Abstract

To take complete advantage of information on within-species polymorphism and divergence from close relatives, one needs to know the rate and the molecular spectrum of spontaneous mutations. To this end, we have searched for de novo spontaneous mutations in the complete nuclear genomes of five Arabidopsis thaliana mutation accumulation lines that had been maintained by single-seed descent for 30 generations. We identified and validated 99 base substitutions and 17 small and large insertions and deletions. Our results imply a spontaneous mutation rate of 7 × 10−9 base substitutions per site per generation, the majority of which are G:C→A:T transitions. We explain this very biased spectrum of base substitution mutations as a result of two main processes: deamination of methylated cytosines and ultraviolet light–induced mutagenesis.

Most of what we know about molecular evolution comes from the comparison of biological sequences that have survived many cycles of natural selection. In order to infer the properties of the original source of variation and to detect the signature of natural selection from such data sets, we need to assume that variants affecting certain types of sites, such as the last base of fourfold redundant codons or pseudogenes, are not subject to natural selection. This pervasive assumption is very rarely tested and difficult to avoid, because of the slow pace of spontaneous mutagenesis. However, with the advent of high-throughput sequencing technologies, some estimates of the rate of spontaneous mutations have begun to appear (1–3). Here, we report a direct estimate of the spontaneous base substitution rate in Arabidopsis thaliana, a plant species with extensive DNA methylation. As a result, we reduce the uncertainty associated with key aspects of the evolutionary history of this species, including the time since divergence from A. lyrata and the effect of methylation on the probability of mutation.

We sequenced the genomes of five individuals derived by 30 generations of single-seed descent from the reference strain Col-0 (4), for which a high-quality genome was published in 2000 (5). We used the Illumina (Illumina, San Diego, CA) Genome Analyzer platform to obtain a depth of sequence coverage of between 23 and 31 in each mutation accumulation (MA) line. Sequencing reads between 36 and 43 base pairs (bp) in length were aligned to the reference genome, from which over 1000 errors had been removed in a previous study (6). We identified single-base substitutions using two complementary methods: a “consensus” approach and the single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) caller function of SHORE (http://1001genomes.org/ downloads/shore.html) (7).

In the consensus approach, base substitutions were called if one of the MA lines differed from all others. We estimated a frequency of sequencing errors of ~0.3% per site per read (8). We assumed a binomial distribution of errors to derive the probabilities of false positives and false negatives, and we corrected our estimates accordingly (9). Because sequencing and mapping errors are not randomly distributed among sites (3), we used strict quality filters to exclude from analysis sites suspected to have higher error rates (8). Between 93 and 95 million sites out of the 120 million–bp reference genome matched the quality requirements in each line. Across all five lines, 85 single-base substitutions were called by this method, 83 of which were confirmed by Sanger sequencing. In the other two sites, two or three lines had a nonreference base, whereas the rest matched the reference, and we interpret this to be a result of differential fixation of the two alleles present in ancestrally heterozygous sites rather than as parallel mutations, although the latter cannot be ruled out.

