Abstract

Background

Migraine, a common chronic-intermittent disorder among reproductive age women, has emerged as a novel risk factor for adverse perinatal outcomes. Diagnostic reliability of self-report of physician-diagnosed migraine has not been investigated in pregnancy cohort studies. We investigated agreement of self-report of physician-diagnosed migraine with the diagnostic criteria promoted by the International Classification of Headache Disorders, 2nd edition (ICHD-II).

Methods

The cross-sectional study was conducted among 500 women who provided information on a detailed migraine questionnaire that allowed us to apply all ICHD-II diagnostic criteria.

Results

Approximately 92% of women reporting a diagnosis of migraine had the diagnosis between the ages of 11 and 40 years (<10 years 6.8%; 11–20 years 38.8%; 21–30 years 42.7%; 31–40 years 10.7%; and >40 years 1.0%). We confirmed self-reported migraine in 81.6% of women when applying the ICHD-II criteria for definitive migraine (63.1%) and probable migraine (18.5%).

Conclusion

There is good agreement between self-reported migraine and ICHD-II-based migraine classification in this pregnancy cohort. We demonstrate the feasibility of using questionnaire-based migraine assessment according to full ICHD-II criteria in epidemiological studies of pregnant women.

Keywords: Migraine, Pregnancy, Diagnosis, ICHD-II, Self-report, Agreement

Background

Migraine, a common chronic-intermittent neurovascular headache disorder, is ranked among the world’s twenty most disabling medical conditions by the World Health Organization [1]. Migraine is characterized by episodic severe headache accompanied by autonomic nervous system dysfunction. Women are more commonly affected than men, with reported lifetime prevalence estimates of 16-32% for women and 6-9% for men [2-6]. Migraine risk varies considerably across the life course. The prevalence of migraine in women rises after the average age of menarche, and peaks before the average age of menopause [7]. Thus migraines are most prevalent among women in their childbearing years.

Migraine has emerged as a novel risk factor for adverse perinatal outcomes including hypertensive disorders of pregnancy [8,9], preterm birth [10] and placental abruption [11]. Most prior epidemiologic studies have relied on self-report of physician-diagnosed migraine as a means for classifying pregnant women with a history of migraine. Data from the Women’s Health Study (a study of women aged ≥ 45 years) showed very good agreement between self-reported migraine and ICHD-II-based diagnosed migraine. The investigators confirmed self-reported migraine in > 87% of women when applying the International Classification of Headache Disorders 2004 criteria (ICHD-II) for definitive migraine (71.5%) and probable migraine (16.2%) without aura [12]. We are unaware of studies that investigated diagnostic reliability (commonly measured using inter-rater agreement) of self-report of physician-diagnosed migraine in pregnancy cohort studies.

In a cross-sectional study, we investigated 500 pregnant women who provided information on a detailed migraine questionnaire that allowed us to apply ICHD-II diagnostic criteria, promoted by International Headache Society (IHS), and examined the agreement of self-reported physician diagnosis of migraine with migraine determined using the ICHD-II diagnostic criteria (“golden standard”) in this report.

Methods

Study participants were pregnant women attending prenatal care at clinics affiliated with Swedish Medical Center in Seattle, Washington and enrolled in the Migraine and Pregnancy Study, a pregnancy cohort study designed to investigate the relationship between migraine, headache symptoms before and during pregnancy, and the risk of preeclampsia [13]. The study population for this report is from the first 500 participants who were enrolled (consecutively) and were interviewed during the period of April 2009 and December 2010. Women were ineligible if they initiated prenatal care after 20 weeks gestation, were younger than 18 years of age, did not speak and read English, did not plan to carry the pregnancy to term, or did not plan to deliver at Swedish Medical Center. Participants completed a questionnaire administered by trained interviewers (supervised by neurologist and maternal fetal medicine clinicians) at enrollment. Participants were asked to provide information pertaining to their medical history, pre-pregnancy weight, general health, pregnancy-related symptoms, socio-demographic, and lifestyle characteristics. The interview included a structured migraine assessment questionnaire (adapted from the deCODE Genetics migraine questionnaire (DMQ3) [14] (Additional file 1) and an assessment of disability associated with headaches experienced before and during pregnancy by Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS) Questionnaire [15]. In previous validation study, using a physician-conducted interview as an empirical index of validity, the deCODE Migraine Questionnaire (DMQ3) diagnosed migraine with a sensitivity of 99%, a specificity of 86% and a kappa statistic of 0.89 [16]. The detailed migraine-specific questionnaire contained questions addressing age at migraine onset, physician diagnosis of migraine, family history of migraine, details about migraine attacks and medication used.

