Abstract

The collecting duct cell types giving rise to cysts in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease are unknown. To study this, transgenic mice expressing Cre recombinase under control of the aquaporin-2 promoter were bred with mice containing loxP sites within introns 1 and 4 of the Pkd1 gene, thereby generating principal cell-specific knockout of Pkd1. Similarly, transgenic mice expressing Cre recombinase under the control of the B1 subunit of the proton ATPase promoter were bred with loxP-flanked Pkd1 animals to generate intercalated cell specific knockout of Pkd1. Principal cell knockout mice developed progressive cystic kidney disease evident at one week postnatal and had an average lifespan of 8.2 weeks. There was no change in cellular cAMP content or membrane aquaporin-2 expression in the cystic kidney. Cysts were present in the cortex and outer medulla, but were absent in the papilla. Intercalated cell knockout mice had a very mild cystic phenotype limited to 1–2 cysts/kidney as late as 13 weeks of age that were confined to the outer rim of the cortex. These mice lived to at least 1.5 years of age without evidence of early mortality. These findings suggest that principal cells are more important than intercalated cells in cyst formation in polycystic kidney disease.

INTRODUCTION

Renal cysts in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) arise from cells throughout the nephron. Analysis of human ADPKD cyst fluid reveals two major cyst types; one with sodium and chloride hypotonic to plasma (presumably derived from distal nephron) and the other with sodium and chloride isotonic to plasma (thought to derive from proximal nephron).1 Immunohistochemical studies, using stains for aquaporins, lectins and other markers have yielded variable results, but suggest that a substantial percentage of cysts in ADPKD arise from distal nephron, including collecting duct.2–5 Within the collecting duct, there is uncertainty as to whether both cell types, namely intercalated (IC) and principal (PC) cells, give rise to cysts. No studies have determined the collecting duct cellular pattern of expression of the proteins responsible for ADPKD, polycystin-1 and -2 6, 7; this relates to the lack of antibodies with adequate sensitivity and specificity. A second key point relates to primary cilia expression by these cell types. Numerous studies have implicated the primary cilium as a key factor in cystogenesis since mutations of multiple different ciliary proteins lead to renal cyst formation 5; both polycystin-1 and -2 are spatially associated with the primary cilium 8. Ultrastructural studies done over 45 years ago detected primary cilia on rat principal, but not intercalated cells.9 This conclusion was supported by one subsequent study (in 1989) focused on rat inner medullary collecting duct (which has very few intercalated cells).10 In contrast, modern technology has clearly shown that, in the mouse, both principal and intercalated cells contain primary cilia. A recent report found that mouse intercalated cells have a primary cilium by staining for acetylated alpha-tubulin (a marker of the ciliary axoneme) as well as by scanning electron microscopy.11 Thus, based on the above considerations, there is no compelling reason a priori to suspect that intercalated cells are unable to give rise to cysts in ADPKD.

An animal model of ADPKD would be ideal to evaluate the role of IC and PC in cyst formation. Several models of autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease exist, including congenital polycystic kidney (cpk) mice, oak ridge polycystic kidney (Tg737) mice, and polycystic kidney (pck) rats12 However, these involve mutations in proteins other than polycystin-1 and -2. A number of animal models of ADPKD exist, however most of these have proven to be problematic. Mice with homozygous mutations of the mouse orthologues of the human genes encoding polycystin-1 and -2 (Pkd1 and Pkd2) die in utero due to multiple organ involvement, some of which is not typical for ADPKD.13–17 Heterozygous Pkd1 and Pkd2 knockout mice develop limited renal cysts late in life and have not, therefore, been highly useful for analysis.13, 16 The Pkd2WS25 model is perhaps most similar to human ADPKD18 In this spontaneous loss of heterozygosity model, recombination of the Pkd2WS25 allele leads to renal cysts if the animal contains a Pkd2 null allele. However, since PKD1 mutations account for the large majority of cases of ADPKD, continued efforts have focused on targeting this allele. These approaches have largely utilized renal-specific knockout of Pkd1 in mice. One model used mice expressing the gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase promoter coupled to Cre recombinase and loxP-flanked (floxed) Pkd1 exons 2–6.19 These animals developed proximal and distal nephron cysts and survived about 4 weeks - long enough to examine potential signaling pathways, but limiting more long-term analysis. A similar strategy was employed wherein Ksp-Cre transgenic mice were bred with mice containing floxed exons 2–4 in Pkd1.11 This resulted in Cre expression selectively in thick ascending limb through collecting duct, however the animals survived only three weeks, perhaps because of early (E11.5) Cre expression. To overcome early lethality, mice were generated with tamoxifen-inducible Pkd1 deletion using a Ksp-CreERT2 transgene and floxed Pkd1 exons 2–11.20 When Pkd1 is disrupted at 3–6 months, a mild cystic phenotype is obtained, but when Pkd1 is disrupted at 4 days of age, severe cyst formation occurs. This latter model may hold the greatest promise for studying cystogenesis in ADPKD, however it is still not possible, due to the issues described above, to determine the collecting duct cell type of origin of the cysts. To address this, the current study employed a Cre/loxP strategy to selectively mutate Pkd1 in PC and IC. We report a marked difference in the severity of cystic kidney disease in these two new mouse models of ADPKD.

RESULTS

Characterization of principal cell polycystin-1 knockout (PC-Pkd1 KO) mice

Eighty-one of 389 pups (20.8%) were PC-Pkd1 KO (homozygous for the Pkd1cond allele and heterozygous for the AQP2-Cre transgene). One hundred-five animals (27.0%) were homozygous for the Pkd1cond allele, but did not have the AQP2-Cre transgene. Ninety-four animals (24.2%) were heterozygous for the Pkd1cond allele and contained the AQP2-Cre transgene. One hundred-nine animals (28.0%) were heterozygous for the Pkd1cond allele, but did not have the AQP2-Cre transgene. These genotype frequencies were not significantly different (p = 0.18).

