Abstract

Background & Aims

IL28B single nucleotide polymorphisms are strongly associated with spontaneous HCV clearance and treatment response in non-transplant populations. A DDX58 single nucleotide polymorphism is associated with the antiviral response of innate lymphocytes. We aimed to evaluate the associations of donor and recipient IL28B (rs12979860 and rs8099917) and DDX58 (rs10813831) genotypes with severity of HCV recurrence after liver transplantation.

Methods

In a case-control study of 523 liver transplantation recipients with HCV, we matched severe with mild recurrent HCV based on 2-year clinical and histologic follow-up. A total 440 liver transplantation recipients (severe, n=235; mild, n=205) with recipient DNA and 225 (severe, n=123; mild, n=102) with both recipient and donor DNA were analyzed.

Results

IL28B [rs12979860, non-CC (vs.CC) and rs8099917, non-TT (vs.TT)] in the recipient-only analysis had higher risk of severe recurrent HCV [OR 1.57 and 1.58, p<0.05]. However, for the 225 with donor and recipient DNA, IL28B rs12979860 CC (vs. non-CC) and rs8099917 TT (vs.non-TT) and DDX58 rs10813831 non-GG (vs. GG) was associated with more (not less) severe recurrent HCV. The greatest risk of severe recurrent HCV was for rs12979860 CC donors in non-CC recipients (OR 7.02, p<0.001,vs. non-CC donor/recipient) and for rs8099917 TT donors in non-TT recipients (OR 5.78, p=0.001, vs. non-TT donor/recipient). These associations persisted after controlling for donor age, donor race and donor risk index.

Conclusions

IL28B and DDX58 single nucleotide polymorphisms that are favorable when present in the non-transplant setting or in the recipient are unfavorable when present in a donor liver graft.

Keywords: liver transplant, donor recipient matching, hepatitis C recurrence, IL28B, gene polymorphisms, clinical outcomes

Introduction

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is the leading indication for liver transplantation (LT) in the North America and Europe. Recurrent HCV in the liver graft is universal when HCV viremia is present at the time of LT. After LT, HCV infection progresses more rapidly to cirrhosis than in non-transplant patients who are not on immunosuppressive agents[1-3]. Unfortunately, newly available HCV treatment regimens are poorly tolerated and highly morbid in decompensated cirrhotic patients awaiting LT, and even more so after LT[4-7]. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) near the IL28B gene, encoding interferon- 3, are strongly associated with spontaneous HCV clearance[8, 9] and HCV treatment responses[10-12] in non-transplant populations[13]. Another common non-synonymous SNP in the DDX58 gene is associated with the antiviral response of innate lymphocytes (predominantly dendritic cells) to HCV infection[14-16].

In the LT recipient there are two genetic profiles, that of the donor and that of the recipient, which may influence the natural history and treatment response of HCV after LT. The relevance of IL28B polymorphisms (rs12979860 or rs8099917) to the severity of HCV recurrence and outcome after LT has been only incompletely characterized in five small single-center studies that included both donor and recipient DNA analysis[17-21]. In the largest of these studies an unfavorable genotype (rs12979860 TT) in the recipient was associated with more aggressive recurrent HCV, whereas a favorable genotype (rs12979860 CC) in the donor or recipient was associated with higher response rates to HCV treatment[17]. Another recent study examining the influence of IL28B rs12979860 also found that donor CC was unfavorable (higher risk for recurrent cirrhosis, need for retransplantation or death) whereas recipient CC was favorable (less likely to have advanced fibrosis, lower ALT and lower viral load) yet both donor and recipient CC were associated with increased likelihood of achieving a sustained viral response to HCV treatment[22]. Here, in our current study, we have evaluated the associations and interactions of donor and recipient IL28B (rs12979860 and rs8099917) and DDX58 (rs10813831) SNP genotypes with severity of HCV recurrence in LT recipients using a case-control design.

Patients and Methods

Detailed review of all adult (> 17 years old) patients who underwent LT for HCV at three medical centers (University of Colorado Denver, Baylor University Medical Center, and Oregon Health and Sciences University/Portland VA Medical Center) in the United States from 1998 to 2008 identified 523 LT recipients who met a priori definitions for either severe or mild recurrent HCV after LT. The immunosuppression protocols at these three mature liver transplant centers underwent no substantive changes across transplant eras and consisted principally of a calcineurin inhibitor (cyclosporine or tacrolimus) or sirolimus and either mycopenolate mofetil or mycophenolic acid with corticosteroid taper ending by 3-6 months. Liver biopsies were performed at each center as annual per protocol and for cause. We defined severe recurrent HCV as any of the following occurring within 2 years of LT 1) METAVIR fibrosis stage ≥2, 2) initiation of HCV treatment post-LT, or 3) repeat LT for graft failure from recurrent HCV. Mild recurrent HCV was defined as METAVIR fibrosis stage < 2 with at least 2 years histologic follow-up and without HCV treatment. To avoid bias from technical complications, recipients who had graft failure within 90 days of LT were excluded, as were subjects with HIV/HCV co-infection. To maximize statistical power and mitigate temporal trends in immunosuppression and HCV treatment, we over matched cases of severe HCV recurrence to controls with mild HCV recurrence based on 1) age at LT +/- 4 years, 2) gender, 3) race (Caucasian, African-American, other) and 4) transplant era (1998-99, 2000-05, 2006-08). Recipient DNA was extracted from pre-LT peripheral blood mononuclear cells or available non-graft tissue samples. Donor DNA was extracted from pre-LT liver graft biopsy specimens, liver graft gallbladder tissue, other donor tissue, or peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Genotyping of IL28B (rs12979860, rs8099917) and DDX58 (rs10813831) SNPs was performed blinded. The test for Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) was carried out using the Caucasian donor samples with no deviation from HWE observed for any of the SNPs (rs12979860: p=0.651; rs8099917: p=0.769; rs10813831: p=0.649). The SNP genotype data were analyzed by conditional logistic regression for matched pairs. All analyses were performed using SAS software®, version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Donor risk index (DRI) was calculated according to Feng et al.[23]. The study was approved by the institutional review boards at each of the participating transplant centers.