Headache classification was determined using the ICHD-II criteria established by the International Headache Society (IHS) [17]. “Definitive Migraine” (IHS category 1.1 or 1.2) was defined by at least five lifetime headache attacks (criterion A) lasting 4–72 hours (criterion B), with at least two of the qualifying pain characteristics [unilateral location (criterion C1), pulsating quality (criterion C2), moderate or severe pain intensity (criterion C3), aggravation by routine physical exertion (criterion C4)]; at least one of the associated symptoms [nausea and/or vomiting (criterion D1), photo/phonophobia (criterion D2)]; and not readily attributable to another central nervous system disorder or head trauma (according to subject self-report) (criterion E). “Probable Migraine” (IHS category 1.6) was designated if all but one of the definitive migraine criteria were fulfilled, excluding headaches attributable to another disorder. Finally, any migraine was defined as the group with either definitive migraine or probable migraine combined.

The procedures used in the study were in agreement with the protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board of Swedish Medical Center (Swedish IRB # 008567). All participants provided written informed consent.

Frequency distributions of sociodemographic, reproductive, medical and behavioral factors among groups defined by ICHD-II (any migraine, no migraine) and the cohort were compared using means (± standard deviation (SD)) for continuous variables and counts and percentages for categorical variables. Bivariate differences in characteristics associated with definitive and probable migraine headaches were determined using Chi-square test (or Fisher’s exact test) for categorical variables and Student’s t-test for continuous variables.

The self-reported physician migraine diagnosis was compared with the ICHD-II based diagnosis. The sensitivity and specificity as well as positive predictive value and negative predictive value of the self-reported diagnosis were assessed. Concordance also was determined by estimating the value of Cohen’s kappa coefficient [18]. All analyses were performed using Stata 9.0 (Stata, College Station, TX) statistical analysis software. All reported p-values are two-tailed. The 95% confidence interval (CI) for the prevalence estimate of migraine was determined using previously described methods [19].

Results

A total of 100 subjects met the ICHD-II criteria for definitive migraine, and 49 additional subjects met the criteria for probable migraine. The lifetime prevalence of definitive migraine was 20.0% (95% CI 16.6-23.8%). When probable migraine was included, the lifetime prevalence of migraine in this population increased to 29.8% (95% CI 25.9-34.0%). However, chronic migraine, defined as headache that occurs 15 or more days a month with headache lasting 4 hours or longer for at least 3 consecutive months in individuals with current or prior diagnosis of migraine, occurred only in 12 women out of 149 ICHD-II diagnosed migraine cases.

Characteristics of participants according to ICHD-II-defined migraine status are presented in Table 1. A positive family history of migraine (defined as report of migraine for at least one of the following relatives: father, mother, sibling, grandparents, children) was reported by 65.1% of participants with migraine and by 35.0% of individuals without migraine. Participants with migraine tended to have higher pre-pregnancy body mass index and were more likely to report a positive history of chronic hypertension.

Table 1.

