Abstract

NO, a free radical gas, is the signal for Nitrosomonas europaea cells to switch between different growth modes. At an NO concentration of more than 30 ppm, biofilm formation by N. europaea was induced. NO concentrations below 5 ppm led to a reversal of the biofilm formation, and the numbers of motile and planktonic (motile-planktonic) cells increased. In a proteomics approach, the proteins expressed by N. europaea were identified. Comparison studies of the protein patterns of motile-planktonic and attached (biofilm) cells revealed several clear differences. Eleven proteins were found to be up or down regulated. Concentrations of other compounds such as ammonium, nitrite, and oxygen as well as different temperatures and pH values had no significant effect on the growth mode of and the proteins expressed by N. europaea.

Ammonia oxidizers like Nitrosomonas europaea are a versatile group of microorganisms that are present in many ecosystems (8, 35, 46). Ammonia oxidation is the preferred option for these organisms to gain energy (1, 3, 7, 15, 31), but they are also able to grow under oxic or anoxic conditions with hydrogen and/or organic compounds such as organic acids, sugars, and amino acids as electron donors and nitrite as the electron acceptor (8, 11, 12, 19, 24, 45). Ammonia oxidizers can also denitrify with ammonia as the electron donor under anoxic and oxygen-limited conditions by using N2O4 as an oxidant for ammonia oxidation (33). The nitrogen oxides, NO and NO2, are involved in the oxidation of ammonia, and they have regulatory effects on the metabolisms of the nitrifiers (34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 49). In Escherichia coli, the SoxR protein, a redox-sensitive transcription activator dependent on the oxidation state of its binuclear iron-sulfur ([2Fe-2S]) centers, is activated upon exposure to NO (14). This is a reaction of the cells against oxidative stress initiated by NO and superoxide radicals. Here, NO is neither produced nor is its concentration controlled to initiate the signal cascade. A further example of the role of NO has been described for the NO signaling and transcriptional control of denitrification genes in Rhodobacter (22, 23), Paracoccus (25), Pseudomonas (44, 50), and Ralstonia (26).

The Joint Genome Institute has completed the genome sequencing of N. europaea (http://www.jgi.doe.gov/tempweb/JGI_microbial/html/index.html). The genome sequence comprises 2.8 Mb and nearly 2,700 open reading frames (ORFs), half of which can be attributed to known functions (10). How many of these genes are expressed at a given time and the abundance of the expressed proteins cannot be predicted from the genome sequence. However, only few proteins of the ammonia oxidizers (N. europaea) have been purified and their activities examined (2, 3, 4, 20, 21, 32). The genome sequencing in combination with protein identification allows correlation of the genome with the proteome and the phenotype. This opens the possibility of analyzing NO signal transduction and regulation pathways and comparing the roles of NO signal transduction in ammonia oxidizers and other organisms (18). A successful method for obtaining information about the correlation between genome and phenotype is the analysis of proteomic data. Extended by post-source decay analysis, the peptides and proteins can be sequenced and identified based on hypothetical proteolytic fragments generated from the genome sequence ORF database for N. europaea (http://pedant.gsf.de/).

N. europaea is a motile microorganism that can form biofilms. Interestingly, the organization of the flagellar and flagellar biosynthesis genes and their operon localization in the genome are different from those in other bacteria (10), and the mechanism(s) of regulation of the growth mode is still unknown. Trémoulet et al. (42) studied the proteins expressed in biofilm and motile-planktonic cells of E. coli and described 17 proteins to be up or down regulated, indicating clear differences in the protein patterns dependent on the growth mode. The importance of motility for the bacterium-substratum contact, the process of attachment (outer membrane protein adhesion and extracellular polymeric substance production), and the biofilm structure of different bacteria has been studied in detail (29), but little is known about the primary signal(s) and a possible signaling cascade inducing the change between motile-planktonic and biofilm growth modes and the correlated changes in the protein patterns (17). Neither physical parameters such as shear forces or retention times in reactor systems nor limitation or excess of substrates has been proven to be the direct signal for the induction of biofilm formation.

An earlier study has shown that gaseous NOx (NO or NO2) induces the production of the ammonia monooxygenase by ammonia oxidizers that were previously grown under anoxic conditions with hydrogen as the electron donor and nitrite as the electron acceptor (38). In the present study, we provide evidence that NO is a signal molecule controlling the growth mode of N. europaea. We have examined how different growth conditions influence the growth mode of N. europaea (motile-planktonic or biofilm) and how the expression of 11 proteins (including six flagellum-related proteins) differs depending on the growth conditions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Organism.

Cultures of N. europaea (ATCC 19178), Nitrosomonas eutropha strain N904, Nitrosolobus multiformis (ATCC 25196), and Nitrosospira briensis (ATTC 25971) were grown aerobically in 1-liter Erlenmeyer flasks containing 400 ml of mineral medium (33). The cultures were grown for 1 to 2 weeks in the dark at 28°C without stirring or shaking.

Experimental design (chemostat).

N. europaea was grown in 5-liter laboratory-scale reactors with 3.5 liters of medium (Adaptive Biosystems Ltd., Luton, United Kingdom). The reactors were aerated (0.1 to 2 liters min−1) with variable mixtures of air, argon, and NO (0 to 250 ppm) by using mass-flow controllers (Adaptive Biosystems Ltd.). NO and NO2 concentrations in the fresh gas (inlet) and off-gas (outlet) were constantly monitored, and medium level, temperature, dissolved oxygen concentration, and pH value were measured and controlled. Temperature was maintained at 28°C, and dissolved oxygen was maintained at a concentration of 0.04 to 6 mg liter−1. The pH value was kept at 7.4 by means of a 20% Na2CO3 solution. Samples for the off-line determination of ammonium, nitrite, nitrate, and N2O concentrations and cell numbers were taken within regular time intervals. The dilution rate varied between 0.002 (start-up) and 0.1 h−1. The medium contained 150 to 3,000 mg of NH4+-N per liter (10 to 200 mM NH4+). The effluent was collected and stored at 4°C. The reactors were inoculated with 400 ml of an N. europaea culture. Control experiments were carried out with N. eutropha, Nitrosolobus multiformis, Nitrosospira briensis, cell-free medium, and heat-sterilized cell suspensions. The growth mode was classified as motile cells (motile single cells), planktonic cells (nonmotile single cells), and biofilm cells (nonmotile cells in biofilms). The term motile-planktonic cells describes all single, nonattached cells (motile plus nonmotile).