Results

Of the 255 recipients with both recipient and donor DNA available, we were able to match 123 severe recurrent HCV cases to 102 mild recurrent HCV controls. Demographics of this group (Group A) are in Table 1. Of the 523 recipients with recipient DNA available, we were able to match 235 severe recurrent HCV cases to 205 mild recurrent HCV controls. Demographics of this group (Group B) are in Table 2. These two matched case-control groups were used for our primary (Group A) and secondary (Group B) analyses.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Matched Group A (total n=225)

| Recipient Characteristics | Mild (n=102) | Severe (n=123) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male (n,%) | 89 | 87.3 | 105 | 85.4 |

| Black Race (n,%) | 4 | 3.9 | 15 | 12.2 |

| Age at LT (median, IQR) | 51 | 48-54 | 52 | 48-55 |

| Era of LT (n,%) | ||||

| 1998-1999 | 9 | 8.8 | 10 | 8.1 |

| 2000-2005 | 57 | 55.9 | 70 | 56.9 |

| 2006-2008 | 36 | 35.3 | 43 | 35.0 |

| Days follow up after LT (median, IQR) | 1872 | 1446-2844 | 1925 | 1124-2644 |

| HCV Genotype 1 | 54/73 | 74.0 | 73/86 | 84.9 |

| Recipient SNP genotype (n,%) | ||||

| R: rs12979860 | ||||

| CC | 35 | 34.3 | 29 | 23.6 |

| CT | 54 | 52.9 | 69 | 56.1 |

| TT | 13 | 12.7 | 25 | 20.3 |

| R: rs8099917 | ||||

| GG | 4 | 3.9 | 9 | 7.3 |

| GT | 39 | 38.2 | 64 | 52.0 |

| TT | 59 | 57.8 | 50 | 40.7 |

| R: rs10813831 | ||||

| AA | 5 | 4.9 | 2 | 1.6 |

| GA | 18 | 17.6 | 33 | 26.8 |

| GG | 76 | 74.5 | 80 | 65.0 |

| Assay Failed | 3 | 2.9 | 8 | 6.5 |

|

| ||||

| Donor Characteristics | ||||

|

| ||||

| Donor Male | 62 | 60.8 | 77 | 62.6 |

| Donor Black Race | 23 | 22.5 | 5 | 4.1 |

| Donor age (median, IQR) | 37 | 23-55 | 40 | 25-51 |

| DRI (median, IQR) | 1.24 | 1.05-1.64 | 1.22 | 1.05-1.51 |

| Donor SNP genotype (n,%) | ||||

| D: rs12979860 | ||||

| CC | 21 | 20.6 | 66 | 53.7 |

| CT | 62 | 60.8 | 42 | 34.1 |

| TT | 18 | 17.6 | 13 | 10.6 |

| Assay Failed | 1 | 1.0 | 2 | 1.6 |

| D: rs8099917 | ||||

| GG | 7 | 6.9 | 7 | 5.7 |

| GT | 38 | 37.3 | 32 | 26.0 |

| TT | 57 | 55.9 | 84 | 68.3 |

| D: rs10813831 | ||||

| AA | 2 | 2.0 | 4 | 3.3 |

| GA | 13 | 12.7 | 29 | 23.6 |

| GG | 87 | 85.3 | 86 | 69.9 |

| Assay Failed | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 3.2 |

LT, Liver Transplantation; IQR, interquartile range; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; R, recipient, D, donor; DRI, donor risk index.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Matched Group B (total n=440).

| Recipient Characteristics | Mild (n=205) | Severe (n=235) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male (n,%) | 174 | 84.9 | 198 | 84.3 |

| Black Race (n,%) | 6 | 2.9 | 11 | 4.7 |

| Age at LT (median, IQR) | 51 | 47-55 | 51 | 47-55 |

| Era of LT (n,%) | ||||

| 1998-1999 | 39 | 19.0 | 41 | 17.4 |

| 2000-2005 | 114 | 55.6 | 125 | 53.4 |

| 2006-2008 | 52 | 25.4 | 69 | 29.5 |

| Days follow up after LT (median, IQR) | 2231 | 1498-3231 | 2106 | 1177-2926 |

| HCV Genotype 1 | 99/137 | 72.3 | 135/162 | 83.3 |

| Recipient SNP genotype (n,%) | ||||

| R: rs12979860 | ||||

| CC | 64 | 31.2 | 52 | 22.1 |

| CT | 116 | 56.6 | 145 | 61.7 |

| TT | 25 | 12.2 | 38 | 16.2 |

| R: rs8099917 | ||||

| GG | 7 | 3.4 | 17 | 7.2 |

| GT | 86 | 42.0 | 116 | 49.4 |

| TT | 112 | 54.6 | 101 | 43.0 |

| Assay Failed | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.4 |

| R: rs10813831 | ||||

| AA | 9 | 4.4 | 7 | 3.0 |

| GA | 36 | 17.6 | 53 | 22.6 |

| GG | 154 | 75.1 | 160 | 68.1 |

| Assay Failed | 6 | 2.9 | 15 | 6.4 |

LT, Liver Transplantation; IQR, interquartile range; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; R, recipient, D, donor.

