Abstract

Background

Phylogenetic analyses of jawed vertebrates based on mitochondrial sequences often result in confusing inferences which are obviously inconsistent with generally accepted trees. In particular, in a hypothesis by Rasmussen and Arnason based on mitochondrial trees, cartilaginous fishes have a terminal position in a paraphyletic cluster of bony fishes. No previous analysis based on nuclear DNA-coded genes could significantly reject the mitochondrial trees of jawed vertebrates.

Results

We have cloned and sequenced seven nuclear DNA-coded genes from 13 vertebrate species. These sequences, together with sequences available from databases including 13 jawed vertebrates from eight major groups (cartilaginous fishes, bichir, chondrosteans, gar, bowfin, teleost fishes, lungfishes and tetrapods) and an outgroup (a cyclostome and a lancelet), have been subjected to phylogenetic analyses based on the maximum likelihood method.

Conclusion

Cartilaginous fishes have been inferred to be basal to other jawed vertebrates, which is consistent with the generally accepted view. The minimum log-likelihood difference between the maximum likelihood tree and trees not supporting the basal position of cartilaginous fishes is 18.3 ± 13.1. The hypothesis by Rasmussen and Arnason has been significantly rejected with the minimum log-likelihood difference of 123 ± 23.3. Our tree has also shown that living holosteans, comprising bowfin and gar, form a monophyletic group which is the sister group to teleost fishes. This is consistent with a formerly prevalent view of vertebrate classification, although inconsistent with both of the current morphology-based and mitochondrial sequence-based trees. Furthermore, the bichir has been shown to be the basal ray-finned fish. Tetrapods and lungfish have formed a monophyletic cluster in the tree inferred from the concatenated alignment, being consistent with the currently prevalent view. It also remains possible that tetrapods are more closely related to ray-finned fishes than to lungfishes.

Background

The evolutionary relationship among jawed vertebrates is currently a controversial issue. Cartilaginous fishes are traditionally considered to be ancestral to other jawed vertebrates (Figure 1A). Arnason and colleagues challenged the traditional view, based on phylogenetic analyses of complete mitochondrial sequences from several vertebrates [1-3]. According to their mitochondrial tree (Figure 1B), cartilaginous fishes have a terminal position in the phylogeny of bony fishes (coelacanth, lungfishes, bichirs, teleost fishes and other ray-finned fishes), implying that bony fishes are ancestral to cartilaginous fishes. Furthermore, the mitochondrial tree shows a basal split between tetrapods and other jawed vertebrates.

Figure 1.

Two hypotheses on jawed vertebrates. (A) Traditional view. (B) Mitochondrial tree proposed by Arnason's group [1-3].

Phylogenetic analyses based on mitochondrial sequences, however, often result in misleading trees when distantly related vertebrates are compared [4-7]. Some efforts have been made by several groups to obtain the robust phylogenetic trees of jawed vertebrates based on nuclear DNA-coded genes. In the LSU rRNA tree by Zardoya and Meyer [6], the basal position of cartilaginous fishes is not significantly supported; the bootstrap probabilities are 72%, 68% and 74%, for the maximum parsimony (MP) method, the neighbor joining (NJ) method and the maximum likelihood (ML) method, respectively. On the basis of presence or absence of insertions or deletions within conserved sequences [8], Venkatesh et al.[9] claimed to have found robust molecular evidence (molecular synapomorphy) against the mitochondrial tree [1-3]. However, their tree is basically an unrooted tree of major groups of jawed vertebrates as pointed out by Dimmick [10], because none of the molecular synapomorphies they found included an outgroup (cyclostomes or lancelets). Apart from the position of bichir, the tree by Venkatesh et al. is equivalent to that by Rasmussen et al., when compared as unrooted trees.

Martin [11] analyzed multiple nuclear DNA-coded genes and the hypothesis by Rasmussen et al. [1-3] could not be refuted. Hedges[12] analyzed 10 nuclear DNA-coded genes from two cyclostomes and three jawed vertebrates, and concluded the basal position of cartilaginous fishes in the jawed vertebrate tree. Takezaki et al. [13] confirmed this finding based on a comparison of 31 nuclear DNA-coded genes. Because only a single bony fish lineage represented by teleost fishes is included in these analyses, it remains possible that other bony fishes (lungfishes or bichir) are more deeply branching than cartilaginous fishes are. If it is the case, one cannot refute the hypothesis by Rasmussen and Arnason [3] that bony fishes are ancestral to cartilaginous fishes. The phylogenetic position of bichir is particularly important; bichir is often inferred to be the outgroup to all other jawed vertebrates in mitochondrial trees, when amphibian data is included in comparison (data not shown).

The phylogenetic relationship amongst teleost fishes and two holosteans is also controversial. Living holosteans, comprising bowfin and gar, are possible sister groups of teleost fishes [14,15]. All of three possible topologies (Figure 2A,2B,2C) were proposed by morphologists to date (see references cited in [15] and [16]). Partial mitochondrial and LSU rRNA data, on the other hand, do not support any of these morphology-based trees at a statistically significant level [17,18]. Venkatesh et al. [9] noted the possibility of an alternative tree (Figure 2D) based on a molecular synapomorphy. Inoue et al. [16] recently reported that this tree was supported by complete mitochondrial sequences. Mitochondrial sequences, however, may not be suitable for inferring phylogenetic relationships among such distantly related groups [6,19].

Figure 2.

Four hypotheses of phylogenetic relationship among ray-finned fishes. (A) Formerly accepted view. (B) Currently accepted view. (C) An alternative hypothesis by Olsen [42]. (D) Mitochondrial tree by Inoue et al. [16].

To test the mitochondrial trees at a statistically significant level, it is therefore necessary to perform phylogenetic analyses based on nuclear DNA-coded genes. There is, however, a possible error from paralogous comparisons when a nuclear DNA-coded gene tree is used for inferring the phylogenetic relationship of organisms. To avoid this, we selected basically single copy genes, such as enzymes in glycolysis, which are evolving at roughly constant rates over a wide range of animal taxa [20,21]. Since their evolutionary rates are generally low, no single gene amongst them has detailed phylogenetic information. Thus a large amount of sequence is needed for a statistically solid inference.

We have cloned and sequenced seven nuclear DNA-coded genes comprising ~3,000 amino acid residues in total, from eleven jawed vertebrate species, two cyclostomes (lamprey and/or hagfish) and a lancelet. These amino acid sequences, together with those available from the DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank databases, were subjected to phylogenetic analyses and statistical tests based on the ML method. We report here that the nuclear DNA-coded gene tree differs sharply from the mitochondrial tree on the two phylogenetic problems of jawed vertebrates; our tree supports the deepest position of cartilaginous fishes in jawed-vertebrate phylogeny, and the monophyly of holosteans.

