Abstract

The integral interaction of signaling components in the regulation of visceral inflammation-induced central sensitization in the spinal cord has not been well studied. Here we report that phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)-dependent Akt activation and N-Methyl-D-aspartic acid receptor (NMDAR) in lumbosacral spinal cord independently regulates the activation of cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) in vivo in a rat visceral pain model of cystitis induced by intraperitoneal injection of cyclophosphamide (CYP). We demonstrate that suppression of endogenous PI3K/Akt activity with a potent PI3K inhibitor LY294002 reverses CYP-induced phosphorylation of CREB, however, it has no effect on CYP-induced phosphorylation of NR1 at Ser897 and Ser896; conversely, inhibition of NMDAR in vivo with MK801 fails to block CYP-induced Akt activation but significantly attenuates CYP-induced CREB phosphorylation in lumbosacral spinal cord. This novel interrelationship of PI3K/Akt, NMDAR, and CREB activation in lumbosacral spinal cord is further confirmed in an ex vivo spinal slice culture system exposed to an excitatory neurotransmitter calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP). Consistently we found that CGRP-triggered CREB activation can be blocked by both PI3K inhibitor LY294002 and NMDAR antagonists MK801 and D-AP5. However, CGRP-triggered Akt activation cannot be blocked by MK801 or D-AP5; vice versa, LY294002 pretreatment that suppresses the Akt activity fails to reverse CGRP-elicited NR1 phosphorylation. These results suggest that PI3K/Akt and NMDAR independently regulates spinal plasticity in visceral pain model, and target of a single pathway is necessary but not sufficient in treatment of visceral hypersensitivity.

Keywords: Akt, NMDAR, CREB, spinal cord, central sensitization

BACKGROUND

The molecular mechanism underlying visceral pain is largely unclear; this hinders the development of effective therapeutic strategies. Visceral pain secondary to visceral inflammation is accompanied with increased levels of neurotransmitters and elevated neuronal activity in the primary afferent pathways (Benemei et al., 2009; Qiao and Grider, 2009; Chen et al., 2010). Release of excitatory neurotransmitters at the spinal dorsal horn can induce considerable neuronal plasticity in the spinal cord causing spinal central sensitization (Seybold, 2009). The molecular basis of central sensitization in the spinal cord may involve subsequent activation of intracellular signaling pathways and gene transcription (Gebhart et al., 2002; Honore et al., 2002; Landau et al., 2007; Okajima and Harada, 2006). We previously reported that the excitatory neurotransmitter calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) was enriched in the primary afferent neurons during visceral inflammation including cystitis and colitis (Yu et al., 2012; Qiao and Grider, 2009), and release of CGRP to the spinal cord activated the serine/threonine protein kinase Akt (Qiao and Grider, 2009). Along with this line of research, this study aims to characterize whether the Akt pathway is involved in the regulation of spinal plasticity during visceral inflammation.

Akt is traditionally considered as a survival factor targeting Bcl proteins, pro-caspase and Forkhead (Amaravadi and Thompson, 2005; Manning and Cantley, 2007), and is recently recognized as an essential component in sensory hypersensitivity in several animal models including cystitis-induced bladder hyperactivity and chemical or nerve injury-evoked somatic hypersensitivity (Arms and Vizzard, 2011; Sun et al., 2006; Xu et al., 2007; Pezet et al., 2008; Xu et al., 2011; Choi et al., 2010). The activity of Akt is regulated by phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)-facilitated formation of phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate (PIP3) which results in Akt trafficking and activation (Toker and Newton, 2000). In the central nervous system, PI3K is a key mediator in the regulation of synaptic plasticity and long-term potentiation (LTP) (Kelly and Lynch, 2000; Lin et al., 2001; Man et al., 2003). Recent studies show that inhibition of PI3K with LY294002/wortmannin significantly attenuates peripheral inflammatory or nerve injury pain (Sun et al., 2006; Xu et al., 2007; Pezet et al., 2008). In cystitis- induced visceral pain model, inhibition of Akt reduces bladder overactivity (Arms and Vizzard, 2011). These results suggest a critical role of Akt in the regulation of peripheral/visceral hypersensitivity.

A recent study in a formalin-induced hyperalgesia model shows that inhibition of the PI3K/Akt pathway blocks inflammation-induced phosphorylation of NR2 subunit of the N-Methyl-D-aspartic acid receptor (NMDAR) in the spinal cord (Pezet et al., 2008). NMDAR plays a key role in synaptic plasticity and central sensitization in the spinal cord under several physiologic and pathophysiologic conditions (Kohno et al., 2008; van der Heide et al., 2005; Xuet al., 2010). NMDAR forms a heterotetramer composed of two NR1 and two NR2 subunits (Li and Tsien, 2009). The activity of the NMDAR is modulated by phosphorylation of the NR1 subunit (Masu et al., 1993; Mori and Mishina, 1995) at Ser890 and Ser896 by protein kinase C (PKC) and at Ser897 by protein kinase A (PKA) (Tingley et al., 1997; Zou et al., 2002) leading to Ca2+ influx and Ca2+ dependent physiological effects. Among NMDAR-regulated pathways, the prosurvival signaling is mediated by the PI3K/Akt cascades and involves Ca2+ dependent cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) activation in several neuronal types in culture (Hetman and Kharebava, 2006). As for CREB activation, a list of kinases including Akt are able to phosphorylate CREB at Ser133 and regulate CRE-mediated gene transcription (Johannessen et al., 2004; Gonzalez and Montminy, 1989). Several studies demonstrate that the phosphorylation level of CREB is increased in the spinal cord in inflammatory and neuropathic pain (Anderson and Seybold, 2000; Ji and Rupp, 1997; Miletic et al., 2002).

Although the role of the PI3K/Akt, NMDAR and CREB pathways in synaptic plasticity has been suggested, the temporospatial patterns of these intracellular components and their interrelationships in signal transduction in lumbosacral spinal cord especially in visceral inflammation-induced spinal plasticity is not clear. In the present study we combined in vivo cystitis animal model and ex vivo spinal culture approaches and found that the PI3K/Akt pathway and the NMDAR pathway act independently in regulating the activity of transcription factor CREB, a multifaceted regulator of neuronal plasticity in visceral pain model. Neural retrograde tracing demonstrates that the primary afferent neurons that receive the urinary bladder sensory input are located in the L1, L2, L6 and S1 segments (Qiao and Grider, 2007). Thus, these segments of spinal cord were used in the current study to characterize the interrelationship of the Akt and NMDAR and their roles in spinal plasticity following CYP-induced cystitis.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Animals and Reagents

Adult male rats (150-200 g) from Harlan Sprague Dawley, Inc. (Indianapolis, IN) were used. All experimental protocols involving animal use were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the Virginia Commonwealth University. Animal care was in accordance with the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC) and National Institutes of Health guidelines. All efforts were made to minimize the potential for animal pain, stress, or distress as well as to reduce the number of animals used. Cyclophosphamide (CYP), β-actin antibody, and other chemicals used in this experiment were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Antibody against p-NR1 Ser897 was from Millipore (Lake Placid, NY). Antibodies for p-CREB, CREB, p-Akt, and Akt were from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). p-NR1 Ser896 antibody was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Secondary antibodies for western blot were from Pierce Biotechnology (Rockford, IL) and secondary antibodies for immunohistochemistry were from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR).

Induction of Cystitis

Cystitis was induced in rats by intraperitoneal injection of CYP at a single dose of 150 mg/kg body weight. The animals were allowed to survive for 8 or 48 hours (h). Control rats received volume-matched injections of saline. All injections were performed under isoflurane (2 %) anesthesia.

