Abstract

Several features make the chromatin environment of neurons likely to be different than any other cell type. These include the fact that several hundred types of neurons exist, each requiring specialized patterns of gene expression and in turn specialized chromatin landscapes. In addition, neurons have the most stable morphology of any cell type, a unique feature essential for memory. Yet these stable morphologies must allow the emergence of new stable morphologies in response to environmental influences permitting learning to occur by altered morphology and new synapse formation. Several years ago we found that neurons have specific chromatin remodeling mechanisms not present in any other cell type that are produced by combinatorial assembly of ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling complexes. The neural specific subunits are essential for normal neural development, learning and memory. Remarkably, recreating these neural specific complexes in fibroblasts leads to their conversion to neurons. Recently, the subunits of these complexes have been found to have genetically dominant roles in several human neurologic diseases. The genetic dominance of these mutations suggests that less severe mutations will contribute to phenotypic variation in human neuronally derived traits.

Introduction

Several hundred types of neurons are present in mammals that are united by common characteristics including axons, dendrites, synapse formation and almost always a need for a remarkably stable morphology. Indeed, in certain species such as the long-lived Bowhead whale, dendritic morphologies might persist for over 200 years. Yet these stable morphologies must be modified to allow learning. One mechanism of maintaining a stable morphology would be to stabilize gene expression, particularly of genes involved in maintaining cytoskeletal features that underlie axon and dendrite formation. Such stabilization of gene expression might be produced by specialized chromatin regulatory mechanisms that also have the ability to be activated to allow new morphologies and synaptic plasticity in response to learning. Several years ago we began looking for such chromatin regulatory mechanisms and found that neurons do indeed have specialized chromatin remodeling complexes not found in any other tissue and that these complexes are necessary to convey signals produced by action potentials to regulate genes in the nucleus [1•,2,3••,4]. We will focus this brief review on the biochemistry and genetics in mice and humans of these neuron specific chromatin regulators know as npBAF and nBAF in neural progenitors and neurons respectively.

Chromatin regulation

The mechanisms involved in packaging around 2 m of DNA into a 5 μm nucleus, while retaining the ability to replicate and selectively express genes has been the focus of much of chromatin biology. At least three mechanisms are thought to be involved in this process including DNA methylation, histone modification and ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling. In vertebrates 29 known genes encode the ATPases of chromatin remodeling complexes; most of which have not been extensively characterized [5]. These ATPase complexes are generally thought to promote accessibility of regulatory DNA sequences by using the energy provided by the core ATPase to increase nucleosome mobility. This review will focus on ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling by complexes based on the Brg and Brm ATPases, which are alternative subunits of BAF (Brg/Brm Associated Factors) aka mSWI/SNF complexes. In higher vertebrates these complexes are produced by combinatorial assembly of subunits encoded by gene families resulting in many possible complexes, some of which are found only in the nervous system. In mammals the neural specific npBAF and nBAF complexes have 15 subunits encoded by 28 genes (Figure 1). Six of the 15 subunits are encoded by genes that have homologs in the yeast SWI/SNF complex, while the other subunits are of more recent evolutionary origin [6•]. When we initially purified the mammalian complexes [1•,3••,4,7•,8,9,10•, 11•, 12] we first called them mammalian or mSWI/SNF; however, upon more extensive study we learned that most of the subunits do not have yeast homologs and therefore prefer the nomenclature: BAF-molecular weight. The official HUGO nomenclature, Swi/Snf-like, Matrix associated, Actin-dependent Regulator of Chromatin (SMARC) was derived from our initial observation that the complexes contained β-actin and bound to the nuclear matrix fraction. Unfortunately, the SMARC nomenclature was extended to other proteins that are not associated with β-actin and are not matrix-associated.

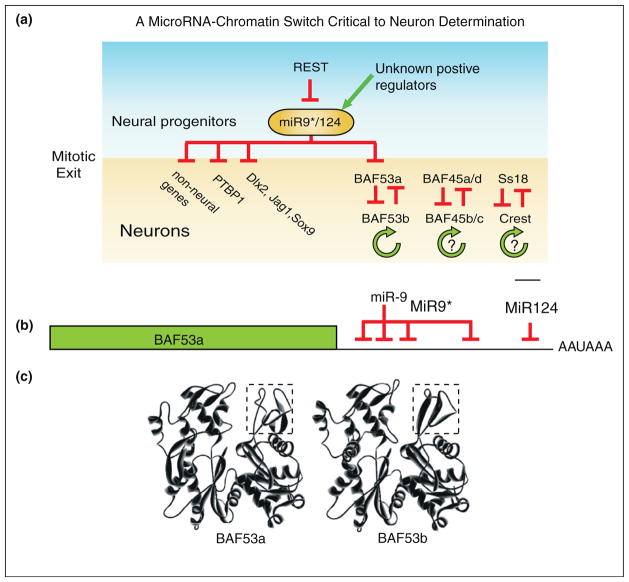

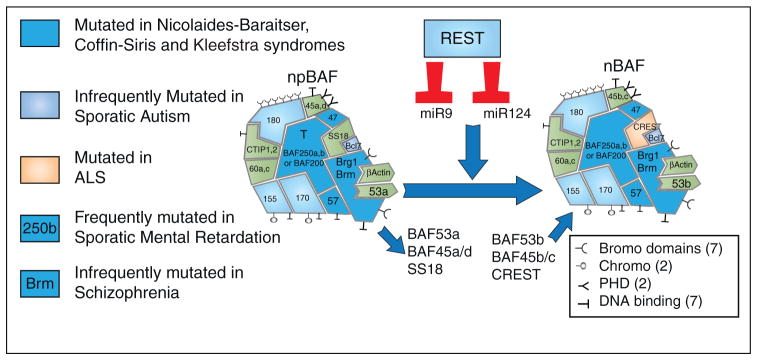

Figure 1.

BAF complexes switch subunits when REST protein levels decrease relieving repression on miR-9* and miR-124 which both repress BAF53a. Exome sequencing has implicated different subunits (indicated by color) in the human diseases indicated on the left. Note the large number of domains that recognize histone modifications and bind DNA directly and hence could target the complexes to different genomic loci without the need for DNA binding proteins.

The development of the nervous system is accompanied by sequential changes in chromatin remodeling mechanisms

As pluripotent embryonic stem (ES) cells develop to multi-potent neural progenitors and later to neurons, BAF complexes undergo sequential changes from esBAF to npBAF to nBAF (Figure 1). Pluripotent ES cells require the expression of esBAF chromatin remodeling complexes to fine-tune the expression of pluripotency genes such as Oct4 and Sox2 [13]. esBAF complexes are characterized by the presence of Brg, BAF250a, BAF155, BAF60a and 60b and the absence of Brm, BAF250b, BAF170, and BAF60c [11•]. Mutation of the genes selectively expressed in esBAF complexes leads to loss of pluripo-tency and preimplantation lethality, while the alternative subunits are dispensable for pluripotency and instead produce specific phenotypes later in development [1,2,14•,15••,16•,42••]. As ES cells are induced to differentiate into neurons these complexes begin to switch subunits with the initial appearance of BAF45c, BAF60c and BAF250b in neural progenitors eventually leading to a specific subunit composition in neurons, which to date has not been detected in any other cell type. Presently, it appears that no other chromatin remodeling mechanism is specific only to neurons, raising the question of the role of nBAF complexes in the nervous system. Interestingly, the neural specific subunits, BAF53b, BAF45b, BAF45c and CREST arose most recently in higher vertebrates, perhaps corresponding to the need for a more complex vertebrate nervous system. However, the role of BAF complexes in denditic morphogenesis is evolutionarily conserved as genetic screens in Drosophila for genes that perturb den-dritic patterns have identified orthologues of six BAF subunits [17••,18•].

