Abstract

We report the identification of two peptides from Salmonella OmpC porin that can bind to major histocompatibility complex class I Kb molecules and are targets of cytotoxic T lymphocytes from Salmonella-infected mice. These peptides are conserved in gram-negative bacterial porins and are the first Salmonella porin-specific epitopes described for possible CD8+-T-cell elimination of infected cells.

Some of the most-studied protective immunogens of Salmonella are the outer membrane proteins (OMPs) called porins. Vaccination with purified porins can protect mice against the challenge of virulent Salmonella strains (4, 5, 6). In these protection processes, antiporin antibodies and T-cell-mediated immunity are required, and these T cells have been described as being Th2 type with predominant interleukin-4 and immunoglobulin G1 production (1, 2, 10, 11, 19). The role of CD8+ T cells during Salmonella infection is unclear but has gained interest because humans and mice immunized with attenuated Salmonella strains can generate a CD8+-T-cell response (3, 8, 15, 18). Also, the generation of major histocompatibility complex class I (MHC-I) molecule-restricted peptides from infected cells is not well characterized. We previously described that macrophages infected with Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium and activated with gamma interferon (IFN-γ) can secrete peptides that stabilize Kb molecules on the surface of RMA-S cells (9). Lo et al. have described an MHC class Ib-restricted response during infection with virulent Salmonella (7), and Pasetti et al. found an Ld-restricted response after intranasal administration with attenuated Salmonella strains (14).

In the present study, we searched for MHC-I epitopes from Salmonella OmpC porin, one of the two components of the porin preparation used in vaccine trials (5).

Kb binding peptide search and chemical synthesis.

In order to identify CD8+-T-cell epitopes derived from Salmonella serovar Typhimurium OmpC porin, we searched the sequence for eight-amino-acid-long peptides with the anchor amino acid motif described for peptides that bind to Kb molecules. The first analysis of peptides was done with the ProPred-I program (http://www.imtech.res.in/raghava/propred1/index.html), which screens for MHC-I binding peptides that can be generated by proteosome cleavage of the original protein (17). Four peptides from the serovar Typhimurium OmpC (gi 7428872) sequence were displayed by this analysis: 132-RNTDFFGL, 73-TRVAFAGL, 343-NTDDIVAL, and 159-ENTNGRSL. A second analysis of the OmpC sequence was done with the Parker HLA peptide motif search program (http://bimas.dcrt.nih.gov/molbio/hla_bind/), which estimates the half time of disassociation of an MHC molecule containing the predicted peptides (13). According to these two criteria, the peptides 132-RNTDFFGL (OmpC-132) and 73-TRVAFAGL (OmpC-73) had the highest chances to be natural Kb epitopes and so were chosen for further analysis. Peptides were synthesized by solid phase by using an ABI 430A automated synthesizer (Applied Biosystems Inc., Foster City, Calif.) and purified to >90% by reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography with a C18 column (Millipore, Bedford, Mass.).

Peptide binding assays and flow cytometry.

