Abstract

Objective

To explore the experiences of patients living with an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) who had received remote monitoring (RM).

Background

Anecdotal evidence suggests that not all patients with RM use the technology.

Methods

Focus groups of patients with an ICD who received an RM system. Transcripts reviewed using thematic analysis.

Results

Nine patients (3 women and 6 men; median [range] age, 73 [58–91] years) received an RM system. Patients were assigned to a group in regard to RM system use (nonusers, n=5; users, n=4). Few nonusers recalled having prior conversations about the system. Users described it as “simple” and “easy” to use. Nonusers often were unsure whether their system was correctly transmitting information. System benefits perceived by users included convenience and security. Nonusers expressed mistrust. Recommendations included early education and help lines.

Conclusions

Patient adherence to RM systems can be improved by explaining perceived benefits and addressing barriers to use.

Keywords: cardiovascular implantable electronic device, ethics, remote sensing technology

Introduction

An estimated 400,000 cardioverter-defibrillators are implanted in North America each year that have been traditionally managed through intermittent clinic visits (1). Nevertheless, in-clinic device checks may miss problems that develop between regularly scheduled visits. In some cases, remote monitoring (RM) systems have demonstrated a more than 90% success rate in identifying and transmitting device hardware problems, arrhythmias, and clinical deterioration within minutes, making this information readily available to health care professionals who manage the care of patients with an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) (2–8). Over time, use of RM systems to care for patients with an ICD has increased sharply; for many electrophysiology clinics, such usage has become the standard of care (8–11).

Use of data derived from RM systems in place of data derived from clinic visits has been shown to reduce the time and resources required to care for patients with an ICD (11–13). One study found that when RM was substituted for 2 in-clinic follow-up appointments, the overall cost of routine ICD follow-up was reduced by 41% per patient (14). Data from the Clinical Evaluation of Remote Notification to Reduce Time to Clinical Decision trial showed that RM reduced clinical decision response time and reduced the length of an associated hospital stay (15). Indeed, the savings in cost, time, personnel, and resources associated with use of RM systems can be substantial for a health care system (3,9,14,16,17).

The Lumos-T Safely Reduces Routine Office Device Follow-Up (TRUST) trial proved that RM could be efficacious and safe. The study found that patients who used RM had fewer clinical encounters (2.1 visits per patient per year) than patients who received care in clinic (3.8 visits per patient per year) (18). Furthermore, there was no increase in death, stroke, or surgical intervention among patients who used RM. Rather, RM was shown to promote adherence to device checks and prompt evaluation of cardiac episodes (12,18), including correctly identifying all clinical complications in study patients within 24 hours (19). Overall, 1- and 5-year survival rates of patients with an ICD and with a cardiac resynchronization therapy defibrillator who use RM systems were higher by 50% than patients who received follow-up care in clinic only (20).

Prior quantitative research suggests that patient satisfaction with RM is generally high. Specifically, nearly all patients surveyed (95%) believed that RM systems had a “positive effect” on their health and 98% reported being “completely satisfied” with RM (10). Nevertheless, in a comparison between patients who used RM and patients who received care in clinic, Al-Khatib and colleagues (21) found satisfaction to be higher among patients who received care in clinic but only for 6 months, whereafter there was no noticeable difference.

Little is known, however, about the perspectives of patients with an ICD regarding RM systems. In fact, evidence suggests that some patients with an ICD who have RM systems do not use them. Matlock (12) points out that a major deficiency of the TRUST trial is that it lacked data on the patient’s perspective, which is of “paramount importance” and “should be studied, not assumed.” Herein, we report the results of an original qualitative study that explored patients’ perspectives about their experiences with RM systems.