Donor and Recipient IL28B SNPs and Risk of Severe HCV Recurrence after LT

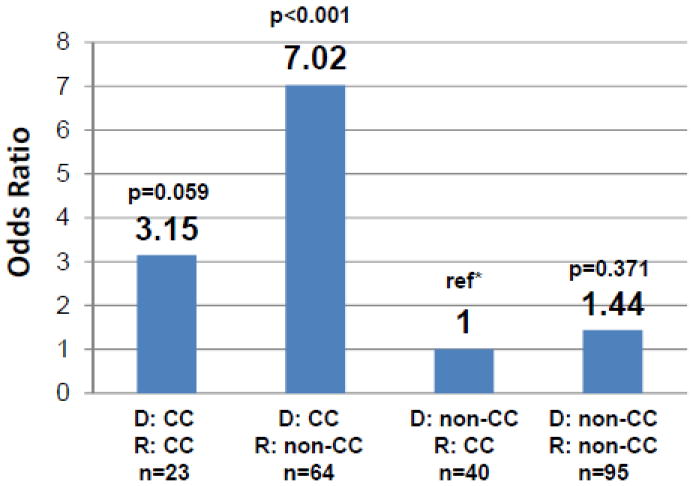

Our primary analysis compared donor vs. recipient IL28B rs12979860 SNP genotypes (as either CC or non-CC) in Group A. Using the lowest risk combination (donor: non-CC and recipient: CC) as the reference, CC-donors conferred greatly increased risk of severe recurrent HCV in non-CC recipients (OR 7.02, 95%CI 2.66-18.52, p<0.001) and a trend towards increased risk in CC recipients (OR 3.15, 95% CI 0.96-10.34, p=0.059) (see Figure 1). Adjusting for donor age or the donor risk index (DRI) resulted in only minimal differences (see Table 3). Previous studies have showed that HCV infected recipients of African American donor livers have improved post-transplant outcomes compared to non-African American donor livers [24, 25]. When evaluating the effect of donor race on the association of donor genotype and severity of HCV after LT, the increased risk conferred by the CC donor genotype remained statistically significant (p<0.001) (see Table 4) yet the effect of non-African American donor race was also significant (p<0.001). Addition of donor age to the model with IL28B rs12979860 genotype and donor race resulted in no detectable change in the risks associated with donor genotype and race, and no improvement in model fit (p=0.42) (see Table 4).

Figure 1.

Risk of severe recurrent HCV after liver transplant in 225 recipients by donor and recipient IL28B rs12979860 genotype presented as non-CC (TT or CT) compared to CC genotype in donors (denoted as D) and recipient (denoted as R). The [C] allele thought to be favorable in the non-transplant setting is associated with increased risk of severe recurrent HCV when present in the donor liver graft. *Reference (ref) is the lowest risk combination of donor non-CC and recipient CC genotype. Number in each group noted as n.

Table 3.

Comparison of conditional logistic regression models with and without donor age and donor risk index

| Model | SNP alone | with Donor age | with DRI | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95%CI | p value | OR | 95%CI | p value | OR | 95%CI | p value | |

| IL28B rs12979860 | |||||||||

| Donor:CC/Recipient:CC | 3.15 | 0.96-10.34 | 0.059 | 3.21 | 0.97-10.61 | 0.056 | 3.02 | 0.92-9.93 | 0.068 |

| Donor:CC/Recipient:non-CC | 7.02 | 2.66-18.52 | <0.001 | 7.02 | 2.66-18.51 | <0.001 | 6.86 | 2.60-18.06 | <0.001 |

| IL28B rs8099917 | |||||||||

| Donor:TT/Recipient:TT | 2.18 | 0.90-5.33 | 0.086 | 2.10 | 0.85-5.17 | 0.106 | 2.41 | 0.96-6.04 | 0.061 |

| Donor:TT/Recipient:non-TT | 5.78 | 2.02-16.53 | 0.001 | 5.78 | 2.02-16.51 | 0.001 | 6.03 | 2.08-17.49 | 0.001 |

| DDX58 rs10813831 | |||||||||

| Donor: non-GG/Recipient non-GG | 4.76 | 0.99-22.90 | 0.052 | 4.77 | 0.99-23.02 | 0.052 | 4.60 | 0.96-21.95 | 0.056 |

| Donor: non-GG/Recipient GG | 2.60 | 1.10-6.13 | 0.029 | 2.63 | 1.11-6.23 | 0.028 | 2.69 | 1.13-6.39 | 0.026 |

Table 4.

Evaluation of the effect of donor race and donor age on the association of donor genotype and severity of HCV after liver transplantation

| Model | SNP alone | With Donor race | With Donor race and donor age | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95%CI | p value | OR | 95%CI | p value | OR | 95%CI | p value | |

| IL28B rs12979860 | |||||||||

| Donor CC vs Donor non-CC | 4.29 | 2.21-8.32 | <0.001 | 4.50 | 2.21-9.24 | <0.001 | 4.63 | 2.24-9.59 | <0.001 |

| IL28B rs8099917 | |||||||||

| Donor TT vs Donor non-TT | 1.80 | 0.98-3.32 | 0.059 | 3.39 | 1.58-7.28 | 0.002 | 3.40 | 1.58-7.32 | 0.002 |

| DDX58 rs10813831 | |||||||||

| Donor non-GG vs Donor GG | 2.26 | 1.11-4.58 | 0.024 | 1.87 | 0.87-4.01 | 0.107 | 1.86 | 0.86-3.99 | 0.113 |