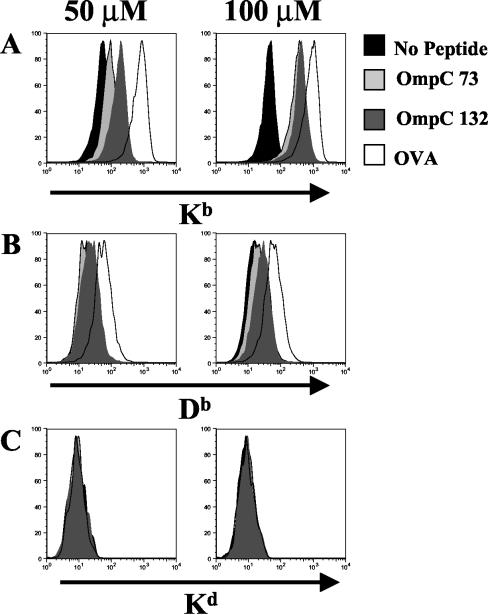

To test the binding of OmpC peptides to Kb molecules, the murine TAP 2 (transporter associated with antigen processing type 2)-deficient RMA-S cell line was cultured with 50 and 100 μM concentrations of each peptide for 6 to 8 h at 37°C. Kb binding of ovalbumin amino acids 257 to 264 (SIINFEKL peptide; OVA257-264) was used as a reference for positive peptide binding. Following extensive washes with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), cells were independently surface stained with purified monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) against Kb (Y3 [12]), Db (28-14-8S; ATCC HB-27), and Kd (SF1-1.1.1; ATCC HB-159) at 4°C. After two washes with PBS, counterstaining with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibody (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) was performed under the same conditions. A total of 104 RMA-S cells for each treatment was analyzed by flow cytometry on a FACSort (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, Calif.). Figure 1A shows the Kb profiles for RMA-S cells loaded with the predicted Salmonella OmpC peptides, and as expected OmpC-132 and OmpC-73 can bind to Kb molecules and stabilize alpha chains on the surfaces of RMA-S cells in a dose-dependent manner (a 3.8-fold increase in the mean fluorescence [mf] with 100 μM OmpC-73 and a 2.1-fold increase in the mf with 100 μM OmpC-132). OmpC peptide binding was Kb specific because high-dose OmpC peptides did not stabilize Db molecules (the mf values were 16.26 in the sample without peptide, 21.19 in the sample with OmpC-73, and 25.84 in the sample with OmpC-132). Although this result was clear for the OmpC peptides, the OVA257-264 peptide showed some binding to Db (mf, 62.73) when RMA-S cells were cultured with a 100 μM dose of peptide (Fig. 1B). In all cases, absence of staining was observed with the isotype control antibody against Kd (Fig. 1C).

FIG. 1.

Salmonella OmpC peptides bind specifically to Kb molecules. RMA-S cells were cultured with 50 and 100 μM concentrations of OmpC-73, OmpC-132, and OVA257-264 (OVA) peptides for 6 h, and then MHC-I molecules were surface stained and analyzed with a fluorescence-activated cell sorter. The results for anti-Kb MAb (A), anti-Db MAb (B), and anti-Kd MAb (C) are shown. Data shown are representative of three reproducible independent experiments.

Can these OmpC peptides elicit a CTL response after immunization?