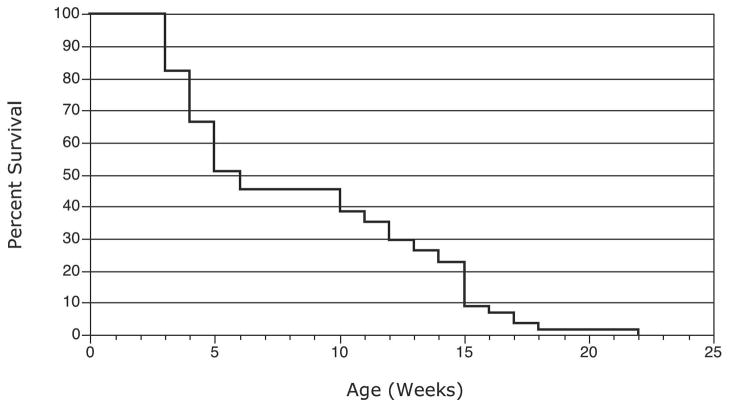

Fifty-seven PC-Pkd1 KO animals were kept with littermates until natural death. The mean survival of PC-Pkd1 KO animals was 8.2 weeks (range 2.1–21.6 weeks, SE +/−0.7) (Figure 1). Five animals each of the three other genotypes were kept alive for comparison and all remained alive at 78 weeks (1.5 years). Thus, heterozygous PC-Pkd1 KO mice had a normal life span.

Figure 1.

The mean survival of 57 PC-Pkd1 KO mice was 8.2 weeks (range 2.1–21.6, SE +/− 0.7).

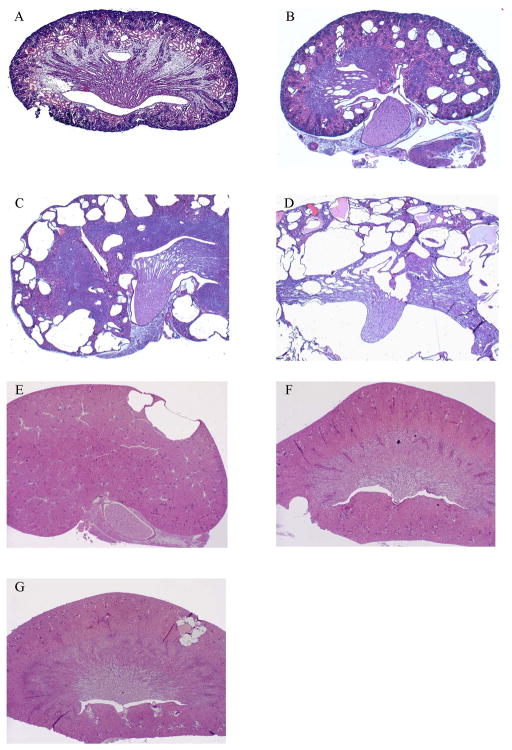

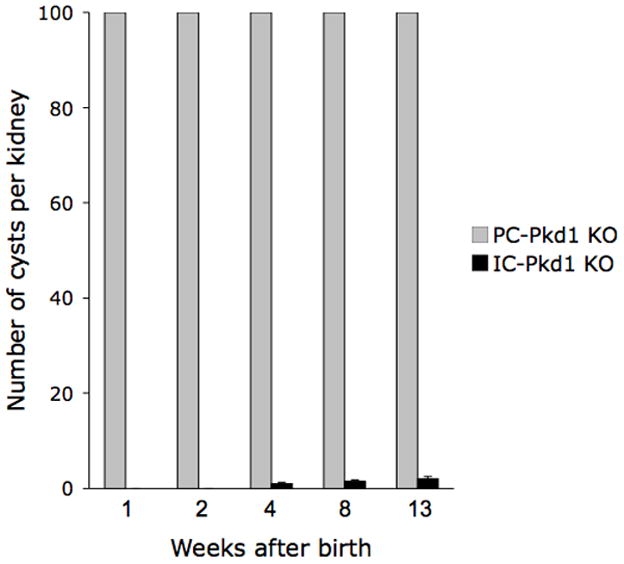

At birth, there were no macroscopic or microscopic renal cysts. Bilateral renal cysts were grossly apparent in all PC-Pkd1 KO mice at week 1, with progressive cyst formation and enlargement through week 4 (Figure 2A – 2D) and Figure 3A. Total cysts per kidney exceeded 100 starting on week 1 (Figure 4). Cysts were most apparent in the cortex and outer medulla, whereas cysts were not observed in the papilla. Real-time PCR for polycystin-1 mRNA in papillary collecting duct from wild-type mice showed this region contains 1.46 times the amount of polycystin-1 mRNA (normalized to GAPDH) as compared to outer medulla. Hence, the absence of papillary cysts is not due to failure of papillary CD to express polycystin-1 mRNA. No cysts were apparent macroscopically or microscopically in any control animals sacrificed at any time point from week 1 through 39 weeks of age. No gross abnormalities were present in non-renal organs in PC-Pkd1 KO mice.

Figure 2.

Representative sections of PC-Pkd1 KO mice (A–D) and IC-Pkd1 KO mice (E–G) stained with hematoxylin and eosin. A) PC-Pkd1 KO at birth, 4x. B) PC-Pkd1 KO at 1 week, 2x. C) PC-Pkd1 KO at 2 weeks, 2x. D) PC-Pkd1 KO at 4 weeks, 2x. E) IC-Pkd1 KO at 4 weeks. F) IC-Pkd1 KO at 8 weeks. G) IC-Pkd1 KO at 13 weeks.

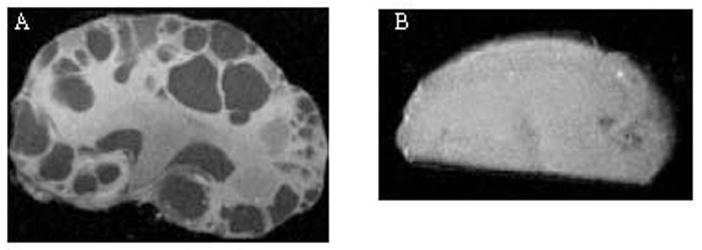

Figure 3.