Methods

Design

Patients with an ICD who received RM systems were recruited from an academic medical center in the Midwestern United States. The subject sample was derived from patients who were registered as previously having received an RM system as part of their clinical care. Remote monitoring systems included all systems used at the academic medical center: Latitude (Boston Scientific Corp, Natick, Massachusetts), CareLink (Medtronic, Inc, Minneapolis, Minnesota), and Merlin (St. Jude Medical, Inc, St. Paul, Minnesota). Using a qualitative design (22), we sought to retrospectively understand why patients chose to use or not use an RM system.

Human Subjects

The population from which our sample was derived consisted of 133 residents of a single county in a Midwestern state. Transmission data indicated that 26 of these patients were not using their RM system at the time of recruitment. All 26 nonusers were invited to participate in the study. Of these, 5 patients consented and 4 actually participated. Twenty-six RM users were randomly identified and invited to participate. Of these, 7 patients consented and 5 actually participated. Overall, 9 patients participated.

Description of the Sample

Our sample was composed of patients from the same geographic area and cared for at the same institution. Selection of the sample size was based on accepted qualitative standards, which indicate the number of participants should be decided through a subjective determination by the researcher of how much data are required to assess the patient perspective and what can be accomplished with the resources available (23). Participants were assigned to 1 of 2 focus groups in accordance with their use of their RM system. Nonusers were defined as participants who had performed 2 or fewer transmissions with the system. Users were defined as participants who had performed 3 or more transmissions with their system.

Setting

The focus groups took place in June 2010 at an academic medical center in the Midwestern United States.

Data Collection

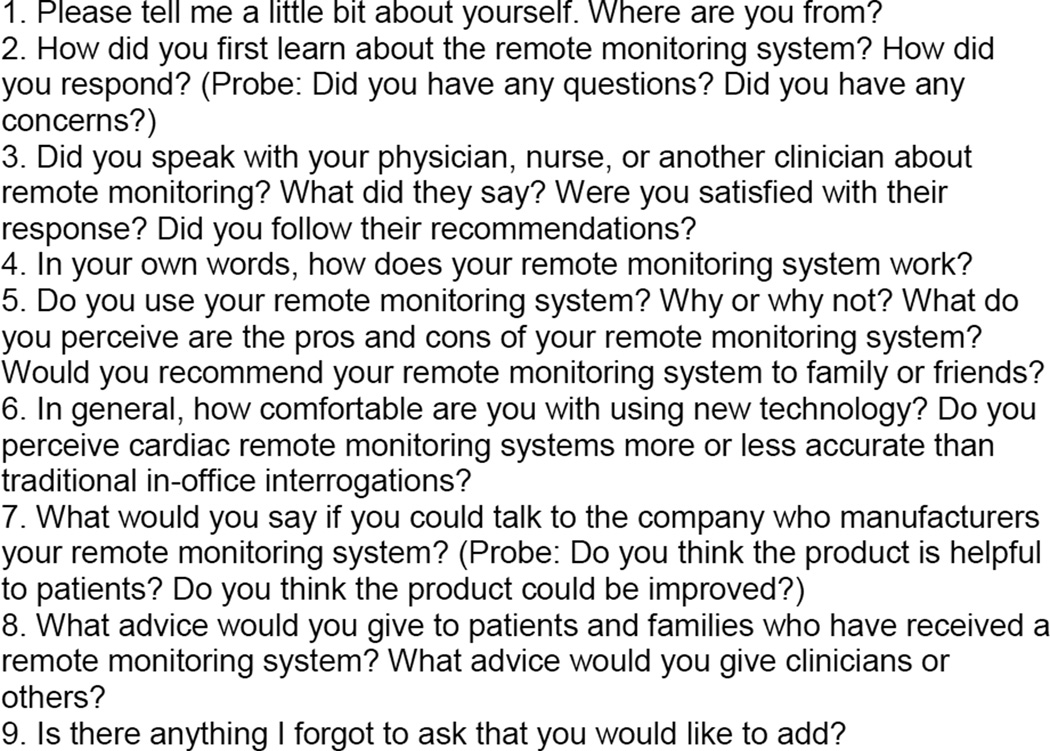

Each session lasted 90 minutes and was led by the same 2 trained focus group facilitators and 1 assistant facilitator, who took notes. The facilitators used an original semistructured interview guide (Figure) to stimulate discussion. Participants were encouraged to ask questions of each other and offer information about their perspectives or experience not probed with the interview guide. Focus group sessions were audio-recorded with permission from the participants. The transcripts were verified and deidentified by one of the assistant facilitators before analysis. Descriptive statistics were used to report demographic information.

