,183 | 12,646 | 20,822 | 19,576 | 11,106 |

| Child nutrition | 7,369 | 6,074 | 6,108 | 6,563 | 7,113 | 7,557 |

| WIC | 1,483 | 2,270 | 2,595 | 3,174 | 4,037 | 3,981 |

| Medicaid | 10,970 | 9,907 | 11,187 | 20,248 | 20,099 | 23,000 |

| SCHIP | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2,781 |

| Maternal and child health | 1,817 | 1,753 | 2,445 | 2,574 | 2,480 | 2,654 |

| Child welfare | 1,630 | 270 | 346 | 335 | 304 | 292 |

| Total social welfare for children | 280,909 | 276,899 | 322,219 | 386,759 | 415,205 | 458,927 |

| Elders | ||||||

| Social Security (OASDI) | 223,300 | 269,617 | 296,903 | 332,712 | 361,486 | 388,096 |

| SSI | 3,694 | 3,277 | 3,492 | 3,604 | 3,636 | 3,775 |

| Railroad retirement | 9,638 | 9,973 | 9,637 | 9,403 | 8,893 | 8,303 |

| Veterans’ pension | 6,529 | 7,489 | 6,689 | 6,915 | 6,731 | 6,774 |

| Food stamps | 1,738 | 937 | 1,113 | 1,548 | 1,529 | 1,092 |

| Medicare | 102,651 | 129,758 | 138,090 | 148,447 | 165,526 | 186,649 |

| Medicaid | 30,696 | 31,906 | 32,778 | 40,630 | 42,327 | 33,000 |

| Older Americans Act | 2,023 | 1,838 | 2,220 | 1,519 | 1,315 | 1,284 |

| Total social welfare for elders | 380,270 | 454,795 | 490,924 | 544,778 | 591,444 | 628,973 |

| Total social welfare—children and elders | 661,179 | 731,694 | 813,143 | 931,538 | 1,006,649 | 1,087,899 |

| GDP | 5,695,740 | 6,430,136 | 7,374,289 | 7,722,592 | 8,563,592 | 9,872,900 |

SOURCES: Authors’ analysis based on data from the following sources: Data on primary and secondary education are from the 2001 Digest of Education Statistics and the National Center for Education Statistics. Data on Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF)/Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC), Social Security, Supplemental Security Income (SSI), and veterans’ pensions were obtained from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Social Security Administration and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Data on railroad retirement and the Older Americans Act were obtained from the U.S Railroad Retirement Board and volumes compiled for the U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Aging. Data on food stamps; Women, Infants, and Children (WIC); and child nutrition are from the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Data on other maternal and child health programs and child welfare were obtained from HHS, Administration for Children and Families. Data on Medicaid, the State Children’s Health Insurance Program (SCHIP), and Medicare were obtained from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Poverty and population data were obtained from the U.S. Bureau of the Census. Gross domestic product (GDP) data were obtained from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. An expanded version of this exhibit is available as Expanded Exhibit 3, content.healthaffairs.org/cgi/content/full/23/5/131/DC1, along with an online appendix containing full bibliographic information.

NOTES: Spending is reported in 2000 constant dollars. Numbers may not add exactly to reported total and subtotals because of rounding. OASDI is Old Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance.

