Abstract

In this work we expand upon a recently reported local drug delivery device, where air is used as a degradable component of our material to control drug release (J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 2016-2019). We consider its potential use as a drug loaded strip to provide both mechanical stability to the anastomosis, and as a means to release drug locally over prolonged periods for prevention of locoregional recurrence in colorectal cancer. Specifically, we electrospun poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL) with the hydrophobic polymer dopant poly(glycerol monostearate-co-ε-caprolactone) (PGC-C18) and used the resultant mesh to control the release of two anticancer drugs (CPT-11 and SN-38). The increase in mesh hydrophobicity with PGC-C18 addition slows drug release both by the traditional means of drug diffusion, as well as by increasing the stability of the entrapped air layer to delay drug release. We demonstrate that superhydrophobic meshes have mechanical properties appropriate for surgical buttressing of the anastomosis, permit non-invasive assessment of mesh location and documentation of drug release via ultrasound, and release chemotherapy over a prolonged period of time (>90 days) resulting in significant tumor cytotoxicity against a human colorectal cell line (HT-29).

Keywords: superhydrophobic, biomaterial, local drug delivery, electrospinning, colorectal cancer, recurrence

1. Introduction

An estimated 143,000 patients are diagnosed with colorectal cancer in the US each year, resulting in 51,000 deaths annually, making it the third leading cause of cancer death.[2] The standard of care for treatment of localized colorectal cancer is surgical resection.[3] However, of those patients receiving surgery with the intent to cure, up to 40% will develop locoregional recurrence depending on the location and aggressiveness of their disease.[4-5] Chemotherapy and radiation are not often pursued as adjuvant therapies to surgery with the goal of preventing locoregional recurrence in patients with early-stage disease, as the risk of systemic toxicity outweighs the potential benefit of such treatment in the overall population. This leaves few, if any, effective treatment options to decrease the risk of recurrent tumor in those patients that harbor occult disease. Hence, there is a significant clinical need to improve the standard of care for early-stage colorectal cancer patients in order to reduce the incidence of local tumor recurrence following surgery. One potential strategy to improve patient outcome is to couple surgical resection with a local drug delivery system whereby chemotherapy is delivered to the site at highest risk for recurrence – the site of resection of the primary tumor. Although reinforcement polymeric materials have been used experimentally to minimize post-surgery complications including leakage and rupture after bowel and upper GI surgery with limited success [6], we envision a dual-function device, amenable to implementation using current standard surgical techniques, to both reinforce the surgical margin as well as to locally elute drug to prevent locoregional tumor recurrence.

In general, drug delivery systems are used to optimize delivery of existing bioactive agents, such as those used in the treatment of colorectal cancer, by ‘repackaging’ them to achieve therapeutic doses at a target site, decrease systemic side effects, and alter the pharmacokinetic profile.[7-13] Two major classes of systems exist. The first, nano/micro-carriers, encapsulate a therapeutic agent for delivery, where the carrier aids in targeting the drug to a specific site using passive and/or active targeting mechanism(s).[14-17] These devices are traditionally particle-based (nano/microparticle, liposome, micelle, and dendrimers) and are designed to be delivered systemically by injection with their homing features aiding targeting to the desired site. The second class is an implantable drug depot, where macroscopic drug-loaded devices are implanted at the site of tumor in order to locally deliver drug to a target site, eliminating the need for targeting and migration from the bloodstream into the target tissue(s). Many types of implantable drug depots have been reported, including gels, rods, wafers, and films, all of which deliver a dose of drug directly to the target site.[18-19] Often, the mechanism of release from these devices is diffusion or degradation depending on the polymer system, where a hydrophobic drug embedded in a hydrophobic polymer releases over an extended period of time. Recently, we have demonstrated that implantable drug delivery films can effectively treat resected lung and sarcoma tumors [20-22], via a strategy of delivering low-dose chemotherapy over many cell cycles, and we hypothesized that a similar approach may be used to treat/prevent locoregional recurrence in colorectal cancer patients.

We recently published results on a novel implantable drug delivery system based on superhydrophobic electrospun meshes, where we demonstrated the ability to control and prolong delivery of a model bioactive molecule using controlled air displacement.[1] This electrospun system uses diffusion-based drug release, but adds secondary regulation of drug release using air as a removable barrier component. Superhydrophobic surfaces are often explored for applications where maintaining a permanent non-wetting surface is the critical design feature.[23-26] Such applications include surfaces which are anti-fouling, self-cleaning, and drag reducing, which, as these names highlight, are intended to have a permanently non-wetting surface for continued efficacy. We expanded on this design feature by using 3D superhydrophobic materials as opposed to a 2D superhydrophobic surface. Using the electrospinning technique leads to ‘stacked’ superhydrophobic surfaces, where wetting at the material surface does not displace air within the bulk material. This allows the entrapped air to be used as a component of the material. Our lab has a specific interest in drug delivery devices or depots for the treatment of established tumors and prevention of recurrent tumors after surgical resection, and therefore we are exploring 3D superhydrophobic meshes for this application.

As a first step towards applying the drug-loaded superhydrophobic electrospun meshes for preventing locoregional colorectal recurrence in vivo, this paper presents the following: 1) preparation of electrospun meshes, and demonstration of their favorable mechanical properties for reinforcement of the resection margin and bowel anastomosis with reapproximation around surgical staples; 2) the effect of loading the active chemotherapeutic metabolite SN-38 on distribution through electrospun fibers and resultant release profiles; 3) the release rates of the pro-drug CPT-11 compared to the metabolite SN-38 from electrospun PCL meshes with and without PGC-C18 doping, and with and without the use of air as a degradable barrier component for prolonged release; 4) the evaluation of the drug-loaded superhydrophobic meshes in an in vitro 90 day cytotoxicity assay with human colon carcinoma cells; and 5) the ability to observe the superhydrophobicity of the meshes using a clinical ultrasound instrument.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Materials

All solvents were purchased from Sigma without further purification. Stannous 2-ethylhexanoate, ε-caprolactone, stearic acid, N,N′-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide, and 4-(dimethylamino)pyridine were purchased from Sigma. Palladium on carbon was purchased from Strem Chemicals. Poly(ε-caprolactone) (70,000-90,000 MW) was purchased from Sigma. 7-ethyl-10-hydroxycamptothecin and Irinotecan Hydrochloride were purchased from Sigma. 5-benzyloxy-1,3-dioxan-2-one was prepared as previously reported. All reactions were performed under nitrogen atmosphere unless otherwise noted. NMR spectra were recorded on a Varian INOVA spectrometer (1H at 400 MHz). Chemical shifts were referenced to residual solvent peaks (CHCl3 peak at 7.24 ppm). DCM=dichloromethane, THF=tetrahydrofuran, DCC=N,N′-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide, DMAP=4-(dimethylamino) pyridine, CPT-11=Camptothecin-11 or Irinotecan Hydrochloride, SN-38=7-ethyl-10-hydroxycamptothecin, PCL= poly(ε-caprolactone), PGC-C18=poly(glycerol monostearate-co-ε-caprolactone), Pd/C=10% palladium on activated carbon, and PBS=phosphate buffered solution.

2.2 Synthesis of poly(glycerol monostearate-co-ε-caprolactone) (PGC-C18)

Poly(glycerol monostearate-co-ε-caprolactone), or PGC-C18, was prepared as reported previously.[27] Briefly, ε-caprolactone and 5-benzyloxy-1,3-dioxan-2-one monomers were mixed at a 4:1 molar ratio in a schlenk flask and subsequently evacuated and flushed with N2 three times. Sn(Oct)2 was used (M/I=500) to catalyze the ring-opening polymerization of the monomers at 140 °C for 18 h, and the resulting copolymer was isolated by precipitation in cold methanol (99% yield). The benzyl-protecting groups on the copolymer were removed via palladium-catalyzed hydrogenation overnight in THF, and filtered through Celite (95% yield). The deprotected polymer, stearic acid, DCC, and DMAP were dissolved in DCM and stirred at room temperature for 18 hours. DCU was filtered and the solvent evaporated. The product, PGC-C18, was dissolved in DCM and precipitated in cold methanol. The polymer was filtered and dried by evaporation (93% yield).

2.3 Size exclusion chromatography (SEC)

Molecular weight determinations were performed via size exclusion chromatography using THF as the eluent on a Polymer Laboratories PLgel 3 μm MIXED-E column (3 μm bead size) and a Rainin HPLC system (temp=25 °C; flow rate=1.0 mL/min). Polystyrene standards (Polysciences, Inc.) were used for calibration. PGC-C18 was shown to have a Mn=21,100 and a polydispersity of Mw/Mn=1.73.

