Abstract

Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinase (TIMPs) are critical for tissue remodeling during wound repair. Psychological stress has been found to impair wound healing in humans and animals. The objective of this study was to assess MMP and TIMP gene expression during stress-impaired healing. Female SKH-1 mice (n = 299) were divided into control and stress groups (13 h restraint/day for 3 days prior to and 5 days post-wounding). Two 3.5 mm cutaneous full-thickness wounds were placed on the dorsum of each mouse and wound measurements were performed daily. RTPCR for gene expression of MMP-2, MMP-8, MMP-9, TIMP-1 and TIMP-2 was performed at days 1, 3 and 5. Immunohistochemical analyses of the healed wounds were performed at days 15 and 28. As expected, wounds healed more slowly in restraint-stressed mice compared to controls. Stressed mice exhibited MMP-8 overexpression and lower TIMP-1 levels during healing, and poorer collagen organization once healed. MMP-8 overexpression may have stemmed from a higher level of neutrophils, observed in wound tissue on days 3 and 5. These findings implicate higher neutrophil numbers, MMP-8 overexpression, and TIMP-1 under-expression, as mechanisms that may compromise wound outcomes such as scarring under conditions of stress.

Keywords: Wound healing, Psychological stress, Mifepristone, RU486, Collagen, MMP, TIMP, Remodeling, Scarring

1. Introduction

Healing is an essential attribute for health and if impaired can affect the quality of life. The stress of academic examinations or caregiving for Alzheimer’s patients delayed healing by 40% and 24%, respectively (Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 1995; Marucha et al., 1998). Similarly, in a mouse model, restraint stress causes 27% delay in wound healing (Padgett et al., 1998).

Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) are transcriptionally induced by a number of inflammatory cytokines and growth factors (Mauviel et al., 1993). Stress is known to differentially regulate these same factors (Mercado et al., 2002b; Hawkley et al., 2007), and thereby may alter MMP expression in tissues. Specific to this, hernia surgical patients reporting higher worry about the operation had lower MMP-9 levels in wound fluid, as well as greater pain and slower recovery (Broadbent et al., 2003).

MMPs are involved in a number of functions during wound repair including removal of non-vital tissue, stimulation of keratinocyte migration, blood vessel growth, connective tissue remodeling, and regulation of growth factor activity (for review see (Malemud, 2006)). MMP-2 and MMP-9 play a role in remodeling extracellular matrix (ECM) and they are involved in final degradation of fibrillar collagen after initial cleavage by other collagenases (Aimes and Quigley, 1995; Okada et al., 1995). MMP-8, the predominant collagenase in normal healing wounds, mediates degradation of type I collagen, the principal type of collagen in wound tissue (Nwomeh et al., 1999). Tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs) are also important for normal wound healing and their expression is tightly regulated, both temporally and spatially, during tissue repair (Vaalamo et al., 1999). Hence, dysregulation of MMP-TIMP activity has been widely implicated in impaired healing (Saarialho- Kere et al., 1992; Wysocki et al., 1993; Malemud, 2006). TIMP-1 appears involved in re-epithelialization via stabilization of the basement membrane and by regulating stromal remodeling and angiogenesis of the wound bed (Vaalamo et al., 1999). TIMP-2 inhibits MMP activity and modulates angiogenesis by suppressing the proliferation of human endothelial cells (Madlener et al., 1998; Muller et al., 2008).

Chronic non-healing wounds have been long associated with an imbalance between MMPs and TIMPs (Bullen et al., 1995; Muller et al., 2008). In the present study, the effects of restraint stress on the expression of MMP-2, MMP-8, MMP-9, TIMP-1 and TIMP- 2 in mice were determined. In a smaller subset of animals, the association of MMPs with cutaneous wound healing following RU486 (mifepristone, a glucocorticoid (GC) receptor antagonist) administration was assessed.