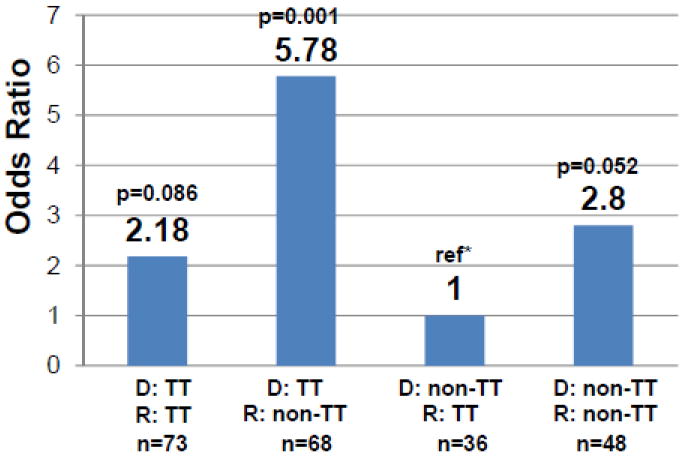

Next, we compared the IL28B rs8099917 genotype (as either TT or non-TT) in donors and recipients. Using the lowest risk combination (donor: non-TT and recipient: TT) as the reference, we found that TT-donors conferred significantly increased risk in non-TT recipients (OR 5.78, 95%CI 2.02-16.53, p=0.001), with a trend towards increased risk in TT recipients (OR 2.18, 95% CI 0.90-5.33, p=0.086) (see Figure 2). Adjusting for donor age or the donor risk index (DRI) resulted in only minimal differences (see Table 3). When evaluating the effect of donor race on the association of donor genotype and severity of HCV after LT, the increased risk conferred by the TT donor genotype was statistically significant (p=0.002) (see Table 4) yet the effect of non-African American donor race was also significant (p<0.001). Addition of donor age to the model with IL28B rs8099917 genotype and donor race resulted in no detectable change in the risks associated with donor genotype and race, and no improvement in model fit (p=0.63). (see Table 4) As two prior studies in the non-transplant setting have reported that HCV genotype may influence HCV related fibrosis[26, 27] and its association with IL28B SNPs, we assessed the potential influence of HCV genotype on our findings (see Table 5) and found that our results were robust to HCV genotype.

Figure 2.

Risk of severe recurrent HCV after liver transplant in 225 recipients by donor and recipient IL28B rs8099917 genotype presented as non-TT (GG or GT) compared to TT genotype in donors (denoted as D) and recipient (denoted as R). The [T] allele thought to be favorable in the non-transplant setting is associated with increased risk of severe recurrent HCV when present in the donor liver graft. *Reference (ref) is the lowest risk combination of donor non-TT and recipient TT genotype. Number in each group noted as n.

Table 5.

Comparison of conditional logistic regression models with and without HCV genotype (1 vs non-1)

| Model | SNP alone | with HCV Genotype | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95%CI | p value | OR | 95%CI | p value | |

| IL28B rs12979860 | ||||||

| Donor:CC/Recipient:CC | 3.15 | 0.96-10.34 | 0.059 | 5.81 | 0.72-46.78 | 0.098 |

| Donor:CC/Recipient:non-CC | 7.02 | 2.66-18.52 | <0.001 | 25.91 | 2.69-249.91 | 0.005 |

| IL28B rs8099917 | ||||||

| Donor:TT/Recipient:TT | 2.18 | 0.90-5.33 | 0.086 | 2.59 | 0.57-11.75 | 0.218 |

| Donor:TT/Recipient:non-TT | 5.78 | 2.02-16.53 | 0.001 | 7.86 | 1.44-42.94 | 0.017 |

| DDX58 rs10813831 | ||||||

| Donor: non-GG/Recipient non-GG | 4.76 | 0.99-22.90 | 0.052 | 4.83 | 0.42-55.56 | 0.207 |

| Donor: non-GG/Recipient GG | 2.60 | 1.10-6.13 | 0.029 | 4.49 | 1.12-17.99 | 0.034 |

Together, these results show that the effect of IL28B genotype varies depending on whether the genotype is of donor or recipient origin. Although a recipient rs12979860 CC genotype may confer higher rates of spontaneous and treatment-related HCV clearance in the non-transplant setting, a donor liver with the CC genotype is associated with increased risk of severe recurrent HCV after LT. Similarly, for rs8099917, for which in the non-transplant setting the TT genotype is favorable, in our study the rs8099917 TT donor conferred increased risk of severe HCV after LT in all recipients (recipient: TT or recipient: non-TT). Importantly, the increased risk associated with these donor liver SNP genotypes persisted after controlling for donor age, donor race and donor risk index.

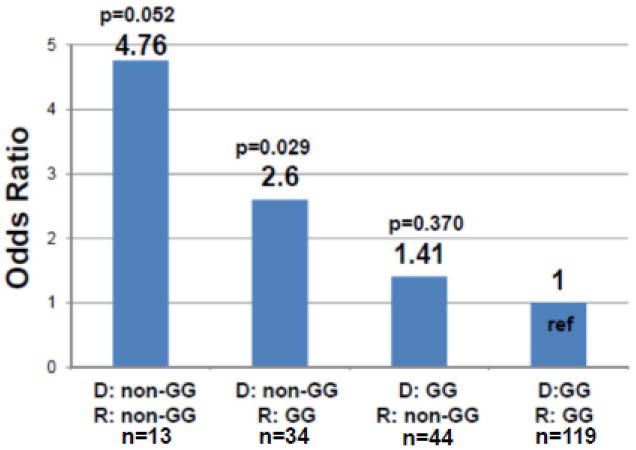

Donor and Recipient DDX58 Genotype and Risk of Severe HCV Recurrence after LT

We next investigated a functional SNP (rs10813831) in DDX58 which encodes a crucial caspase activation and recruitment domain of the RIG-I (retinoic acid inducible gene-I) protein. RIG-I is component of the innate immune system, acting as a cytoplasmic surveillance molecule detecting dsRNA of viruses, including HCV[28, 29]. IL28B SNPs are associated with the differential expression of intrahepatic interferon-stimulated genes[30] including DDX58 and the minor allele [A] of rs10813831 may modulate antiviral innate responses via DDX58 expression[14].