Switching from the neural progenitor to the neural BAF complexes is controlled by a triple negative genetic switch

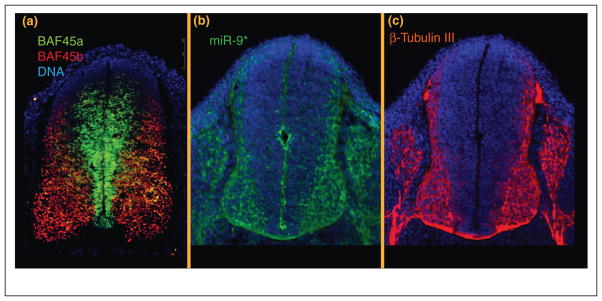

The switch of three subunits from npBAF to nBAF is remarkably precise with little over lap in expression patterns (Figure 2). The switch corresponds to mitotic exit and it appears that the switch must happen within one cell generation and perhaps within only a fraction of the last cell cycle. Removal of BAF53a, BAF45a or SS18 leads to cell cycle exit, while forcing the expression of the BAF45a subunit leads to additional cell cycles [3••,4]. Thus it appears one of the roles of the npBAF complex is to promote cell cycle progression. Deletion of the post mitotic subunits leads to developmental failure of neuronal specific traits such as dendritic morphogenesis and synapotogenesis with death at birth due to a failure to nurse [2,16•]. These genetic findings told us that the switching mechanism is critical to neural development, but what brought about the switch?

Figure 2.

(a) Mutually exclusive expression of BAF45a and BAF45b in the murine neural tube at E11.5. Proliferating cells lining the neural tube ventricle contain BAF complexes with BAF45a, while post mitotic neurons contain BAF complexes with BAF45b. (b) Expression of miR-9* (green) [19••]. Note that miR-9* is first expressed along the ventricle of the developing neural tube, in what is probably the last progenitor cell division and then continues to be expressed as new-born neurons migrate laterally through the progenitor zone into the (c) b-Tubulin III positive post mitotic zone. MiR-124 has been shown to be expressed in a similar pattern [21]. Thus both miR-9* and miR-124 are first activated just before the repression of BAF53a, BAF45a, and SS18 which is consistent with the genetic circuitry shown in Figure 3.

To uncover the mechanism underlying subunit switching we assumed that it would be controlled by a transcriptional switch. We analyzed BAF53a cis-regulation using carefully designed Bacterial Artificial Chromosomes-transgenic reporter mouse embryos. Surprisingly, all developmental regulation mapped to the evolutionarily conserved 3′ untranslated region (UTR) of BAF53a [19••]. Further analysis of the BAF53a 3′UTR lead to the realization that the critical sequences for BAF53a repression were predicted binding sites of the micro-RNA’s miR-9* and miR-124 and that binding sites for both were required for full repression of BAF53a (Figure 3). The requirement of two microRNA’s functions like a molecular ‘AND’ switch where both miR-9* and miR-124 function synergistically and are simultaneously required for full repression of BAF53a (reviewed in [20]). MiR-9* and miR-124 are activated at the last mitotic division of neural progenitors in the cells lining the ventricles and in post mitotic neurons (Figure 2) [21]. This expression pattern nicely fits the disappearance of BAF53a, during the final neural progenitor division that is often asymmetric, generating a neural progenitor and a neuron. Thus as miR-9* and miR-124 appear, BAF53a is repressed. This turn of events focused attention on the regulators of miR-9* and miR-124. These microRNA’s are each encoded by 3 genes and are under negative regulation by the transcriptional repressor REST [22]. REST restricts the expression of neuronal genes by repressing neuronal genes in non-neuronal cells. REST probably does not account for all of the repression of miR-9* and miR-124 because the level of repression produced by REST is about 3-fold to 5-fold, while miR-9* and miR-124 are activated several hundred fold at the time of the last mitotic division (Figure 2) [4,22]. This told us something about how BAF53a was repressed by miR-9*/miR-124, but what gave rise to the activation of the nBAF subunit BAF53b, which replaces BAF53a?

Figure 3.

A MicroRNA/chromatin switch is required for mammalian neural development. (a) Summary of regulatory relationships by which miR-9* and miR-124 control neuronal specific splicing, Notch signaling and neuronal specific chromatin. The positive autofeedback mechanisms shown with a ‘?’ indicate that they are not validated. (b) MiR-9* and miR-124 bind to three sites in the BAF53a 3′UTR and silence it near mitotic exit. (c) Predicted structures of BAF53a and BAF53b showing that subdomain 2 (shown in the box) is the most divergent region [43].

In part the activation of BAF53b at mitotic exit appears to be due to protein stability. When BAF53b is deleted we find that BAF53a attempts to take its place and persist into adult post mitotic neurons (unpublished results). However, replacing BAF53b with BAF53a is not sufficient to rescue lethality, because a unique protein domain of BAF53b (subdomain 2 shown in box in Figure 3c) is essential for dendritic morphogenesis, a function that cannot be replaced by BAF53a [2]. These observations lead us to propose a triple negative genetic switch, which drives the conversion of npBAF to nBAF (Figure 3a). It should be noted that this switch is coordinated with the replacement of a general splicing factor PTBP1 by a neural specific homolog that affects splicing patterns in neurons [21].

Recapitulating the micro-RNA/chromatin switch converts human fibroblasts to neurons

During the course of these studies aimed at defining the genetic circuitry underlying epigenetic switching we noted that co-expression of miR-9* and miR-124 in non-neuronal cell types caused the cells to take on neuronal morphologies, express MAP-2 and activate each of the neuronal specific nBAF subunits: BAF45b, BAF45c, BAF53b and CREST. However, co-expression of miR9* and miR-124 alone converted cells with low efficiency (<5%) so neurogenic transcription factors were expressed with the miRNA’s. MiR-9*/miR-124 plus Neu-roD2 increased the frequency of conversion to MAP2+ neurons to 50% and closer inspection of the converted human fibroblasts revealed that they produce functional synapses that take up synaptic components and in turn release them upon depolarization [23••]. The converted cells also made action potentials, but few developed repetitive action potentials. Thus the cells converted with miR-9*/miR-124 and NeuroD2 appeared to be immature neurons. Pioneering studies done in the laboratory of Marius Wernig provided a key helper factor. Wernig and colleagues had systematically examined the transcription factors that might convert fibroblasts into neurons in much the same way that Yamanaka and colleagues defined factors that could convert fibroblasts to IPS cells [24]. Their studies defined a group of transcription factors that when overexpressed in mouse fibroblasts lead to neuronal conversion, most remarkably they found that a combination of four transcription factors would produce fully functional, mature murine neurons [25••]. These observations lead us to try a combination of miR-9*/miR-124, NeuroD2, Ascl1 and Myt1L which turned out to be particularly effective at converting human fibroblasts to fully functional and mature neurons that made repetitive action potentials [23••]. Interestingly, miR-9*/miR-124 mediated conversion worked much better with human cells and could reprogram dermal fibro-blasts from individuals as old as 45, the oldest sample we tested. In contrast, the transcription factor mediated conversion worked better with murine cells and was not effective to convert the fibroblasts of older individuals [25••,26]. The mechanisms involved in the conversion of fibroblasts to neurons by this microRNA/chromatin switch have been recently reviewed [27].

