Summary

The histone H2A-H2B heterodimer is an integral component of the nucleosome. The cellular localization and deposition of H2A-H2B into chromatin is regulated by numerous factors including histone chaperones such as Nucleosome Assembly Protein 1 (Nap1). We use hydrogen-deuterium exchange coupled to mass spectrometry to characterize H2A-H2B and Nap1. Unexpectedly, we find that at low ionic strength the α-helices in H2A-H2B are frequently sampling partially disordered conformations, and that binding to Nap1 reduces this conformational sampling. We identify the interaction surface between H2A-H2B and Nap1, and confirm its relevance both in vitro and in vivo. We show that two copies of H2A-H2B bound to a Nap1 homodimer form a tetramer with contacts between H2B chains similar to those in the four-helix bundle structural motif. The organization of the complex reveals that Nap1 competes with histone-DNA and inter-histone interactions observed in the nucleosome, thereby regulating the availability of histones for chromatin assembly.

Introduction

The repeating unit of chromatin is the nucleosome, which consists of a histone octamer wrapped by 147 base pairs of DNA (Luger et al., 1997). The canonical histone octamer is composed of two copies each of H2A, H2B, H3 and H4. These histones form structurally similar H2A-H2B and H3-H4 heterodimers through head-to-tail stacking of their histone folds. A single histone fold is defined by two loops (L1 and L2) that separate three α-helices (α1, α2 and α3). Head-to-tail stacking of two histone fold domains creates an axis of pseudo-symmetry, with each end of the heterodimer pairing the L1 and L2 loops from different histone chains. In the nucleosome, these loops interact with the phosphodiester backbone of DNA (Luger and Richmond, 1998). Other critical contacts in the nucleosome occur between histone heterodimers, and primarily involve the formation of four-helix bundles (Luger et al., 1997). These bundles contain two pairs of roughly parallel helices that symmetrically pack against each other (Kamtekar and Hecht, 1995). Two separate histone heterodimers contribute to a pair, with the α3 helix from one histone being parallel to the α2 helix from another. In the nucleosome, two copies of H3-H4 form a tetramer via a four-helix bundle between the two H3 chains, while H2A-H2B binds on either side via a four-helix bundle between H2B and H4. H2A is the only core histone that is not directly involved in a four-helix bundle in the nucleosome.

The histone-DNA and inter-histone contacts in the nucleosome dictate the equilibrium between chromatin assembly and disassembly. A key component of this equilibrium is the availability of non-nucleosomal histones. While a small portion of the pool of histones may be free or unbound, the majority is thought to be bound by histone chaperones (De Koning et al., 2007; Elsasser and D’Arcy, 2012). Histone chaperones are histone-binding proteins that by definition influence nucleosome formation in vitro in an ATP-independent fashion (Elsasser and D’Arcy, 2012). The mechanism of histone ‘chaperoning’ however is poorly understood. It is not known how histone chaperones impact histones to either prevent their incorporation into nonfunctional complexes (Andrews et al., 2010), or promote their deposition to form functional nucleosomes. Hints have come from structural studies of histone chaperones bound by their cognate histones. These reveal that although histone chaperones are structurally diverse, a recurrent theme is their ability to block histone interfaces required for nucleosome formation (Cho and Harrison, 2011; Elsasser et al., 2012; English et al., 2006; Hondele et al., 2013; Hu et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2012; Zhou et al., 2008; Zhou et al., 2011). This has been observed for many chaperones, but is yet to be shown for chaperone Nucleosome Assembly Protein 1 (Nap1).

The unknown mechanistic basis of histone chaperoning prompted us to characterize H2A-H2B alone and in complex with Nap1. Nap1 is a homodimeric histone chaperone that binds H2A-H2B with nanomolar affinity (Andrews et al., 2008; Park and Luger, 2006). We employed hydrogen/deuterium exchange (H/DX) coupled to high resolution mass spectrometry, which examines protein structure, dynamics and interfaces in solution (Englander, 2006; Hoofnagle et al., 2003). H/DX measures the rate at which amide hydrogens in a protein backbone exchange for deuterons from the solvent. The rate of exchange is reduced by H-bonds made by the protein backbone, such as those associated with α-helices, β-sheets or protein-protein interfaces. Nap1 and H2A-H2B are candidates for H/DX as their structures have been solved allowing interpretation of the H/DX data in a structural context. Nap1 has been solved on its own, while H2A-H2B has been solved in the context of the nucleosome (Park and Luger, 2006; White et al., 2001).

Based on H/DX and a number of complementary experiments, we show that H2A-H2B free in solution is frequently sampling partially disordered conformations, and that Nap1 reduces this conformational flexibility. We define the molecular arrangement of the complex between H2A-H2B and Nap1, including identification of the Nap1 and H2A-H2B residues that are likely to be involved in the interaction. We show that H2A-H2B bound to Nap1 can form a tetramer mediated by interactions between multiple copies of H2B. These interactions are similar to those in the four-helix bundle structural motif observed between histones in the nucleosome. The organization of the complex allows Nap1 to directly compete H2A-H2B from DNA, and to occlude H2A-H2B interfaces required for nucleosome formation. Our findings introduce a new feature of H2A-H2B that has ramifications for histone chaperone mechanism, and reveal the molecular arrangement of the complex between H2A-H2B and Nap1.

Results

Nap1 adopts a well-folded conformation in solution

We first performed H/DX of Nap1 and H2A-H2B separately at 60 mM NaCl. We conducted a time course of exchange that was initiated by diluting a concentrated recombinant protein stock with deuterium. Exchange was quenched after 10, 102, 103 or 104 seconds by reducing the pH and temperature. The proteins were then digested with Pepsin and the masses of resultant peptides determined using high resolution LC-MS. Digestion produced 204 Nap1 peptides and 103 H2A-H2B peptides. The sequence coverage of Nap1 and H2A-H2B is high (85%), although no peptides were recovered for the acidic region of the C-terminal tail of Nap1, or the basic N-terminal tail of H2B. The % D was calculated for each peptide from the overall centroid of the isotopic envelope assigned using ExMS (Kan et al., 2011) (See Supplemental Experimental Procedures). The data are visualized using heat maps where the peptides are aligned against a schematic of the secondary structures observed in Nap1 alone (PDB 2Z2R) or H2A-H2B in the nucleosome (PDB 1ID3).

H/DX of Nap1 at 60 mM NaCl correlates well with the crystal structure of Nap1 (Figure S1A). Flexible regions that are either not visible in the structure, or have high vibrational motion or B-factors, or are stabilized by contacts in the crystal lattice, exchange rapidly and reach 75–100% D in only 10 seconds (Figure 1A). These flexible regions include the N- and C-terminal tails, the accessory domain (α3 and adjacent loop region), the β-hairpin (β5-β6) and several long loops (β3-β4 loop, α6-α7 loop). Conversely, well-structured regions of Nap1 with extensive H-bonding networks, exchange several orders of magnitude slower, reaching 75–100% D after 103 seconds (Figure S1B). These structured regions include the dimerization helix (α2), the earmuff domain (α4-β4) and the helical ‘underside’ (α7-α8). H/DX thus suggests that the different Nap1 sub-domains have variable degrees of H-bonding in solution.

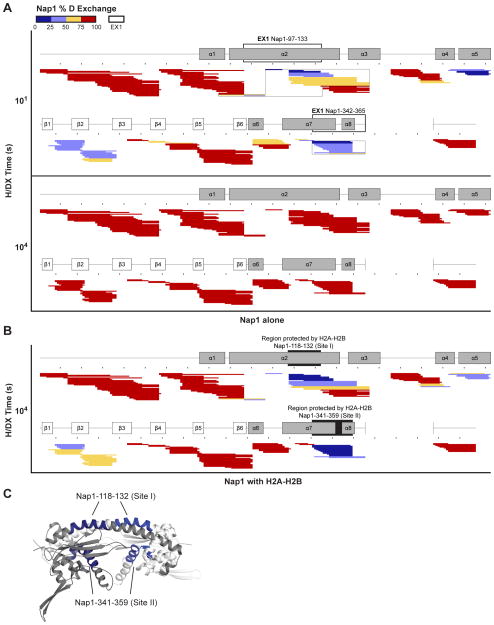

Figure 1. H/DX of Nap1 in the absence and presence of H2A-H2B.

(A–B) Heat maps of Nap1 at 10 and 104 seconds H/DX (A) and Nap1 with an equimolar amount of H2A-H2B at 104 seconds H/DX (B). Each peptide is represented by a rectangle that is colored according to % D exchange and aligned against a schematic of Nap1 secondary structure (PDB 2Z2R). Taller rectangles indicate multiple charged states of the same peptide and black dots denote every 10th residue. Nap1 regions with EX1, and regions protected by H2A-H2B (Site I and II) are boxed by clear or filled rectangles respectively. Complete time courses of Nap1 H/DX, fold-changes in % D with and without H2A-H2B, and example peptides are shown in Figure S1. (C) Structure of the Nap1 homodimer (PDB 2Z2R; Chain A is gray and Chain B is white) showing regions protected by H2A-H2B (Site I and II are blue).

The H2A-H2B heterodimer samples partially unfolded conformations in solution

Unlike Nap1, H/DX of H2A-H2B in solution at 60 mM NaCl does not correlate well with the crystal structure of H2A-H2B in the nucleosome (Figure 2). We expected the helical histone fold regions of H2A-H2B to be substantially protected from exchange when compared to the unstructured tail regions that are not visible in the crystal structure. Instead, we observe that that both the helical histone fold and unstructured tail regions exchange rapidly, with all of H2A and most of H2B reaching 75–100% D in only 10 seconds (Figure 2, left). This rapid rate of exchange is similar to that observed for intrinsically disordered proteins such as MeCP2 (Hansen et al., 2011). Intrinsically disordered proteins contain few H-bonds as they lack stable secondary and tertiary structure. The fast exchange is repeatable (Figure 3A–B) and is not due to poorly prepared H2A-H2B. Our H2A-H2B is helical at the high concentrations used for circular dichroism (Figure 3C) and functions in nucleosome reconstitution and Nap1-binding assays (see below).

