Abstract

The virulence of a Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv sigE mutant was studied in immunodeficient and immunocompetent mice. The mutant was strongly attenuated in both animal models and induced formation of granulomas with different characteristics than those induced by the wild-type strain.

During infection, bacteria often face different environments which result from the site in which the pathogen resides as well as activation of the host's immune response. To be successful, a pathogen must be able to adapt quickly to these differing milieus. Most bacterial adaptive mechanisms are based on the regulation of gene expression, which consequently plays a very important role in bacterial pathogenesis (13).

Sigma factors play a major role in the regulation of bacterial gene expression. These proteins are interchangeable RNA polymerase subunits that are responsible for promoter recognition. Bacteria usually have a principal sigma factor, usually constitutively expressed, which is responsible for the transcription of essential housekeeping genes, and a number of alternative sigma factors that are transcriptionally and/or posttranslationally activated in response to specific environmental signals (14). The Mycobacterium tuberculosis genome encodes 13 putative sigma factors, 10 of which belong to the extra cytoplasmic function (ECF) family (4, 6). In previous work, our investigators studied the variation of σ factor gene expression in response to different environmental stresses and found that sigB and sigE were strongly induced after exposure to detergent-induced surface stress. The same two genes, together with sigH, were also induced after heat shock and after exposure to the thiol-specific oxidizing agent diamide (8, 9). Our investigators recently characterized two M. tuberculosis mutants lacking the ECF σ factors σE and σH. These mutants were sensitive to various environmental stresses; moreover, the sigE mutant showed a decreased ability to grow inside macrophages. Using DNA microarray technology, we have studied the σE and σH regulons and have identified several genes that are under direct or indirect control of these σ factors (9, 10). Interestingly, it has been recently reported that the M. tuberculosis sigE regulon is activated after phagocytosis (12).

σA, σF, and the ECF σ factor σH have a role in M. tuberculosis virulence, as shown in animal models of infection. A Mycobacterium bovis mutant with a mutated sigA was attenuated for virulence in guinea pigs (5), while an M. tuberculosis sigF strain was shown to be attenuated in immunocompetent mice (3). M. tuberculosis mutants lacking sigH produced a reduced immunopathology in infected animals (7), despite the observation that the growth kinetics in their organs were similar to that of the wild-type (wt) strain (7, 9).

In the experiments described in this communication, we have studied the M. tuberculosis sigE mutant ST28 (10) in two different mouse models of infection: immunocompetent BALB/c mice and severe combined immunodeficient (SCID) mice, which lack functional B and T cells. Specific-pathogen-free BALB/c mice were obtained from Charles River (Calco, Como, Italy). CB-17 SCID mice were purchased from Iffa Credo (Lyon, France). Male mice, aged 6 to 7 weeks, were used throughout the study. The animals were bred and maintained under barrier conditions and fed sterilized chow and water ad libitum. Mice were infected intravenously with 0.2-ml aliquots of mycobacterial suspensions containing approximately 105 CFU.

Evaluation of virulence in SCID mice.

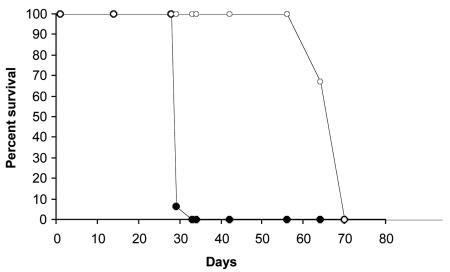

Twenty-two animals per group were maintained until they became moribund and had to be euthanized. All the SCID mice infected with M. tuberculosis H37Rv died in the first 33 days of the infection, while those infected with the mutant ST28 survived until 70 days after the infection (Fig. 1), clearly showing that the mutant is attenuated for virulence in this animal model.

FIG. 1.

Time-to-death analysis in SCID mice after intravenous infection with H37Rv (filled circles) and with the sigE mutant strain (empty circles).

Bacterial growth in BALB/c mice.