Results and discussion

Phylogenetic tree inference

Teleost fishes have two TPI genes (TPI-A and TPI-B) [22]; A. baerii has two ALDa genes (AB111402 and AB111403); mammals have two PGK genes (M11968 and X05246 for human, M15668 and M17299 for mouse); and the mouse has two G6PD genes (Z84471 and AF326207). Each of these four gene pairs is shown to have multiplied within the respective taxonomic group by preliminary phylogenetic analyses. To avoid 'long branch attraction' (LBA) artifact [23], the slowly evolving counterpart for each of these gene pairs was selected for phylogenetic inference: O. latipes ortholog of TPI-B, AB111402 for A. baerii ALDa, M11968 for human PGK, M15668 for mouse PGK and AF326207 for mouse G6PD. Cyclostomes have muscle and non-muscle types of aldolase (ALD) genes [24]. Although the relationship between these two cyclostome ALD genes and three ALD genes (a, b and c) from jawed vertebrates is not clearly resolved, each of the jawed-vertebrate ALD genes was inferred to be orthologous [25]. The muscle-type ALD gene of hagfish, the non-muscle-type ALD gene of hagfish and the non-muscle-type ALD gene of lamprey were used as outgroups for ALDa, ALDb and ALDc of jawed vertebrates, respectively.

For each of the seven proteins, the amino acid sequences from 15 vertebrate species listed in Materials and methods have been aligned, and phylogenetic tree analyses have been carried out for regions comprising 317 amino acid residues (aa) in ALDa, 316aa in ALDb, 317aa in ALDc, 463aa in G6PD, 940aa in GAG, 383aa in PGK and 206aa in TPI, for each of which unambiguous alignment is possible. The total data set of 2,942aa was subjected to phylogenetic analyses based on the GAMT program [26] as described in materials and methods.

We have selected the candidate topologies – a set of topologies with log-likelihood values close to that of the ML tree – from seven protein data sets as described in Materials and Methods. The numbers of candidate topologies selected are 379 from the ALDa data set, 91 from the ALDb data set, 1,121 from the ALDc data set, 665 from the G6PD data set, 11 from the GAG data set, 652 from the PGK data set and 2,860 from the TPI data set, and 103 from the concatenated alignment. Excluding identical topologies, a total of 5,801 topologies were subjected to further analyses as the candidate topologies. For each candidate topology, the likelihood value of totalml and that of concatenated alignment were computed.

Figure 3 shows the ML tree inferred from the concatenated alignment. This tree strongly supports the basal position of cartilaginous fishes and the monophyly of holosteans, although individual trees inferred from each of seven proteins did not give statistically significant results, probably because of limited phylogenetic information held in a single gene (data not shown). Tables 1 and 2 show the ML topology and some topologies with large likelihood values inferred from concatenated alignment analysis and totalml analysis, respectively. Each table includes only topologies with P-values larger than 5% calculated by the Kishino-Hasegawa (KH) test. Note that the ML tree in totalml analysis (topology b in Table 2) differs from that in concatenated alignment analysis (Figure 3 and topology a in Table 1).

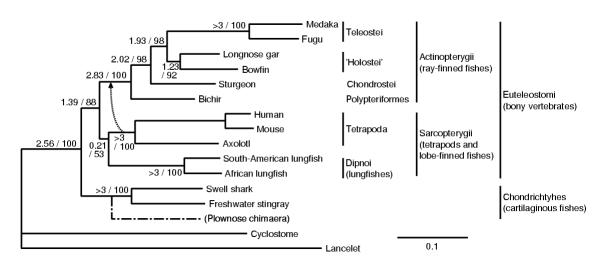

Figure 3.

The maximum likelihood tree inferred from the concatenated amino acid sequences (2,942 residues) of seven proteins. Reliability index [26] and the bootstrap probability for each branch are indicated before and after a slant, respectively. This tree corresponds to topology a in Tables 1 and 2. Topology b in Tables 1 and 2 is indicated by a dotted arrow. A dash-dotted line indicates the position of plownose chimaera inferred from six proteins. Branch lengths are proportional to accumulated amino acid substitutions.

Table 1.

Log-likelihood differences based on the concatenated alignment

| P-values | ||||||

| Topology | Δ ln Li ± σi | KH | AU | BPP | BP | |

| a ((((tp,lu),(((tl,(ga,bo)),st),bi)),ca),out) | (A, A) | ML | 0.59 | 0.88 | 0.89 | 0.44 |

| b ((((tp,(((tl,(ga,bo)),st),bi)),lu),ca),out) | (A, A) | 2.08 ± 9.55 | 0.41 | 0.74 | 0.11 | 0.33 |

| c (((tp,(lu,(((tl,(ga,bo)),st),bi))),ca),out) | (A, A) | 9.88 ± 7.57 | 0.10 | 0.14 | 0.00 | 0.02 |

| d ((((tp,lu),((((tl,bo),ga),st),bi)),ca),out) | (A, B) | 16.6 ± 11.6 | 0.08 | 0.19 | 0.00 | 0.04 |

| e ((((tp,lu),ca),(((tl,(ga,bo)),st),bi)),out) | (-, A) | 18.3 ± 13.1 | 0.09 | 0.21 | 0.00 | 0.03 |

| f ((((tp,((((tl,bo),ga),st),bi)),lu),ca),out) | (A, B) | 18.6 ± 15.0 | 0.11 | 0.14 | 0.00 | 0.03 |

| g (((tp,((((tl,(ga,bo)),st),bi),ca)),lu),out) | (-, A) | 22.0 ± 10.7 | 0.07 | 0.20 | 0.00 | 0.03 |

| h (((tp,(lu,ca)),(((tl,(ga,bo)),st),bi)),out) | (-, A) | 22.3 ± 15.7 | 0.08 | 0.20 | 0.00 | 0.02 |

| i ((((tp,(((tl,(ga,bo)),st),bi)),ca),lu),out) | (-, A) | 22.6 ± 15.8 | 0.08 | 0.11 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| j ((((tp,((((tl,ga),bo),st),bi)),lu),ca),out) | (A, C) | 24.0 ± 14.4 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| k ((((tp,ca),lu),(((tl,(ga,bo)),st),bi)),out) | (-, A) | 24.1 ± 15.5 | 0.06 | 0.14 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| l (((tp,(((tl,(ga,bo)),st),bi)),(lu,ca)),out) | (-, A) | 25.7 ± 15.4 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

Topologies that are not significantly rejected (P-value > 0.05) by the Kishino-Hasegawa (KH) test are listed. P-values by the approximately unbiased (AU) test, the Bayesian posterior probability (BPP), and the bootstrap probability (BP) are also shown for each topology. Abbreviations for species names are: tp, tetrapods; lu, lunfishes; tl, teleost fishes; bo, bowfin; ga, gar; st, sturgeon; bi, bichir; ca, cartilaginous fishes; out, outgroup. Corresponding hypotheses in Figures 1 and 2 are also shown; (A, B) at topology d, for example, indicates that topology d corresponds to Figure 1A and Figure 2B.

Table 2.