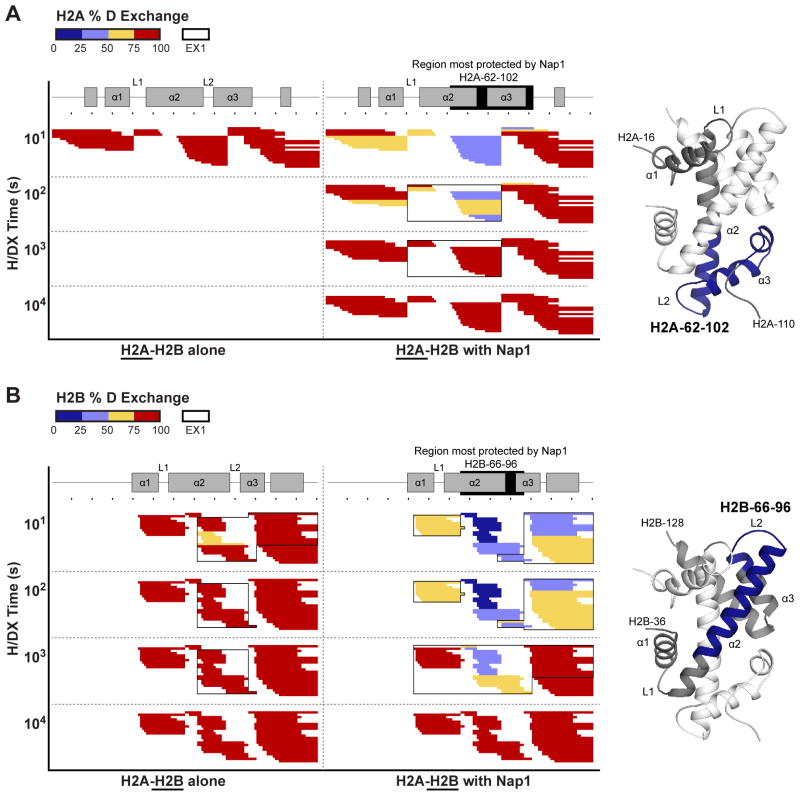

Figure 2. H/DX of H2A-H2B in the absence and presence of Nap1.

(A–B) Heat maps of H/DX time course of H2A (A) and H2B (B) in the absence and presence of an equimolar amount of Nap1. Formatting is as described for Figure 1 with the peptides aligned against a schematic of H2A-H2B secondary structure (PDB 1ID3). H2A-H2B regions with EX1 and most-protected by Nap1 are boxed by clear or filled rectangles respectively. The underlined protein is shown in the panel. Heat maps for H2A at 102–104 seconds are not shown as complete exchange is reached after 10 seconds. Fold-changes in % D with and without Nap1, and example peptides are shown in Figure S2. Adjacent to the heat maps are structures of H2A-H2B as observed in the yeast nucleosome structure (PDB 1ID3) showing regions most-protected by Nap1 (blue). In (A), H2A is gray and H2B is white. In (B), H2A is white and H2B is gray. H2A-H2B is shown in the same orientation in both images. Terminal residues, secondary structures and regions most-protected by Nap1 are labeled.

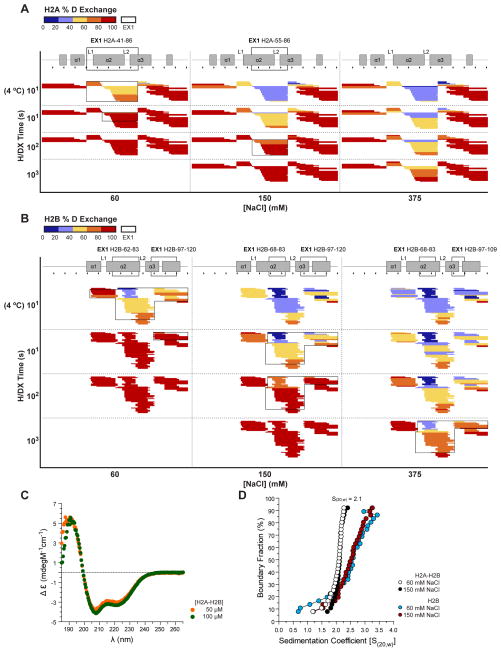

Figure 3. H/DX of H2A-H2B is salt-dependent.

(A–B) Heat maps of H/DX time course of H2A (A) and H2B (B) at 60, 150 and 375 mM NaCl. Formatting is as described for Figure 2. Heat maps at 103 seconds are not shown for 60 mM NaCl as complete exchange is reached after 102 seconds. An alternative representation of the same data is shown in Figure S3A–C. Subtle variances between the 60 mM NaCl data shown here compared to Figure 2 are due to differing conditions, particularly laboratory room temperature and Pepsin column, under which repeats were performed. (C) Circular dichroism spectra of 50 (orange) or 100 (green) μM H2A-H2B at 60 mM NaCl. (D) Sedimentation velocity analysis of H2A-H2B and H2B alone at micromolar protein concentration with 60 (white or blue) or 150 (black or red) mM NaCl.

To further investigate the surprisingly rapid exchange of H2A-H2B at 60 mM NaCl, we performed H/DX of H2A-H2B at 150 and 375 mM NaCl (Figure 3A–B, S3A–B). We included an additional 10 second time point at 4 °C, for which the chemical H/DX rate is equivalent to 1 second at room temperature (Englander, 2006). We anticipated that salt would influence the H/DX rate of H2A-H2B as histone proteins can be refolded and reconstituted into nucleosomes in a salt-dependent manner in vitro (Dyer et al., 2004). Throughout our H/DX time course we observe that almost all H2A-H2B peptides have a reduction in % D as NaCl is increased (Figure 3A–B, S3A–B). Decreased exchange at higher NaCl is also indicated by the time taken for all peptides to reach 81–100% D; at 150 mM and 375 mM it takes ≥103 seconds, while at 60 mM NaCl it takes only 10 seconds. The rate of H2A-H2B exchange is thus dependent on the concentration of NaCl. The slower exchange observed at 4 °C and/or higher NaCl also correlates with nucleosomal H2A-H2B secondary structure (Figure S3C), showing that ionic strength enhances H-bond formation by main chain atoms of H2A-H2B.

A possible explanation for rapid exchange of H2A-H2B at 60 mM NaCl is dissociation of the heterodimer. To test this, we performed sedimentation velocity analysis at micromolar protein concentration with 60 or 150 mM NaCl, similar to the conditions used for H/DX. Such analysis returns a midpoint S20,w of 2.1 S for H2A-H2B at both salt concentrations (Figure 3D). This value represents a H2A-H2B heterodimer with a frictional coefficient of 1.6 (Ultrascan Version 9.9). It cannot represent H2A or H2B alone as the frictional co-efficient would have to be near to 1.0 (Ultrascan Version 9.9). A frictional coefficient near to 1.0 suggests a globular or spherical protein shape that is unlikely given that monomeric H2A and H2B are unfolded and/or contain unstructured tails (Arnan et al., 2003; Banks and Gloss, 2003; D’Anna and Isenberg, 1974; Karantza et al., 1995). Under exchange conditions, H2A-H2B also has a distinct sedimentation profile from either H2A alone or H2B alone (Figure 3D and data not shown). Fast exchange of H2A-H2B is thus not due to dissociation of the H2A-H2B heterodimer. A reasonable explanation for rapid exchange of H2A-H2B at low salt is the sampling of partially unfolded states. In these states, the H-bonds in H2A-H2B helices would be transiently broken, allowing the amide hydrogens to exchange rapidly with deuterons from the solvent.

Regions of Nap1 and H2A-H2B cooperatively unfold

H/DX of Nap1 and H2A-H2B separately also identifies protein regions with exchange kinetics indicative of cooperative unfolding (Figure 1, 2 and S3D). This kinetics is described as EX1 (opposed to the standard EX2) and occurs when the rate of secondary structure refolding is slower than the rate of chemical exchange, causing multiple hydrogens to exchange simultaneously (Englander, 2006; Hoofnagle et al., 2003). EX1 is manifested as a multi-modal distribution of isotopic peaks (EX2 has a single distribution of isotopic peaks). For example, if there is slow unfolding and refolding, one will observe an un-exchanged peptide population and a separate fully-exchanged peptide population. A multi-modal distribution of isotopic peaks is observed for Nap1 amino acids 97–133, 194–211 and 342–365; H2A amino acids 55–86; and H2B amino acids 68–83 and 97–120 (Figure 1–3). For H2A-H2B, these regions display EX1 at the near physiological salt concentration of 150 mM NaCl. In both Nap1 and H2A-H2B, these regions localize at interfaces between α-helices. We determined the number of residues contributing to EX1, which reveals that large regions, particularly of H2B, are cooperatively unfolding (Figure S3E). The detection of EX1 is notable as it is presumed rare under native conditions, although it has been observed for a portion of (H3-H4)2 (Black et al., 2004). It may be a feature of helical regions of dimeric proteins.

