Abstract

Mutations in the ATP2C1 gene encoding Ca2+/Mn2+ ATPase SPCA1 cause Hailey-Hailey disease (HHD, OMIM 16960). HHD is characterized by epidermal acantholysis. We attempted to model HHD using normal keratinocytes in which the SPCA1 mRNA was down-regulated with the small inhibitory RNA (siRNA) method. SiRNA inhibition significantly down-regulated the SPCA1 mRNA, as demonstrated by qPCR, and decreased the SPCA1 protein beyond detectable level, as shown by western analysis. The expression of selected desmosomal, adherens and tight junction (TJ) proteins was then studied in the SPCA1-deficient and control keratinocytes cultured in low (0.06 mM) or high (1.2 mM) calcium concentration. The mRNA and protein levels of most TJ components were up-regulated in non-treated control keratinocyte cultures upon switch from low to high calcium concentration. In contrast, SPCA1-deficient keratinocytes displayed high levels of TJ proteins claudin 1 and 4 even in low calcium. ZO-1 did not however follow similar expression patterns. Protein levels of occludin, betacatenin, E-cadherin, desmoplakin, desmogleins 1-3, desmocollin 2/3 and plakoglobin did not show marked changes in SPCA1 deficient keratinocytes. Indirect immunofluorescence labeling revealed delayed translocation of desmoplakin and desmoglein 3 in desmosomes, and increased intracellular pools of TJ and desmosomal components in SPCA1 inhibited keratinocytes. The results show that SPCA1 regulates the levels of claudins 1 and 4, but does not affect desmosomal protein levels, indicating that TJ proteins are differently regulated. The results also suggest a potential role for claudins in HHD.

Keywords: Hailey-Hailey disease, tight junction, keratinocyte, ATP2C1, SPCA1

Introduction

Hailey-Hailey disease (HHD, OMIM 16960) is an autosomal dominant blistering skin disease with an estimated incidence of 1:40,000. HHD is characterized by superficial blistering of the epidermis, resulting in erosions mostly in flexural areas (1,2). The severity of the disease varies between families and also with individuals in the same family.

HHD is caused by mutations in the ATP2C1 gene, which encodes the Golgi secretory pathway Ca2+/Mn2+ ATPase protein 1 (hSPCA1) (3,4). HHD mutations lead to haploinsufficiency due to decreased amount of functional SPCA1 Ca2+/Mn2+ pump in keratinocytes (4). This leads to defects in the maintenance of intracellular calcium concentration and manganese balance (4,5). Because of the deficient Golgi Ca2+ pump, the restoration of the Golgi Ca2+ stores is slower than in normal keratinocytes (6,7). HHD keratinocytes are also less sensitive to the elevated extracellular Ca2+ levels (4). Normal function of SPCA1 contributes to the transportation of cellular adhesive proteins via secretory pathways, and it has been suggested that the defects in SPCA1 may lead to the symptoms of HHD by affecting the intracellular transportation (8–10). The most prominent epidermal histological feature of HHD is suprabasal acantholysis, which seems to result from disintegration of intercellular adhering junctions. (11–13).

Different factors have been suggested to contribute to acantholysis. These include plasminogen activation, faulty action or reduced intercellular interactions of junction proteins or activation of certain miRNAs (11,12,14). Although the primary abnormalities in calcium metabolism in HHD are known, the mechanisms how SPCA1 regulates junctional integrity or the sequence of events leading to disruption of adhering junctions are not understood to date, and the pathoetiology of the disease thus appears increasingly complex.

Desmosomes and the classical adherens junctions are the adhering junction types of the epidermis. Desmosomes link the cytokeratin filament network to the plasma membrane and interconnect neighboring cells, thus maintaining intercellular adhesive strength and integrity of the epidermis. The major structural components of desmosomes include the intercellular proteins plakoglobin and desmoplakin, and the transmembrane cadherins desmogleins and desmocollins. Desmosome formation is calcium-dependent and it also depends on the presence of adherens junctions. On the other hand, the maturation of adherens junctions has been shown to depend on functional desmosomes (15). Tight junctions (TJs) are intercellular junctions, which contribute to the epidermal barrier function of the epidermis, especially the diffusion of water from inside out (16–18). In normal human epidermis, TJs are located in the granular layer (19,20). TJ components include the transmembrane proteins occludin, members of the claudin family, and intracellular linking molecules such as zonula occludens protein 1 (ZO-1). Our previous studies have shown that abnormal epidermal differentiation is associated with disturbances in distribution of TJ proteins (21). The localization of TJ proteins claudins 1 and 4, ZO-1 and occludin in HHD perilesional skin is similar to that described in normal skin, but in acantholytic cells the TJ proteins follow different dynamics compared to the desmosomal proteins (22). Specifically, desmosomal components are internalized while TJ components claudin-1 and ZO-1 seem to remain in the original junction sites although cells lose contacts.