Tissue Collection

The spinal cord was dissected out and the segmental levels were identified. For western blot, the L1-L2 and L6-S1 spinal segments were separately homogenized in T-per buffer (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL) supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Sigma). For immunohistochemistry, the L1 and L6 spinal segments were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M PBS (pH=7.4) followed by 20% sucrose for cyoprotection. For acute culture, the L1-L2 and L6-S1 spinal segments were freshly dissected out from naïve animals and combined for treatment.

Western Blot

The protein extracts were subject to centrifugation at 20,200 g for 10 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant was removed to a fresh tube. The protein concentration was determined using Bio-Rad DC protein assay kit. Proteins were then separated on a 10% SDS-PAGE gel and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. The membrane was blocked with 5% milk in Tris-buffered saline for 1 h and then incubated with a specific primary antibody followed by HRP-conjugated secondary antibody. For internal loading control, the same membrane was stripped and re-probed with anti-β-actin antiserum or antibody to a non-phosphorylated form of the protein examined. The concentrations of antibodies used were: p-NR1: 1:1000; p-Akt and Akt: 1:1000; p-CREB and CREB: 1:1000; β-actin: 1:3000. The bands were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL). Densitometric quantification of the immunoreactive bands was performed using the software FluorChem 8800 (Alpha Innotech, San Leabdro, CA).

Immunohistochemistry

The spinal cord segments were sectioned transversely at a thickness of 30 μm and were immunostained by free-floating method. Generally, sections were incubated with blocking solution containing 5% normal donkey serum (Jackson Immuno Research, West Grove, PA) in PBST (0.3% Triton X-100 in 0.1 M PBS, pH 7.4) for 30 min followed by specific primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. After rinsing (3 × 10 min with 0.1 M PBS), tissues were incubated with fluorescence-conjugated species- specific secondary antibody for 2 h at room temperature. Following washing, the sections were mounted to slides and coverslipped with Citifluor (Citifluor Ltd., London). The sections were then viewed and analyzed with a Zeiss AxioImage Z1 Apitome fluorescent microscope.

The analysis of the immunoreactivity at the dorsal horn were done as previously reported (Qiao and Grider, 2009), by converting fluorescent images to a gray scale that ranged in intensity from 0 (black) to 255 (white) for the purpose of densitometry. The same number of standard sized rectangles was overlaid on the area of interest (i.e., superficial dorsal horn in this study) for each spinal section, with one rectangle chosen from the background staining area in the spinal cord for subtraction. Intensity measured within the rectangles was averaged as one point. The number of positive neurons in the rest of spinal laminae was counted in a blind fashion; each section was counted by two people and the numbers were averaged. 4 or 5 sections per animal were analyzed and the numbers were averaged and presented as one point.

Spinal Cord Culture

The spinal cord segments were transversely sectioned at a thickness of 250 μm with a tissue sectioner. The sections were randomly divided into several cell culture wells containing Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 200 units/mL penicillin, 200 mg/mL streptomycin, and 100 mg/mL gentamycin and cultured for 4-6 h. CGRP (250 nM) was added to the culture medium and incubated for 30 min. The length of incubation (30 min) was chosen based on our preliminary time course studies (data not shown). Tissues were then collected for western blot analysis. All cultures were maintained in a 10% CO2 environment at 37 °C.

Statistical Analysis

Comparison between control and experimental groups was made by using a one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's test or by Newman-Keuls Multiple Comparison Test. For in vivo experiments, 4-6 animals were used for each experimental group; for ex vivo experiments, 5 independent experiments were performed. Differences between means at a level of p≤0.05 were considered to be significant.

RESULTS

CYP cystitis-induced CREB activation in lumbosacral spinal cord was blocked by inhibition of the Akt activity in vivo

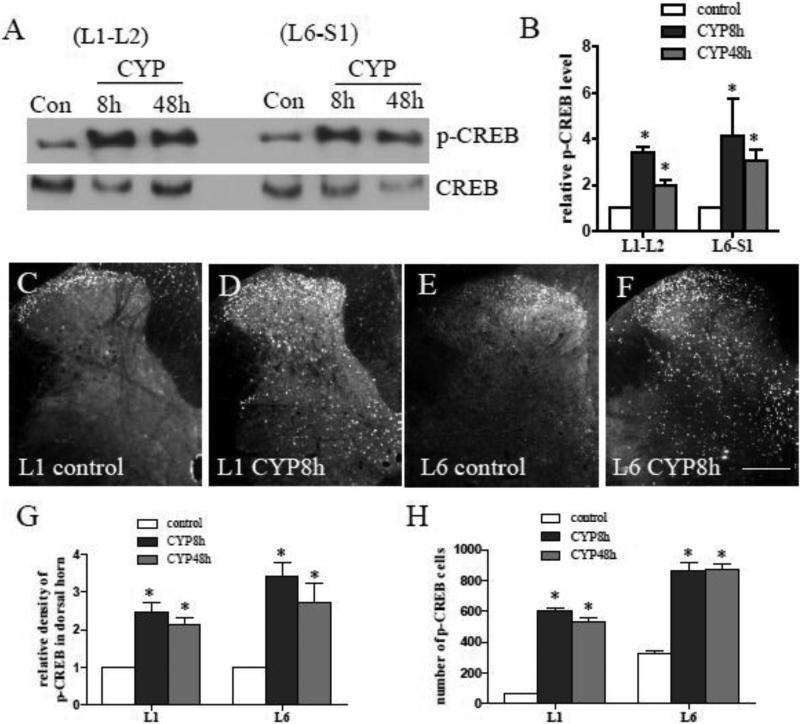

The transcription factor CREB occupies approximately 4,000 promoter sites in human tissues (Zhang et al., 2005). Its phosphorylation (p-CREB) on Ser133 (the active form of CREB) is implicated to function as a molecular switch underlying neuronal plasticity (Lonze and Ginty, 2002). Peripheral inflammation-induced spinal plasticity is shown as increased CREB phosphorylation in the spinal cord (Ji and Rupp, 1997) . In CYP-induced cystitis, the level of p-CREB was also increased in the lumbosacral spinal segments L1-L2 and L6-S1examined by western blot (Fig. 1A). Summary data (Fig. 1B) showed that p-CREB was significantly increased in these spinal segments at 8 h and 48 h post CYP treatment. Immunohistochemistry results revealed that the p-CREB immunoreactivity (Fig. 1C-F) was increased in the dorsal horn region and in the deep laminae of the spinal cord examined at both 8 h and 48 h post CYP induction (Fig. 1G-H), and demonstrated as nuclear staining.

Figure 1. Up-regulation of CREB activity in the spinal cord during cystitis.

At 8 or 48 h after CYP treatment, the level of p-CREB was increased in the rostral lumbar L1-L2 and the lumbosacral L6-S1 spinal cord examined by western blot (A). Histogram (B) showed relative levels of p-CREB in spinal segments examined. Immunostaining (C-F) showed that cystitis-induced p-CREB immunoreactivity was increased in the spinal dorsal horn (G) as well as in the cells in deep laminae (H). Results were presented as mean ± SE from 5-6 animals at each time point. *, p < 0.05 vs control. Bar=250 μm.