Maternal characteristics of study population according to ICHD-II criteria migraine (definitive + probable), April 2009-Dec 2010, Seattle, WA

| Characteristics |

Cohort

|

ICHD-II criteria for migraine (definitive + probable)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 500) | Yes (N = 149) | No (N = 351) | p-value | |

| Maternal Age (years) |

33.4 ± 4.2 |

32.9 ± 4.4 |

33.6 ± 4.1 |

0.131 |

| Maternal Age (years) | ||||

| < 35 |

316 (63.2) |

102 (68.5) |

214 (61.0) |

0.112 |

| ≥ 35 |

184 (36.8) |

47 (31.5) |

137 (39.0) |

|

| Maternal Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White |

430 (86.0) |

126 (84.6) |

304 (86.6) |

0.593 |

| African American |

8 (1.6) |

4 (2.7) |

4 (1.1) |

|

| Other |

57 (11.4) |

18 (12.1) |

39 (11.1) |

|

| Missing |

5 (1.0) |

1 (0.7) |

4 (1.1) |

|

| Annual Household Income ($) | ||||

| <50,000 |

20 (4.0) |

6 (4.0) |

14 (4.0) |

0.061 |

| 50,000-69,000 |

33 (6.6) |

13 (8.7) |

20 (5.7) |

|

| ≥ 70,000 |

428 (85.6) |

129 (86.6) |

299 (85.2) |

|

| Missing |

19 (3.8) |

1 (0.7) |

18 (5.1) |

|

| Single Marital Status |

48 (9.6) |

19 (12.8) |

29 (8.3) |

0.119 |

| Nulliparous |

261 (52.2) |

81 (54.4) |

180 (51.3) |

0.528 |

| Unplanned Pregnancy |

72 (14.4) |

24 (16.1) |

48 (13.7) |

0.479 |

| Cigarette Smoker during early pregnancy |

95 (19.0) |

30 (20.1) |

65 (18.5) |

0.674 |

| Family History of Headache/Migraine |

220 (44.0) |

97 (65.1) |

123 (35.0) |

<0.001 |

| History of Chronic Hypertension |

11 (2.2) |

7 (4.7) |

4 (1.1) |

0.020 |

| Pre-Pregnancy Body Mass Index (kg/m2) |

23.5 ± 4.7 |

24.7 ± 5.4 |

23.0 ± 4.3 |

<0.001 |

| Pre-Pregnancy Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | ||||

| <18.5 |

24 (4.8) |

5 (3.4) |

19 (5.4) |

0.012 |

| 18.5-24.9 |

340 (68.0) |

89 (59.7) |

251 (71.5) |

|

| 25.0-29.9 |

92 (18.4) |

34 (22.8) |

58 (16.5) |

|

| ≥ 30.0 |

42 (8.4) |

20 (13.4) |

22 (6.3) |

|

| Missing | 2 (0.4) | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.3) | |

Data in mean ± standard deviation (SD) or number (%).