H2A-H2B alters H/DX of two sites in Nap1

We next performed H/DX of Nap1 in the presence of an equimolar amount of H2A-H2B at 60 mM NaCl (Figure 1B, S1C–E). Low salt was chosen to promote the interaction between Nap1 and H2A-H2B (Park and Luger, 2006). Comparing H/DX of Nap1 alone and H2A-H2B•Nap1 allows identification of regions of Nap1 that are protected from exchange by H2A-H2B. The 104 second time point, shown in Figure 1B, is particularly demonstrative as Nap1 alone has fully exchanged (Figure 1A bottom versus 1B). This comparison identifies Nap1 amino acids 118–132 (hereafter, Site I) and Nap1 amino acids 341–359 (hereafter, Site II) as the regions most protected by H2A-H2B. After 104 seconds H/DX, these sites have less than 25% D exchange. Based on representative peptides, this corresponds to protection of 13 and 12 residues at each site respectively (Figure S1E). These sites also have the greatest fold change in % D with and without H2A-H2B (> 4.0-fold) after 10, 102, 103 and 104 seconds exchange (Figure S1D). We further note that H2A-H2B inhibits Nap1 EX1, with Site I and Site II both being in regions that cooperatively unfolded in Nap1 alone. Binding of H2A-H2B thus seems to stabilize Nap1 helices. Site I is within the dimerization helix (α2), while Site II is part of the helical ‘underside’ (α7-α8) (Figure 1C).

The helical ‘underside’ of Nap1 directly binds H2A-H2B

H/DX protection of Nap1 at Site I and Site II indicates increased H-bonding of Nap1 backbone atoms at these sites in the presence of H2A-H2B. These H-bonds may constitute the H2A-H2B•Nap1 interface, or may form due to a H2A-H2B-induced conformational change. To differentiate between these two possibilities and to identify side-chains involved in Nap1 histone-binding, we performed extensive mutagenesis of Nap1 (Figure S4A). We constructed 16 Nap1 mutants each with multiple substitutions covering almost all exposed residues within the folded domain of Nap1 (Figure S1A); mutants 1–5 are in α2 (Site I), mutants 6–13 are in α3-α6 (neither Site I nor II) and mutants 14–16 are in α7-α8 (Site II). Mutants 6–13 are essentially negative controls that ensure no binding regions were missed in the H/DX. Residues were mutated to alanine, serine or glycine, and all mutants were expressed in bacteria and purified similar to wild type. Bioinformatics analyses using program SDM predicts that all mutants will maintain structural integrity (Worth et al., 2011).

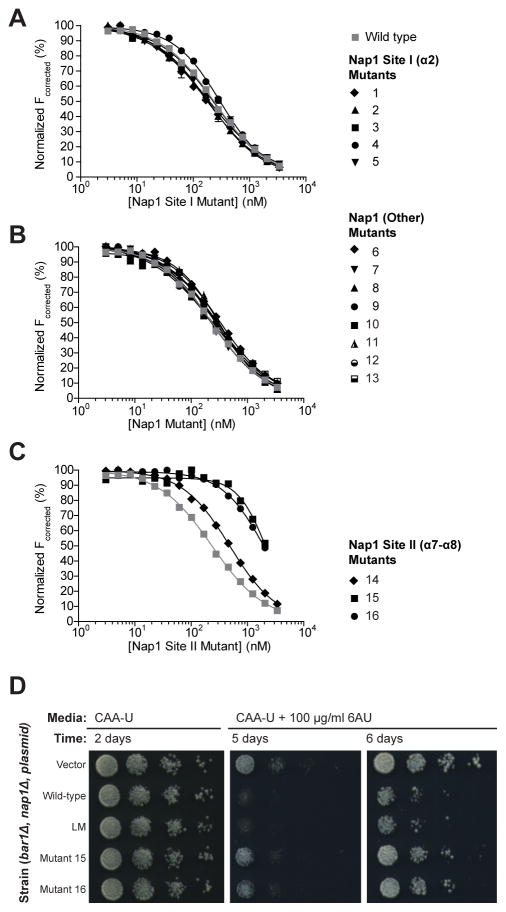

H2A-H2B-binding of each Nap1 mutant was compared to wild type Nap1 using a Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) competition assay. FRET between Alexa 488-labeled (488) H2A-H2BT118C and excess Atto 647N-labeled (647N) Nap1 was competed with unlabeled wild type or mutant Nap1 (Hieb et al., 2012). In this assay, mutants 1–13 compete similar to wild type, while mutants 14–16 have a compromised ability to compete (Figure 4A–C, black versus gray). This is demonstrated by the superposition of sigmoid competition curves for mutants 1–13 and wild type, while for mutants 14–16 the competition curves are shifted to the right of wild type. These data suggest that mutants 14–16 have compromised interaction with H2A-H2B. We confirmed the compromised H2A-H2B-binding of mutants 15 and 16 with direct affinity measurements (Figure S4B). The affinities obtained show that the interaction between H2A-H2B and mutant 15 or 16 is > 60-fold weaker than that with wild type (Table S1). Hence, the competition and affinity data shows that mutagenesis of Site II, but not Site I, compromises the ability of Nap1 to bind histones. This suggests that Nap1 binds histones through α7-α8 (Site II) and not through α2 (Site I).

Figure 4. Nap1 α7-α8 (Site II) is required for Nap1 function in vitro and in vivo.

(A–C) FRET between 10 nM 488H2A-H2BT118C and 50 nM 647NNap1 is competed with unlabeled Nap1. Unlabeled Nap1 is either wild type (gray squares) or contains mutations in Site I (A), Site II (C), or elsewhere in the protein (B). The wild type control is shown on all graphs. Each curve is representative of at least two independent experiments and each data point is the mean of duplicate measurements within a replicate. Errors bars are plus/minus one standard error of the mean and in most cases are too small to be visible. All fits have R2 ≥ 0.99. The list of mutants is shown in Figure S4A. Kd measurements, native-PAGE assays and mutant locations for Nap1 wild type, mutant 15 and mutant 16 are shown in Figure S4B–D. (D) Spots of serially diluted yeast strain BY4741 Bar1Δ Nap1Δ transformed with empty vector, or vector containing wild type, labeling mutant (LM), mutant 15 or mutant 16 Nap1. The media is CAA-U or CAA-U with 100 μg/ml 6-azauracil (6-AU) and the plates were incubated for 2–6 days. A western blot assaying expression levels of Nap1 proteins is shown in Figure S4E.

Although Site II mutants of Nap1 have a drastically weaker interaction with H2A-H2B, they still retain a nanomolar binding affinity (Table S1). In fact, in a qualitative native-PAGE assay performed at micromolar protein concentrations, mutants 15 and 16 behave similar to wild type (Figure S4C). Titration of 488H2A-H2BT118C slows the migration of mutants 15 and 16 to the same extent as it does for wild type. A similar result is obtained if mutants 15 and 16 are combined in a single protein (data not shown). The inability to abolish the Nap1 interaction with H2A-H2B is unexpected given the nature of the substitutions. Mutant 15 has seven alanine mutations that replace two negative and three positive side chains, while mutant 16 has two alanine mutations designed to locally destabilize the hydrophobic packing between α7 and α8 (Figure S4D). One interpretation is that Nap1 recognition of H2A-H2B involves a significant number of main chain atoms. This is consistent with the low sequence conservation of the identified H2A-H2B-binding site of Nap1 (Park and Luger, 2006).

We next tested whether weakening the site on Nap1 (Site II) affected Nap1 function in yeast. We examined the ability of Nap1 expressed from a vector to rescue a Nap1-deletion strain grown in the presence of 6-azauracil (6-AU). 6-AU is widely used to identify proteins involved in transcription elongation, and a role for Nap1 in transcription has recently been reported (Hampsey, 1997; Xue et al., 2013). For the Nap1-deletion strain, rescue manifests as increased sensitivity to 6-AU when compared to a vector only control (Figure 4D). As all of our recombinant Nap1 proteins were made in the background of a Nap1 labeling mutant (C200A, C249A, C272A), we assayed this mutant in addition to Nap1 mutants 15 and 16. Western blotting of cell lysates confirmed expression of all mutants, with mutant 16 being expressed slightly less than the others (Figure S4E). Mutant Nap1 expression also has no effect on yeast growth in the absence of 6-AU (Figure 4D, left). We observe that the labeling mutant can completely rescue the Nap1-deletion strain, while mutants 15 and 16 cannot (Figure 4D, right). In the presence of 6-AU, the labeling mutant grows similar to wild type, while mutants 15 and 16 resemble the vector only control. This indicates a loss-of-function phenotype for mutants 15 and 16 in vivo, which correlates with a weakened H2A-H2B affinity in vitro.

Nap1 stabilizes the histone fold domains of H2A-H2B

The aforementioned H/DX experiment with equimolar amounts of Nap1 and H2A-H2B can also be analyzed from the H2A-H2B perspective. We can compare H/DX of H2A-H2B alone to that of H2A-H2B•Nap1 to identify regions of H2A-H2B protected from exchange by Nap1 (Figure 2, left versus right panel). This comparison reveals that Nap1 causes most of H2A-H2B to exchange several orders of magnitude slower. The key observation is that Nap1 slows exchange of peptides from the entire histone fold domains (α1-α3) of H2A and H2B, albeit to different extents. At 10 seconds H/DX, the fold change in % D with and without Nap1 ranges from 1.4 to > 3.5 (Figure S2). This shows that Nap1 induces a global stabilization of the H2A-H2B histone fold domains, transforming them from the previously described partially disordered state to a folded conformation. Interestingly, interaction with Nap1 does not change which regions of H2A-H2B exhibit EX1 kinetics. This means that H2A-H2B is still able to cooperatively unfold in the presence of Nap1.