Cell culture models provide an opportunity to study intercellular junctions in conditions where cells are not influenced by disturbing environmental factors, which may apply in vivo. Obtaining keratinocytes from HHD patients for culture is however challenging since the disease is rare. In this study, siRNAs were utilized to model HHD by down-regulating the expression of the ATP2C1 gene in normal keratinocytes. This approach resulted in a significant reduction of the SPCA1 mRNA and protein. Expression of selected desmosomal, adherens and TJ proteins was subsequently investigated at the mRNA and protein levels. The results showed that claudin 1 and 4 were regulated by SPCA1. Surprisingly, the synthesis of desmosomal proteins was not affected by SPCA1 inhibition while the translocation of desmoplakin and desmoglein 3 at the cell junctions was delayed.

Methods

Keratinocyte cultures

Normal keratinocytes were obtained from skin samples of patients undergoing plastic surgery at Turku University Central Hospital. The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Southwest Finland Hospital District and the Department of Surgery, Turku University Hospital. The patients gave their written consent before the surgery. The culturing method was based on a method previously described (23). Keratinocytes were cultured in Keratinocyte Growth Medium (KGM-2) (PromoCell GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany) supplemented with SupplementMix and 0.06 mM CaCl2 (both from PromoCell) and penicillin-streptomycin mixture (Gibco, Paisley, UK). The experiments were conducted either in lowcalcium condition (0.06 mM) or in high calcium condition (1.2 or 1.8 mM CaCl2).

siRNA Transfection

Small inhibitory RNAs (siRNAs) 50 μM [0030] SASI_Hs01_00044646 (sense 5′ GUGAAUUACCAGUCAGUGA, antisense 5′UCACUGACUGGUAAUUCAC) = siRNA 46, [0090]SASI_Hs01_00044645 (sense 5′ GGUAUAAUAGGAAUCAUCA, antisense 5′ UGAUGAUUCCUAUUAUACC)=siRNA 45 were purchased from Sigma company (St. Louis, MO, USA). Negative control siRNA (catalog no 1027310) was purchased from Qiagen (Hilden, Germany). Keratinocytes of 4–5 passage were seeded at a density of 1.4 to 1.7 × 104 cm2 and grown overnight in the KGM-2 containing Supplement Mix with low calcium concentration. The cells were transfected using SiLentFect Lipid reagent (cat no 170-3360 Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The final siRNA concentration was 75 nM and the transfection was allowed to continue for six hours, after which the transfection medium was removed and replaced by KGM-2 with low or high calcium concentration. The cells were harvested for western analysis, RNA isolation or immunofluorescence labelling at 72 hours post-transfection. All experiments were repeated at least three times using cells originating from three different patients.

Quantitive PCR

Quantitive PCR (qPCR) was used to analyse the effects of knock-down on mRNA level (23). RNA was isolated from parallel cultures to those grown for protein analyses using RNeasy Mini Kit (cat no 74104, Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). cDNA was synthesized using RT-PCR Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific / Finnzymes Vantaa, Finland). KAPA Probe fast qPCR Kit (KK4706, Kapa Biosystems, Boston, Massachusetts, USA) was used for qPCR. Four ng of template cDNA was used for analysing the expression levels of ATP2C1, desmoplakin, desmoglein 1 and 2, ZO-1, claudin 1 and betacatenin. Oligonucleotides were purchased from Oligomer, Helsinki, Finland. Primers used were Universal ProbeLibrary primers numbers 4, 56, 21, 66, 47, 77. The PCR analyses were carried out at the core facility of Turku Centre for Biotechnology, Turku, Finland.

Microarray analyses

Keratinocytes of third to fifth passages were used for microarray expression analyses. Cells grown to 40–60 % confluency were harvested for RNA isolation at time points of 0, 0.5, 4, 12, 24, and 48 hours after addition of high calcium medium. The sample preparation, hybridization and normalization protocols of these microarrays have been previously described (14). Agilent whole human genome microarray (G4112A; Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA) was used as the microarray platform. A total of 21 arrays were hybridized. The data were normalized using two methods: First, 2D loess, and second the quantile normalization (25,26). The expression levels of claudin 1, ZO-1, E-cadherin, betacatenin and desmoplakin were extracted from the log-transformed data. The Agilent platform used yielded two-channel data in which the expression in high calcium medium in each time point was compared to the mRNA levels in the low calcium medium at the same time point. In log2-transformed data value 1 thus corresponds to twofold change.