Representative MRIs of kidneys obtained from (A) PC-Pkd1 KO and (B) IC-Pkd1 KO. The MRIs are from PC-Pkd1 KO mice at 2 weeks of age and IC-Pkd1 KO mice at 13 weeks of age.

Figure 4.

Number of cysts at varying ages in PC-Pkd1 KO and IC-Pkd1 KO mice. PC-Pkd1 KO bars are at maximal height - these kidneys had greater than 100 cysts. N=10 kidneys each data point.

Staining for DBA confirmed that cysts are of collecting duct origin (Figures 5A and 5B). AQP2 expression of cystic epithelium was variable – some cysts displayed circumferential staining, some with no staining, and others with partial staining (images not shown). The presence of renal cysts at week 1 and thereafter was associated with a higher kidney weight (Figure 6A). Body weight was less than control animals at 4 weeks and thereafter (Figure 6B). Renal insufficiency was evident as early as week 2: BUN in PC-Pkd1 KO was 41.2 mg/dL (n=4, SE +/− 8.4) versus 19.2 mg/dL (n=5, SE +/− 1.2) in control animals (p=0.0224). Severe renal insufficiency was evident at 4 and 8 weeks of age (Figure 6C).

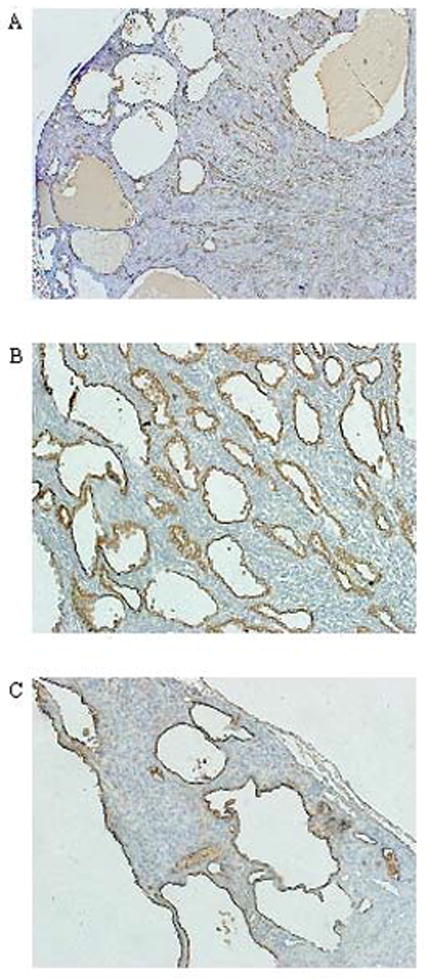

Figure 5.

Representative sections of PC-Pkd1 KO (A–B) and IC-Pkd1 KO mice (C) stained with DBA (brown) showing collecting duct origin of cysts. A) PC-Pkd1 KO at week 4, 2x. B) PC-Pkd1 KO at week 4, 20x. C) IC-Pkd1 KO at week 13, 20x.

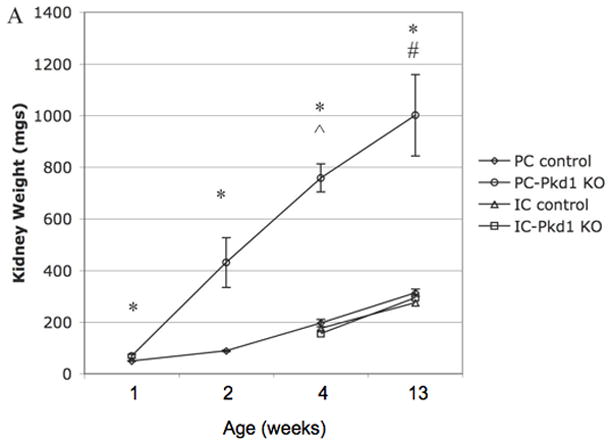

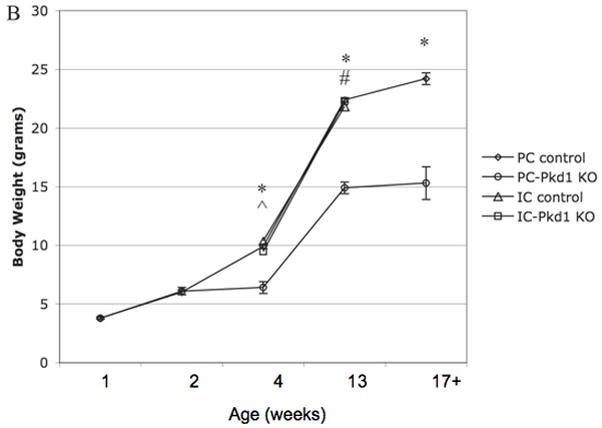

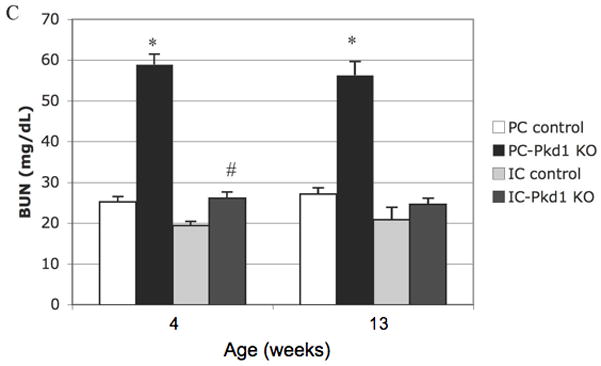

Figure 6.

