Abstract

DAP12 and its associating molecules MDL-1, TREM-1, and TREM-2 are the recently identified immune regulatory molecules, expressed primarily on myeloid cells including monocytes/macrophages, dendritic cells, NK cells, and neutrophils. However, little is known about the regulation of their expression during host antimicrobial responses. We have investigated the effect of pulmonary mycobacterial infection and type 1 cytokines on the expression of these molecules both in vivo and in vitro. While DAP12 was constitutively expressed at high levels in the lungs, the MDL-1, TREM-1, and TREM-2 molecules were inducible during mycobacterial infection. Their kinetic expression was correlated with that of the type 1 cytokines tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and gamma interferon (IFN-γ). In primary lung macrophage cultures, high constitutive levels of DAP12 and TREM-2 were not modulated by mycobacterial or type 1 cytokine exposure. In contrast, expression of both MDL-1 and TREM-1 was markedly induced by mycobacterial infection and such induction was inhibited by concurrent exposure to IFN-γ. On mycobacterial infection of TNF-α−/− and IFN-γ−/− mice in vivo or their lung macrophages in vitro, TNF-α was found to be critical for mycobacterially induced MDL-1, but not TREM-1, expression whereas IFN-γ negatively regulated mycobacterially induced MDL-1 and TREM-1 expression. Our findings thus suggest that DAP12 and its associating molecules are differentially regulated by mycobacterial infection and type 1 cytokines and that MDL-1- and TREM-1-triggered DAP12 signaling may play an important role in antimicrobial type 1 immunity.

DAP12 (KARAP) is a recently discovered immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif-bearing transmembrane adapter molecule (3, 19, 22) and serves to transmit signals into the cell on engagement with a group of DAP12-associating cell surface molecules including killer cell-activating receptors, myeloid DAP12-associating lectin 1 (MDL-1), triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells types 1, 2, and 3 (TREM-1, TREM-2, and TREM-3) and signal regulatory protein β1 (SIRP β1) (4, 7, 11, 17, 19, 22). DAP12 and its associating molecules are expressed primarily on NK cells and myeloid cell types including macrophages, dendritic cells, and neutrophils (4, 7, 9, 10, 17, 25). The role of these cell surface molecules in inflammatory and immune responses remains to be understood. However, recent evidence obtained by us and others suggests that the DAP12-mediated signaling pathway may play a regulatory role in host immune responses. For instance, blockade of TREM-1-triggered DAP12 signaling by using a TREM-1 antagonist conferred protection from lethal endotoxic shock in mice, implicating the DAP12 signaling pathway in acute inflammatory responses (8). Furthermore, DAP12 deficient mice had inadequate T-cell priming by antigen-presenting cells in models of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis and contact dermatitis and suffered weakened host defenses against murine cytomegalovirus infection (5, 24, 26). We have recently demonstrated the role of DAP12 in the process of macrophage differentiation (1, 2) and shown that transgenic expression of DAP12 augmented zymosan A-induced granuloma formation whereas blockade of TREM-1-mediated DAP12 signaling markedly inhibited such granuloma formation (21). These results suggest that the DAP12 signaling pathway also plays a regulatory role in chronic immune responses.

Further understanding of the role of DAP12 and its associating molecules in inflammatory and immune responses requires our knowledge of the regulation of expression of these cell surface molecules in a variety of immunologic processes. In this regard, little is known about whether these molecules are differentially expressed and whether infectious agents and immune modulatory cytokines regulate their expression both in vitro and in vivo. In the present study, by using in vitro and in vivo models of mycobacterial infection, we have investigated the effect of mycobacteria and type 1 cytokines on expression of DAP12 and its associating molecules.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

C57BL/6 mice aged 8 to 14 weeks were purchased from Harlan Laboratories (Indianapolis, Ind.). These mice were housed at the McMaster Central Animal facility under level B specific-pathogen-free (SPF) conditions. Both gamma interferon-negative (IFN-γ−/−) and tumor necrosis factor alpha-negative (TNF-α−/−) mice (C57BL/6 background) were bred in our central animal facility under SPF conditions and used at 8 to 14 weeks of age. All experiments were performed in accordance with the guidelines of the Animal Research Ethics board of McMaster University.

In vivo model of pulmonary mycobacterial infection.

Live Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) was originally obtained from Connaught Laoboratories (North York, Canada). It was grown in Middlebrook 7H9 broth (Difco, Detroit, Mich.) supplemented with Middlebrook OADC enrichment (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, Md.), 0.002% glycerol, and 0.05% Tween 80. Pulmonary mycobacterial infection was established by intratracheal instillation of live BCG at a dose of 0.5 × 106 CFU in a total volume of 40 μl/mouse as previously described (28, 29, 31, 33).

BAL.

Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) was extracted by using a previously described standard procedure (28, 29, 31, 33). Briefly, the lungs were removed from the thoracic cavity with the heart and a portion of the trachea intact. To collect BAL fluid, a polyethylene tube (Becton Dickinson, Sparks, Md.) was used to cannulate the trachea. For measurements of cytokine levels, the lungs were lavaged twice with phosphate-buffered saline (0.25 and 0.2 ml, consecutively). For isolation of macrophages, lungs were lavaged five to seven times with phosphate-buffered saline (0.25 ml the first time and 0.3 ml each subsequent time). Approximately 0.6 × 106 to 1 × 106 cells per mouse were consistently obtained, and more than 98% of these cells were macrophages.

Lung macrophage culture conditions and in vitro stimulation.

Isolated macrophages were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 5 × 10−5 M 2-mercaptoethanol, 100 U of penicillin per ml, and 100 μg of streptomycin per ml. For in vitro stimulation, macrophages were cultured in 12-well plates at a density of 0.8 × 106 to 1 × 106 cells per cell with or without various stimuli, including 2 CFU of live BCG per cell, 5 ng of TNF-α per ml, 5 ng of IFN-γ per ml, or 1μg of lipopolysaccharide per ml (LPS) in a total volume of 2 ml for 40 h. Recombinant cytokines were purchased from Research Diagnostics, Inc., Flanders, N.J.

Measurement of cytokine levels in BAL fluid.

Cytokine levels in BAL fluid were measured by specific enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). All ELISA kits were purchased from R&D Systems (Mineapolis, Minn.) The sensitivity of detection was ≤5 pg/ml.

Antibodies.

Rabbit anti-mouse DAP12 polyclonal antibody was generated by immunizing a rabbit (Japanese White) with glutathione S-transferase-conjugated mouse DAP12 cytoplasmic domain fusion protein as described previously (1).

Immunoprecipitation, electrophoresis, and blotting for detection of DAP12 protein.

Immunoprecipitation, electrophoresis, and blotting were carried out as previously described (1). Briefly, lung tissues were homogenized and then lysed in lysis buffer (0.5 % Triton X-100, 50 mM Tris [pH 8.0], 140 mM NaCl, 10 mM EDTA) containing the protease inhibitor cocktail Complete Mini (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). Lysates were then cleared by centrifugation and immunoprecipitated for 1 to 2 h at 4°C with anti-DAP12 antibodies bound to rProtein A-Sepharose Fast Flow (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech AB, Uppsala Sweden). The resulting immunocomplexes were washed and run on Ready Gel Tris-HCl 10 to 20% gradient gels (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, Calif.) or sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-14% polyacrylamide gels under reducing conditions. The proteins were then blotted onto Immobilon-P (Millipore, Bedford, Mass.), blocked in 5% skim milk, and probed with rabbit anti-DAP12 antibody followed by using donkey anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech AB). The enhanced chemiluminescence system (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech AB) was used for detection.

Detection of mRNA of DAP12 and associating molecules by RT-PCR and real-time quantitative PCR.

Total RNA was prepared by using Trizol (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, Calif.) as specified by the manufacturer. cDNA was prepared from 1.5 μg of total RNA by using the SuperScript first-strand synthesis system for reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) (Invitrogen life technologies). The following primers were used for RT-PCR amplification: DAP12 forward (5′- ACC AGC CCC TGG ACT GTG GTG TCC AG-3′), DAP12 reverse (5′- GTA CCC TGT GGA TCT GTA TTC CAA C-3′), MDL-1 forward (5′- CGG AAT TCC AGA AAG AGA TCA GAT CCC TGA ATC C -3′), MDL-1 reverse (5′- GCT CTA GAT TTC CTG GGC TGG TTT CAG TCA CAA C -3′), TREM-1 forward (5′-CGG AAT TCG AGC TTG AAG GAT GAG GAA GGC-3′), TREM-1 reverse (5′-AAT CCA GAG TCT GTC ACT TGA AGG TCA GTC-3′), TREM-2 forward (5′-GGT GCC ATG GGA CCT CTC CAC CAG TTT CTC-3′) TREM-2 reverse (5′- CTT CAG AGT GAT GGT GAC GGT TCC AGC AAG -3′), TNF-α forward, (5′- GGC AGG TCT ACT TTG GAG TCA TTG C -3′) TNF-α reverse, (5′- ACA TTC GAG GCT CCA GTG AAT TCG G -3′), <?zsq(5′- TGG AAT CCT GTG GCA TCC ATG AAA C -3′), and β-actin reverse (5′- TAA AAC GCA GCT CAG TAA CAG TCC G -3′). PCR was performed under the conditions of an initial 1 min at 94°C, followed by 22 cycles for β-actin or 30 cycles for other molecules (5 s at 94°C, 30 s at 60°C, and 90 s at 72°C), with a final 7 min at 72°C. PCR products after electrophoresis were imaged by using Gel Doc 2000 (Bio-Rad Laboratories).

