Abstract

To move forward with immunotherapy it is important to understand how the tumor microenvironment generates systemic immunosuppression in patients with renal cell carcinoma (RCC) as well as in patients with other types of solid tumors. Even though antigen discovery in RCC has lagged behind melanoma, recent clinical trials have finally authenticated that RCC is susceptible to vaccine-based therapy. Furthermore, judicious coadministration of cytokines and chemotherapy can potentiate therapeutic responses to vaccine in RCC and prolong survival, as has already proved possible for melanoma. While high dose interleukin-2 immunotherapy has been superseded as first line therapy for RCC by promiscuous receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors (rTKI) such as sunitinib, sunitinib itself is a potent immunoadjunct in animal tumor models. A reasonable therapeutic goal is to unite anti-angiogenic strategies with immunotherapy as first line therapy for RCC. This strategy is equally appropriate for testing in all solid tumors in which the microenvironment generates immunosuppression. A common element of RCC, pancreatic, colon, breast and other solid tumors is large numbers of circulating myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSC), and because MDSC elicit regulatory T cells rather than vice versa, gaining control over MDSC is an important initial step in any immunotherapy. While rTKI like sunitinib have a remarkable capacity to deplete MDSC and restore normal T cell function in peripheral body compartments such as the bloodstream and the spleen, such rTKI are only effective against MDSC which are engaged in phosphoSTAT3-dependent programming (pSTAT3+). Unfortunately, rTKI-resistant pSTAT3- MDSC are especially apt to arise within the tumor microenvironment itself, necessitating strategies which do not rely exclusively upon STAT3 disruption. The most utilitarian strategy to gain control of both pSTAT3+ and pSTAT3- MDSC may be to exploit the natural differentiation pathway which permits MDSC to mature into tumoricidal macrophages (TM1) via such stimuli as TLR agonists, IFN-γ and CD40 ligation. Overall, this review highlights the mechanisms of immune suppression employed by the different regulatory cell types operative in RCC as well as other tumors. It also describes the different therapeutic strategies to overcome the suppressive nature of the tumor microenvironment.

Keywords: renal cell carcinoma, kidney cancer, immunosuppression, tumor microenvironment, myeloid-derived suppressor cells, tumor-associated macrophages, Tregs, dendritic cells, STAT3, STAT5

A. Introduction

The clear cell variant of renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is the most common form of kidney cancer in humans, and shares with melanoma a unique potential to respond dramatically to immunotherapy (1-3). Typically, however, less than 15% of all RCC patients experience therapeutically enduring responses from high dose interleukin-2, the gold standard of immunotherapy, and the overall survival of all RCC patients receiving IL-2 is only one year (1-3). In contrast, recent efforts to target angiogenesis pathways in RCC have increased the response rate to 40% and overall survival to 40 months (4). This unprecedented therapeutic advance quickly caused targeted therapy to supplant high dose IL-2 as first line therapy for RCC, both in community practice and at most academic centers.

Ironically, given the importance of blood supply to every solid tumor, the response rate of common human cancer types to targeted antiangiogenic therapy has been surprisingly modest, except for RCC. RCC's disproportionately greater susceptibility may reflect the unique roles played by several genes such as Von Hippel Landau (VHL) and hypoxia-inducing factor 1 alpha (HIF1α) in regulating RCC angiogenesis, both in inherited and sporadic cases of RCC (5). Nonetheless, even when RCC is the target, the most effective “antiangiogenic” agents are highly promiscuous receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors (rTKI) such as sunitinib and sorafenib, which simultaneously block signal transduction for a multitude of factors including vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), stem cell factor (SCF, for which c-kit is receptor), CSR (colony stimulating factor) and Flt3L (Flt3 ligand) (5-7). In contrast, narrower spectrum rTKI which merely target VEGF receptors, for example, are as ineffective against RCC as they are against other common types of solid human tumors. The requirement for promiscuity suggests that effective targeting of RCC and other solid tumors with rTKI extends far beyond the mere targeting of angiogenesis.