(A) Kidney weight of PC-Pkd1 KO and IC-Pkd1 KO expressed as mean and standard error. * p < 0.0001 for the comparison of PC-Pkd1 KO and PC controls at weeks 1, 2, 4 and 8. ^ p = 0.0001 at 4 weeks and # p = 0.0026 at 8 weeks for the comparison of PC-Pkd1 KO and IC-Pkd1 KO. Kidney weight between IC-Pkd1 KO and IC controls was NS different. (B) Body weight of PC-Pkd1 KO and IC-Pkd1 KO expressed as mean and standard error. * p < 0.0001 for the comparison of PC-Pkd1 KO and PC controls at 4, 8 and 13 weeks. Body weight was NS different at D7 and D14. ^ p = 0.024 at 4 weeks and # p = 0.0026 at 8 weeks for the comparison of PC-Pkd1 KO and IC-Pkd1 KO. Body weight between IC-Pkd1 KO and IC controls was NS different. (C) BUN of PC-Pkd1 KO and IC-Pkd1 KO expressed as mean and standard error. * p < 0.0001 for the comparisons of PC-Pkd1 KO versus PC controls and PC-Pkd1 KO versus IC-Pkd1 KO at 4 and 13 weeks. # p = 0.0054 for the comparison of IC-Pkd1 KO and IC controls at 4 weeks. The difference between IC-Pkd1 KO and IC controls at 13 weeks was NS.

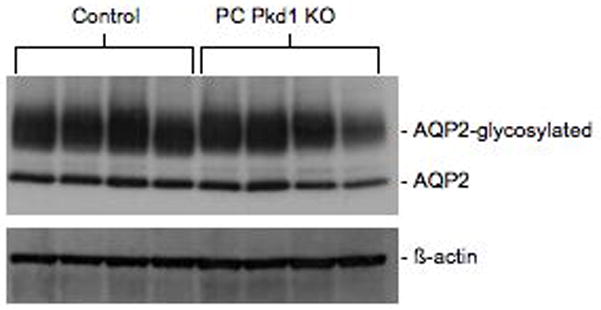

In order to determine if there were alterations in cAMP levels or expression of the target protein, AQP2, total kidney cAMP content and membrane-associated AQP2 protein levels were ascertained. There was no difference in cAMP content between 4-week old PC-Pkd1 KO mice (105.1 ± 14.9 pmol cAMP/mg total cell protein, n=5) and controls (125.0 ± 17.1 pmol cAMP/mg total cell protein, n=5). Similarly, there were no differences in glycosylated or unglycosylated AQP2 levels between PC-Pkd1 KO and control mice (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Western blot of glycosylated and unglycosylated AQP2 levels in 4-week old PC-Pkd1 KO and control mice. Data are shown from 4 separate mice in each group.

Characterization of intercalated cell polycystin-1 knockout (IC-Pkd1 KO) mice

Twenty-six of 86 mice (30.2%) were IC-Pkd1 KO: homozygous for the Pkd1cond allele and contained the B1-Cre transgene. Seventeen animals (19.8%) were homozygous for the Pkd1cond allele, but did not have the B1-Cre transgene. Twenty animals (23.3%) were heterozygous for the Pkd1cond allele and contained the B1-Cre transgene. Twenty-three animals (26.7%) were heterozygous for the Pkd1cond allele, but did not have the B1-Cre transgene. These genotype frequencies were not significantly different (p = 0.55).

In comparison to PC-Pkd1 KO, IC-Pkd1 KO animals had a very mild cystic phenotype (Figures 2E – 2G, 3 and 4). Two of the five IC-Pkd1 KO animals sacrificed after 4 weeks had no cysts macroscopically or microscopically. One animal had one macroscopic cyst in one kidney. Another animal had two macroscopic cysts in one kidney and three in the other. The fifth had one macroscopic cyst in one kidney and an additional microscopic cyst in the contralateral kidney. All cysts at 4 weeks of age were limited to the cortex.

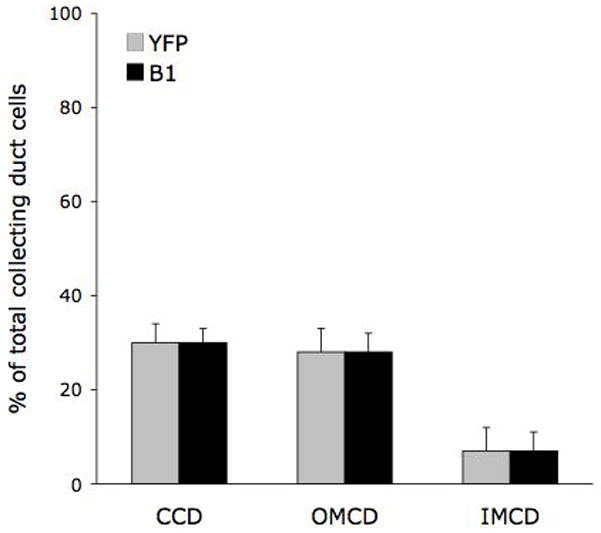

At 8–9 weeks of age, one of five IC-Pkd1 KO mice had no renal cysts. The remaining four had 1–2 macroscopically apparent cysts in each kidney. As in the 4-week old animals, cysts were limited to the cortex. At 17 weeks, all five animals had cysts in both kidneys (Figures 3 and 4). These averaged 2 cysts per kidney. Most cysts in animals at this age were relatively small (as compared to cysts in PC-Pkd1 KO mice). Intercalated cells represent about 30% of cortical and outer medullary collecting duct cells (Figure 8), hence the extremely low number of cysts in IC-Pkd1 KO mice, as compared to PC-Pkd1 KO mice, is not due to the number of intercalated cells.

Figure 8.

Number of intercalated cells in mouse collecting duct. Sections of control mouse kidneys were immunostained for the V-ATPase B1subunit (B1), and the percent of B1 positive cells (compared to total collecting duct cells) in a given region of kidney determined. The percent of intercalated cells within the collecting duct was also assessed by breeding B1-Cre mice with reporter mice transgenic for ROSA26 -YFP; YFP-positive intercalated cells were yellow. Each data point represents counting of 10 sections per kidney in 5 kidneys. CCD - cortical collecting duct; OMCD - outer medullary collecting duct; IMCD - inner medullary collecting duct.