Analytical procedures.

Ammonium was measured according to the method of Schmidt and Bock (33), and nitrite and nitrate were measured according to the method of Van de Graaf et al. (43). NO and NO2 concentrations were measured online with an NOx analyzer (Eco Physics, Dürnten, Switzerland), the protein concentrations were determined according to the method of Bradford (9), and the numbers of motile and planktonic (nonmotile) Nitrosomonas cells were determined by light microscopy using a Helber chamber (standard deviation [SD], 5%). For the determination of the numbers of attached (biofilm) cells, biomass samples were taken from the glass walls of the reactors. The cells were resuspended (single cells to small aggregates), and the cell number was determined in the counting chamber. Parallel to that procedure, the ammonia oxidation activity of the resuspended biofilm cells was determined and used to calculate the cell number (107 cells oxidize 38 ± 3 nmol of NH4+ h−1). The average of values from both methods was calculated (SD, 14%). The surface area of the reactor system available for biofilm formation was taken into account to calculate the total cell number of ammonia oxidizers in the biofilm. This number was converted into cell number per milliliter to allow direct comparison between the numbers of motile-planktonic and biofilm cells.

Sample preparation.

Cells of Nitrosomonas grown in the 5-liter laboratory-scale reactors were harvested, washed twice, suspended in demineralized water, and homogenized by passing the suspension through a French pressure cell at 140 MPa. Intact cells were removed by a 5-min centrifugation at 8,000 × g. A small fraction of the supernatant was used to determine the protein concentration, while the rest was treated using a two-dimensional (2D) cleanup kit (PlusOne; Amersham Bioscience Corp., Little Chalfont, England). The protein was resuspended in sample buffer {7 M urea, 2 M thiourea, 4% (wt/vol) 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)-dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate (CHAPS), 60 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 2% (vol/vol) immobilized pH gradient (IPG) buffer (pharmalyte; Amershan Bioscience), and 0.002% (wt/vol) bromophenol blue}, incubated (30 min at room temperature), and centrifuged (5 min at 8,000 × g), and the supernatant was transferred for isoelectric focusing (IEF).

Electrophoresis.

All chemicals and apparatuses were supplied by Amersham Bioscience. For the IEF (Ettan IPGphor), the protein sample (100 μg of protein on IPG strips of pH 4 to 7 or 250 μg of protein on narrow-interval IPG strips) was loaded onto the strip holder (24 cm), and the IPG strips were positioned and covered with mineral oil. After IEF, the IPG strips were equilibrated first for 15 min in a buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), 8 M urea, 30% (vol/vol) glycerol, 1% (wt/vol) sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), and 1% (wt/vol) DTT and second for 15 min in the same buffer without DTT but with 2.5% (wt/vol) iodoacetamide and 0.002% (wt/vol) bromophenol blue. The equilibrated strips were then placed onto the 12 to 14% SDS gel (ExcelGel XL), and the proteins were separated in a 20-mA stacking period and a 40-mA separation period (Multiphor II) together with a broad-range molecular mass marker (10 to 250 kDa; Bio-Rad). Proteins were then fixed and stained on the gels by silver staining (30).

Image analysis and protein identification by peptide mass spectrometry.

The digitalization of 2D protein patterns was performed using a Sharp JX330 scanner interfaced with the ImageMaster 2D Elite software (Amersham Bioscience). The images were converted into a parameter list to determine the number of spots and their relative densities and to generate reference spot numbers for tracking protein identification.

Protein spots of interest were cut from the gel (by hand or by use of an Ettan spot picker), the gel slices were destained (solutions contained 200 mM ammonium bicarbonate in 50% acetonitrile) and dried, and the proteins were in-gel digested with Promega sequence grade trypsin at 20 μg ml−1. The peptides were eluted from the gel slices by extraction with 40 mM ammonium bicarbonate in 10% acetonitrile, desalted and concentrated with ZipTip pipette tips (Millipore, Bedford, Mass.), mixed with α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (10 mg ml−1) in 70% acetonitrile, and spotted onto a matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometer target plate. The plate was transported into a Biflex III MALDI-TOF mass spectrometer (Bruker Analytical Systems Inc., Billerica, Mass.). The peptides in the spotted sample were subjected to irradiation by a laser. The peptide ions generated by 120 to 250 laser shots were transmitted through an electric field onto a mass analyzer. The signals were accumulated, and a mass-to-charge (m/z) spectrum was generated. The proteins were identified using Bruker Xtof 5.1.0. and BioTool 2.0 software via peptide mass fingerprinting (Mascot 1.7.1) with calculated m/z values from the N. europaea ORF database (http://pedant.gsf.de/). The significance of the protein identification was evaluated by calculating the probability-based mowse scores as −10 multiplied by log(P), where P is the probability that the observed match is a random event. The mowse scores of the identified proteins ranged between 75 and 135 (mowse scores of greater than 45 are significant [P < 0.05]). Single peptides were further analyzed in the post-source decay mode of the MALDI-TOF mass spectrometer to obtain the amino acid sequences and to confirm the identification (40).

RESULTS

Effect of NO on N. europaea growth mode.