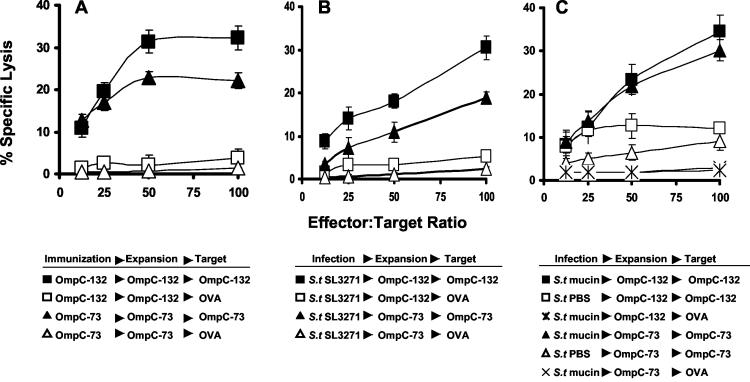

To test whether the OmpC peptides can elicit a cytotoxic T-lymphocyte (CTL) response in vivo, we immunized C57BL/6J mice with an emulsion of incomplete Freund’s adjuvant containing 100 μg of each peptide, which was applied subcutaneously at the base of the tail. This regimen was repeated three times at intervals of 1 week. At day 31, the mice were sacrificed for spleen removal and in vitro stimulation with the peptides. Briefly, splenocytes were cultured in 10% fetal calf serum-supplemented Dulbecco minimal essential medium and a 50 μM concentration of the corresponding peptide. Cells surviving after 5 days of culture were tested for cytolytic activity against 51Cr-labeled RMA-S cells loaded with peptide, as reported previously (20, 23). In Fig. 2A, a representative experiment is shown in which CTLs from OmpC-73- and OmpC-132-primed mice specifically kill RMA-S cells loaded with the corresponding peptide but not OVA257-264-loaded cells, indicating that the CTL activity observed was not due to another type of cell such as NK cells. It is worthwhile to mention that OmpC peptides bind and stabilize primarily to Kb and not to Db (Fig. 1A and B) molecules on RMA-S cells. Therefore, CTLs from Salmonella-infected mice recognize these epitopes only in a Kb-restricted manner on this cell line. In addition, OmpC-132 induced a stronger CTL response than the one derived from OmpC-73 immunization (P of <0.002 for effector-to-target cell ratios greater than 25:1), which correlates with their levels of peptide binding to RMA-S cells shown in Fig. 1. This finding confirms that C57BL/6J mice can generate a Kb-restricted CTL response against OmpC-73 and OmpC-132 peptides.

FIG. 2.

Cytotoxic response against Salmonella OmpC peptides. (A) C57BL/6 mice were immunized with OmpC-73 or OmpC-132 peptides. After 4 weeks, splenocytes were stimulated in vitro with the indicated peptide (expansion), and an assay of cytotoxic activity against RMA-S cells loaded with peptide (target) was performed. (B) Mice were orally infected with serovar Typhimurium SL3261 (S.t SL3261), and after 6 weeks splenocytes were tested as described for panel A. (C) Mice received an intraperitoneal load of serovar Typhi given in 5% mucin or in PBS (S.t mucin or S.t PBS), and splenocytes from both groups of mice were tested as described for panel A. All curves show the mean percentages of specific lysis at different effector-to-target cell ratios for triplicate wells; the bars indicate standard deviations. In all cases, results for a representative experiment out of three experiments with similar results are shown. Comparisons of cytotoxicity levels were performed by Student's t test with SigmaStat software (version 9.0; SPSS Science Software Products, Chicago, Ill.). P values of <0.05 were considered significant. OVA, OVA257-264 peptide.

Is the OmpC-specific CTL response present after Salmonella invasion?

C57BL/6J is an Itys mouse strain that cannot resist infection with virulent Salmonella serovar Typhimurium. To overcome this problem and evaluate the natural course of disease, we infected C57BL/6J mice orally with 106 PFU of attenuated aroA−/− Salmonella serovar Typhimurium SL3261. This protocol elicits a specific immune response for bacterial clearance in mice (21). After 6 weeks, mouse spleens were harvested, stimulated with peptides, and evaluated for specific CTL activity as described above. Mice given a Salmonella serovar Typhimurium dose that self-limits its replications after invasion can generate specific CTLs against OmpC-132 and OmpC-73 (Fig. 2B).

Based on the known homology of the Salmonella serovar Typhimurium OmpC sequence with other OMPs of gram-negative bacteria, we searched for OmpC-132 and OmpC-73 epitopes in the protein family of porins (Table 1). All Salmonella strains share the exact sequence for OmpC-73 and OmpC-132 in the OmpC porin. Interestingly, other strains and different porins share similar peptides with the anchor residues for binding to Kb molecules. Normally, S. enterica serovar Typhi does not cause systemic disease in mice. Therefore, to further confirm that the invasion of Salmonella into macrophages was required to generate the CTL response, we used mucin to apply serovar Typhi to the peritoneum of C57BL/6J mice (16). For this reason, 5,000 PFU of serovar Typhi 9,12,Vi:d in 5% mucin was administered, and control mice received the same bacterial dose in PBS. Six weeks later, splenocytes were screened for peptide CTL activity as described above. As shown in Fig. 2C, only mice that received serovar Typhi and mucin were able to generate a CTL response against OmpC peptide-loaded RMA-S cells (P of <0.02 for effector-to-target cell ratios greater than 50:1). Thus, Salmonella needs to colonize macrophages in order to generate a CTL response against porin peptides. This result also suggests that infected macrophages contribute to the generation of MHC-I peptides; further investigation will clarify the contribution of other antigen-presenting cells (dendritic cells and B cells) to the presentation of Salmonella antigens (22, 24, 25).