Three groups of 16 mice were each infected intravenously with the sigE mutant, the complemented strain, or the wt parental strain. On days 1, 21, 65, and 129 postinfection mice were killed and the numbers of CFU in the lungs, spleen, and liver were determined. Organs were aseptically removed and homogenized in Middlebrook 7H9 broth (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.). To enumerate CFU, 0.5-ml aliquots of 10-fold serial dilutions of homogenates were plated onto Middlebrook 7H10 agar medium (Difco) and colonies were counted after 3 weeks of incubation at 37°C. Small pieces of each organ were collected at 21 and 129 days and used for histological analysis.

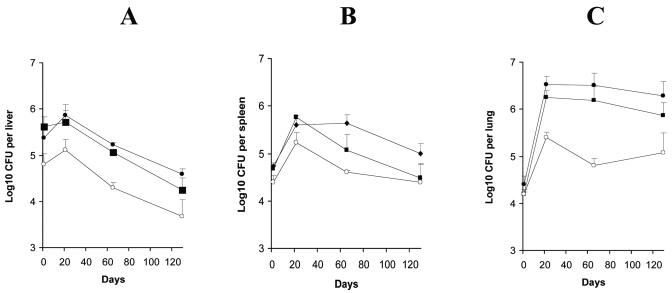

In the lungs, the numbers of H37Rv CFU increased by more than 2 log10 in the first 21 days followed by a plateau on days 65 and 129 (Fig. 2C); in the liver (Fig. 2A), after a slight increase up to day 21, the number of CFU decreased by more than 1 log10 by day 129; in the spleen (Fig. 2B), the number of CFU increased approximately 1 log10 in the first 21 days and then remained constant until day 65 and finally decreased approximately 0.7 log10 by day 129. The sigE mutant multiplied in the lungs up to day 21, even though the final bacterial load was about 1 log10 lower than that reached by the wt strain. Then the number of CFU decreased about 0.6 log10 by day 65 and remained relatively constant up to day 129 (Fig. 2C). In the liver, the number of CFU on day 1 was about 0.5 log10 lower than that of H37Rv, but the infection followed the same kinetics as H37Rv (Fig. 2A). In the spleen, the number of CFU increased by 0.8 log10 up to day 21 and then started to decrease (Fig. 2B). The growth of the complemented strain was similar to that of H37Rv in lung and liver. In the spleen, after the first increase, the clearance of the complemented strain was faster than that of the wt strain. The significance of this observation is not clear.

FIG. 2.

Growth rate of H37Rv (filled circles), the sigE mutant strain (empty circles), and the complemented mutant (filled squares) in livers (A), spleens (B), and lungs (C) of BALB/c mice.

Histopathological analysis.