2. Methods

2.1. Animals

Virus antibody free, female SKH-1 mice (n = 299), 5–6 weeks of age, housed 4–5/cage on a 12 h light/dark cycle, were obtained from Charles River, Inc (Wilmington, MA, USA). Experiments were carried out in a facility approved by the American Association for the Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC) and were approved by The Ohio State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

2.2. Restraint stress

As previously described (Padgett et al., 1998) for 3 cycles prior to and 5 cycles after wounding, mice were restrained overnight in well-ventilated, loose-fitting 50 ml centrifuge tubes. Restraint stress (RST) started at 18:00 h (dark onset) and ended at 07:00 h. Control mice (FWD) were deprived of food and water during the same time period but were free to roam their cages. A separate group of RST mice received daily subcutaneous injections of RU486 (RST + RU486).

2.3. RU486 treatment

Starting one day prior to beginning of restraint, mice were injected daily with 25 mg/kg of type II GC receptor antagonist RU486. The subcutaneous injections were made 4 h prior to restraint, distal to the site of wounding. Control animals were injected with vehicle (polyethylene glycol 400, Sigma). Control animals were not injected with RU486 as it has been demonstrated that glucocorticoid receptor blockade does not alter healing rates in non-restrained mice (Padgett et al., 1998; personal observations).

2.4. Wounding

Placement and morphometric measurement of the wounds were performed as previously described (Eijkelkamp et al., 2007). Using a biopsy punch (Premier Medical Products, King of Prussia, PA, USA), each mouse had two circular 3.5-mm cutaneous fullthickness wounds, placed just behind the shoulder blades to prevent the licking of wounds. Digital photographs of the wounds were obtained immediately after wounding and daily thereafter. Measurements (blinded) of the wound area were standardized to a 3.5 mm diameter circle (template) and expressed as a ratio to the wound area at the time of wounding.

2.5. Quantitative real-time PCR

At days 1, 3 and 5 post-wounding different subsets of mice were anesthetized and wounds were harvested using a 6 mm biopsy punch. Tissue biopsies were flash-frozen in 1 ml of TRIzol (Life Technologies, Rockville, MA) and stored at −80 °C. Total RNA was extracted from the tissues and mRNA selected. Poly(A) selected RNA was reverse transcribed to create cDNA as previously described (Horan et al., 2005).

Primers and probes were obtained from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA). Gene expression was standardized to G3PDH gene expression in the respective samples. ΔRn/Ct determined from the fluorescence measures of each probe was used to quantitate the relative amount of target cDNA.

2.6. Immunohistochemistry

On days 15 and 28, healed wounds were assessed for collagen deposition and pattern using Picrosirius red staining. Paraffin sections were placed in xylene for 10 min and progressively rehydrated with ethanol/double distilled water. Rehydrated sections were treated with 0.2% aqueous phosphomolybdic acid, rinsed and stained with 0.1% Sirius red in saturated picric acid. These were washed in hydrochloric acid, washed in 70% ethanol and dehydrated before being mounted on slides.

2.7. Neutrophils

A follow-up experiment assessed whether neutrophil numbers were altered by stress or stress + RU486 treatment. This involved additional mice that were euthanized at 6 h and days 1 through 7 after wounding for myeloperoxidase (MPO) extraction, as described by (Zhou et al., 1996). Units of MPO per wound were determined by regression analysis using a standard curve.

2.8. Statistical analyses

Univariate analysis of variance (ANOVA) with repeated measures was used to determine the effects of time and stress on wound healing, gene expression, and MPO content. Post-hoc tests were conducted with Scheffe for unequal samples and Tukey for equally-sized samples. Day was treated as a within-subjects variable, stress and treatment (RU486) as between-subjects variables. α= .05 determined significance. Data were analyzed with SPSS 19.0 (SPSS Inc. Chicago, IL, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Wound healing