The most protected regions of H2A-H2B are of particular interest as putative interaction sites for Nap1. In the presence of Nap1, the most protected region of H2A spans amino acids 62–102, while the most protected region of H2B spans amino acids 66–96 (Figure 2). After 10 seconds H/DX, these sites have less than 50% D exchange. These regions have the greatest fold change in % D with and without Nap1 at 10, 102 and 103 seconds, with protection of H2B amino acids 66–96 being greater than that of H2A amino acids 62–102 (Figure S2). In determining the most protected regions of H2A-H2B, we chose a cut-off fold change of > 2.0-fold for H2A and > 2.5-fold for H2B, although most H2B peptides in this region have a fold change much greater than 2.5. Reducing the cut-off fold change to > 2.0-fold for H2B simply extends the protected region in a C-terminal direction (Figure S2C, green peptides). Mapping the most protected regions onto H2A-H2B reveals them to encompass the L2 loop and adjacent α2 and α3 regions of both H2A and H2B. Given the head-to-tail stacking of H2A and H2B, these regions are located at opposite ends of the H2A-H2B heterodimer (Figure 2).

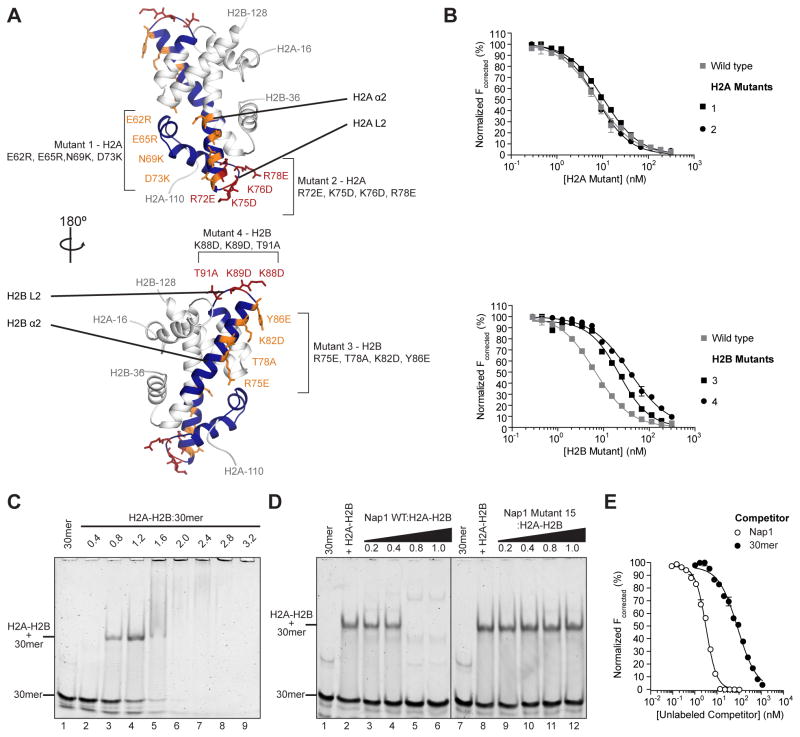

Nap1 directly binds H2B

H/DX protection at H2A amino acids 62–102 and H2B amino acids 66–96 may be due to direct interaction with Nap1 or a Nap1-induced conformational change. To distinguish between these options, we made two pairs of mutants in H2A and H2B with matched locations in the pseudo-symmetric H2A-H2B heterodimer (Figure 5A). These mutants are located in α2 (mutants 1 and 3) or the L2 loop (mutants 2 and 4) and reverse charged side chains. All mutants formed H2A-H2B heterodimers similar to their wild type counterparts. The Nap1-binding of each mutant was compared to wild type H2A-H2B by modifying the FRET competition assay described above. FRET between excess 488H2A-H2BT118C and 647NNap1 was competed with unlabeled wild type or mutant H2A-H2B. The assay reveals that both H2A mutants compete similar to wild type, while both H2B mutants have a compromised ability to compete (Figure 5B, black versus grey). This is demonstrated by the superposition of sigmoid competition curves for H2A mutants and wild type, while for both H2B mutants the competition curves are shifted to the right of wild type. The observed right-shift is reproducibly greater for the H2B L2 loop mutant than the α2 mutant (Table S1). The reduced competitive ability of the H2B mutants compared to the H2A mutants and wild type reflects a weaker affinity for Nap1. These data suggest that H2A-H2B protection at H2B amino acids 66–96 can be attributed to direct contact with Nap1, and indicate an importance of the H2B L2 loop in Nap1 recognition. The L2 loops of both H2A and H2B interact with DNA in the nucleosome (Luger et al., 1997).

Figure 5. Nap1 directly contacts H2B and prevents H2A-H2B from binding DNA.

(A) Structures of a H2A-H2B (PDB 1ID3) showing the location of mutants in the α2 (orangesticks) or L2 loop (red sticks) of H2A (top) and H2B (bottom) in the context of the H2A-H2B regions most-protected by Nap1 (blue). (B) FRET between 10 nM 488H2A-H2BT118C and 1 nM 647NNap1 is competed with unlabeled H2A-H2B. Unlabeled H2A-H2B is either wild type (gray squares) or contains mutations in H2A (top) or H2B (bottom). (C) Native-PAGE assay of H2A-H2B•30mer where 0–1.6 μM H2A-H2B is titrated against 0.5 μM 30mer. (D) Native-PAGE competition assay where 0–0.5 μM wild type (WT; left) or mutant 15 (right) Nap1 is titrated against 0.5 μM H2A-H2B•30mer. For (C–D), samples were separated by 5% native-PAGE and the DNA visualized with SYBR Gold (Ex. 488 nm, Em. 520 nm). (E) FRET between 5 nM 488H2A-H2BT112C and 50 nM 647N30mer is competed with unlabeled Nap1 wild type (open circles) or 30mer (closed circles). For (B, E), each curve is representative of at least two independent experiments and each data point is the mean of duplicate measurements within a replicate. Errors bars are plus/minus one standard error of the mean and in most cases are too small to be visible. All fits have R2 ≥ 0.98. Statistics are given in Table S1. 30mer annealing and complementary competition experiments with longer DNA are shown in Figure S5.

Nap1 and DNA directly compete for H2A-H2B

Our result that Nap1 interacts with H2B in the vicinity of its L2 loop, prompted us to test if Nap1 and DNA compete for binding to H2A-H2B. To test for competition, we used a double-stranded 30 bp fragment that corresponds to the H2A-H2B-binding region of the 601 nucleosome positioning sequence (Vasudevan et al., 2010) (Figure S5A). Interaction between H2A-H2B and 30mer was confirmed by native-PAGE and the affinity determined using FRET (Figure 5C, Table S1). The 30mer was then used in a qualitative native-PAGE assay in which wild type or mutant 15 Nap1 was titrated against a constant amount of H2A-H2B•30mer. As described above, mutant 15 contains mutations in Nap1 α7 and has a weakened affinity for H2A-H2B. Titration of wild type Nap1 causes the disappearance of the H2A-H2B•30mer band, while titration of mutant 15 Nap1 has no effect (Figure 5D, left versus right). This reveals that wild type Nap1 readily competes with 30mer for H2A-H2B, while mutant 15 does not. A similar native-PAGE assay was also performed with 207 bp 601 DNA (Figure S5B). H2A-H2B and 207 bp 601 were mixed 7:1, which is congruent with approximately 1 H2A-H2B per 30 bp. Wild type Nap1 competes H2A-H2B•207 bp 601, causing the appearance of free DNA, while Nap1 mutant 15 has no effect. Hence, wild type Nap1 can compete H2A-H2B from both short and long DNA fragments, with α7 playing a critical role.

We also conducted quantitative FRET competition assays in solution at sub-Kd concentrations. Quantitative assays are essential to determine if the competition is a direct reflection of the relative affinities of H2A-H2B for wild type Nap1 and 30mer. The assay involves competing FRET between 488H2A-H2BT112C and excess 647N30mer with unlabeled Nap1 or 30mer. We find that FRET between H2A-H2B and 30mer is competed by either unlabeled Nap1 or unlabeled 30mer (Figure 5E). Nap1 competes more efficiently than 30mer, in proportion to its tighter affinity for H2A-H2B, suggesting direct competition (Table S1). In combination with the native-PAGE result, this means a stable ternary complex with Nap1, H2A-H2B and 30mer does not form. The competition data demonstrate that Nap1 prevents H2A-H2B from contacting 30 bp of DNA outside of a nucleosomal context. While it is seems likely that Nap1 blocks the H2B L2 loop through direct contact, it is not clear if or how Nap1 blocks the H2A L2 loop. There is an increase in H-bonding of the H2A L2 loop upon addition of Nap1 (Figure 2). We speculate that it may be blocked by the acidic C-terminal tail of Nap1 for which we did not retrieve any peptides, or through interactions between multiple copies of H2A brought together by Nap1 oligomerization beyond a homodimer.