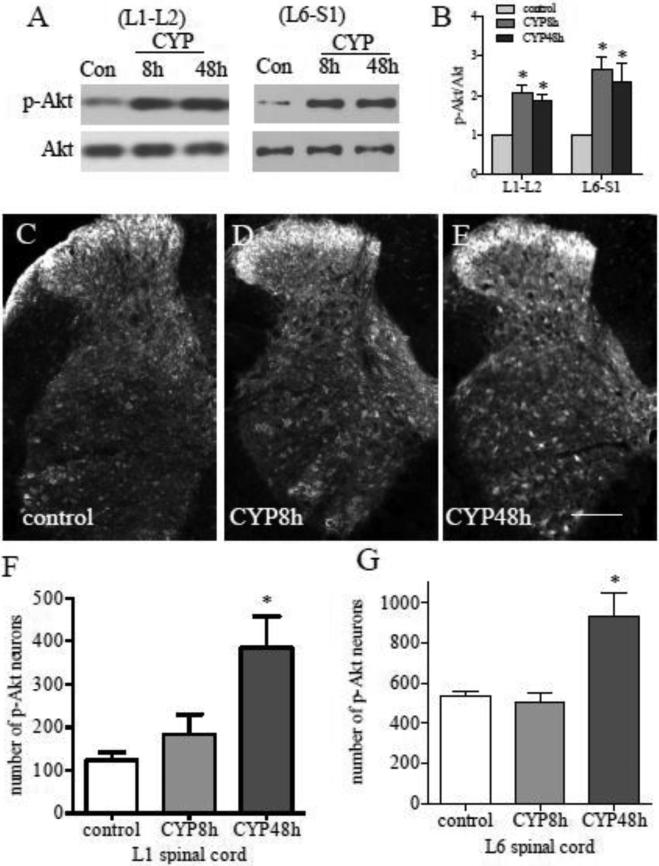

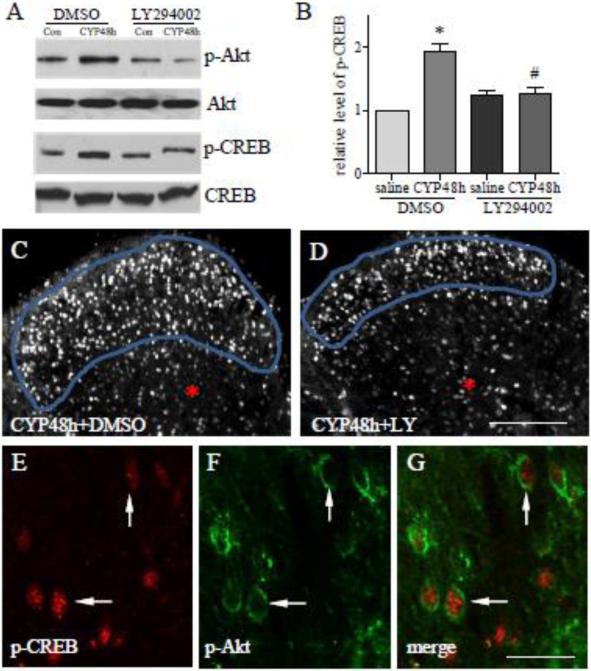

The signaling pathways that regulate CREB activity in lumbosacral spinal cord have not been fully studied. A list of kinases including Akt is able to phosphorylate and activate CREB in many systems (Johannessen et al., 2004). In CYP-induced cystitis, the phosphorylation level of Akt (p-Akt) at Ser473 was increased in the L1-L2 and L6-S1 spinal cord at 8 and 48 h post CYP treatment (Fig. 2A-B), indicating an activation of the Akt pathway. Following CYP treatment, p-Akt was increased in the superficial dorsal horn at 8 h and in the regions of deep laminae as well as in the ventral horn at 48 h post CYP injection (Fig. 2C-G). To examine whether Akt has a role in CYP-induced CREB activation, we injected the animals with a potent PI3K inhibitor LY294002 at a dose of 50 μg/kg body weight (i.p.) immediately after CYP injection. Phosphorylation of Akt at Ser473 is often regulated by PI3K activation (Datta et al., 1999; Alessiet al., 1996), and is necessary for the catalytic activity of Akt (Datta et al., 1999). As expected, LY294002 suppressed the endogenous Akt activity caused by CYP-induced cystitis (Fig. 3A upper two panels showed L6 spinal cord). Western blot also showed significant inhibition of CREB activity by LY294002 examined in L6 spinal cord in CYP-treated animals (Fig. 3A lower two panels, and summary 3B). Immunohistochemistry showed that the inhibition of CREB activity by LY294002 mainly occurred in the region of dorsal horn (compare Fig. 3D to C, circled area). This may be due to different distribution patterns of p-Akt and p-CREB in the spinal cord by which p-Akt was increased in the deep laminae and ventral horn at 48 h but not 8 h (Fig. 2F-G), while p-CREB was increased in these regions at both 8 h and 48 h post CYP injection (Fig. 1H). In the dorsal horn region, p-Akt positive neurons also expressed p-CREB (Fig. 3E-G, white arrows) during CYP-induced cystitis.

Figure 2. Up-regulation of p-Akt in the spinal cord during cystitis.

At 8 or 48 h after CYP treatment, the level of p-Akt was increased in both L1-L2 and L6-S1 spinal segments examined by western blot (A, summary data B). Immunostaining (C-E) showed that at 8 h post CYP injection, the p-Akt was increased in the region of the superficial dorsal horn (D). At 48 h post CYP injection, the p-Akt immunoreactivity was expressed in both dorsal horn and deep laminae (E). The total number of spinal cells expressing p-Akt was significantly increased in the lumbosacral spinal cord at 48 h post CYP injection (F and G). Results were presented as mean ± SE from 4-6 animals at each time point. *, p < 0.05 vs control. Bar=250 μm.

Figure 3. Attenuation of cystitis-induced CREB phosphorylation by PI3K inhibitor LY294002.

Western blot showed that suppression of the endogenous Akt activity (A upper) by LY294002 attenuated cystitis-induced CREB activation (A, bottom; B). Immunohistochemistry showed that inhibition of p-CREB in the spinal cord by LY294002 in vivo occurred in the spinal dorsal horn (compare D to C, circled area) but not in the inner laminae of the spinal cord (red *). Double immunostaining showed that a subpopulation of spinal neurons (E-G, cells indicated by arrows) co-expressed p-CREB (E, red nuclear staining) and p-Akt (F, green). During cystitis, p-Akt was expressed close to the cell membrane of the spinal neurons (F, arrows) indicating that cystitis caused membrane trafficking of Akt, a critical step for Akt activation. Results were presented as mean ± SE from 4 independent experiments. Bar=125 μm in C-D; 20 μm in E-G. *, p<0.05 vs saline+DMSO; #, p<0.05 vs CYP+DMSO.