Coincidentally, the promiscuous rTKI which have proved effective against human RCC also have profound impacts upon the immune system (8,9). For example, the promiscuous rTKI sunitinib causes pronounced depletion of peripheral blood myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSC), thereby restoring normal T cell function within that compartment. The even more promiscuous rTKI sorafenib similarly depletes peripheral MDSC, but also itself interferes with normal T cell function (9). While it is tempting to use these observations to explain sunitinib's therapeutic superiority to sorafenib in RCC, it is futile, because even RCC patients whose tumors progress rapidly during sunitinib therapy display dramatic MDSC depletion and normalized T cell function within their peripheral blood (9,10, 25). A similar disparity is observed in mouse tumor models, where MDSC depletion and normalized T cell function are uniformly observed in the spleen during sunitinib treatment regardless of whether tumors themselves simultaneously progress or regress (9,10).

In-depth investigations are providing the explanation for this seeming paradox: whereas sunitinib profoundly depletes MDSC in both peripheral human blood and mouse spleen, normalizing T cell function in these roughly equivalent peripheral compartments, sunitinib's depletion of intratumoral MDSC is often less decisive (9,10). The recognition that sunitinib mainly disrupts STAT3-dependent functions has given rise to the testable hypothesis that peripheral MDSC engage predominantly in STAT3-dependent programming, whereas factors preferentially produced in the tumor microenvironment diversify intratumoral MDSC to engage in non STAT3-dependent activities which are sunitinib-resistant. Understanding and combatting such resistance mechanisms may enable agents like sunitinib to decisively immunomodulate the tumor microenvironment, further improving therapeutic efficacy against all types of solid tumors.

We first discuss the host inhibitory cells which arise bodywide as a consequence of factors generated or induced by the tumor microenvironment (MDSC, tumor-associated macrophages (TAM) and regulatory T cells (Tregs)). This is followed by considerations of chemokines and chemokine receptors which define the relationship of these host inhibitory cells to the host environments, both intratumoral and extratumoral compartments. We conclude with considerations of how the effector immune system functions under this adversity. Therapeutic strategies to overcome the challenge of the tumor microenvironment are discussed continuously.

B. Pathological generation of inhibitory immune cells as a consequence of the RCC microenvironment

B.1. Myeloid-derived Suppressor Cells (MDSC )

B.1.a Characterization

Myeloid-derived suppressor cells represent a heterogenous cell population with immunosuppressive and angiogenic properties. While they are actually normal host cells of bone marrow origin, systemic signals generated by pathologic conditions such as cancer cause them to leave bone marrow prematurely to engage in continuing proliferation and premature activation at extramedullary locations. In mouse tumor models, MDSC infiltrate blood, normal peripheral organs and tumors themselves, displaying persistent immature elements of monocyte (M-MDSC) and neutrophil (G-MDSC) morphology (11). These cells are functionally defined by their capacity to suppress T cell immunity through a variety of mechanisms (11,12). MDSC can deplete nutrients necessary for T cell function such as L-arginine (13) via arginase-1 activity. They can consume L-cysteine, thereby limiting the availability of this amino acid which is necessary for lymphocyte activation (14). These types of T cell inhibition are rapidly reversible by depleting MDSC or by restoring the missing nutrients. However, some MDSC activation states result in production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and/or inducible nitric oxide synthase, resulting in a less reversible loss of both CTL activity and IFN-γ production, and even destruction of the effector T cell response (9,10,15,16). As demonstrated in animal tumor models, MDSC can employ tyrosine nitration to sterically block MHC-bound peptides from being presented to T cells via the TCR-CD8 complex (17). MDSC can also inhibit T cell function indirectly by promoting expansion of regulatory T cells (Treg) and by inducing conversion of naïve T cells to a Tregs phenotype (18,19). Finally, MDSC can also decrease the L-selectin expression of naïve T cells, eliminating their proclivity to enter peripheral lymph nodes where dendritic cell (DC)-mediated sensitization to upstream tumor Ags may predominantly take place (20). (Figure 1, Table 1)