TABLE 1.

OmpC predicted epitopes in gram-negative bacterial OMPs

| GenBank accession no.a | Protein | Bacterial origin of proteinb | Similarity toc:

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OmpC-73 (TRVAFAGL) | OmpC-132 (RNTDFFGL) | |||

| 16761195 | OmpC | Serovar Typhimurium | + | + |

| 47797 | OmpC | Serovar Typhi | + | + |

| 8953564 | OmpC | Serovar Minnesota | + | + |

| 19743624 | OmpC | Serovar Dublin | + | + |

| 19743622 | OmpC | Serovar Gallinarum | + | + |

| 26248604 | OmpC | Escherichia coli | + | + |

| 24113600 | Omp1b | Shigella flexneri | + | RNSDFFGL |

| 16760442 | OmpS | Serovar Typhi | TRLAFAGL | + |

| 3273514 | OmpN | Escherichia coli | TRLAFAGL | + |

| 16764916 | OmpD | Serovar Typhimurium | TRLAFAGL | + |

| 16764875 | OmpC2 | Yersinia pestis | TRLGFAGL | + |

| 151149831 | OmpK36 | Klebsiella pneumonie | TRLAFAGL | RNSDFFGL |

GenBank, National Center for Biotechnology Information.

All serovars are those of Salmonella enterica.

+, identity to OmpC peptide. Amino acids shown in bold type are those that differ from the sequence in parentheses at top of column.

Further analysis of a specific CTL response directed against OmpC peptides will clarify the participation of CD8+ T cells in the elimination of infected cells, as well as some unanswered questions on the processing and presentation of Salmonella antigens.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by research grant 3595P-M9608 from the Mexican Council of Science and Technology (CONACyT). A.D.-Q. and N.M.-O. were recipients of a National Council of Science and Technology scholarship.

Y3 hybridoma was a kind gift of G. Hammerling, German Cancer Research Center, DKFZ, Heidelberg, Germany.