PI3K/Akt pathway failed to phosphorylate NR1 subunit of NMDAR in vivo

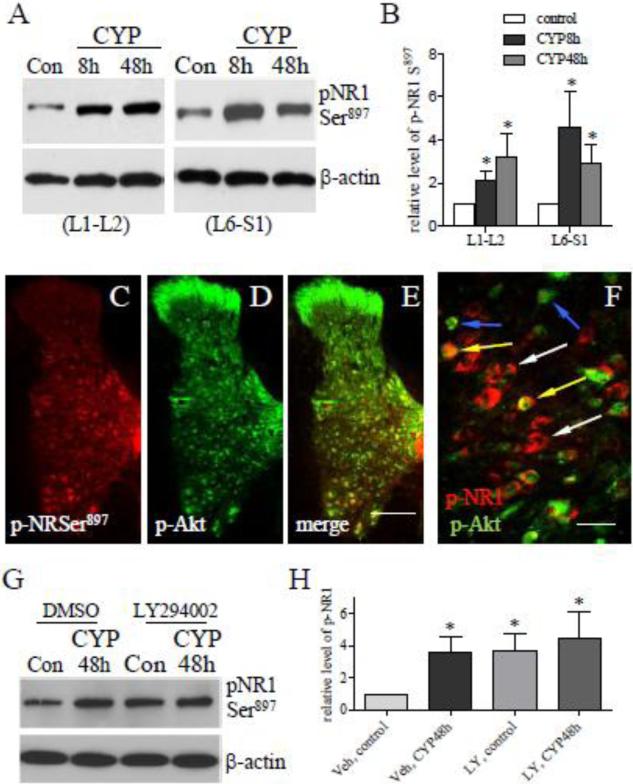

After CYP treatment, the phosphorylation level of the NR1 subunit of the NMDAR at Ser897 (the PKA site) was increased (Fig. 4A and B), and a subpopulation of the p-NR1 neurons expressed p-Akt (Fig. 4C-F, yellow arrows). NMDAR plays a prominent role in neuronal plasticity and contributes significantly to long-term potentiation (LTP), and its activity is modulated by NR1 and NR2 phosphorylation. It was reported that the phosphorylation of the NR2B subunit of the NMDAR was inhibited by LY294002 in Formalin-induced inflammatory pain model (Pezet et al., 2008). Thus we examined whether inhibition of the PI3K/Akt pathway was able to block NR1 phosphorylation in the spinal cord during CYP-induced cystitis. To our surprise, in LY294002-treated cystitic animals the phosphorylation level of p-NR1 Ser897 was not changed when compared to CYP and vehicle treatment examined in the L6 spinal cord (Fig. 4G; summary data Fig. 4H). We then examined that cystitis-induced NR1 phosphorylation at Ser896, the PKC site, was not affected by blockade of the PI3K/Akt pathway either (Fig. 5). In double immunostaining results (Fig. 4C-F), p-NR1 was mainly located in the deep laminae of the spinal cord, the large neurons at the nucleus dorsalis Clarke's column and the ventral horn region (Fig. 4C). It is apparent that this distribution pattern was very different from those of p-Akt (Fig. 4D). In deep laminae, some neurons that expressed p-NR1 (Fig. 4F, blue arrows) did not co-localize with p-Akt (Fig. 4F, white arrows).

Figure 4. Up-regulation of p-NR1 Ser897 in the spinal cord with cystitis and its interplay with p-Akt.

Western blot analysis showed that the levels of p-NR1 Ser897 (PKA site) were increased in the L1-L2 and L6-S1 spinal cord during cystitis (A, B). Immunohistochemistry showed that the cystitis-induced p-NR1 Ser897 was mainly located in the deep laminae of the spinal cord (C), and in the large neurons at the nucleus dorsalis Clarke's column and the ventral horn regions (C). Different from p-Akt (D), p-NR1 Ser897 was not expressed in the dorsal horn region, and was partially co-localized with p-Akt (F, yellow arrows; white arrows indicates p-NR1; blue arrows indicates p-Akt). Inhibition of Akt activity by LY294002 failed to block cystitis-induced up-regulation of pNR1 Ser897 examined in L6 spinal cord (G, H). Bar=200 μm in C-E; 15 μm in F. *, p<0.05 vs control. n=4-5 animals for each treatment.

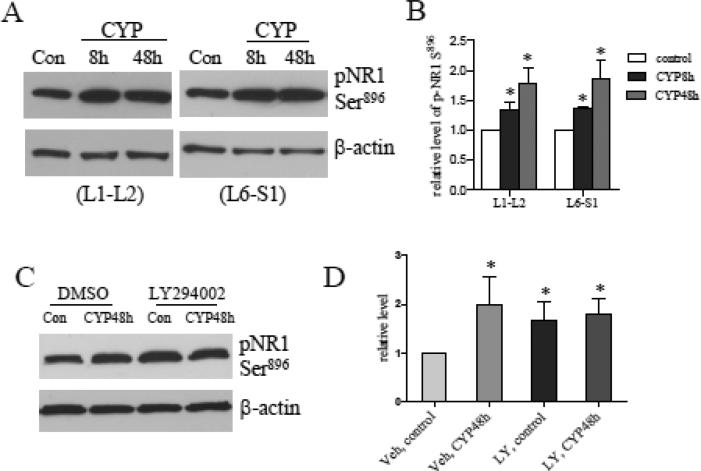

Figure 5. Cystitis-increased p-NR1 Ser896 levels were not regulated by the PI3K/Akt pathway.

The levels of p-NR1 Ser896 (PKC site) were increased in the L1-L2 and L6-S1 spinal cord during cystitis (A, B). Inhibition of Akt activity by LY294002 failed to block cystitis-induced up-regulation of pNR1 Ser896 examined in L6 spinal cord (C, D). *, p<0.05 vs control. n=4-5 animals for each treatment.

CYP cystitis-induced NMDAR activation regulated CREB but not Akt activity in the spinal cord

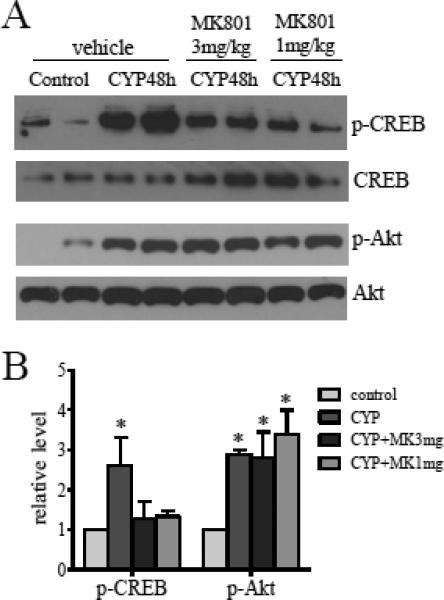

Activation of the NMDAR increases Ca2+ mobilization which may influence Ca2+ dependent signaling pathways thereby modulating CREB activity. To examine whether NMDAR has a role in CREB activation in the spinal cord during CYP-induced cystitis, we injected NMDAR antagonist MK801 at a dose of 3 mg/kg body weight or 1 mg/kg body weight (i.v.) to cystitic animals and found that inhibition of the NMDAR reversed CYP-induced CREB activation in lumbosacral spinal cord (Fig. 6A upper panels and 6C). In contrast, the same samples were examined for the p-Akt level and results showed that the phosphorylation levels of Akt were not affected by MK801 treatment (Fig. 6A lower panels and 6C).

Figure 6. NMDAR mediated CREB but not Akt activation in the spinal cord during cystitis.

The L6 spinal cord was examined for the effects of NMDAR antagonist MK801 on CREB and Akt phosphorylation during cystitis. Cystitis-induced CREB phosphorylation was attenuated by MK801 (3 mg/kg body weight and 1 mg/kg body weight); cystitis-induced Akt phosphorylation was not affected by inhibition of NMDAR. n=4 animals for each treatment. *, p<0.05 vs control.