2.4 Formation of doped and undoped poly(ε-caprolactone) meshes

All electrospinning solutions were 20 w/v% and prepared in a solvent mixture of 5:1 chloroform/methanol. Undoped PCL electrospinning solutions were prepared by dissolving PCL in chloroform and allowing full dissolution. This was followed by adding methanol with rigorous vortexing. Doped PCL electrospinning solutions were prepared in a similar fashion, where 2.5 – 10 w/w% of PCL was replaced with PGC-C18 to maintain a 20 wt/v% solution. Solutions were loaded into a glass syringe and placed into a syringe pump set at a flow rate of 10 mL/hr. A 12-18 kV high voltage lead was applied at the base of the syringe needle. A grounded rotating collector was covered in aluminum foil and placed 12 - 25 cm away from the needle. Meshes were run such that the total thickness was 300 μm. Drug loaded meshes were made in the same way, where SN-38 or CPT-11 was added to the electrospinning solution and allowed to completely dissolve.

2.5 Fiber morphology and characterization

Samples for scanning electron microscopy were prepared by mounting meshes on an aluminum sample stub and then sputter-coated with a 5 nm layer of gold–palladium alloy. Samples were then imaged on a Zeiss SUPRA 40VP field emission scanning electron microscope using an accelerating voltage of 2 kV. Fiber size analysis was performed using Image J, where all fibers in a representative SEM image were sized.

2.6 Apparent contact angle measurements

Apparent contact angle measurements of electrospun meshes were used as a measure of hydrophobicity/superhydrophobicity with each doping concentration of PGC-C18 (Kruss DSA100 Goniometer). Droplets were analyzed using Sessile drop fitting mode.

2.7 Confocal microscopy to determine drug distribution through fibers

Scanning confocal microscopy was performed to determine the distribution of SN-38 in undoped and doped electrospun meshes (Olympus Fluo-View 1000). XYZ acquisition was controlled using the FV10v1.8b software. Three dimensional Z-stacks of confocal slices were acquired using the FV10v1.8b software, with the sampling step set to half the axial resolution of the lens for ideal sampling. A 405 nm laser was used for excitation, and emission was recorded between 475-575 nm. 1%, 40%, and 80% laser power were used for 1, 0.1, and 0.01 wt% SN-38 respectively. Care was taken not to photobleach drug for accurate analysis during confocal imaging. Z-stack images were taken at 5 different regions for each drug concentration. Within each z-stack series, 5 different fibers were examined in ImageJ to determine a relative fluorescent intensity profile across the center of the fiber. Relative intensity was used as a measure of drug distribution within a single fiber, but could not be used as a measure between fibers within a sample or between samples.

2.8 Ultrasound to visualize air within electrospun meshes

Native and degassed electrospun meshes were visualized using a Vevo 770 imaging setup (VisualSonics, Inc, Toronto, Canada) with a 55 MHz scanhead and a 4 cm working distance. Native meshes were visualized with no prior treatment. Degassed PCL electrospun meshes received a 10 second sonication treatment using a 600W probe sonicator at 40% power. Degassed PCL electrospun meshes with 10% PGC-C18 received a 120 second sonication treatment using the same conditions, as the air layer was more robust in the more hydrophobic meshes. Both the mesh and scanhead were submerged in water during visualization.

2.9 Mechanical testing of electrospun meshes

Electrospun meshes were tested using ASTM standard D882 for testing thin plastic sheeting (Instron 5848 Micro-tester). Meshes were cut into 8 cm × 1 cm × 0.3 mm strips (lxwxh) from a larger electrospun sheet, and tested using a constant strain rate (ε= 0.05/s) to a maximum of ε= 1. The elastic modulus of each mesh was calculated using the linear region of the stress-strain curve (ε < 0.2), and the ultimate tensile strength was recorded.

2.10 Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) to measure drug dissolution

Thermal analysis of electrospun meshes to determine drug dissolution was performed using differential scanning calorimetry (Q100, TA Instruments). Meshes (3 mg) were hermetically sealed in an aluminum crucible with an empty crucible used as a reference. Samples were analyzed from 0-300 °C heated at a rate of 5 °C/min with a N2 flow rate of 20 mL/min.

2.11 Chemotherapeutic agents CPT-11 and SN-38

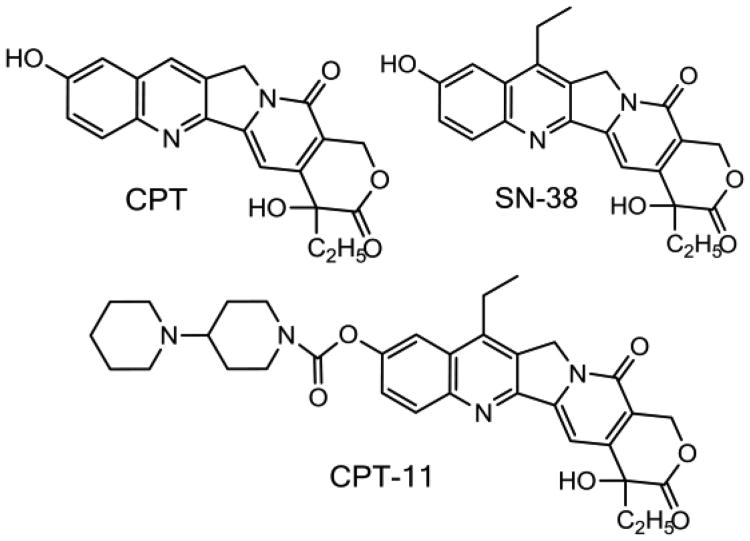

Camptothecin was first isolated by Wall [28] from the bark and leaves of the Camptotheca acuminata tree, and showed strong antitumor activity against L1210 leukemia (Fig. 1). However, the poor water solubility of camptothecin limited its early use to the soluble sodium salt form (the open lactone form), which showed minimal anticancer activity and several side effects such as diarrhea and hemorrhagic cystitis. Consequently, synthetic analogs and prodrugs have been explored and developed over the last thirty years, and, today, only two camptothecin agents have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA): irinotecan (Camptosar®) and topotecan (Hycamtin®). 7-Ethyl-10-hydroxy-camptothecin or SN-38 is the active metabolite of irinotecan (Fig. 1)

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of camptothecin (CPT), the pro-drug CPT-11, and its active metabolite SN-38. (Irinotecan, Camptosar).

Camptothecins have had their greatest utility in primary and metastatic colon carcinoma, platinum-refractory ovarian cancer, and small cell lung carcinoma. The antitumor activity of camptothecin results from inhibition of Topoisomerase-I, a nuclear enzyme, involved in chromatic organization, mitosis, and DNA replication, transcription and recombination.[29] Topoisomerase-I binds DNA and creates a transient break in one DNA strand while binding to the 3′-phosphoryl end of the broken DNA strand. The camptothecin binds to and stabilizes the DNA-topoisomerase I complex thus blocking DNA relegation with an accumulation of single-stranded DNA breaks. These processes are itself not toxic to the cell. However, the interaction of the DNA replication fork with this ternary drug-enzyme-DNA complex produces an irreversible double-strand break which results in controlled cell death (i.e., apoptosis). As expected, camptothecin is more potent to tumors with high topoisomerase-I levels. With regards to this application, topoisomerase-I concentration is increased in colon cancers by 30-fold compared to normal colonic mucosa, supporting the use of this drug for treatment of colon cancer.[30]

2.12 In vitro drug release, encapsulation efficiency, and lactone ring stability determined by HPLC

In vitro release, encapsulation efficiency, and the stability of the lactone ring for SN-38 and CPT-11 were determined using a HP 1090 192 HPLC system with a fluorescence detector, and a Phenomenex Prodigy 5 ODS reverse-phase column (150×4.6 mm, 5 μm). For SN-38 detection, the mobile phase was composed of 40% acetonitrile and 60% 0.075 M ammonium acetate buffer and delivered at 0.8 mL/min (λex=380 nm, λem=550 nm). Calibration curves were constructed for both lactone (rt=3.8 min) and carboxylate (rt=2.7 min) forms with sensitivities of 1 ng/mL. For CPT-11 detection, the mobile phase was composed of 60% acetonitrile and 40% 0.075 M ammonium acetate buffer and delivered at 1 mL/min (λex=380 nm, λem=460 nm). Calibration curves were constructed for both lactone (rt=3.3 min) and carboxylate (rt=2.2 min) forms with sensitivities of 1 ng/mL.

The release kinetics from SN-38 and CPT-11 (n=3) were assessed in PBS buffer at 37 °C. Each mesh was 10 mg (1×1×0.03cm) and loaded with 1%, 0.1% or 0.01% drug (wt. drug/wt. polymer). Release was done in 50 mL of PBS. At specific time points, an aliquot of release media was removed and the concentration of drug was measured using HPLC. The release medium was changed at regular intervals to maintain the pH and ensure sink conditions. Release studies were continued until all meshes stopped releasing. SN-38 loaded meshes for the ethanol dip study were dipped in ethanol for <1 second, and were immediately placed in PBS buffer. The remainder of the procedures remained constant. The HPLC retention time for the released SN38 or CPT11 was the same as native SN38 or CPT11 confirming that the drug had not been compromised by the fabrication process.