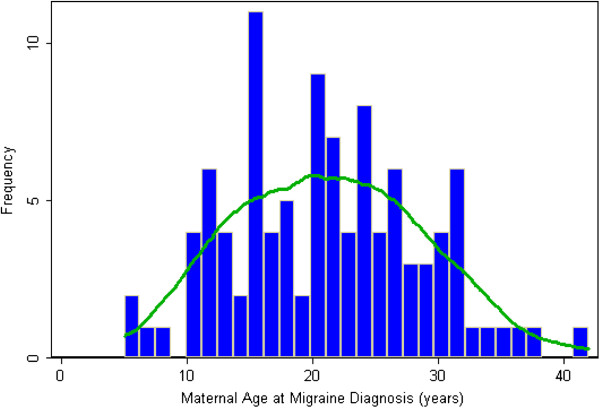

We confirmed self-reported migraine in 81.6% of women when applying the ICHD-II criteria for definitive migraine (63.1%) and probable migraine (18.5%) (Table 2). Overall, when compared to the ICHD-II diagnosis, the self-reported physician diagnosis had a sensitivity of 56.8% (95% CI 48.7%-64.5%); a specificity of 94.6% (95% CI 91.7%-96.5%) and positive predictive value of 81.6% (95% CI 73.0%-87.9%), as well as negative predictive value of 83.8% (95% CI 79.8%-87.1%). Cohen’s kappa coefficient was 0.56. We did not observe differences in Choen’s kappa coefficients when analyses were stratified by parity (i.e., nulliparous vs. multiparous). Characteristics such as nausea and/or vomiting and photophobia were far more prevalent among women who reported having a physician diagnosis of migraine as compared with their counterparts without such a diagnosis. Approximately 92% of women reporting a diagnosis of migraine had the diagnosis between the ages of 11 and 40 years (<10 years 6.8%; 11–20 years 38.8%; 21–30 years 42.7%; 31–40 years 10.7%; and >40 years 1.0%) (Figure 1).

Table 2.

Summary of self-reported migraine and ICHD-II classified migraine

| Characteristics |

Self-reported migraine |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Yes |

No |

|

| (N = 103) | (N = 395) | |

| ICHD-II Diagnostic Criteria: Migraine | ||

| No |

19 (18.5) |

331 (83.8) |

| Yes |

84 (81.6) |

64 (16.2) |

| ICHD-II criteria migraine (probable) |

19 (18.5) |

29 (7.3) |

| ICHD-II criteria migraine (definitive) |

65 (63.1) |

35 (8.9) |

| Lifetime number of headache/migraine attacks ≥5 (criterion A) |

95 (92.2) |

94 (23.8) |

| Attacks lasting 4–72 hours (criterion B) |

80 (77.7) |

73 (18.5) |

| Unilateral headache location (criterion C1) |

59 (57.3) |

43 (10.9) |

| Pulsating pain quality (criterion C2) |

62 (60.2) |

60 (15.2) |

| Moderate or severe pain intensity (criterion C3) |

95 (92.2) |

101 (25.6) |

| Aggravation by routine physical activity (criterion C4) |

72 (69.9) |

70 (17.7) |

| Nausea and/or vomiting (criterion D1) |

80 (77.7) |

64 (16.2) |

| Photophobia |

91 (88.4) |

90 (22.8) |

| Phonophobia |

86 (83.5) |

79 (20.0) |

| Photo- and phonophobia (criterion D2) | 82 (79.6) | 66 (16.7) |

2 subjects missing self-reported migraine information.

Data in number (%).

ICHD-II, International Classification of Headache Disorders, version 2 (ICHD-II).

Figure 1.

Frequency distribution and Kernel density plot of maternal age at self-reported migraine diagnosis.

Discussion

Our study finding of a high prevalence (29.8%) of migraine in this cohort of pregnant women of reproductive age is consistent with prior literature [3-5]. For example, the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention (AMPP) Study found that the highest 1-year period prevalence was observed among those ages 18–59. In that cohort, 17.1% of women met diagnostic criteria for definitive migraine; and additional 5.1% met diagnostic criteria for probable migraine [5]. Our study also showed good agreement between self-reported migraine and ICHD-II-based migraine classification. Our results were consistent with reports by Schurks et al., who reported good agreement between self-reported migraine and ICHD-II defined migraine in a cohort of non-pregnant women [12]. Since migraine diagnosis relies on the presence of certain symptoms as well as associated features, information that can easily be obtained using questionnaires, the agreement of such self-reports with the ICHD-II criteria is crucial for studying migraine-specific characteristics in population-based epidemiological studies.

The strengths of our study include the relatively large number of women with information from the detailed standardized questionnaire allowing us to apply all ICHD-II criteria for migraine, and the opportunity to compare with self-reported “physician-diagnosed” migraine information. To our best knowledge, this is the first study that investigated the agreement of self-reported migraine with ICHD-II diagnosis in a pregnancy cohort. Pregnancy is a unique condition. During the first trimester, women experience increased physiological and psychological changes such as hormonal surge and increased blood volume. Lack of sleep, low blood sugar, dehydration and possible caffeine withdrawal could also contribute to the occurrence of migraine attacks. The headache may be further aggravated by stress [20,21]. In addition, there is a heightened cautiousness among women with regards to using medication during early pregnancy to prevent or treat their headaches. Concurrently, most studies on migraine in pregnancy detected a decrease in frequency of reported migraine attacks and pain intensity in the 2nd and 3rd trimesters as hormone levels stabilize [22-24].