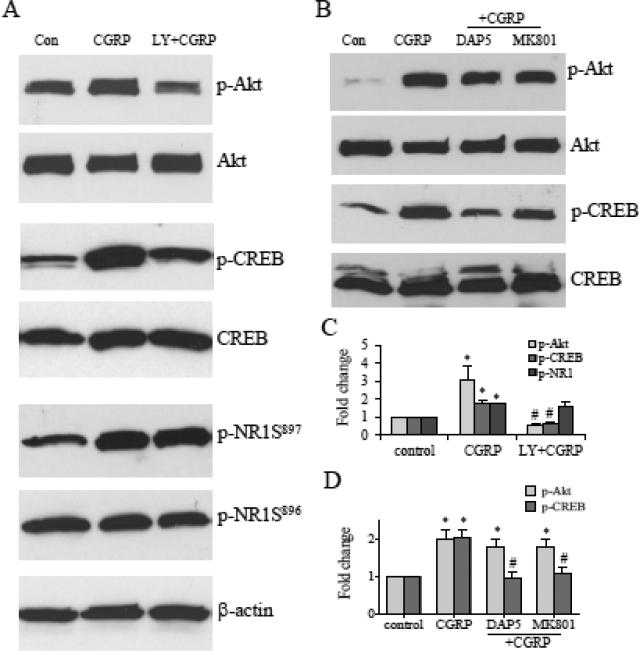

Akt and NMDAR regulated CREB activation in an independent manner in cultured spinal slices exposed to CGRP

The excitatory neurotransmitter CGRP is enriched in the sensory neuronal cell body in the DRG and is implicated to participate in central sensitization after release to the spinal cord. During CYP-induced cystitis, CGRP was increased in the DRG and in the Lissauer's tract in the dorsal horn (Vizzard, 2001). Treatment of spinal cord slices with CGRP increased Akt activity in culture (Qiao and Grider, 2009). To further examine the interplay of Akt, NMDAR and CREB, and confirm the above in vivo findings that PI3K/Akt and NMDAR independently regulated CREB activation in CYP cystitis-induced spinal plasticity, we treated the spinal slices with CGRP (250 nM) for 30 min, which also increased the levels of p-CREB and p-NR1 Ser897 (Fig. 7A, C).

Figure 7. Interrelationship of p-Akt, p-CREB and p-NR1 in the spinal cord examined in culture.

Treatment of spinal cord sections with CGRP increased the phosphorylation levels of Akt, CREB, and NR1 at Ser897 (A). Inhibition of Akt activity with the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 attenuated CGRP-induced CREB activation but not p-NR1 phosphorylation (A, C). Treatment with NMDAR antagonists DAP5 or MK801 failed to block CGRP-induced Akt activation but reversed CREB phosphorylation (B, D). Results were from 5 independent experiments. *, p<0.05 vs. control (vehicle); #, p<0.05 vs CGRP (+vehicle)-treatment.

The role of the PI3K/Akt pathway in CREB activation and p-NR1 phosphorylation was examined by pretreatment of the spinal cord with the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 (5 μM) and in the presence of CGRP. Consistent to in vivo findings, suppression of Akt activity blocked the p-CREB activation (Fig. 7A, C), but had no effect on NR1 phosphorylation at Ser897 (Fig. 7A, C). This suggested that Akt was an upstream kinase of CREB but was unable to lead to NR1 phosphorylation in the spinal cord (Fig. 8).

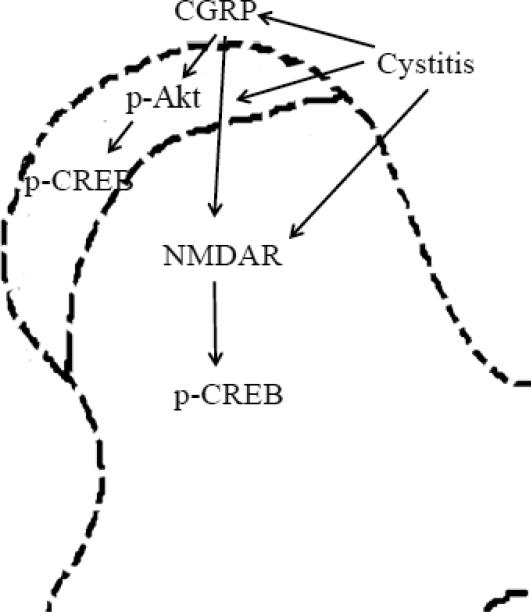

Figure 8. Schematic diagram illustrates the putative mechanism for cystitis- and CGRP-induced spinal plasticity involving novel interrelationship between CREB, Akt and NMDAR pathways.

Cystitis induces Akt activation in the dorsal horn region where it activates CREB. Cystitis also triggers NMDAR-mediated signaling in the deep laminae and leads to CREB activation. There is a lack of regulatory relationship between the PI3K/Akt and the NMDAR in the spinal cord during cystitis- and CGRP-induced spinal plasticity.

The role of NMDAR in CREB and Akt activation was examined by pretreatment of the spinal cord with NMDAR blockers D-AP5 (200 μM) and MK 801 (50 μM), and in the presence of CGRP. Consistent to in vivo findings, inhibition of NMDAR failed to block the evoked Akt activity (Fig. 7B, D), however reversed the elevated CREB phosphorylation in the spinal cord (Fig. 7B, D). This suggested that NMDAR regulated CREB activation independent of the Akt pathway (Fig. 8).

DISCUSSION

The neural plasticity and central sensitization in the spinal cord in response to peripheral irritation is manifest as transcriptional and translational regulation (Bradesi, 2010; Romero et al., 2013). The present study investigated the signaling pathways by which visceral inflammation (i.e. cystitis)-facilitated spinal plasticity shown as increased phosphorylation of transcription factor CREB in lumbosacral spinal cord was regulated by the PI3K/Akt pathway and NMDAR signaling. In the spinal cord, CYP-induced cystitis increased the phosphorylation levels of Akt, NR1 subunit of NMDAR and CREB, and inhibition of endogenous Akt blocked CYP cystitis- or CGRP-induced CREB activation but had no effect on the increased phosphorylation level of the NR1 subunit of the NMDAR. A recent study in an intraplantar Formalin model showed that the phosphorylation level of the NR2B subunit of the NMDAR was decreased in the spinal cord by a PI3K inhibitor (Pezet et al., 2008). These suggest that Akt-regulated NMDAR activity, if any, is unlikely through phosphorylating NR1 subunit. Vice versa, we found that inhibition of NMDAR with specific antagonist(s) blocked CYP cystitis- or CGRP induced CREB activity, however, had no effect on the level of Akt phosphorylation. These results suggest that the PI3K/Akt pathway and NMDAR act independently in the regulation of CREB activation, implicating a specific role of these pathways in visceral inflammation-induced spinal plasticity.

CREB as a target of multi-signaling pathways was activated in the spinal cord upon peripheral stimulation (Ji and Rupp, 1997; Messersmith et al., 1998; Anderson and Seybold, 2000; Ma and Quirion, 2001). Phosphorylation of CREB at Ser133 by protein kinases leads to the activation and subsequent binding of p-CREB to the promoter region of genes and promotes transcription. A number of kinases and genes in the CREB cascade, e.g., the Ca2+/CaM-dependent kinase II (CaMKII), PKA, and Akt that regulate the CREB activity (Gonzalez and Montminy, 1989; Sun et al., 1994; Du and Montminy, 1998; Johannessen et al., 2004); and neurokinin 1 receptor (Seybold et al., 2003) and TrkB (Kingsbury and Krueger, 2007) that are regulated by CREB activation, are associated with synaptic plasticity and LTP. Among the kinases and pathways that are able to phosphorylate and activate CREB, the PI3K/Akt pathway has been suggested to play a critical role in mediating sensory sensitization in response to peripheral inflammation or injury (Zhu and Oxford, 2007; Pezet et al., 2008). However, the role of the PI3K/Akt pathway in regulating CREB in the spinal cord in vivo is not studied. In the present study we found that in a visceral inflammatory pain model of CYP-induced cystitis, the CREB phosphorylation level was increased in the spinal cord, and inhibition of the PI3K/Akt pathway with the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 reversed cystitis- and CGRP-induced CREB phosphorylation in the spinal cord. A recent study shows that injection of a specific Akt inhibitor to cystitis animals is able to reverse bladder overactivity (Arms and Vizzard, 2011). These results suggest that the PI3K/Akt pathway has a critical role in regulating cystitis-induced spinal plasticity and bladder hyperactivity.