Encapsulation efficiency of SN-38 and CPT-11 within meshes was determined by dissolving meshes in dichloromethane, followed by the addition of a large quantity of water. Nitrogen was bubbled through the dichloromethane phase to completely remove it, which allowed precipitation of polymer, and the previously encapsulated drug to remain in the water phase. Concentration of the drug in water was measured using HPLC. Encapsulation of drug in electrospun meshes was quantitative.

The ratio of active lactone to inactive carboxylate of SN-38 was quantified by collecting aliquots of release media before significant conversion to the carboxylate form could occur. Meshes were kept in pH 7.4 PBS as their long term release media, and at different time points were transferred to fresh PBS (pH=6.4, adjusted with acetic acid) for 60 min at 37 °C, after which aliquots were removed and immediately analyzed. SN-38 converted from 100% lactone form to 73% lactone at pH=6.4 over 60 min for the control experiments. The stability study was performed until the amount of drug released became lower than the limit of detection.

2.13 Cell care and maintenance

HT-29 colorectal cancer cells were maintained in McCoy's Modified 5A Media containing 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. Cells were maintained in a humidified atmosphere at 37°C and 5% CO2. At designated time points for use in vitro cytotoxicity study, subconfluent cells were harvested and seeded on 12-well plates at 30,000 cells/well.

2.14 In vitro cytotoxicity study

Drug-loaded and unloaded electrospun meshes and mesh blends (with doped PGC-C18) were prepared with 1 wt%, 0.1 wt%, or 0.01 wt% SN-38, or 1 wt% CPT-11. Meshes were placed in permeable transwells (Polyester membrane insert, 3.0 μm pore size; Corning Incorporated, Corning, NY) and maintained in PBS at 37 °C. At day 5 in the released study, the transwells and meshes were transferred to wells containing tumor cells in 3 mL of fresh serum positive media. After 24 hours of incubation with tumor cells, transwells and meshes were removed and placed in fresh PBS at 37 °C as a continued sink in the absence of tumor cells. Five days after treatment with the respective mesh, tumor cell viability was tested using a colorimetric MTS (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium) cell proliferation assay (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Cell viability in each well was calculated as the percentage of the positive control absorbance. This procedure was repeated with the same mesh every 5 days in order to determine long term drug release and anti-proliferation effects of SN-38 and CPT-11 loaded electrospun meshes. Statistical significance between groups was tested using a two sample Student's T-test with unequal variances.

3. Results and Discussion

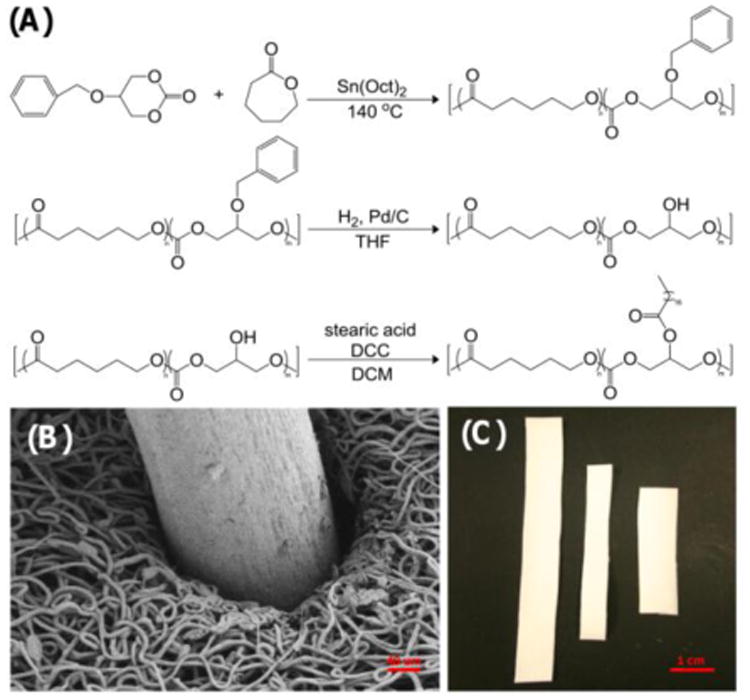

We are exploring electrospun superhydrophobic meshes as a promising new local delivery strategy for preventing locoregional colorectal cancer recurrence. The superhydrophobic meshes under investigation are electrospun poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL) doped with 10% poly(glycerol monostearate-co-ε-caprolactone) (PGC-C18) (Figure 2A). PGC-C18 was selected as the polymer dopant due to the relative ease in functionalizing the backbone with many pendant groups, including stearic acid [21, 27, 31], where the addition of 10% PGC-C18 produces the desired superhydrophobic effect due to a high apparent contact angle (143°) (Table 1). PCL was purchased, whereas PGC-C18 was synthesized as shown in Figure 2A.[21, 27, 31] Briefly, the carbonate monomer of glycerol, 5-benzyloxy-1,3-dioxan-2-one, was synthesized, after which ε-caprolactone and the carbonate monomer were copolymerized in a 4:1 ratio (21 kD). The benzyl group on the secondary hydroxyl of the carbonate monomer of the copolymer was subsequently removed, followed by the addition of stearic acid using a standard DCC coupling method.

Figure 2.

(A) Synthetic scheme used to produce the hydrophobic polymer dopant PGC-C18 from ε-caprolactone and the carbonate monomer of glycerol. (B) SEM image of a sample electrospun mesh reapproximating around a surgical staple. (C) Sample electrospun strips cut from a larger electrospun mesh which will provide mechanical reinforcement and deliver drug to the colon resection margin.

Table 1.

Electrospinning parameters selected for undoped PCL and 10% PGC-C18 doped PCL. Fiber sizes of electrospun meshes with 0% and 10% PGC-C18 doping were comparable. Doping 10% PGC-C18 into PCL electrospun meshes showed a significant increase in the apparent contact angle compared to undoped PCL electrospun meshes.

| PCL + 0% PGC-C18 | PCL + 10%PGC-C18 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Electrospinning conditions | Concentration | 20 wt/v% | 20 wt/v% |

| Solvent | 5:1 CHCl3 | 5:1 CHCl3 | |

| Flow rate | 25 mL/hr | 25 mL/hr | |

| Voltage | 15 kV | 12 kV | |

| Collector distance | 25 cm | 15 cm | |

| Characterization | Fiber size | 7.7 ± 1.2 μm | 7.2 ± 1.4 μm |

| Thickness | 300 μm | 300 μm | |

| Apparent CA | 121° | 143° | |

| SN-38conc. | 1%, 0.1%, 0.01% | 1%, 0.1% 0.01% | |

| CPT-11 conc. | 1% | 1% | |

The electrospinning parameters used for the superhydrophobic meshes were chosen to produce large, micron-sized fibers and are listed in Table 1. Previous work has shown that micron-sized fibers release drug more slowly than nano-sized fibers as a result of less water-polymer contact.[32] We therefore targeted larger fiber sizes to promote slow drug release over many weeks with the overall project goal of delivering chemotherapy to cancer cells throughout a large number of cell cycles to effectively prevent locoregional recurrence.

Many of the electrospinning parameters chosen were adapted from previously published procedures found in the literature.[33] The electrospinning parameters were kept constant for PCL and PCL with 10% PGC-C18, except that the working distance and applied voltage were tailored to the PGC-C18 concentration to account for a lower electrospinning solution viscosity and to allow an appropriate drying distance/time between needle and collector. Meshes were produced using a rotating, translating drum to ensure homogeneity with an overall mesh thickness of 300 microns. An important design feature of the superhydrophobic meshes for this application is pliability and mechanical strength, including both the ability to cover a deformable tissue, as well as maintain integrity on a tissue undergoing peristalsis or distension. A representative SEM image of an electrospun PCL mesh doped with 10% PGC-C18 shows that the mesh reapproximates around surgical staples, suggesting it may be able to buttress the staple line at the anastomosis (Fig. 2B). The mesh can be cut into strips from a large superhydrophobic electrospun mesh (10 × 12 cm) to produce custom shapes for treating a specific area (Fig. 2C).