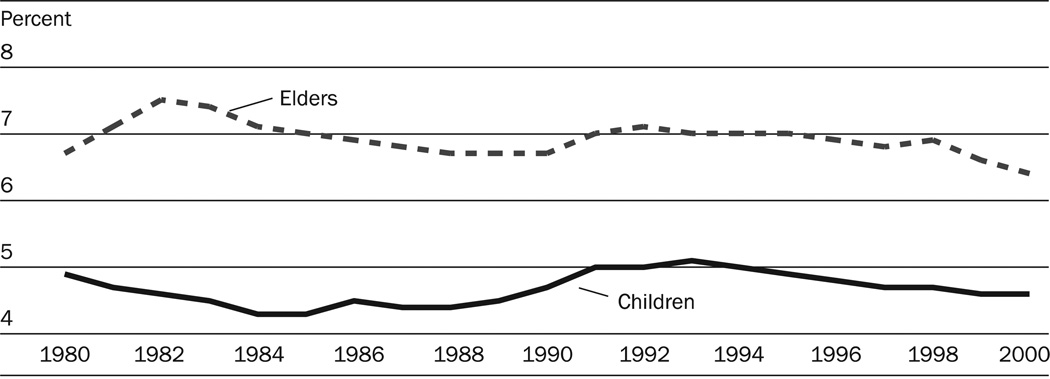

“Real” spending and as percentage of GDP

Social welfare spending in constant dollars (adjusted for inflation) for both children and the elderly grew over the study period. For children, real spending (in 2000 dollars) grew from $281 billion in 1980 to $459 billion in 2000. For the elderly, real spending grew from $380 billion in 1980 to $649 billion in 2000. However, as a percentage of GDP, social welfare spending for both groups was relatively unchanged (Exhibit 4).

EXHIBIT 4.

Social Welfare Spending On Children And Elders, As Percentage Of GDP, 1980–2000

SOURCE: Authors’ analysis of data on a variety of social welfare components. See Exhibit 3 sources and an online appendix, content.healthaffairs.org/cgi/content/full/23/5/131/DC1, for full bibliographic details.

NOTE: GDP is gross domestic product.

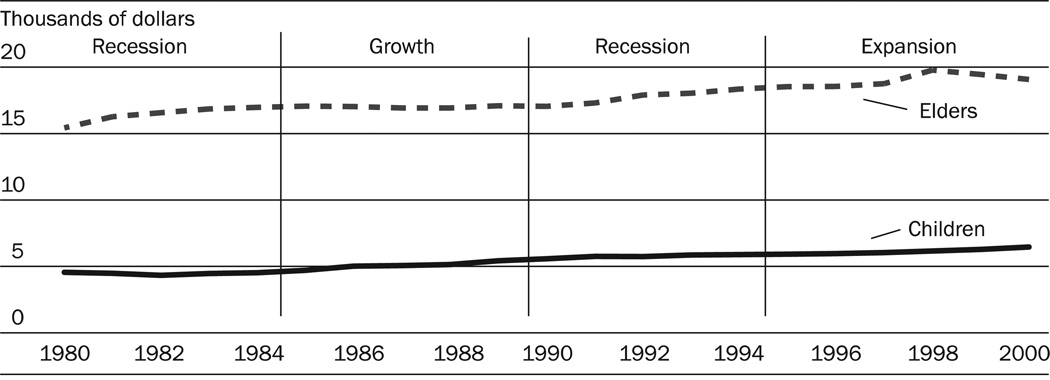

Per capita spending

We next examined trends in per capita social welfare spending to account for differences in population growth. Per capita social welfare spending grew from $4,464 per child in 1980 to $6,380 per child in 2000 (Exhibit 5). Per capita spending for the elderly grew from $15,404 in 1980 to $19,702 in 2000. The gap in per capita spending between the two groups grew nearly 20 percent—from about an $11,000 difference in 1980 to a more than $13,000 difference in 2000.

EXHIBIT 5.

Per Capita Social Welfare Spending On Children And Elders, 1980–2000

SOURCE: Authors’ analysis of data on a variety of social welfare components. See Exhibit 3 sources and an online appendix content.healthaffairs.org/cgi/content/full/23/5/131/DC1, for full bibliographic details.

NOTE: Changes in per capita spending for each time interval are presented in 2000 constant dollars. Changes in per capita spending were calculated as A–B. where A is per capita spending in year 2 and B is per capita spending in year 1.

Differences in per capita spending between children and the elderly grew during the recessions of the early 1980s and the early 1990s. As previously demonstrated by Benjamin and colleagues, spending on children’s programs suffered the most in 1980–1982 during the recession, when there was a 5.2 percent decrease in real total per capita total social welfare spending.19 In the ensuing period of growth, per capita public spending trends converged because of increased growth in spending on children. Real total per capita social welfare spending grew 15.8 percent for children and only 0.2 percent for elders. Despite this overall growth in per capita spending for children, most areas of social welfare spending on children declined in real dollars.