Log-likelihood differences based on totalml analysis

| Inference from each protein | P-values | ||||||||||||

| Topology | ALDa | ALDb | ALDc | G6PD | GAG | PGK | TPI | Δ ln Li ± σi | KH | AU | BPP | BP | |

| b ((((tp,(((tl,(ga,bo)),st),bi)),lu),ca),out) | (A, A) | 0.2 | 1.6 | 1.3 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.6 | 1.0 | ML | 0.67 | 0.93 | 0.99 | 0.45 |

| a ((((tp,lu),(((tl,(ga,bo)),st),bi)),ca),out) | (A, A) | 1.0 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 1.7 | 1.1 | 5.30 ± 12.2 | 0.33 | 0.76 | 0.01 | 0.23 |

| c (((tp,(lu,(((tl,(ga,bo)),st),bi))),ca),out) | (A, A) | 1.0 | 1.7 | 1.3 | 0.6 | 1.2 | 1.7 | 1.2 | 13.5 ± 11.0 | 0.11 | 0.28 | 0.00 | 0.03 |

| f ((((tp,((((tl,bo),ga),st),bi)),lu),ca),out) | (A, B) | 0.2 | 2.0 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.1 | 1.7 | 1.0 | 15.3 ± 12.7 | 0.12 | 0.24 | 0.00 | 0.05 |

| j ((((tp,((((tl,ga),bo),st),bi)),lu),ca),out) | (A, C) | 0.4 | 1.8 | 1.3 | 1.6 | 1.1 | 1.7 | 0.8 | 17.1 ± 12.3 | 0.08 | 0.21 | 0.00 | 0.04 |

| i ((((tp,(((tl,(ga,bo)),st),bi)),ca),lu),out) | (-, A) | 0.6 | 2.2 | 1.4 | 1.1 | 1.3 | 1.7 | 1.2 | 19.9 ± 13.1 | 0.07 | 0.20 | 0.00 | 0.03 |

| d ((((tp,lu),((((tl,bo),ga),st),bi)),ca),out) | (A, B) | 0.8 | 1.7 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 0.6 | 1.8 | 1.0 | 20.2 ± 17.6 | 0.12 | 0.29 | 0.00 | 0.03 |

| m ((((tp,lu),((((tl,ga),bo),st),bi)),ca),out) | (A, C) | 1.1 | 1.6 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 0.6 | 1.8 | 0.9 | 21.8 ± 16.9 | 0.10 | 0.20 | 0.00 | 0.02 |

| e ((((tp,lu),ca),(((tl,(ga,bo)),st),bi)),out) | (-, A) | 1.4 | 1.7 | 1.3 | 0.6 | 0.0 | 1.9 | 1.6 | 26.7 ± 19.1 | 0.08 | 0.23 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| g (((tp,((((tl,(ga,bo)),st),bi),ca)),lu),out) | (-, A) | 1.4 | 2.2 | 1.2 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 1.6 | 1.0 | 27.1 ± 18.3 | 0.07 | 0.31 | 0.00 | 0.02 |

| n (((tp,(lu,((((tl,ga),bo),st),bi))),ca),out) | (A, C) | 1.1 | 1.9 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 1.8 | 1.1 | 30.4 ± 16.0 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

Topologies that are not significantly rejected (P-value > 0.05) by the Kishino-Hasegawa (KH) test are listed. P-values by the approximately unbiased (AU) test, the Bayesian posterior probability (BPP), and the bootstrap probability (BP) are also shown for each topology. The Δ ln Li ± σi values are shown for each protein. Abbreviations for species names are: tp, tetrapods; lu, lunfishes; tl, teleost fishes; bo, bowfin; ga, gar; st, sturgeon; bi, bichir; ca, cartilaginous fishes; out, outgroup. Corresponding hypotheses in Figure 1 and 2 are also shown; (A, B) at topology d, for example, indicates that topology d corresponds to Figure 1A and Figure 2B.

Statistical tests

Topologies a and b in Tables 1 and 2 differ considerably from other topologies in their bootstrap probabilities and P-values. These two topologies have approximately equal likelihood values in each of the totalml and concatenated alignment analyses, although the ML tree in concatenated alignment analysis is the second best tree in totalml analysis, and vice versa.

In addition to the bootstrap probability and the KH test, a test based on Bayesian posterior probability (BPP) has been carried out. The resulting BPP values are self-contradictory; topology a, which was the best topology in concatenated alignment analysis (Table 1), is significantly rejected in totalml analysis (Table 2; the BPP value was 0.005). Thus the BPP test might be too liberal, as already pointed out [27,28]. The approximately unbiased (AU) test has also been carried out for reference.

Focusing on some phylogenetic problems, the support values for each competing hypothesis were computed based on the intact bootstrap probability (BP) analysis (see Materials and Methods), the TREE-PUZZLE (TP) program [29] and the MRBAYES[30] program (Table 3). In addition, the RELL BP value, the BPP value and the P-values by the KH test and the AU test, which are based on concatenated alignment analysis described above, are also shown. The intact BP value is largely accordant to the RELL BP value, whereas low support values are observed in the TP method. This may be an artifact derived from the limited topology searches in the TP method, because the same result as shown in Table 1 was obtained, when the candidate topologies described above were subjected to the TREE-PUZZLE program with the 'user defined trees' option.

Table 3.

Tests of significance for conflicting phylogenetic hypotheses

| P-values | |||||||

| Hypotheses | intact BP | RELL BP | KH | AU | BPP | MRBAYES | TREE-PUZZLE |

| 1. Basal jawed vertebrate | |||||||

| A. Cartilaginous fishes | 0.93 | 0.88 | ML | ML | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.69 |

| B. Tetrapods | 0.00 | 0.01 | ≤ 0.03 | ≤ 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 2. Phylogenetic relationship among ray-finned fishes | |||||||

| A. ((Teleostei, (bowfin, gar)), Chondrostei) | 0.90 | 0.89 | ML | ML | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.34 |

| B. (((Teleostei, bowfin), gar), Chondrostei) | 0.06 | 0.07 | ≤ 0.11 | ≤ 0.21 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| C. (((Teleostei, gar), bowfin), Chondrostei) | 0.03 | 0.01 | ≤ 0.05 | ≤ 0.08 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| D. (Teleostei, ((bowfin, gar), Chondrostei)) | 0.01 | 0.01 | ≤ 0.03 | ≤ 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.37 |

| 3. Phylogenetic position of bichir | |||||||

| A. Bichir is the basal ray-finned fish | 0.99 | 0.99 | ML | ML | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.71 |

| B. Bichir and Chondrostei form a monophyletic group | 0.00 | 0.01 | ≤ 0.02 | ≤ 0.08 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.16 |

| 4. Phylogenetic relationship among tetrapods, lobe-finned fishes and ray-finned fishes | |||||||

| A. ((tetrapods, lobe-finned fishes), ray-finned fishes) | 0.55 | 0.52 | ML | ML | 0.89 | 0.93 | 0.37 |

| B. ((tetrapods, ray-finned fishes), lobe-finned fishes) | 0.40 | 0.39 | ≤ 0.42 | ≤ 0.81 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.51 |

Hypotheses 1 A and B and hypotheses 2 A-D correspond to those shown in Figure 1A and 1B and Figure 2A,2B,2C,2D, respectively. Hypotheses supported in this study are shown in bold letters. Two types of bootstrap probabilities (intact and RELL, see Materials and Methods for their differences), P-values by the Kishino-Hasegawa (KH) test and the approximately unbiased (AU) test, the Bayesian posterior probability (BPP) and support values by the MRBAYES and TREE-PUZZLE programs are shown.