Some important limitations must be considered when interpreting the results of our study. First, our ICHD-II-diagnosed migraine is based on questionnaires administered by trained interviewers instead of the gold standard of physician examination. However, it is not feasible to take implement full scale physical examinations with medical histories in large epidemiological studies, making our approach a practical alternative. In this study, we observed good agreement between ICHD-II diagnosed migraine and self-reported “physician diagnosed” migraine. Secondly, misclassification of headache type is possible. The questionnaire did not ask women to describe multiple headache types, and it is presumed that subjects described the headache episodes most burdensome to them. Misunderstanding one or more questions on the migraine-specific questionnaire may also lead to a misclassification according to the ICHD-II criteria. Third, caution must be taken that a diagnosis made during pregnancy may be attributable to transient changes in the characters of primitive headaches [25]; however, in the current study, 93.3% of ICHD-II defined migraine patients reported that their headache attacks started more than one year before the interview, hence mitigating concern of misclassification in this case. Finally, in this study, only a small minority of women with migraine were classified as having chronic migraine per se. Recall bias is possible although migraines are usually dramatic events well remembered by the affected persons.

Conclusions

There is good agreement between self-reported physician-diagnosed migraine and ICHD-II-based migraine classification in this pregnancy cohort. Our findings demonstrate the feasibility of using questionnaire-based migraine assessment according to full ICHD-II criteria in epidemiological studies of pregnant women.

Abbreviations

ICHD-II: The International Classification of Headache Disorders 2004 criteria, version II; IHS: International Headache Society; SD: Standard deviation; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval; AMPP: American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

MAW acquired funding for the study and developed the study design. SKA and BLP helped develop the study design. IOF monitored the data collection. CQ, DAE and MAW developed the analytical plan; CQ completed the statistical analysis. CQ, DAE, MAW drafted the manuscript. All authors edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Supplementary Material

The deCODE Genetics migraine questionnaire (DMQ3)

Contributor Information

Chunfang Qiu, Email: Chun-fang.Qiu@Swedish.org.

Michelle A Williams, Email: mawilliams84@gmail.com.

Sheena K Aurora, Email: saurora@stanford.edu.

B Lee Peterlin, Email: lpeterlin@jhmi.edu.

Bizu Gelaye, Email: mirtprogram@gmail.com.

Ihunnaya O Frederick, Email: Ihunnaya.Frederick@swedish.org.

Daniel A Enquobahrie, Email: danenq@u.washington.edu.

Acknowledgment

This research was supported by an award from the National Institutes of Health (R01HD-055566). The authors are indebted to the staff of the Center for Perinatal Studies for their expert technical assistance.

References

- World Health Organization. Headache disorders. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs277/en/ (accessed on April 2013)

- Steiner TJ, Scher AI, Stewart WF, Kolodner K, Liberman J, Lipton RB. The prevalence and disability burden of adult migraine in England and their relationships to age, gender and ethnicity. Cephalalgia. 2003;13:519–527. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.2003.00568.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National health and nutrition examination survey website. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes.htm (accessed December 17, 2012)