The procedures of real-time quantitative PCR were carried out as previously described (23). Briefly, primers and FAM-labeled probes were designed using Primer Express v1.5 software (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.) as follows: DAP12 forward (5′-TGG TGC CTT CTG TTC CTT CCT-3′), DAP12 reverse (5′-CAG AAC AAT CCC AGC CAG TAC A-3′), DAP12 probe (5′-TGC GAC TGT TCT TCC GTG AGC CC-3′), MDL-1 forward (5′- CCT TGG AAA GAC AGC ATG GAT TA-3′), MDL-1 reverse (5′- ACT TCA GTT TCT CTG GAG TGT TGA CA-3′), MDL-1 probe (5′- TGT GCA ACA CAA GGA TCC ACA CTG GC-3′), TREM-1 forward (5′- GAC GGG AAG GAA CCC TTG AC-3′), TREM-1 reverse (5′- ACT TCC CCA TGT GGA CTT CAC T-3′), and TREM-1 probe (5′- CTG GTG GTC ACA CAG AGG CCC TTT ACA A-3′). Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) primers and VIC-labeled probes were purchased from Applied Biosystems. PCR was performed in an ABI Prism 6700 sequence detection instrument operated by Sequence Detector v1.7 software using TaqMan Universal PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems). Gene expression was quantitated relative to the expression of GAPDH, using the established standard curves.

RESULTS

Expression of DAP12 and its associating molecules in the lungs of wild-type mice during mycobacterial infection.

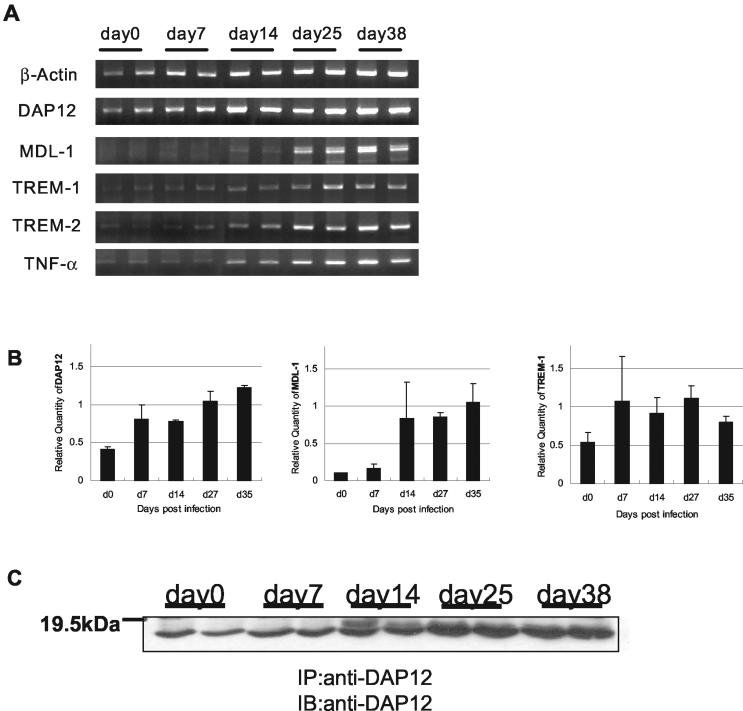

To investigate whether DAP12 and its associating molecules were involved in host defense against mycobacterial infection, expression of these molecules was examined in a mouse model of pulmonary mycobacterial infection (28, 29, 31, 33). At various time points after mycobacterial infection, mRNA expression of DAP12 and its associating molecules in the lung tissue was examined by RT-PCR and real-time quantitative PCR. DAP12 was constitutively expressed at a significant level in lung tissues prior to infection, and its expression started to increase from day 14 postinfection (Fig. 1A and B). Consistent with increased mRNA expression induced by mycobacterial infection, the constitutive level of DAP12 protein in the lungs was up-regulated around day 14 and continued to increased until day 38 postinfection as determined by using Western blotting (Fig. 1C). In comparison, the DAP12-associating molecules TREM-1 and TREM-2 were expressed constitutively in the lungs at much lower levels prior to infection and the expression of MDL-1 was hardly detectable until day 7 postinfection (Fig. 1A and B). However, the mRNA expression levels of all DAP12-associating molecules examined were highly induced by mycobacterial infection, being increased around day 14 and peaking between days 25 and 38. The MDL-1 mRNA has two bands, probably due to the presence of alternative polyadenylation sites in the gene (4).

FIG. 1.

(A) In vivo mRNA expression of DAP12 and associating molecules in lung tissue during mycobacterial infection. mRNA expression was examined by RT-PCR at the indicated time points after BCG infection (two C57BL/6 mice per time point). (B) Relative quantity of mRNA of DAP12 and associating molecules in the lung tissue during mycobacterial infection. Quantitation was carried out, relative to the expression of the GAPDH housekeeping gene by real-time quantitative PCR with the same total RNA samples as for the experiment in panel A. (C) Detection of DAP12 protein in the lung tissue during mycobacterial infection. Tissue lysates from each mouse lung (2 mg) were immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-DAP12 antibodies and analyzed by Western blotting (IB) using anti-DAP12 antibody. Representative results from two separate experiments are shown.