Increases in spending on children through Medicaid and food stamps made up for declines in other areas. In the recession of the early 1990s, differences between per capita public spending on children and the elderly increased as growth of spending on children failed to keep pace with that for the elderly. During this recession, real total per capita total social welfare spending on children grew 6.0 percent; on elders, 7.7 percent.

During the recent economic expansions of the late 1990s, total per capita social welfare spending rose 9.4 percent for children and 2.9 percent for the elderly. However, spending on children through AFDC and TANF dropped precipitously after passage of the 1996 PRWORA. At the same time, although medical spending on the elderly kept pace with inflation, medical spending on children fluctuated. From 1995 to 1997 it declined 22.5 percent and then increased 13.7 percent from 1998 to 2000 as Medicaid expansions and SCHIP were implemented.

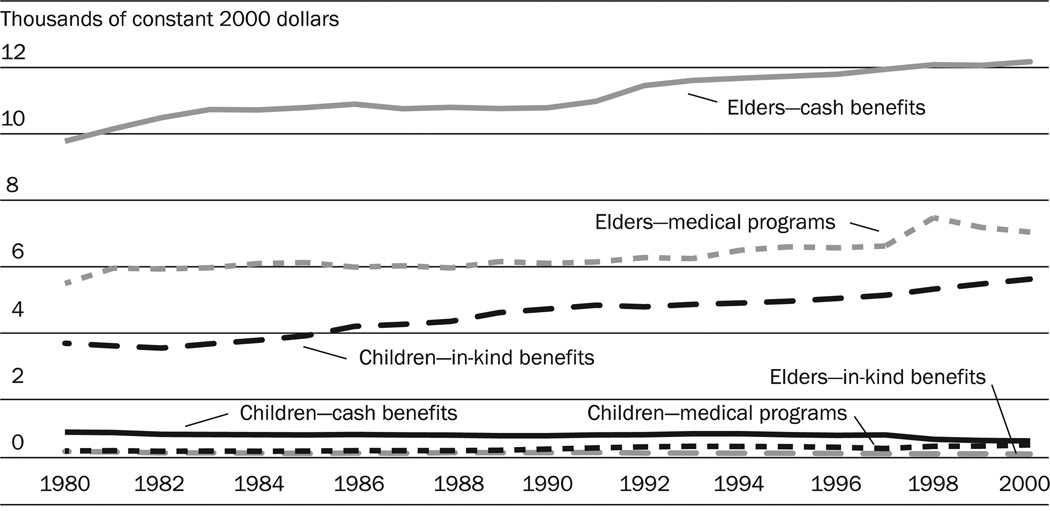

Explaining the gap

We found that differences in the growth rates of medical spending accounted for the majority of the widening gap during the study period. Per capita medical spending on children remained relatively flat, while per capita medical spending on elders grew (Exhibit 6). In contrast, the dominant mode of social welfare spending on children, per capita in-kind benefits (such as education and food assistance), kept pace with per capita spending on cash benefits (for example, Social Security and pensions) for the elderly, the predominant mode of spending on this group.

EXHIBIT 6.

Trends In Per Capita Spending On Children And Elders, 1980–2000

SOURCE: Authors’ analysis of data on a variety of social welfare components. See Exhibit 3 sources and an online appendix content.healthaffairs.org/cgi/content/full/23/5/131/DC1, for full bibliographic details.

NOTE: Cash benefits include Special Security, Supplemental Security Income, railroad retirement, veterans’ pensions, and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF)/Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) and emergency assistance. In-kind benefits include education, food assistance, Older Americans Act, child welfare, and maternal and child health programs. Medical programs include Medicare, Medicaid, and the State Children–s Health Program.