We analyzed DDX58 SNP rs10813831 in a similar manner as for the IL28B SNPs using the same case-control group, Group A. When using the lowest risk combination (donor: GG and recipient: GG) as the reference, non-GG donors conferred an increased risk of severe recurrent HCV in non-GG recipients (OR 4.76, 95% CI 0.99-22.90, p=0.052) and in GG recipients (OR 2.6, 95%CI 1.10-6.13, p=0.029) (see Figure 3). Adjusting for donor age or the donor risk index (DRI) resulted in only minimal differences (see Table 3). When evaluating the effect of donor race on the association of donor genotype and severity of HCV after LT, recipients of non-African American donor livers had a significantly higher risk of severe HCV after LT (p=0.002) and the odds ratio for severe recurrence for the non-GG donors reduced from 2.26 to 1.87. (see Table 4) This may be explained by the association between the DDX58 geneotype and race, since 25 of the 28 African-American donor livers were genotype GG. Addition of donor age to the model with DDX58 rs10813831 genotype and donor race resulted in no detectable change in the risks associated with donor genotype and race, and no improvement in model fit (p=0.81)(see Table 4). We also evaluated whether there was an association between DDX58 rs10813831 SNP and each of the two IL28B SNPs (rs12979860 rs8099917) in the donors and then in the recipients. We did not detect a statistically significant association between rs10813831 and rs12979860 or rs10813831 and rs8099917 in either the donor or recipient.

Figure 3.

Risk of severe recurrent HCV after liver transplant by donor and recipient DDX58 (rs10813831) SNP genotype presented as non-GG (AA or AG) compared to GG in donors (denoted as D) and recipients (denoted as R). *Reference (ref) is the lowest risk combination of donor GG and recipient GG genotype. Number in each group noted as n.

Recipient Alone IL28B and DDX58 SNPs and Risk of Severe HCV Recurrence after LT

As a secondary analysis, we examined matched Groups A (n=225) and B (n=440) using all available donor and recipient demographics, yet only recipient DNA. Similar to previous smaller studies[17-20], our analysis of group A showed increased risk of severe recurrent HCV after LT with recipient rs8099917 non-TT genotype (OR 2.37, 95% CI 1.26-4.48, p=0.008) and a numerical increase, though not statistically significant, in the risk of severe HCV recurrence with recipient rs12979860 non-CC genotype (OR 1.54, 95% CI 0.87-2.72, p=0.137). Adjusting for donor age or the donor risk index (DRI) yielded only minimal differences. Analogous analysis of our larger matched group, Group B, likewise showed increased risk of severe recurrent HCV after LT with recipient rs8099917 non-TT genotype (OR 1.58, 95% CI 1.07-2.33, p=0.021) and recipient rs12979860 non-CC genotype (OR 1.57, 95% CI 1.01-2.45, p=0.047). Nevertheless, recipient only rs10813831 showed no association with severity of HCV after LT in either matched Group A (OR 1.43, 95%CI 0.77-2.64, p=0.258) or Group B (OR 1.19, 95% CI 0.78-1.81, p=0.431).

Discussion

We have carried out the largest case-control study reported to date and find that the outcome of HCV recurrence after LT is determined by genotypic differences in SNPs at IL28B and DDX58. Surprisingly, the phenotypic effect of the IL28B genotypes appear to vary depending on whether the genotype is of donor or recipient origin, and the effects of donor and recipient genotype are contradictory. Although recipient rs12979860 CC genotype confers higher rates of spontaneous and treatment-related HCV clearance in the non-transplant setting, here, we found that receiving a donor liver with the rs12979860 CC genotype is associated with increased risk of severe recurrent HCV after LT. This finding is supportive of two recent smaller studies where donor rs12979860 CC was associated with unfavorable post-LT events (higher risk for recurrent cirrhosis, need for retransplantation or death) and donor rs12979860 T allele with favorable post-LT events (lower risk for advanced fibrosis within 5 years)[21, 22]. Similarly, for rs8099917 (for which in the non-transplant setting the TT genotype is favorable) in our study the TT donor was associated with increased rather than reduced risk of severe HCV after LT.

In addition to the IL28B SNPs, we obtained similar results with a SNP in another gene involved in IFN signaling, DDX58. Carriage of the minor allele [A] of rs10813831 has been associated with increased DDX58 expression, which is an important step in antiviral innate immunity in the non-transplant setting [14]. Rs10813831 AA homozygotes are relatively uncommon in the general population (7.7%)[14], and likewise were uncommon in our study population. Nevertheless, when the donor liver was rs10813831 non-GG (vs. GA or AA), we observed higher (not lower) risk for severe HCV after LT. Taken together with our IL28B SNP findings, these data provide additional support for a differential (worse) phenotypic effect of these genotypes on HCV outcomes when present in a donor liver versus when present in the LT recipient or non-transplant HCV- infected patient.