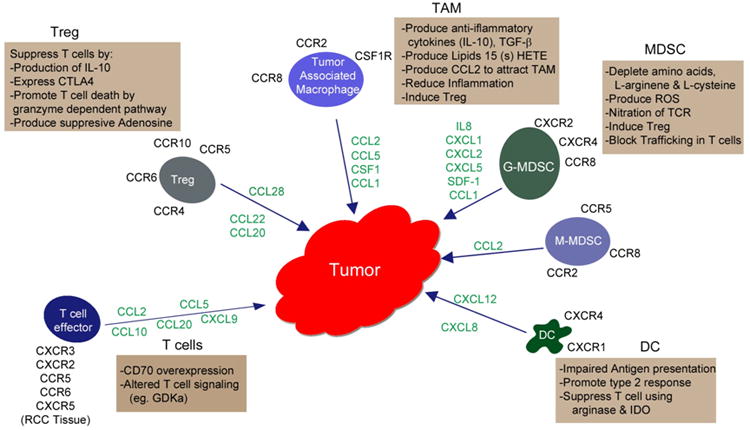

Figure 1.

The production of chemokines by tumor and stromal cells and their subsequent binding to chemokine receptors expressed by different immune cells results in the activation and trafficking of these cells into renal tumor tissue initiating events that typically promote tumor progression rather than antitumor immunity. Listed are the various immune regulatory cell types infiltrating the tumor along with the different mechanisms they may utilize, alone or in combination, to impair T cell function and/or promote angiogenesis. Also shown are the infiltrating effector T cells along with possible mechanisms that may lead to T cell anergy.

Table 1.

| Suppression in Tumors | Targets to Prevent/ Reverse Suppression |

|---|---|

| MDSC (Myeloid Derived Suppressor Cells) | Promote differentiation to DC (ATRA) |

| Convert to tumoricidal macrophages (CD40 ligand or agonal antibodies, TLR agonists or Type 1 Cytokines) | |

| Block suppressive Activity with: Synthetic triterepoids and PDE-S inhibitors | |

| Reduce MDSC numbers (Sunitinib, Gemeitabine, 5-FU) | |

| Antagonist or antibody block chemokine receptors, CXCR2, CCR2 & CXCR4 | |

| TAM (Tumor associated macrophages) | Inhibit lipoxygenase pathway (NOGA) |

| Inhibitor of M-CSFR | |

| Treg (T regulatory cells) | IL2R via CD25 antibody, OnTAK |

| Cyclosphamide/Paclitaxel | |

| Sunitinib reduces the number of cells | |

| Block/antagonize chemokine receptors |

In addition to displaying overt immunosuppressive activity, MDSC can promote angiogenesis. The co-injection of MDSC (CD11b+Gr1+) along with tumor cells into mice increased vascular density and maturation within the tumor that was dependent on production of metallomatrix protein 9 (MMP9). MDSC were shown to become incorporated into tumor endothelium and to acquire features of endothelial cells (21). In certain mouse tumor models such as RENCA and B16, STAT3 signaling is thought to play a prominent role in promoting the angiogenic activity of tumor-infiltrating MDSC and macrophages, and in these circumstances production of angiogenic proteins such as VEGF and bFGF has been shown to be STAT3- dependent. These STAT3 regulated molecules in turn induce constitutive activation of STAT3 in endothelial cells, thereby further promoting angiogenesis in a manner which can be blocked by STAT3 inhibitors (22).

Multiple populations of MDSC have been defined in human tumors by immunostaining and FACS analysis (12). Normally granulocytic (CD33+HLADR-CD15+CD14-), monocytic (CD33+HLADR-CD15-CD14+) and lineage negative (CD33+HLADR-CD15-CD14-) subsets predominate, although additional subsets have been identified. In RCC patients, six populations of MDSC have been defined (23). However, in RCC patients (13,24-26) as well as in other tumors such as brain, lung, head and neck and pancreatic cancer (28,33), G-(granulocytic) MDSC represent the numerically prevalent population. G-MDSC isolated from RCC patients mediate T cell suppression mainly by increased production of arginase, resulting in the depletion of arginine in patient plasma and downregulation of the zeta chain in T cells (13,24,26). This type of T cell inhibition is very efficient but also rapidly reversible by depleting the G-MDSC or by restoring the provision of arginine.