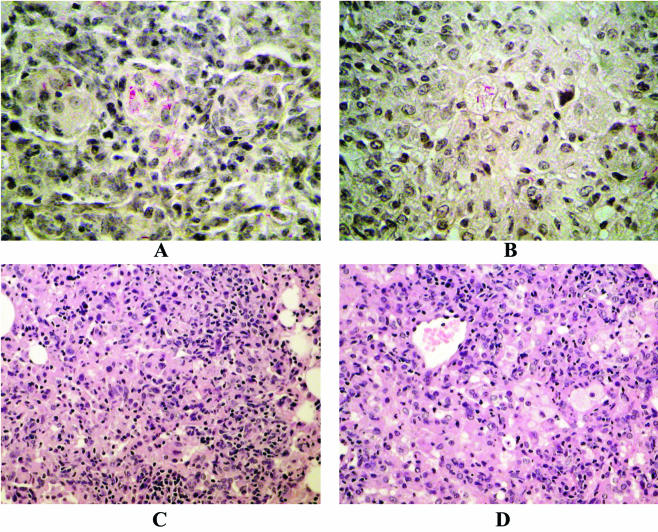

Specimens of the infected lung and liver were fixed in buffered formalin, routinely processed, and finally embedded in paraffin. Sections were stained with hematoxylin-eosin and by the Ziehl-Neelsen stain method. Epithelioid granulomas containing acid-fast bacilli were constantly observed in all the infected organs but with some differences: in H37Rv-infected lungs, granulomas were clearly evident as coalescences of small nodular aggregates of macrophages that showed a tendency to fuse and form giant cells; peripherally, small lymphocytes were present. Macrophages contained numerous acid-fast bacilli in their cytoplasm. No necrosis or fibrous reaction was observed (Fig. 3A and C). In the lungs infected with the mutant strain, epithelioid granulomas were less evident and lacked sharp outlines that faced the normal tissues. They consisted of central macrophages with peripherally located lymphocytes and contained acid-fast bacilli in their cytoplasm; some of them showed foamy transformation of the cytoplasm. Necrosis and fibrous reaction were also not evident in these samples and, in general, there were fewer lymphocytes (Fig. 3B and D).

FIG. 3.

Histopathological analysis of BALB/c mouse lungs after 21 days of infection with M. tuberculosis H37Rv (A and C) or the sigE mutant strain (B and D). Stains: Ziehl-Neelsen stain (A and B); hematoxylin stain (C and D).

Bacilli were not very numerous and were randomly dispersed not only in the central zone of the granulomatous region but were also outside. From our data it is clear that the sigE mutant is attenuated in both animal models. SCID mice infected with the mutant strain survived longer than those infected with the wt strain, supporting the hypothesis that σE is important for resistance to innate defenses.

In the BALB/c infections, the number of CFU of the mutant strain recovered from the mouse organs at day 1 was lower than the number of CFU recovered from wt- and complemented strain-infected animals, despite the fact that the number of CFU in the initial inocula of the three strains was comparable (data not shown). This was particularly evident in the liver (Fig. 2A), where the number of CFU of the mutant strain at day 1 was lower by about 0.6 log10 than that of wt and complemented strains. This suggests either a different distribution of this strain in the organs after intravenous infection or a higher rate of bacterial killing immediately after the infection. Differences in the clumping of the mutant bacteria relative to that of the wt could interfere with the bacterial enumeration and/or organ distribution; however, past studies with the sigE mutant strain have not noted increased clumping relative to the wt (reference 10 and unpublished results). σE is involved in the response to surface stress, and many of the genes under its transcriptional control encode surface proteins and enzymes involved in fatty acid biosynthesis and degradation (10). For this reason, the sigE mutant surface could have surface properties different from those of the wt strain.

Of particular interest is the finding that the structure of the lung granulomas induced by the mutant strain is slightly different from that induced by the wt. The absence of giant cells and the presence of fewer lymphocytes in the granulomas induced by the mutant strain suggest a lower level of inflammation. However, the presence in the same granuloma of infected macrophages with foamy transformation of the cytoplasm suggests a certain level of cellular damage and degeneration which was absent in granulomas induced by the wt strain.

During the reviewing process of this paper, Ando et al. (1) published the results of a similar study. In their experiments, the authors showed that experimental infection of mice with an M. tuberculosis sigE mutant resulted in delayed time to death. However, in contrast with our data, the ability of the mutant to grow in the lungs was the same as that of the wt strain. This difference with our results could be due to several reasons. First of all, we used M. tuberculosis H37Rv while the other authors used strain CDC1551; this latter strain was recently shown to be less virulent than H37Rv in an animal model (2). Also, the mouse strains were different: we used BALB/C mice, while the other authors used the C3H/HeJ inbred strain. The former are more resistant to M. tuberculosis than the latter (11). Finally, the route of infection was different: we used intravenous injection, while the other authors used aerosol infection.

In spite of these differences, the conclusions from both groups are complementary in that they show that σE plays an important role in M. tuberculosis pathogenesis in both immunocompetent and immunocompromised mice. Our data further suggest that the sigE mutant attenuation could be due not only to its reduced ability to adapt to the intracellular environment (10), but also from a decreased capacity of this strain to interfere with the immune system. Currently, experiments designed to identify genes controlled by σE that play a role in the disease process are in progress.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Istituto Superiore di Sanità, Progetto Nazionale AIDS no. 50D.20 (awarded to R.M.) and grant no. 2071/RI (awarded to L.F.); by MIUR, PRIN 2001 no. 2001053855 and PRIN 2002 no. 2002067349 (awarded to R.M.); and by National Institutes of Health grant HL 64544 (awarded to I.S.).