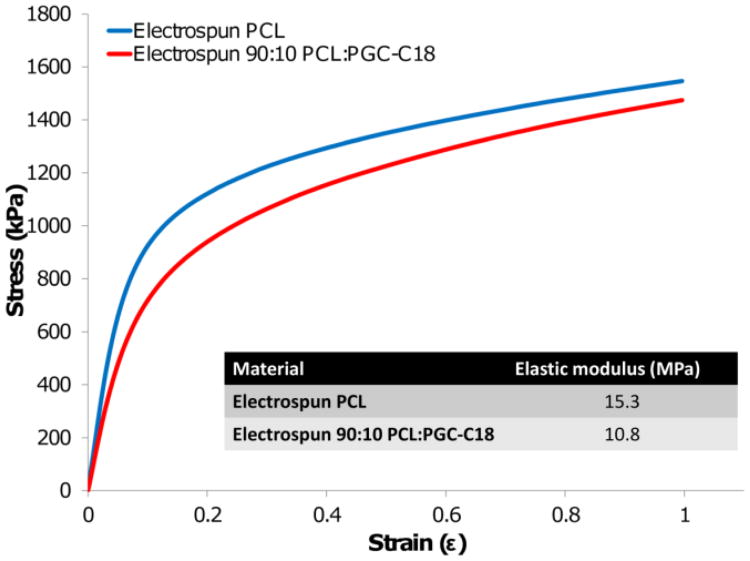

These electrospun meshes are flexible and deformable, making them ideal for fitting the contours of the pelvis, or for approximating the rectum or colonic flexures. Additionally, both PCL and PGC-C18 will not degrade significantly in 3 months, which will provide mechanical stability to the anastomosis during the 3-6 week healing phase.[21, 34] This was confirmed for these superhydrophobic electrospun meshes by demonstrating the absence of weight or structural changes after incubating meshes in PBS at 37 °C for three months. We assessed strength in the axial direction by performing mechanical testing on strips of electrospun mesh. PCL has an elastic modulus of 15.3 MPa, and with 10% PGC-C18 doping the modulus is 10.8 MPa. This ∼30 prodrug CPT-11 has been adopted clinically over the active metabolite SN-38 since the poor solubility of SN-38 (≈36 μg/mL in PBS)[39] prohibits delivery of the clinically relevant dose needed for effective cancer treatment. Unfortunately, delivery of the prodrug CPT-11 faces two additional complexities. First, only 2-8% of CPT-11 is metabolized to form the active drug SN-38 in vivo.[40-41] Given that SN-38 is approximately 1000× more cytotoxic than CPT-11, inefficient CPT-11 metabolism reduces anticancer efficacy.[42] Secondly, hydrolysis of the lactone ring on CPT-11 and SN-38 at physiologic pH inactivates the drug. The t1/2 of SN-38 hydrolysis in PBS is 20 minutes, with only 13% of the active lactone form remaining after 1 hour. This suggests that achieving therapeutic SN-38 drug levels require very high levels of the prodrug or a means to harbor SN-38 from rapid hydrolysis.[43] The common severe side effects of irinotecan therapy include life threatening diarrhea, myelosuppresion, and hemorrhagic cystitis. Avoiding these toxicities as well as inhibiting the lactone to carboxylate conversion are critical when delivering a clinically effective dose of CPT-11/SN-38.[44] Consequently, there decrease in elastic modulus may be a result of a change in porosity as a result of fiber size decrease, or addition of a lower molecular weight polymer with fewer chain entanglements. The ultimate tensile strengths (UTS) of both mesh types is ≈1.5 MPa (p-value = 0.03), and compares well to other products proposed or evaluated for reinforcement after gastrointestinal surgery such as SEAMGUARD (UTS = 4 MPa) with the goal of preventing such anastomotic complications as leakage and dehiscence.[35]

With regards to drug delivery, CPT-11 and SN-38 were loaded into the superhydrophobic electrospun meshes. CPT-11 or Irinotecan HCl is a first line drug treatment in colorectal cancer[36], and is a prodrug, where the solublizing piperidinopiperidine group is cleaved by carboxyl esterases to form the potent topoisomerase I inhibitor SN-38.[37-38] The is significant opportunity to improve the delivery of irinotecan and other campothecins through various strategies including localized or targeted delivery.[37]

SN-38 and CPT-11 were embedded within electrospun meshes using the same electrospinning parameters for unloaded fiber meshes. To form the drug-electrospinning solution, drug was first added to chloroform and sonicated for an hour to form a colloid, after which polymer was added to the solution. The solution appeared cloudy prior to polymer addition, and turned clear after full dissolution of the polymer. Finally, methanol was added and the solution was vortexed thoroughly. The encapsulation efficiency of SN-38 and CPT-11 within meshes was quantitative (99%). Complete dissolution of SN-38 and CPT-11 within electrospun meshes was shown using DSC, where the absence of a melting peak for both drugs showed that drug had not aggregated, and was instead dispersed as individual molecules within the polymer meshes (data not shown).

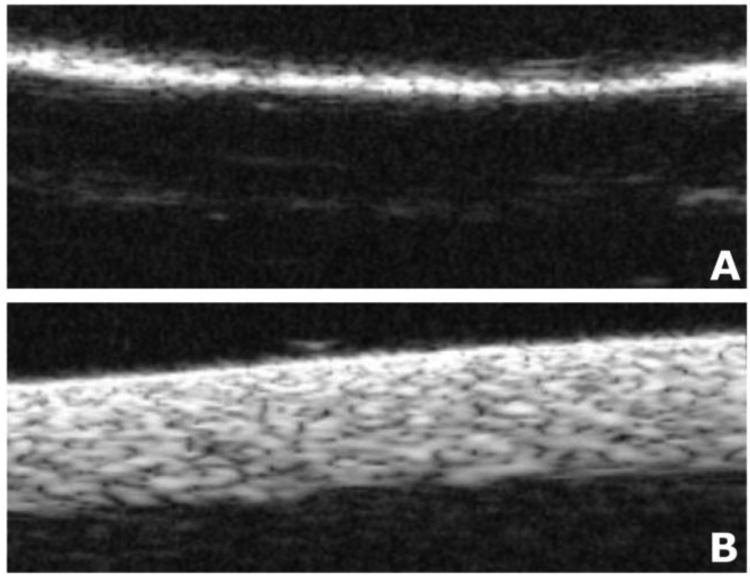

Next, we determined whether clinical ultrasound could be used to visualize the electrospun meshes, as well as to confirm their superhydrophobic character. Native meshes should reflect ultrasound at the mesh surface due to the large impedance gradient between the entrapped air and the mesh polymer. The air-polymer interface at the mesh surface will be bright and the bulk of the mesh appears dark (i.e. anechoic) with reflection of the acoustic signal at the air-polymer interface. We hypothesized that when superhydrophobic meshes are wetted (i.e., degassed), there will be decreased impedance gradient at the surface liquid-polymer interface, thus reducing reflectance at the surface and allowing detection of impedance differences at the liquid-polymer interfaces throughout the mesh. This results in observable changes in echogenicity, where the wetted high surface area polymer interface, with the absence of air, should afford an echogenic (white) signal for visualization of the mesh. Thus, ultrasound imaging would correlate and be predictive of the superhydrophobic or nonsuperhydrophobic state of the electrospun meshes.[45]

To test this hypothesis, a VisualSonics, Inc ultrasound imaging device with a 55 MHz scanhead was used to image both native and degassed electrospun meshes. Native electrospun meshes showed no water penetration after 2 hours and, as expected, the entrapped air results in an anechoic shadow within the bulk of the mesh appearing dark on ultrasound imaging with a bright edge (Fig. 4). This is in marked contrast to degassed electrospun meshes, where water now infiltrates the entire electrospun mesh structure, lowers the degree of ultrasound reflection and allows the entirety of the mesh to be visualized as an echogenic mesh. This further confirms that entrapped air is present in our superhydrophobic meshes and can serve as a degradable component within our materials to slow drug release.

Figure 4.

Representative ultrasound imaging of superhydrophobic electrospun meshes. (A) Image of native electrospun mesh shows a bright hyperechoic surface due to reflectance at the material surface; the rest of the electrospun mesh is dark. (B) Image of degassed electrospun mesh shows full-thickness of electrospun mesh with no air present. Meshes in this study are 300 μm thick.

This ability to visualize the mesh “remotely” with ultrasound will enable noninvasive monitoring of not just drug release correlating with the “wetting of the mesh”, but also serve as a marker for the surgical site after implantation. Ultrasound has been used successfully to image drug delivery systems and biomaterials such as electrospun scaffolds.[46-47] For example, the mesh will demarcate the area of the anastomosis to quickly identify surgical complications (i.e., anastomotic stricture or fluid collection) via transabdominal ultrasound. Currently, normal bowel gas can make the stapled anastomosis difficult to visualize and oral contrast with radiographic imaging via CT scanning is often required to rule out anastomotic complications, resulting in increased costs and radiation exposure for the patient. Occasionally a rectal ultrasound may be used to look for peri-anastomic fluid, but the need for a distending balloon within the rectum at the area of the anastomosis for good image quality is of significant concern in the clinical setting of a recent anastomosis. In addition to identifying surgical complications, the presence of the mesh at the anastomosis will also identify the area at greatest risk for recurrent disease and allow focused post-surgical surveillance of this area.