In early studies of mouse MDSC, available evidence suggested that phenotypic immaturity was absolutely required for suppressor function (27,29). Contradicting this dogma, human studies have readily demonstrated that mature myeloid-derived cells can also display canonical MDSC function. For example, in RCC patients, peripheral blood was found to contain already mature, activated neutrophils with arginase-promoting suppressive activity, appropriately characterized as G-MDSC (13,24). These findings resonate with work of Schmielau and Finn showing that a significant proportion of granulocytes from pancreatic, colon and breast cancer patients have lower than usual density, causing them to co-migrate with lymphocytes and monocytes into the Ficoll-Hypaque™ interface during peripheral blood centrifugation rather than into the cell pellet with red blood cells (30). The presence of such density-reduced granulocytes in these patients correlated with reduced T cell zeta-chain expression and decreased cytokine production; in short, they too likely represented G-MDSC. Their reduced density most likely derives from the continuous unloading of cytoplasmic granules, as opposed to the granule retention of normal resting neutrophils. A similar reduction in granulocyte density with acquisition of suppressive functions was also achieved in healthy donors by treating mature resting granulocytes with the chemotactic peptide N-formyl-L-methionyl-L-leucyl–L-phenyalanine (fmlp) (30). Other data, however, suggest that at least a portion of human G-MDSC constitute immature neutrophils (CD16-CD33+HLADR-CD66b+) since they display low to absent expression of the neutrophil maturation marker CD16 (FcRγ1) (31). Additional functional and gene array studies are underway to define the interrelationship between the mature vs immature subsets of G-MDSC, patient neutrophils and resting vs activated neutrophils from healthy donors. Distinctive effects of cytokines in culture have already provided guiding insights; for example, it has been reported that immature G-MDSC have striking phenotypic similarities to the MDSC derived from human bone marrow after culture with GM-CSF and IL-6 (32). This latter study also showed that the transcription factor C/EBPb to be a potentially important regulator of MDSC -mediated immune suppression in cancer.

The abnormal expansion of G-MDSC and the other subsets in cancer patients is likely due to the overproduction of different growth factors including G-CSF, GM-CSF, IL-6, VEGF, S100, and SCF (11), while other products in the tumor microenvironment promote MDSC activation, including IFN-γ, COX2-dependent prostaglandins, IL-4, IL-13 and TGF-β. Which of these cytokines and growth factors may be consistently operative in RCC patients is not as yet well defined. The one exception is VEGF, since it is abundantly expressed in RCC as a result of the silencing of VHL (5). Additionally, G-MDSC accumulation in RCC patients may be partly attributable to the differentiation of M-MDSC into G-MDSC as a consequence of retinoblastoma gene silencing (33). GM-CSF and tumor conditioned medium (TCM) can also be used in vitro or in vivo to differentiate M-MDSC from tumor-bearing mice into G-MDSC. In contrast, monocytes from non-tumor bearers cannot be induced to differentiate into G-MDSC (33).

A correlation is apparent between MDSC levels in RCC patients' blood and tumor progression. Higher pretreatment levels of M-MDSC and G-MDSC in mRCC patients negatively correlates with overall survival (23). Moreover, peripheral blood neutrophil levels have been identified as an independent predictor for short overall survival in metastatic RCC patients (34-38). Similarly in RCC patients with localized rather than widely metastatic disease, intratumoral CD66b+ neutrophils were an independent prognostic factor associated with a short recurrence-free survival (39).

B.1.b Strategies to combat MDSC

A number of strategies are being tested to reduce MDSC numbers and/or function in mouse tumor models and in cancer patients as a means to reverse immunosuppression (reviewed in (11,40)). Strategies tested in RCC patients include forcing MDSC maturation, blockade of MDSC immunosuppressive effects, and MDSC depletion:

The use of all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA) to promote the differentiation of immature myeloid cells has shown promise. In vitro studies showed that ATRA reduced T-cell suppression which correlated with the differentiation of MDSC into normal myeloid cells (16). Treatment of RCC patients with ATRA significantly reduced MDSC numbers in the blood. This trend was associated with an improvement in the myeloid/lymphocyte DC ratio and was correlated with a significant increase in tetanus-toxoid-specific T-cell responses. However, combination treatment with IL-2 impaired the impact of ATRA on MDSC (41). The mechanism of MDSC differentiation by ATRA appears to be related to its ability to cause the accumulation of glutathione in these cells (42).

Alternative MDSC differentiation strategies include the exploitation of natural myeloid maturation pathways to convert MDSC into tumoricidal macrophages, which can be accomplished through signal transduction with CD40 ligand or agonal mAb, TLR agonists and/or T1-type cytokines (43-46).