Cartilaginous fishes have a basal position among jawed vertebrates

Cartilaginous fishes are thought to be ancestral to other jawed vertebrates in the traditional view (Figure 1A). In contrast, Rasmussen and Arnason [1,2] and Arnason et al. [3] pointed out another possibility that bony fishes are ancestral to cartilaginous fishes (Figure 1B). The present results strongly support the traditional view as shown in Figure 3 and Table 3. The bootstrap probabilities of the topologies having a basal position of cartilaginous fishes totaled 88.2% and 87.8% in concatenated alignment analysis and totalml analysis, respectively. The minimum log-likelihood difference between the ML tree and trees not supporting a basal split between cartilaginous fishes and remaining jawed vertebrates was 18.3 ± 13.1 (P-value = 0.09) and 15.3 ± 12.7 (P-value = 0.12), in concatenated alignment analysis and totalml analysis, respectively. The minimum log-likelihood difference between the ML tree and that supporting the bony fish origin of cartilaginous fishes was 123 ± 23.3 (P-value < 0.01) and 137 ± 29.6 (P-value < 0.01) in concatenated alignment analysis and totalml analysis, respectively, providing strong evidence against the hypothesis by Arnason's group [1-3]. When the lancelet (a distant outgroup) sequences are excluded from the analysis, the minimum log-likelihood difference between the ML tree and trees that support their hypothesis was 122 ± 25.9, still being statistically significant.

According to the phylogenetic analysis based on mitochondrial sequences, however, all topologies consistent with the present analysis are significantly rejected (P-value < 0.01). This controversial result may be due to the incompleteness of phylogenetic information retained in the mitochondrial sequences; the amino acid composition of mitochondrial DNA-coded proteins is highly biased to hydrophobic residues and thus multiple and reverse substitutions may occurs very frequently [4]. In addition, the evolutionary rates of mitochondrial sequences often differ greatly for different lineages; the mitochondrial sequences of most tetrapods evolve more rapidly than those of fishes [31,32]. These evolutionary features characteristic of mitochondrial sequences might result in the LBA artifact [23].

Did tetrapods originate from lobe-finned fishes?

Several molecular phylogenetic analyses were carried out to clarify the phylogenetic relationship among tetrapods, coelacanth and lungfishes, using ray-finned fishes [33-36] and/or cartilaginous fishes [5,9,37] as an outgroup. The validity of these two rootings needs to be confirmed with molecular evidence [2,5]. Although no coelacanth sequence is included, the present analysis provides a confirmation for the cartilaginous fish rooting. Ray-finned fishes, however, cannot be used as an outgroup, because it remains possible that tetrapods are more closely related to ray-finned fishes than to lobe-finned fishes (topology b in Tables 1 and 2).

Since bichir, the basal ray-finned fishes (see below), have a pair of lungs and fleshy pectoral fins [38], the common ancestor of bony fishes are likely to be somewhat like lobe-finned fishes. Thus it remains possible that tetrapods originated from such ancestral ray-finned fishes or from the common ancestor of ray-finned fishes and lobe-finned fishes. Recently reported fossil records suggest that the divergence of lungfish and tetrapods occurred at least as early as 417-412 Mya [39,40]. According to Kumar and Hedges [41] and Hedges [12], the divergence of ray-finned fishes and lobe-finned fishes was estimated to have occured at 450-400 Mya, which is simultaneous with or immediately before the divergence of lungfish and tetrapods. This is consistent with the present study suggesting the almost simultaneous divergence of tetrapods, lungfishes and ray-finned fishes.

Living holosteans form a natural group

The phylogenetic relationship among teleost fishes and holosteans comprising bowfin and gar is controversial [15]. Four different tree topologies (Figure 2A,2B,2C,2D) have been proposed to date from morphological and molecular data. According to a formerly accepted view, living ray-finned fishes are divided into three major groups (Figure 2A): Chondrostei (chondrosteans including sturgeons and paddlefishes), 'Holostei' (holosteans comprising bowfin and gar), and Teleostei (teleost fishes consisting all other living ray-finned fishes). 'Holostei' is, however, a term that has fallen into disuse in formal classifications. Instead, in the currently accepted view, holosteans are considered to be paraphyletic; bowfin is thought to be more closely related to teleost fishes than gar is [14,38], as shown in Figure 2B, and therefore ray-finned fishes are classified into two monophyletic groups: Chondrostei and Neopterygii (holosteans and teleost fishes). Another possibility that gar is closely related to teleost fishes (Figure 2C) was also proposed [42]. Furthermore, mitochondrial sequences suggest a distinct tree topology (Figure 2D), in which holosteans and chondrosteans form a monophyletic group [16].

In the present analysis, holosteans are inferred to form a monophyletic group that is the sister group to teleost fishes, as shown in Figure 3 and Table 3. The bootstrap probabilities for the holostean clade are 92.2% and 83.8% in concatenated alignment analysis and totalml analysis, respectively. The topologies not supporting the holostean clade are relatively small in P-values (≤ 0.12), as shown in Tables 1 and 2. This result is rather consistent with a formerly accepted view of vertebrate classification, but is inconsistent with the currently accepted view. The mitochondrial tree shown in Figure 2D was significantly rejected by the KH test, if its likelihood value was calculated using nuclear DNA-coded genes; its log-likelihood difference from the ML tree was 34.9 ± 18.0 (P-value = 0.03) and 42.3 ± 20.8 (P-value = 0.02) in concatenated alignment analysis and totalml analysis, respectively.

We also analyzed a mitochondrial data set and confirmed the monophyly of holosteans and chondrosteans. In contrast to the high support value (100%) by the MRBAYES program for this relationship, however, the RELL BP value was only 71%. The likelihood difference between topologies A and D of Figure 2 was 11.9 ± 13.3 (P-value = 0.18), which is not significant, as Inoue et al. [16] noted. Considering the Bayesian inference often results in erroneously high support values [28,43], the inconsistency between the present inference and that based on mitochondrial sequences might be caused by the artifact of the Bayesian inference.