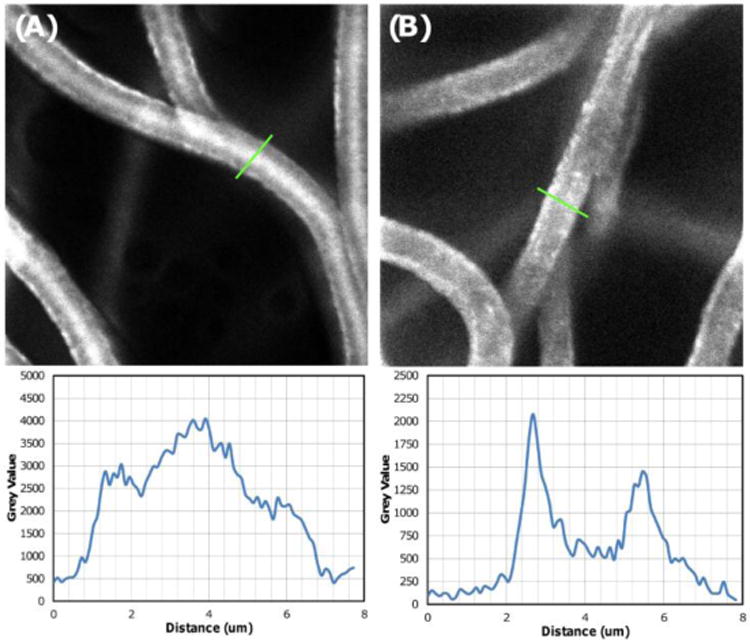

There is a precedent in the literature to suggest that changing drugs and drug loading concentrations in electrospun systems lead to variations in drug distribution within individual fibers.[48] Therefore, SN-38 was loaded into electrospun meshes at three different concentrations: 1, 0.1, and 0.01 wt%. To characterize drug partitioning within the polymeric system, electrospun fibers for all SN-38 concentrations were examined using confocal microscopy as the drug is fluorescent (Fig. 5). Results show a high concentration of drug partitioning into the center of the fibers for 1 wt% loaded electrospun fibers. Decreasing the drug concentration to 0.1 wt% drug showed the opposite effect, where very little drug is concentrated in the center of the fibers with a higher drug concentration partitioned to the surface. Further decreasing the drug concentration to 0.01 wt% (data not shown) seemed to show further surface partitioning, but photobleaching of SN-38 at this concentration complicated analysis due to the laser intensity required to collect sufficient signal. This effect of surface partitioning was the same for both PCL and PCL doped with PGC-C18, suggesting the variations in drug distribution within the fibers is related to the electrospinning process as opposed to polymer hydrophobicity.

Figure 5.

Confocal image of SN-38 distribution within electrospun meshes containing different % drug loading. SN-38 is fluorescent, and thus visible, and is seen as white on these confocal images (using a 60× water immersion lense). Both (A) 1 wt% and (B) 0.1 wt% SN-38 loaded meshes showed SN-38 partitioned to fiber surfaces, with 1 wt% SN-38 loaded meshes forming a drug reservoir within the core of the fibers and 0.1 wt% demonstrating greater surface segregation. This trend of surface and core segregation was observed for both undoped PCL and 10% PGC-C18 doped PCL.

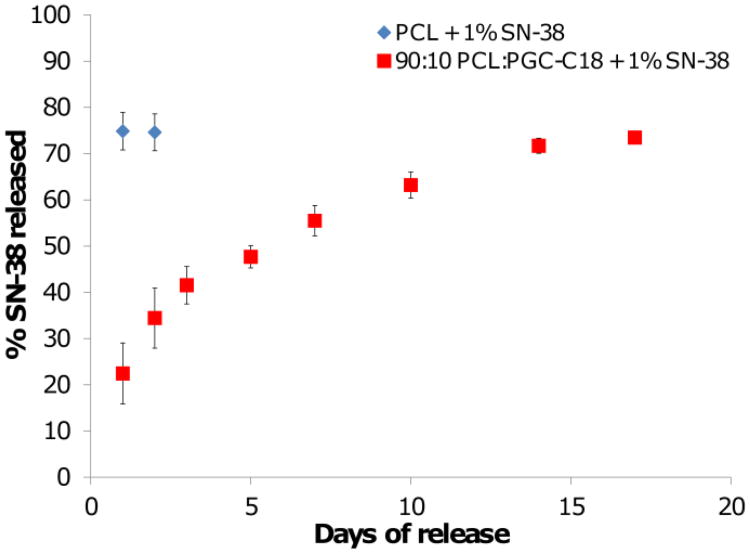

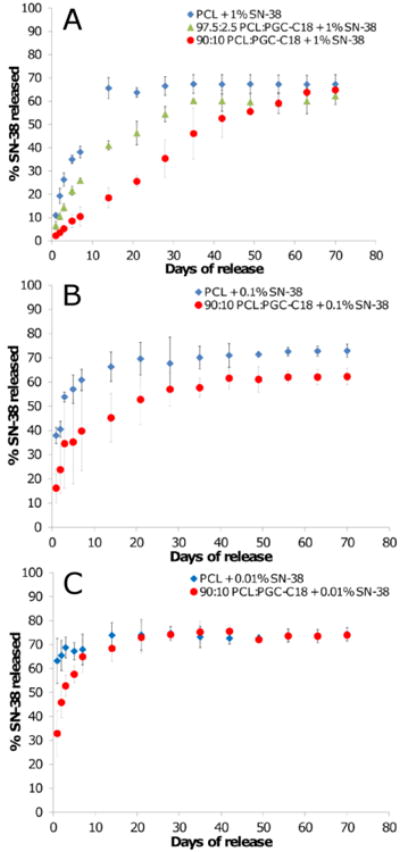

PCL electrospun meshes have an apparent contact angle of 121°, and doping 10% PGC-C18 increases the apparent contact angle to 143° (Table 1), indicating slower drug release should occur from meshes with 10% of PGC-C18 doping. Release data for different concentrations of SN-38 shows this to be the case with dramatically different release profiles for PCL meshes and PCL meshes doped with 10% PGC-C18 (Figure 6). SN-38 release is significantly slower for all three drug concentrations when doping 10% PGC-C18 into PCL meshes. Using 1 wt% SN-38 loading as an example for this phenomenon, we have previously shown that undoped PCL meshes quickly release their drug payload by 14 days whereas SN-38 is linearly released for 70 days without any significant burst release when doping PCL meshes with 10% PGC-C18.[1] To further show that drug release can be tailored via PGC-C18 doping, an additional mesh was run with 2.5% PGC-C18 doping with 1 wt% SN-38 loading (apparent CA = 128°). Doping with 2.5% PGC-C18 showed an intermediate release rate between PCL and 10% PGC-C18 doping, with extension of SN-38 release for an additional 10 days compared to PCL alone. PCL meshes doped with 30% and 50% PGC-C18 significantly slowed release compared to 10% PGC-C18 doping, with <10% SN-38 release at 9 weeks.[1] Decreasing the amount of drug loading to 0.1 wt% and 0.01 wt% increases both the release rate and burst release for PCL and PCL doped with 10% PGC-C18. The difference in SN-38 partitioning seen with confocal microscopy is consistent with this change in release. Loading with 0.1 wt% and 0.01 wt% SN-38 leads to surface segregation within individual electrospun fibers, leading to a smaller distance for drug to diffuse into the release media from fibers, thus accelerating drug release.

Figure 6.

SN-38 release profiles from electrospun meshes with (A) high (1 wt%), (B) medium (0.1 wt%), and (C) low drug loadings (0.01 wt%). Increasing the percent of PGC-C18 doping into PCL electrospun meshes decreased the release rate of SN-38. Decreasing the drug concentration in electrospun meshes increased the release rate of SN-38. Release curves for 1 wt% SN-38 loaded PCL and 10% PGC-C18 doped PCL were previously reported.[1] (n=3).