Mutations in BAF subunits have genetically dominant roles in human intellectual disability

If the npBAF to nBAF genetic switch was a major determinant of the neuronal state then one might expect that mutations in its components would produce human neurologic disease. Within several months of our discovery of the instructive role of this circuitry in neuronal determination, human exome sequencing studies of neurologic diseases began to reveal that mutations in components of this circuitry were targets of several human neurologic diseases (Table 1). The first disease to be associated with mutations in BAF subunits was Nicolaides–Baraitser syndrome (NCBRS), which is characterized by marked language impairment, intellectual disability, occasional microcephally, growth deficiency, coarse facial features, hair abnormalities (hypertrichosis and sparse scalp hair) and digit abnormalities [28••,29]. Thirty-six of 44 individuals with NCBRS had a missense or in-frame deletion of BRM. Very shortly after these reports, individuals with Coffin–Siris syndrome (CSS) were found to have mutations in one of 5 BAF subunits BAF250A, BAF250B, Brg, BAF57 and BAF47 [30••,31••,44,45]. Although CSS and NCBRS are different clinical entities, they are both characterized by intellectual disability, hair abnormalities and digit abnormalities (with CSS individuals exhibiting hypoplas-tic/absent fifth fingernails). Further, additional sequencing efforts revealed that mutation of one allele of BAF250b accounted for a very significant percentage, 0.9%, of sporadic intellectual disability [32•,33,34]. In each case the mutations involved appeared to occur on only one allele indicating they are genetically dominant. Closer inspection of the actual BAF250a or BAF250b mutations indicates that all are non-sense or frameshift mutations or whole-gene deletions predicted to produce no protein indicating that they can be haploinsufficient. In contrast many of the NCBRS BRM and CSS Brg mutations are missense changes that cluster to the ATP binding and helicase domains suggesting that they might produce a structurally unchanged but catalytically compromised dominant negative or a minor reduction in function of BRM or Brg and hence the BAF complexes. On the basis of the prevalence of BAF subunit mutations in CSS and sporadic intellectual disability it has been suggested that up to 3% of unexplained intellectual disability might be caused by mutations in genes encoding BAF subunits [30••,33,35]. The genetic dominance is consistent with studies in mice, where heterozygous mice with null mutations of Brg or Baf155 show neural developmental phenotypes such as a failure of neural tube closure [14•,36].

Table 1.

BAF subunit mutations found in individuals with intellectual disabilities and neurological disease

| Disease | Human gene | BAF subunit | Position | CDS mutation | AA mutation | Type of mutation | Inheritance | Mutation count | PMID | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALS | CREST | CREST | 123 | c.369T>G | p.Ile123Met | Substitution_missense | family history | 1 | 23708140 | Chesi et al. [42••] |

| ALS | CREST | CREST | 388 | c.1162C>T | p.Gln388* | Substitution_nonsense, deletes last 9aa | de novo | 1 | 23708140 | |

| ASD | SMARCC1 | BAF155 | 742 | c.2225A>G | p.Gln742Arg | Substitution_missense | family history | 1 | 22495311 | Neale et al. [38] |

| ASD | SMARCC2 | BAF170 | c.1770+1;c.1863+1 | Splice Site | de novo | 1 | 22495311 | |||

| ASD | PBRM1 | BAF180 | 763 | p.Asp763Gly | Substitution_missense | de novo | 1 | 22495309 | O’Roak et al. [37] | |

| ASD | ARID1B | BAF250B | 514 | chr6:157,192,247_157,473,298del | p.514fs*20_0.2 Mb deletion_exons 4–6 | Deletion_frameshift | de novo | 1 | 21448237 | Nord et al. [46] |

| ASD | ARID1B | BAF250B | 1797 | chr6:157527664 | p.Leu1797fs | Frameshift | de novo | 1 | 22495309 | |

| ASD | REST | REST | 993 | c.2978C>G | p.Pro993Arg | Substitution_missense | de novo | 1 | 22495311 | |

| CSS | SMARCB1 | BAF47 | 363 | c.1089G>T | p.Lys363Asn | Substitution_missense | de novo | 1 | 23929686 | Santen et al. [44] |

| CSS | SMARCB1 | BAF47 | 364 | c.1091_1093del AGA | p.Lys364del | Deletion_inframe | de novo, 6/9. nc, 3/9 | 9 | 22426308/23815551/23929686 | Tsurusaki et al. [30••]/Tsurusaki et al. [45] |

| CSS | SMARCB1 | BAF47 | 377 | c.1130G>A | p.Arg377His | Substitution_missense | de novo | 1 | 22426308 | |

| CSS | SMARCE1 | BAF57 | 73 | c.218A>G | p.Tyr73Cys | Substitution_missense | de novo | 1 | 22426308 | |

| CSS | SMARCE1 | BAF57 | 105 | c.314G>A | p.Arg105Gln | Substitution_missense | in affected mother | 1 | 23929686 | |

| CSS | SMARCA4 | Brg | 450 | c.1349C>A | p.Ala450Asp | Substitution_missense | de novo | 1 | 23929686 | |

| CSS | SMARCA4 | Brg | 458 | c.1372_1395del | p.Lys458_Glu465del | Deletion_inframe | de novo | 1 | 23815551 | |

| CSS | SMARCA4 | Brg | 546 | c.1636_1638del AAG | p.Lys546del | Deletion_inframe | de novo | 1 | 22426308 | |

| CSS | SMARCA4 | Brg | 859 | c.2576C>T | p.Thr859Met | Substitution_missense | de novo | 1 | 22426308 | |

| CSS | SMARCA4 | Brg | 885 | c.2653C>T | p.Arg885Cys | Substitution_missense | de novo | 1 | 22426308 | |

| CSS | SMARCA4 | Brg | 885 | c.2654G>A | p.Arg885His | Substitution_missense | de novo | 1 | 23815551 | |

| CSS | SMARCA4 | Brg | 921 | c.2761C>T | p.Leu921Phe | Substitution_missense | de novo | 1 | 22426308 | |

| CSS | SMARCA4 | Brg | 1011 | c.3032T>C | p.Met1011Thr | Substitution_missense | de novo | 1 | 22426308 | |

| CSS | SMARCA4 | Brg | 1043 | c.3127C>T | p.Arg1043Trp | Substitution_missense | de novo | 1 | 23929686 | |

| CSS | SMARCA4 | Brg | 1127 | c.3380A>G | p.Asp1127Gly | Substitution_missense | not in mother | 1 | 23929686 | |

| CSS | SMARCA4 | Brg | 1157 | c.3469C>G | p.Arg1157Gly | Substitution_missense | de novo | 1 | 22426308 | |

| CSS | SMARCA4 | Brg | 1203 | c.3608G>A | p.Arg1203His | Substitution_missense | nc | 1 | 23929686 | |

| CSS | ARID1A | BAF250A | 11 | c.31_56del | p.Ser11Alafs*91 | Deletion_frameshift | nc | 1 | 22426308 | |

| CSS | ARID1A | BAF250A | 920 | c.2758C>T | p.Gln920* | Substitution_nonsense | nc | 1 | 22426308 | |