Another strategy is to block suppressive MDSC function rather than reducing their numbers. In vitro studies showed that blocking the levels of reactive oxygen species with synthetic triterpenoid (CDDO, Me) via up-regulation of several antioxidant genes (NADPH:quinone oxidoreductase1, thioredoxin, catalase, superoxide dismutase) reduced the suppressive activity of MDSC isolated from patients with RCC and soft tissue sarcomas (47). Treatment of tumor-bearing mice with CDDO-Me did not alter the number of phenotypic MDSC in the spleens but did reduce their suppressive activity and decreased tumor growth.

A third strategy is to destroy MDSC so that they can no longer immunosuppress, and sunitinib is a seemingly promising candidate for this purpose. Treatment of RCC patients with sunitinib (current front line therapy) dramatically and consistently reduces the number of MDSC in the peripheral blood (26,48), thereby restoring Type-1 T cell IFN-γ responses (26)(49). In contrast to sunitinib, the anti-VEGF monoclonal antibody (mAb) bevacizumab did not reduce MDSC in peripheral blood, suggesting that neutralization of VEGF signaling by itself is insufficiently promiscuous to reduce MDSC (13).

In certain mouse tumor models administration of sunitinib in addition to vaccines and/or adoptive therapy can enhance tumor regression, improve survival and increase development of antitumor T cell responses compared to either treatment alone (50-53). This confirms sunitinib's value as an immunoadjunct, but does not answer whether single agent sunitinib's immunomodulations themselves constitute effective immunotherapy. As noted above, virtually all RCC patients receiving sunitinib display a dramatic reduction in peripheral blood MDSC as well as normalization of peripheral blood T cell secretion of IFN-γ and proliferation during in vitro polyclonal stimulation. Paradoxically, these striking peripheral blood immunomodulations occur whether the RCC patients' tumors regress or progress during sunitinib treatment, hence the immunomodulations are nonpredictive of sunitinib's therapeutic efficacy. Similarly, sunitinib's consistent ability to deplete peripheral blood MDSC is not predictive of the drug's ability to deplete intratumoral MDSC, which is contrast is “hit or miss.” However, sunitinib's ability to deplete intratumoral MDSC is predictive of the therapeutic response to sunitinib, at least in animal tumor models.

B.1.3 Resistance to MDSC targeted therapy

Resistance to anti-VEGF mAb therapy and resistance to rTKI appear to consist of two non-overlapping escape mechanisms:

Resistance to anti-VEGF mAb therapy in tumor-bearing mice depends upon MDSC infiltration of tumor and the production of G-CSF, and such resistance can be alleviated in certain instances by anti-G-CSF mAb administration. Resistance can also require G-MDSC to produce the MDSC chemo-attractant Bv8, which can promote intratumor accumulation of MDSC independent of the VEGF signaling pathway (54). A recent study suggests that G-CSF mobilization of MDSC is regulated by a MEK-dependent mechanism, since inhibition of G-CSF by a MEK inhibitor restored tumor sensitivity to anti-VEGF therapy in a mouse tumor model (55). Whether MEK inhibitors can reverse resistance to anti-VEGF mAb therapy and sunitinib treatment in cancer patients will be of considerable interest.

- MDSC likely also contribute to the near complete resistance of the mouse 4T1 mammary tumor model to sunitinib, which stands in contrast to the RENCA kidney cancer model's near total susceptibility to sunitinib (25). Sunitinib therapy resulted in complete regressions of RENCA tumors but had only a modest and fleeting impact on 4T1 tumors before they progressed. These therapeutic disparities correlated with the persistent survival of MDSC within 4T1 tumors versus a sustained wipeout of intratumoral MDSC in the RENCA model which lasted until sunitinib was discontinued (25). Paradoxically, splenic MDSC were effectively wiped out by sunitinib in both the 4T1 and RENCA models (25). Many observations point to a 4T1 escape mechanism in which GM-CSF produced intratumorally induces local MDSC to switch from sunitinib-sensitive STAT3-dependent programming to sunitinib-resistant STAT5-dependent programming:

- GM-CSF is detectable intratumorally but not intrasplenically in the 4T1 model (10).