A recent study by Asahina and colleagues demonstrated that hepatic expression levels of RIG-I were higher in IL28B minor patients (non-CC for rs12970860 and non-TT for rs8099917) and also associated with treatment failure in non-transplant patients. The latter study, however, did not examine genotypic associations between IL28B and DDX58 and the transcriptional expression of these genes. Differences in expression level of RIG-I are regulated by endogenous interferon (IFN) and this may vary within IL28B major and minor patients[31] and in different cell types. For example, hepatocytes may express higher levels of RIG-I than dendritic cells (DCs) [14], and HCV infection and the subsequent production of IFN may further induce RIG-I. These are speculative conclusions that would require further studies including simultaneous analysis of SNPs with mRNA expression. Nonetheless, the fact we found an association between a functional SNP in RIG-I (identified by Hu and colleagues[14] using transfection and reporter assays) and more severe HCV recurrence is consistent with the hypothesis that innate immunity induces collateral injury and fibrosis without leading to viral control following liver transplantation.

Population stratification is an important consideration for any genetic association study, but especially for studies of a multi-ethnic nature. To date, the vast majority of genetic research has addressed the issue of stratification by using a genetically homogenous population (i.e. Caucasian-only). However, there has been a recent push for the use of multi-ethnic samples to generalize findings and in some cases, improve statistical power [32]. As noted by Tang et al. [33], self-identified race is highly correlated with genetic ancestry and self-identified race can be used to capture genetic structure when conducting a genetic association study in the absence of ancestry informative markers (or genome-wide information). Therefore, to adopt a multi-ethnic approach and address stratification concerns, we used two different approaches. First, we included a covariate term indicating self-identified race in our statistical models to “control” for genetic ancestry. Second, we restricted our analysis to non-African American and Caucasian-only to assess whether parameter estimates changed substantially when compared to the full-sample analysis. Results of these approaches were consistent with minimal bias due to stratification effects. As shown in supplemental Table S1, despite the loss in statistical power, the Caucasian-only, Caucasian/Hispanic-only and non-African American analyses yielded parameter estimates in the same direction and general magnitude as the full-sample analysis for all three SNPs.

Two prior studies report that HCV infected LT recipients of African-American liver grafts have improved outcomes (lower graft loss and patient mortality) after LT [24, 25]. Whether this improved outcome after LT for HCV with African-American donors is a result of a higher prevalence of the donor IL28B genotypes (rs12979860 non-CC genotype and rs8099917 non-TT) demonstrated in our study to be favorable is unknown. In our study, the IL28B genotype remained significantly associated with severity of HCV after LT when allowing for donor race in the analysis. Although we are unable to determine whether IL28B genotype is the sole or dominant explanatory factor of the favorable association of African-American liver grafts on the severity of HCV after LT, we demonstrate that IL28B genotype is an important predictor of severity of HCV after LT even after controlling for donor race.

These data suggest that a donor liver “programmed” for a more robust, activated innate immune response might be a risk factor for severe recurrence, perhaps because the requisite immunosuppression following liver transplantation leads to an ultimately ineffective immune response within the donor hepatocytes. This process results HCV-related inflammation, fibrosis and graft failure. This concept is in keeping with data on donor TNF-a gene polymorphisms, first suggested over a decade ago[34]. The fact we found that SNPs associated with enhanced production of both RIG-I, the cytosolic receptor involved in recognition of hepatitis C viral RNA and induction of downstream IFN pathways, as well as IL28B (a Type III IFN), support the concept that paradoxically, activated innate immunity may have a detrimental effect in the transplant setting where viral clearance does not take place. On the other hand, sustained virologic response to combination antiviral therapy following LT[22] is facilitated by the presence of the favorable IL28B genotype within the donor, approaching 90% when combined with favorable genotype within the recipient. Clearly, further work is warranted to understand the mechanisms of how Type I and III IFNs might be co-regulated.

Recent data demonstrated that up regulation of interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs) within Kupffer cells was a strong positive and independent predictor of subsequent response to antiviral therapy, whereas hepatocyte ISG expression was associated with non-response[35], underscoring the importance of examining different patterns of cellular activation in determining outcome of HCV infection. Moreover, a recent study demonstrated that the good response IL28B variant in non-transplant HCV-positive patients with mild-to-moderate hepatic necroinflammation and fibrosis was associated with lower hepatic ISG expression [30]. In this regard, it is possible that attenuated ISG responses within the donor allograft facilitates viral replication and spread. Unfortunately, we did not have stored hepatic tissue following liver transplantation to test these hypotheses. The lack of association between IL28B SNPs and hepatic expression of Type III IFNs reported in the literature indicate that non-hepatocytes also likely produce Type III IFNs. We suspect that the main cellular sources of IFNs are plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) and other innate immune cells[36] that are recipient-derived, infiltrate the allograft, and respond to HCV infection. We have recently found that pDCs transfected with HCV RNA produce higher levels of Type III IFNs in CC subjects as compared to those expressing the T allele either singly or as a homozygote. The fact we found that recipient genotype associated with favorable outcome in the non-transplant setting was relatively protective following LT indicates a functional role of polymorphisms in the IL28B gene locus within cells such as DCs that would infiltrate the allograft.

To confirm and extend our observation that the IL28B rs12979860 CC and rs8099917 TT genotypes in the recipient are associated with favorable effects on the natural history of HCV after LT, we first restricted our primary study group (Group A) to recipient-only information and then repeated the analysis in an identically matched, larger secondary study group (Group B) for which donor DNA was not available. Our over matched case-control study design and large sample size provide perhaps the most precise point estimates of the recipient effect of IL28B genotype on the risk of severe recurrent HCV after LT. Consistent with prior studies [17-20], our recipient-only analyses showed that the rs12979860 non-CC and rs8099917 non-TT IL28B genotypes in a recipient are associated with increased risk of severe HCV after LT with ~60% increase in the risk of severe HCV recurrence in recipients with the rs12979860 non-CC or rs8099917 non-TT genotypes. As the donor genotypes may not be available in many cases, such recipient data may be of significant clinical relevance.