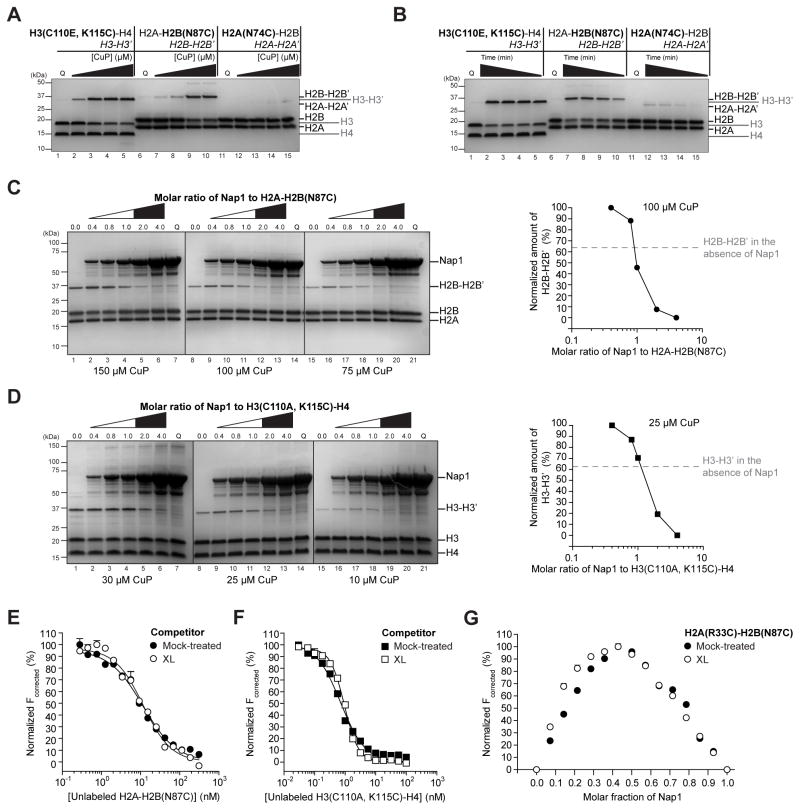

Nap1 levels determine if Nap1-bound histones are dimers or tetramers

Our analysis of the H/DX data has thus far focused on interactions between Nap1 and H2A-H2B. There is however, also potential for interactions between different H2A-H2B molecules bound to Nap1. Multiple copies of H2A-H2B may be brought together as Nap1 is a homodimer that can bind two copies of H2A-H2B (Andrews et al., 2008). One possibility is that the two copies of H2A-H2B bound to Nap1 form a tetramer through a four-helix bundle. This idea seems plausible as the four-helix bundle structural motif has been repeatedly used by pairs of other histone heterodimers. In the nucleosome, for example, four-helix bundles occur between the two copies of H3-H4, as well as between H2A-H2B and H3-H4 (Luger et al., 1997). The former involves the two copies of H3 (H3-H3′), while the latter involves H2B and H4 (H2B-H4). A Nap1-induced (H2A-H2B)2 four-helix bundle is also suggested by previous work with H3-H4 showing that Nap1-bound (H3-H4)2 contains a H3-H3′ four-helix bundle (Bowman et al., 2011). Nap1 is expected to recognize H2A-H2B and H3-H4 similarly, as they are structural homologs that bind Nap1 with comparable affinity and stoichiometry (Andrews et al., 2008).

If Nap1 induces formation of a (H2A-H2B)2 tetramer with a four-helix bundle it should be apparent in the H/DX data. In particular, Nap1 should reduce H/DX of the α2 and α3 helices in either H2A or H2B, depending on which histone mediates bundle formation. Helices homologous to α2 and α3 mediate contacts in the previously described H3-H3′ and H2B-H4 four-helix bundles (Figure S6A). Inspection of our H/DX data however reveals that Nap1 reduces exchange of these helices in both H2A and H2B (Figure 2). In the presence of Nap1, these helices display a > 2.0-fold reduction in % D at 10 seconds (Figure S2A, C). Thus while the H/DX data is consistent with a (H2A-H2B)2 four-helix bundle, it fails to determine if the bundle is mediated by H2A (H2A-H2A′) or H2B (H2B-H2B′). We propose that H2B is the most likely candidate as unlike H2A, H2B mediates bundle formation in the nucleosome. H2B is also structurally similar to H3, with both histones having a straight α2 helix and a long L1 loop when compared to either H4 or H2A (Figure S6B). This similarity is suggestive as a H3-H3′ four-helix bundle occurs in the (H3-H4)2 tetramer observed in solution, in the nucleosome and bound to Nap1 (Bowman et al., 2011; Luger et al., 1997; Winkler et al., 2012).

To experimentally determine if Nap1 induces a (H2A-H2B)2 tetramer with a four-helix bundle, we performed cross-linking experiments using either H2AN74C-H2B or H2A-H2BN87C in the presence and absence of Nap1. These mutants have cysteine substitutions ideally positioned to form a disulfide bond in a putative (H2A-H2B)2 tetramer with either a H2A-H2A′ or H2B-H2B′ four-helix bundle (Figure S6A). These putative tetramers were modeled based on the (H3-H4)2 tetramer. We catalyzed disulfide bond formation using copper (II) chelated with 1, 10-phenanthroline (CuP) (Kobashi, 1968) and used H3C110A, K115C-H4 as a positive control. At concentrations above 1 μM, H3-H4 forms a stable tetramer that can be cross-linked using CuP via H3K115C (Bowman et al., 2011; Winkler et al., 2012).

Initial experiments performed in the absence of Nap1 show that H2A-H2BN87C cross-links similarly to H3C110A, K115C-H4. Both mutants show increased cross-linking with increased CuP concentration (0–50 μM) and time (0–15 minutes), and maintain cross-linking up to 1M NaCl (Figure 6A–B, S6C). This contrasts with H2AN74C-H2B, which only cross-links at low salt (< 300 mM). Cross-linking at low salt is non-specific as we observed it for other cysteine mutants, such as H2AR33C-H2B and H2A-H2BT118C, which are located far from the putative four-helix bundle (data not shown). The similar cross-linking behavior of H2A-H2BN87C and H3C110A, K115C-H4, but not H2AN74C-H2B and H3C110A, K115C-H4, suggests that even in the absence of Nap1, H2A-H2B can form a transient tetramer with H2B-H2B′ interactions captured by cross-linking. This tetramer is unconventional as H2B-H2B′ interactions are not observed in the nucleosome and have not previously been detected in solution. The H2A-H2BN87C tetramer is less stable than the H3C110A, K115C-H4 tetramer, as more time and CuP are required to reach comparable levels of cross-linking. A transient H2A-H2B tetramer is consistent with the observation that H2A-H2B migrates as a dimer during gel filtration (Winkler et al., 2012).

Figure 6. Nap1-bound H2A-H2B forms a tetramer via H2B-H2B′ interactions.

(A–B) SDS-PAGE analysis of cross-linking of H3C110A, K115C-H4, H2A-H2BN87C or H2AN74C-H2B as a function of CuP concentration (A) or time (B). (C–D) SDS-PAGE analysis of cross-linking of H2A-H2BN87C (C) or H3C110A, K115C-H4 (D) in the presence of an increasing amount of Nap1. Three different CuP concentrations are shown. Lanes below the white region of the triangle have limited Nap1 relative to histones, while lanes below the filled region of the triangle have excess Nap1 relative to histones. Samples were analyzed in the absence of reducing agent and gels were stained with Coomassie Blue. Controls where quench is added prior to CuP are labeled Q. Quantification of H2B-H2B′ or H3-H3′ for the middle CuP concentration is shown. Maximum amount of cross-linking is set at 100%. (E–F) FRET between 10 nM 488H2A-H2BT118C and 1 nM 647NNap1 is competed with unlabeled H2A-H2BN87C (E) or H3C110A, K115C-H4 (F) that is cross-linked (XL, open) or mock-treated (closed). (G) Job plot with 647NNap1 and 488H2AR33C-H2BN87C that is cross-linked (XL, open) or mock-treated (closed). Total protein concentration is 140 nM. For (E–G), each curve is representative of at least two independent experiments and each data point is the mean of duplicate measurements within a replicate. Errors bars are plus/minus one standard error of the mean and in most cases are too small to be visible. All fits have R2 ≥ 0.95. Statistics are given in Table S1. Reagent preparation and complementary models or experiments are shown in Figure S6.

To determine the effect of Nap1 on histone tetramer formation, subsequent experiments involved histone cross-linking in the presence of an increasing amount of cysteine-free Nap1. These experiments reveal two trends for cross-linking of H2A-H2BN87C and H3C110A, K115C-H4. First, limiting amounts of Nap1 enhance histone cross-linking compared to the absence of Nap1 (Figure 6C–D, open triangle). This shows that when Nap1 is in short supply and all Nap1 histone-binding sites are occupied, the histones form tetramers on Nap1. Thus, Nap1-bound (H2A-H2B)2 can form a tetramer with H2B-H2B′ interactions. The second trend is that excess Nap1 inhibits histone cross-linking compared to the absence of Nap1 (Figure 6C–D, closed triangle). This inhibition is dose-dependent with higher amounts of Nap1 more effectively inhibiting histone cross-linking. Inhibition is not due to decreased CuP activity, as similar experiments with H2AN74C-H2B show an increase in cross-linking in the presence of Nap1, but no decrease in cross-linking as Nap1 is titrated (data not shown). The inhibition of cross-linking observed when Nap1 is in excess and some Nap1 histone-binding sites are free, is consistent with dimeric histones. Taken together, these data show that for H2A-H2BN87C and H3C110A, K115C-H4, the relative amount of Nap1 to histones regulates the oligomeric state of Nap1-bound histones.

Nap1 binds a constitutive H2A-H2B tetramer with H2B-H2B′ interactions

Although the cross-linking experiments provide strong support for the existence of an unconventional (H2A-H2B)2 tetramer formed by H2B-H2B′ interactions, we also performed experiments with a constitutive (H2A-H2BN87C)2 tetramer. This tetramer was cross-linked with high efficiency in the absence of Nap1, using conditions that minimized non-specific cross-linking of H2AN74C-H2B (Figure S6D). We compared the Nap1-binding affinity of this constitutive tetramer to mock treated H2A-H2BN87C using the modified competition assay described previously. Competition with cross-linked and mock-treated H2A-H2BN87C produce similar competition curves, with the cross-linked tetramer having a steeper slope indicative of a slightly elevated Hill coefficient (Figure 6E, Table S1). Comparable results were obtained with cross-linked and mock-treated H3C110A, K115C-H4, which is our positive control (Figure 6F, Table S1). As competitive ability is directly proportional to binding affinity, these data show that (H2A-H2BN87C)2 tetramer and mock-treated H2A-H2BN87C bind Nap1 with equal affinity. This implies that the Nap1-recognition site in H2A-H2B is not altered by constraining a (H2A-H2B)2 tetramer formed via H2B-H2B′ interactions.