| CSS | ARID1A | BAF250A | 1335 | c.4003C>T | p.Arg1335* | Substitution_nonsense | de novo | 1 | 22426308 | |

| CSS | ARID1A | BAF250A | 1113 | c.1113del | p.Gln372Serfs*19 | Deletion_frameshift | de novo | 1 | 23929686 | |

| CSS | ARID1A | BAF250A | 3679 | c.3679G>T | p.Glu1227* | Substitution_nonsense | de novo | 1 | 23929686 | |

| CSS | ARID1A | BAF250A | 6493 | c.6493G>T | p.Glu2165* | Substitution_nonsense | Not in father | 1 | 23929686 | |

| CSS | ARID1A | BAF250A | 6532 | c.6532del | p.Asp2178Thrfs*22 | Deletion_frameshift | nc | 1 | 23929686 | |

| CSS | ARID1B | BAF250B | exons 1–20 | Whole gene deletion | p.0 | Deletion | nc | 1 | 23929686 | |

| CSS | ARID1B | BAF250B | 408 | c.1222dup | p.Gln408Profs*127 | Deletion_frameshift | de novo | 1 | 23929686 | |

| CSS | ARID1B | BAF250B | 413 | c.1235dup | p.Ser413Valfs*122 | Deletion_frameshift | de novo | 1 | 23929686 | |

| CSS | ARID1B | BAF250B | 420 | c.1259dup | p.Asn420Lysfs*115 | Deletion_frameshift | de novo | 1 | 23929686 | |

| CSS | ARID1B | BAF250B | 449 | c.1346del | p.Pro449Argfs*53 | Deletion_frameshift | de novo | 1 | 23929686 | |

| CSS | ARID1B | BAF250B | 464 | c.1389_1398del | p.Ala464Serfs*35 | Deletion_frameshift | de novo | 1 | 23815551 | |

| CSS | ARID1B | BAF250B | 467 | c.1392_1402del | p.Gln467Argfs*64 | Deletion_frameshift | de novo | 1 | 23815551 | |

| CSS | ARID1B | BAF250B | exon 1 | c.1542+1G>A | r.spl? | Substitution_splice site | de novo | 1 | 23929686 | |

| CSS | ARID1B | BAF250B | 560 | c.1678_1688del | p.Ile560Glyfs*89 | Deletion_frameshift | de novo | 1 | 22426308 | |

| CSS | ARID1B | BAF250B | 572 | c.1713del | p.Gly572Glufs*21 | Deletion_frameshift | de novo | 1 | 23815551 | |

| CSS | ARID1B | BAF250B | 635 | c.1903C>T | p.Gln635* | Substitution_nonsense | de novo | 1 | 22426308 | |

| CSS | ARID1B | BAF250B | 688 | c.2062del | p.Leu688Serfs*9 | Deletion_frameshift | de novo | 1 | 23815551 | |

| CSS | ARID1B | BAF250B | 715 | c.2144C>T | p.Pro715Leu | Substitution_missense | de novo | 1 | 22426308 | |

| CSS | ARID1B | BAF250B | exons 6–9 | exon 6–9del | p.0 | Deletion | de novo | 1 | 23929686 | |

| CSS | ARID1B | BAF250B | 867 | c.2598del | p.Tyr867Thrfs*47 | Deletion_frameshift | nc | 1 | 23929686 | |

| CSS | ARID1B | BAF250B | 935 | c.2803dup | p.Met935Asnfs*7 | Deletion_frameshift | nc | 1 | 23929686 | |

| CSS | ARID1B | BAF250B | 959 | c.2877del | p.Ser959Argfs*9 | Deletion_frameshift | de novo | 1 | 23929686 | |

| CSS | ARID1B | BAF250B | 964 | c.2891_2892insAC | p.Phe964Leufs*5 | Deletion_frameshift | de novo | 1 | 23815551 | |

| CSS | ARID1B | BAF250B | 1000 | c.2998del | p.Ala1000Argfs*5 | Deletion_frameshift | de novo | 1 | 23929686 | |

| CSS | ARID1B | BAF250B | exon 11 | c.3135+1G>C | r.spl? | Substitution_splice site | not in mother | 1 | 23929686 | |

| CSS | ARID1B | BAF250B | 1075 | c.3223C>T | p.Arg1075* | Substitution_nonsense | de novo | 1 | 22426309 | Santen et al. [31••] |

| CSS | ARID1B | BAF250B | 1102 | c.3304C>T | p.Arg1102* | Substitution_nonsense | de novo | 1 | 22426308 | |

| CSS | ARID1B | BAF250B | 1161 | c.3481G>T | p.Glu1161* | Substitution_nonsense | de novo | 1 | 23815551 | |

| CSS | ARID1B | BAF250B | 1283 | c.3846dup | p.Gly1283Trpfs*38 | Duplication_framshift | de novo | 1 | 23929686 | |

| CSS | ARID1B | BAF250B | 1366 | c.4098C>G | p.Tyr1366* | Substitution_nonsense | de novo | 1 | 23929686 | |

| CSS | ARID1B | BAF250B | 1337 | c.4009C<T | p. Arg1337* | Substitution_nonsense | nc | 1 | 23815551 | |

| CSS | ARID1B | BAF250B | 1489 | c.4448_4449ins14 | p.Pro1489Leufs*10 | Insertion_frameshift | nc | 1 | 23929686 | |

| CSS | ARID1B | BAF250B | 1540 | c.4620C>A | p.Tyr1540* | Substitution_nonsense | de novo | 1 | 23929686 | |

| CSS | ARID1B | BAF250B | 1541 | c.4619_4628del | p.Gln1541Argfs*35 | Deletion_frameshift | de novo | 1 | 22426309 | |

| CSS | ARID1B | BAF250B | 1607 | c.4820_ 4825delinsAGGCT | p.Thr1607Lysfs*7 | Deletion_frameshift | de novo | 1 | 23815551 | |

| CSS | ARID1B | BAF250B | 1609 | c.4821del | p.Pro1609Leufs*5 | Deletion_frameshift | de novo | 1 | 23815551 | |

| CSS | ARID1B | BAF250B | 1637 | c.4911_4915del | p.Trp1637Cysfs*6 | Deletion_frameshift | de novo | 1 | 23929686 | |

| CSS | ARID1B | BAF250B | 1637 | c.4911G>A | p.Trp1637* | Substitution_nonsense | de novo | 1 | 23815551 | |

| CSS | ARID1B | BAF250B | 1639 | c.4916_4917del | p.Val1639Aspfs*5 | Deletion_frameshift | de novo | 1 | 23815551 | |

| CSS | ARID1B | BAF250B | 1777 | c.5329A>T | p.Lys1777* | Substitution_nonsense | de novo | 1 | 22426309 | |

| CSS | ARID1B | BAF250B | 1798 | c.5394_5397del | p.Phe1798Leufs*52 | Deletion_frameshift | de novo | 1 | 23929686 | |

| CSS | ARID1B | BAF250B | 1875 | c.5623_ 5625delins- TGACGTCT | p.Ala1875* | Substitution_nonsense | nc | 1 | 23815551 | |

| CSS | ARID1B | BAF250B | 1878 | c.5632del G | p.Asp1878Metfs*96 | Deletion_frameshift | nc | 1 | 22426308 | |