In the periphery, Akt is activated in the sensory neurons and regulates pain perception by activating TRPV1 receptor (Zhu and Oxford, 2007). In the present study we found that the Akt activity was also increased in the spinal cord which was regulated by the PI3 Kinase during CYP-induced cystitis. Akt activation in the spinal cord post CYP injection showed a similar spatial temporal pattern when compared to an animal model treated with intraplantar carrageenan to induce somatic pain. In both systems, Akt activity appeared in the superficial dorsal horn at acute phase post treatment and then in the deep laminae neurons after longer duration of drug treatment (Choi et al., 2010). One explanation of these region-specific dynamic changes could be the anatomic proximity of the dorsal horn neurons to the primary afferent neurons and nerve terminals that are immediately excited upon peripheral irritation. It is speculated that the activation of Akt in the deep laminae and/or ventral horn at a later phase of stimulation may be triggered directly or indirectly by pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF) release from spinal glial cells (Choi et al., 2010; Schafers and Sorkin, 2008) or due to a complex spino-bulbo-spinal pathway (Kovelowski et al., 2000; Suzuki et al., 2005). Several other important cytokines and inflammatory mediators in persistent pain are also well discussed (Taves et al., 2013) and may have roles in cystitis-induced spinal plasticity. Following noxious stimulation, excitatory neurotransmitters such as substance P and CGRP release centrally from the primary afferent neurons into the spinal dorsal horn (Duggan et al., 1988; Morton and Hutchison, 1989; Galeazza et al., 1995; Qiao and Grider, 2009) can also bind to their receptors and facilitate signal transduction such as activating the PI3K/Akt pathway (Qiao and Grider, 2009; Xu et al., 2011), and result in pain hypersensitivity (central sensitization) (Choi et al., 2012). The mechanism and contribution of peptides to central sensitization has been well discussed by Seybold (2009). It is noted that peptides such as substance P and CGRP are stored in large dense core vesicles of unmyelinated (C) and small myelinated (Aδ) terminals and their release are triggered by higher firing frequency-evoked intracellular Ca2+ concentration and/or by persistent stimuli (Durham and Masterson, 2013; Meng et al., 2009; Qin et al., 2008; Schweitzeret al., 1996); this is different from those for small molecule transmitters such as glutamate which is released from both large and small myelinated fibers and sometimes co-stored with substance P in regulation of nociception (De Biasi and Rustioni, 1988; Carozzi et al., 2008).

In addition to the PI3K/Akt pathway regulating CREB activity, a number of other kinases such as Ca2+/CaM-dependent protein kinases (CaMK), mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK) and PKA are also able to activate CREB in many systems (Du and Montminy, 1998; Gonzalez and Montminy, 1989; Johannessen et al., 2004; Sun et al., 1994). It has been reported that inhibition of the PKA pathway reversed somatic hyperalgesia and associated CREB activation in the spinal cord (Hoeger-Bement and Sluka, 2003). This could explain our results that at 8 h post CYP injection, CREB was activated in the deep laminae while Akt was not. Activation of PKA can lead to phosphorylation of the NR1 subunit of the NMDAR at Ser897 (Tingley et al., 1997) and modulate NMDAR activity. In cystitis animals, we showed that the phosphorylation level of NR1 at Ser897 was increased in the deep laminae and ventral horn of the spinal cord at 8 h and 48 h post CYP treatment. Calcium flux through NMDAR may regulate CREB activation in the spinal cord thereby contributing to cystitis - and CGRP-induced spinal plasticity. In inflammatory and neuropathic pain models, the NR1 phosphorylation is also enhanced in the spinal cord (Gao et al., 2005; Zou et al., 2000); in these studies, the antibodies used for NR1 phosphorylation are selective for either the Ser897 site alone or both the Ser897 and Ser896 sites together but not Ser896 alone. In our study we used specific antibodies to differentiate the Ser896 and Ser897 and found that both sites were phosphorylated in vivo during CYP-induced cystitis, however, CGRP was only able to increase NR1 phosphorylation level at Ser897 but not at Ser896. It is speculated that p-NR1 Ser896 may be regulated by the PLCγ/PKC pathway (Michailidis et al., 2007; Tingley et al., 1997) that is most likely modulated by the elevated growth factors such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor in the sensory pathway during peripheral irritation (Obata and Noguchi, 2006). Phosphorylation of NR1 on Ser897 by CGRP may be mediated by Gs-coupled CGRP receptor through activation of PKA (Zou et al., 2002).

The crosstalk between the Akt pathway and the NMDAR signaling has also been suggested. However, in our study we found that cystitis- and CGRP-elicited phosphorylation of NR1 subunit at Ser897 was not regulated by the PI3K/Akt pathway. These results suggest that NMDAR activation may involve multiple signal facilitation. The regulation of the Akt activity by NMDAR is shown in either NR2B or nonNR2B - mediated survival signal in neuronal culture (Hetman and Kharebava, 2006; Perkinton et al., 2002). However, during inflammatory visceral pain state inhibition of NMDAR with MK801 was unable to block cystitis-induced Akt activity in the spinal cord even though it blocked CREB activation caused by CYP-induced cystitis or CGRP.

Visceral pain is a highly complex entity that can occur due to hyperexcitability of the primary sensory afferents and dysregulation of spinal neurons (central sensitization) that modulate nociceptive transmission. Upon visceral irritation (e.g. cystitis), hypersensitization of the primary afferent neurons leads to neurotransmitter release to the spinal cord where it can activate intracellular signaling components such as Akt and CREB. Activation of the NMDAR mediates calcium flux modifying the strength or efficacy of synaptic transmission. Increases in the intracellular calcium level also contribute to CREB activation and subsequent gene transcription thereby leading to plastic changes in sensory reflex pathway that regulate the function of the viscera. Our results demonstrate that cystitis-induced spinal plasticity involves multiple signal components that work together or independently in modulating visceral function. Therapeutic target of a single pathway is critical but is not sufficient in treatment.

Highlights.

- Cystitis increases the phosphorylation levels of Akt, NMDAR and CREB in spinal cord;

- Activation of Akt and NMDAR lead to CREB phosphorylation;

- Activation of Akt does not lead to the phosphorylation of NR1 subunit of the NMDAR;

- Activation of NMDAR does not contribute to Akt activation in the spinal cord.