Body weight and kidney weight were not different between IC-Pkd1 KO and littermate controls, and were not different than PC-Pkd1 controls (Figures 6A and 6B). The BUN at 4 weeks was higher in IC-Pkd1 KO than in littermate controls, but not likely meaningful since the BUN at 17 weeks was similar. (Figure 6C). BUN in IC-Pkd1 KO was not different than BUN in PC-Pkd1 controls (Figure 6C). No abnormalities were grossly apparent in any non-renal organs in IC-Pkd1 KO animals and no cysts were observed in any control animal through 39 weeks of age. No IC-Pkd1 KO animals died during 78 weeks (1.5 years) of follow-up (N=10).

DISCUSSION

In this study, two new mouse models of ADPKD were created. The PC-Pkd1 KO mice were generated using the AQP2-Cre mice which express Cre selectively in renal principal cells and in male reproductive tract.21–24 The PC-Pkd1 KO mice have a severe, yet viable, kidney-limited cystic phenotype. Animals develop cysts at one week of age, renal insufficiency at two weeks, and progressive kidney enlargement and cyst growth. These mice have an average life span of 8.2 weeks with a wide range in survival. Thus, principal cell polycystin-1 dysfunction can, in of itself, cause profound renal cystic disease.

The IC-Pkd1 KO model was generated using the B1-Cre mice which express Cre selectively in intercalated cells within the kidney; these mice have low level Cre expression in brain, intestine and uterus.25 The IC-Pkd1 KO mice had very few cysts with minimal to no impairment in renal function. Cysts in IC-Pkd1 KO mice were largely confined to the cortex, and particularly near the capsule. This very mild phenotype and renal cyst localization is not due to incomplete IC Cre expression; B1-Cre mice confer virtually 100% IC-specific target gene recombination throughout the cortex and outer medulla as evidenced by crossing B1-Cre mice with ROSA26-YFP reporter animals.25 Furthermore, we found that IC constitute 30% of the collecting duct cell types in the cortex and 28% in the outer medulla (another study found that IC make up 40% of the cortical and outer medullary collecting duct cells26), hence the low number of cysts and their absence in outer medulla is not due to limited numbers of IC. Since it is currently not possible to localize polycystin-1 protein or mRNA to specific collecting duct cell types, the reasons for the limited number of cysts and the failure to form outer medullary cysts are speculative. Mouse IC contain a primary cilium11, hence failure to form cysts is not due to lack of this structure. It may be that IC lack expression of, and/or functionally important, polycystin-1. In this regard, it is possible that cysts in IC-Pkd1 KO mice arise solely from the connecting segment. B1-Cre-mediated recombination (using the ROSA26-YFP reporter mice) occurs in connecting segment cells that co-express AQP225, hence it is conceivable that these “hybrid” cells, which have features of both IC and PC, express the V-ATPase characteristic of ICs as well as functionally important polycystin-1. Confirmation of this is problematic since there is no way to specifically target connecting segment. Furthermore, segmental nephron markers are largely lost in cystic epithelium and do not accurately identify the cell type of origin.27 Thus, while the current data suggest that collecting duct and connecting segment cysts in ADPKD arise only from cells with principal cell characteristics, confirmation is required.

PC-Pkd1 KO mice do not express cysts in the renal papilla, yet mouse papillary collecting ducts possess a primary cilia11 and polycystin-1 mRNA levels that exceed those in the outer medulla. Failure to express Cre recombinase in the papillary collecting duct is not the reason for cyst absence since AQP2-Cre mice express active Cre in virtually every principal cell in this nephron segment.21–24, 28 In contrast, in the Ksp-Cre Pkd1 model, tubule ectasia is apparent in the renal papilla.11 The reason for the different papillary phenotypes is uncertain, but may relate to differences in the timing of Cre expression: Cre is active much earlier in renal development in Ksp-Cre Pkd1 mice (E11.5) as compared to PC-Pkd1 KO mice (E18.5).

The mechanisms responsible for massive cyst formation in PC-Pkd1 KO mice remain conjectural. While cystogenesis is strongly associated with defective cilia, there is no evidence to suggest that deficiency of polycystin-1 in principal cells leads to structural abnormalities in cilia. Studies in Pkd1 KO endothelial cells 29, epithelial cells lining kidney cysts from patients with ADPKD 30–32, and in C. elegans with disruption of a Pkd1 homologue 33 all indicate that primary cilia are present and are grossly intact. More specifically, collecting duct cells from mice with Pkd1 disruption have grossly intact primary cilia. 11, 34 In addition, the current studies found no evidence that AQP2 levels or cellular cAMP content were altered in PC Pkd1 KO mice. These observations are of interest in that vasopressin can directly regulate cyst growth in a model of ADPKD 35, cAMP stimulates human PKD epithelial cell growth and fluid secretion 36, and V2 receptor antagonism reduces cystic disease in animal models. 37 Further, renal cAMP levels have been reported to be elevated in PKD. 38 In contrast, our findings suggest that an overall increase in renal cAMP content or downstream vasopressin and cAMP targets (AQP2) do not invariably occur, at least insofar as principal cell-derived cysts are concerned. A wide variety of other signaling pathways have been invoked in cystogenesis 39 - exploration of these possibilities, some of which may be of greater importance in principal cells, would be of substantial interest. Finally, our studies do not preclude the possibility that V2 receptor activation and cAMP are important - such conclusions could only be assessed by examining the effect of V2 antagonism in this model.