Discussion

Public policy and economic trends

Changes in public policy enacted in response to national economic trends have had great influence on the allocation of public spending.20 Spending on children’s programs suffered the most between 1980 and 1982 during the recession, when there was a 5.2 percent decrease in real per capita spending. To some extent, this large reduction was attributed to an unprecedented increase in the size of the population under age eighteen (which had been steadily decreasing since 1967). Substantial cuts in income-tested programs for children were authorized by the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (OBRA) and the Economic Recovery Tax Act of 1981.21 The result was that Medicaid and AFDC spending for children declined 10.7 percent and 7.2 percent, respectively, during this recession. Because of changes in eligibility criteria, Social Security payments to surviving children decreased even more steeply, by 19.3 percent.

The Family Support Act (FSA) of 1988 took effect just as the economic growth of the mid-1980s ended, largely in response to growing public dissatisfaction with increases in welfare case loads.22 The FSA reflected bipartisan consensus in which liberals achieved a broader safety net and conservatives achieved stronger work requirements for welfare recipients. Our analysis shows that social welfare spending on poor children through AFDC peaked in 1993 and then steadily declined in large part because of implementation of the FSA. The FSA served as a precursor to the dramatic shift in social policy that occurred with passage of the 1996 PRWORA. Although this legislation decoupled Medicaid and food-stamp eligibility from eligibility for cash assistance to preserve these benefits for needy families, multiple reports at the national, state, and local levels documented enrollment declines in all three programs.23 Our analysis confirms that declines in welfare case-loads were accompanied by declines in total public spending in TANF, Medicaid, and food stamps. Subsequent efforts to remedy inappropriate disenrollment from Medicaid, combined with the movement to Medicaid managed care, Medicaid privatization, and implementation of SCHIP, led to increased outreach efforts to enroll all eligible children in Medicaid.24 As a result, spending levels returned to their 1993 levels by 1999.

Devolution to the states

As the U.S. population ages and elderly people continue to have increasing and unmet medical needs, our observation that the growth of per capita medical spending on the elderly has exceeded the growth of per capita medical spending on children is not surprising. In an attempt to preserve health care benefits for elderly people in the future, the Balanced Budget Act (BBA) of 1997 included provisions to ensure the solvency of federally guaranteed Medicare trust funds.25 In contrast, current budgetary proposals continue to transfer funding responsibility and determination of eligibility requirements for social welfare programs, including Medicaid, from the federal government to the states, discounting the needs of 8.5 million uninsured U.S. children.26 This trend is particularly alarming in light of the fact that children represent an increasing proportion of the population living in poverty and that poverty has been persistently and repeatedly shown to be associated with poor health outcomes.27 Moreover, given that a large proportion of adult morbidities, such as cardiovascular disease and cancer, are associated with preventable childhood precursors, such as obesity and smoking, increasing and stabilizing investments in child health merit serious consideration.28

Study limitations

This study has several limitations. First, some programs providing benefits to both groups, such as public housing and the low-income home energy assistance program, do not provide data classified by age. These programs were not included in our analysis. Second, our analysis did not include indirect social welfare benefits for children and elders, such as those provided through tax subsidies. The Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), a refundable federal income tax credit for low-income working individuals and families, underwent modifications in 1993 and 1996 that led to large increases in the number of recipients and refunded amounts.29 Even though the total amount refunded grew from $1.3 billion in the 1980s to more than $26 billion in 2000, this would not offset the $190 billion gap in social welfare spending between children and the elderly in 2000.30 Furthermore, to avoid bias, consideration of tax policies designed to benefit children (such as refundable credits and nonrefundable deductions)warrants consideration of tax policies designed to benefit the elderly (such as tax-deferred retirement accounts and the Tax Credit for Elderly and Disabled).31 Estimating benefits to the elderly through the tax system would require complex statistical modeling that relied on untested assumptions about retirement account contributions, earnings, and distributions. Taking these issues into consideration, indirect social welfare benefits through the tax system were not included in our analysis. Further research in this area is needed. Despite these limitations, our findings provide evidence that unlike spending on elders, social welfare spending on children is vulnerable to downturns in the U.S. economy.