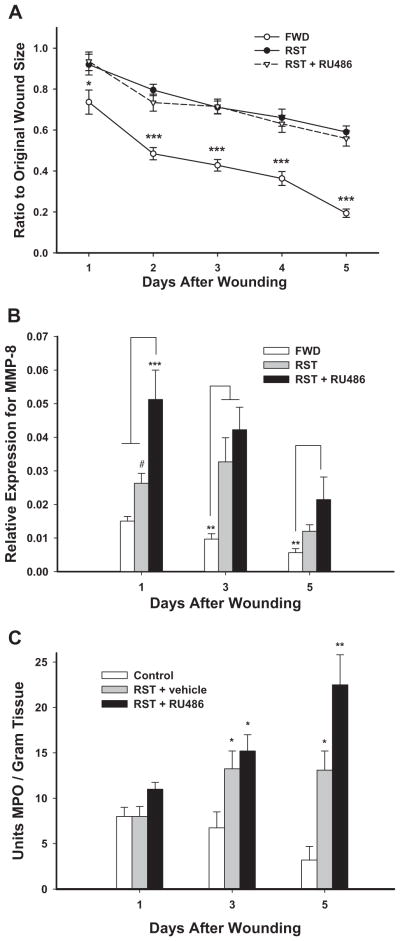

Non-stressed animals (FWD) showed quicker healing on days 1–5 (p < .05 or better) compared to either stressed group (RST or RST + RU486). There were no significant differences in wound healing between the RST and RST + RU486 groups (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

(A) Wound size ratios over 5 days post-wounding. (B) Relative gene expression for MMP-8 in wounded tissue. (C) Neutrophil levels during dermal healing. In (C) excised wound tissue was subjected to myeloperoxidase (MPO) extraction, MPO was quantified by a colorimetric assay and expressed as units of MPO/gram of wound tissue. Data represent mean ± SEM. *p < .05 compared to FWD. **p < 0.05 compared to FWD and RST/VEH, ***p < .001, #p = .092.

3.2. Matrix metalloproteinases

For MMP-2, a main effect of Day was observed (F(2,190) = 17.33, p < .001); all groups exhibited increased gene expression across days with the highest levels observed on day 5. No effects of stress or treatment occurred (not shown). Analyses of MMP-8 gene expression found main effects of Day (F(2,190) = 13.20, p < .001) and Stress (F(2,190) = 27.45, p < .001). MMP-8 gene expression was highest on day 1 and lowest by day 5 (Fig. 1B). Overall, RST groups had significantly higher MMP-8 gene expression than controls. Expression of MMP-8 appeared to peak on day 1 for the controls and day 3 for the RST group; at day 3 RST mice exhibited significantly higher MMP-8 expression compared to controls. Higher MMP-8 expression occurred in the RST + RU486 mice on all test days compared to controls; this was also higher compared to RST mice on day 1 (p < .001). For MMP-9 there was a main effect of Day (F(2,190)=14.52, p < .001). Higher expression of MMP-9 was seen on day 1 compared to days 3 and 5. No effects of stress or treatment occurred (not shown).

3.3. Tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinase

TIMP-1, which is known to bind most activated MMPs (Madlener et al., 1998), showed no differences between FWD and RST groups across days 1 and 3. However, on day 5, the stressed animals had lower TIMP-1 gene expression (p = .04). TIMP-2 rose significantly across days (F(2,114) = 52.17, p < .001) but did not show any difference in expression between the stress and control groups. Gene expression for TIMPs was not assessed in RU486 treated mice.

3.4. Collagen

In separate mice, healed wounds were assessed for collagen fiber orientation using Picrosirius red staining. A different pattern was clearly visible between the stress and control groups at day 15 (Fig. 2A and B). This difference was even clearer at day 28 (Fig. 2C–D). Fibers were more clearly arranged and symmetrical in the non-stress group. The photographs are representative of their respective groups.

Fig. 2.

Picrosirius red staining for collagen deposition (shown at 40 × magnification): (A) FWD at 2 weeks. (B) RST at 2 weeks. (C) FWD at 4 weeks. (D) RST at 4 weeks. In the non-stress group, fibers were more clearly arranged and symmetrical both at 2 and 4 week assessments, demonstrating superior collagen organization in healed tissue.

3.5. Neutrophils

In a follow-up experiment, the effects of RU486 on wound MPO in mice subjected to RST were quantified at days 1, 3 and 5 postwounding. No differences were found between groups at day 1. At days 3 and 5 RST mice had an increase in wound MPO levels as compared to FWD mice (p < 0.05). The present study shows that RST + RU486 mice also had higher levels of MPO than FWD mice on days 3 and 5. Furthermore, at day 5, RST + RU486 mice had higher wound MPO levels than RST mice (p < 0.05) (Fig. 1C).