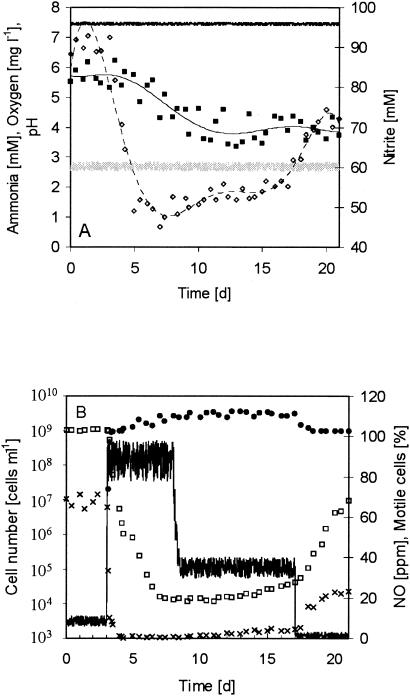

The initial experiments were designed to investigate the influence of nitric oxide on the growth mode—motile, planktonic (but immobile), or sessile (biofilm)—of N. europaea under defined growth conditions. For these experiments (three replicates), N. europaea was cultured in 5-liter laboratory-scale reactors for 3 weeks in the absence of NO (data not shown). The experiments were started when the cell number reached a steady state (109 cells ml−1; SD, 5%) (Fig. 1). Throughout the experiments, the temperature (28 ± 0.05°C), the oxygen concentration (2.6 ± 0.1 mg liter−1), and the pH value (7.4 ± 0.02) were kept constant. The reactor system was aerated with 0.2 liters of air min−1, the dilution rate was adjusted to 0.08 h−1, and the ammonium concentration in the medium was maintained at 100 mM (the medium contained no nitrite or nitrate). N. europaea converted the ammonia mainly into nitrite (a nitrite concentration of 91 ± 3 mM was detectable); nitrate was not formed (Fig. 1). The loss of about 7% of soluble nitrogen compounds resulted from the formation of nitric oxide, nitrous oxide, and dinitrogen (33, 37, 38). About 70% ± 7% of the planktonic cells were motile. Neither attachment of cells nor the formation of a biofilm was detectable in this period of time.

FIG. 1.

N. europaea was grown in motile-planktonic or biofilm mode for 3 weeks in a 5-liter laboratory-scale reactor. Aeration with gas supplemented with NO at a concentration of 200 ppm began on day 3, and NO supplementation was stopped on day 8. On day 17, the level of aeration increased from 0.2 to 2 liter min−1 to reduce (dilute) the NO concentration. (A) Ammonium (filled squares), oxygen (gray line), and nitrite (open diamonds) concentrations and pH values (black line). (B) NO concentration in the off-gas (black line), number of motile-planktonic cells (open squares) and biofilm cells (filled circles), and ratio of motile to motile-planktonic cells (x).

After 3 days, the reactor system was supplemented with a 200-ppm concentration of NO (adjusted in the gas inlet); the NO concentration in the off-gas stabilized at about 90 ppm (Fig. 1B). Two major effects of NO on N. europaea were detectable. First, the growth mode changed rapidly (Fig. 1B). Within 1 day, the cells lost their mobility, and the number of planktonic cells decreased from about 109 cells ml−1 to about 2 × 104 cells ml−1 after 4 days. Simultaneously, the number of attached cells increased to about 2 × 109 cells ml−1. Interestingly, only about 35% of the planktonic cells present at day 3 were removed from the reactor system with the effluent; hence, most of the cells (65%) attached to the substratum in the reactor. Second, the addition of NO induced higher denitrification activity of N. europaea as indicated by the decrease in nitrite concentration (Fig. 1A) and the increase in N loss from 7% to about 50%. The ammonia oxidation activity did not change significantly (638 mmol of NH4+ day−1 without NO and 650 mmol of NH4+ day−1 in the presence of NO).

In further experiments, the supplementation of NO was stopped at day 8 to examine whether the change in growth mode was reversible (Fig. 1B). Although NO was not added to the reactor system, its concentration in the off-gas remained high at 35 ppm, which corresponds to the production of about 450 μmol of NO day−1. Release of high concentrations of NO during ammonia oxidation has been described previously for N. eutropha (34, 48, 49). Approximately 0.7% of the consumed ammonia was converted to NO. Obviously, this NO concentration was sufficient to maintain the biofilm growth mode. For 9 days, the numbers of planktonic and motile cells remained low. The aeration was increased from 0.2 to 2 liter min−1 from day 17 onward to reduce the NO concentration (Fig. 1B), and argon was added to the aeration gas to keep the oxygen concentration constant. Another reactor system was supplied with 3 mmol of 2,3-dimercapto-1-propane-sulfonic acid (DMPS) per day. DMPS is an NO binding compound that can be used to reduce the NO concentration in Nitrosomonas cell suspensions (48). As a result, the NO concentrations in the reactor system decreased to 0.5 to 3 ppm. At these low NO concentrations, the growth mode of N. europaea changed again (Fig. 1B). The number of planktonic cells increased within 4 days to about 107 cells ml−1, of which 20% were motile. The number of attached cells did not change significantly. When the reactor systems were supplemented with NO2 (at concentrations of 100 to 150 ppm; data not shown), a substrate and activator of ammonia oxidation (36, 37, 38), detached biofilm fragments were detectable in the medium within 10 h. After 5 days, most of the biofilm was detached.