Bichir is the basal ray-finned fish

The phylogenetic position of bichir has long been controversial as well, as it shares many characters with both lobe-finned fishes and ray-finned fishes [9,44]. Most morphologists currently place bichir to a basal position in ray-finned fishes [38,45], although it remains possible that bichir and chondrosteans form a monophyletic group [14]. Recently, Venkatesh et al. [9,46] found one molecular synapomorphy indicating that bichir is the basal ray-finned fish, under the assumption that cartilaginous fishes are basal in the jawed-vertebrate tree. Our result strongly confirms the result from molecular synapomorphies: bichir is placed at the deepest position in ray-finned fishes, and the bootstrap probabilities are 98.1% and 95.1% in concatenated alignment analysis and in totalml analysis, respectively, as shown in Figure 3 and Table 3. The alternative hypothesis that bichir and chondrosteans form a monophyletic group was not supported; its log-likelihood difference from the ML tree is 37.4 ± 18.5 (P-value = 0.02) and 33.3 ± 19.5 (P-value = 0.04) in concatenated alignment analysis and totalml analysis, respectively.

Chimaeras and other cartilaginous fishes form a monophyletic group

Some paleontologists have pointed out the possibility that chimaeras were derived from placoderms independently from other cartilaginous fishes (eg, [38]). To test this possibility, we have isolated the genes listed in Materials and methods, except for ALDb, from a plownose chimaera, Callorhinchus callorhynchus, and have inferred its phylogenetic position based on the concatenated alignment of 2,431 amino acid residues. The resulting tree significantly supported the monophyly of cartilaginous fishes including chimaeras (as shown by dash-dotted line in Figure 3) with the RELL bootstrap probability of 100%. Mitochondrial data also support this relationship [3].

Conclusions

Molecular phylogenetic analyses of jawed vertebrates based on mitochondrial sequences often result in confusing inferences which are obviously inconsistent with generally accepted trees. To obtain a robust tree of jawed vertebrates, we have cloned and sequenced seven nuclear DNA-coded genes from thirteen vertebrate species and have carried out phylogenetic analyses including thirteen jawed vertebrates from eight major groups and an outgroup (a cyclostome and a lancelet) based on the maximum likelihood method. We have shown that (i) cartilaginous fishes are basal to other jawed vertebrates. This is consistent with generally accepted view, but is inconsistent with mitochondrial trees. (ii) Living holosteans, comprising bowfin and gar, form a monophyletic group which is the sister group to teleost fishes. This is consistent with a formerly prevalent view of vertebrate classification, but inconsistent with both of the current morphology-based and mitochondrial sequence-based trees. (iii) The bichir is the basal ray-finned fish. (iv) Tetrapods and lungfish form a monophyletic cluster in the tree inferred from the concatenated alignment, being consistent with currently accepted view. It remains also possible that tetrapods are more closely related to ray-finned fishes than to lungfishes.

The present results are statistically solid and highly consistent with traditional views based on morphological and paleontological evidence. Comparing with trees inferred from mitochondrial sequences, which often provide obviously bizarre phylogeny, these nuclear DNA-coded genes probably have more accurate phylogenetic information. More intensive taxonomic sampling, particularly inclusion of coelacanth, would provide more solid inference for the origin of tetrapods and other phylogenetic problems currently discussed mainly based on mitochondrial sequences. An extended analysis including coelacanth sequences is in progress.

Materials and methods

Isolation and sequencing of cDNAs

We have carried out a phylogenetic analysis of jawed vertebrates based on seven nuclear DNA-coded genes from six ray-finned fishes, three tetrapods, two lobe-finned fishes, three cartilaginous fishes and an outgroup (a cyclostome and a lancelet). For plownose chimaera, only six gene sequences excluding ALDb sequence were available for analysis. The names and abbreviations of proteins used in the present analysis are as follows: ALDa, ALDb and ALDc, fructose-bisphosphate aldolase A, B and C, respectively; G6PD, glucose-6-phosphate 1-dehydrogenase; GAG, a trifunctional protein with glycinamide ribonucleotide synthetase (GARS)-aminoimidazole ribonucleotide synthetase (AIRS)-glycinamide ribonucleotide formyltransferase (GART); PGK, phosphoglycerate kinase; TPI, triosephosphate isomerase.

Species and tissues used for RNA extraction are as follows: Ambystoma mexicanum, axolotl (gill and tail); Lepidosiren paradoxa, South American lungfish (brain, liver, heart and muscle); Protopterus annectens, African lungfish (pectoral fin); Oryzias latipes, Japanese medaka (liver); Lepisosteus osseus, longnose gar (brain, liver and muscle); Amia calva, bowfin (caudal fin); Acipenser baerii, Siberian sturgeon (brain and liver); Polypterus ornatipinnis, bichir (brain, liver and muscle); Cephaloscyllium umbratile, swell shark (brain, liver and muscle); Potamotrygon motoro, freshwater stingray (brain and liver); Callorhinchus callorhynchus, plownose chimaera (embryo); Lethenteron reissneri, lamprey (larva); Eptatretus burgeri, inshore hagfish (liver); Branchiostoma belcheri, lancelet (whole body). Total RNAs were extracted using TRIZOL Reagent (GIBCO BRL). These total RNAs were reverse-transcribed to cDNAs using oligo(dT) primer with reverse transcriptase (SuperScript II, GIBCO BRL) and were used as templates for PCR amplification with Expand High-Fidelity PCR System (Roche Diagnostics). The sense and antisense degenerate primers of the seven proteins were designed from conserved amino acid residues of each gene as shown in Table 4. PCR amplification was carried out under annealing condition of 43–50°C with the sense and antisense primers. Nested PCR with a proper set of sense and antisense primers was carried out with primary PCR product, when needed.

Table 4.