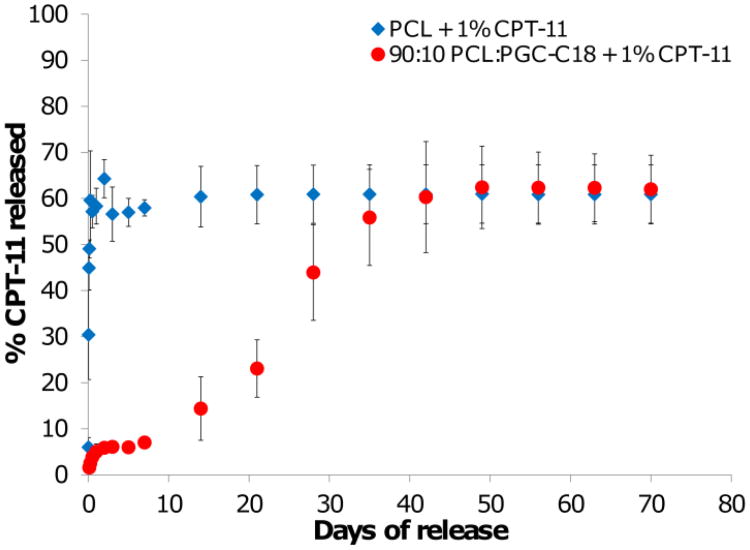

Similarly, release of 1 wt% CPT-11 loaded meshes was significantly delayed from PCL meshes doped with 10% PGC-C18 (Figure 7). Undoped PCL meshes release CPT-11 very quickly over a few days, whereas the addition of 10% PGC-C18 slows CPT-11 release dramatically, with an initial burst release of ≈5% and a gradual release of drug out to 50 days. The release profile seen with 10% of PGC-C18 suggests that CPT-11 localized at the surface of the meshes is released very quickly, accounting for the burst, and is followed by slow, sustained release as water infiltrates into the meshes. CPT-11 from both PCL and PCL doped with 10% PGC-C18 is released more quickly than equitable meshes loaded with SN-38 due to the increased solubility of CPT-11 in the release media. This finding makes intuitive sense since the prodrug CPT-11 was selected for systemic delivery due to its increase solubility over SN-38. Release with all drug/dose/polymer formulations reached a maximum of ≈72% of total encapsulated drug. The remaining drug which was not released was shown to still be encapsulated in meshes as confirmed by HPLC. This is a common phenomenon with surface eroding polymers such as PCL, where a percentage of the drug is trapped within the polymer matrix until bulk matrix degradation occurs.

Figure 7.

CPT-11 release profiles from electrospun meshes with 1 wt% CPT-11. Increasing the amount of PGC-C18 doping in PCL electrospun meshes decreased the rate of CPT-11 release. (n=3)

We performed an additional release study with 1 wt% SN-38 loaded electrospun meshes to determine how drug release rates change when air is removed and no longer controls drug release. Meshes were quickly dipped in ethanol and moved to PBS release buffer. Ethanol has a low surface tension (22.4 mN/m) and wets all superhydrophobic electrospun meshes regardless of PGC-C18 doping. Without the air entrapped within electrospun meshes, a significantly different release profile is observed. PCL meshes release all of the drug payload within 1 day compared to 14 days from native electrospun meshes where air is still entrapped (Fig. 8 vs. Fig 6A). PCL meshes with 10% PGC-C18 doping release all drug within 17 days rather than 70 days. A large burst of SN-38 is released in both mesh types, where the large concentration of surface drug seen with confocal imaging quickly partitions into solution. With slow penetration of water into native electrospun meshes, and the displacement of entrapped air, the release of surface drug is normally averaged out over many days. However, with ethanol wetting, the mesh is degassed and all surface drug is released as a bolus within 2 days. With 10% PGC-C18 doping, linear drug release from electrospun fibers is seen for 10 days after the initial burst. Overall, this study reconfirms the effectiveness of PGC-C18 to slow the release of a hydrophobic drug, as well as the importance of air in slowing the release from the superhydrophobic meshes.

Figure 8.

Release of 1 wt% SN38 from electrospun meshes, with and without 10% PGC-C18 doping, which have been forced to wet with an ethanol dip treatment. PCL meshes and PCL meshes with 10% PGC-C18 release much more quickly than their native control noted in Figure 6A. (n=4)

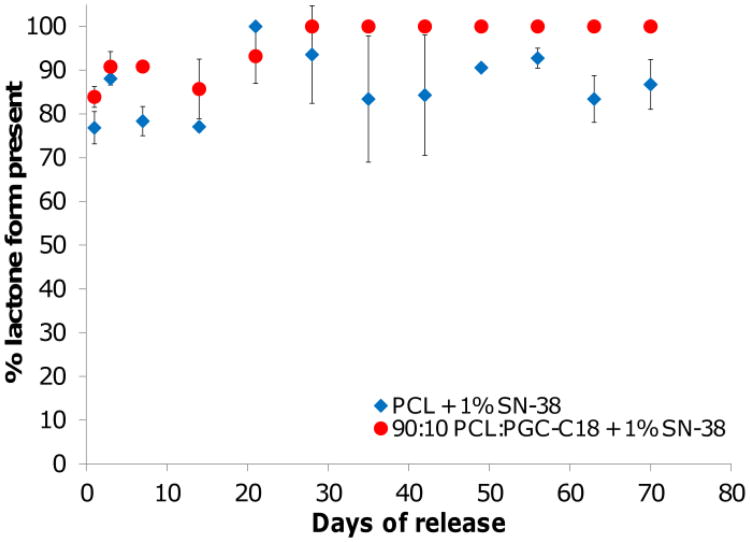

Another potential benefit of superhydrophobic electrospun meshes is a means to protect the active form of SN-38 and CPT-11 from hydrolysis, thereby keeping the lactone ring intact and the drug active. We performed an additional release study to determine if the active form of SN-38 was preserved within electrospun meshes. Figure 9 shows that the lactone form is protected until released into PBS in both PCL and PCL doped with PGC-C18, with greater than 75% of SN-38 sampled from the release media being present in the lactone form. This is compared to 73% of SN-38 remaining in the active lactone form in the control experiments, where a bolus of SN-38 was added to pH 6.4 PBS for an hour.

Figure 9.

Percent of SN-38 released in lactone form from 1 wt% loaded PCL and PCL doped with 10% PGC-C18. Both meshes protect SN-38 from ring opening to the carboxylate form compared to equilibrium values. (n=3)

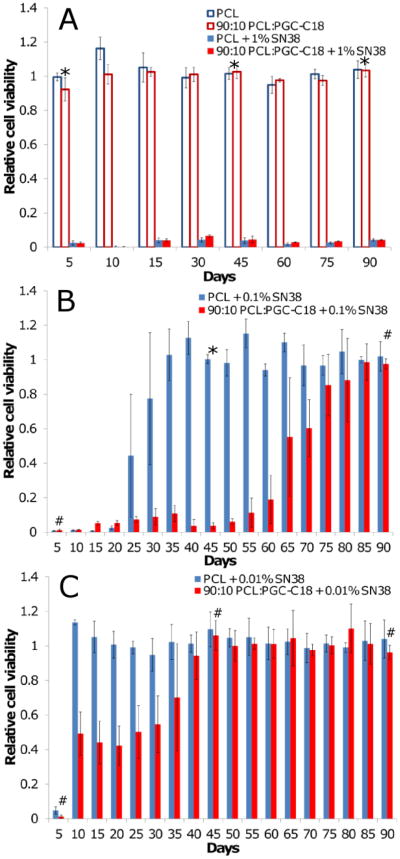

Next superhydrophobic meshes were assessed in an in vitro cytotoxicity study against a colorectal cancer cell line (HT-29). Studies were performed by exposing cancer cells grown in monolayer cultures to meshes for a total of 24-hours while in serum. Meshes were subsequently removed and tumor cell viability was tested using a standard MTS assay 5 days later. Meshes were incubated in PBS between each time point with PBS replaced daily to ensure sink conditions for continued drug release and then moved to a new HT-29 cell monolayer for another 24 hour incubation period. Figure 10 shows the amount of SN-38 released from either PCL or PCL doped with 10% PGC-C18 loaded with 1 wt% SN-38 is sufficient to be cytotoxic to HT-29 for at least 90 days, whereas neither mesh was toxic without SN-38 loading. The continued cytotoxicity of PCL meshes, despite the limited duration of detected SN38 release (20 days from PCL meshes; 70 days from PCL doped with 10% PGC-C18 meshes), is likely due to the extremely low IC50 of SN-38 (3.4 ng/mL for HT-29 cells).[49] This is supported by the very small amounts of SN-38 released over 70 days (>10 ng/day release at each time point) and detected in the lactone-carboxylate conversion study from both types of meshes when the initial SN38 load was high. Given that the 1 wt% SN38 loaded meshes were cytotoxic at all time points, we next investigated lower loadings of SN38 in order to study the dependency of mesh performance on drug loading. Decreasing this SN-38 dose by 10-fold to 0.1% loading, or 100-fold to 0.01% loading, further supports this hypothesis with drug release falling off more rapidly and resulting in a more marked difference between PCL and PCL with 10% PGC-C18. The resultant cytotoxicity profile more closely mimicked the in vitro release profile of the respective formulations with 0.1 wt% SN-38 loaded PCL meshes no longer killing cancer cells by day 30, and SN-38 loaded 10% PGC-C18 doped PCL meshes demonstrated extended tumor cell cytotoxicity through day 60. With 0.01 wt% loading, tumor cell cytotoxicity was observed for only 5 days with PCL meshes, whereas 10% PGC-C18 doped meshes showed low levels of killing out to 35 days.

Figure 10.