There are both limitations and advantages of the PC-Pkd1 KO mouse model. The “two-hit” hypothesis proposes that a mutation of the normal PKD1 allele, or a somatic modifier gene, occurs before the development of renal cysts. In the PC-Pkd1 KO model, animals are born with two mutant Pkd1 alleles. Another potential limitation is that in human ADPKD, cysts develop from all nephron segments, whereas cysts arise only from the collecting duct in the PC-Pkd1 KO model. Third, in the PC-Pkd1 KO mouse, cysts develop shortly after birth; this necessitates administration of agents to the mother, and adequate secretion into breast milk, in order to examine the effect of early drug intervention in disease progression. Despite these limitations, the PC-Pkd1 KO model permits analysis of the pathophysiology of progressive cyst formation and associated renal insufficiency, as well as evaluation of the effect of therapeutic intervention. Another potential benefit is the mean lifespan of 8.2 weeks; this facilitates obtaining mortality data in a reasonably short time. Hence, on balance, the PC-Pkd1 KO model should prove useful for further study of ADPKD and drug intervention.

In conclusion, two viable, kidney-specific mouse models of ADPKD were created. Principal cells are the major cell type leading to cyst formation in the CD, while the paucity of cyst formation in IC-Pkd1 KO mice suggests that this cell type does not play a significant role in the pathogenesis of renal cyst formation. The lack of cyst formation in IC-Pkd1 KO is of particular interest in that these cells express cilia - it remains to be determined whether they express polycystin-1. The lack of papillary cyst formation suggests a strong temporal relationship between the timing of polycystin-1 disruption and cyst development. Finally, the PC-Pkd1 KO model is a viable model that should be useful for the further study of ADPKD and for testing therapeutic interventions.

METHODS

Generation of PC-Pkd1 KO mice

PC-specific knockout (KO) mice were generated in a manner similar to that previously described.21–23, 40 Floxed Pkd1 mice (Pkd1cond) have loxP sites flanking exons 1 and 4 of the Pkd1 gene, permitting selective deletion of essential coding regions on exposure to Cre recombinase.41 Mice were bred to obtain homozygotes for the Pkd1cond allele; these were bred with AQP2-Cre mice with PC-specific expression of Cre recombinase. AQP2-Cre mice contain a transgene with 11 kb of the mouse AQP2 gene 5′ flanking region driving expression of Cre recombinase. The AQP2-Cre mice are identical to those fully characterized in previous publications by our group21–23 and as used in collaboration with other investigators.40, 42 Female AQP2-Cre mice were mated with male Pkd1cond mice; female offspring heterozygous for both AQP2-Cre and floxed Pkd1cond were bred with males homozygous for Pkd1cond. Animals homozygous for Pkd1cond and heterozygous for AQP2-Cre (PC-Pkd1 KO) were used. Males containing the AQP2-Cre transgene were not used because AQP2 is expressed in sperm and causes recombination in fertilized oocytes. Offspring of the other possible genotypes that did not have Cre-mediated recombination served as the comparison group for the PC-Pkd1 KO animals.

Generation of IC-Pkd1 KO mice

IC-specific KO mice were generated using the Pkd1cond mice described above. Homozygous Pkd1cond mice were bred with B1-Cre mice with Cre recombinase selectively expressed in IC.25 B1-Cre mice contain a transgene with 7 kb of the mouse V-ATPase B1 subunit promoter driving Cre recombinase and an SV40 polyA tail; the B1-Cre mice have been extensively characterized and confer complete IC-specific knockout (all ICs undergo recombination) of the target gene as assessed using ROSA26-YFP reporter mice.25 The breeding strategy to obtain IC-Pkd1 KO mice and controls was as described above.

Genotyping

Tail genomic DNA was PCR amplified for the AQP2-Cre transgene and the B1-Cre transgene using oligonucleotide primers that amplify a region within Cre: CreF (5′-CAT TAC CGG TCG ATG CAA CGA G-3′) and CreR (5′-TGC CCC TGT TTC ACT ATC CAG G-3′). DNA was PCR amplified for the Pkd1cond and Pkd1wt alleles using primers GerF2 (5′-GGC TAT AGG ACA GGG ATG ACA T-3′) and GerR6 (5′-CAT ATT CCT CAC CTG GGA ACA G-3′). The amplified product of the Pkd1cond allele is 34 base pairs longer than the wild type allele, corresponding to the loxP site in intron 4.

Survival and BUN

PC-Pkd1 and IC-Pkd1 KO mice and littermate controls were allowed to survive to determine lifespan. Blood was collected from animals by cardiac puncture or from tail biopsy at times. Serum urea concentration was measured (BioAssay Systems, Hayward, CA) and the blood urea nitrogen (BUN) in mg/dl calculated by dividing the urea by 2.14.

Real time PCR for polycystin-1 mRNA in papilla and outer medulla

Papilla and outer medulla were dissected from wild type mouse kidney. Inner medullary collecting ducts were isolated from papilla as previously described.43 RNA was isolated using the Chomczynski method44 and reverse transcribed to cDNA using SuperScript II (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Pkd1 was amplified using Pkd1 F1 (5-CGC CAG TGG TCT GTT TTT G–3′) and Pkd1 R1 (5′-ACG GGC CAT GTT GTA GAG AG–3′) intron spanning primers on a Smart Cycler System (Cepheid, Sunnyvale, CA).

Histology

PC-Pkd1 KO and IC-Pkd1 KO mice and littermate controls were sacrificed at varying ages. For histology, kidneys were fixed in 10% normal buffered formalin, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned sagitally to obtain all layers of the kidney in a single section. Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin.

Immunohistochemistry

To show collecting duct origin of cysts in PC-Pkd1 KO animals, frozen sections were blocked with streptavidin/biotin blocking kit, incubated with biotinylated Dolichos biflorus agglutinin (DBA) followed by horseradish peroxidase streptavidin, developed using 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB), and counterstained with hematoxylin (all reagents from Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA).

Immunofluorescence

To determine the pattern of AQP2 expression in cysts, deparaffinized sections were incubated with anti-AQP2 goat polyclonal IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA) followed by Alexa Fluor 555 donkey anti-goat IgG (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). To determine the distribution and number of intercalated cells in the collecting duct, deparaffinized sections were incubated with a polyclonal rabbit antiserum to the V-ATPase B1subunit 45 followed by goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to CY3. The number and distribution of intercalated cells were further determined by breeding B1-Cre mice with reporter mice transgenic for ROSA26 promoter-loxP-stop-loxP-YFP 25. The loxP sequences undergo recombination in the presence of Cre, excising the stop sequence, and permitting YFP (yellow fluorescent protein) expression. Hence, cells which are yellow represent cells that express the B1 promoter. In both the V-ATPase B1 subunit staining and the B1-Cre mediated YFP expression, collecting ducts are readily identified. Total collecting duct cells and the number immunostained or yellow cells were counted (10 sections per kidney in 5 kidneys).