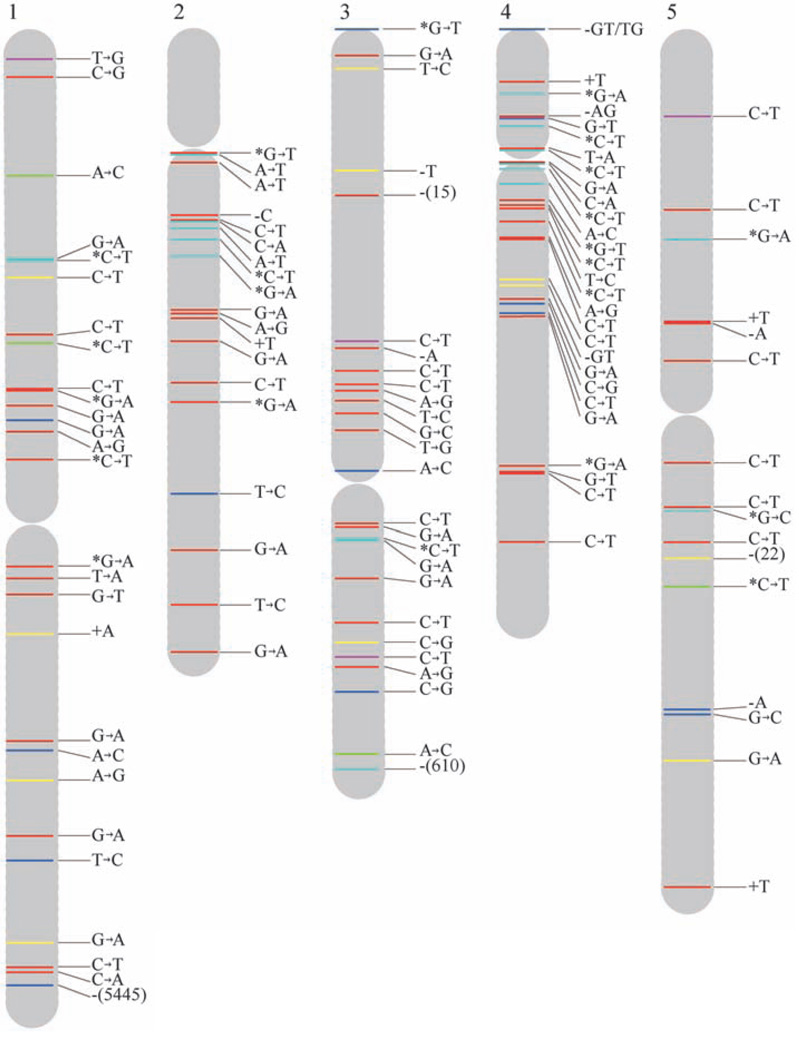

In addition to this conservative approach, we used SHORE to detect single-base substitutions, short insertions and deletions (indels) of up to 3 bp, and long deletions. The algorithms implemented in SHORE are more sensitive (8), and between 98.8 and 100.9 million sites in each line had sufficient read information for calling either a mutation or the reference base. We detected 99 single-base substitutions (98 of which were confirmed by Sanger sequencing, and 1 was rejected because the reference base was revealed), 9 short deletions (8 confirmed, 1 rejected), 5 short insertions of 1 bp (all confirmed), and 8 long deletions covering11 toover 5000bp (4confirmed, 2 ambiguous, and 2 rejected). A 2-bp deletion was shown to be present in two lines, suggesting that it was heterozygous in the ancestral line. The chromosomal positions of all validated mutations are shown in Fig. 1. Both false positives and false negatives are expected to be absent from the final set of simple base-substitution mutations (8). Fifteen sites where all MA lines had a common composition, but different from the reference, including 13 single-base substitutions and two deletions of 1 and 2 bp, were interpreted as fixed mutations in the ancestral line.

Fig. 1.

Distribution of spontaneous mutations across chromosomes. Labels indicate the type of mutation and colors their functional context or predicted effect. Short insertions and deletions are shown by the letters representing the affected bases preceded by a plus or aminus sign, respectively. Long deletions are depicted by aminus sign and the number of deleted base pairs in parentheses. An asterisk next to a C or a G means that the cytosine of the mutant base pair is known to be methylated (20). The definitions for colors are as follows: red, intergenic region; yellow, intron; dark blue, nonsynonymous substitution, shift of reading frame for short indels, or gene deletion for large deletions; green, synonymous substitution; purple, UTR; and light blue, transposable element.

We estimated the overall mutation rate to be 5.9 × 10−9 ± 0.6 × 10−9 base substitutions per site per generation according to the consensus approach and 6.5 × 10−9 ± 0.7 × 10−9 according to SHORE. In addition, joint maximum-likelihood estimates of the overall mutation rate and the sequencing error frequency were obtained following a recently developed method (9). With this approach, a slightly higher mutation rate of 7.1 × 10−9 ± 0.7 × 10−9 at a slightly lower error frequency of 0.2% was estimated. Mutations were evenly distributed among MA lines (Table 1). Within chromosomes, a significantly higher base-substitution mutation rate for intergenic regions was observed closer to the centromere (within 3.0 × 106 bp, for example) than farther away (Fisher’s exact test, P value = 0.01, for nonmethylated sites).

Table 1.