Relationship between DAP12-associating-molecule expression and type 1 cytokine induction in the lungs of wild-type mice during mycobacterial infection.

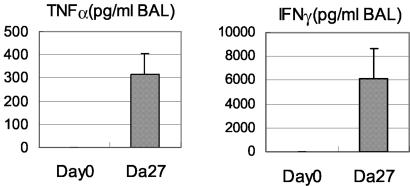

Since we have previously found that type 1 cytokines including TNF-α and IFN-γ are markedly induced in the course of pulmonary mycobacterial infection (28, 29), we investigated the temporal relationship between DAP12-associating-molecule expression and cytokine induction. Indeed, by RT-PCR, TNF-α mRNA expression was also markedly induced on day 14 and peaked after day 25, coinciding with the peak expression of DAP12 and associating molecules (Fig. 1A and B). On examination of protein levels by ELISA, we measured high levels of both TNF-α and IFN-γ in the lungs on day 27 postinfection (Fig. 2), similar to the levels that we detected in our previous studies (28, 29).

FIG. 2.

Levels of type 1 cytokines in the lungs of C57BL/6 mice on day 27 postinfection. The levels of type 1 cytokines in the lungs were determined by ELISA of samples of BAL fluids. Results are expressed as means and standard errors of the mean for three to four mice per time point.

Regulation of DAP12-associating-molecule expression by mycobacterial infection and type 1 cytokines in wild-type lung macrophages in vitro.

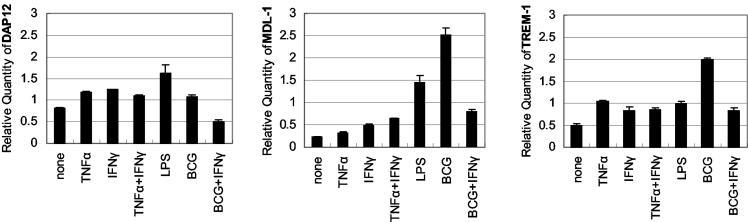

Macrophages are the primary cellular target of mycobacteria (32), and are also a rich source of DAP12-associating-molecule expression (1, 4, 15, 21). Hence, to dissect the factors that may regulate the expression of DAP12 and its associating molecules during lung mycobacterial infection, we examined the effect of M. bovis BCG bacilli and/or type 1 cytokines on the expression of DAP12 and its associating molecules in lung macrophages. Lung macrophages were isolated from the lungs of naive C57BL/6 mice and cultured with or without BCG bacilli, type 1 cytokine, or both. Expression of DAP12 and its associating molecules was examined by RT-PCR or real-time quantitative PCR. We focused on the use of TNF-α and IFN-γ, since both were shown to play an important role in host defense against mycobacterial infection (14, 18) and their expression pattern coincided with that of DAP12 and its associating molecules (Fig. 1 and 2) (28). Resting macrophages constitutively expressed considerable levels of DAP12 and TREM-2 but low levels of MDL-1 and TREM-1 (Fig. 3; data for TREM-2 not shown). In contrast to its increase in the lungs, expression of DAP12 (Fig. 3) and TREM-2 (data not shown) was not significantly altered in cultured macrophages on stimulation by mycobacteria or cytokines. In comparison, both MDL-1 and TREM-1 were induced severalfold from the base level in macrophages on mycobacterial infection (Fig. 3). Addition of LPS or type 1 cytokine TNF-α or IFN-γ (alone or in combination) also increased the expression of MDL-1 and TREM-1. To further mimic what may be happening in vivo during pulmonary mycobacterial infection, where macrophages are simultaneously exposed to mycobacteria and type 1 cytokines, macrophages were concurrently exposed to both mycobacteria and IFN-γ (exogenous TNF-α was not given since we previously reported that mycobacterially infected macrophages release a lot of TNF-α but little IFN-γ [30]). Of interest, IFN-γ markedly inhibited mycobacterially induced MDL-1 and TREM-1 expression (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Regulation of DAP12 and associating-molecule mRNA expression in lung macrophages by various stimuli. Isolated lung macrophages from naive C57BL/6 mice were incubated with live BCG bacilli, LPS, TNF-α, IFN-γ or a combination of TNF-α and IFN-γ or BCG and IFN-γ for 40 h and then examined by real-time quantitative PCR (TNF-α or IFN-γ, 5 ng/ml; LPS, 1 μg/ml; BCG, 2 CFU/cell). Gene expression was quantitated relative to the expression of GAPDH. Similar results were also obtained by RT-PCR (data not shown). Representative results from three separate experiments are shown.