Degenerate primers used for the cloning of cDNAs

| Target | Primer | Amino acid sequence | |

| ALDa-c | sense | 5'-CAGGATCCAARGGIATHYTIGCNGC-3' | GKGILAA |

| sense | 5'-GGCCGTCGTCGGNATHAARGTNGA-3' | VGIKVD | |

| antisense | 5'-CAGAATTCGTIACCATRTTIGGYTT-3' | KPNMVT | |

| antisense | 5'-GTGIACGCAICKCCAYTTNGCRAA-3' | FAKWRCV | |

| ALDc | antisense | 5'-CTCYTTYTTNCCNCCCCANGCYTT-3' | KAWGGKKE |

| ALDa,c | antisense | 5'-GGCTAGNGGNACNACNCCYTTRTC-3' | DKGVVPLA |

| G6PD | sense | 5'-CATAATGGGIGCIWSIGGNGAYYT-3' | IMGASGDL |

| sense | 5'-GTCAGCTACTGGNGAYYTNGCNAA-3' | ATGDLAK | |

| sense | 5'-GTCATCTTCGGIGCNWSNGGNGAY-3' | GASGD | |

| sense | 5'-GACCACTAYYTNGGNAARGARATG-3' | DHYLGKEM | |

| antisense | 5'-AGATGCAGGYTTYTCCATNGCNAC-3' | VAMEKPAS | |

| antisense | 5'-GTCGSWNCKNACRAARTGCATYTG-3' | QMHFVRSD | |

| GAG | sense | 5'-CAGTGGCGGIMGIGARCAYRC-3' | SGGREH(A/T) |

| sense | 5'-GATGCCNCCIGCNCARGAYC-3' | MPPAQDH | |

| sense | 5'-GAGTTYAAYTGYMGNTTYGG-3' | EFNCRFG | |

| antisense | 5'-CCGAANCKRCARTTRAAYTC-3' | EFNCRFG | |

| antisense | 5'-GTTRAAGGTNCKIGYCATYTC-3' | EM(A/T)RTFN | |

| antisense | 5'-GAAGCCTGCIARRTCRTAYTC-3' | EYDLAGF | |

| antisense | 5'-GTCRTTIACRCACATNGCNAC-3' | VAMCVND | |

| PGK | sense | 5'-CATCCGIGTNGAYTTYAAYGTNCC-3' | RVDFNVP |

| antisense | 5'-GAAGACACCNGGNGGNCCRTTCCA-3' | WNGPPGVF | |

| antisense | 5'-CTTGTCISWIACYTTNGCNCCNCC-3' | GGAKVSDK | |

| antisense | 5'-GTTCTCDATNARYTGDATYTTRTC-3' | DKIQLI | |

| TPI | sense | 5'-CCGGTACCAAYTGGAARATGAAYGG-3' | NWKMNG |

| antisense | 5'-ATGGATCCCCIACIARRAAICCRTC-3' | DGFLV | |

| antisense | 5'-GCCTATGGCCCANACNGGYTCRTA-3' | YEPVWAIG |

EcoRI, BamHI and KpnI restriction sites are underlined. Amino acid sequence used for designing each degenerate primer is also shown. Abbreviation for each protein name: ALDa, fructose-bisphosphate aldolase A; ALDb, fructose-bisphosphate aldolase B; ALDc, fructose-bisphosphate aldolase C; G6PD, glucose-6-phosphate 1-dehydrogenase; GAG, a trifunctional protein with glycinamide ribonucleotide synthetase (GARS)-aminoimidazole ribonucleotide synthetase (AIRS)-glycinamide ribonucleotide formyltransferase (GART); PGK, phosphoglycerate kinase; TPI, triosephosphate isomerase.

The PCR products were separated in 1.5% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide. Products of expected size were isolated as gel slices, purified using DNA purification kit (TOYOBO), and cloned into pT7Blue vector (Novagen). Then, Escherichia coli strain DH5α (TOYOBO) was transformed with a ligated vector. More than three independent clones were isolated for each gene and sequenced by dideoxy chain termination method using BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Kit (Applied Biosystems) and ABI PRISM 377 and 3100 DNA sequencers (Applied Biosystems).

The 3' ends of cDNAs were amplified using 3'RACE System for Rapid Amplification of cDNA Ends (GIBCO BRL). The amplified fragments were purified, subcloned and sequenced in the same way as above.

Sequence data

The following sequence data was taken from the DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank database: the seven gene sequences from human, mouse and Takifugu rubripes (fugu); ALD gene sequences from Eptatretus burgeri (inshore hagfish), Lethenteron japonicum (Japanese lamprey) and B. belcheri; TPI gene sequences from L. reissneri and B. belcheri. The DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank accession number of each sequence data is shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Sequence data used for the present analysis

DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank accession numbers of sequences used in the present analysis are shown, except for fugu sequences, for which Ensembl transcript IDs are shown. Abbreviation for each protein name: ALDa, fructose-bisphosphate aldolase A; ALDb, fructose-bisphosphate aldolase B; ALDc, fructose-bisphosphate aldolase C; G6PD, glucose-6-phosphate 1-dehydrogenase; GAG, a trifunctional protein with glycinamide ribonucleotide synthetase (GARS)-aminoimidazole ribonucleotide synthetase (AIRS)-glycinamide ribonucleotide formyltransferase (GART); PGK, phosphoglycerate kinase; TPI, triosephosphate isomerase. Taxonomic name for each species: Axolotl, Ambystoma mexicanum; South-American lungfish, Lepidosiren paradoxa; African lungfish, Protopterus annectens; Japanese medaka, Oryzias latipes; Fugu, Takifugu rubripes; Longnose gar, Lepisosteus osseus; Bowfin, Amia calva; Sturgeon, Acipenser baerii; Bichir, Polypterus ornatipinnis Swell shark, Cephaloscyllium umbratile; Freshwater stingray, Potamotrygon motoro; Plownose chimaera, Callorhinchus callorhynchus; Cyclostome, 1 Eptatretus burgeri, 2 Lethenteron japonicum, 3 Lethenteron reissneri (a hagfish sequence was used instead of lamprey sequence because of their monophyletic relationship [13,25,54]); Lancelet, Branchiostoma belcheri.

Phylogenetic tree inference

Multiple alignments of amino acid sequences were carried out by MAFFT[47], a multiple sequence alignment program recently developed by us, and manually inspected on the XCED sequence alignment editor.

Using the cyclostome and lancelet sequences as an outgroup, phylogenetic analyses have been carried out by GAMT[26], a genetic algorithm-based ML method, with the JTT-F model [48,49]. Heterogeneity of evolutionary rates among sites was modeled by a discrete Γ distribution [50] with the optimized shape parameter α for each protein. A limited number of candidate tree topologies were generated by the following procedure and subjected to the comparison of likelihood values and statistical tests.

For alignment constructed from each of the seven protein sequences and that of the concatenated sequences, the GAMT program [26] was applied. GAMT is a method for searching for the ML tree based on the genetic algorithm (GA), outputting the best tree as well as multiple alternative trees each of which has a likelihood value close to the best one. The outline of the procedure is as follows: (i) The initial population of tree topologies is generated by applying the NJ method [51] to alignments generated by the bootstrap resampling. (ii) The fitness value for the best tree in the population is set to a constant value Nw, that for the second best one is set to Nw-1, and so on. (iii) A new tree i is generated by applying either of two operators (mutation or crossover) to trees picked up from the current population according to their fitness values. (iv) If there is a tree j with Δ lnLj/σj > ΔlnLi/σi in the current population, tree i replaces tree j, where Δ lnLi(= lnLbest-lnLi) is the log-likelihood difference between tree i and the best tree in the current population, and σi is the standard deviation of Δ lnLi. (v) The procedure from steps (ii-iv) is repeated Ne times. Parameters used in the present analysis are as follows: Nw = 100 and Ne = 10,000.

This procedure was repeated for the seven different proteins and the concatenated alignment. The resulting topologies with Δ lnLi < σi from each of the seven proteins were selected as candidate ones. Additional topologies with σi ≤ Δ lnLi < 3 σi were also selected from the concatenated alignment. For the all candidate topologies selected, the log-likelihood values were computed from the seven protein sequence data sets, and totaled following the procedure of Kishino et al. [52] using the TOTALML program from the MOLPHY package [48]. This procedure is hereafter referred to as 'totalml' analysis. Another type of log-likelihood value was computed from the concatenated alignment for each candidate topology. This procedure is hereafter referred to as 'concatenated alignment' analysis.