Number of mutations inferred by SHORE and validated by Sanger sequencing, their distributions among functional classes in each MA line, and totals.

| MA line | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 29 | 49 | 59 | 69 | 119 | Total | |

| Intergenic | 8 | 11 | 12 | 10 | 14 | 54 |

| Mobile elements | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 17 |

| UTR | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 4 |

| Intron | 3 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Synonymous | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| Nonsynonymous | 1 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 11 |

| All mutations | 17 | 18 | 23 | 18 | 22 | 98 |

| Mutation rate (×10−9) | 5.7 | 6.0 | 7.6 | 5.9 | 7.4 | 6.5 |

| Standard error (×10−9) | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.6 | 1.4 | 1.6 | 0.7 |

The estimated rates of 1- to 3-bp deletions and insertions are 0.6 × 10−9 ± 0.2 × 10−9 and 0.3 × 10−9 ± 0.1 × 10−9 per site per generation, respectively. Out of the 13 short indels that we observed, 6 were found in complex sequences, corresponding to a mutation rate of 4.0 × 10−10 ± 1.6 × 10−10 indels per site per generation, or about 0.05 ± 0.02 indels per haploid genome per generation, excluding homopolymers and micro-satellites. This estimate should be considered a lower bound, given the unknown level of false negatives among indels. The short-read sequencing approach is less well-suited for the analysis of dinucleotide repeats, because the most frequent class of dipolymers (AT/TA) has low read coverage, most likely resulting from the sequencing library construction protocol (10) (fig. S1). Deletions larger than 3 bp occurred at a frequency of 0.5 × 10−9 ± 0.2 × 10−9 per site per generation and removed on average 800 ± 1900 bp per event.

The preceding estimates, together with the recently published rate of mutation at dinucleotide microsatellites (11), give an almost complete view of the spectrum of spontaneous mutations in A. thaliana (Table 2).Our estimate of themutation rate is close to the lower bound of an indirect estimate based on the divergence between monocots and dicots (12). If we assume that only nonsynonymous mutations and indels affecting coding regions are likely to affect fitness, the diploid genomic rate of mutations affecting fitness would be 0.2 ± 0.1 per generation, which is not significantly different from previous estimates based on the evaluation of fitness components in MA lines of A. thaliana (13, 14). Alternatively, the proportion of deleterious mutations among mutations in coding regions can be estimated from sequence comparisons between A. thaliana and A. lyrata (8, 15). Using that information, the estimated genomic deleterious mutation rate is 0.14 ± 0.04 per generation.

Table 2.

Haploid mutation rates per genome per generation and standard errors (SEM). Estimates for indels in dinucleotide repeats comes from Marriage and colleagues (11) and are the product of their per-locus per-generation mutation rate and the number of perfect repeats in the genome.