Western transfer analysis and antibodies

Western analysis was used to determine the effect of siRNA-mediated knock-down and to analyse the effect of SPCA1 silencing on junction proteins. Cells were harvested in RIPA buffer (2mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 50mM Tris pH 8, 150mM NaCl, 0,1% SDS, ddH2O, 1% NP40) containing phenylmethylsulphonylfluoride, dithiothreitol, sodiumorthovanadate and complete mini protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany). The proteins were separated on 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel and electroblotted onto Immobilon-P transfer membrane (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). The following primary antibodies were used: monoclonal antibodies against ATP2C1 (Clone 2G1, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), beta-actin (Clone AC-15, Sigma-Aldrich), betacatenin (clone 15B8, Sigma-Aldrich), ZO-1 (clone ZO1-1A12, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), claudin 4 (clone 3E2C1, Invitrogen), E-cadherin (13-1700, Invitrogen); and polyclonal antibodies for claudin 1 (37-4900, Invitrogen), desmoplakin (Ab71690, Abcam Cambridge, UK), occludin (71-1500, Invitrogen), desmoglein 2 (6D8) (26). Antibody for plakoglobin (11E4) has been described earlier (28). Horseradish peroxidase conjugated secondary antibodies for mouse IgG and rabbit IgG were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA, USA). The immunoreactions were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL; Amersham Biosciences, UK). Immunoreaction to beta-actin was used as a loading control. The radiographs were scanned and the results were analyzed using an open-source program, ImageJ (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/) (29). The densities of all junction protein bands were compared to the intensities of beta-actin bands of the same filter. Two-tailed unequal variance T-test was used to calculate p-values.

Immunofluorescence labeling

The cells were cultured on 8 Well Glass Slide, Lab-Tek Chamber Slide™ system 154534 (Nunc, NY, USA) and fixed in 100% methyl alcohol at −20°C. The samples were preincubated in 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS for 30 min. Primary antibodies (see above) were diluted in 1% BSA-PBS. Secondary antibodies were Alexa 568 conjugated goat anti rabbit and Alexa 488 conjugated goat anti mouse immunoglobulins (Invitrogen Carlsbad, CA, USA). The immunolabelled cultured cells were photographed with Zeiss AxioImager M1 microscope or Zeiss LSM 510 META confocal microscope equipped with AxioCam ICc3 camera and AxioVision Release 4.8 software or LSM 3.0 software, respectively. To visualize the immunoreactions in higher resolution, Leica TCS SP5 stimulated emission depletion (STED) microscope was used. For STED the secondary antibody was ATTO 647N (ATTO-TEC, Siegen, Germany), and the slides were mounted with Mowiol-DABCO (Sigma-Aldrich). Confocal imaging was performed at the Cell Imaging Core, Turku Centre for Biotechnology, and STED-imaging was performed at the Laboratory of Biophysics, Institute of Biomedicine and MediCity Research Laboratories, University of Turku.

Measurement of transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER)

TEER measurements of two different keratinocytes lines cultured in low and high calcium medium and transfected with siRNA46 or control siRNA were carried out. Six to nine replicates of each condition were measured in 24 hours after transfection and thereafter once a day up to three days. Measurements of transfected cultures maintained in low and high calcium medium were compared to siRNA transfected cells. Silencing of SPCA1 was controlled using western analysis of the cultures after TEER measurements. The transepithelial electrical resistance was measured using EVOM voltohmmeter (World Precision Instruments, Hertfordshire, UK). The TEER obtained from the monolayer and insert was subtracted with background TEER obtained from an empty insert to yield the monolayer resistance and multiplied with the area of the insert to obtain the result as ohm × cm2. Statistical significance was calculated with One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test. Statistical significance of p<0.05 was considered as significant. All statistical comparisons were done against the untreated control.