Figure.

Interview Guide for Remote Monitoring Focus Group.

Analysis

Three members of the research team analyzed the transcripts by hand using open coding in accordance with standards of thematic analysis (23–26). To ensure rigor, all of the analysts completed the same baseline training on how to perform qualitative analysis. The analysts were instructed to independently read transcripts line by line and highlight sections of interest to formulate initial codes. A final codebook was arrived at through a series of meetings whereby each transcript was reviewed and codes were categorized. Disagreements were resolved by consensus. Five themes were applied to the transcripts, additional text was coded, and some portions were recoded. The study was conducted independent of any device manufacturer and approved by the institutional review board in accordance with federal regulations.

Results

A total of 9 patients (3 women and 6 men) participated in 2 focus groups (nonuser group, 4; user group, 5). The number of participants was sufficient to achieve data saturation or the point at which the data provided a description of the patient perspectives of each group (27). Patients who received the RM systems Latitude (4 participants), CareLink (3 participants), and Merlin (2 participants) were represented in both groups. The median age of participants was 73, with an age range of 58 to 91 years. The median time between implant and participation in the study was 2 years 8 months, with a range of 9 months to 11 years 2 months. The median distance of participants’ residence from the academic medical center was 6.1 miles, with a range of 0.8 to 13.2 miles. All participants self-identified as being white and married. A review of focus group transcripts uncovered several common themes associated with patient experiences and perspectives related to RM systems for ICDs (Box 1).

First Encounters

Users

Patients in the user group said that they received information about their RM systems in the clinic from their health care professional:

“ In the hospital, they told me everything before I went home. Before the discharge, they told me I would be getting the [remote] monitor [system]. They told me it would be mailed to me and if I had any problems setting it up to call, but it was very simple to set up. We had no problems, and I get a letter every 3 months from the clinic and they tell me [when] to transmit. The next day they call and tell me everything. So far everything has checked out.” (P3)

One patient mentioned being intimidated by the idea of using an RM system. After the purpose of the RM system was explained by a health care professional, the impressions of the patient and his spouse changed:

“ Well, at first when they mentioned [the remote monitoring system], I thought it sounded like something I didn’t think I wanted to get involved in because I thought maybe I wouldn’t know what I was doing. Well, then I found out how simple it was, so we went for it.” (Wife of P2)

All patients in the user group had conversations with their health care professionals before receiving their RM systems and knew which brand they had received.

Nonusers

Patients in the nonuser group reported receiving their RM systems unexpectedly. In fact, most did not know what the RM system was or what it was supposed to do:

“ We didn’t know how to put it in or what to do.” (P7)

Patients in the nonuser group stated that, to their knowledge, they were not given a choice about whether they wanted an RM system. To the question, “Were you told you were going to get a remote monitoring system?” 1 participant replied:

“ No; it showed up one day! ” (P6)

No one in the nonuser group reported having a conversation with a health care professional about the RM system’s purpose or function. Only 1 patient in the nonuser group reported knowing the brand of RM system.

Patterns of Use

Users

Several patients expressed how easy the system was to use. Convenience also appeared to be a major driver of usage:

“…if it cuts down on the times you have to go in. You can do a lot of it from home. It is convenient in a lot of ways. They [health care professionals] have all the information right in front of them…” (P1)

The RM system had the positive effect of making the users feel more secure. One patient referred to the RM system as a “security blanket”:

“ Well, I just know if anything happened, you know, it would probably save my life.” (P4)

However, some patients expressed initial concern as to whether the data transmissions could be trusted.