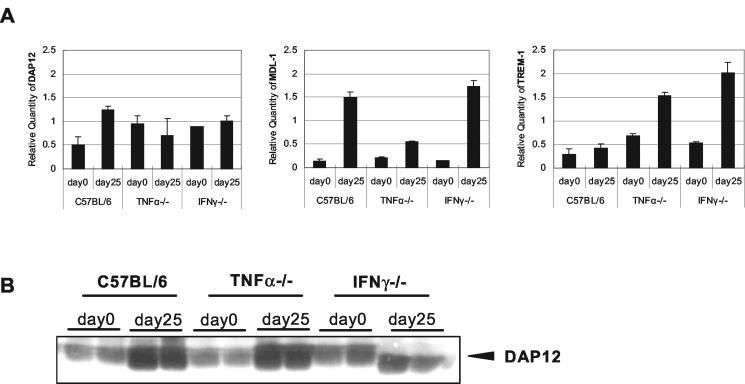

Regulation of DAP12-associating-molecule expression by mycobacterial infection and type 1 cytokines in the lungs of TNF-α- and IFN-γ-deficient mice.

To further evaluate the regulatory effect of mycobacteria and TNF-α and/or IFN-γ on DAP12 and its associating molecules in vivo, we infected wild-type C57BL/6, TNF-α−/− and IFN-γ−/− mice with M. bovis BCG and then examined the expression of these molecules in the lungs on day 25 postinfection by real-time quantitative PCR. Compared to wild-type control C57BL/6 mice, mice deficient in TNF-α had remarkably reduced expression of MDL-1 in the lungs during mycobacterial infection whereas the level of DAP12 and TREM-1 expression was not affected (Fig. 4A), suggesting that TNF-α is critically required for induction of MDL-1, but not DAP12 and TREM-1 molecules, during mycobacterial infection. Compared to both wild-type C57BL/6 and TNF-α-deficient mice, IFN-γ-deficient mice demonstrated the highest level of induction of MDL-1 and TREM-1 expression (Fig. 4A). These findings support a suppressive effect of IFN-γ on MDL-1 and TREM-1 expression during mycobacterial infection, as also observed in BCG- and IFN-γ-treated macrophages (Fig. 3). At the protein production level, the changes in DAP12 protein levels in the lungs of infected wild-type and IFN-γ−/− mice mirrored those at its mRNA expression level, with the exception that DAP12 protein production in TNF-α−/− mouse lungs was increased on infection (Fig. 4B).

FIG. 4.

Role of TNF-α and IFN-γ in the regulation of DAP12 and its associating molecule expression in the lungs during mycobacterial infection. (A) Expression of DAP12 and associating molecules in the lungs of C57BL/6, TNF-α−/−, and IFN-γ−/− mice. Mice were infected with 0.5 × 106 CFU of BCG intratracheally and sacrificed on day 25 postinfection. The lungs were examined by real-time quantitative PCR (two mice per strain per time point). Gene expression was quantitated relative to the expression of GAPDH. Similar results were also obtained by RT-PCR (data not shown). (B) Detection of DAP12 protein in the lungs of C57BL/6, TNF-α−/−, and IFN-γ−/− mice during mycobacterial infection. Tissue lysates (1.5 mg) from each mouse lung were immunoprecipitated with anti-DAP12 antibodies and analyzed by Western blotting. Representative results of two separate experiments are shown.

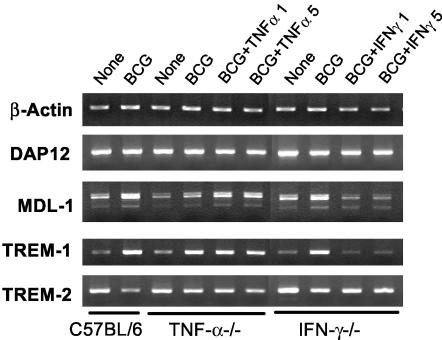

Regulation of DAP12-associating-molecule expression by mycobacterial infection and type 1 cytokines in TNF-α- and IFN-γ-deficient lung macrophages in vitro.

To evaluate the role of TNF-α and IFN-γ in the mycobacterially induced expression of DAP12 and associating molecules in lung macrophages, we set up cultures of lung macrophages isolated from naive TNF-α−/− or IFN-γ−/− mice and examined the expression of these molecules by RT-PCR. Compared to wild-type control lung macrophages, the presence or absence of TNF-α or IFN-γ or mycobacteria had relatively little effect on both DAP12 and TREM-2 expression (Fig. 5). However, while the lack of TNF-α diminished mycobacterially-induced MDL-1, reconstitution of this cytokine restored the level of MDL-1 expression. This is in agreement with our findings in the lungs of TNF-α-deficient mice (Fig. 4) and further suggests that endogenous TNF-α is required for optimal MDL-1 expression during mycobacterial infection. In contrast, while the lack of IFN-γ had relatively little effect on MDL-1 and TREM-1 induction by mycobacteria, addition of this cytokine markedly reduced MDL-1 and TREM-1 expression (Fig. 5). This finding is in agreement with our findings that exogenous IFN-γ inhibited mycobacterially induced MDL-1 and TREM-1 expression in wild-type lung macrophages (Fig. 3) and that infected IFN-γ−/− hosts demonstrated higher levels of MDL-1 and TREM-1 expression (Fig. 4A). Together, these findings indicate that TNF-α is selectively required for optimal expression of certain DAP12-associating molecules (MDL-1) whereas IFN-γ acts as a negative regulator of DAP12-associating molecules during mycobacterial infection.