Results

SPCA1 inhibition by siRNA

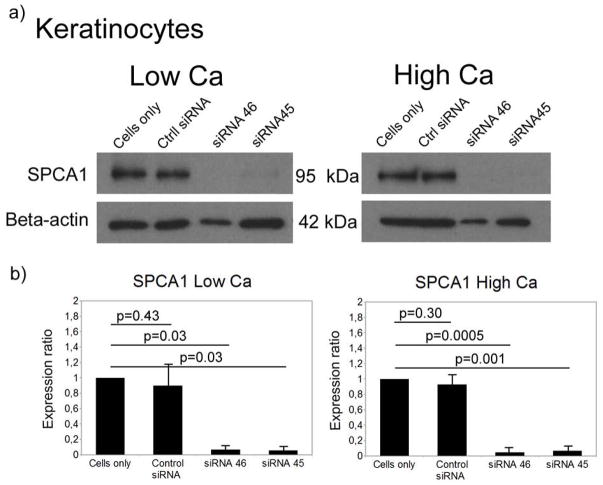

Transfection of normal human keratinocytes with two different siRNAs (siRNA 45 and siRNA 46) decreased SPCA1 protein to barely detectable level by western analysis (Fig. 1). This down-regulation persisted at least three days in cells cultured in low (0.06 mM) or high (1.2 mM) calcium concentration. The protein levels of SPCA1 in keratinocytes cultured in low or high calcium concentration were down-regulated by 93–95% using siRNA 45 and siRNA 46, when compared to control keratinocytes. As estimated by qPCR, the SPCA1 mRNA levels of keratinocytes cultured in low calcium concentration were down-regulated by 83% and 86% on treatment with siRNA 45 and siRNA 46, respectively, when compared to control. In high calcium concentration the reduction at the mRNA level was 44% (siRNA 45) and 72% (siRNA 46). The SPCA1 protein concentrations in siRNA inhibited cells were thus perhaps even lower than in HHD cells in which only one allele is mutated.

Figure 1.

Inhibition of ATP2C1 gene expression in keratinocytes cultured in low (0.06mM) or high calcium concentration (1.2mM). (a) Western analysis shows a clear decrease of the expression of SPCA1 protein in siRNA treated samples. (b) Quantification of Western analyses shows significant reduction of the SPCA1 protein by both siRNAs used.