4. Discussion

This is the first study to characterize the relation between stress-impaired cutaneous wound healing, MMP and TIMP gene expression during healing, and the quality of healed tissues. In addition to delayed healing, there was an overexpression of MMP-8 in stressed animals on days 1 and 3, and a persistence of neutrophils on days 3 and 5. This dysregulation likely contributed to the poorer quality of healed tissue during stress, as evidenced by poor collagen fibril organization in healed wounds.

MMP-8 mRNA levels were highest on day 1, and dropped across test days. Interestingly, these levels were highest in the stressed mice. TIMP-1 was unchanging across days in control mice; however, restraint-stressed mice exhibited lower expression on day 5 post-wounding, suggesting TIMP-1 dysregulation also occurred. These effects may be due, in part, to stress-altered inflammatory responses, demonstrated previously in this model (Padgett et al., 1998; Gajendrareddy et al., 2005; Eijkelkamp et al., 2007). MMP- 8 (neutrophil collagenase) is produced primarily by neutrophils and is released at sites of inflammation (Tester et al., 2007). Here we confirmed neutrophil numbers were higher on days 3 and 5 in stressed mice compared to controls (Tymen et al., 2012). This protracted pattern of neutrophil activity likely accounts for the observed overexpression of MMP-8 with stress. Conversely, expression levels for MMP-2 and MMP-9, which are not strongly associated with neutrophil activity, were not altered by stress in this study.

Although not investigated here, the mechanisms observed in stress-impaired healing of acute wounds appear strikingly similar to non-healing chronic wounds. These include altered expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines and growth factors (Mercado et al., 2002b), impaired bacterial clearance (Rojas et al., 2002), a disruption of oxygen balance (Gajendrareddy et al., 2005), and now an altered pattern of MMP and TIMP expression, especially MMP-8.

MMP-8 is the predominate collagenase in both acute wounds and in chronic non-healing ulcers (Nwomeh et al., 1999). Chronic non-healing ulcers are characterized by excessive tissue loss due to reduced collagen, and an imbalance between levels of MMPs and TIMPs (Wysocki and Grinnell, 1990; Bullen et al., 1995; Muller et al., 2008), with increased MMP-8 and reduced TIMP-1 levels occurring compared to normally healing surgical wounds (Bullen et al., 1995; Yager et al., 1996; Nwomeh et al., 1999; Muller et al., 2008; Wysocki et al., 1993). Thus, it is likely that MMP-8 overexpression is involved in the pathogenesis of non-healing wounds, and such effects may be further amplified by the lowering of TIMP-1. Importantly, such wounds exhibit excessive collagenolysis as opposed to normally healing dermal wounds (Nwomeh et al., 1999).

The ultimate measure of the quality of healing is scarring, which is defined by disorganized collagen often resulting in reduced tensile strength. The patterns of wound healing and collagen organization clearly differed among our stress and control groups. Non-stressed mice showed superior collagen organization in healed tissue both at 2 and 4 week assessments. Given that a similar disorganization of collagen was seen in stressed mice at both these time points, this appears to not be a temporal delay in the healing process, but rather a deficient final outcome of wound healing. This outcome is indicative of more extensive scarring as a result of stress during wound healing. To our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate that stress relates to poor collagen architecture upon healing. This likely equates to lower tensile strength in the healed tissue, as past studies have associated less organized collagen fibers with poorer tensile strength (Gosain and DiPietro, 2004; Guo and Dipietro, 2010). In separate studies, we have noted weaker tensile strength of healed wounds in restraint stressed mice compared to controls (personal observations). Glucocorticoid administration, which models stress, has similarly been shown to reduce the breaking strength of healed wounds (Beck et al., 1993). Importantly, MMP-8 overexpression has been related to lower type I collagen deposition in the wound bed and poor wound tensile strength (Danielsen et al., 2011).

RU486 is a known GC receptor antagonist and, as such, should theoretically ameliorate the negative effects of stress on wound healing. Indeed, RU486 has been shown to normalize components of stress-impaired wound healing such as reducing bacterial load (Rojas et al., 2002) and normalizing early inflammatory responses in wounded tissue (IL-1βmRNA levels) (Mercado et al., 2002a). The present study found that RU486 did not improve wound closure in stressed mice, but actually resulted in the persistence of neutrophils (MPO activity) in the wound. This may account for the reduction of bacterial load by RU486. Clearly, persistence of neutrophils tends to increase tissue damage and can affect the later outcomes of healing.