HT-29 viability with exposure to electrospun PCL and 10% PGC-C18 doped PCL meshes at three different SN-38 concentrations: (A) 1 wt%, (B) 0.1 wt%, and (C) 0.01 wt%. Unloaded mesh controls were not cytotoxic to cells. No difference in long term cytotoxicity was seen between PCL and 10% PGC-C18 doped PCL with 1 wt% SN-38. Decreasing the SN-38 loading to 0.1 wt% and 0.01 wt% showed superior long term in vitro cytotoxicity with 10% PGC-C18 doped PCL. A Student's t-test was performed at an early, mid, and late timepoint in the assay. An * above a time point signifies p<0.001, whereas a # indicates p>0.01 and is not statistically significant. (n=4)

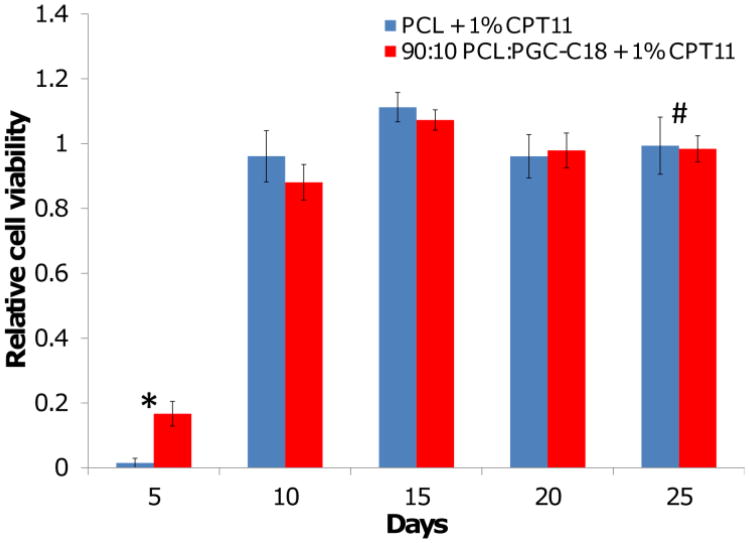

Given the low conversion of CPT-11 to SN-38 and the relatively rapid release, we hypothesized that meshes loaded with 1 wt% CPT-11 would be less effective at killing tumor cells over a long period of time. Similar to the 0.01% SN-38 loaded meshes, in vitro tumor cytotoxicity for either CPT-11 loaded PCL or 10% PGC-C18 doped meshes was observed for only 5 days (Fig. 11). The viability trend for both PCL and PCL doped with 10% PGC-C18 is the same, and highlights that a much larger dose of CPT-11 is required to treat cancer cells when compared to SN-38 (Figure 10A). This finding demonstrates that delivery of the more potent active drug SN-38 from the superhydrophobic electrospun meshes is an attractive alternative to delivering the prodrug CPT-11 systemically or using a local drug delivery platform.

Figure 11.

HT-29 viability with exposure to 1% CPT-11 loaded PCL and 10% PGC-C18 doped PCL meshes. No difference was seen between PCL and 10% PGC-C18 doped PCL meshes. CPT-11 loaded meshes showed poor long term cancer cell treatment. An * above a time point signifies p<0.001, whereas a # indicates p>0.01 and is not statistically significant. (n=4)

We have presented data demonstrating that the displacement of air is a viable method for controlling drug release; yet, there are a number of additional experiments which must be completed before this idea is fully vetted. First and foremost, animal studies must be conducted as in vivo efficacy and safety studies are key steps for the thorough evaluation of these materials to show clinical relevance. Second, superhydrophobic meshes must show efficacy in ex vivo tissue stapling studies as reinforcement devices, with a reduction in common resection complications such as leakage. And finally, further investigation of superhydrophobic mesh performance in more robust in vitro environments containing biologic surfactants are necessary, as the presence of surfactants may shift the longevity of the entrapped air layer. This is supported by the cell studies performed in serum, which show the meshes to be efficacious.

Local delivery of chemotherapeutic agents via an implanted biomaterial is beneficial when: 1) systemic treatment approaches are ineffective or highly toxic; 2) prolonged therapeutic levels of chemotherapy are not achievable due to poor aqueous solubility, non-ideal pharmacokinetics, or biodistribution; or 3) the incidence of local recurrence does not warrant universal treatment of all patients with a highly morbid systemic therapy. The Gliadel Wafer is the only commercially available product designated for the prevention of local tumor recurrence, which is approved exclusively for use in high-grade malignant glioma in the brain.[50] The rigid wafers release the anti-cancer drug Carmustine over several days as the polymer degrades within three weeks. Several design features of the Gliadel Wafer, including its rigidness, rapid drug release, and the anti-cancer drug chosen for incorporation, make it unacceptable for most other applications. Consequently, there is an opportunity for development of local delivery platforms that can inhibit or prevent recurrent tumor growth in other types of malignancies, including colorectal cancer, or cancers in other anatomic locations outside of the brain. Superhydrophobic meshes can be used to tailor the release rate of a first line cancer treatment for colorectal cancer (CPT-11), as well as its highly potent metabolite (SN-38), using different PGC-C18 doping concentrations and drug loading. SN-38 loaded superhydrophobic meshes showed efficacy in treating cancer cells in an in vitro cytotoxicity model, while CPT-11 loaded meshes were ineffective at the same concentration, thereby suggesting we can deliver the active drug directly to the target site without the need for metabolic conversion. These meshes are mechanically robust and flexible, making them potentially easy to incorporate into current surgical procedures/devices during colorectal surgery, with the added ability to observe them and the status of their drug delivery using clinical ultrasound. Overall, we demonstrate that these superhydrophic electrospun meshes pose a novel mechanism of local drug delivery and are worthy of further evaluation as a means to potentially prevent locoregional recurrence following surgical resection of tumor due to their mechanical properties, ability to noninvasively monitor and to tailor drug release of an otherwise insoluble yet highly effective active agent (SN-38), and effectiveness when tested in a long-term in vitro cytotoxicity assay against human colorectal tumor cells.

Figure 3.

Mechanical performance of PCL and PCL doped with 10% PGC-C18 under constant strain rate. The elastic moduli of electrospun PCL and PCL doped with PGC-C18 are 15.3 and 10.8 MPa, respectively. The ultimate tensile strength of PCL meshes is approximately 1.5 MPa. (n=3)