The effect of elevated extracellular calcium on the expression of TJ components

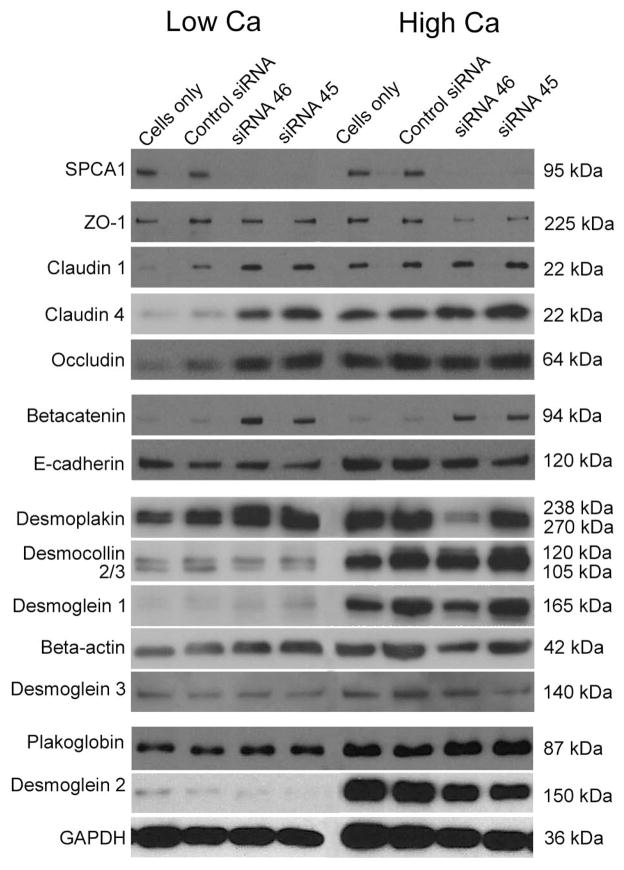

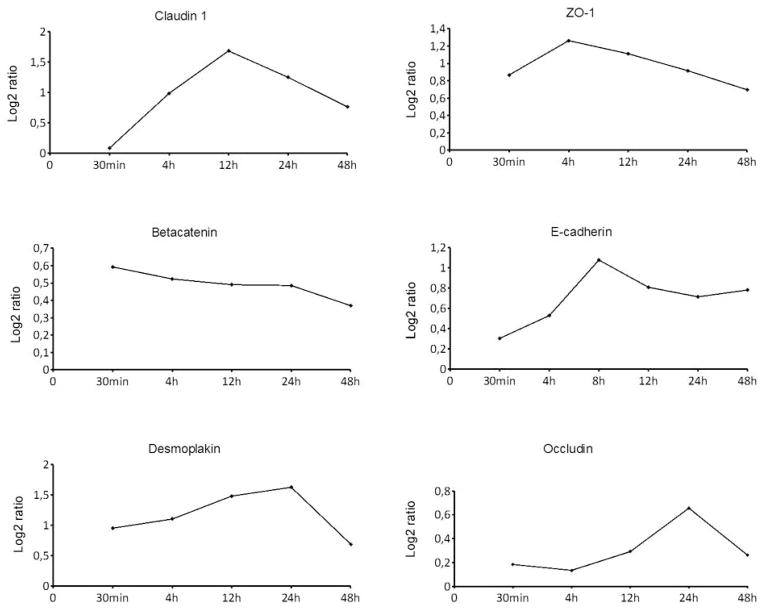

Western analysis (Figure 2) and cDNA microarrays (Fig 3) were used to evaluate the effect of calcium on selected TJ, desmosomal, and adherens junction proteins. The results of western analyses showed that control keratinocytes cultured in low calcium concentration synthesized all junction proteins at a relatively low level (Fig. 2 and supplement Fig. 1). In high calcium, the expression of tight junction proteins occludin, and claudins 1 and 4 increased and thus followed the same pattern as desmoplakin, plakoglobin, desmogleins 1, 2 and 3, desmocollins 2 and 3 and E-cadherin. The mRNA expression of claudin 1, E-cadherin, occludin, ZO-1, desmoplakin and beta catenin was elucidated using whole genome cDNA microarrays. The results showed that the mRNA levels of claudin 1, ZO-1, and occludin followed the same expression pattern as the expression of E -cadherin and desmoplakin, since the mRNA levels first increased after the switch to high calcium, after which the expression levels decreased (Fig. 3). The expression of betacatenin, however, followed a different pattern, steadily decreasing up to 48 hr. The increased claudin 1, E-cadherin and desmoplakin mRNA levels apparently translated to the accumulation of corresponding proteins since the protein levels were up-regulated in high calcium as shown by western analysis (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

The effect of SPCA1 inhibition on intercellular junction proteins. SiRNA inhibition (72 h) leads to significant changes in the protein expression of claudins 1 and 4. E-cadherin showed no changes after inhibition of SPCA1. Desmoplakin, desmogleins 1-3, desmocollins 2 and 3 and plakoglobin did not display marked changes.

Figure 3.

The influence of the calcium switch on mRNA expression of selected genes encoding intercellular junction components as studied using whole human genome DNA microarrays. The mRNA levels of claudin 1, E-cadherin, occludin, ZO-1 and desmoplakin increased during the first 4–24 hours after the switch to high calcium. Thereafter, the expression levels decreased. Betacatenin did not follow the same pattern.

The effect of SPCA1 inhibition on selected desmosomal, adherens and TJ proteins

The expression of intercellular junction proteins was studied in the SPCA1-deficient and control keratinocytes cultured in high or low calcium concentration using qPCR and western analysis. qPCR was used to study the mRNA levels of desmoplakin, desmogleins 1 and 2, betacatenin, claudin 1 and ZO-1 three days after transfection. The mRNA level of claudin 1 increased 145 % and 247 % in low calcium cultures and 229% and 244% in high calcium cultures using siRNAs 45 and 46, respectively, while the levels of betacatenin, desmogleins 1 and 2 and desmoplakin were comparable to those of controls. The mRNA level of ZO-1 however decreased 73 % and 46 % in low calcium cultures and 51% and 23% in high calcium cultures using siRNAs 45 and 46.

In western analyses, SPCA1-deficient keratinocytes displayed higher levels of claudins 1 and 4 already when maintained in low calcium concentration which is in contrast to control keratinocytes. Specifically, claudin 1 was elevated by 73%/69% and claudin 4 by 464%/270%, when treated with siRNAs 45 and 46, respectively. Occludin did not however show significant changes. ZO-1 did not follow the same pattern as claudins since the levels of ZO-1 were reduced by 58%/52%. For betacatenin the results using the different siRNAs yielded contradicting results, one siRNA increasing the expression and the other siRNA decreasing it (Supplement Fig. 1). siRNA inhibition did not markedly alter the protein levels of E-cadherin, desmoplakin, desmogleins (1, 2, and 3), or plakoglobin (Fig. 2 and supplement Fig. 1).