- Kalaydjian A, Merikangas K. Physical and mental comorbidity of headache in a nationally representative sample of US adults. Psychosom Med. 2008;13:773–780. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31817f9e80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipton RB, Bigal ME, Diamond M, Freitag F, Reed ML, Stewart WF. AMPP Advisory Group. Migraine prevalence, disease burden, and the need for preventive therapy. Neurology. 2007;13:343–349. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000252808.97649.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smitherman TA, Burch R, Sheikh H, Loder E. The prevalence, impact, and treatment of migraine and severe headaches in the United States: a review of statistics from national surveillance studies. Headache. 2013;13:427–436. doi: 10.1111/head.12074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nappi RE, Berga SL. Migraine and reproductive life. Handb Clin Neurol. 2010;13:303–322. doi: 10.1016/S0072-9752(10)97025-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simbar M, Karimian Z, Afrakhteh M, Akbarzadeh A, Kouchaki E. Increased risk of pre-eclampsia (PE) among women with the history of migraine. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2010;13:159–165. doi: 10.3109/10641960903254489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams MA, Peterlin BL, Gelaye B, Enquobahrie DA, Miller RS, Aurora SK. Trimester-specific blood pressure levels and hypertensive disorders among pregnant migraineurs. Headache. 2011;13:1468–1482. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2011.01961.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair EM, Nelson KB. Migraine and preterm birth. J Perinatol. 2011;13:434–439. doi: 10.1038/jp.2010.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez SE, Williams MA, Pacora PN, Ananth CV, Qiu C, Aurora SK, Sorensen TK. Risk of placental abruption in relation to migraines and headaches. BMC Womens Health. 2010;13:30. doi: 10.1186/1472-6874-10-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schürks M, Buring JE, Kurth T. Agreement of self-reported migraine with ICHD-II criteria in the Women’s Health Study. Cephalalgia. 2009;13:1086–1090. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2008.01835.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frederick IO, Qiu C, Enquobahrie DA, Aurora SK, Peterlin BL, Gelaye B, Williams MA. Lifetime prevalence and correlates of migraine among women in a pacific northwest pregnancy cohort study. Headache. 2013. Epub. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- deCODE Genetics. http://www.decode.com/migraine/questionnaire (for the English translation of the Icelandic, deCODE migraine questionnaire used in this study)

- Stewart WF, Lipton RB, Dowson AJ, Sawyer J. Development and testing of the Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS) Questionnaire to assess headache-related disability. Neurology. 2001;13:S20–S28. doi: 10.1212/WNL.56.suppl_1.S20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchmann M, Seven E, Björnsson A, Björnssdóttir G, Gulcher JR, Stefánsson K, Olesen J. Validation of the deCODE Migraine Questionnaire (DMQ3) for use in genetic studies. Eur J Neurol. 2006;13:1239–1244. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2006.01491.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache Society. The international classification of headache disorders, 2nd edition. Cephalalgia. 2004;13(Suppl 1):S5–S12. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2003.00824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Education Psychol Measure. 1960;13:37–46. doi: 10.1177/001316446002000104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Colton T. Statistics in medicine. Boston: Little, Brown and Company; 1974. p. P160. [Google Scholar]

- Andress-Rothrock D, King W, Rothrock J. An analysis of migraine triggers in a clinic-based population. Headache. 2010;13:1366–1370. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2010.01753.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milde-Busch A, Blaschek A, Heinen F, Borggräfe I, Koerte I, Straube A, Schankin C, von Kries R. Associations between stress and migraine and tension-type headache: results from a school-based study in adolescents from grammar schools in Germany. Cephalalgia. 2011;13:774–785. doi: 10.1177/0333102410390397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen TC, Leviton A. Headache recurrence in pregnant women with migraine. Headache. 1994;13:107–110. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.1994.hed3402107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharff L, Marcus DA, Turk DC. Headache during pregnancy and in the postpartum: a prospective study. Headache. 1997;13:203–210. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4610.1997.3704203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvisvik EV, Stovner LJ, Helde G, Bovim G, Linde M. Headache and migraine during pregnancy and puerperium: the MIGRA-study. J Headache Pain. 2011;13:443–451. doi: 10.1007/s10194-011-0329-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maggioni F, Alessi C, Maggino T, Zanchin G. Headache during pregnancy. Cephalalgia. 1997;13:756–759. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.1997.1707756.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The deCODE Genetics migraine questionnaire (DMQ3)