In further experiments, the effects of different compounds and growth conditions on the formation of biofilms were studied. The ammonium (0.2 to 85 mM), nitrite (0.1 to 120 mM), and oxygen (0.2 to 5 mg liter−1) concentrations as well as the pH values (6.8 to 7.8) and the temperatures (15 to 28°C) were modified without influencing the growth mode of N. europaea (Table 1). Likewise, variation of the shear forces (stirrer speeds between 150 and 800 rpm) and the retention times (0.05 to 0.5 h−1) did not induce biofilm formation within 12 volume changes of the reactor system (the oxygen concentration was kept constant at 3 mg liter−1). At a retention time above 0.2 h−1, the cells were washed out. A nitrite concentration of 120 mM and an oxygen concentration of 0.2 mg liter−1 resulted in high NO concentrations (Table 1), and subsequently low numbers of biofilm cells were detectable. When DMPS was added, the NO concentrations remained below 5 ppm and biofilm formation did not occur (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Effects of NO, ammonium, nitrite, and oxygen concentrations, pH value and temperature on the growth mode, ammonia oxidation activity, and N loss of N. europaeaa

| Modified growth condition | No.b of planktonic cells ml−1/ no. of biofilm cells ml−1 | Amt of ammonia oxidized (mmol day−1) | N loss (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| NO concn (ppm) in headspace | |||

| <1 | 3 × 109/<1 × 103 | 638 | 7 |

| 5 | 3 × 109/<1 × 103 | 642 | 11 |

| 50 | 2 × 104/3 × 109 | 650 | 50 |

| Ammonium concn (mM) in cell suspension | |||

| 0.2 | 2 × 107/<1 × 103 | 9 | 6 |

| 5 | 1 × 109/<1 × 103 | 635 | 7 |

| 85 | 9 × 108/<1 × 103 | 614 | 4 |

| Nitrite concn (mM) in cell suspension | |||

| 0.1 | 4 × 109/<1 × 103 | 627 | 9 |

| 20 | 4 × 109/<1 × 103 | 597 | 9 |

| 120 | 8 × 108/2 × 104c,e | 601 | 31 |

| Oxygen concn (mg liter−1) in cell suspension | |||

| 0.2 | 7 × 107/4 × 103d,e | 85 | 26 |

| 3 | 1 × 109/<1 × 103 | 627 | 9 |

| 5 | 3 × 109/<1 × 103 | 585 | 6 |

| pH value | |||

| 6.8 | 8 × 107/<1 × 103 | 137 | 8 |

| 7.3 | 4 × 109/<1 × 103 | 612 | 4 |

| 7.8 | 3 × 108/<1 × 103 | 595 | 10 |

| Temperature (°C) | |||

| 15 | 6 × 107/<1 × 103 | 58 | 9 |

| 22 | 6 × 108/<1 × 103 | 489 | 5 |

| 28 | 2 × 109/<1 × 103 | 624 | 5 |

The cell numbers ammonia oxidation activity, and N loss were determined 5 days after one value was changed (about 12 volume changes).

SD, 5%.

At a nitrite concentration of 120 mM, a NO concentration of about 35 ppm was detectable (chemodenitrification).

At an oxygen concentration of 0.2 mg liter−1, a NO concentration of about 43 ppm was detectable.

When the NO concentration was lowered (<5 ppm) by the addition of DMPS, biofilm cells were not detectable.

Parallel experiments with N. eutropha, Nitrosolobus multiformis, and Nitrosospira briensis were performed (Table 2). The growth conditions for the three species were similar to those used for N. europaea, but the NO concentrations inducing the biofilm formation were different. N. eutropha, Nitrosolobus multiformis, and Nitrosospira briensis switched into the biofilm growth mode at NO concentrations of about 50, 10, and 5 ppm, respectively.

TABLE 2.

Growth modes of N. eutropha, Nitrosolobus multiformis, and Nitrosospira briensis in the presence of different NO concentrationsa

| NO concn (ppm) | No. of cells ml−1 of:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

N. eutropha

|

Nitrosolobus multiformis

|

Nitrosospira briensis

|

||||

| p | b | p | b | p | b | |

| 0 | 1 × 109 | ND | 8 × 108 | ND | 3 × 108 | ND |

| 5 | 2 × 109 | ND | 2 × 108 | ND | 9 × 104 | 3 × 107 |

| 10 | 1 × 109 | ND | 9 × 104 | 9 × 107 | 7 × 104 | 2 × 108 |

| 25 | 4 × 109 | ND | 5 × 104 | 5 × 107 | 8 × 104 | 1 × 108 |

| 50 | 9 × 104 | 9 × 108 | 4 × 104 | 9 × 107 | 6 × 103 | 1 × 108 |

| 100 | 2 × 104 | 3 × 109 | 5 × 103 | 7 × 107 | 1 × 102 | 5 × 108 |

The ammonia oxidizers were grown for 3 weeks without NO to reach a steady state. The numbers of motile-planktonic and biofilm cells per milliliter were measured 5 days after the NO supplementation was started (about 12 volume changes). p, planktonic-motile cells; b, biofilm cells; ND, not detectable.

Differences in the protein patterns between planktonic and biofilm cells of N. europaea.