| Mutation type | Rate | SEM |

|---|---|---|

| A:T→G:C | 0.09 | 0.03 |

| C:G→T:A | 0.41 | 0.06 |

| A:T→T:A | 0.04 | 0.02 |

| C:G→A:T | 0.06 | 0.02 |

| A:T→C:G | 0.04 | 0.02 |

| C:G→G:C | 0.05 | 0.02 |

| Complex sequence | 0.05 | 0.02 |

| AT repeats | 19.12 | 1.77 |

| AG repeats | 2.40 | 0.55 |

| AC repeats | 0.13 | 0.09 |

| Large deletions (>3 bp) | 0.03 | 0.02 |

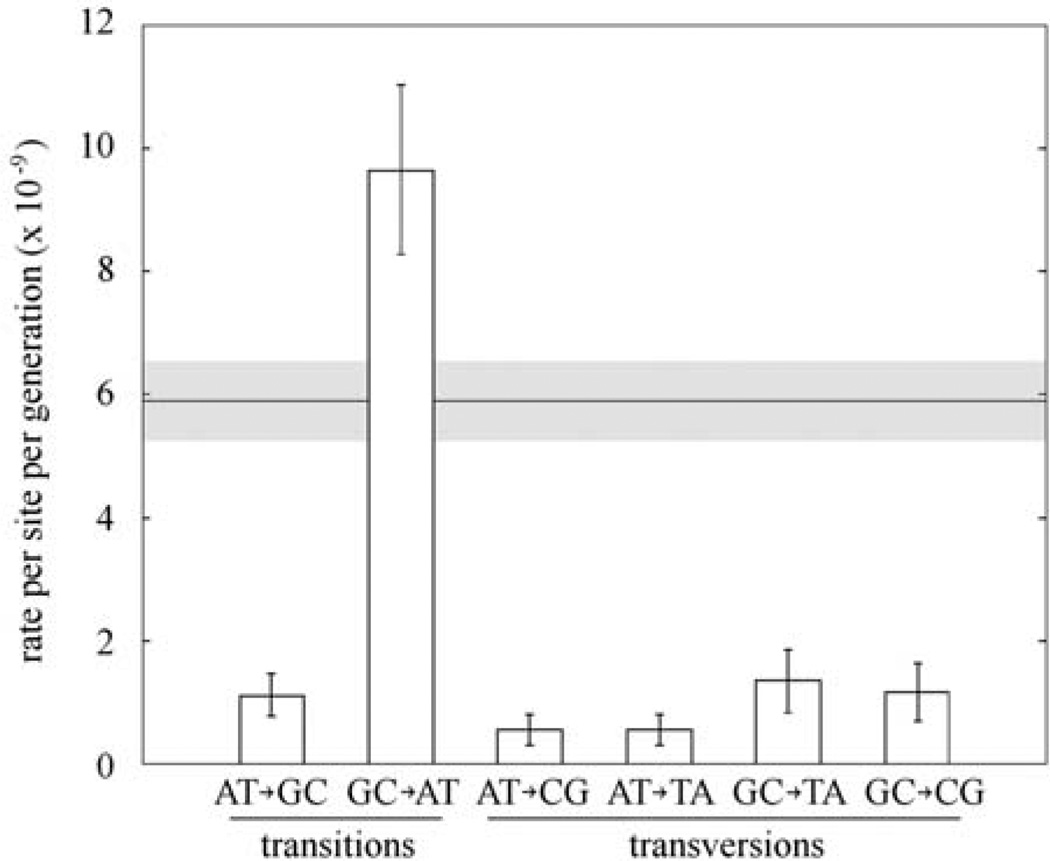

We did not detect any difference between the “unpolarized” (8) spectrum of base-substitution mutations and the genome-wide spectrum of polymorphisms at synonymous sites surveyed in natural populations by two independent studies (6, 16) (fig. S2; Fisher’s exact test, P = 0.4 and P = 0.7, respectively). Transitions were 2.4 times more frequent than transversions, and G:C→A:T transitions, most of which are silent at the third codon position, were by far the most frequent type of mutations (Fig. 2). Under the observed mutational spectrum, the base-composition equilibrium achieved only by mutation would be 85% A+T, which is far from the current 68% observed in intergenic and intronic regions and from the 65% in fourfold redundant coding sites across the A. thaliana genome. Whether selection is preventing a further increase in A+T content, or whether the genome is still evolving toward a higher A+T content, is not known.

Fig. 2.

Conditional mutation rates per A:T or G:C site per generation. Complementary mutations, such as A→C and T→G, are pooled. Error bars indicate standard errors of the mean. The overall mutation rate, which is the average of the total mutation rates at A:T and G:C sites, and its standard error in gray are shown in the background. Only estimates from the consensus method are shown.

Spontaneous deamination of methylated cytosine, which leads to thymine substitution (17–19), is thought to be a major source of mutations. Thus, we exploited a single base–resolution methylation map of the A. thaliana genome (20) to test whether cytosine methylation can account for the overabundance of G:C→A:T transitions. G:C sites where the cytosine has been reported to be at least partially methylated had a higher probability of mutation to A:T than nonmethylated sites (Fisher’s exact test, P = 3.2 × 10−7). However, 91% of G:C sites in A. thaliana were not reported to be methylated, and they too had a higher rate of transition (but not transversion) than A:T sites (Fisher’s exact test, P = 1.2 × 10−8). G:C sites in CpG contexts are known to be more frequently methylated (20, 21). However, transitions at G:C sites not known to be methylated do not happen in CpG contexts more often than expected by chance (Fisher’s exact test, P = 0.6). This suggests that factors in addition to methylation contribute to the high rate of transitions atG:C sites.

In both prokaryotes and eukaryotes, most of the mutations caused by ultraviolet (UV) light are G: C→A:T transitions at sites where the C is adjacent to another C or to a T (dipyrimidine sites) (22). Among the 33 observed transition mutations at nonmethylated G:C sites, 31 were in dipyrimidine contexts, which is more than expected by chance at the P = 0.02 level (Fisher’s exact test). Thus, we conclude that the increased rate of transitions at G:C sites, relative to A:T sites, can be largely explained by the combined effect of UV-induced mutagenesis and deamination of methylated cytosines. This implies that the mutation rate in nature could be higher than that reported here, becauseUVradiation during the MA experiment was probably lower than in natural conditions.

