Abstract

The authors created two tools to achieve the goals of providing physicians with a way to review alternative diagnoses and improving access to relevant evidence-based library resources without disrupting established workflows. The “diagnostic decision support tool” lifted terms from standard, coded fields in the electronic health record and sent them to Isabel, which produced a list of possible diagnoses. The physicians chose their diagnoses and were presented with the “knowledge page,” a collection of evidence-based library resources. Each resource was automatically populated with search results based on the chosen diagnosis. Physicians responded positively to the “knowledge page.”

INTRODUCTION

Incorporating evidence-based information into patient care requires making the right information available at the right time 1. The right time may be during the diagnostic process, while providing care at the patient's bedside, or at any other point on the examination and treatment continuum. Physicians who are already under pressure to see more patients in less time are less likely to search for information to inform their decisions when the search interrupts their workflow 2. One method to remedy this situation is to provide a clinical decision support (CDS) system with links to relevant evidence-based information resources that can be accessed directly from the electronic health record (EHR) through the use of infobuttons. “Studies on Infobuttons have shown that clinicians find them useful and that information specific to a particular patient's situation is more useful than general information” 3. CDS systems are “active knowledge systems which use two or more items of patient data to generate case-specific advice” 4. Infobuttons are defined as “links between clinical information systems and online knowledge resources” 5. Integrating CDS resources into existing clinical workflows via infobuttons has the potential to reduce diagnostic or treatment errors by providing evidence-based information specific to the clinical scenario at hand.

This report describes a pilot project to integrate a CDS tool that includes context-sensitive, evidence-based information resources in an EHR that supports the emergency unit (EU) of a 250-bed pediatric teaching hospital. As in previous efforts reported by libraries to embed CDS tools into the EHR, the authors focused on providing library content at the point of care 6, 7. The project built on previous work by adding a way for patient data specific to an emergency room visit to be pulled directly from the EHR by clicking an infobutton, resulting in a list of possible diagnoses from which a search for related evidence-based information is automatically generated. Past efforts did not include a list of possible diagnoses, and searches had to be manually entered by the user. The goals of the project reported here were to (1) provide a straightforward mechanism for physicians to review alternative diagnoses prior to finalizing a treatment plan and (2) dramatically improve the ease of access to relevant evidence-based information resources without disrupting established workflows.

DEVELOPMENT OF A SPECIALIZED CLINICAL DECISION SUPPORT TOOL

A new chief medical information officer at the hospital wanted to integrate a CDS tool into the EU's EHR and saw the library as an essential component in this project. He convened a committee comprising two clinical librarians, the medical library director and associate director; the information systems coordinator (ISC) who handles the technical aspects of the EHR for the emergency medicine department; and two physicians specializing in informatics to plan the creation and integration of a CDS into the emergency medicine department EHR. The main issues considered were: (1) locating a vendor who was prepared to work with Wellsoft, the EHR software in use at the time; (2) pulling contextual data from the patient record; (3) providing a mechanism for physicians to review alternative diagnoses; (4) providing seamless access to context-based, evidence-based information resources without interrupting work flow; (5) promoting the tool to users and educating them on how to use it; and (6) measuring the success of the tool.

EBSCO, UpToDate, and Isabel were approached as potential partners in our project. Isabel was selected based on their prior experience and willingness to work with Wellsoft. Isabel is a diagnosis checklist tool to help physicians broaden their differential diagnoses and recognize a disease at the point of care 8.

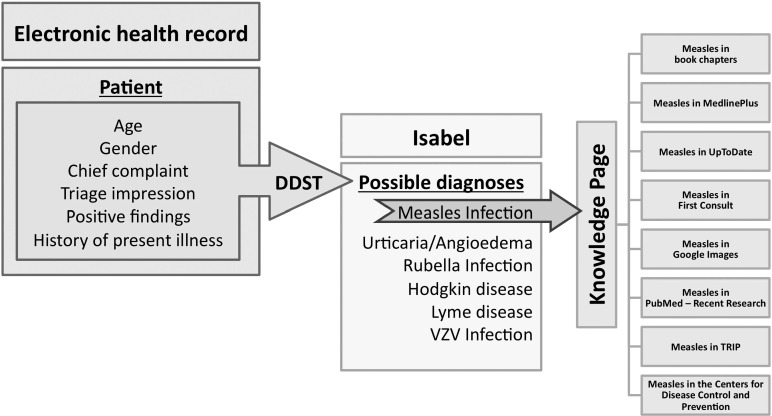

Working with Isabel and Wellsoft, the ISC created and integrated a diagnostic decision support tool (DDST) into the EHR. This tool works by lifting terms from standard coded fields in the record for age, gender, chief complaint, triage impression, positive findings, and history of present illnesses and sending the terms to Isabel, which then runs a search and produces a result of possible diagnoses (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Diagnostic decision support tool (DDST)

The DDST passes patient information to Isabel. Isabel produces a list of possible diagnoses based on the patient information. When the user chooses one of those diagnoses, the keyword that represents that diagnosis is passed to each resource in the knowledge page via an embedded uniform resource locator.