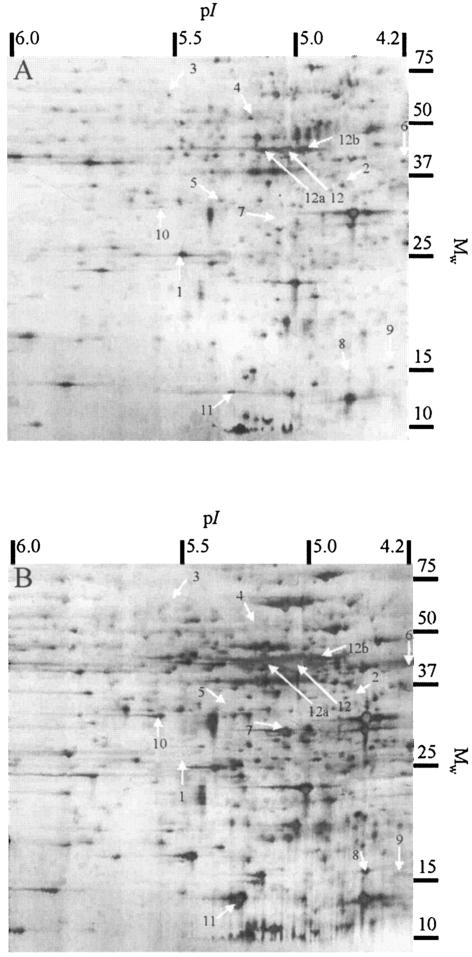

Samples of motile-planktonic cells (grown at NO concentrations below 10 ppm) were taken during days 1 to 3 and 13 to 21, and biofilm cells (grown at NO concentrations between 30 and 100 ppm) were harvested between days 5 and 21 (cf. Fig. 1). The protein patterns of motile-planktonic and biofilm cells revealed significant differences in the abundances of certain proteins. Eleven proteins were found to be significantly up or down regulated (Fig. 2). Six of the proteins could be identified as flagellar and flagellar assembly proteins, and three of these, FliH, FliG, and FliF (corresponding to code numbers gi 30250025, gi 30250024, and gi 30250023, respectively, in the ORF database), are encoded by genes located in one operon. The other five proteins belong to the energy metabolism (nitrosocyanin), carbon metabolism (succinyl coenzyme A [succinyl-CoA] synthetase alpha subunit), and regulation (transcription regulator and chemotaxis proteins) systems. The identified proteins shown in Table 3 were verified by analyzing replicate spots from six 2D gels. The appearance of proteins in multiple locations within the 2D pattern suggests posttranslational modification of these proteins (16). For example, one protein (Fig. 2), identified as porin (similar to porin of Bordetella pertussis), was found at multiple locations (pI 5.0, 5.1, and 5.2; spots 12, 12a, and 12b). In control experiments, ammonium (0.2 to 85 mM), nitrite (0.1 to 120 mM), and oxygen (0.2 to 5 mg liter−1) concentrations as well as the pH values (6.8 to 7.8) and the temperatures (15 to 28°C) were modified without influencing the protein pattern of N. europaea.

FIG. 2.

2D electrophoresis patterns of N. europaea proteins from cell extracts. The proteins were separated in the first dimension by IEF and in the second dimension by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. (A) Protein pattern of cells in the motile-planktonic growth mode. (B) Protein pattern of cells in the biofilm growth mode.

TABLE 3.

N. europaea proteins identified by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry showing different expression levels in biofilm and planktonic growth modes

| Protein ID no.a | Codeb | Mw | pI | Description and/or identity of protein or closest homologue | E valuec | Expressiond in:

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biofilm cells | Motile-planktonic cells | ||||||

| 1 | gi 30250025 | 26,729 | 5.5 | Flagellar assembly protein FliH | 3e − 17 | − | + |

| 2 | gi 30250024 | 36,689 | 4.9 | Flagellar motor switch FliG | 7e − 94 | − | + |

| 3 | gi 30250023 | 59,845 | 5.5 | Flagellar M-ring transmembrane protein FliF | 1e − 108 | − | + |

| 4 | gi 30249564 | 50,398 | 5.1 | Flagellar capping protein FliD | 9e − 44 | − | + |

| 5 | gi 30248480 | 37,314 | 5.3 | Flagellar motor switch FliM | 1e − 101 | − | + |

| 6 | gi 30248322 | 42,786 | 4.5 | Flagellar basal body rod protein | 1e − 85 | − | + |

| 7 | gi 30249875 | 26,881 | 5.1 | Response regulator OmpR consisting of a CheY-like receiver domain and a winged-helix DNA binding domain | 9e − 76 | + | − |

| 8 | gi 30249876 | 17,261 | 4.9 | Chemotaxis protein CheZ | 3e − 15 | + | − |

| 9 | gi 30249817 | 18,379 | 4.6 | Chemotaxis protein CheW | 1e − 46 | − | + |

| 10 | gi 30249769 | 30,879 | 5.6 | Succinyl-CoA synthetase alpha subunit | 6e − 98 | + | (+) |

| 11 | gi 30248169 | 14,522 | 5.4 | Red copper protein nitrosocyanin | —e | + | (+) |

| 12 | gi 30250482 | 42,876 | 5.1 | Porin | 2e − 06 | + | + |

| 12a | gi 30250482 | 42,876 | 5.2 | Porin | 2e − 06 | + | + |

| 12b | gi 30250482 | 42,876 | 5.0 | Porin | 2e − 06 | + | + |

ID, identification.

Code, code number for corresponding ORF in ORF database (http://pedant.gsf.de/).

E value, statistical score of the match in the E-value (frequentist) approach.

+, expressed; −, not expressed; (+), expressed at a low level.

Protein from N. europaea.

Genomic organization of genes encoding regulated proteins.

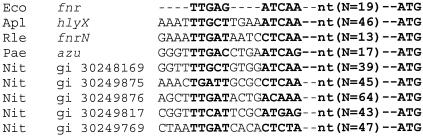

The localization and organization of the genes encoding flagellar and flagellar assembly proteins in the genome of N. europaea and other gram-negative bacteria such as E. coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Ralstonia solanacearum were found to be similar (data not shown), but the genes encoding chemotaxis proteins are in different positions. The three genes cheW, cheY, and cheZ are located at a short distance from one another in the genome of E. coli (in E. coli CFT073, between positions 2,117,221 and 2,122,792) and are flanked by genes encoding flagellar proteins and other chemotaxis proteins. In contrast, in the genome of N. europaea, cheW (positions 2,016,958 to 2,017,467) is located separately from cheZ and the cheY-like response regulator (positions 2,077,607 to 2,078,668) and these genes are flanked by genes encoding CbbR and RuBisCo proteins. Interestingly, the genes encoding the three chemotaxis proteins, the succinyl-CoA synthetase, and nitrosocyanin have a common fumarate-nitrate reduction (FNR) protein recognition sequence in the promoter region (Fig. 3). In contrast, the genes encoding flagellar and flagellar assembly proteins are not preceded by an FNR box. A homologue of the FNR protein of N. europaea was first identified in E. coli, where it plays a crucial role in the onset of expression of genes required for FNR (41). The promoter binding site of the FNR protein gene has the consensus sequence TTGAC-N4-ATCAA (where N is any nucleotide) (41). Corker and Poole (13) reported binding of NO at the FNR protein of E. coli by reaction with the [4Fe-4S] cluster of the protein, leading to inactivation of the FNR. The FNR protein has been described as a sensor for oxygen, but since changing oxygen concentrations did not induce a change in the growth mode (Table 1) or the protein pattern of N. europaea, NO may bind at the FNR protein, leading to the observed effects.