“ Well, when they first mentioned it to me, I thought I didn’t know if I trusted it.” (Wife of P2)

Trust in the RM system seemed to come with time and with knowing other people who were taking this approach to care. When asked if they were concerned about whether the system would adversely affect their ICD, the patients stated they had never considered the issue.

Nonusers

Only 1 patient in the nonuser group said that a health care professional had called because the RM system was not being used. Nonuse was largely attributed to not understanding the purpose of the RM system. Other patients indicated that they preferred in-clinic device checks:

“ I really don’t mind coming in and having it checked.” (P9)

Several patients remarked they were “intimidated” by the system setup process. Confidence appeared to be a driver of whether patients were inclined to use RM. Patients who were not comfortable with the technology were resistant to believing RM could actually monitor their heart conditions:

“ I’m not too mechanical anyway, and I thought, ‘oh my God, I have to go through this and I’m going to trust this will work.’” (P8)

For some participants, lack of resources was an issue: 2 patients in the nonuser group said they did not have phone lines to perform device transmissions. Four patients reported setting up the RM system eventually (eg, 1 patient did so 1 year after receiving the system), but all 4 used the RM system only once.

Perspectives

Users

Patients in the user group appeared to be accepting and trusting of new technologies and open to innovation:

“ I’m thankful for any technology.” (P3)

The RM systems were perceived to be advantageous because patients believed that they were being constantly monitored. RM provided peace of mind for patients, who likened the technology to having a health care professional on standby. Patients stated that RM increased their sense of security and lessened anxiety.

“ It gets you more freedom of doing things, to where you don’t really have to almost watch everything you do. They are watching you, in a way.” (P5)

Of note, some patients in the user group expressed curiosity about the abilities of the RM systems and the breadth of the system’s data capture. References to “Big Brother” were made by several patients, suggesting that by using the technology they willingly subjected themselves to being watched by device companies and their health care professionals:

“…they had a printout at the clinic and they can tell the days that you exercise and the days that you don’t exercise. And everything is right there. Big Brother is watching. [Laughs] ” (P1)

Users appeared to be in awe—as opposed to in fear—of the RM system’s capabilities. In general, patients in the user group trusted their RM systems to transmit signals correctly and believed that the systems provided freedom and security.

Nonusers

A common theme among the nonusers was the belief that clinic visits were psychologically advantageous for patients. Patients described health care as a human discipline requiring social interchange. To them, new technology seemed to threaten the essence of health care as 1 human being caring for another.

“ I guess every time I come in, I always have a couple more questions to ask about something. And I think that [coming in] is important for the psychology of the patient, really. Because we are human beings…” (P6)

Clinic visits also appeared to allay uncertainty that patients had about whether their RM systems were working properly. Overwhelmingly, these patients trusted health care professionals over technology when it came to managing their health:

“ think hands on is important too. Talking with the people and knowing that the device is working properly, I think that is important…. the remote monitoring system doesn’t always answer all your questions…I don’t know. If I didn’t do it right, would it read it right or read it wrong? ” (P7)

Nonusers appreciated the opportunity to ask questions and felt comforted by verbal confirmation of ICD interrogation results that the health care professionals provided.

Perceptions of Usefulness

Users

Transportability and placement of the RM system in the home appeared to be challenging for some patients in the user group (eg, wiring configurations external to the home, weight and size of the system).

“ If we are just gone for a few days, I don’t take it. I don’t worry. I don’t even think about it.” (P1)

Even after encountering logistical difficulties with their RM systems, the patients’ opinions about the usefulness of the systems were unchanged:

“ Oh boy! In my own case, I couldn’t think of any reason why you would not use it.” (P3)

Ease of use, fewer clinic visits, and the perception of continuous monitoring gave patients the impression that the RM technology was worth using. For participants in the user group, RM systems were viewed as providing “freedom” and characterized as “surprising,” “amazing,” and “smart.”