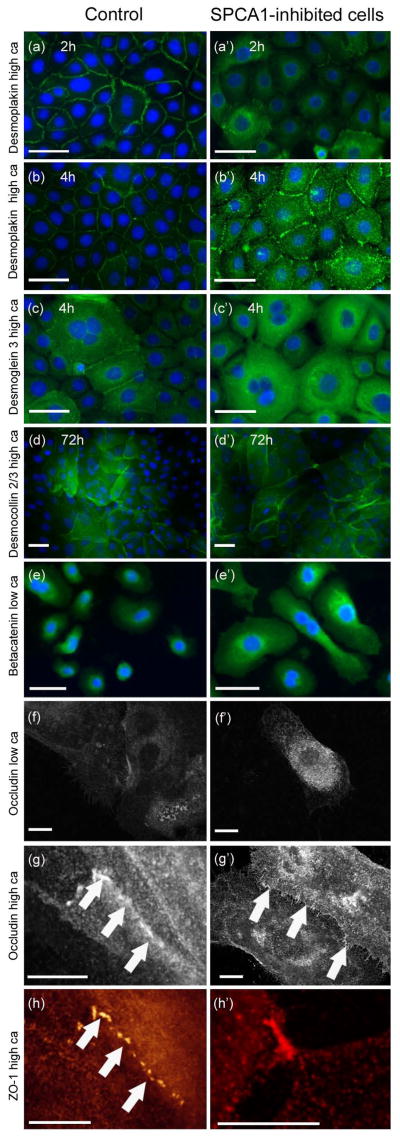

Morphological changes in SPCA1-inhibited keratinocytes

Indirect immunofluorescence labeling for junction proteins was carried out to study the effect of the SPCA1 inhibition at the morphological level. After transfection the keratinocytes were maintained in low calcium for 3 days to deplete the cells of SPCA1 protein. Then the cells were allowed to differentiate in high calcium for 1, 2, 4, 8 and 24 hours. Fluorescence microscope, confocal laser scanning microscope, and STED (stimulated emission depletion microscopy) were used to visualize the immunoreactions in more detail. This experiment revealed that translocation of desmoplakin and desmoglein 3 to desmosomes was delayed in SPCA1-inhibited cells compared to controls during the first 2–4 hours (Fig. 4a–c′), but by 24h the desmosomes in SPCA1 inhibited and control cells did not differ from each other. Thus, the formation of desmosomes was delayed in SPCA1-deficient keratinocytes but in longer incubations in high calcium medium the desmosomes were apparently similar to those in control cells (Fig. 4a′–b′). The intracellular fluorescence intensity for desmoplakin and desmoglein 3 as well as betacatenin was higher in SPCA1 inhibited cells (Fig. 4a′–e′). Confocal microscopy (Fig. 4g–g′) and STED microscopy (Fig. 4h–h′) revealed accumulation of ZO-1 and occludin in a zipper-like manner at the cell-cell contact sites. In low calcium medium, SPCA1 deficient cells showed increased intracellular accumulation of occludin, claudin 4 (Fig. 4f′, supplement Fig. 2 f′) and betacatenin (Fig. 4e′). However, in high calcium the SPCA1 inhibition did not seemingly alter the formation of adherens junctions or TJs (Fig. 4e–h′, supplement Fig. 2 c–g′).

Figure 4.

Indirect immunofluorescence labeling of control (a)–(h) and SPCA1 inhibited keratinocytes (a′)–(h′) for intercellular junction proteins. Panels (a)–(e′) were visualized using fluorescence microscope, panels (h)–(h′) using STED microscope and panels (f)–(g′) were photographed with confocal laser scanning microscope. Localization of desmoplakin (a)–(b′) and desmoglein 3 (c)–(c′) to intercellular junctions was delayed in SPCA1 inhibited cells after switch to high calcium medium. Instead, the cytoplasmic labeling of desmoplakin and desmoglein 3 was increased in SPCA deficient cells compared to controls. (d)–(d′) Desmomocollin 2/3 localizes to desmosomes in 72h incubation in high calcium medium. (e)–(e′) SPCA1 inhibition increased intracellular betacatenin in keratinocytes cultured in low or high calcium. Labeling for occludin (f)–(g′) in SPCA1 inhibited keratinocytes cultured in low calcium show a more intense immunosignal for intracellular occludin than control cells. (g)–(g′) Occludin localizes to the intercellular junctions in cells cultured in high calcium (arrows). (g) and (h) show colocalization of ZO-1 and occludin in zipper-like TJs as demonstrated by confocal and STED microscopy. (g′) and (h′) reveal the finger-like TJ sites (arrows). Scale bars 50 μm in (a)–(e′). Scale bars 10 μm in (f)–(h′).