FIG. 5.

Role of TNF-α and IFN-γ in the regulation of DAP12 and associating molecules in lung macrophages during in vitro mycobacterial infection. Isolated lung macrophages from naive C57BL/6, TNF-α−/−, and IFN-γ−/− mice were incubated with BCG and/or the indicated cytokines (1 or 5 ng/ml) for 40 h and then examined by RT-PCR. The experiments were repeated twice, with similar results, and representative results are shown.

DISCUSSION

The mycobacterium is a facultative intracellular pathogen of macrophages, and the signals involved in the activation of macrophage mycobactericidal activities still remain to be fully understood (27, 32). DAP12 and its associating MDL-1, TREM-1, and TREM-2 molecules are a group of novel immune regulatory molecules expressed primarily on macrophages, dendritic cells, and neutrophils (4, 7, 9). However, little is known about the regulation of their expression and whether they play a role in host responses to mycobacterial infection. In the present study, we have demonstrated that DAP12 is constitutively expressed in the lungs and that its is increased at both the mRNA and protein levels during mycobacterial infection. In comparison, DAP12-associating molecules, particularly MDL-1, are expressed constitutively at very low levels but are highly induced in the lungs during mycobacterial infection. The kinetics of such expression is closely associated with that of the type 1 cytokines TNF-α and IFN-γ, suggesting that these cytokines are involved in the regulation of expression of DAP12 and its associating molecules during mycobacterial infection. Indeed, by using TNF-α−/− and IFN-γ−/− mice or lung macrophages derived from these mice, we found that TNF-α and IFN-γ had a differential regulatory effect on expression of some but not all of DAP12 and associating molecules. In this regard, TNF-α and IFN-γ have no effect on the mycobacterially induced expression of DAP12 and TREM-2. However, TNF-α is required for mycobacterially induced MDL-1 expression while it has little effect on TREM-1 expression. In contrast, IFN-γ suppresses the mycobacterially induced expression of MDL-1 and TREM-1. These findings suggest that the expression of DAP12 and associating molecules is tightly regulated in host antimicrobial responses by both pathogen and host immune molecules such as cytokines and that the DAP12 signaling pathway triggered by MDL-1 and TREM-1 may play an important role in antimicrobial type 1 immunity. Since M. bovis BCG is an attenuated Mycobacterium strain, it is of interest to further investigate the regulation of DAP12 family members during virulent mycobacterial infection.

DAP12 is a transmembrane signaling molecule with an ITAM in its intracytoplasmic domain (19, 25). The signaling cascade mediated by DAP12 is thought to be triggered by a group of DAP12-associating cell surface molecules including MDL-1, TREM-1, and TREM-2 (4, 7, 11, 15, 17). Currently, the identities of almost all of the ligands for these molecules still remain unclear (3, 12, 16). The fact that DAP12 is expressed constitutively at high levels both in the lung tissue and in resting lung macrophages suggests that the focal point for controlling the DAP12 signaling pathway lies primarily in the relative level and availability of DAP12-associating molecules. Our findings that normal lungs expressed very low levels of DAP12-associating molecules, particularly MDL-1; whereas mycobacterially infected lungs expressed high levels of these molecules support such notion.

We observed that while DAP12, MDL-1, TREM-1, and TREM-2 levels were all increased in lung tissue during mycobacterial infection, only MDL-1 and TREM-1 were inducible in lung macrophage cultures by mycobacterial infection. Furthermore, the expression of MDL-1 and TREM-1, but not DAP12 and TREM-2, was tightly regulated by the macrophage-activating cytokines TNF-α and IFN-γ both in vivo and in vitro. Since the host tissue response to mycobacterial infection is characterized by macrophage granuloma formation, which peaks between days 25 and 38 in our model (29) and coincides with peak expression of DAP12 family molecules, our present findings suggest that the increased expression of DAP12 and TREM-2 in the lungs is a result of increased accumulation of macrophages in the lungs and argue against the true inducibility of these two molecules. Alternatively, the activation events leading to DAP12 and TREM-2 expression in the monocytes newly recruited into lung granulomas and in resident lung macrophages may differ, or there could be cellular sources other than macrophages for these two molecules. On the other hand, macrophages are very likely to be the primary cellular source of enhanced expression of MDL-1 and TREM-1 in lung tissue during infection. Although at this time we could evaluate the protein production only for DAP12 (detection antibodies to other molecules are not yet available), the close correlation between changes in DAP12 mRNA and protein levels suggests that changes in the mRNA expression of other molecules are also reflective of the corresponding protein production.