Nonusers

All of the nonusers we spoke with admitted that there could be a benefit to using RM systems:

“ I guess it is a pro being you don’t have to go down to the clinic, to that floor, have somebody working with you. The pro is more for [the clinic] than it is for me.” (P9)

The usefulness of RM systems from the perspectives of nonusers was tempered by some distrust of the technology but, mostly, by the patients’ own preference for clinic visits:

“ I thought, ‘God, you know, as close as we are down here to the clinic, why don’t I just go down and have them check it there? ’” (P8)

The patients in this study lived near the academic medical center, which may have enhanced their willingness to travel for clinic visits. Nevertheless, they expressed that the “personal” feel of clinic visits was the driving force for preferring clinic visits over the RM system for device follow-up.

Recommendations

Users

Patients in the user group appeared satisfied with the features of their RM system. Nevertheless, patients recommended changes to RM systems (Box 2). For example, 1 patient recommended that device companies develop means for patients to be able to use their cell phones as RM system transmitters while traveling:

“ [A] way to [make the RM system] easier to take with you when you traveled on shorter excursions…. maybe some way you could use a cell phone.” (P1)

Some patients questioned the cost-effectiveness of RM systems and were unsure what was covered by Medicare. Patients’ experiences varied in this regard. Some reported having the billing of their RM system “taken care of” (P1), yet others remarked “you need to be your own advocate, attorney” (P3). The patients with whom we spoke agreed that others would benefit from knowing up front the coverage policies for RM systems.

Nonusers

Confirmation that the RM system was working properly was important to nonusers. Suggestions for improving RM systems included adding a confirmation feature (eg, a blinking light) to show patients that their transmission was sent and received:

“ When you transmit, you like to know they actually received it.” (P8)

Patients also wanted to know that the device company or their health care provider would let them know if a transmission did not go through. A specific protocol outlining follow-up procedures in case of a system malfunction would be helpful and lessen patient anxiety:

“ See, now mine didn’t do that…mine doesn’t say anything so I had no idea whether I had done it right or wrong.” (P7)

Enhanced customer service would help patients feel adequately supported through the RM system. Help lines should be the norm. Call center associates should be well versed in the function of RM systems and be prepared to answer patient questions with comprehensible explanations.

“ I was more apprehensive after I had talked with the people [at the device company] than if I hadn’t called at all. So, I don’t know, when you call that number, I just assumed that those people are more knowledgeable… I know where to call, but the answers I got when I did was ‘Huh? ’” (P8)

All participants in the nonuser group encouraged clinics that use RM systems to not undervalue the importance of preserving relationships with their patients. RM systems should not be viewed as a replacement for person-to-person communication. Rather, RM should serve to support the care process with information to inform decision making.

“ I think the personalization is a little better when you are physically sitting there talking to somebody. And you listen more. You pay more attention to what somebody is saying when they look at you and you can see the earnestness in their face…” (P6)

Face-to-face interactions with their health care professionals were important to patients in the nonuser group despite their attitude toward the RM system.

Discussion

Our research suggests that different perceptions and experiences occur among patients with ICDs who received RM systems. Prior research supports our finding that impediments to RM use exist (28). In our study, patients in the user group showed an affinity for technology and openness to innovation. Patients also were found to be more likely to use their RM system if they spoke with their health care professional about the functions and benefits of using the technology, especially early on in their care. One study suggests that patients’ relationship with their health care professional is crucial to adherence (10).

RM users vs nonusers reported having a conversation with their health care professional before receiving the RM system. Likewise, several patients in the user group were given the option of accepting the RM system. In contrast, patients in the nonuser group generally reported that they did not learn about the RM system before receiving one. They almost never were given a choice on whether they preferred RM over clinic visits.