Similar to prior cohort studies, we observed higher prevalence of non-favorable IL28B SNP genotypes among the recipients as compared to donors (data not shown). Additionally, we compared the allele frequency for each of our 3 SNPs in our 225 donor population to a cohort of 85 healthy volunteers recruited at two of the transplant centers in the study (UCD and OHSU). In an allele based analysis using Chi-squared test, there was no detectable difference between the donors in our primary analysis and the health volunteers for the rs12979860 (p=0.131), rs8099917 (p=0.295) or rs10813831 (p=0.968). Similarly, when testing in the subset of 180 Caucasian donors and 44 Caucasian healthy volunteers, there was no detectable difference for each of the SNPS, rs12979860 (p=0.793), rs8099917 (p=0.619) or rs10813831 (p=0.976). Therefore, we conclude that our donors did not differ significantly from the general population.

Importantly, our study design minimizes bias in estimates of SNP associations with severity of HCV, while controlling for measured and unmeasured confounders by matching by race, gender, age and era of transplantation, which may mitigate the influence of important recipient confounders and of practice patterns over the duration of the study such as changes in immunosuppressive regimens, HCV treatment protocols and decision to pursue repeat liver transplantation. Our outcome (and definition for mild recurrence) was ascertained with a minimum of two years after liver transplant. While we have longer-term follow-up on both groups (see table 1 and 2 for median follow-up), our study findings are limited to an a prior outcome at 2 years after transplant.

In conclusion, in the largest study that we are aware of evaluating the recipient and donor IL28B SNP and the only study evaluating the DDX58 genotype, we have found that the effect of genotypes on recurrent HCV after LT appear to vary depending on whether the genotype is of donor or recipient origin. Genotypes previously thought to have a favorable influence on HCV outcomes in the non-transplant setting, such as rs12979860 CC and rs8099917 TT, have an unfavorable influence when transferred to a recipient in a donor liver. Our findings have implications for understanding the mechanisms of HCV-related allograft injury and identifying patients with a more aggressive natural history of HCV and therefore a subset in whom antiviral therapy should be strongly considered.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was funded in part by grants from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (DK076565) and from Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (DK076565) to S.W.B and K24 AI083742 and VA Merit Review Grant to H.R.R.