Colonna and Facchetti have recently reported that TREM-1 was expressed in human lung macrophages but was not found in tuberculous granuloma in human lung tissues (13). In comparison, we found TREM-1 expression both in lung macrophages and in tissues. It is possible that TREM-1 expression is related to the distinct stage of mycobacterial granulomatous responses, and it would be difficult to carry out kinetic studies by using human tissue samples. Bleharski et al. reported the up-regulation of TREM-1 expression in human monocytes by various stimuli including the M. tuberculosis 19-kDa protein (ligand for TLR2) and LPS (ligand for TLR4) in the presence of TNF-α or granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (6). However, in our model systems of mycobacterial infection, we found that TNF-α was critically required for MDL-1, but not TREM-1, expression in the lungs and macrophages during mycobacterial infection. This could be due to a distinct difference in the model system that we employed, which involved live intracellular bacterial infection. Nonetheless, the findings by Bleharski et al. and ourselves do suggest that regulation of DAP12 family molecule expression involves multiple signals of both microbial and cytokine types. Caution should, however, be exercised during interpretation of the effect of cytokines on the expression of DAP12 family molecules in the absence of microbial agents. For instance, we found that IFN-γ alone enhanced macrophage expression of MDL-1 and TREM-1 but inhibited mycobacterially induced MDL-1 or TREM-1 expression. While the mechanisms by which IFN-γ controls MDL-1 expression remain speculative, IFN-γ has been shown to have an inhibitory effect on gene expression of certain molecules in macrophages/monocytes via induction of inducible cyclic AMP early repressor (ICER) (20).

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research and the Ontario government.

We are indebted to the invaluable technical assistance provided by Min Li.