We used the Arabidopsis Information Resource (TAIR) 8 annotation (www.arabidopsis.org) to group all analyzed sites into the functional classes: intergenic, intronic, untranslated region (UTR), coding, pseudogene, mobile element, and noncoding. There is no deficit of nonsynonymous mutations (G test, P = 0.4), supporting the notion that themutation rate we observed is not affected by selection. We did, however, observe an excess of intergenic mutations, relative to mutations in coding regions, introns, and UTRs (fig. S3). These differences were still significant after taking into account the effects of base composition and methylation (G test, P = 0.00025). To test whether the lack of mutations in genic regions was due to undetected levels of selection, we compared the intergenic mutation rate with the rate at synonymous sites and introns, which are less likely to be under strong selection, andwe still detected a significant deficit of mutations in the latter (Fisher’s exact test, P=0.001, for nonmethylated sites). We attribute the deficit of genic mutations to our observation of a higher mutation rate in pericentromeric regions (see above), where gene density is lower (5), although transcription-coupled DNA repair could also contribute to the pattern. Lastly, the finding of a higher mutation rate in pericentromeric regions provides an explanation of the Arabidopsis-specific pattern of higher polymorphism levels near the centromeres (16, 23), although the underlying mechanism of such a mutational bias remains to be explained.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank C. Lanz for generating the Illumina data, S. E. Jacobsen for providing the methylation data, and P. Tiffin for valuable comments. Funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) (ERA-PG ARelatives), a Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz Award (DFG), the Max Planck Society (D.W.), NIH grant GM36827 to M. L. and W. Kelly Thomas, Pioneer Hi-Bred International to E. Darmo, and NSF grants DEB 9629457 and 9981891 to R.G.S.

Footnotes

Supporting Online Material

www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/327/5961/92/DC1

Materials and Methods

SOM Text

Figs. S1 to S8

Tables S1 to S3

References

References and Notes

- 1.Lynch M, et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2008;105:9272. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Denver DR, et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2009;106:16310. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904895106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keightley PD, et al. Genome Res. 2009;19:1195. doi: 10.1101/gr.091231.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shaw RG, Byers DL, Darmo E. Genetics. 2000;155:369. doi: 10.1093/genetics/155.1.369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arabidopsis Genome Initiative. Nature. 2000;408:796. doi: 10.1038/35048692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ossowski S, et al. Genome Res. 2008;18:2024. doi: 10.1101/gr.080200.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schneeberger K, et al. Genome Biol. 2009;10:R98. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-9-r98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Materials and methods are available as supporting material on Science Online.

- 9.Lynch M. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2008;25:2409. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msn185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Quail MA, et al. Nat. Methods. 2008;5:1005. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marriage TN, et al. Heredity. 2009;103:310. doi: 10.1038/hdy.2009.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wolfe KH, Li W-H, Sharp PM. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1987;84:9054. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.24.9054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schultz ST, Lynch M, Willis JH. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1999;96:11393. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.20.11393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shaw FH, Geyer CJ, Shaw RG. Evolution. 2002;56:453. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2002.tb01358.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wright SI, Lauga B, Charlesworth D. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2002;19:1407. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a004204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clark RM, et al. Science. 2007;317:338. doi: 10.1126/science.1138632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lindahl T, Nyberg B. Biochemistry. 1974;13:3405. doi: 10.1021/bi00713a035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coulondre C, Miller JH, Farabaugh PJ, Gilbert W. Nature. 1978;274:775. doi: 10.1038/274775a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duncan BK, Miller JH. Nature. 1980;287:560. doi: 10.1038/287560a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cokus SJ, et al. Nature. 2008;452:215. doi: 10.1038/nature06745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lister R, et al. Cell. 2008;133:523. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Friedberg EC, et al. DNA Repair and Mutagenesis. Washington, DC: ASM (American Society for Microbiology) Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kawabe A, Forrest A, Wright SI, Charlesworth D. Genetics. 2008;179:985. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.085282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.