Persistent disparities in the proportion of children versus elders living in poverty and the importance of investments in preventive health argue for increased and stable social welfare spending on children’s programs. The continued transfer of responsibility for funding of social welfare programs from the federal government to the states endangers the stability of funding for all children’s social welfare programs, especially health insurance. Whereas the elderly are afforded a basic guarantee of support regardless of economic and political changes, social welfare spending on children is left vulnerable to these fluctuations. In the current period of economic stagnation, U.S. spending on children’s social welfare programs and health care is likely to be further compromised.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Susmita Pati is supported in part by a grant from the Anne E. Dyson Foundation. Ron Keren and Evaline Alessandrini are supported by Career Development Awards no. K23HD043179 and no. K23 HD01320-01A1, respectively, from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The authors gratefully acknowledge Jennifer Loftus for her assistance with the preparation of this manuscript.

NOTES

- 1.Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996. 1996 Aug 22;:104–193. 110 Stat. 2105. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mann C. The Bush Administration’s Medicaid and State Children’s Health Insurance Program Proposal. Washington: Georgetown University Institute for Health Care Research and Policy; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson GA, et al. It’s the Prices, Stupid: Why the United States Is So Different from Other Countries. Health Affairs. 2003;22(no. 3):89–105. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.22.3.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Society at a Glance: OECD Social Indicators, Edition 2002. Paris: OECD; 2003. Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. [Google Scholar]; Kawachi I, Kennedy BP. Income Inequality and Health: Pathways and Mechanisms. Health Services Research. 1999;34(no. 1):215–227. Part 2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Kennedy BP, Kawachi I, Prothrow-Stith D. Income Distribution and Mortality: Cross Sectional Ecological Study of the Robin Hood Index in the United States. British Medical Journal. 1996;312(no. 7037):1004–1007. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7037.1004. (see erratum in British Medical Journal 312, no. 7040 [1996]: 1194) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Martin JP. Transforming Social Protection for the Twenty-first Century; Paper presented at Prime Finland 2020; 2004. Mar 29, [Google Scholar]

- 4.OECD. Society at a Glance [Google Scholar]

- 5.U.S. Bureau of the Census, Current Population Survey, Annual Social and Economic Supplements, Poverty and Health Statistics Branch/HHES Division. Table 3, Poverty Status of People by Age, Race, and Hispanic Origin: 1959 to 2002. Historical Poverty Tables. 2003 Oct 2; www.census.gov/hhes/poverty/histpov/hstpov3.html (21 June 2004).

- 6.Ibid. According to U.S. Census Bureau estimates, the number of Americans age sixty-five and older will grow from 41.4 million in 2001 (14 percent of the population) to 101.4 million in 2050 (25 percent of the population).

- 7.2004 Annual Report of the Boards of the Trustees of the Federal Hospital Insurance and Federal Supplementary Medical Insurance Trust Funds. Washington: Boards of Trustees; 2004. Boards of Trustees, Federal Hospital Insurance and Federal Supplementary Medical Insurance Trust Funds. [Google Scholar]

- 8.OECD. Society at a Glance [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benjamin AE, Newacheck PW, Wolfe H. Intergenerational Equity and Public Spending. Pediatrics. 1991;88(no. 1):75–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ibid.

- 11.For food stamps, elderly are considered to be those over age sixty, and children are considered to be those under age eighteen.

- 12.Gold MR, editor. Cost-Effectiveness in Health and Medicine. New York: Oxford University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 13.The study sample is the entire U.S. population, so statistical inferences and testing are not necessary to evaluate the significance of observed differences and trends.

- 14.Full bibliographic information is available in an online appendix, content.healthaffairs.org/cgi/content/full/23/5/131/DC1.

- 15.Elderly people’s portion of Social Security includes payments to retired workers, their wives and husbands, surviving widowed mothers and fathers, widows and widowers, parents, and special beneficiaries. The children’s portion includes payments to retired workers’ children and surviving children.

- 16.Appropriations under the Older Americans Act were tracked by the House Committee on Aging in the mid- to late 1980s in a series of volumes entitled Developments in Aging.

- 17.Child nutrition programs include National School Lunch, School Breakfast, and Special Milk Programs.

- 18.Because of space limitations, spending data are presented for selected years 1980–2000. An expanded Exhibit 3 is available at content.healthaffairs.org/cgi/content/full/23/5/131/DC1.