Statistical tests

The following known statistical tests (i-vii) were carried out in the present analysis. (i) Kishino-Hasegawa (KH) test and (ii) approximately unbiased (AU) test were carried out using the CONSEL package [53]. (iii) Bayesian posterior probability (BPP) value of each of the candidate topologies was also computed using the CONSEL package [53]. (iv) Bootstrap probability value for a hypothesis was computed by applying the RELL (resampling of estimated log-likelihoods) approximation [52] to the candidate topologies and then totaling the bootstrap probabilities of the candidates supporting the hypothesis. This value is referred to as RELL BP value or simply BP value. (v) The MRBAYES program [30] was applied to the concatenate alignment. Default settings were used except for aamodel = jones, rates = gamma, ngen = 200,000 and burnin = 100. (vi) The TREE-PUZZLE program [29] was applied to the concatenate alignment. (vii) Intact bootstrap probability was also computed for the concatenated alignment. The calculation procedure is simple, but time-consuming; the ML tree was inferred by the GAMT program independently for each of the 100 alignments generated by bootstrap resampling, and the number of the ML trees supporting the hypothesis was counted. This value is referred to as intact BP value. The first four methods (i-iv), which are for testing given candidate topologies, were applied to both totalml and concatenated alignment analyses, whereas the last three methods (v-vii), each of which is for inferring a phylogenetic tree, were applied to the concatenated alignment without setting any candidate topologies.

Authors' contributions

K Kikugawa carried out the labwork and phylogenetic analysis. K Katoh carried out phylogenetic analysis and wrote the manuscript. S Kuraku and N Iwabe developed laboratory protocols, provided a part of sequence data, and supervised the labwork and phylogenetic analysis. H Sakurai and O Ishida carried out collection and preparation of plownose chimaera embryos. T Miyata designed the study and edited the manuscript.

List of abbreviations

ALDa, fructose-bisphosphate aldolase A; ALDb, fructose-bisphosphate aldolase B; ALDc, fructose-bisphosphate aldolase C; G6PD, glucose-6-phosphate 1-dehydrogenase; GAG, a trifunctional protein with glycinamide ribonucleotide synthetase (GARS)-aminoimidazole ribonucleotide synthetase (AIRS)-glycinamide ribonucleotide formyltransferase (GART); PGK, phosphoglycerate kinase; TPI, triosephosphate isomerase; LSU rRNA, large-subunit ribosomal RNA.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr K Kuma for discussion, and Ms K Shibamoto for technical assistance. This work was supported in part by Grants-in-Aid for Creative Scientific Research and COE Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan.

Contributor Information

Kanae Kikugawa, Email: kikugw@biophys.kyoto-u.ac.jp.

Kazutaka Katoh, Email: katoh@biophys.kyoto-u.ac.jp.

Shigehiro Kuraku, Email: venezia@cdb.riken.go.jp.

Hiroshi Sakurai, Email: sakurai@tzps.or.jp.

Osamu Ishida, Email: ishida@tzps.or.jp.

Naoyuki Iwabe, Email: iwabe@biophys.kyoto-u.ac.jp.

Takashi Miyata, Email: miyata@biophys.kyoto-u.ac.jp.

References

- Rasmussen AS, Arnason U. Phylogenetic studies of complete mitochondrial molecules place cartilaginous fishes within the tree of bony fishes. J Mol Evol. 1999;48:118–123. doi: 10.1007/pl00006439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen AS, Arnason U. Molecular studies suggest that cartilaginous fishes have a terminal position in the piscine tree. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:2177–2182. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.5.2177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnason U, Gullberg A, Janke A. Molecular phylogenetics of gnathostomous (jawed) fishes: old bones, new cartilage. Zool Scripta. 2001;30:249–249. doi: 10.1046/j.1463-6409.2001.00067.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Naylor GJP, Brown WM. Structural biology and phylogenetic estimation. Nature. 1997;388:527–528. doi: 10.1038/41460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y, Waddell PJ, Okada N, Hasegawa M. The complete mitochondrial sequence of the shark Mustelus manazo: evaluating rooting contradictions to living bony vertebrates. Mol Biol Evol. 1998;15:1637–1646. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zardoya R, Meyer A. Vertebrate phylogeny: limits of inference of mitochondrial genome and nuclear rDNA sequence data due to an adverse phylogenetic signal/noise ratio. In: Ahlberg PE, editor. In Major Events in Early Vertebrate Evolution. London: Taylor & Francis; 2001. pp. 135–155. [Google Scholar]

- Cotton JA, Page RD. Going nuclear: gene family evolution and vertebrate phylogeny reconciled. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2002;269:1555–1561. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2002.2074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera MC, Lake JA. Evidence that eukaryotes and eocyte prokaryotes are immediate relatives. Science. 1992;257:74–76. doi: 10.1126/science.1621096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesh B, Erdmann MV, Brenner S. Molecular synapomorphies resolve evolutionary relationships of extant jawed vertebrates. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:11382–11387. doi: 10.1073/pnas.201415598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimmick WW. Spliceosomal introns and fish phylogeny: a critical reanalysis. Copeia. 2001;2001:536–541. [Google Scholar]

- Martin A. The phylogenetic placement of chondrichthyes: inferences from analysis of multiple genes and implications for comparative studies. Genetica. 2001;111:349–357. doi: 10.1023/A:1013747532647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedges SB. Molecular evidence for the early history of living vertebrates. In: Ahlberg PE, editor. In Major Events in Early Vertebrate Evolution. London: Taylor & Francis; 2001. pp. 119–134. [Google Scholar]

- Takezaki N, Figueroa F, Zaleska-Rutczynska Z, Klein J. Molecular phylogeny of early vertebrates: monophyly of the agnathans as revealed by sequences of 35 genes. Mol Biol Evol. 2003;20:287–292. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msg040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson JS. Fish of the World. 3. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Arratia G. The sister-group of teleostei: consensus and disagreements. J Vertebr Paleontol. 2001;21:767–773. [Google Scholar]