Editor: S. H. E. Kaufmann

REFERENCES

- 1.Aoki, N., S. Kimura, Y. Takiyama, Y. Atsuta, A. Abe, K. Sato, and M. Katagiri. 2000. The role of the DAP12 signal in mouse myeloid differentiation. J. Immunol. 165:3790-3796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aoki, N., S. Kimura, K. Oikawa, H. Nochi, Y. Atsuta, H. Kobayashi, K. Sato, and M. Katagiri. 2002. DAP12 ITAM motif regulates differentiation and apoptosis in M1 leukemia cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 291:296-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aoki, N., S. Kimura, and Z. Xing. 2003. Role of DAP12 in innate and adaptive immune responses. Curr. Pharm. Des. 9:7-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bakker, A. B., E. Baker, G. R. Sutherland, J. H. Phillips, and L. L. Lanier. 1999. Myeloid DAP12-associating lectin (MDL)-1 is a cell surface receptor involved in the activation of myeloid cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:9792-9796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bakker, A. B., R. M. Hoek, A. Cerwenka, B. Blom, L. Lucian, T. McNeil, R. Murray, L. H. Phillips, J. D. Sedgwick, and L. L. Lanier. 2000. DAP12-deficient mice fail to develop autoimmunity due to impaired antigen priming. Immunity 13:345-353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bleharski, J. R., V. Kiessler, C. Buonsanti, P. A. Sieling, S. Stenger, M. Colonna, and R. L. Modlin. 2003. A role for triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-1 in host defense during the early induced and adaptive phases of the immune response. J. Immunol. 170:3812-3818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bouchon, A., J. Dietrich, and M. Colonna. 2000. Inflammatory responses can be triggered by TREM-1, a novel receptor expressed on neutrophils and monocytes. J. Immunol. 164:4991-4995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bouchon, A., F. Facchetti, M. A. Weigand, and M. Colonna. 2001. TREM-1 amplifies inflammation and is a crucial mediator of septic shock. Nature 410:1103-1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bouchon, A., C. Hernandez-Munain, M. Cella, and M. Colonna. 2001. A DAP12-mediated pathway regulates expression of CC chemokine receptor 7 and maturation of human dendritic cells. J. Exp. Med. 194:1111-1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cantoni, C., C. Bottino, M. Vitale, A. Pessino, R. Augugliaro, A. Malaspina, S. Parolini, L. Moretta, A. Moretta, and R. Biassoni. 1999. NKp44, a triggering receptor involved in tumor cell lysis by activated human natural killer cells, is a novel member of the immunoglobulin superfamily. J. Exp. Med. 189:787-795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chung, D. H., W. E. Seaman, and M. R. Daws. 2002. Characterization of TREM-3, an activating receptor on mouse macrophages: definition of a family of single Ig domain receptors on mouse chromosome 17. Eur. J. Immunol. 32:59-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Colonna, M. 2003. TREMs in the immune system and beyond. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 3:445-453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Colonna, M., and F. Facchetti. 2003. TREM-1 (triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells): a new player in acute inflammatory responses. J. Infect. Dis. 187:S397-S401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cooper, A. M., D. K. Dalton, T. A. Stewart, J. P. Griffin, D. G. Russell, and I. M. Orme. 1993. Disseminated tuberculosis in interferon gamma gene-disrupted mice. J. Exp. Med. 178:2243-2247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Daws, M. R., L. L. Lanier, W. E. Seaman, and J. C. Ryan. 2001. Cloning and characterization of a novel mouse myeloid DAP12-associated receptor family. Eur. J. Immunol. 31:783-791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Daws, M. R., P. M. Sullam, E. C. Niemi, T. T. Chen, N. K. Tchao, and W. E. Seaman. 2003. Pattern recognition by TREM-2: binding of anionic ligands. J. Immunol. 171:594-599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dietrich, J., M. Cella, M. Seiffert, H. J. Buhring, and M. Colonna. 2000. Signal-regulatory protein beta 1 is a DAP12-associated activating receptor expressed in myeloid cells. J. Immunol. 164:9-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Flynn, J. L., M. M. Goldstein, J. Chan, K. J. Triebold, K. Pfeffer, C. J. Lowenstein, R. Schreiber, T. W. Mak, and B. R. Bloom. 1995. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha is required in the protective immune response against Mycobacterium tuberculosis in mice. Immunity 2:561-572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lanier, L. L., B. C. Corliss, J. Wu, C. Leong, and J. H. Phillips. 1998. Immunoreceptor DAP12 bearing a tyrosine-based activation motif is involved in activating NK cells. Nature 391:703-707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mead, J. R., T. R. Hughes, S. A. Irvine, N. N. Singh, and D. P. Ramji. 2003. Interferon-γ stimulates the expression of the inducible cAMP early repressor in macrophages through the activation of casein kinase 2. J. Biol. Chem. 278:17741-17751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nochi, H., N. Aoki, K. Oikawa, M. Yanai, Y. Takiyama, Y. Atsuta, H. Kobayashi, K. Sato, M. Tateno, T. Matsuno, M. Katagiri, Z. Xing, and S. Kimura. 2003. Modulation of hepatic granulomatous responses by transgene expression of DAP12 or TREM-1-Ig molecules. Am. J. Pathol. 162:1191-1201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Olcese, L., A. Cambiaggi, G. Semenzato, C. Bottino, A. Moretta, and E. Vivier. 1997. Human killer cell activatory receptors for MHC class I molecules are included in a multimeric complex expressed by natural killer cells. J. Immunol. 158:5083-5086. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ritz, S. A., M. J. Cundall, B. U. Gajewska, D. Alvarez, J. C. Gutierrez-Ramos, A. J. Coyle, A. N. McKenzie, M. R. Stampfli, and M. Jordana. 2002. Granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor-driven respiratory mucosal sensitization induces Th2 differentiation and function independently of interleukin-4. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 27:428-435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sjolin, H., E. Tomasello, M. Mousavi-Jazi, A. Bartolazzi, K. Karre, E. Vivier, C. Cerboni, et al. 2002. Pivotal role of KARAP/DAP12 adaptor molecule in the natural killer cell-mediated resistance to murine cytomegalovirus infection. J. Exp. Med. 195:825-834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tomasello, E., L. Olcese, F. Vely, C. Geourgeon, M. Blery, A. Moqrich, D. Gautheret, M. Djabali, M. G. Mattei, E. Vivier. 1998. Gene structure, expression pattern, and biological activity of mouse killer cell activating receptor-associated protein (KARAP)/DAP-12. J. Biol. Chem. 273:34115-34119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tomasello, E., P. O. Desmoulins, K. Chemin, S. Guia, H. Cremer, J. Ortaldo, P. Love, D. Kaiserlian and E. Vivier. 2000. Combined natural killer cell and dendritic cell functional deficiency in KARAP/DAP12 loss-of-function mutant mice. Immunity 13:355-364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Van Crevel, R., T. H. Ottenhoff, and J. W. van der Meer. 2002. Innate immunity to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 15:294-309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wakeham, J., J. Wang, J. Magram, K. Croitoru, R. Harkness, P. Dunn, A. Zganiacz, and Z. Xing. 1998. Lack of both type 1 and 2 cytokines, tissue inflammatory responses, and immune protection during pulmonary infection by Mycobacterium bacille Calmette-Guérin in IL-12-difecient mice. J. Immunol. 160:6101-6111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wakeham, J., J. Wang, and Z. Xing. 2000. Genetically determined disparate innate and adaptive cell-mediated immune response to pulmonary Mycobacterium bovis BCG infection in C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice. Infect. Immun. 68:6946-6953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang, J., J. Wakeham, R. Harkness, and Z. Xing. 1999. Macrophages are a significant source of type 1 cytokines during mycobacterial infection. J. Clin. Investig. 103:1023-1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xing, Z., J. Wang, K. Croitoru, and J. Wakeham. 1998. Protection by CD4 or CD8 T cells against pulmonary Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette-Guérin infection. Infect. Immun. 66:5537-5542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xing, Z. 2001. The hunt for new tuberculosis vaccines: anti-TB immunity and rational design of vaccines. Curr. Pharm. Des. 7:1015-1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xing, Z., A. Zganiacz, J. Wang, and S. K. Sharma. 2001. Enhanced protection against fatal mycobacterial infection in SCID beige mice by reshaping innate immunity with IFN-γ transgene. J. Immunol. 167:375-383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]