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by BU, BU Training Grant in Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, BU MSE Innovation Grant, BU Nanotheranostics ARCBWH, CIMIT, Coulter Foundation, ARRC Ultrasound Micro-Imaging Core at BUSM, NIH R25 CA153955, and NIH R01CA149561.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Yohe ST, Colson YL, Grinstaff MW. Superhydrophobic Materials for Tunable Drug Release: Using Displacement of Air to Control Delivery Rates. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2012;134:2016–2019. doi: 10.1021/ja211148a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, Ward E. Cancer statistics, 2010, CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2010;60:277–300. doi: 10.3322/caac.20073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benson Al B, 3rd, Schrag D, Somerfield Mark R, Cohen Alfred M, Figueredo Alvaro T, Flynn Patrick J, Krzyzanowska Monika K, Maroun J, McAllister P, Van Cutsem E, Brouwers M, Charette M, Haller Daniel G. American Society of Clinical Oncology recommendations on adjuvant chemotherapy for stage II colon cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2004;22:3408–3419. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.05.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sjovall A, Granath F, Cedermark B, Glimelius B, Holm T. Loco-regional recurrence from colon cancer: a population-based study. Annals of Surgical Oncology. 2007;14:432–440. doi: 10.1245/s10434-006-9243-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Balch Glen C, De Meo A, Guillem Jose G. Modern management of rectal cancer: a 2006 update. World Journal of Gastroenterology : WJG. 2006;12:3186–3195. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i20.3186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Consten Esther CJ, Gagner M, Pomp A, Inabnet William B. Decreased bleeding after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy with or without duodenal switch for morbid obesity using a stapled buttressed absorbable polymer membrane. Obesity Surgery. 2004;14:1360–1366. doi: 10.1381/0960892042583905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Langer R. Polymeric Delivery Systems for Controlled Drug Release. Chemical Engineering Communications. 1980;6:1–48. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weinberg BD, Blanco E, Gao J. Polymer implants for intratumoral drug delivery and cancer therapy. J Pharm Sci. 2008;97:1681–1702. doi: 10.1002/jps.21038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim S, Kim JH, Jeon O, Kwon IC, Park K. Engineered polymers for advanced drug delivery. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2009;71:420–430. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2008.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoffman AS. The origins and evolution of “controlled” drug delivery systems. J Control Release. 2008;132:153–163. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2008.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Exner AA, Saidel GM. Drug-eluting polymer implants in cancer therapy. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2008;5:775–788. doi: 10.1517/17425247.5.7.775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Souza R, Zahedi P, Allen CJ, Piquette-Miller M. Polymeric drug delivery systems for localized cancer chemotherapy. Drug Deliv. 17:365–375. doi: 10.3109/10717541003762854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moses MA, Brem H, Langer R. Advancing the field of drug delivery: taking aim at cancer. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:337–341. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00276-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davis ME, Chen Z, Shin DM. Nanoparticle therapeutics: an emerging treatment modality for cancer. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 2008;7:771–782. doi: 10.1038/nrd2614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Torchilin VP. Multifunctional nanocarriers. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2006;58:1532–1555. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2006.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee CC, MacKay JA, Frechet JMJ, Szoka FC. Designing dendrimers for biological applications. Nature Biotechnology. 2005;23:1517–1526. doi: 10.1038/nbt1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Colson YL, Grinstaff MW. Biologically Responsive Polymeric Nanoparticles for Drug Delivery. Advanced Materials. 2012 doi: 10.1002/adma.201200420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Souza R, Zahedi P, Allen CJ, Piquette-Miller M. Polymeric drug delivery systems for localized cancer chemotherapy. Drug Delivery. 2010;17:365–375. doi: 10.3109/10717541003762854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wolinsky JB, Colson YL, Grinstaff MW. Local drug delivery strategies for cancer treatment: Gels, nanoparticles, polymeric films, rods, and wafers. Journal of Controlled Release. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.11.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu R, Wolinsky JB, Walpole J, Southard E, Chirieac LR, Grinstaff MW, Colson YL. Prevention of Local Tumor Recurrence Following Surgery Using Low-Dose Chemotherapeutic Polymer Films. Annals of Surgical Oncology. 2010;17:184–191. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0856-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wolinsky JB, Liu R, Walpole J, Chirieac LR, Colson YL, Grinstaff MW. Prevention of in vivo lung tumor growth by prolonged local delivery of hydroxycamptothecin using poly(ester-carbonate)-collagen composites. Journal of Controlled Release. 2010;144:280–287. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu R, Wolinsky Jesse B, Catalano Paul J, Chirieac Lucian R, Wagner Andrew J, Grinstaff Mark W, Colson Yolonda L, Raut Chandrajit P. Paclitaxel-eluting polymer film reduces locoregional recurrence and improves survival in a recurrent sarcoma model: a novel investigational therapy. Annals of surgical oncology. 2012;19:199–206. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-1871-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Genzer J, Efimenko K. Recent developments in superhydrophobic surfaces and their relevance to marine fouling: a review. Biofouling. 2006;22:339–360. doi: 10.1080/08927010600980223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakajima A, Hashimoto K, Watanabe T. Recent studies on super-hydrophobic films. Monatsh Chem. 2001;132:31–41. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li XM, Reinhoudt D, Crego-Calama M. What do we need for a superhydrophobic surface? A review on the recent progress in the preparation of superhydrophobic surfaces. Chem Soc Rev. 2007;36:1350–1368. doi: 10.1039/b602486f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nosonovsky M, Bhushan B. Superhydrophobic surfaces and emerging applications: Nonadhesion, energy, green engineering. Current Opinion in Colloid & Interface Science. 2009;14:270–280. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wolinsky JB, Ray WC, III, Colson YL, Grinstaff MW. Poly(carbonate-ester)s based on units of 6-hydroxyhexanoic acid and glycerol. Macromolecules. 2007;40:7065–7068. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wall ME, Wani MC, Cook CE, Palmer KH, McPhail AT, Sim GA. Plant antitumor agents. I. Isolation and structure of camtothecin, a novel alkaloidal leukemia and tumor inhibitor from Camptotheca acuminata. J Am Chem Soc. 1966;88:3888–3890. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hsiang YH, Hertzberg R, Hecht S, Liu LF. Camptothecin induces protein-linked DNA breaks via mammalian DNA topoisomerase I. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1985;260:14873–14878. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Giovanella BC, Stehlin JS, Wall ME, Wani MC, Nicholas W, Liu LF, Silber R, Potmesil M. DNA topoisomerase I-targeted chemotherapy of human colon cancer in xenografts. Science. 1989;246:1046–1048. doi: 10.1126/science.2555920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wolinsky JB, Yohe ST, Colson YL, Grinstaff MW. Functionalized Hydrophobic Poly(Glycerol-co-ε-Caprolactone) Depots for Controlled Drug Release. Biomacromolecules. 2012;13:406–411. doi: 10.1021/bm201443m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xie J, Wang CH. Electrospun Micro- and Nanofibers for Sustained Delivery of Paclitaxel to Treat C6 Glioma in Vitro. Pharmaceutical Research. 2006;23:1817–1826. doi: 10.1007/s11095-006-9036-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pham QP, Sharma U, Mikos AG. Electrospun Poly(ε-caprolactone) Microfiber and Multilayer Nanofiber/Microfiber Scaffolds: Characterization of Scaffolds and Measurement of Cellular Infiltration. Biomacromolecules. 2006;7:2796–2805. doi: 10.1021/bm060680j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scappaticci FA, Fehrenbacher L, Cartwright T, Hainsworth JD, Heim W, Berlin J, Kabbinavar F, Novotny W, Sarkar S, Hurwitz H. Surgical wound healing complications in metastatic colorectal cancer patients treated with Bevacizumab. J Surg Oncol. 2005;91:173–180. doi: 10.1002/jso.20301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kuzu MA, Koksoy C, Kale T, Demirpence E, Renda N. Experimental study of the effect of preoperative 5-fluorouracil on the integrity of colonic anastomoses. The British Journal of Surgery. 1998;85:236–239. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1998.02876.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li QY, Zu YG, Shi RZ, Yao LP. Review camptothecin: current perspectives. Curr Med Chem. 2006;13:2021–2039. doi: 10.2174/092986706777585004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mathijssen RHJ, Van Alphen RJ, Verweij J, Loos WJ, Nooter K, Stoter G, Sparreboom A. Clinical pharmacokinetics and metabolism of irinotecan (CPT-11) Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:2182–2194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pizzolato JF, Saltz LB. The camptothecins. Lancet. 2003;361:2235–2242. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13780-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang JA, Xuan T, Parmar M, Ma L, Ugwu S, Ali S, Ahmad I. Development and characterization of a novel liposome-based formulation of SN-38. International Journal of Pharmaceutics. 2004;270:93–107. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2003.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rothenberg ML, Kuhn JG, Burris HA, 3rd, Nelson J, Eckardt JR, Tristan-Morales M, Hilsenbeck SG, Weiss GR, Smith LS, Rodriguez GI, et al. Phase I and pharmacokinetic trial of weekly CPT-11. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 1993;11:2194–2204. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.11.2194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rothenberg ML, Kuhn JG, Schaaf LJ, Rodriguez GI, Eckhardt SG, Villalona-Calero MA, Rinaldi DA, Hammond LA, Hodges S, Sharma A, Elfring GL, Petit RG, Locker PK, Miller LL, von Hoff DD. Phase I dose-finding and pharmacokinetic trial of irinotecan (CPT-11) administered every two weeks. Annals of Oncology. 2001;12:1631–1641. doi: 10.1023/a:1013157727506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kawato Y, Aonuma M, Hirota Y, Kuga H, Sato K. Intracellular roles of SN-38, a metabolite of the camptothecin derivative CPT-11, in the antitumor effect of CPT-11. Cancer Research. 1991;51:4187–4191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Burke TG, Mi Z. Ethyl substitution at the 7 position extends the half-life of 10-hydroxycamptothecin in the presence of human serum albumin. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 1993;36:2580–2582. doi: 10.1021/jm00069a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Erickson-Miller CL, May RD, Tomaszewski J, Osborn B, Murphy MJ, Page JG, Parchment RE. Differential toxicity of camptothecin, topotecan, and 9-aminocamptothecin to human, canine, and murine myeloid progenitors (CFU-GM) in vitro. Cancer Chemotherapy and Pharmacology. 1997;39:467–472. doi: 10.1007/s002800050600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jambrik Z, Monti S, Coppola V, Agricola E, Mottola G, Miniati M, Picano E. Usefulness of ultrasound lung comets as a nonradiologic sign of extravascular lung water. The American journal of cardiology. 2004;93:1265–1270. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tillman BW, Yazdani SK, Lee SJ, Geary RL, Atala A, Yoo JJ. The in vivo stability of electrospun polycaprolactone-collagen scaffolds in vascular reconstruction. Biomaterials. 2009;30:583–588. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shalaby WSW, Blevins WE, Park K. Use of ultrasound imaging and fluoroscopic imaging to study gastric retention of enzyme-digestible hydrogels. Biomaterials. 1992;13:289–296. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(92)90052-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zeng J, Yang L, Liang Q, Zhang X, Guan H, Xu X, Chen X, Jing X. Influence of the drug compatibility with polymer solution on the release kinetics of electrospun fiber formulation. Journal of Controlled Release. 2005;105:43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2005.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tanizawa A, Fujimori A, Fujimori Y, Pommier Y. Comparison of topoisomerase I inhibition, DNA damage, and cytotoxicity of camptothecin derivatives presently in clinical trials. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1994;86:836–842. doi: 10.1093/jnci/86.11.836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brem H. Polymers to treat brain tumours. Biomaterials. 1990;11:699–701. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(90)90030-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]