| CSS | ARID1B | BAF250B | 1879 | c.5635delG | p.Asp1879Thrfs*95 | Deletion_frameshift | de novo | 1 | 23929686 | |

| CSS | ARID1B | BAF250B | 1990 | c.5968C>T | p.Arg1990* | Substitution_nonsense | Not in mother/nc/de novo | 3 | 23929686 | |

| CSS | ARID1B | BAF250B | 2013 | c.6038G>A | p.Trp2013* | Substitution_nonsense | de novo | 1 | 23929686 | |

| CSS | ARID1B | BAF250B | 2040 | c.6120C>G | p.Tyr2040* | Substitution_nonsense | nc | 1 | 23815551 | |

| CSS | ARID1B | BAF250B | 2078 | c.6233del | p.Pro2078Leufs*21 | Deletion_frameshift | de novo | 1 | 23929686 | |

| CSS | ARID1B | BAF250B | 2128 | c.6382C>T | p.Arg2128* | Substitution_nonsense | de novo | 1 | 23815551 | |

| CSS | ARID1B | BAF250B | 2172 | c.6516C>G | p.Tyr2172* | Substitution_nonsense | de novo | 1 | 23815551 | |

| CSS | ARID1B | BAF250B | 2234 | c.6700_6701del | p.Leu2234Glyfs*7 | Deletion_frameshift | nc | 1 | 23929686 | |

| CSS | ARID1B | BAF250B | Microdeletion | nc | 1 | 22426308 | ||||

| ID | ARID1B | BAF250B | 372 | p.Arg372Profs*163 | Frameshift | de novo | 1 | 22405089 | Hoyer et al. [33] | |

| ID | ARID1B | BAF250B | 1102 | p.Arg1102* | Substitution_nonsense | de novo | 1 | 22405089 | ||

| ID | ARID1B | BAF250B | 1108 | p.Lys1108Argfs*9 | Frameshift | de novo | 1 | 22405089 | ||

| ID | ARID1B | BAF250B | 1307 | p.Gln1307* | Substitution_nonsense | de novo | 1 | 22405089 | ||

| ID | ARID1B | BAF250B | 1338 | pArg1338Argfs*76 | Frameshift | de novo | 1 | 22405089 | ||

| ID | ARID1B | BAF250B | 1346 | p.Tyr1346* | Substitution_nonsense | de novo | 1 | 22405089 | ||

| ID | ARID1B | BAF250B | 2155 | p.Ser2155Leufs*33 | Frameshift | de novo | 1 | 22405089 | ||

| ID | SMARCB1 | BAF47 | 37 | c.110G>A | p.Arg37His | Substitution_missense | de novo | 1 | 22726846 | Kleefstra T. Am J Hum Genet. 2012 |

| ID/ASD/ACC/SSI | ARID1B | BAF250B | Breakpoint intron 5; chr6: 157,292,076– 157,292,079 | 3 bp deletion/insertion of 22 bps that match uniquely to a LINE sequence at chromosome 7 | Translocation t(1;6)(p31.1;q25.3), truncation | de novo | 1 | 21801163 | Halgren et al. [32] | |

| ID/ASD/ | ARID1B | BAF250B | Breakpoint | ARID1B-MRPP3 | Translocation t(6; 14)(q25.3; | de novo | 1 | 21042007 | Backx et al. [34] | |

| ACC/SSI | intron 5 | fusion and reciprocal fusion | q13.2), gene fusion | |||||||

| ID/ASD/ACC-ne/SSI | ARID1B | BAF250B | 0.2 Mb deletion_exons 4–8 | Deletion | de novo | 1 | 21801163 | |||

| ID/ASD/ACC-ne/SSI | ARID1B | BAF250B | 0.6 Mb deletion_exons 2–20 | Deletion | de novo | 1 | 21801163 | |||

| ID/ASD/SSI | ARID1B | BAF250B | 1.0 Mb deletion_exons 1–8 | Deletion | de novo | 1 | 21801163 | |||

| ID/ASD-ne/ACC-ne/SSI | ARID1B | BAF250B | 2.7 Mb deletion_5 RefSeq genes incl. ARID1B | Deletion | de novo | 1 | 21801163 | |||

| ID/ASD/ACC- partial/SSI | ARID1B | BAF250B | 4.6 Mb deletion_15 RefSeq genes incl. ARID1B, exons 1–7 | Deletion | de novo | 1 | 21801163 | |||

| ID/ACC- partial/SSI | ARID1B | BAF250B | 8.2 Mb deletion_33 RefSeq genes incl. ARID1B | Deletion | de novo | 1 | 21801163 | |||

| ID/ACC- hypoplasia/SSI | ARID1B | BAF250B | 14.5 Mb deletion_73 RefSeq genes incl. ARID1B | Deletion | de novo | 1 | 21801163 | |||

| NBS | SMARCA2 | Brm | 752 | c.2255G>C | p.Gly752Ala | Substitution_missense | de novo | 2 | 22366787 | Van Houdt et al. [28••] |

| NBS | SMARCA2 | Brm | 755 | c.2264A>G | p.Lys755Arg | Substitution_missense | de novo | 1 | 22366787 | |

| NBS | SMARCA2 | Brm | 756 | c.2267C>T | p.Thr756Ile | Substitution_missense | de novo | 1 | 22366787 | |

| NBS | SMARCA2 | Brm | 851 | c.2551G>C | p.Asp851His | Substitution_missense | de novo | 1 | 22366787 | |

| NBS | SMARCA2 | Brm | 852 | c.2556A>C | p.Glu852Asp | Substitution_missense | de novo | 1 | 22366787 | |

| NBS | SMARCA2 | Brm | 852 | c.2554G>A | p.Glu852Lys | Substitution_missense | de novo | 1 | 22366787 | |

| NBS | SMARCA2 | Brm | 854 | c.2560C>A c.2562C>A |

p.His854Leu | Substitution_missense | de novo | 1 | 22366787 | |

| NBS | SMARCA2 | Brm | 854 | c.2561A>G | p.His854Arg | Substitution_missense | de novo | 1 | 22366787 | |

| NBS | SMARCA2 | Brm | 855 | c.2563C>G | p.Arg855Gly | Substitution_missense | de novo | 1 | 22366787 | |

| NBS | SMARCA2 | Brm | 881 | c.2642G>T | p.Gly881Val | Substitution_missense | de novo | 1 | 22366787 | |

| NBS | SMARCA2 | Brm | 881 | c.2641G>C | p.Gly881Arg | Substitution_missense | de novo | 1 | 22366787 | |

| NBS | SMARCA2 | Brm | 883 | c.2648C>T | p.Pro883Leu | Substitution_missense | de novo | 3 | 22366787 | |

| NBS | SMARCA2 | Brm | 939 | c.2815C>T | p.His939Tyr | Substitution_missense | de novo | 1 | 22366787 | |

| NBS | SMARCA2 | Brm | 946 | c.2837T>C | p.Leu946Ser | Substitution_missense | de novo | 1 | 22366787 | |

| NBS | SMARCA2 | Brm | 946 | c.2838A>T | p.Leu946Phe | Substitution_missense | de novo | 1 | 22366787 | |

| NBS | SMARCA2 | Brm | 1105 | c.3313C>T | p.Arg1105Cys | Substitution_missense | de novo | 1 | 22366787 | |

| NBS | SMARCA2 | Brm | 1105 | c.3314G>C | p.Arg1105Pro | Substitution_missense | de novo | 1 | 22366787 | |