Acknowledgments

SUPPORTING GRANT: NIH DK077917 (LYQ)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST: NONE

REFERENCES

- Alessi DR, Andjelkovic M, Caudwell B, Cron P, Morrice N, Cohen P, Hemmings BA. Mechanism of activation of protein kinase B by insulin and IGF-1. Embo Journal. 1996;15(23):6541–6551. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amaravadi R, Thompson CB. The survival kinases Akt and Pim as potential pharmacological targets. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2005;115(10):2618–2624. doi: 10.1172/JCI26273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson LE, Seybold VS. Phosphorylated cAMP response element binding protein increases in neurokinin-1 receptor-immunoreactive neurons in rat spinal cord in response to formalin-induced nociception. Neuroscience Letters. 2000;283(1):29–32. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(00)00908-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arms L, Vizzard MA. Role for pAKT in rat urinary bladder with cyclophosphamide (CYP)-induced cystitis. American Journal of Physiology-Renal Physiology. 2011;301(2):F252–F262. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00556.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benemei S, Nicoletti P, Capone JG, Geppetti P. CGRP receptors in the control of pain and inflammation. Current Opinion in Pharmacology. 2009;9(1):9–14. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2008.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradesi S. Role of spinal cord glia in the central processing of peripheral pain perception. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;22(5):499–511. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2010.01491.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carozzi V, Marmiroli P, Cavaletti G. Focus on the Role of Glutamate in the Pathology of the Peripheral Nervous System. Cns & Neurological Disorders-Drug Targets. 2008;7(4):348–360. doi: 10.2174/187152708786441876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Molliver DC, Gebhart GF. The P2Y2 receptor sensitizes mouse bladder sensory neurons and facilitates purinergic currents. J Neurosci. 2010;30(6):2365–2372. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5462-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi JI, Svensson CI, Koehrn FJ, Bhuskute A, Sorkin LS. Peripheral inflammation induces tumor necrosis factor dependent AMPA receptor trafficking and Akt phosphorylation in spinal cord in addition to pain behavior. Pain. 2010;149(2):243–253. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi JIL, Koehrn FJ, Sorkin LS. Carrageenan induced phosphorylation of Akt is dependent on neurokinin-1 expressing neurons in the superficial dorsal horn. Molecular Pain. 2012:8. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-8-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta SR, Brunet A, Greenberg ME. Cellular survival: a play in three Akts. Genes & Development. 1999;13(22):2905–2927. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.22.2905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Biasi S, Rustioni A. Glutamate and substance P coexist in primary afferent terminals in the superficial laminae of spinal cord. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85(20):7820–7824. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.20.7820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du KY, Montminy M. CREB is a regulatory target for the protein kinase Akt/PKB. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273(49):32377–32379. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.49.32377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duggan AW, Hendry IA, Morton CR, Hutchison WD, Zhao ZQ. CUTANEOUS STIMULI RELEASING IMMUNOREACTIVE SUBSTANCE-P IN THE DORSAL HORN OF THE CAT. Brain Research. 1988;451(1-2):261–273. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)90771-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durham PL, Masterson CG. Two mechanisms involved in trigeminal CGRP release: implications for migraine treatment. Headache. 2013;53(1):67–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2012.02262.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galeazza MT, Garry MG, Yost HJ, Strait KA, Hargreaves KM, Seybold VS. PLASTICITY IN THE SYNTHESIS AND STORAGE OF SUBSTANCE-P AND CALCITONIN-GENE-RELATED PEPTIDE IN PRIMARY AFFERENT NEURONS DURING PERIPHERAL INFLAMMATION. Neuroscience. 1995;66(2):443–458. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)00545-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao X, Kim HK, Chung JM, Chung K. Enhancement of NMDA receptor phosphorylation of the spinal dorsal horn and nucleus gracilis neurons in neuropathic rats. Pain. 2005;116(1-2):62–72. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.03.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebhart GF, Bielefeldt K, Ozaki N. Gastric hyperalgesia and changes in voltage gated sodium channel function in the rat. Gut. 2002;51:I15–I18. doi: 10.1136/gut.51.suppl_1.i15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez GA, Montminy MR. CYCLIC-AMP STIMULATES SOMATOSTATIN GENE-TRANSCRIPTION BY PHOSPHORYLATION OF CREB AT SERINE-133. Cell. 1989;59(4):675–680. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90013-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetman M, Kharebava G. Survival signaling pathways activated by NMDA receptors. Current Topics in Medicinal Chemistry. 2006;6(8):787–799. doi: 10.2174/156802606777057553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoeger-Bement MK, Sluka KA. Phosphorylation of CREB and mechanical hyperalgesia is reversed by blockade of the cAMP pathway in a time-dependent manner after repeated intramuscular acid injections. Journal of Neuroscience. 2003;23(13):5437–5445. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-13-05437.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honore P, Kamp EH, Rogers SD, Gebhart GF, Mantyh PW. Activation of lamina I spinal cord neurons that express the substance P receptor in visceral nociception and hyperalgesia. Journal of Pain. 2002;3(1):3–11. doi: 10.1054/jpai.2002.27001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji RR, Rupp F. Phosphorylation of transcription factor CREB in rat spinal cord after formalin-induced hyperalgesia: Relationship to c-fos induction. Journal of Neuroscience. 1997;17(5):1776–1785. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-05-01776.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johannessen M, Delghandi MP, Moens U. What turns CREB on? Cellular Signalling. 2004;16(11):1211–1227. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly A, Lynch MA. Long-term potentiation in dentate gyrus of the rat is inhibited by the phosphoinositide 3-kinase inhibitor, wortmannin. Neuropharmacology. 2000;39(4):643–651. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(99)00169-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingsbury TJ, Krueger BK. Ca2+, CREB and kruppel: a novel KLF7-binding element conserved in mouse and human TRKB promoters is required for CREB-dependent transcription. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2007;35(3):447–455. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohno T, Wang H, Amaya F, Brenner GJ, Cheng JK, Ji RR, Woolf CJ. Bradykinin enhances AMPA and NMDA receptor activity in spinal cord dorsal horn neurons by activating multiple kinases to produce pain hypersensitivity. J Neurosci. 2008;28(17):4533–4540. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5349-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovelowski CJ, Ossipov MH, Sun H, Lai J, Malan TP, Porreca F. Supraspinal cholecystokinin may drive tonic descending facilitation mechanisms to maintain neuropathic pain in the rat. Pain. 2000;87(3):265–273. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00290-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landau AM, Yashpal K, Cahill CM, St Louis M, Ribeiro-Da-Silvade A, Henry JL. Sensory neuron and substance P involvement in symptoms of a zymosan-induced rat model of acute bowel inflammation. Neuroscience. 2007;145(2):699–707. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.11.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F, Tsien JZ. Memory and the NMDA receptors. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(3):302–303. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcibr0902052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin CH, Yeh SH, Lu KT, Leu TH, Chang WC, Gean PW. A role for the PI-3 kinase signaling pathway in fear conditioning and synaptic plasticity in the amygdala. Neuron. 2001;31(5):841–851. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00433-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonze BE, Ginty DD. Function and regulation of CREB family transcription factors in the nervous system. Neuron. 2002;35(4):605–623. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00828-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma W, Quirion R. Increased phosphorylation of cyclic AMP response element-binding protein (CREB) in the superficial dorsal horn neurons following partial sciatic nerve ligation. Pain. 2001;93(3):295–301. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00335-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Man HY, Wang Q, Lu WY, Ju W, Ahmadian G, Liu L, D'Souza S, Wong TP, Taghibiglou C, Lu J, Becker LE, Pei L, Liu F, Wymann MP, MacDonald JF, Wang YT. Activation of PI3-kinase is required for AMPA receptor insertion during LTP of mEPSCs in cultured hippocampal neurons. Neuron. 2003;38(4):611–624. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00228-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning BD, Cantley LC. AKT/PKB signaling: navigating downstream. Cell. 2007;129(7):1261–1274. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masu M, Nakajima Y, Moriyoshi K, Ishii T, Akazawa C, Nakanashi S. Molecular characterization of NMDA and metabotropic glutamate receptors. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1993;707:153–164. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb38050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng JH, Ovsepian SV, Wang JF, Pickering M, Sasse A, Aoki KR, Lawrence GW, Dolly JO. Activation of TRPV1 Mediates Calcitonin Gene-Related Peptide Release, Which Excites Trigeminal Sensory Neurons and Is Attenuated by a Retargeted Botulinum Toxin with Anti-Nociceptive Potential. Journal of Neuroscience. 