Western blotting for AQP2

Mouse kidneys were homogenized in 300 μM sucrose, 10 mM triethanolamine, 1 mM EDTA, and Roche complete protease inhibitors (pH 7.2). The samples were spun at 4000g for 10 min at 4°C, the supernatant centrifuged for 50 min at 17,000g at 4°C, and the final pellet resuspended in homogenization buffer. Protein concentration was determined using the BCA protein determination kit. Samples were run on a denaturing NUPAGE 4–12% Bis Tris mini gel, proteins transferred to a nylon membrane, the membrane incubated with the rabbit AQP2 primary antibody used in immunofluorescence studies, incubated with a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody, and visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence detection system. The membrane was stripped and re-probed using a rabbit β-actin antibody for loading normalization.

Cyclic AMP (cAMP) assay. Mouse kidneys were snap frozen and ground to a fine powder in liquid nitrogen, then homogenized in cold 5% tricarboxylic acid. An aliquot was removed for protein determination and the remainder was centrifuged at 600g for 10 minutes at 4°C. The supernatant was extracted with 3 volumes of water-saturated ether, the aqueous extract dried, reconstituted in cAMP assay buffer, and assayed directly in a cyclic AMP enzyme immunoassay using the manufacturer’s protocol (Assay Design, Ann Arbor, MI).

Magnetic Resonance Images

High-resolution MRI were obtained from ex vivo whole kidney on a 7.0 T scanner (BioSpec 70/30, Bruker BioSpin Co., Billerica, MA) using a 7.0 cm-diameter volume transmit and 1.0 cm-diameter surface receive radiofrequency coils. For each specimen, two sets of 3D images (256 × 128 × 128 matrix size at 100 μm isotropic spatial resolution) were obtained using standard rapid acquisition with relaxation enhancement sequence, including a fluid-attenuated inversion-recovery (600 ms inversion time, 800 ms time-to-repetition, 7.3 ms effective time-to-echo, and echo-train-length of 4) image, and a proton-density (2000 ms time-to-repetition, 7.3 ms time-to-echo, and echo-train-length of 8) image. The total scan time for the images was approximately 2 hr.

Statistics

Data on genotype were compared by Chi-square. Comparisons between KOs and their respective controls for BUN, kidney weight, and body weight were done by one way analysis of variance with the Bonferroni correction. Comparisons between PC-Pkd1 KO and controls for cAMP and AQP2 levels were done by the student’s t-test. P<0.05 was taken as significant. Data are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean.

Animal use

All animal experiments were ethically approved by the University of Utah Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIH grants DK69392 (to D.E.K.) and DK48006 (to G.G.G.); and by AHA grant 0725280Y (to K.L.R.). The Bruker BioSpec 70/30 MRI scanner used in the current study was funded in part by a grant (1 S10 RR023017) from NIH NCRR. Dr. Germino is the Irving Blum Scholar of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

None.