This study suggests that MMP-8 overexpression and TIMP-1 under-expression may be related not only with the delayed healing of chronic wounds, as has been shown in other studies (Nwomeh et al., 1999; Pirila et al., 2007), but also with stress-impaired healing of acute wounds. These alterations in gene expression may have stemmed from high neutrophil levels persisting in the wound site. Overt qualitative differences in collagen fibril orientation between wounds of stressed and non-stressed mice suggest a permanent negative outcome of the overexpression of MMP-8 on wound healing.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIH grants P20-GM078426 and R01-DE017686.

References

- Aimes RT, Quigley JP. Matrix metalloproteinase-2 is an interstitial collagenase. Inhibitor-free enzyme catalyzes the cleavage of collagen fibrils and soluble native type I collagen generating the specific 3/4- and 1/4-length fragments. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:5872–5876. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.11.5872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck LS, DeGuzman L, Lee WP, Xu Y, Siegel MW, Amento EP. One systemic administration of transforming growth factor-beta 1 reverses age- or glucocorticoid-impaired wound healing. J Clin Invest. 1993;92:2841–2849. doi: 10.1172/JCI116904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broadbent E, Petrie KJ, Alley PG, Booth RJ. Psychological stress impairs early wound repair following surgery. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:865–869. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000088589.92699.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullen EC, Longaker MT, Updike DL, Benton R, Ladin D, Hou Z, Howard EW. Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-1 is decreased and activated gelatinases are increased in chronic wounds. J Invest Dermatol. 1995;104:236–240. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12612786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danielsen PL, Holst AV, Maltesen HR, Bassi MR, Holst PJ, Heinemeier KM, Olsen J, Danielsen CC, Poulsen SS, Jorgensen LN, Agren MS. Matrix metalloproteinase-8 overexpression prevents proper tissue repair. Surgery. 2011;150:897–906. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2011.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eijkelkamp N, Engeland CG, Gajendrareddy PK, Marucha PT. Restraint stress impairs early wound healing in mice via alpha-adrenergic but not betaadrenergic receptors. Brain Behav Immun. 2007;21:409–412. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2006.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gajendrareddy PK, Sen CK, Horan MP, Marucha PT. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy ameliorates stress-impaired dermal wound healing. Brain Behav Immun. 2005;19:217–222. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosain A, DiPietro LA. Aging and wound healing. World J Surg. 2004;28:321–326. doi: 10.1007/s00268-003-7397-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo S, Dipietro LA. Factors affecting wound healing. J Dent Res. 2010;89:219–229. doi: 10.1177/0022034509359125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkley LC, Bosch JA, Engeland CG, Cacioppo JT, Marucha PT. Loneliness, dysphoria, stress, and immunity a role for cytokines. In: Plotnikoff NP, Faith RE, Murgo AJ, editors. Cytokines: Stress and Immunity. CRC Press; Boca Raton, Florida: 2007. pp. 67–85. [Google Scholar]