To test if the cross-linked (H2A-H2B)2 tetramer engages both Nap1-binding sites, we performed stoichiometric analysis. Labeled H2A-H2B was obtained by refolding H2BN87C with H2AR33C that had been treated with fluorescent dye followed by a cysteine-blocker. Adequate sample preparation is indicated by the absence of cross-linking of the H2AR33C-H2B single mutant, as well as efficient cross-linking of the H2AR33C-H2BN87C double mutant (Figure S6E). Stoichiometries of 647NNap1 with cross-linked or mock-treated 488H2AR33C-H2BN87C were determined using Job plots (Olson and Buhlmann, 2011). Nap1 was decreased as histones were increased such that the total molar amount of protein remained constant. The stoichiometry is the point of maximum FRET. Both cross-linked and mock-treated 488H2AR33C-H2BN87C have maximum FRET at a Nap1 molar fraction of 0.43, or 1.3 H2A-H2B per Nap1 monomer (Figure 6G, Table S1). This value is slightly smaller than the theoretical value of 0.50, based on our previously reported stoichiometry of one H2A-H2B per Nap1 monomer or a (H2A-H2B)2 tetramer per Nap1 dimer (Andrews et al., 2008). The smaller value likely occurs as when in excess the histones interact non-specifically with Nap1. Regardless, the identical maxima obtained for cross-linked and mock-treated 488H2AR33C-H2BN87C shows they bind Nap1 with the same stoichiometry. The identical affinity and stoichiometry of Nap1 to H2A-H2B and a constitutive (H2A-H2B)2 tetramer, provides clear evidence that H2A-H2B bound to Nap1 can form a tetramer with H2B-H2B′ interactions. H2B thus mediates tetramer formation and directly contacts Nap1.

An important implication of our result that Nap1-bound (H2A-H2B)2 contains H2B-H2B′ interactions, is that Nap1 induces histone-histone contacts that occlude an H2A-H2B surface required for nucleosome formation. The H2B cysteine substitution used for cross-linking is located at the surface of H2B that forms a four-helix bundle with H4 in the nucleosome (Figure S6F). Constraining (H2A-H2B)2 in its Nap1-bound form should thus prevent nucleosome assembly. To test this, we performed nucleosome reconstitutions with mock-treated and cross-linked H2A-H2BN87C. Mock-treated H2A-H2BN87C formed nucleosomes with similar efficiency to wild type H2A-H2B, while cross-linked H2A-H2BN87C was less efficient (Figure S6G, compare lanes marked with green asterisk). Cross-linked H2A-H2BN87C caused the presence of unusual histone-DNA complexes with slow mobility in a native-PAGE gel (Figure S6G, yellow asterisk). The small amount of nucleosomes formed with cross-linked H2A-H2BN87C most likely represents the small population of H2A-H2BN87C that escaped cross-linking. The H2B-H2B′ interactions found in a Nap1-bound (H2A-H2B)2 tetramer thus interfere with a H2B surface that is required for nucleosome formation.

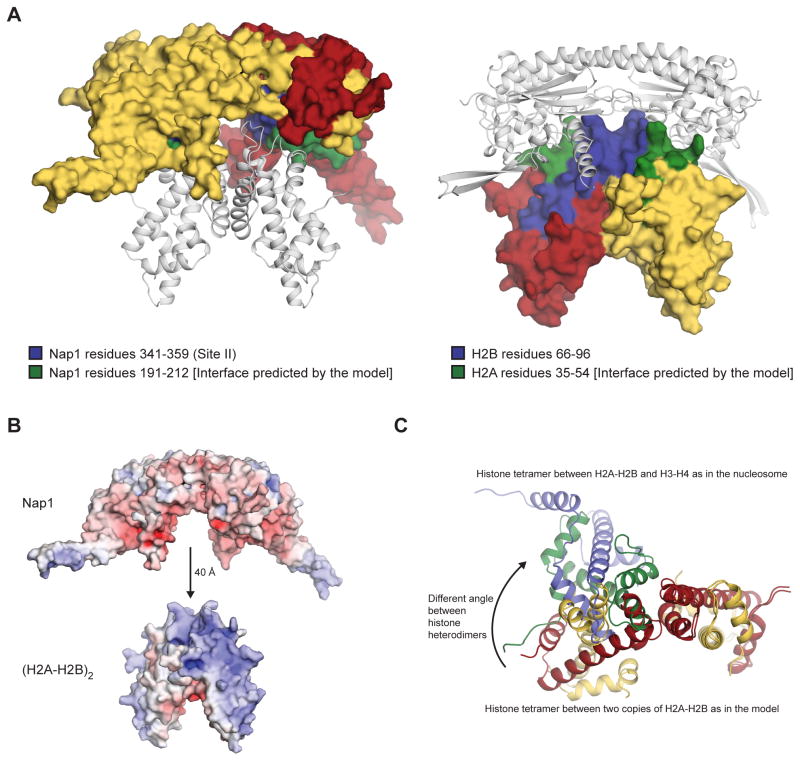

A (H2A-H2B)2 tetramer is spatially compatible with the Nap1 homodimer

Taken together, our experimental results have identified three features of the complex between Nap1 and H2A-H2B. These are that Nap1 α7-α8 (Site II) binds H2A-H2B, that H2B binds Nap1, and that (H2A-H2B)2 forms a tetramer with a H2B-H2B′ four-helix bundle. We next asked if these three independently derived features are compatible with each other in the context of the known structures of H2A-H2B and the Nap1 homodimer. To do this, we employed docking program HADDOCK, which can build a model of a protein complex based on restraints provided by the user (Dominguez et al., 2003; Karaca et al., 2010). We provided two sets of interaction restraints. One set was between H2B and Nap1 and was based on our H/DX and mutagenesis data, while the other set was between the two copies of H2B and was based on our H/DX and cross-linking data. We also enforced symmetry between of the two copies of H2A-H2B and made the two copies of the interacting regions of Nap1 and H2A-H2B identical. Notably, however, inclusion of symmetry restraints was not essential for the production of a feasible model of the complex between H2A-H2B and Nap1.

Docking with HADDOCK demonstrates that all of our experimental results are spatially compatible with each other, as well as with the known structures of H2A-H2B and Nap1. The best model (as judged by HADDOCK) has low intermolecular energy scores and highlights the shape and charge complementarity of interacting surfaces (Figure 7A–B, Table S2). It shows that the space between the identified Nap1 histone-binding sites can accommodate a (H2A-H2B)2 tetramer, as long as the four-helix bundle of the tetramer is proximal to Nap1. This is entirely consistent with our experimental data that H2B mediates both Nap1-binding and four-helix bundle formation. Excluding restraints between the two copies of H2B or placing H2A rather than H2B in direct contact with Nap1 fails to produce a model in keeping with all of the experimental data (see descriptions in Supplemental Experimental Data). The best model also suggests that the (H2A-H2B)2 tetramer bound to Nap1 may be slightly different to other histone tetramers. Comparison of (H2A-H2B)2 in the model with a (H2A-H2B)-(H4-H3) tetramer from the nucleosome, reveals a different angle between histone heterodimers (Figure 7C). This may indeed occur in the complex or may be a result of our conservative modeling approach that did not allow for movement between the two Nap1 chains. Flexing of the Nap1 chains is feasible and would account for the changes in H/DX observed at the Nap1 dimerization helix (Site I) upon interaction with H2A-H2B (Figure 1). Less well-scoring models differ from the best model in the angle between histone heterodimers or slightly rotate the (H2A-H2B)2 tetramer relative to Nap1.

Figure 7. Model of the complex between H2A-H2B and Nap1.

(A) Best HADDOCK model of the complex between (H2A-H2B)2 and the Nap1 homodimer. Statistics for the model are given in Table S2. In the left view, Nap1 is shown as a surface (Chain A is yellow and Chain B is red; residues 341–359 are blue and residues 191–212 are green) and H2A-H2B is shown as white cartoon. In the right view, (H2A-H2B)2 is shown as a surface (one heterodimer is red and the other is yellow; residue 66–96 are blue and residues 35–54 are green) and Nap1 is shown as white cartoon. Nap1 residues 341–359 and H2B residues 66–96 form the interface between Nap1 and H2A-H2B according to H/DX and mutagenesis data (blue surface). These regions were included in the modeling restraints. The model predicts additional contacts between Nap1 and H2A that were not included in the restraints, but are observed in the H/DX data. In particular, Nap1 residues 191–212 may contact H2A residues 35–54 (green surface). (B) Electrostatic surface potential of Nap1 and (H2A-H2B)2 shown on the same scale (−10 to +10 as color changes from red to blue). The two structures are oriented as in the best HADDOCK model, except that (H2A-H2B)2 has been translated 40 Å downwards for easy visualization of shape complementarity. (C) Comparison of the four-helix bundles formed between H3-H4 and H2A-H2B in the nucleosome, and that between the two copies of H2A-H2B in the best HADDOCK model. The histone tetramers were superposed by the H2B chain shown on the right. H2A residues 23–100 are yellow, H2B residues 36–105 are red, H3 is blue and H4 is green.