Isabel provided a basic web-based knowledge page (KP) for each diagnosis that initially offered textbook chapters, an option for a broad search of PubMed, and a link to the medical library's website. Isabel sent this KP to the librarians on the team and requested feedback. Based on both librarians' extensive training and experience in the clinical application of evidence-based information and facilitation of access to library resources, the medical librarians requested the addition of resources including clinical summaries from UpToDate and First Consult, articles ranked by level of evidence via TRIP, images from Google Images, public health information via the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and consumer health information from MedlinePlus. The librarians did not consider a general link to the library's website particularly useful and requested that it be replaced with a personalized email link to a librarian. Additionally, the PubMed search was modified to focus on the most recently published research and case studies. All of these changes were made prior to the pilot launch.

When physicians are in a patient's record in the EHR, they see a “DDST” tab. When they choose that tab, a window comes up with the list of possible diagnoses from Isabel (Figure 1). At that point, they can choose one of the listed diagnoses, and clicking on a diagnosis launches the KP. The word or phrase describing the diagnosis from Isabel is embedded into uniform resource locators (URLs) that are used to run searches in all resources in the KP at the same time. Physicians see a new page that lists each resource in a column on the left of the page, and the full result from whichever resource they click on is in a larger column to the right that fills the rest of the page. From there, they can choose which search result or resource they want to look at more closely, and that result fills the right-hand column.

IMPLEMENTATION

The pilot was launched in October 2011 and ran until April 2012. To introduce and evaluate the new tool, presentations to members of the EU division, including attending physicians and fellows, were held before, during, and after the pilot. These sessions were scheduled with the division secretary as part of regularly scheduled weekly EU meetings. They consisted of demonstrating the DDST and KP via a PowerPoint presentation that showed click-by-click screenshots of the user experience from launching Isabel from the EHR to each individual resource listed in the KP. Participants were then asked for feedback.

In addition, with support from the chief residents, one of the authors (Yaeger) approached attending physicians and residents in the EU physician workspace to demonstrate the DDST and KP at the point of care. Reference cards created by the vendor and librarian business cards were handed out. Step-by-step instructions on how to use the DDST and KP were presented at meetings of the Emergency Preparedness Workgroup, EU division, Education Committee, and a resident noon conference.

Overall, 25 visits were made to the EU, 5 presentations were made, and 3 focus groups were conducted. A total of 150 physicians out of 200 were reached directly.

MEASUREMENT

A three-question evaluation survey about the effect of Isabel's list of potential diagnoses on diagnosis, consultation, and treatment was integrated to the right of the list of diagnoses. Survey results and access were recorded by the ISC. The turnaround time from initiation of the DDST from the EHR to the presentation of possible diagnoses by Isabel was determined. The number of times that physicians initiated the DDST and the number of times that the DDST was used with unique patients were also tracked. The number of times that the KP was accessed was not tracked. Field observation notes and physician comments were recorded by the librarian (Yaeger) during presentations, EU one-on-one education visits, and focus groups.

RESULTS

The DDST was initiated 167 times for 125 unique patients out of a potential 34,000 patients from October 2011 through April 2012.

Two users responded to the survey. Both responders confirmed that Isabel's list of potential diagnoses influenced their differential diagnoses.

The 7 physicians who attended the focus groups responded negatively to Isabel's list of potential diagnoses but were interested in and excited about the KP. They strongly suggested the DDST be redesigned to incorporate the diagnosis from the EHR and send it directly to the KP, bypassing Isabel altogether.

Several users outside the focus groups also expressed keen interest in the KP and explained that while they were familiar with most of the resources, they rarely remembered to use them on their own. Additionally, for most of them this was their first exposure to TRIP and MedlinePlus.

The turnaround time from initiation of the DDST to the presentation of possible diagnoses by Isabel was 24.5 seconds (+/−3). Lack of interest in moving beyond the list of possible diagnoses to the KP and annoyance at the turnaround time from the DDST to Isabel were observed.