Measurement of transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER)

TEER measurements of two different keratinocyte lines were carried out. Six to nine replicates of each condition were measured in 24 hours after transfection and thereafter once a day up to three days. The results showed 152% increase in the electric resistance in SPCA1 inhibited cells cultured in low calcium medium for 24 hours while no significant change could be demonstrated in cells cultured in high calcium medium.

Discussion

The expression of SPCA1 mRNA and protein levels were successfully down-regulated using siRNA transfection and the effects on the mRNA and protein expression of selected desmosomal, adherens and TJ proteins was subsequently monitored.

Acantholysis, the main pathological feature seen in HHD epidermis, has been considered to be the final result of a desmosomal defect, but it is not known how the deficiency affects the dynamics of desmosome and adherens junction assembly or disassembly. When designing this study we hypothesized that the lack of SPCA1 might affect the synthesis or processing of desmosomal components. It was thus unexpected that SPCA1 inhibition did not have any effects on the protein levels of desmoplakin, desmogleins 1-3, desmocollin 2/3 or plakoglobin. However, translocation of desmoplakin and desmoglein 3 to desmosomes was delayed in differentiating SPCA1 inhibited keratinocytes, which may compromise the assembly of desmosomes and the epidermal integrity in vivo.

In parallel with the desmosomal components we studied the effects of SPCA1 inhibition on selected TJ and adherens junction components. SPCA1 inhibition significantly increased claudin 1 and 4 protein levels when the cells were cultured in low calcium concentration. ZO-1 did not follow the same pattern and changes in occludin expression were not significant suggesting that TJ proteins are differentially regulated as the result of SPCA1 inhibition. SPCA1-deficiency did not affect the levels or translocation of adherens junction proteins E-cadherin or betacatenin in low or high calcium. The changes of mRNA levels corresponded to the changes seen at the protein level in both low and high calcium concentration. The increased transepithelial electric resistance in SPCA1 inhibited cells in low calcium suggested that the increased claudin levels may lead to altered cellular function. In normal human epidermis, TJs are localized to the stratum granulosum (19, 20) where the extracellular calcium concentration is high (6,13). Our previous study on TJs in HHD epidermis showed that TJs and desmosomes display different dynamics in acantholytic cells (22). Specifically, desmosomal components are seen intracellularly while TJ proteins remain at the junctional areas. We have previously shown that the formation of TJs in cultured keratinocytes takes place in the presence of high calcium (19). The intracellular resting calcium concentration of HHD keratinocytes is reported to be either normal (7) or higher than normal (6). Since the intracellular calcium levels were not measured in the present study we can only speculate that the lack of the SPCA1 protein leads to altered intracellular Ca2+ metabolism which contributes to increased claudin 1 and 4 synthesis.

To conclude, the current results show that the desmosomal and TJ proteins are differently regulated on SPCA1 knockdown. These studies also link intracellular calcium regulation and TJs for the first time showing that interfering with SPCA1 leads to aberrant expression of claudins 1 and 4.

Supplementary Material

Quantification of selected western analyses. Mean values of four to six independent western analyses were included in the diagram. In the SPCA1 inhibited keratinocytes, the levels of claudins 1 and 4 showed an increase already in low calcium concentration. In contrast, the elevation of calcium concentration was needed to increase the protein expression in control cells.

Keratinocytes cultured in high calcium for 72 hours and immunolabeled for intercellular junction proteins (a–b′, d–e′, g–g′). Desmoplakin, desmoglein 3, E-cadherin, betacatenin and claudin 4 localized to the intercellular junctions in control and SPCA1 deficient keratinocytes. (f)– (f′) Cells with intracellular accumulation of claudin 4 were more numerous in SPCA1 inhibited keratinocytes in low calcium compared to control cultures where only few claudin 4 positive cells could be found. (c)–(d′) SPCA1 inhibition did not change the expression of E-cadherin. Scale bars 50 μm.

Acknowledgments

We thank Miso Immonen for his help in cell culturing and Kirsti Tiihonen from DuPont Nutrition and Health for collaboration in TEER analyses. This work was supported by grants from The Finnish Dermatological Society, Turku University Foundation, The Research Foundation for Laboratory Medicine, Turku Duodecim Society, the Finnish Academy and Turku University Hospital EVO funding.