- 19.Benjamin, et al. Intergenerational Equity and Public Spending. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Steuerle CE. The Incredible Shrinking Budget for Working Families and Children. Washington: Urban Institute; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 21.U.S. House Committee on Ways and Means. Green Book, 1994: Background Material and Data on Programs within the Jurisdiction of the Committee on Ways and Means. 14th ed. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office; 1994. Mar, [Google Scholar]

- 22.Family Support Act of 1988. 1988 Oct 13;:100–485. [Google Scholar]

- 23.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Change in TANF Caseloads since Enactment of New Welfare Laws. Washington: HHS, Administration for Children and Families; 2000. [Google Scholar]; U.S. Department of Agriculture. The Decline in Food Stamp Participation: A Report to Congress. Washington: USDA; 2001. [Google Scholar]; U.S. Government Accountability Office. Medicaid Enrollment: Amid Declines, State Efforts to Ensure Coverage after Welfare Reform Vary. Washington: GAO; 1999. [Google Scholar]; Kronebusch K. Children’s Medicaid Enrollment: The Impacts of Mandates, Welfare Reform, and Policy Delinking. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law. 2001;26(no. 6):1223–1260. doi: 10.1215/03616878-26-6-1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Pati S, Romero D, Chavkin W. Changes in Use of Health Insurance and Food Assistance Programs in Medically Underserved Communities in the Era of Welfare Reform: An Urban Study. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92(no. 9):1441–1445. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.9.1441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Zedlewski SR. Leaving Welfare Often Severs Families’ Connections to the Food Stamp Program. Journal of the American Medical Women’s Association. 2002;57(no. 1):23–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cunningham PJ, Reschovsky JD, Hadley J. Issue Brief no. 59. Washington: Center for Studying Health System Change; 2002. SCHIP, Medicaid Expansions Lead to Shifts in Children’s Coverage; pp. 1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Racine AD, et al. Differential Impact of Recent Medicaid Expansions by Race and Ethnicity. Pediatrics. 2001;108(no. 5):1135–1142. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.5.1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Balanced Budget Act of 1997. 1997 Aug 5;:105–133. [Google Scholar]

- 26.U.S. Census Bureau. Table 1—People without Health Insurance for the Entire Year by Selected Characteristics: 2001 and 2002. 2003 Sep 30; www.census.gov/hhes/hlthins/hlthin02/hi02t1.pdf (21 June 2004).

- 27.Aday LA, et al. Health Insurance and Utilization of Medical Care for Children with Special Health Care Needs. Medical Care. 1993;31(no. 11):1013–1026. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199311000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Byck GR. A Comparison of the Socioeconomic and Health Status Characteristics of Uninsured, State Children’s Health Insurance Program–Eligible Children in the United States with Those of Other Groups of Insured Children: Implications for Policy. Pediatrics. 2000;106(no. 1):14–21. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.1.14. Part 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Fiscella K, Franks P. Poverty or Income Inequality as Predictor of Mortality: Longitudinal Cohort Study. British Medical Journal. 1997;314(no. 7096):1724–1727. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7096.1724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Marmot M. The Influence of Income on Health: Views of an Epidemiologist. Health Affairs. 2002;21(no. 2):31–46. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.2.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Newacheck PW. Poverty and Childhood Chronic Illness. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine. 1994;148(no. 11):1143–1149. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1994.02170110029005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.HHS. Healthy People 2010: Understanding and Improving Health. 2d ed. Washington: U.S. GPO; 2000. Nov, [Google Scholar]

- 29.See Note 18. According to the Internal Revenue Service, more than 98 percent of EITC refunds in 1999 went to families. IRS. Compliance Estimates for Earned Income Tax Credit Claimed on 1999 Returns. Washington: Department of the Treasury, IRS; 2002. Feb 28, Green Book, 2004. 18th ed. Washington: GPO; 2004. Mar, Detailed legislative history is available from House Committee on Ways and Means.

- 30.House Committee on Ways and Means. Green Book. 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ibid.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.