2009;29(15):4981–4992. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5490-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messersmith DJ, Kim DJ, Iadarola MJ. Transcription factor regulation of prodynorphin gene expression following rat hindpaw inflammation. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1998;53(1-2):260–269. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(97)00308-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michailidis IE, Helton TD, Petrou VI, Mirshahi T, Ehlers MD, Logothetis DE. Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate regulates NMDA receptor activity through alpha-actinin. J Neurosci. 2007;27(20):5523–5532. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4378-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miletic G, Pankratz MT, Miletic V. Increases in the phosphorylation of cyclic AMP response element binding protein (CREB) and decreases in the content of calcineurin accompany thermal hyperalgesia following chronic constriction injury in rats. Pain. 2002;99(3):493–500. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(02)00242-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori H, Mishina M. Structure and function of the NMDA receptor channel. Neuropharmacology. 1995;34(10):1219–1237. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(95)00109-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morton CR, Hutchison WD. Release of sensory neuropeptides in the spinal cord: studies with calcitonin gene-related peptide and galanin. Neuroscience. 1989;31(3):807–815. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(89)90443-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obata K, Noguchi K. BDNF in sensory neurons and chronic pain. Neurosci Res. 2006;55(1):1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okajima K, Harada N. Regulation of inflammatory responses by sensory neurons: molecular mechanism(s) and possible therapeutic applications. Curr Med Chem. 2006;13(19):2241–2251. doi: 10.2174/092986706777935131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkinton MS, Ip JK, Wood GL, Crossthwaite AJ, Williams RJ. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase is a central mediator of NMDA receptor signalling to MAP kinase (Erk1/2), Akt/PKB and CREB in striatal neurones. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2002;80(2):239–254. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-3042.2001.00699.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pezet S, Marchand F, D'Mello R, Grist J, Clark AK, Malcangio M, Dickenson AH, Williams RJ, McMahon SB. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase is a key mediator of central sensitization in painful inflammatory conditions. J Neurosci. 2008;28(16):4261–4270. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5392-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao LY, Grider JR. Up-regulation of calcitonin gene-related peptide and receptor tyrosine kinase TrkB in rat bladder afferent neurons following TNBS colitis. Exp Neurol. 2007;204(2):667–679. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.12.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao LY, Grider JR. Colitis induces calcitonin gene-related peptide expression and Akt activation in rat primary afferent pathways. Exp Neurol. 2009;219(1):93–103. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.04.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin N, Neeper MP, Liu Y, Hutchinson TL, Lubin ML, Flores CM. TRPV2 is activated by cannabidiol and mediates CGRP release in cultured rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. Journal of Neuroscience. 2008;28(24):6231–6238. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0504-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero A, Romero-Alejo E, Vasconcelos N, Puig MM. Glial cell activation in the spinal cord and dorsal root ganglia induced by surgery in mice. Eur J Pharmacol. 2013;702(1-3):126–134. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2013.01.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafers M, Sorkin L. Effect of cytokines on neuronal excitability. Neuroscience Letters. 2008;437(3):188–193. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.03.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweitzer ES, Jeng CJ, TaoCheng JH. Selective localization and regulated release of calcitonin gene-related peptide from dense-core vesicles in engineered PC12 cells. Journal of Neuroscience Research. 1996;46(5):519–530. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19961201)46:5<519::AID-JNR1>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seybold VS. The role of peptides in central sensitization. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2009;(194):451–491. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-79090-7_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seybold VS, McCarson KE, Mermelstein PG, Groth RD, Abrahams LG. Calcitonin gene-related peptide regulates expression of neurokinin1 receptors by rat spinal neurons. J Neurosci. 2003;23(5):1816–1824. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-05-01816.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun P, Enslen H, Myung PS, Maurer RA. Differential activation of CREB by Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinases type II and type IV involves phosphorylation of a site that negatively regulates activity. Genes Dev. 1994;8(21):2527–2539. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.21.2527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun RQ, Tu YJ, Yan JY, Willis WD. Activation of protein kinase B/Akt signaling pathway contributes to mechanical hypersensitivity induced by capsaicin. Pain. 2006;120(1-2):86–96. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki R, Rahman W, Rygh LJ, Webber M, Hunt SP, Dickenson AH. Spinal-supraspinal serotonergic circuits regulating neuropathic pain and its treatment with gabapentin. Pain. 2005;117(3):292–303. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taves S, Berta T, Chen G, Ji RR. Microglia and spinal cord synaptic plasticity in persistent pain. Neural Plasticity Volume. 2013;2013:p10. doi: 10.1155/2013/753656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tingley WG, Ehlers MD, Kameyama K, Doherty C, Ptak JB, Riley CT, Huganir RL. Characterization of protein kinase A and protein kinase C phosphorylation of the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor NR1 subunit using phosphorylation site-specific antibodies. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(8):5157–5166. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.8.5157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toker A, Newton AC. Cellular signaling: pivoting around PDK-1. Cell. 2000;103(2):185–188. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00110-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Heide LP, Kamal A, Artola A, Gispen WH, Ramakers GM. Insulin modulates hippocampal activity-dependent synaptic plasticity in a N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor and phosphatidyl-inositol-3-kinase-dependent manner. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2005;94(4):1158–1166. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vizzard MA. Alterations in neuropeptide expression in lumbosacral bladder pathways following chronic cystitis. Journal of Chemical Neuroanatomy. 2001;21(2):125–138. doi: 10.1016/s0891-0618(00)00115-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu JT, Tu HY, Xin WJ, Liu XG, Zhang GH, Zhai CH. Activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and protein kinase B/Akt in dorsal root ganglia and spinal cord contributes to the neuropathic pain induced by spinal nerve ligation in rats. Exp Neurol. 2007;206(2):269–279. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Q, Fitzsimmons B, Steinauer J, O'Neill A, Newton AC, Hua XY, Yaksh TL. Spinal phosphinositide 3-kinase-Akt-mammalian target of rapamycin signaling cascades in inflammation-induced hyperalgesia. J Neurosci. 2011;31(6):2113–2124. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2139-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu ZZ, Zhang L, Liu T, Park JY, Berta T, Yang R, Serhan CN, Ji RR. Resolvins RvE1 and RvD1 attenuate inflammatory pain via central and peripheral actions. Nat Med. 2010;16(5):592–597. doi: 10.1038/nm.2123. 591p following 597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu SJ, Xia CM, Kay JC, Qiao LY. Activation of extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase 5 is essential for cystitis- and nerve growth factor-induced calcitonin gene-related peptide expression in sensory neurons. Molecular Pain. 2012:8. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-8-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Odom DT, Koo SH, Conkright MD, Canettieri G, Best J, Chen H, Jenner R, Herbolsheimer E, Jacobsen E, Kadam S, Ecker JR, Emerson B, Hogenesch JB, Unterman T, Young RA, Montminy M. Genome-wide analysis of cAMP-response element binding protein occupancy, phosphorylation, and target gene activation in human tissues. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(12):4459–4464. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501076102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu W, Oxford GS. Phosphoinositide-3-kinase and mitogen activated protein kinase signaling pathways mediate acute NGF sensitization of TRPV1. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2007;34(4):689–700. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2007.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou X, Lin Q, Willis WD. Enhanced phosphorylation of NMDA receptor 1 subunits in spinal cord dorsal horn and spinothalamic tract neurons after intradermal injection of capsaicin in rats. J Neurosci. 2000;20(18):6989–6997. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-18-06989.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou X, Lin Q, Willis WD. Role of protein kinase A in phosphorylation of NMDA receptor 1 subunits in dorsal horn and spinothalamic tract neurons after intradermal injection of capsaicin in rats. Neuroscience. 2002;115(3):775–786. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00490-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]