The best model derived from docking also predicts additional contacts between Nap1 and H2A-H2B that were not specified in the restraints. In particular, the model places Nap1 α4-α5 in close proximity to the H2A L1 loop (Figure 7A, green surface). Re-inspection of the H/DX data shows that these regions are in fact protected from exchange upon complex formation (Figures 1–2). This is particularly the case for Nap1 α4-α5, which shows a notable fold-change in % D with and without H2A-H2B after 104 seconds (Figure S1D). The prediction of novel interactions that are consistent with our experimental data reinforces the feasibility of the best model. Ultimately, this model verifies the compatibility of the three features of the complex between Nap1 and H2A-H2B that we derived independently and in an unbiased fashion.

Discussion

Characterizing histones with and without their cognate chaperone at the biochemical and structural level is likely to provide key insight into the biological mechanism and context of histone chaperone activity. Using H/DX we show that in the absence of a chaperone, H2A-H2B frequently samples unfolded conformations. The rate of sampling depends on the ionic strength and does not affect heterodimer formation by H2A and H2B. This tendency of H2A-H2B to unfold suggests a need for chaperones to stabilize H2A-H2B and either prevent its inclusion in non-functional complexes or promote its deposition into chromatin. Consistent with this, we show that the chaperone Nap1 does reduce conformational sampling of H2A-H2B by stabilizing H-bonds throughout the histone fold domains of both H2A and H2B, in a manner that is consistent with histone fold dimerization as observed in the nucleosome structure. Nap1 has a global effect insofar as it influences H-bonds beyond those involved at the binding interface. Partial unfolding of histones and chaperone effects beyond direct contact points have recently been reported for centromeric histones and their chaperones (Bassett et al., 2012; Hong et al., 2013). It is likely that a stable conformation of H2A-H2B may only be found in the context of a chaperone or other histones and DNA in the nucleosome.

Combined with complementary techniques, our H/DX data also identifies major restraints in the molecular organization of the complex between H2A-H2B and Nap1. We first show that the helical underside of Nap1 directly interacts with H2B in the vicinity of its L2 loop. These surfaces have complementary charge distributions, in keeping with previous reports that their interaction depends on ionic strength (Park and Luger, 2006). The helical underside of Nap1 ortholog Set is also thought to play a role in histone binding (Muto et al., 2007). Mutagenesis of H2B or Nap1 side chains at this interface however fails to completely abrogate the interaction in vitro. This implies additional involvement of backbone atoms, consistent with Nap1 binding both H2A-H2B and H3-H4 with very similar affinities (Andrews et al., 2008). These histones share structural but not sequence homology. The histone-binding site in Nap1 also shows only moderate sequence conservation between orthologs (Park and Luger, 2006).

Another restraint we identify is that two copies of Nap1-bound H2A-H2B form a tetramer. We show that this tetramer occurs transiently in the absence of Nap1 and contains contacts between the two copies of H2B, rather than H2A, most probably similar to those observed in other histone four-helix bundles. These findings are based on observed cross-linking of strategically located cysteine substitutions in H2B, but not H2A. A Nap1-bound histone tetramer is in keeping with previous reports that H3-H4 retains it nucleosomal tetrameric form when bound to Nap1 (Bowman et al., 2011). The similar role of H2B and H3 in four-helix bundle formation, both on Nap1 and in the nucleosome, reflects their high structural homology. We postulate that histone protein four-helix bundles in general are responsible for stabilizing the histone fold. This is supported by the folded nature of histones in the presence of Nap1, the nucleosome, and tetrameric H3-H4, but not in H2A-H2B alone (Black et al., 2007; Black et al., 2004). However, although homology, H/DX, cross-linking and modeling, all imply that the interactions between two copies of H2B are like those in other histone four-helix bundles, we cannot completely rule out alternative conformations.

For both H2A-H2B and H3-H4, the restraint of tetramer formation applies only when Nap1 is limiting or stoichiometric and all histone-binding sites are occupied. Under the converse conditions, when Nap1 is in excess and some histone-binding sites are free, the histones are in a dimeric conformation. This is not surprising for predominantly dimeric H2A-H2B, but does reveal that excess Nap1 can bind and spatially separate H3-H4 dimers. This is consistent with a tighter affinity between H3-H4 dimer and Nap1, than between two H3-H4 dimers (Andrews et al., 2008; Winkler et al., 2012). Binding of dimeric H3-H4 to Nap1 has not been observed previously as stoichiometric amounts of Nap1 are typically used (Bowman et al., 2011).

The validity of the identified restraints is reinforced by their spatial compatibility with each other, and the known structures of histones and Nap1 alone. The two-fold symmetry of the Nap1 homodimer is matched by the symmetry of the four-helix bundle structural motif. The space between the two identified Nap1 histone-binding sites can fit a (H2A-H2B)2 tetramer with dimensions similar to other histone tetramers. This requires the four-helix bundle to be proximal to Nap1, consistent with our result that H2B mediates both tetramer formation and Nap1 binding. We confirmed this realistic geometry by submitting our restraints to docking program HADDOCK (Dominguez et al., 2003; Karaca et al., 2010). This produces a feasible model with low intermolecular energy scores. The model assumes histone tetramer formation is driven by the Nap1 homodimer, rather than a higher-order oligomer, and does not incorporate the changes observed at the Nap1 dimerization helix or in H2A. Based on structural comparison of Nap1 and homolog Set (Muto et al., 2007), we speculate that changes at the Nap1 dimerization helix are due to flexing of or changes in the relative orientation of Nap1 chains upon interaction with H2A-H2B.

Our insights into the organization of the complex ultimately suggest that Nap1 occludes H2A-H2B interfaces utilized in the nucleosome. Blocking histone interfaces used in the nucleosome is an emerging property of histone chaperones that has been reported for Asf1, Scm3, HJURP, and Chz1 (Cho and Harrison, 2011; Elsasser et al., 2012; English et al., 2006; Hu et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2012; Zhou et al., 2008; Zhou et al., 2011). We experimentally demonstrate applicability to Nap1 by showing that Nap1 and DNA directly compete for H2A-H2B. The assumption is that H2A-H2B interacts with the 30mer used in our assay via its L1 and L2 loops, similar to how it contacts DNA in the nucleosome. The observed direct competition differs from our previously published model, where a ternary complex between Nap1, H2A-H2B and DNA was proposed based on a negative FRET result (Andrews et al., 2010). Our recent data, combined with our inability to detect a stable ternary complex with other biochemical and biophysical approaches, leads us to favor direct competition. While it is clear that Nap1 blocks the H2B L2 loop through direct contact, it is not clear if or how Nap1 blocks the H2A L2 loop. Notably, we do observe an increase in H-bonding of the H2A L2 loop upon addition of Nap1. We speculate that it may be blocked by the acidic C-terminal tail of Nap1 for which we do not retrieve any peptides, or through interactions between multiple copies of H2A brought together by Nap1 oligomerization beyond a homodimer.

Consistent with Nap1 occluding histone interfaces required for nucleosome formation, we also show that H2A-H2B constrained in its Nap1-bound tetrameric form by cross-linking, is incompetent for nucleosome reconstitution. The H2B-H2B′ interaction in a H2A-H2B tetramer buries the H2B region that binds H4 in the nucleosome. It is important to note, however, that this depends on H2A-H2B tetramer formation and thus requires Nap1 to be limiting or stoichiometric. Nap1 thus has the potential to block both histone-histone and histone-DNA contacts observed in the nucleosome. An occlusion mechanism has not previously been shown for Nap1. Taken together, our data provide a framework for Nap1 histone chaperone function by uncovering novel features of H2A-H2B in solution and revealing the arrangement of Nap1-bound histones.

Experimental Procedures

Reagents

Recombinant histones were purified and refolded according to standard protocols (Luger et al., 1999). Yeast Nap1 proteins were expressed and purified similar to described previously (McBryant et al., 2003), except that they contained three (C200A, C249A, C272A) or four (plus C414A) mutations and were from a pBAT4 or pHAT4 plasmid respectively. NAP1 was deleted in the parental yeast strain bar1Δ (MATα, his3Δ1, ura3Δ0, leu2Δ0, met15Δ0, bar1Δ::KanMX4) (Open Biosystems) using established protocols (Longtine et al., 1998). Unlabeled and 5′ Atto 647N-labeled 30mer oligos were purchased from EGT. 207 bp 601 DNA (Lowary and Widom, 1998) was prepared as described previously (Dyer et al., 2004).

Biochemistry and Biophysics

Detailed protocols for the H/DX reactions, proteolysis, mass spectrometry and data analysis are outlined in Supplemental Experimental Procedures. The circular dichroism, sedimentation velocity, FRET, yeast phenotypic, native-PAGE, cross-linking, nucleosome reconstitution and docking assays are also described in Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Nap1 stabilizes the fold of H2A-H2B

An α-helical region of Nap1 directly binds H2B

Nap1 and DNA directly compete for H2A-H2B

Two copies of H2A-H2B bound to Nap1 can form a tetramer with contacts between H2B

Acknowledgments

We thank Pamela Dyer and the W. M. Keck Protein Expression and Purification Facility, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Colorado State University for histone purification and Alyson White for purifying nucleosome DNA. We are grateful to Uma Muthurajan for collection and analysis of the analytical ultracentrifugation data, and to Leland Mayne and Palaniappan Chetty for assistance with MS. We are also grateful to ZhongYuan Kan for guidance with ExMS software, and Ezgi Karaca for guidance with HADDOCK. We thank Luger laboratory members for helpful discussions relating to the manuscript.