DISCUSSION

The physicians in the focus groups explained that they did not need assistance via Isabel to make correct diagnoses. They liked the KP because search results were automatically generated and included resources they did not normally think to use.

Users expressed lack of interest in choosing a diagnosis from the list of possible diagnoses aggregated by Isabel. Making that choice would have taken them to the automatically generated evidence-based information search results in the KP, based on their chosen diagnoses. The physicians were reluctant to choose a diagnosis from the list because the physician's own diagnosis was often not listed or the suggested diagnoses were too broad. For example, in a case where the patient had a broken elbow joint, the possible diagnosis that Isabel offered was “broken arm.” A possible reason for missing and overly broad diagnoses was that the list was made available at a point in the examination when the physician had only partially filled out the patient record. The accuracy of the differentials can only be as good as the data the DDST pulls and sends to Isabel. The 24.5 seconds (+/−3) wait time for the DDST to run and then for Isabel to produce results was perceived as time wasted, and it deterred use.

The low response rate to the survey was likely because of physical and temporal placement. Physically, it appeared on the far-right bottom of the possible diagnoses page in Isabel. When looking at that page, users were focused on the list of diagnoses, so many overlooked the survey. Temporally, the survey appeared before users had a chance to access the KP.

CONCLUSION

Integrating evidence-based information resources into the point-of-care workflow requires constant effort and time. Physician feedback received as part of this project supports making library resources accessible, mobile, and usable in the clinical environment. By conducting this pilot, the authors better understand the challenges involved in integrating a CDS tool into the EHR and physician workflow in the EU. The goal to provide a straightforward mechanism for physicians to review alternative diagnoses prior to finalizing a treatment plan was achieved in part. The authors were successful in creating and integrating the DDST and connecting it to the differential diagnostic tool, Isabel. However, to make the DDST more effective, the tool will need to be redesigned to pull more patient data and produce results faster.

In focus groups and during the real time demonstrations in the EU, physicians requested that their diagnoses be pulled from the EHR and passed directly to the KP. Unfortunately, their diagnoses were often in the notes section of the EHR, which did not have standard coded fields. After the pilot, the authors added a dialog box to the EHR where the physician can enter search terms that are passed via embedded URLs to each resource in the KP.

Evidence from this project suggests that physicians value one click access to search results that are automatically populated based on the diagnosis in multiple evidence-based library resources via the KP. Bernard Becker Medical Library staff developed an independent KP that can be readily integrated into other EHRs in use throughout the medical center. The authors plan to continue this work, testing the independent KP with additional EHRs, to provide physicians with what they want: one click access to evidence-based resources.

Footnotes

Based on a presentation at MLA '12, the 112th Annual Meeting of the Medical Library Association; Seattle, WA.

REFERENCES

- 1.Karsh BT. Clinical practice improvement and redesign: how change in workflow can be supported by clinical decision support. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grumbach K, Bodenheimer T. Can health care teams improve primary care practice. JAMA. 2004 Mar 10;291(10):1246–51. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.10.1246. Epub 2004/03/11. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.291.10.1246. PubMed PMID: 15010447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alpi KM, Burnett HA, Bryant SJ, Anderson KM. Connecting knowledge resources to the veterinary electronic health record: opportunities for learning at point of care. J Vet Med Educ. 2011;38(2):110–22. doi: 10.3138/jvme.38.2.110. Epub 2011/10/26. DOI:http://dx.doi.org/10.3138/jvme.38.2.110. PubMed PMID: 22023919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wyatt J. Computer-based knowledge systems. Lancet. 1991 Dec 7;338(8780):1431–6. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)92731-g. Epub 1991/12/07. PubMed PMID: 1683428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cimino JJ. An integrated approach to computer-based decision support at the point of care. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 2007;118:273–88. Epub 2008/06/06. PubMed PMID: 18528510. PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC1863602. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Epstein BA, Tannery NH, Wessel CB, Yarger F, LaDue J, Fiorillo AB. Development of a clinical information tool for the electronic medical record: a case study. J Med Lib Assoc. 2010 Jul;98(3):223–7. doi: 10.3163/1536-5050.98.3.010. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3163/1536-5050.98.3.010. PubMed PMID: 20648256;. PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC2900999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Welton NJ. The University of Washington electronic medical record experience. J Med Lib Assoc. 2010 Jul;98(3):217–9. doi: 10.3163/1536-5050.98.3.008. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3163/1536-5050.98.3.008. PubMed PMID: 20648254. PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC2901013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Healthcare I. Isabel 2013 [Internet] [cited 2013]. < http://www.isabelhealthcare.com>. [Google Scholar]