Both users and nonusers mentioned being “intimidated” to some degree by the RM system. It appeared that communication with a health care professional or an industry representative about the RM system helped patients to gain confidence in using the system. Although lack of resources (eg, a phone line) affected some patients in the nonuser group, not understanding the function of the technology tended to overtly impact their experience. Misperceptions about how RM may impinge on a patient’s personal privacy were not uncommon (12). Furthermore, patients in the nonuser group had a pervasive fear that RM systems represented an inexorable momentum toward technologizing or depersonalizing all of health care. Increased use of technology like the RM systems was thought to have a negative impact on a patient’s relationship with his or her health care professional. Research has showed that some patients fear RM will “prevent them from seeing their doctor” (9). Of note, other investigators have argued that having RM data available can facilitate decision making between health care professionals and patients (29).

Our findings reinforce recommendations that physicians, allied health personnel, and industry representatives provide education perioperatively and at first postimplant office visits, to promote use of RM (28). Allied health staff should follow up with nonusers and reinforce the value of RM with each contact. Giving patients the option to decline an RM system would likely not overburden the health care providers but could help preserve resources by not providing the technology to patients who are unlikely to comply with utilization of the system or who simply elect for clinic visits. A patient’s comfort level with technology in general provides some clues to the likelihood of the patient using an RM system, as does the patient’s desire in having a close relationship with his or her health care professional in person.

Our patients suggested increasing the transportability of the RM systems and upgrading the RM technology to serve patients who are highly mobile. Both groups agreed that enhancing confirmation features of the RM system would benefit patients by increasing their sense of security about the accuracy of their transmission. Simple changes, such as a solid light representing transmission success, would help patients know when to call their health care professional for follow-up in the event of a malfunction. Strong customer service appears to be most important to patients whether or not they are naturally inclined to adopt RM technology. The Heart Rhythm Society states that the value of communication between health care professionals and patients who use RM should not be overlooked (30).

Our study found that the usability of RM systems could be improved by making small changes to existing processes and modifying system features. The qualitative methodology used in this study encouraged patients to expand on ways to personalize the electronic monitoring experience. In response, we encourage health care providers to discuss with RM recipients the ways RM can support, rather than impinge, on their relationships with their clinical providers. Likewise, device companies should consider enhancing current system features, such as transmission confirmation, to increase patient confidence. Future research should involve patients from other regions and of diverse age, sex, marital status, and race. Our qualitative results may also be used to inform quantitative studies, such as surveys. Additional studies looking at how to integrate RM with other familiar technologies, such as smartphones, could promote use of RM. Other research should investigate ways in which social support—patient-to-patient education or online forums—can promote adherence with RM.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. Recruitment of study patients in the surrounding county restricted our ability to include patients from diverse racial backgrounds. Few patients were female and all patients were aged 58 years or older. Overall, our patient sample included white, married patients from a single academic medical center in a Midwestern state, which likely impacts the generalizability of our findings. We looked only at RM systems used by the academic medical center. Since only a small number of patients were available for study, our research was limited to 2 focus groups. Despite the study reaching data saturation, readers should interpret our findings with caution because of the small number of patients and the high degree of sample homogeneity. Nevertheless, the study results provide a descriptive account of how device companies and health care professionals who care for patients with an ICD may improve and better use the RM systems. To our knowledge, there is no validated instrument for assessing the perspectives of patients who use RM.

Conclusion

Patients who have received an RM system for management of an ICD are more likely to use the system if its purpose and function have been thoroughly explained. Early discussions about RM systems and access to help lines might allay patient fears by providing a human dimension to technology-managed care. Design changes to RM systems oriented toward enhancing confirmation features and providing feedback should be considered for their ability to make patients more comfortable and to increase adherence. Health care professionals and the device industry should communicate with patients early and often about the assumed benefits of using RM systems and should be vigilant about addressing barriers to use.

Box 1. Major Themes of Patient Experiences Related to Remote Monitoring Systems.

First encounters

Patterns of use

Perspectives

Perceptions of usefulness

Recommendations

Box 2. Recommendations of Patients for Use of Remote Monitoring Systems.