FIG. 3.

Compilation of potential binding sites for FNR protein homologues. Sequences were selected on the basis of their similarity to the core of the E. coli FNR protein binding site consensus. Eco, E. coli; Apl, Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae; Rle, Rhizobium leguminosarum; Pae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa; Nit, N. europaea. hlyX encodes hemolysin or protein that activates expression of the hemolysin gene, azu encodes a redox protein associated with denitrification, gi 30248169 encodes nitrosocyanin, gi 30249875 is a cheY homologue, gi 30249876 is a cheZ homologue, gi 30249817 is a cheW homologue, and gi 30249769 encodes succinyl-CoA synthetase alpha subunit (in one operon with gi 30249770, succinyl-CoA synthetase beta subunit). Boldface type indicates the FNR binding site consensus. nt, nucleotides; N, number of nucleotides.

DISCUSSION

In this report, the NO concentration was shown to influence the growth mode and the correlated protein pattern of N. europaea. Other compounds such as ammonium, nitrite, and oxygen as well as different pH values and temperatures were tested without having a significant influence on the growth mode (Table 1). Furthermore, the growth mode of N. europaea was not influenced by different stirring speeds (shear forces) or retention times, and the cells remained in the motile-planktonic growth mode. High nitrite (120 mM) and low oxygen (0.2 mg liter−1) concentrations led to increased NO concentrations and subsequently to the formation of a biofilm. NO was formed at high nitrite concentrations by chemodenitrification, and ammonia oxidizers produced NO at low oxygen concentrations by denitrification (27, 28, 48). Here, biofilm formation was not detectable when the NO binding compound DMPS was added to keep the NO concentration below 5 ppm.

In the presence of NO concentrations above 30 ppm, the number of motile-planktonic cells of N. europaea decreased while biofilm formation was detectable. Interestingly, the NO concentration stabilized at a high level (about 35 ppm) when the NO supplementation was stopped (Fig. 1B, day 8), and the cells remained in the biofilm growth mode. Obviously, the exposure of N. europaea to NO did not influence only the growth mode but also the metabolic activity, inducing increased NO production. Such increased denitrification activity and subsequently high NO production induced by NO treatment were already described for N. eutropha (37, 48). When NO was removed from the system, the cells reverted to the motile-planktonic growth mode and they expressed the typical protein pattern for motile-planktonic cells. Other ammonia oxidizers, N. eutropha, Nitrosolobus multiformis, and Nitrosospira briensis, also switched into the biofilm growth mode in the presence of NO; only the NO concentrations necessary were different. Hence, the induction of biofilm formation by NO is not restricted to N. europaea but seems to be common for ammonia oxidizers in general.

In the protein patterns of motile-planktonic and biofilm cells, several differences were detectable. Eleven proteins were identified that were significantly up or down regulated dependent on the growth mode. Six flagellar and flagellar assembly proteins were expressed in the motile-planktonic cells but were not detectable in immotile biofilm cells. Increasing the NO concentration induced the change in the growth mode, and the expression of flagellar protein was down regulated. The reverse process occurred when the NO supplementation was stopped and the NO concentration was adjusted to below 5 ppm; flagellar protein was expressed, and the number of motile-planktonic cells increased. Typical for the biofilm cells was the expression of the two regulatory proteins that are closest homologues to CheY and CheZ, while in motile-planktonic cells, a CheW homologue was detectable. The genes cheW, cheY, and cheZ are not only differently expressed dependent on the growth mode but their positioning and flanking genes differ in N. europaea and E. coli (10). In N. europaea, the genes cheY and cheZ are located about 60,000 nucleotides upstream of cheW, and they are not flanked by flh and other che genes (as in E. coli and other gram-negative bacteria) but, e.g., by cbb genes (genes of the Calvin-Benson-Bassham cycle). At this point, the importance of the different locations of the che genes in combination with their fluctuating expression intensities dependent on the growth mode is still unclear. Further research with, for example, che-deficient mutants (by integration of a suicide vector) (6) may elucidate the function of che genes in N. europaea. Interestingly, an FNR protein homologue is encoded in the genome of N. europaea. FNR proteins are transcription regulators, regulating the shift from aerobic to anaerobic growth in many bacteria. FNR protein dimerizes at low oxygen concentrations and binds to specific sites in promoters of its target genes upstream of and adjacent to the site where the RNA polymerase binds (41). In the promoter region of the genes for the chemotaxis proteins (CheW, CheY, and CheZ), the succinyl-CoA synthetase, and nitrosocyanin (nonflagellar proteins), FNR boxes were identified (Fig. 3). The presence of an FNR box suggests that the expression of these proteins is regulated via the FNR protein. In the promoter region of the genes encoding the flagellar and flagellar assembly proteins, an FNR box is missing.