| NBS | SMARCA2 | Brm | 1132 | p.Gly1132Asp | Substitution_missense | de novo | 1 | 22822383 | Wolff et al. [29] | |

| NBS | SMARCA2 | Brm | 1135 | c.3404T>C | p.Leu1135Pro | Substitution_missense | de novo | 1 | 22366787 | |

| NBS | SMARCA2 | Brm | 1146 | c.3436A>C | p.Ser1146Arg | Substitution_missense | de novo | 1 | 22366787 | |

| NBS | SMARCA2 | Brm | 1158 | c.3473A>T | p.Asp1158Val | Substitution_missense | de novo | 1 | 22366787 | |

| NBS | SMARCA2 | Brm | 1159 | c.3476G>A | p.Arg1159Gln | Substitution_missense | de novo | 2 | 22366787 | |

| NBS | SMARCA2 | Brm | 1159 | c.3475C>G | p.Arg1159Gly | Substitution_missense | de novo | 1 | 22366787 | |

| NBS | SMARCA2 | Brm | 1159 | c.3476G>T | p.Arg1159Leu | Substitution_missense | de novo | 1 | 22366787 | |

| NBS | SMARCA2 | Brm | 1162 | c.3485G>A | p.Arg1162His | Substitution_missense | de novo | 2 | 22366787 | |

| NBS | SMARCA2 | Brm | 1188 | c.3562G>C | p.Ala1188Pro | Substitution_missense | de novo | 1 | 22366787 | |

| NBS | SMARCA2 | Brm | 1188 | p.Ala1188Glu | Substitution_missense | de novo | 1 | 22822383 | ||

| NBS | SMARCA2 | Brm | 1201 | c.3602C>T | p.Ala1201Val | Substitution_missense | de novo | 3 | 22366787 | |

| NBS | SMARCA2 | Brm | 1202 | c.3604G>T | p.Gly1202Cys | Substitution_missense | de novo | 1 | 22366787 | |

| NBS | SMARCA2 | Brm | 1205 | c.3614A>G | p.Asp1205Gly | Substitution_missense | de novo | 1 | 22366787 | |

| NBS | SMARCA2 | Brm | 1213 | c.3637C>T | p.Arg1213Trp | Substitution_missense | de novo | 1 | 22366787 | |

| NBS* | SMARCA2 | Brm | 852 | c.2554G>C | p.Glu852Gln | Substitution_missense | de novo | 1 | 23929686 | |

| NBS* | SMARCA2 | Brm | 939 | c.2815C>T | p.His939Tyr | Substitution_missense | de novo | 1 | 23929686 | |

| NBS* | SMARCA2 | Brm | 1098 | c.3293G>A | p.Gly1098Asp | Substitution_missense | nc | 1 | 23929686 | |

| NBS* | SMARCA2 | Brm | 1105 | c.3314G>A | p.Arg1105His | Substitution_missense | de novo | 1 | 23929686 | |

| SZ | SMARCA2 | Brm | Intron 12 | rs3763627 | SNP | de novo | 1 | 19363039 | Koga et al. [39] | |

| SZ | SMARCA2 | Brm | Intron 19 | rs3793490 | SNP | de novo | 1 | 19363039 | ||

| SZ | SMARCA2 | Brm | 1546 | rs2296212 | p.Asp1546Glu | SNP | de novo | 1 | 19363039 |

Abbreviations: ALS, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; ASD, autism spectrum disorder; CSS, Coffin–Siris syndrome; ID, intellectual disability; NBS, Nicolaides–Baraitser syndrome; SZ, schizophrenia; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; ACC, agenesis of corpus colosum; SSI, Severe speech impairment; ne, not examined; nc, In the inheritance column indicates that parental DNA was not available for testing.

Reclassified as NBS [44].

Infrequent mutation of BAF subunits in autism and schizophrenia

Exome sequencing studies of autism have found mutations in BAF250b, BAF180, BAF170, BAF155 and REST, the later of which controls BAF subunit switching (Table 1) [37••,38]. De novo mutations in BAF250b have been discovered in rare cases of human schizophrenia. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in BRM have been associated with schizophrenia [39]. The rarity of these mutations make it difficult to comment on their potential role in these diseases and additional studies will be necessary to determine if the infrequency with which they have been identified is due to genetic background or environmental interactions that determine the penetrance of these mutations. However, the finding that the defects in Brm-mutant and BAF53b-mutant mice appear to derive from abnormal postsynaptic components, such as dendritic spine structure and function, that ultimately leads to deficits in synaptic plasticity is consistent with defects found in humans with schizophrenia [16•,40].

Mutation of the BAF subunit CREST in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)

ALS, also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease, is a fatal adult-onset neurodegenerative disease characterized by loss of motor neurons [41]. Although ~10% of cases have a family history of ALS, the majority of cases are sporadic. Exome sequencing of ALS trios (ALS patient and both unaffected parents) found de novo mutations in the nBAF subunit CREST [42••]. CREST is a paralog of SS18, appears to have co-evolved with vertebrate tetrapod evolution and is required for activity dependent dendritic morphogenesis [4,15••]. The pathophysiological connection between the neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative roles of BAF complexes will be an area of future study that will benefit from sequencing BAF genes in patients with ALS and testing the resulting alleles in assays designed to test molecular mechanisms of development and disease.

BAF subunits as determinants of human phenotypic variation

One of the most exciting results of exome sequencing studies in human disease is that they will almost certainly give insight into human phenotypic variation resulting from mutations that produce only minor compromised function of a gene product. The genes that are dominant for a trait would be expected to contribute more to phenotypic variation, because only one allele needs to be mutated to produce a phenotype. Exome sequencing studies have found that mutations in BAF subunits are contributors to intellectual disability syndromes and sporadic intellectual disability. Analysis of the mutations that produce these syndromes strongly support a genetically dominant role, since alleles of BAF subunits predicted to produce no protein give rise to intellectual disability. These observations permit one to speculate that a series of weak alleles will be associated with variations in human intellectual ability. Needless to say this speculation will need much additional testing.

On the basis of the genetic dominance of BAF subunits in neural development and function we predict that some aspect of chromatin structure regulated by BAF complexes is rate limiting for one or more steps within the genetic circuitry of neural development. This is consistent with the instructive regulatory ability of BAF subunit switching in neural fate determination, because modulation of rate limiting steps within a circuitry or pathway will in general result in greater phenotypic change than modulation of the steps that are not rate limiting. Discovery of these rate limiting steps carried out by the cell type specific, combinatorially assembled BAF complexes will likely contribute to our understanding of human neural development and intellectual abilities.