Engage early in conversations with health care provider about the remote monitoring technology

Increase the system’s transportability

Upgrade the technology to provide wireless capabilities

Enhance the confirmation features on sending data remotely

Strengthen customer service

Abbreviations

- ICD

implantable cardioverter-defibrillator

- RM

remote monitoring

- TRUST

Lumos-T Safely Reduces Routine Office Device Follow-up

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: Mss Ottenberg and Gerhardson, and Dr Swetz and Mr Mueller have no conflict of interest. Dr Mueller is a member of the Boston Scientific Patient Safety Advisory Board and also writes for Journal Watch.

References

- 1.Buch E, Boyle NG, Belott PH. Pacemaker and defibrillator lead extraction. Circulation. 2011 Mar 22;123(11):e378–e380. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.987354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kusumoto F, Goldschlager N. Remote monitoring of patients with implanted cardiac devices. Clin Cardiol. 2010 Jan;33(1):10–17. doi: 10.1002/clc.20688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ricci RP, Morichelli L, Santini M. Home monitoring remote control of pacemaker and implantable cardioverter defibrillator patients in clinical practice: impact on medical management and health-care resource utilization. Europace. 2008 Feb;10(2):164–170. doi: 10.1093/europace/eum289. Epub 2008 Jan 16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raatikainen MJ, Uusimaa P, van Ginneken MM, Janssen JP, Linnaluoto M. Remote monitoring of implantable cardioverter defibrillator patients: a safe, time-saving, and cost-effective means for follow-up. Europace. 2008 Oct;10(10):1145–1151. doi: 10.1093/europace/eun203. Epub 2008 Aug 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heidbüchel H, Lioen P, Foulon S, Huybrechts W, Ector J, Willems R, Ector H. Potential role of remote monitoring for scheduled and unscheduled evaluations of patients with an implantable defibrillator. Europace. 2008 Mar;10(3):351–357. doi: 10.1093/europace/eun010. Epub 2008 Feb 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schoenfeld MH, Compton SJ, Mead RH, Weiss DN, Sherfesee L, Englund J, et al. Remote monitoring of implantable cardioverter defibrillators: a prospective analysis. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2004 Jun;27(6 Pt 1):757–763. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2004.00524.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Varma N, Stambler B, Chun S. Detection of atrial fibrillation by implanted devices with wireless data transmission capability. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2005 Jan;28(Suppl 1):S133–S136. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2005.00083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Varma N, Pavri B, Stambler B, Michalski J. TRUST Investigators. Effect of transmission reliability on remote follow up in ICD patients: automatic home monitoring in the TRUST trial [abstract] Europace. 2011;13(3) Abstract P1026. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Epstein LM, Shea JB. Practical considerations for remote monitoring. Congest Heart Fail. 2008 Sep-Oct;14(5) Suppl 2:25–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7133.2008.tb00017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ricci RP, Morichelli L, Quarta L, Sassi A, Porfili A, Laudadio MT, et al. Long-term patient acceptance of and satisfaction with implanted device remote monitoring. Europace. 2010 May;12(5):674–679. doi: 10.1093/europace/euq046. Epub 2010 Mar 2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stoepel C, Boland J, Busca R, Saal G, Oliveira M. Usefulness of remote monitoring in cardiac implantable device follow-u. Telemed J E Health. 2009 Dec;15(10):1026–1030. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2009.0068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matlock DD. Big Brother is watching you: what do patients think about ICD home monitoring? Circulation. 2010 Jul 27;122(4):319–321. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.966515. Epub 2010 Jul 12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Landolina M, Perego GB, Lunati M, Curnis A, Guenzati G, Vicentini A, et al. Remote monitoring reduces healthcare use and improves quality of care in heart failure patients with implantable defibrillators: the evolution of management strategies of heart failure patients with implantable defibrillators (EVOLVO) study. Circulation. 2012 Jun 19;125(24):2985–2992. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.088971. Epub 2012 May 24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raatikainen MJ, Uusimaa P, van Ginneken MM, Janssen JP, Linnaluoto M. Remote monitoring of implantable cardioverter defibrillator patients: a safe, time-saving, and cost-effective means for follow-up. Europace. 