This work was supported in part by grants from the NIH (P01-GM088409 to K.L. and L.S.; GM067777 to K.L., and GM082989 to B.E.B.), a Career Award in the Biomedical Sciences from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund (B.E.B.), and a Rita Allen Foundation Scholar Award (B.E.B.). T.P. was supported by the University of Pennsylvania Structural Biology Training Grant (NIH GM08275). K.L. and S.D. are also supported by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Andrews AJ, Chen X, Zevin A, Stargell LA, Luger K. The histone chaperone Nap1 promotes nucleosome assembly by eliminating nonnucleosomal histone DNA interactions. Mol Cell. 2010;37:834–842. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.01.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews AJ, Downing G, Brown K, Park YJ, Luger K. A thermodynamic model for Nap1-histone interactions. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:32412–32418. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805918200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnan C, Saperas N, Prieto C, Chiva M, Ausio J. Interaction of nucleoplasmin with core histones. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:31319–31324. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305560200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks DD, Gloss LM. Equilibrium folding of the core histones: the H3-H4 tetramer is less stable than the H2A-H2B dimer. Biochemistry. 2003;42:6827–6839. doi: 10.1021/bi026957r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassett EA, DeNizio J, Barnhart-Dailey MC, Panchenko T, Sekulic N, Rogers DJ, Foltz DR, Black BE. HJURP uses distinct CENP-A surfaces to recognize and to stabilize CENP-A/histone H4 for centromere assembly. Dev Cell. 2012;22:749–762. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black BE, Brock MA, Bedard S, Woods VL, Jr, Cleveland DW. An epigenetic mark generated by the incorporation of CENP-A into centromeric nucleosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:5008–5013. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700390104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black BE, Foltz DR, Chakravarthy S, Luger K, Woods VL, Jr, Cleveland DW. Structural determinants for generating centromeric chromatin. Nature. 2004;430:578–582. doi: 10.1038/nature02766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowman A, Ward R, Wiechens N, Singh V, El-Mkami H, Norman DG, Owen-Hughes T. The histone chaperones Nap1 and Vps75 bind histones H3 and H4 in a tetrameric conformation. Mol Cell. 2011;41:398–408. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho US, Harrison SC. Recognition of the centromere-specific histone Cse4 by the chaperone Scm3. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:9367–9371. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1106389108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Anna JA, Jr, Isenberg I. Interactions of histone LAK (f2a2) with histones KAS (f2b) and GRK (f2a1) Biochemistry. 1974;13:2098–2104. doi: 10.1021/bi00707a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Koning L, Corpet A, Haber JE, Almouzni G. Histone chaperones: an escort network regulating histone traffic. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:997–1007. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez C, Boelens R, Bonvin AM. HADDOCK: a protein-protein docking approach based on biochemical or biophysical information. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:1731–1737. doi: 10.1021/ja026939x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyer PN, Edayathumangalam RS, White CL, Bao Y, Chakravarthy S, Muthurajan UM, Luger K. Reconstitution of nucleosome core particles from recombinant histones and DNA. Methods Enzymol. 2004;375:23–44. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(03)75002-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsasser SJ, D’Arcy S. Towards a mechanism for histone chaperones. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1819:211–221. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2011.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsasser SJ, Huang H, Lewis PW, Chin JW, Allis CD, Patel DJ. DAXX envelops a histone H3.3-H4 dimer for H3.3-specific recognition. Nature. 2012;491:560–565. doi: 10.1038/nature11608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Englander SW. Hydrogen exchange and mass spectrometry: A historical perspective. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2006;17:1481–1489. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2006.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- English CM, Adkins MW, Carson JJ, Churchill ME, Tyler JK. Structural basis for the histone chaperone activity of Asf1. Cell. 2006;127:495–508. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.08.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampsey M. A review of phenotypes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1997;13:1099–1133. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(19970930)13:12<1099::AID-YEA177>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen JC, Wexler BB, Rogers DJ, Hite KC, Panchenko T, Ajith S, Black BE. DNA binding restricts the intrinsic conformational flexibility of methyl CpG binding protein 2 (MeCP2) J Biol Chem. 2011;286:18938–18948. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.234609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hieb AR, D’Arcy S, Kramer MA, White AE, Luger K. Fluorescence strategies for high-throughput quantification of protein interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:e33. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hondele M, Stuwe T, Hassler M, Halbach F, Bowman A, Zhang ET, Nijmeijer B, Kotthoff C, Rybin V, Amlacher S, et al. Structural basis of histone H2A-H2B recognition by the essential chaperone FACT. Nature. 2013;499:111–114. doi: 10.1038/nature12242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong J, Feng H, Zhou Z, Ghirlando R, Bai Y. Identification of functionally conserved regions in the structure of the chaperone/CenH3/H4 complex. J Mol Biol. 2013;425:536–545. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2012.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoofnagle AN, Resing KA, Ahn NG. Protein analysis by hydrogen exchange mass spectrometry. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2003;32:1–25. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.32.110601.142417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu H, Liu Y, Wang M, Fang J, Huang H, Yang N, Li Y, Wang J, Yao X, Shi Y, et al. Structure of a CENP-A-histone H4 heterodimer in complex with chaperone HJURP. Genes Dev. 2011;25:901–906. doi: 10.1101/gad.2045111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamtekar S, Hecht MH. Protein Motifs. 7. The four-helix bundle: what determines a fold? Faseb J. 1995;9:1013–1022. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.9.11.7649401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kan ZY, Mayne L, Chetty PS, Englander SW. ExMS: data analysis for HX-MS experiments. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2011;22:1906–1915. doi: 10.1007/s13361-011-0236-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karaca E, Melquiond AS, de Vries SJ, Kastritis PL, Bonvin AM. Building macromolecular assemblies by information-driven docking: introducing the HADDOCK multibody docking server. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2010;9:1784–1794. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M000051-MCP201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karantza V, Baxevanis AD, Freire E, Moudrianakis EN. Thermodynamic studies of the core histones: ionic strength and pH dependence of H2A-H2B dimer stability. Biochemistry. 1995;34:5988–5996. doi: 10.1021/bi00017a028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobashi K. Catalytic oxidation of sulfhydryl groups by o-phenanthroline copper complex. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1968;158:239–245. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(68)90136-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu CP, Xiong C, Wang M, Yu Z, Yang N, Chen P, Zhang Z, Li G, Xu RM. Structure of the variant histone H3.3-H4 heterodimer in complex with its chaperone DAXX. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2012;19:1287–1292. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longtine M, McKenzie A, 3rd, Demarini DJ, Shah NG, Wach A, Brachat A, Philippsen P, JRP Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1998;14:953–961. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199807)14:10<953::AID-YEA293>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowary PT, Widom J. New DNA sequence rules for high affinity binding to histone octamer and sequence-directed nucleosome positioning. J Mol Biol. 1998;276:19–42. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luger K, Mader AW, Richmond RK, Sargent DF, Richmond TJ. Crystal structure of the nucleosome core particle at 2.8 A resolution. Nature. 1997;389:251–260. doi: 10.1038/38444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luger K, Rechsteiner TJ, Richmond TJ. Expression and purification of recombinant histones and nucleosome reconstitution. Methods Mol Biol. 1999;119:1–16. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-681-9:1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luger K, Richmond TJ. DNA binding within the nucleosome core. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1998;8:33–40. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(98)80007-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBryant SJ, Park YJ, Abernathy SM, Laybourn PJ, Nyborg JK, Luger K. Preferential binding of the histone (H3-H4)2 tetramer by NAP1 is mediated by the amino-terminal histone tails. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:44574–44583. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305636200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muto S, Senda M, Akai Y, Sato L, Suzuki T, Nagai R, Senda T, Horikoshi M. Relationship between the structure of SET/TAF-Ibeta/INHAT and its histone chaperone activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:4285–4290. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603762104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson EJ, Buhlmann P. Getting more out of a Job plot: determination of reactant to product stoichiometry in cases of displacement reactions and n:n complex formation. J Org Chem. 2011;76:8406–8412. doi: 10.1021/jo201624p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park YJ, Luger K. The structure of nucleosome assembly protein 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:1248–1253. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508002103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasudevan D, Chua EY, Davey CA. Crystal structures of nucleosome core particles containing the ‘601’ strong positioning sequence. J Mol Biol. 2010;403:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White CL, Suto RK, Luger K. Structure of the yeast nucleosome core particle reveals fundamental changes in internucleosome interactions. Embo J. 2001;20:5207–5218. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.18.5207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler DD, Zhou H, Dar MA, Zhang Z, Luger K. Yeast CAF-1 assembles histone (H3-H4)2 tetramers prior to DNA deposition. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:10139–10149. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Worth CL, Preissner R, Blundell TL. SDM--a server for predicting effects of mutations on protein stability and malfunction. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:W215–222. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue YM, Kowalska AK, Grabowska K, Przybyt K, Cichewicz MA, Del Rosario BC, Pemberton LF. Histone Chaperones Nap1 and Vps75 Regulate Histone Acetylation during Transcription Elongation. Mol Cell Biol. 2013;33:1645–1656. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01121-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z, Feng H, Hansen DF, Kato H, Luk E, Freedberg DI, Kay LE, Wu C, Bai Y. NMR structure of chaperone Chz1 complexed with histones H2A.Z-H2B. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15:868–869. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z, Feng H, Zhou BR, Ghirlando R, Hu K, Zwolak A, Miller Jenkins LM, Xiao H, Tjandra N, Wu C, et al. Structural basis for recognition of centromere histone variant CenH3 by the chaperone Scm3. Nature. 2011;472:234–237. doi: 10.1038/nature09854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.