Footnotes

Author’s contributions

Laura Raiko (A, B, C, D, E, G, H), Elina Siljamäki (A, B, C, E), M3 G. Mahoney (B, C, D, F), Heli Putaala (A, F, G), Erkki Suominen (C, F), Juha Peltonen (A, B, C, F), Sirkku Peltonen (A, B, C, E, F, G, H)

(A) contribution to research design or acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data, (B) drafting the paper or revising it critically, (C) approval of the submitted and final version, (D) performed the research, (E) designed the research study, (F) contributed to the essential reagents or tools, (G) analysed the data, and (H) wrote the paper

Conflict of interest

The authors report no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Burge SM. Br J Dermatol. 1992;126:275–282. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1992.tb00658.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Palmer D, Perry H. Arch Dermatol. 1962;86:493–502. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1962.01590060050010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sudbrak R, Brown J, Dobson-Stone C, et al. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9:1131–1140. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.7.1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hu Z, Bonifas JM, Beech J, et al. Nat Genet. 2000;24:61–65. doi: 10.1038/71701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Foggia L, Hovnanian A. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2004;131(C):20–31. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Behne MJ, Tu C-L, Aronchik I, et al. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;4:688–694. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12528.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leinonen PT, Myllylä RM, Hägg PM, et al. Brit J Dermatol. 2005;153:113–117. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06623.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ramos-Castañeda J, Park Y, Liu M, et al. J Biol Chem. 2005;10:9467–739. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413243200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Missiaen L, Raeymaekers L, Dode L, et al. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;4:1204–1213. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.07.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carnell L, Moore H-PH. J Cell Biol. 1994;3:693–705. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.3.693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burge SM, Garrod DR. Br J Dermatol. 1991;124:242–251. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1991.tb00568.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hakuno M, Shimizu H, Akiyama M, et al. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:702–711. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leinonen PT, Hägg PM, Peltonen S, et al. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;6:1379–1387. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Manca S, Magrelli A, Cialfi S, et al. Exp Dermatol. 2011;20:932–937. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2011.01359.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Desai BV, Harmon RM, Green KJ. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:4401–4407. doi: 10.1242/jcs.037457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Furuse M, Hata M, Furuse K, et al. J Cell Biol. 2002;156:1099–1111. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200110122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Turksen K, Troy TC. Development. 2002;129:1775–1784. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.7.1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Troy TC, Rahbar R, Arabzadeh A, et al. Mech Dev. 2005;122:805–819. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2005.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pummi K, Malminen M, Aho H, et al. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;117:1050–1058. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-202x.2001.01493.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brandner JM, Kief S, Grund C, et al. Eur J Cell Biol. 2002;81:253–263. doi: 10.1078/0171-9335-00244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peltonen S, Riehokainen J, Pummi K, Peltonen J. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:466–472. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07642.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Raiko L, Leinonen P, Hägg PM, Peltonen J, Oikarinen A, Peltonen S. Dermatology Reports. 2009;1:1–5. doi: 10.4081/dr.2009.e1. http://www.pagepress.org/journals/index.php/dr/article/viewArticle/dr.2009.e1/1609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boyce ST, Ham RG. J Invest Dermatol. 1983;81(1 Suppl):33s–40s. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12540422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ. Nature Protocols. 2008;6:1101–1108. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smyth GK, Speed T. Methods. 2003;31:265–273. doi: 10.1016/s1046-2023(03)00155-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tuimala J, Saarikko I, Laine MM. DNA Microarray Data Analysis. 2. Helsinki: CSC Scientific Computing; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brennan D, Mahoney MG. Cell Adh Migr. 2009;2:148–154. doi: 10.4161/cam.3.2.7539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wahl JKR. Hybrid Hybridomics. 2002;21:37–44. doi: 10.1089/15368590252917629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gassmann M, Grenacher B, Rohde B, Vogel J. Electrophoresis. 2009;30:1845–1855. doi: 10.1002/elps.200800720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Quantification of selected western analyses. Mean values of four to six independent western analyses were included in the diagram. In the SPCA1 inhibited keratinocytes, the levels of claudins 1 and 4 showed an increase already in low calcium concentration. In contrast, the elevation of calcium concentration was needed to increase the protein expression in control cells.

Keratinocytes cultured in high calcium for 72 hours and immunolabeled for intercellular junction proteins (a–b′, d–e′, g–g′). Desmoplakin, desmoglein 3, E-cadherin, betacatenin and claudin 4 localized to the intercellular junctions in control and SPCA1 deficient keratinocytes. (f)– (f′) Cells with intracellular accumulation of claudin 4 were more numerous in SPCA1 inhibited keratinocytes in low calcium compared to control cultures where only few claudin 4 positive cells could be found. (c)–(d′) SPCA1 inhibition did not change the expression of E-cadherin. Scale bars 50 μm.