Acknowledgments

We thank all members of the Crabtree Lab for engaging discussions on this topic and especially thank Dr. Andrew Yoo for critically reading the manuscript. GRC is funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

References and recommended reading

Papers of particular interest, published within the period of review, have been highlighted as:

• of special interest

•• of outstanding interest

- 1•.Olave I, Wang W, Xue Y, Kuo A, Crabtree GR. Identification of a polymorphic, neuron-specific chromatin remodeling complex. Genes Dev. 2002;16:2509–2517. doi: 10.1101/gad.992102. First identification of a neural specific chromatin remodeling mechanism. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu JI, Lessard J, Olave IA, Qiu Z, Ghosh A, Graef IA, Crabtree GR. Regulation of dendritic development by neuron-specific chromatin remodeling complexes. Neuron. 2007;56:94–108. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3••.Lessard J, Wu JI, Ranish JA, Wan M, Winslow MM, Staahl BT, Wu H, Aebersold R, Graef IA, Crabtree GR. An essential switch in subunit composition of a chromatin remodeling complex during neural development. Neuron. 2007;55:201–215. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.06.019. The authors searched for neural specific chromatin remodeling mechanisms and found that both neurons and neural stem cells had destinctive chromatin regulators. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Staahl B, Tang J, Wu W, Sun A, Gitler A, Yoo A, Crabtree G. Kinetic analysis of npBAF to nBAF switching reveals exchange of SS18 with CREST and integration with neural developmental pathways. Journal of Neuroscience. 2013;33:10348–10361. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1258-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hargreaves DC, Crabtree G. ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling: genetics, genomics and mechanisms. Cell Res. 2011;21:396–420. doi: 10.1038/cr.2011.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6•.Ho L, Crabtree GR. Chromatin remodelling during development. Nature. 2010;463:474–484. doi: 10.1038/nature08911. Excellent review on the evolution of ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling complexes and their function in multicellular animals. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7•.Wang W, Cote J, Xue Y, Zhou S, Khavari PA, Biggar SR, Muchardt C, Kalpana GV, Goff SP, Yaniv M, et al. Purification and biochemical heterogeneity of the mammalian SWI–SNF complex. EMBO J. 1996;15:5370–5382. This and the paper below were the first realization that what had been thought of as a monomorphic SWI/SNF complex was in fact a heterogenous collection of combinatorially assembled complexes. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang W, Xue Y, Zhou S, Kuo A, Cairns BR, Crabtree GR. Diversity and specialization of mammalian SWI/SNF complexes. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2117–2130. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.17.2117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khavari PA, Peterson CL, Tamkun JW, Mendel DB, Crabtree GR. BRG1 contains a conserved domain of the SWI2/SNF2 family necessary for normal mitotic growth and transcription. Nature. 1993;366:170–174. doi: 10.1038/366170a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10•.Zhao K, Wang W, Rando OJ, Xue Y, Swiderek K, Kuo A, Crabtree GR. Rapid and phosphoinositol-dependent binding of the SWI/SNF-like BAF complex to chromatin after T lymphocyte receptor signaling. Cell. 1998;95:625–636. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81633-5. The authors discovered that β-actin is a subunit of mammalian BAF complexes. Actin however is not a subunit of the yeast SWI/SNF complex. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11•.Ho L, Ronan JL, Wu J, Staahl BT, Chen L, Kuo A, Lessard J, Nesvizhskii AI, Ranish J, Crabtree GR. An embryonic stem cell chromatin remodeling complex, esBAF, is essential for embryonic stem cell self-renewal and pluripotency. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:5181–5186. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812889106. The authors purified and sequenced the subunits of BAF complexes in ES cells and found that they had a specific subunit composition. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kadoch C, Crabtree G. Reversible disruption of mSWI/SNF (BAF) complexes by the SS18-SSX oncogenic fusion in synovial sarcoma. Cell. 2013;153:71–85. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ho L, Jothi R, Ronan JL, Cui K, Zhao K, Crabtree GR. An embryonic stem cell chromatin remodeling complex, esBAF, is an essential component of the core pluripotency transcriptional network. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:5187–5191. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812888106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14•.Bultman S, Gebuhr T, Yee D, La Mantia C, Nicholson J, Gilliam A, Randazzo F, Metzger D, Chambon P, Crabtree G, et al. A Brg1 null mutation in the mouse reveals functional differences among mammalian SWI/SNF complexes. Mol Cell. 2000;6:1287–1295. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00127-1. The authors produced mice with a null allele of Brg1 and found that about 15% of heterozygous mice had defects in neural tube closure, indicating a genetically dominant mode of action consistent with later exome sequencing studies in humans. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15••.Aizawa H, Hu SC, Bobb K, Balakrishnan K, Ince G, Gurevich I, Cowan M, Ghosh A. Dendrite development regulated by CREST, a calcium-regulated transcriptional activator. Science. 2004;303:197–202. doi: 10.1126/science.1089845. This was the first identification of CREST in a screen for genes that could mediate a response to depolarization induced Ca2++. From studies by Staahl et al. [4] (submitted we now know that CREST is a dedicated subunit of nBAF complexes and is essential for the function of the complex) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16•.Vogel-Ciernia A, Matheos DP, Barrett RM, Kramár EA, Azzawi S, Chen Y, Magnan CN, Zeller M, Sylvain A, Haettig J, et al. The neuron-specific chromatin regulatory subunit BAF53b is necessary for synaptic plasticity and memory. Nat Neurosci. 2013;5:552–561. doi: 10.1038/nn.3359. The authors found that mice heterozygous for BAF53b have defects not only in dendritic morphogenesis but also postsynaptic structure and function that leads to deficits in synaptic plasticity. This study likely helps explain the frequency with which BAF subunit mutations produce intellectual disability. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17••.Parrish JZ, Kim MD, Jan LY, Jan YN. Genome-wide analyses identify transcription factors required for proper morphogenesis of Drosophila sensory neuron dendrites. Genes Dev. 2006;20:820–835. doi: 10.1101/gad.1391006. The authors conducted an RNAi screen for genes required for dendritic morphogenesis in the fly and found several BAF subunits. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18•.Tea JS, Luo L. The chromatin remodeling factor Bap55 functions through the TIP60 complex to regulate olfactory projection neuron dendrite targeting. Neural Dev. 2011;6:5. doi: 10.1186/1749-8104-6-5. The authors conducted a couragous screen for genes that cause perfect retargeting of central nervous system olfactory projection neuron dendrites from one glomerulus to another. They found that only BAP55 could induce this phenotype, which was rescued by human BAF53b nearly completely. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19••.Yoo AS, Staahl BT, Chen L, Crabtree GR. MicroRNA-mediated switching of chromatin-remodelling complexes in neural development. Nature. 2009;460:642–646. doi: 10.1038/nature08139. The authors defined the genetic circuitry underlying the epigenetic switch in chromatin regulatory complexes during neural development. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ebert M, Sharp P. Roles for MicroRNAs in conferring robustness to biological processes. Cell. 2012;149:515–524. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Makeyev EV, Zhang J, Carrasco MA, Maniatis T. The MicroRNA miR-124 promotes neuronal differentiation by triggering brain-specific alternative pre-mRNA splicing. Mol Cell. 2007;27 :435–448. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Conaco C, Otto S, Han JJ, Mandel G. Reciprocal actions of REST and a microRNA promote neuronal identity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:2422–2427. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511041103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23••.Yoo AS, Sun AX, Li L, Shcheglovitov A, Portmann T, Li Y, Lee-Messer C, Dolmetsch RE, Tsien RW, Crabtree GR. MicroRNA-mediated conversion of human fibroblasts to neurons. Nature. 2011;476:228–231. doi: 10.1038/nature10323. The authors demonstrated that recapitulation of the microRNA-chromatin switch defined in Yoo, Staahl et al. could effectively reprogram fibrolasts to neurons. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126:663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25••.Vierbuchen T, Ostermeier A, Pang ZP, Kokubu Y, Sudhof TC, Wernig M. Direct conversion of fibroblasts to functional neurons by defined factors. Nature. 2010;463:1035–1041. doi: 10.1038/nature08797. This paper defined the first reprogramming of mouse fibroblasts to neurons. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pang ZP, Yang N, Vierbuchen T, Ostermeier A, Fuentes DR, Yang TQ, Citri A, Sebastiano V, Marro S, Sudhof TC, et al. Induction of human neuronal cells by defined transcription factors. Nature. 2011;476:220–223. doi: 10.1038/nature10202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sun AX, Crabtree G, Yoo A. MicroRNAs: regulators of neuronal fate. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2013;2:215–221. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2012.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28••.Van Houdt JK, Nowakowska BA, Sousa SB, van Schaik BD, Seuntjens E, Avonce N, Sifrim A, Abdul-Rahman OA, van den Boogaard MJ, Bottani A, et al. Heterozygous missense mutations in SMARCA2 cause Nicolaides–Baraitser syndrome. Nat Genet. 2012;44:445–449. doi: 10.1038/ng.1105. Another landmark exome sequecing paper that identified BRM (BAF190) as the cause of this syndrome characterized by severe language impairment and intellectual disability. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wolff D, Endele S, Azzarello-Burri S, Hoyer J, Zweier M, Schanze I, Schmitt B, Rauch A, Reis A, Zweier C. In-frame deletion and missense mutations of the C-terminal helicase domain of SMARCA2 in three patients with Nicolaides–Baraitser syndrome. Mol Syndromol. 2012;2:237–244. doi: 10.1159/000337323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30••.Tsurusaki Y, Okamoto N, Ohashi H, Kosho T, Imai Y, Hibi-Ko Y, Kaname T, Naritomi K, Kawame H, Wakui K, et al. Mutations affecting components of the SWI/SNF complex cause Coffin–Siris syndrome. Nat Genet. 2012;44:376–378. doi: 10.1038/ng.2219. A landmark paper identifying 5 subunits of nBAF and npBAF complexes as mutated in Coffin–Siris syndrome. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31••.Santen GW, Aten E, Sun Y, Almomani R, Gilissen C, Nielsen M, Kant SG, Snoeck IN, Peeters EA, Hilhorst-Hofstee Y, et al. Mutations in SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex gene ARID1B cause Coffin–Siris syndrome. Nat Genet. 2012;44:379–380. doi: 10.1038/ng.2217. A landmark paper identifying BAF250b mutations as the cause of Coffin Siris syndrome. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32•.Halgren C, Kjaergaard S, Bak M, Hansen C, El-Schich Z, Anderson C, Henriksen K, Hjalgrim H, Kirchhoff M, Bijlsma E, et al. Corpus callosum abnormalities, intellectual disability, speech impairment, and autism in patients with haploinsufficiency of ARID1B. Clin Genet. 2011;82:248–255. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2011.01755.x. Identified BAF250b as a commonly deleted gene in patients with a range of intellectual disability. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hoyer J, Ekici AB, Endele S, Popp B, Zweier C, Wiesener A, Wohlleber E, Dufke A, Rossier E, Petsch C, et al. Haploinsufficiency of ARID1B, a member of the SWI/SNF-A chromatin-remodeling complex, is a frequent cause of intellectual disability. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;90:565–572. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Backx L, Seuntjens E, Devriendt K, Vermeesch J, Van Esch H. A balanced translocation t(6;14)(q25.3;q13. 2) leading to reciprocal fusion transcripts in a patient with intellectual disability and agenesis of corpus callosum. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2011;132:135–143. doi: 10.1159/000321577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Santen G, Kriek M, van Attikum H. SWI/SNF complex in disorder: SWItching from malignancies to intellectual disability. Epigenetics. 2012;7:1219–1224. doi: 10.4161/epi.22299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim JK, Huh SO, Choi H, Lee KS, Shin D, Lee C, Nam JS, Kim H, Chung H, Lee HW, et al. Srg3, a mouse homolog of yeast SWI3, is essential for early embryogenesis and involved in brain development. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:7787–7795. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.22.7787-7795.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37••.O’Roak BJ, Vives L, Girirajan S, Karakoc E, Krumm N, Coe BP, Levy R, Ko A, Lee C, Smith JD, et al. Sporadic autism exomes reveal a highly interconnected protein network of de novo mutations. Nature. 2012;485:246–250. doi: 10.1038/nature10989. The authors identified components of the npBAF to nBAF switch as mutated in autism. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Neale BM, Kou Y, Liu L, Ma’ayan A, Samocha KE, Sabo A, Lin CF, Stevens C, Wang LS, Makarov V, et al. Patterns and rates of exonic de novo mutations in autism spectrum disorders. Nature. 2012;485:242–245. doi: 10.1038/nature11011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Koga M, Ishiguro H, Yazaki S, Horiuchi Y, Arai M, Niizato K, Iritani S, Itokawa M, Inada T, Iwata N, et al. Involvement of SMARCA2/BRM in the SWI/SNF chromatin-remodeling complex in schizophrenia. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:2483–2494. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Loe-Mie Y, Lepagnol-Bestel A, Maussion G, Doron-Faigenboim A, Imbeaud S, Delacroix H, Aggerbeck L, Pupko T, Gorwood P, Simonneau M, et al. SMARCA2 and other genome-wide supported schizophrenia-associated genes: regulation by REST/NRSF, network organization and primate-specific evolution. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:2841–2857. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Andersen PM, Al-Chalabi A. Clinical genetics of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: what do we really know? Nat Rev Neurol. 2011;7 :603–615. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2011.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chesi AS, Staahl BT, Couthouis J, Fasolino M, Raphael AR, Polak M, Kelly C, Maragakis NJ, Crabtree GR, Glass JD, Gitler AD. De novo mutations in sporadic ALS trios. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16:851–855. doi: 10.1038/nn.3412. First systematic analysis of ALS trios (ALS patient and both unaffected parents. For the first time the authors do a systematic analysis of exome sequencing of trios consisting of subjects with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and their unaffected parents to find de novo variants in 25 genes, one of which is the chromatin regulator CREST (SS18L1).). ••. First study to identify a BAF subunit in a neurodegenerative disease. Identified two mutant CREST alleles in ALS patients and functionally characterized them to have a genetically dominant dendritic outgrowth phenotype. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Oma Y, Nishimori K, Harata M. The brain-specific actin-related protein ArpN alpha interacts with the transcriptional co-repressor CtBP. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;301:521–528. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)03073-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Santen G, Aten E, Vulto-Van Silfhout A, Pottinger C, Van Bon B, Van Minderhout I, Snowdowne R, Van Der Lans C, Boogaard M, Linssen M, et al. Coffin-Siris syndrome and the BAF complex: genotype-phenotype study in 63 patients. Human Mutation. 2013 doi: 10.1002/humu.22394. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tsurusaki Y, Okamoto N, Ohashi H, Mizuno S, Matsumoto N, Makita Y, Fukuda M, Isidor B, Perrier J, Aggarwal S, et al. Coffin-Siris syndrome is a SWI/SNF complex disorder. Clinical genetics. 2013 doi: 10.1111/cge.12225. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nord A, Roeb W, Dickel D, Walsh T, Kusenda M, O’connor K, Malhotra D, Mccarthy S, Stray S, Taylor S, et al. Reduced transcript expression of genes affected by inherited and de novo CNVs in autism. European Journal of Human Genetics. 2011;19:727–731. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2011.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]