The expression of the proteins nitrosocyanin and succinyl-CoA synthetase was modulated. Both proteins were detectable in motile-planktonic and biofilm cells, but their concentrations were significantly higher in biofilm cells (by approximately a factor of 10). Proteins such as plastocyanin, azurin, pseudoazurin, and rusticyanin, which are homologous to nitrosocyanin, mediate electron transfer (5, 47). Arciero et al. (5) suggested a similar function for nitrosocyanin. Possible electron donors include hydroxylamine oxidoreductase, cytochrome c554, cytochrome c552, and cytochrome cm552. Possible electron acceptors are cytochrome c552, cytochrome c554, ammonia monooxygenase, nitrite reductase, nitric oxide reductase, and cytochrome oxidase. This study gave evidence that N. europaea expressed nitrosocyanin in the biofilm growth mode at a higher level than did the motile-planktonic cells. Simultaneously, the NO production increased from 110 to 450 μmol of NO day−1 and the denitrification activity increased about sevenfold (N loss from 7 to 50%). This may indicate a function of nitrosocyanin in the denitrification and NO production of N. europaea. The succinyl-CoA synthetase catalyzes the reversible conversion of succinyl-CoA to succinate (citric-acid cycle). Although the citric-acid cycle is central to the energy-yielding metabolism in many microorganisms, the four- and five-carbon intermediates serve as biosynthetic precursors for a variety of products. Still, it is unclear why the succinyl-CoA synthetase concentration is higher in biofilm cells.

In this study, it has been shown that the NO concentration influences the growth mode (motile-planktonic or biofilm) of the tested ammonia oxidizers. The NO molecules may directly (e.g., by interacting with proteins or modulating their metabolic activities) or indirectly (by using not-yet-identified compounds or signal molecules) influence the growth mode and the metabolic activity of N. europaea (37, 38, 48, 49).

Acknowledgments

We thank Hubertus J. E. Beaumont for providing stock cultures of N. europaea (ATCC 19178).