Editor: S. H. E. Kaufmann

REFERENCES

- 1.Ando, M., T. Yoshimatsu, C. Ko, P. J. Converse, and W. R. Bishai. 2003. Deletion of Mycobacterium tuberculosis sigma factor E results in delayed time to death with bacterial persistence in the lungs of aerosol-infected mice. Infect. Immun. 71:7170-7172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bishai, W. R., A. M. Dannenberg, Jr., N. Parrish, R. Ruiz, P. Chen, B. C. Zook, W. Johnson, J. W. Boles, and M. L. Pitt. 1999. Virulence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis CDC1551 and H37Rv in rabbits evaluated by Lurie's pulmonary tubercle count method. Infect. Immun. 67:4931-4934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen, P., R. E. Ruiz, Q. Li, R. F. Silver, and W. R. Bishai. 2000. Construction and characterization of a Mycobacterium tuberculosis mutant lacking the alternate sigma factor gene, sigF. Infect. Immun. 68:5575-5580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cole, S. T., R. Brosch, J. Parkhill, T. Garnier, C. Churcher, D. Harris, S. V. Gordon, K. Eiglmeier, S. Gass, C. E. Barry III, F. Tekaia, K. Badcock, D. Basham, D. Brown, T. Chillingworth, R. Connor, R. Davies, K. Devlin, T. Feltwell, S. Gentles, N. Hamlin, S. Holroyd, T. Hornsby, K. Jagles, B. G. Barrel, et al. 1998. Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete sequence. Nature 393:537-544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Collins, D. M., R. P. Kawakami, G. W. de Lisle, L. Pascopella, B. R. Bloom, and W. R. Jacobs, Jr. 1995. Mutation of the principal sigma factor causes loss of virulence in a strain of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:8036-8040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gomez, J. E., J. M. Chen, and W. R. Bishai. 1997. Sigma factors of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Tuber. Lung Dis. 78:175-183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaushal, D., B. J. Schroeder, S. Tyagi, T. Yoshimatsu, C. Scott, C. Ko, L. Carpenter, J. Mehrotra, Y. C. Manabe, R. D. Fleischmann, and W. R. Bishai. 2002. Reduced immunopathology and mortality despite tissue persistence in a Mycobacterium tuberculosis mutant lacking alternative σ factor, SigH. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:8330-8335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manganelli, R., E. Dubnau, S. Tyagi, F. R. Kramer, and I. Smith. 1999. Differential expression of 10 sigma factor genes in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol. Microbiol. 31:715-724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Manganelli, R., M. I. Voskuil, G. K. Schoolnik, E. Dubnau, M. Gomez, and I. Smith. 2002. Role of the extracytoplasmic-function σ factor σH in Mycobacterium tuberculosis global gene expression. Mol. Microbiol. 45:365-374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Manganelli, R., M. I. Voskuil, G. K. Schoolnik, and I. Smith. 2001. The Mycobacterium tuberculosis ECF sigma factor σE: role in global gene expression and survival in macrophages. Mol. Microbiol. 41:423-437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Medina, E., and R. J. North. 1998. Resistance ranking of some common inbred mice strains to Mycobacterium tuberculosis and relationship to major histocompatibility complex haplotype and Nramp1 genotype. Immunology 93:270-274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schnappinger, D., S. Erth, M. I. Voskuil, Y. Liu, J. A. Mangan, I. M. Monahan, G. Dolganov, B. Efron, P. D. Butcher, C. Nathan, and G. K. Schoolnik. 2003. Transcriptional adaptation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis within macrophages: insights into the phagosomal environment. J. Exp. Med. 198:693-704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith, I. 2003. Mycobacterium tuberculosis pathogenesis and molecular determinants of virulence. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 16:463-496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wösten, M. M. 1998. Eubacterial sigma-factors. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 22:127-150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]