Editor: V. J. DiRita

REFERENCES

- 1.Cookson, B. T., and M. Bevan. 1997. Identification of a natural T cell epitope presented by Salmonella-infected macrophages and recognized by T cells from orally immunized mice. J. Immunol. 158:4310-4319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Galdiero, M., L. De Martino, A. Marcatili, I. Nuzzo, M. Vitiello, and G. Cipollaro de l'Ero. 1998. Th1 and Th2 cell involvement in immune response to Salmonella typhimurium porins. Immunology 94:5-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gonzalez, C. R., F. R. Noriega, S. Huerta, A. Santiago, M. Vega, J. Paniagua, V. Ortiz-Navarrete, A. Isibasi, and M. M. Levine. 1998. Immunogenicity of a Salmonella typhi CVD 908 candidate vaccine strain expressing the major surface protein gp63 of Leishmania mexicana mexicana. Vaccine 16:1043-1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Isibasi, A., V. Ortiz, M. Vargas, J. Paniagua, C. González, J. Moreno, and J. Kumate. 1988. Protection against Salmonella typhi infection in mice after immunization with outer membrane proteins isolated from Salmonella typhi 9,12,d,Vi. Infect. Immun. 56:2953-2959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Isibasi, A., V. Ortiz-Navarrete, J. Paniagua, R. Pelayo, C. R. Gonzalez, J. A. Garcia, and J. Kumate. 1992. Active protection of mice against Salmonella typhi by immunization with strain-specific porins. Vaccine 10:811-813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuusi, N., M. Nurminen, H. Saxen, M. Valtonen, and P. H. Mäkelä. 1979. Immunization with major outer membrane proteins in experimental salmonellosis of mice. Infect. Immun. 25:857-862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lo, W. F., H. Ong, E. S. Metcalf, and M. J. Soloski. 1999. T cell responses to gram-negative intracellular bacterial pathogens: a role for CD8+ T cells in immunity to Salmonella infection and the involvement of MHC class Ib molecules. J. Immunol. 162:5398-5406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lundin, B. S., C. Johansson, and A.-M. Svennerholm. 2002. Oral immunization with a Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi vaccine induces specific circulating mucosa-homing CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in humans. Infect. Immun. 70:5622-5627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martin-Orozco, N., A. Isibasi, and V. Ortiz-Navarrete. 2001. Macrophages present exogenous antigens by class I major histocompatibility complex molecules via a secretory pathway as a consequence of interferon-gamma activation. Immunology 103:41-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matsui, K., and T. Arai. 1989. Protective immunity induced by porin in experimental mouse salmonellosis. Microbiol. Immunol. 33:699-708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matsui, K., and T. Arai. 1989. Specificity of Salmonella porin as an eliciting antigen for cell-mediated immunity (CMI) reaction in murine salmonellosis. Microbiol. Immunol. 33:1063-1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ozato, K., and D. H. Sachs. 1981. Monoclonal antibodies to mouse MHC antigens. III. Hybridoma antibodies reacting to antigens of the H-2b haplotype reveal genetic control of isotype expression. J. Immunol. 126:317-321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parker, K. C., M. A. Bednarek, and J. E. Coligan. 1994. Scheme for ranking potential HLA-A2 binding peptides based on independent binding of individual peptide side-chains. J. Immunol. 152:163-175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pasetti, M. F., R. Salerno-Gonçalves, and M. B. Sztein. 2002. Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi live vector vaccines delivered intranasally elicit regional and systemic specific CD8+ major histocompatibility class I-restricted cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Infect. Immun. 70:4009-4018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Salerno-Goncalves, R., M. F. Pasetti, and M. B. Sztein. 2002. Characterization of CD8(+) effector T cell responses in volunteers immunized with Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi strain Ty21a typhoid vaccine. J. Immunol. 169:2196-2203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sein, J., V. Cachicas, M. I. Becker, and A. E. De Ioannes. 1993. Mucin allows survival of Salmonella typhi within mouse peritoneal macrophages. Biol. Res. 26:371-379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singh, H., and G. P. Raghava. 2003. ProPred1: prediction of promiscuous MHC class-I binding sites. Bioinformatics 19:1009-1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sztein, M. B., M. K. Tanner, Y. Polotsky, J. M. Orenstein, and M. M. Levine. 1995. Cytotoxic T lymphocytes after oral immunization with attenuated vaccine strains of Salmonella typhi in humans. J. Immunol. 155:3987-3993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thatte, J., S. Rath, and V. Bal. 1993. Immunization with live versus killed Salmonella typhimurium leads to the generation of an IFN-gamma-dominant versus an IL-4-dominant immune response. Int. Immunol. 5:1431-1436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Townsend, A., C. Ohlen, J. Bastin, H. G. Ljunggren, L. Foster, and K. Karre. 1989. Association of class I major histocompatibility heavy and light chains induced by viral peptides. Nature 340:443-448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.VanCott, J. L., S. N. Chatfield, M. Roberts, D. M. Hone, E. L. Hohmann, D. W. Pascual, M. Yamamoto, H. Kiyono, and J. R. McGhee. 1998. Regulation of host immune responses by modification of Salmonella virulence genes. Nat. Med. 4:1247-1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wick, M. J. 2002. The role of dendritic cells during Salmonella infection. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 14:437-443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wunderlich, J., and G. Shearer. 1997. Chromium-release assay for measuring CTL activity, p. 3.11.4-3.11.7. In J. E. Coligan, A. M. Kruisbeek, D. H. Margulies, E. M. Shevach, and W. Strober (ed.), Current protocols in immunology, vol. 1. John Wiley and Sons, New York, N.Y. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yrlid, U., M. Svensson, A. Håkansson, B. J. Chambers, H.-G. Ljunggren, and M. J. Wick. 2001. In vivo activation of dendritic cells and T cells during Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium infection. Infect. Immun. 69:5726-5735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yrlid, U., and M. J. Wick. 2002. Antigen presentation capacity and cytokine production by murine splenic dendritic cell subsets upon Salmonella encounter. J. Immunol. 169:108-116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]