2008 Oct;10(10):1145–1151. doi: 10.1093/europace/eun203. Epub 2008 Aug 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crossley GH, Boyle A, Vitense H, Chang Y, Mead RH. CONNECT Investigators. The CONNECT (Clinical Evaluation of Remote Notification to Reduce Time to Clinical Decision) trial: the value of wireless remote monitoring with automatic clinician alerts. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011 Mar 8;57(10):1181–1189. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.12.012. Epub 2011 Jan 20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bikou O, Licka M, Kathoefer S, Katus HA, Bauer A. Cost savings and safety of ICD remote control by telephone: a prospective, observational study. J Telemed Telecare. 2010;16(7):403–408. doi: 10.1258/jtt.2010.090810. Epub 2010 Sep 24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ricci RP, Morichelli L, Santini M. Remote control of implanted devices through Home Monitoring technology improves detection and clinical management of atrial fibrillation. Europace. 2009 Jan;11(1):54–61. doi: 10.1093/europace/eun303. Epub 2008 Nov 16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Varma N, Epstein AE, Irimpen A, Schweikert R, Love C. TRUST Investigators. Efficacy and safety of automatic remote monitoring for implantable cardioverter-defibrillator follow-up: the Lumos-T Safely Reduces Routine Office Device Follow-up (TRUST) trial. Circulation. 2010 Jul 27;122(4):325–332. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.937409. Epub 2010 Jul 12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Myrvang H. Automatic remote home monitoring is a safe option for ICD follow-up. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2010 Oct;7(10):541. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2010.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saxon LA, Hayes DL, Gilliam FR, Heidenreich PA, Day J, Seth M, et al. Long-term outcome after ICD and CRT implantation and influence of remote device follow-up: the ALTITUDE survival study. Circulation. 2010 Dec 7;122(23):2359–2367. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.960633. Epub 2010 Nov 22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Al-Khatib SM, Piccini JP, Knight D, Stewart M, Clapp-Channing N, Sanders GD. Remote monitoring of implantable cardioverter defibrillators versus quarterly device interrogations in clinic: results from a randomized pilot clinical trial. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2010 May;21(5):545–550. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2009.01659.x. Epub 2009 Dec 15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mann CJ. Observational research methods. Research design II: cohort, cross sectional, and case-control studies. Emerg Med J. 2003 Jan;20(1):54–60. doi: 10.1136/emj.20.1.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patton MQ. Qualitative research and evaluation methods. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage Publications; c2002. p. 598. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Denzin NK, Lincoln YS. Handbook of qualitative research. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage Publications; c2000. p. 1,065. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Strauss AL. Qualitative analysis for social scientists. Cambridge (UK): Cambridge University Press; 1987. p. 319. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L. How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods. 2006 Feb;18(1):59–82. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Movsowitz C, Mittal S. Remote patient management using implantable devices. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2011 Jun;31(1):81–90. doi: 10.1007/s10840-011-9548-2. Epub 2011 Feb 17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Afolabi BA, Kusumoto FM. Remote monitoring of patients with implanted cardiac devices: a review. Eur Cardiol. 2012;8(2):88–93. doi: 10.1002/clc.20688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilkoff BL, Auricchio A, Brugada J, Cowie M, Ellenbogen KA, Gillis AM, et al. Heart Rhythm Society; European Heart Rhythm Association; American College of Cardiology; American Heart Association; European Society of Cardiology; Heart Failure Association of ESC; Heart Failure Society of America. HRS/EHRA expert consensus on the monitoring of cardiovascular implantable electronic devices (ICDs): description of techniques, indications, personnel, frequency and ethical considerations. Heart Rhythm. 2008 Jun;5(6):907–925. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2008.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]