Abbreviations

- IL

interleukin

- SNP

single nucleotide polymorphism

- HCV

hepatitis C virus

- LT

liver transplantation

- OR

odds ratio

- CI

confidence interval

- IFN

interferon

- pDC

plasmacytoid dendritic cells

- TNF

tumor necrosis factor

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Berenguer M, Ferrell L, Watson J, Prieto M, Kim M, Rayon M, et al. HCV-related fibrosis progression following liver transplantation: increase in recent years. J Hepatol. 2000;32:673–684. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(00)80231-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gane EJ, Portmann BC, Naoumov NV, Smith HM, Underhill JA, Donaldson PT, et al. Long-term outcome of hepatitis C infection after liver transplantation. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:815–820. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199603283341302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sanchez-Fueyo A, Restrepo JC, Quinto L, Bruguera M, Grande L, Sanchez-Tapias JM, et al. Impact of the recurrence of hepatitis C virus infection after liver transplantation on the long-term viability of the graft. Transplantation. 2002;73:56–63. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200201150-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garg V, van Heeswijk R, Lee JE, Alves K, Nadkarni P, Luo X. Effect of telaprevir on the pharmacokinetics of cyclosporine and tacrolimus. Hepatology. 2011;54:20–27. doi: 10.1002/hep.24443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Charlton M. Telaprevir, boceprevir, cytochrome P450 and immunosuppressive agents--a potentially lethal cocktail. Hepatology. 2011;54:3–5. doi: 10.1002/hep.24470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Asselah T. A sprint to increase response to HCV treatment: Expectancies but caution. J Hepatol. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Asselah T. Realize the advance in HCV treatment, but remain cautious. J Hepatol. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rauch A, Kutalik Z, Descombes P, Cai T, Di Iulio J, Mueller T, et al. Genetic variation in IL28B is associated with chronic hepatitis C and treatment failure: a genome-wide association study. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:1338–1345. 1345 e1331–1337. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.12.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thomas DL, Thio CL, Martin MP, Qi Y, Ge D, O’Huigin C, et al. Genetic variation in IL28B and spontaneous clearance of hepatitis C virus. Nature. 2009;461:798–801. doi: 10.1038/nature08463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ge D, Fellay J, Thompson AJ, Simon JS, Shianna KV, Urban TJ, et al. Genetic variation in IL28B predicts hepatitis C treatment-induced viral clearance. Nature. 2009;461:399–401. doi: 10.1038/nature08309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suppiah V, Moldovan M, Ahlenstiel G, Berg T, Weltman M, Abate ML, et al. IL28B is associated with response to chronic hepatitis C interferon-alpha and ribavirin therapy. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1100–1104. doi: 10.1038/ng.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tanaka Y, Nishida N, Sugiyama M, Kurosaki M, Matsuura K, Sakamoto N, et al. Genome-wide association of IL28B with response to pegylated interferon-alpha and ribavirin therapy for chronic hepatitis C. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1105–1109. doi: 10.1038/ng.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosen HR. Clinical practice. Chronic hepatitis C infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2429–2438. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1006613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hu J, Nistal-Villan E, Voho A, Ganee A, Kumar M, Ding Y, et al. A common polymorphism in the caspase recruitment domain of RIG-I modifies the innate immune response of human dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2010;185:424–432. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pothlichet J, Burtey A, Kubarenko AV, Caignard G, Solhonne B, Tangy F, et al. Study of human RIG-I polymorphisms identifies two variants with an opposite impact on the antiviral immune response. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7582. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Horner SM, Gale M., Jr Intracellular innate immune cascades and interferon defenses that control hepatitis C virus. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2009;29:489–498. doi: 10.1089/jir.2009.0063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Charlton MR, Thompson A, Veldt BJ, Watt K, Tillmann H, Poterucha JJ, et al. Interleukin-28B polymorphisms are associated with histological recurrence and treatment response following liver transplantation in patients with hepatitis C virus infection. Hepatology. 2011;53:317–324. doi: 10.1002/hep.24074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coto-Llerena M, Perez-Del-Pulgar S, Crespo G, Carrion JA, Martinez SM, Sanchez-Tapias JM, et al. Donor and recipient IL28B polymorphisms in HCV-infected patients undergoing antiviral therapy before and after liver transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2011;11:1051–1057. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03491.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fukuhara T, Taketomi A, Motomura T, Okano S, Ninomiya A, Abe T, et al. Variants in IL28B in liver recipients and donors correlate with response to peg-interferon and ribavirin therapy for recurrent hepatitis C. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:1577–1585. 1585 e1571–1573. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.07.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lange CM, Moradpour D, Doehring A, Lehr HA, Mullhaupt B, Bibert S, et al. Impact of donor and recipient IL28B rs12979860 genotypes on hepatitis C virus liver graft reinfection. J Hepatol. 2011;55:322–327. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cisneros E, Banos I, Citores MJ, Duca A, Salas C, Noblejas A, et al. Increased risk of severe hepatitis C virus recurrence after liver transplantation in patients with a T allele of IL28B rs12979860. Transplantation. 2012;94:275–280. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31825668f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Duarte-Rojo A, Veldt BJ, Goldstein DD, Tillman HL, Watt KD, Heimbach JK, et al. The course of posttransplant hepatitis C infection: comparative impact of donor and recipient source of the favorable IL28B genotype and other variables. Transplantation. 2012;94:197–203. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3182547551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Feng S, Goodrich NP, Bragg-Gresham JL, Dykstra DM, Punch JD, DebRoy MA, et al. Characteristics associated with liver graft failure: the concept of a donor risk index. Am J Transplant. 2006;6:783–790. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01242.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Layden JE, Cotler SJ, Grim SA, Fischer MJ, Lucey MR, Clark NM. Impact of donor and recipient race on survival after hepatitis C-related liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2012;93:444–449. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3182406a94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saxena V, Lai JC, O’Leary JG, Verna EC, Brown RS, Jr, Stravitz RT, et al. Recipient-donor race mismatch for African American liver transplant patients with chronic hepatitis C. Liver Transpl. 2012;18:524–531. doi: 10.1002/lt.22461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bochud PY, Bibert S, Kutalik Z, Patin E, Guergnon J, Nalpas B, et al. IL28B alleles associated with poor hepatitis C virus (HCV) clearance protect against inflammation and fibrosis in patients infected with non-1 HCV genotypes. Hepatology. 2012;55:384–394. doi: 10.1002/hep.24678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marabita F, Aghemo A, De Nicola S, Rumi MG, Cheroni C, Scavelli R, et al. Genetic variation in the interleukin-28B gene is not associated with fibrosis progression in patients with chronic hepatitis C and known date of infection. Hepatology. 2011;54:1127–1134. doi: 10.1002/hep.24503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cheng G, Zhong J, Chisari FV. Inhibition of dsRNA-induced signaling in hepatitis C virus-infected cells by NS3 protease-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:8499–8504. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602957103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saito T, Hirai R, Loo YM, Owen D, Johnson CL, Sinha SC, et al. Regulation of innate antiviral defenses through a shared repressor domain in RIG-I and LGP2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:582–587. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606699104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Urban TJ, Thompson AJ, Bradrick SS, Fellay J, Schuppan D, Cronin KD, et al. IL28B genotype is associated with differential expression of intrahepatic interferon-stimulated genes in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2010;52:1888–1896. doi: 10.1002/hep.23912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Asahina Y, Tsuchiya K, Muraoka M, Tanaka K, Suzuki Y, Tamaki N, et al. Association of gene expression involving innate immunity and genetic variation in interleukin 28B with antiviral response. Hepatology. 2012;55:20–29. doi: 10.1002/hep.24623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pulit SL, Voight BF, de Bakker PI. Multiethnic genetic association studies improve power for locus discovery. PLoS One. 2010;5:e12600. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tang H, Quertermous T, Rodriguez B, Kardia SL, Zhu X, Brown A, et al. Genetic structure, self-identified race/ethnicity, and confounding in case-control association studies. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;76:268–275. doi: 10.1086/427888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rosen HR, Lentz JJ, Rose SL, Rabkin J, Corless CL, Taylor K, et al. Donor polymorphism of tumor necrosis factor gene: relationship with variable severity of hepatitis C recurrence after liver transplantation. Transplantation. 1999;68:1898–1902. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199912270-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen L, Borozan I, Sun J, Guindi M, Fischer S, Feld J, et al. Cell-type specific gene expression signature in liver underlies response to interferon therapy in chronic hepatitis C infection. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:1123–1133. e1121–1123. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.10.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Balagopal A, Thomas DL, Thio CL. IL28B and the control of hepatitis C virus infection. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:1865–1876. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.