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson, K. K., and A. B. Hooper. 1983. O2 and H2O are each the source of one O in NO2− produced from NH3 by Nitrosomonas; 15N-NMR evidence. FEBS Lett. 164:236-240. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson, K. K., T. A. Kent, J. D. Lipscomb, A. B. Hooper, and E. Münck. 1984. Mössbauer, EPR, and optical studies of the P-460 center of hydroxylamine oxidoreductase from Nitrosomonas. J. Biol. Chem. 259:6833-6840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arciero, D. M., and A. B. Hooper. 1993. Hydroxylamine oxidoreductase from Nitrosomonas europaea is a multimer of an octa-heme subunit. J. Biol. Chem. 268:14645-14654. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arciero, D. M., and A. B. Hooper. 1994. A di-heme cytochrome c peroxidase from Nitrosomonas europaea catalytically active in both the oxidized and half-reduced state. J. Biol. Chem. 269:11878-11886. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arciero, D. M., B. S. Pierce, M. P. Hendrich, and A. B. Hooper. 2002. Nitrosocyanin, a red cupredoxin-like protein from Nitrosomonas europaea. Biochemistry 41:1703-1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beaumont, H. J. E., N. G. Hommes, L. A. Sayavedra-Soto, D. J. Arp, D. M. Arciero, A. B. Hooper, H. V. Westerhoff, and R. J. M. van Spanning. 2002. Nitrite reductase of Nitrosomonas europaea is not essential for production of gaseous nitrogen oxides and confers tolerance to nitrite. J. Bacteriol. 184:2557-2560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bergmann, D. J., D. A. Arciero, and A. B. Hooper. 1994. Organization of the hao gene cluster of Nitrosomonas europaea: genes for two tetraheme c cytochromes. J. Bacteriol. 176:3148-3153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bock, E., I. Schmidt, R. Stüven, and D. Zart. 1995. Nitrogen loss caused by denitrifying Nitrosomonas cells using ammonium or hydrogen as electron donors and nitrite as electron acceptor. Arch. Microbiol. 163:16-20. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bradford, M. M. 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72:248-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chain, P., J. Lamerdin, F. Larimer, W. Regala, V. Lao, M. Land, L. Hauser, A. Hooper, M. Klotz, J. Norton, L. Sayavedra-Soto, D. Arciero, N. Hommes, M. Whittaker, and D. Arp. 2003. Complete genome sequence of the ammonia-oxidizing bacterium and obligate chemolithoautotroph Nitrosomonas europaea. J. Bacteriol. 185:2759-2773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clark, C., and E. L. Schmidt. 1966. Effect of mixed culture on Nitrosomonas europaea simulated by uptake and utilization of pyruvate. J. Bacteriol. 91:367-373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clark, C., and E. L. Schmidt. 1967. Growth response of Nitrosomonas europaea to amino acids. J. Bacteriol. 93:1302-1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Corker, H., and R. K. Poole. 2003. Nitric oxide formation by Escherichia coli. Dependence on nitrite reductase, the NO-sensing regulator Fnr, and flavohemoglobin Hmp. J. Biol. Chem. 278:31584-31592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ding, H., and B. Demple. 2000. Direct nitric oxide signal transduction via nitrosylation of iron-sulfur centers in the SoxR transcription activator. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:5146-5150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dua, R. D., B. Bhandari, and D. J. D. Nicholas. 1979. Stable isotope studies on the oxidation of ammonia to hydroxylamine by Nitrosomonas europaea. FEBS Lett. 106:401-404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Graves, P. R., and T. A. J. Haystead. 2002. Molecular biologist's guide to proteomics. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 66:39-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hall-Stoodley, L., and P. Stoodley. 2002. Developmental redulation of microbial biofilms. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 12:228-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hanafy, K. A., J. S. Krumenacker, and F. Murad. 2001. NO, nitrotyrosine, and cyclic GMP in signal transduction. Med. Sci. Monit. 7:801-819. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hommes, N. G., L. A. Sayavedra-Soto, and D. J. Arp. 2003. Chemolithoorganotrophic growth of Nitrosomonas europaea on fructose. J. Bacteriol. 185:6809-6814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hyman, M. R., and D. J. Arp. 1993. An electrophoretic study of the thermal-dependent and reductant-dependent aggregation of the 28 kDa component of ammonia monooxygenase from Nitrosomonas europaea. Electrophoresis 14:619-627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hyman, M. R., and P. M. Wood. 1985. Suicidal inactivation and labelling of ammonia monooxygenase by acetylene. Biochem. J. 227:719-725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kwiatkowski, A. V., W. P. Laratta, A. Toffanin, and J. P. Shapleigh. 1997. Analysis of the role of the nnrR gene product in the response of Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1 to exogenous nitric oxide. J. Bacteriol. 179:5618-5620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Laratta, W. P., and J. P. Shapleigh. 2003. Site-directed mutagenesis of NnrR: a transcriptional regulator of nitrite and nitric oxide reductase in Rhodobacter sphaeroides. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 229:173-178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martiny, H., and H.-P. Koops. 1982. Incorporation of organic compounds into cell protein by lithotrophic, ammonia-oxidizing bacteria. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 48:327-336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mazoch, J., M. Kunak, I. Kucera, and R. J. Van Spanning. 2003. Fine-tuned regulation by oxygen and nitric oxide of the activity of a semi-synthetic FNR-dependent promoter and expression of denitrification enzymes in Paracoccus denitrificans. Microbiology 149:3405-3412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pohlmann, A., R. Cramm, K. Schmelz, and B. Friedrich. 2000. A novel NO-responding regulator controls the reduction of nitric oxide in Ralstonia eutropha. Mol. Microbiol. 38:626-638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Poth, M. 1986. Dinitrogen production from nitrite by a Nitrosomonas isolate. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 52:957-959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Poth, M., and D. D. Focht. 1985. 15N kinetic analysis of N2O production by Nitrosomonas europaea: an examination of nitrifier denitrification. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 49:1134-1141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pratt, L. A., and R. Kolter. 1999. Genetic analyses of bacterial biofilm formation. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2:598-603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rabilloud, T. 1999. Silver staining of 2-D electrophoresis gels. Methods Mol. Biol. 112:297-305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rees, M., and A. Nason. 1966. Incorporation of atmospheric oxygen into nitrite formed during ammonia oxidation by Nitrosomonas europaea. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 113:398-401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sayavedra-Soto, L. A., N. G. Hommes, and D. J. Arp. 1994. Characterization of the gene encoding hydroxylamine oxidoreductase in Nitrosomonas europaea. J. Bacteriol. 176:504-510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schmidt, I., and E. Bock. 1997. Anaerobic ammonia oxidation with nitrogen dioxide by Nitrosomonas eutropha. Arch. Microbiol. 167:106-111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schmidt, I., and E. Bock. 1998. Anaerobic ammonia oxidation by cell-free extracts of Nitrosomonas eutropha. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 73:271-278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schmidt, I., E. Bock, and M. S. M. Jetten. 2001. Ammonia oxidation by Nitrosomonas eutropha with NO2 as oxidant is not inhibited by acetylene. Microbiology 147:2247-2253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schmidt, I., C. Hermelink, K. van de Pas-Schoonen, M. Strous, H. J. M. op den Camp, J. G. Kuenen, and M. S. M. Jetten. 2002. Anaerobic ammonia oxidation in the presence of nitrogen oxides (NOx) by two different lithotrophs. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:5351-5357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schmidt, I., D. Zart, and E. Bock. 2001. Gaseous NO2 as a regulator for ammonia oxidation of Nitrosomonas eutropha. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 79:311-318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schmidt, I., D. Zart, and E. Bock. 2001. Effects of gaseous NO2 on cells of Nitrosomonas eutropha previously incapable of using ammonia as an energy source. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 79:39-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Skiba, U., K. A. Smith, and D. Fowler. 1993. Nitrification and denitrification as sources of nitric oxide and nitrous oxide in a sandy loam soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 25:1527-1536. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Spengler, B., D. Kirsch, R. Kaufmann, and E. Jaeger. 1992. Peptide sequencing by matrix-assisted laser-desorption mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 6:105-108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Spiro, S. 1994. The FNR family of transcriptional regulators. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 66:23-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Trémoulet, F., O. Duché, A. Namane, B. Matinie, and J.-C. Labadie. 2002. A proteomic study of Escherichia coli O157:H7 NCTC 12900 cultivated in biofilm or in planktonic growth mode. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 215:7-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Van de Graaf, A. A., P. de Bruijn, L. A. Robertson, and J. G. Kuenen. 1996. Autotrophic growth of anaerobic ammonium-oxidizing micro-organisms in a fluidized bed reactor. Microbiology 142:2187-2196. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vollack, K. U., and W. G. Zumft. 2001. Nitric oxide signaling and transcriptional control of denitrification genes in Pseudomonas stutzeri. J. Bacteriol. 183:2516-2526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wallace, W., S. E. Knowles, and D. J. D. Nicholas. 1970. Intermediary metabolism of carbon compounds by nitrifying bacteria. Arch. Microbiol. 70:26-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Watson, S. W., E. Bock, H. Harms, H.-P. Koops, and A. B. Hooper. 1989. Genera of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria, p. 1822-1834. In J. T. Staley, M. P. Bryant, N. Pfennig, and J. G. Holt (ed.), Bergey's manual of systematic bacteriology. Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore, Md.

- 47.Whittaker, M., D. Bergmann, D. Arciero, and A. B. Hooper. 2000. Electron transfer during the oxidation of ammonia by the chemolithotrophic bacterium Nitrosomonas europaea. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1459:346-355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zart, D., and E. Bock. 1998. High rate of aerobic nitrification and denitrification by Nitrosomonas eutropha grown in a fermentor with complete biomass retention in the presence of gaseous NO2 or NO. Arch. Microbiol. 169:282-286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zart, D., I. Schmidt, and E. Bock. 2000. Significance of gaseous NO for ammonia oxidation by Nitrosomonas eutropha. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 77:49-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zumft, W. G. 2002. Nitric oxide signaling and NO dependent transcriptional control in bacterial denitrification by members of the FNR-CRP regulator family. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 4:277-286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]