- Inoue JG, Miya M, Tsukamoto K, Nishida M. Basal actinopterygian relationships: a mitogenomic perspective on the phylogeny of the 'ancient fish'. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2003;26:110–120. doi: 10.1016/S1055-7903(02)00331-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Normark BB, McCune AR, Harrison RG. Phylogenetic relationships of neopterygian fishes, inferred from mitochondrial sequences. Mol Biol Evol. 1991;8:819–834. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lê HL, Lecointre G, Perasso R. A 28s rRNA-based phylogeny of the gnathostomes: first steps in the analysis of conflict and congruence with morphologically based cladograms. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 1993;2:31–51. doi: 10.1006/mpev.1993.1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takezaki N, Gojobori T. Correct and incorrect vertebrate phylogenies obtained by the entire mitochondrial sequences. Mol Biol Evol. 1999;16:590–601. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwabe N, Kuma K, Nikoh N, Miyata T. Molecular clock for dating of divergence between animal phyla. Jpn J Genet. 1995;70:687–692. doi: 10.1266/jjg.70.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikoh N, Iwabe N, Kuma K, Ohno M, Sugiyama T, Watanabe Y, Yasui K, Shi-cui Z, Hori K, Shimura Y, Miyata T. An estimate of divergence time of parazoa and eumetazoa and that of cephalochordata and vertebrata by aldolase and triose phosphate isomerase clocks. J Mol Evol. 1997;45:97–106. doi: 10.1007/pl00006208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merritt TJ, Quattro JM. Evidence for a period of directional selection following gene duplication in a neurally expressed locus of triosephosphate isomerase. Genetics. 2001;159:689–697. doi: 10.1093/genetics/159.2.689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein J. Cases in which parsimony and compatibility methods will be positively misleading. Syst Zool. 1978;27:401–410. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang R, Yatsuki H, Kusakabe T, Iwabe N, Miyata T, Imai T, Yoshida M, Hori K. Structures of cDNAs encoding the muscle-type and non-muscle-type isozymes of lamprey fructose bisphosphate aldolases and the evolution of aldolase genes. J Biochem (Tokyo) 1995;117:545–553. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a124742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuraku S, Hoshiyama D, Katoh K, Suga H, Miyata T. Monophyly of lampreys and hagfishes supported by nuclear-coded genes. J Mol Evol. 1999;49:729–735. doi: 10.1007/pl00006595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh K, Kuma K, Miyata T. Genetic algorithm-based maximum-likelihood analysis for molecular phylogeny. J Mol Evol. 2001;53:477–484. doi: 10.1007/s002390010238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley T. Model misspecification and probabilistic tests of topology: evidence from empirical data sets. Syst Biol. 2001;51:509–523. doi: 10.1080/10635150290069922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki Y, Glazko GV, Nei M. Overcredibility of molecular phylogenies obtained by bayesian phylogenetics. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:16138–16143. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212646199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strimmer K, von Haeseler A. Quartet puzzling: a quartet maximum-likelihood method for reconstructing tree topologies. Mol Biol Evol. 1996;13:964–969. [Google Scholar]

- Huelsenbeck JP, Ronquist F. MrBayes: Bayesian inference of phylogenetic trees. Bioinformatics. 2001;17:754–755. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.8.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas WK, Beckenbach AT. Variation in salmonid mitochondrial: evolutionary constraints and mechanisms of substitution. J Mol Evol. 1989;29:233–245. doi: 10.1007/BF02100207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adachi J, Cao Y, Hasegawa M. Tempo and mode of mitochondrial evolution in vertebrates at the amino acid sequence level: rapid evolution in warm-blooded vertebrates. J Mol Evol. 1993;36:270–281. doi: 10.1007/BF00160483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer A, Wilson AC. Origin of tetrapods inferred from their mitochondrial affiliation to lungfish. J Mol Evol. 1990;31:359–364. doi: 10.1007/BF02106050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorr T, Kleinschmidt T, Fricke H. Close tetrapod relationships of the coelacanth latimeria indicated by haemoglobin sequences. Nature. 1991;351:394–397. doi: 10.1038/351394a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zardoya R, Cao Y, Hasegawa M, Meyer A. Searching for the closest living relative(s) of tetrapods through evolutionary analyses of mitochondrial and nuclear data. Mol Biol Evol. 1998;15:506–517. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zardoya R, Meyer A. Evolutionary relationships of the coelacanth, lungfishes, and tetrapods based on the 28s ribosomal gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:5449–5454. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.11.5449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tohyama Y, Ichimiya T, Kasama-Yoshida H, Cao Y, Hasegawa M, Kojima H, Tamai Y, Kurihara T. Phylogenetic relation of lungfish indicated by the amino acid sequence of myelin dm20. Mol Brain Res. 2000;80:256–259. doi: 10.1016/S0169-328X(00)00143-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romer AS, Persons TS. The Vertebrate Body. 6. New York: WB Saunders Co; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu M, Yu X, Ahlberg PE. A primitive sarcopterygian fish with an eyestalk. Nature. 2001;410:81–84. doi: 10.1038/35065078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu M, Yu X. A primitive fish close to the common ancestor of tetrapods and lungfish. Nature. 2002;418:767–770. doi: 10.1038/nature00871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Hedges SB. A molecular timescale for vertebrate evolution. Nature. 1998;392:917–920. doi: 10.1038/31927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen PE. The skull and pectoral girdle of the parasemionotid fish watsonulus eugnathoides from the early triassic sakamena group of madagascar, with comments on the relationships of the holostean fishes. J Vertebr Paleontol. 1984;4:481–499. [Google Scholar]

- Waddell PJ, Kishino H, Ota R. Very fast algorithms for evaluating the stability of ML and Bayesian phylogenetic trees from sequence data. Ser Workshop Genome Inform. 2002;13:82–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janvier P. Early Vertebrates. Oxford: Clarendon Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Grande L, Bemis WE. Interrelationships of Acipenseriformes, with comments on "Chondrostei". In: Stiassny MLJ, Parenti LR, Johnson GD, editor. In Interrelationships of Fishes. San Diego: Academic Press; 1996. pp. 85–115. [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesh B, Ning Y, Brenner S. Late changes in spliceosomal introns define clades in vertebrate evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:10267–10271. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.18.10267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh K, Misawa K, Kuma K, Miyata T. MAFFT: a novel method for rapid multiple sequence alignment based on fast fourier transform. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:3059–3066. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkf436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adachi J, Hasegawa M. In Computer Science Monographs. Vol. 28. Tokyo: Inst Stat Math; 1996. MOLPHY version 2.3: Programs for molecular phylogenetics based on maximum likelihood. [Google Scholar]

- Jones DT, Taylor WR, Thornton JM. The rapid generation of mutation data matrices from protein sequences. Comput Appl Biosci. 1992;8:275–282. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/8.3.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z. Maximum likelihood phylogenetic estimation from sequences with variable rates over sites: approximate methods. J Mol Evol. 1994;39:306–314. doi: 10.1007/BF00160154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1987;4:406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishino H, Miyata T, Hasegawa M. Maximum likelihood inference of protein phylogeny, and the origin of chloroplasts. J Mol Evol. 1990;31:151–160. [Google Scholar]

- Shimodaira H, Hasegawa M. CONSEL: for assessing the confidence of phylogenetic tree selection. Bioinformatics. 2001;17:1246–1247. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.12.1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stock DW, Whitt GS. Evidence from 18s ribosomal sequences that lampreys and hagfishes form a natural group. Science. 1992;257:787–789. doi: 10.1126/science.1496398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]