- Horan MP, Quan N, Subramanian SV, Strauch AR, Gajendrareddy PK, Marucha PT. Impaired wound contraction and delayed myofibroblast differentiation in restraint-stressed mice. Brain Behav Immun. 2005;19:207–216. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2004.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Marucha PT, Malarkey WB, Mercado AM, Glaser R. Slowing of wound healing by psychological stress. Lancet. 1995;346:1194–1196. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)92899-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madlener M, Parks WC, Werner S. Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and their physiological inhibitors (TIMPs) are differentially expressed during excisional skin wound repair. Exp Cell Res. 1998;242:201–210. doi: 10.1006/excr.1998.4049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malemud CJ. Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) in health and disease: an overview. Front Biosci. 2006;11:1696–1701. doi: 10.2741/1915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marucha PT, Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Favagehi M. Mucosal wound healing is impaired by examination stress. Psychosom Med. 1998;60:362–365. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199805000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauviel A, Qiu Chen Y, Dong W, Evans CH, Uitto J. Transcriptional interactions of transforming growth-factor-beta with pro-inflammatory cytokines. Curr Biol. 1993;3:822–831. doi: 10.1016/0960-9822(93)90216-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercado AM, Padgett DA, Sheridan JF, Marucha PT. Altered kinetics of IL-1 alpha, IL-1 beta, and KGF-1 gene expression in early wounds of restrained mice. Brain Behav Immun. 2002a;16:150–162. doi: 10.1006/brbi.2001.0623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercado AM, Quan N, Padgett DA, Sheridan JF, Marucha PT. Restraint stress alters the expression of interleukin-1 and keratinocyte growth factor at the wound site: an in situ hybridization study. J Neuroimmunol. 2002b;129:74–83. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(02)00174-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller M, Trocme C, Lardy B, Morel F, Halimi S, Benhamou PY. Matrix metalloproteinases and diabetic foot ulcers: the ratio of MMP-1 to TIMP-1 is a predictor of wound healing. Diabet Med. 2008;25:419–426. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2008.02414.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nwomeh BC, Liang HX, Cohen IK, Yager DR. MMP-8 is the predominant collagenase in healing wounds and nonhealing ulcers. J Surg Res. 1999;81:189–195. doi: 10.1006/jsre.1998.5495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada Y, Naka K, Kawamura K, Matsumoto T, Nakanishi I, Fujimoto N, Sato H, Seiki M. Localization of matrix metalloproteinase 9 (92-kilodalton gelatinase/type IV collagenase = gelatinase B) in osteoclasts: implications for bone resorption. Lab Invest. 1995;72:311–322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padgett DA, Marucha PT, Sheridan JF. Restraint stress slows cutaneous wound healing in mice. Brain Behav Immun. 1998;12:64–73. doi: 10.1006/brbi.1997.0512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirila E, Korpi JT, Korkiamaki T, Jahkola T, Gutierrez-Fernandez A, Lopez-Otin C, Saarialho-Kere U, Salo T, Sorsa T. Collagenase-2 (MMP-8) and matrilysin-2 (MMP-26) expression in human wounds of different etiologies. Wound Repair Regen. 2007;15:47–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2006.00184.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas IG, Padgett DA, Sheridan JF, Marucha PT. Stress-induced susceptibility to bacterial infection during cutaneous wound healing. Brain Behav Immun. 2002;16:74–84. doi: 10.1006/brbi.2000.0619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saarialho-Kere UK, Chang ES, Welgus HG, Parks WC. Distinct localization of collagenase and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases expression in wound healing associated with ulcerative pyogenic granuloma. J Clin Invest. 1992;90:1952–1957. doi: 10.1172/JCI116073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tester AM, Cox JH, Connor AR, Starr AE, Dean RA, Puente XS, Lopez-Otin C, Overall CM. LPS responsiveness and neutrophil chemotaxis in vivo require PMN MMP-8 activity. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e312. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tymen SD, Rojas IG, Zhou X, Fang ZJ, Zhao Y, Marucha PT. Restraint stress alters neutrophil and macrophage phenotypes during wound healing. Brain Behav Immun. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2012.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaalamo M, Leivo T, Saarialho-Kere U. Differential expression of tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMP-1, -2, -3, and -4) in normal and aberrant wound healing. Hum Pathol. 1999;30:795–802. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(99)90140-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wysocki AB, Grinnell F. Fibronectin profiles in normal and chronic wound fluid. Lab Invest. 1990;63:825–831. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wysocki AB, Staiano-Coico L, Grinnell F. Wound fluid from chronic leg ulcers contains elevated levels of metalloproteinases MMP-2 and MMP-9. J Invest Dermatol. 1993;101:64–68. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12359590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yager DR, Zhang LY, Liang HX, Diegelmann RF, Cohen IK. Wound fluids from human pressure ulcers contain elevated matrix metalloproteinase levels and activity compared to surgical wound fluids. J Invest Dermatol. 1996;107:743– 748. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12365637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L, Pope BL, Chourmouzis E, Fung-Leung WP, Lau CY. Tepoxalin blocks neutrophil migration into cutaneous inflammatory sites by inhibiting Mac-1 and E-selectin expression. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:120–129. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]