References

- 1.Huseman R, Grady A, Welling D, et al. Macropuncture study of polycystic disease in adult human kidneys. Kidney Int. 1980;18:375–385. doi: 10.1038/ki.1980.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bachinsky DR, Sabolic I, Emmanouel DS, et al. Water channel expression in human ADPKD kidneys. Am J Physiol. 1995;268:F398–F403. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1995.268.3.F398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hayashi M, Yamaji Y, Monkawa T, et al. Expression and localization of the water channels in human autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Nephron. 1997;75:321–326. doi: 10.1159/000189556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kovacs J, Zilahy M, Gomba S. Morphology of cystic renal lesions. Lectin and immuno-histochemical study. Acta Chir Hung. 1997;36:176–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yoder BK, Mulroy S, Eustace H, et al. Molecular pathogenesis of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2006;8:1–22. doi: 10.1017/S1462399406010362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Consortium TEPKD. The polycystic kidney disease 1 gene encodes a 14 kb transcript and lies within a duplicated region on chromosome 16. Cell. 1994;77:881–894. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90137-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mochizuki T, Wu G, Hayashi T, et al. PKD2, a gene for polycystic kidney disease that encodes an integral membrane protein. Science. 1996;272:1339–1342. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5266.1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yoder BK, Hou X, Guay-Woodford LM. The polycystic kidney disease proteins, polycystin-1, polycystin-2, polaris, and cystin, are co-localized in renal cilia. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:2508–2516. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000029587.47950.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Latta H, Maunsbach AB, Madden SC. Cilia in different segments of the rat nephron. J Biophys Biochem Cytol. 1961;11:248–252. doi: 10.1083/jcb.11.1.248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clapp WL, Madsen KM, Verlander JW, et al. Morphologic heterogeneity along the rat inner medullary collecting duct. Lab Invest. 1989;60:219–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shibazaki S, Yu Z, Nishio S, et al. Cyst formation and activation of the extracellular regulated kinase pathway after kidney specific inactivation of Pkd1. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:1505–1516. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guay-Woodford LM. Murine models of polycystic kidney disease: molecular and therapeutic insights. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2003;285:F1034–1049. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00195.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boulter C, Mulroy S, Webb S, et al. Cardiovascular, skeletal, and renal defects in mice with a targeted disruption of the Pkd1 gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:12174–12179. doi: 10.1073/pnas.211191098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim K, Drummond I, Ibraghimov-Beskrovnaya O, et al. Polycystin 1 is required for the structural integrity of blood vessels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:1731–1736. doi: 10.1073/pnas.040550097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lu W, Peissel B, Babakhanlou H, et al. Perinatal lethality with kidney and pancreas defects in mice with a targetted Pkd1 mutation. Nat Genet. 1997;17:179–181. doi: 10.1038/ng1097-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lu W, Shen X, Pavlova A, et al. Comparison of Pkd1-targeted mutants reveals that loss of polycystin-1 causes cystogenesis and bone defects. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:2385–2396. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.21.2385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Muto S, Aiba A, Saito Y, et al. Pioglitazone improves the phenotype and molecular defects of a targeted Pkd1 mutant. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:1731–1742. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.15.1731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu G, D’Agati V, Cai Y, et al. Somatic inactivation of Pkd2 results in polycystic kidney disease. Cell. 1998;93:177–188. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81570-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Starremans PG, Li X, Finnerty PE, et al. A mouse model for polycystic kidney disease through a somatic in-frame deletion in the 5′ end of Pkd1. Kidney Int. 2008;73:1394–1405. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lantinga-van Leeuwen IS, Leonhard WN, van der Wal A, et al. Kidney-specific inactivation of the Pkd1 gene induces rapid cyst formation in developing kidneys and a slow onset of disease in adult mice. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:3188–3196. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ahn D, Ge Y, Stricklett PK, et al. Collecting duct-specific knockout of endothelin-1 causes hypertension and sodium retention. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:504–511. doi: 10.1172/JCI21064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ge Y, Bagnall A, Stricklett PK, et al. Collecting duct-specific knockout of the endothelin B receptor causes hypertension and sodium retention. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2006;291:F1274–1280. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00190.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ge Y, Stricklett PK, Hughes AK, et al. Collecting duct-specific knockout of the endothelin A receptor alters renal vasopressin responsiveness, but not sodium excretion or blood pressure. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2005;289:F692–698. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00100.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nelson R, Stricklett P, Ausiello D, et al. Expression of a Cre recombinase transgene by the aquaporin-2 promoter in kidney and male reproductive system of transgenic mice. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:C216–C226. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.275.1.C216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller R, Lucero O, Riemondy K. V-ATPase B1-subunit promoter drives expression of Cre-Recombinase in intercalated cells of the kidney. Kidney Int. 2008 doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.569. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Teng-umnuay P, Verlander JW, Yuan W, et al. Identification of distinct subpopulations of intercalated cells in the mouse collecting duct. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1996;7:260–274. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V72260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jiang ST, Chiou YY, Wang E, et al. Defining a link with autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease in mice with congenitally low expression of Pkd1. Am J Pathol. 2006;168:205–220. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zharkikh L, Zhu X, Stricklett PK, et al. Renal principal cell-specific expression of green fluorescent protein in transgenic mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2002;283:F1351–1364. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.0224.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nauli SM, Kawanabe Y, Kaminski JJ, et al. Endothelial cilia are fluid shear sensors that regulate calcium signaling and nitric oxide production through polycystin-1. Circulation. 2008;117:1161–1171. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.710111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Natoli TA, Gareski TC, Dackowski WR, et al. Pkd1 and Nek8 mutations affect cell-cell adhesion and cilia in cysts formed in kidney organ cultures. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2008;294:F73–83. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00362.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nauli SM, Rossetti S, Kolb RJ, et al. Loss of polycystin-1 in human cyst-lining epithelia leads to ciliary dysfunction. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:1015–1025. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005080830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xu C, Rossetti S, Jiang L, et al. Human ADPKD primary cyst epithelial cells with a novel, single codon deletion in the PKD1 gene exhibit defective ciliary polycystin localization and loss of flow-induced Ca2+ signaling. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007;292:F930–945. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00285.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barr MM, Sternberg PW. A polycystic kidney-disease gene homologue required for male mating behaviour in C. elegans. Nature. 1999;401:386–389. doi: 10.1038/43913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nauli S, Alenghat F, Luo Y, et al. Polycystins 1 and 2 mediate mechanosensation in the primar cilium of kidney cells. Nature Genetics. 2003;33:129–137. doi: 10.1038/ng1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang X, Wu Y, Ward CJ, et al. Vasopressin directly regulates cyst growth in polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:102–108. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007060688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Belibi FA, Reif G, Wallace DP, et al. Cyclic AMP promotes growth and secretion in human polycystic kidney epithelial cells. Kidney Int. 2004;66:964–973. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00843.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gattone VH, 2nd, Wang X, Harris PC, et al. Inhibition of renal cystic disease development and progression by a vasopressin V2 receptor antagonist. Nat Med. 2003;9:1323–1326. doi: 10.1038/nm935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yamaguchi T, Nagao S, Kasahara M, et al. Renal accumulation and excretion of cyclic adenosine monophosphate in a murine model of slowly progressive polycystic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 1997;30:703–709. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(97)90496-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wilson PD, Goilav B. Cystic disease of the kidney. Annu Rev Pathol. 2007;2:341–368. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.2.010506.091850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guan Y, Hao C, Cha DR, et al. Thiazolidinediones expand body fluid volume through PPARgamma stimulation of ENaC-mediated renal salt absorption. Nat Med. 2005;11:861–866. doi: 10.1038/nm1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Piontek KB, Huso DL, Grinberg A, et al. A functional floxed allele of Pkd1 that can be conditionally inactivated in vivo. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15:3035–3043. doi: 10.1097/01.ASN.0000144204.01352.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang H, Zhang A, Kohan DE, et al. Collecting duct-specific deletion of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma blocks thiazolidinedione-induced fluid retention. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:9406–9411. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501744102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kohan DE, Padilla E, Hughes AK. Endothelin B receptor mediates ET-1 effects on cAMP and PGE2 accumulation in rat IMCD. Am J Physiol. 1993;265:F670–F676. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1993.265.5.F670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. Single step RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem. 1987;162:156–159. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Miller RL, Zhang P, Smith M, et al. V-ATPase B1-subunit promoter drives expression of EGFP in intercalated cells of kidney, clear cells of epididymis and airway cells of lung in transgenic mice. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2005;288:C1134–1144. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00084.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]