- Exogenous GM-CSF can protect bone marrow-derived MDSC from sunitinib-induced cell death in vitro by substituting a STAT5-dependent, differentiation pathway for the sunitinib-susceptible, STAT3-dependent differentiation pathway (25,56). Knockout mouse studies have confirmed unequivocally that pSTAT5 confers sunitinib resistance (25).

- Systemic administration of anti-GMCSF (neutralizing) mAb in addition to sunitinib better retards 4T1 tumor growth, enhances the frequency of intratumoral T cells and decreases the frequency and absolute numbers of intratumoral MDSC (Figure 2).

- In contrast, systemic administration of recombinant GMCSF causes intrasplenic MDSC in the 4T1 model to develop sunitinib resistance similar to that already observed intratumorally (the compartment in which GM-CSF is naturally produced) (25).

- Real time analyses of activated STAT proteins in 4T1-bearing mice have confirmed that intrasplenic MDSC display uniform activation only of STAT3, predictive of sunitinib sensitivity (22,52,57,58). In contrast, intratumoral MDSC variably activate STAT3, STAT1 and/or STAT5, or exist without any detectable STAT activation, affording alternatives to STAT3-dependent programming which are resistant to sunitinib (59). These observations strongly suggest that sunitinib treatment can only be effective for ablating MDSC in those body compartments where prevalent cytokines favor STAT3-dependent differentiation (e.g., G-CSF and IL-6 are the likely prevalent cytokines within the spleen). In contrast, compartments in which prevalent cytokines promote alternatives to STAT3-dependent differentiation (e.g., GM-CSF and IFN-γ within the tumor bed promote STAT5- and STAT1-dependence respectively) have a ready basis for the MDSC displaying sunitinib resistance.

Figure 2.

Neutralization of host GM-CSF potentiates responsiveness of 4T1 tumors to sunitinib. BALB/c mice bearing 10 day s.c. syngeneic 4T1 tumors were treated twice daily with 1 mg sunitinib (“Sunitinib” “Sun” or “Sutent” 50 mg/kg) for 9 days, and variously also received 1 gm anti-GMCSF mAb or isotype control mAb i.p. weekly from day 0 of tumor challenge. Mice were sacrificed on day 20 and tumors analyzed for content of MDSCs and T cells. Bar graphs shows frequency or absolute numbers of MDSC, CD4 and CD8 cells intratumorally. Anti-GMCSF but not ctrl IgG reduced MDSC frequency in conjunction with sunitinib treatment and preserved intratumoral T cells compared to sunitinib treated or sunitinib+Ctrl IgG mice. Line graph shows significant retardation of 4T1 progression for sunitinib+anti-GMCSF therapy vs untreated mice, whereas no significant difference for sunitinib or sunitinib+Ctrl IgG mice vs untreated.

B.2 Tumor-Associated Macrophages

Macrophages acquire distinctive tissue specific phenotypes that are influenced by the tissues in which they reside (60). The two extreme functional forms of macrophages are the classic M1 and M2 phenotypes. but it is now recognized that multiple variations of the M1/M2 phenotype exist (60). The M1 phenotype occurs when macrophages are activated by combinations of toll-like receptor agonists and type-1 cytokines such as IFN-γ. The functional hallmarks of M1 cells include the heightened ability to phagocytize pathogens, produce proinflammatory cytokines (IL-12, TNFa) present class II-restricted antigens, and kill tumor targets (61,62). In contrast, tumor associated macrophages (TAM) typically have an M2-like phenotype induced by type-2 cytokines (IL-4, IL-13), and display higher production of anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10. They also up-regulate molecules that can inhibit the development of adaptive immune responses, promote wound repair and reduce inflammation (63).

Several studies have identified a dominance of TAM in patients with clear cell RCC. In one study TAM were characterized as macrophages (CD11b+HLA-DR+CD15-CD33-CD163+CD68+) with, however, distinctive negativity for CD33 (64). These cells displayed immunosuppressive properties, including TAM production of IL-10, along with the additional ability to enhance T cell production of IL-10 (64). Isolated TAM as well as tumor tissue produced significant levels of the chemokine CCL2 (MCP-1) that attracts additional monocytes to the tumor. The production of IL-10 and CCL2 by RCC TAM appears to be mediated by overexpression of the enzyme 15-lipoxygenase-2 (15-LOX2), resulting in substantial production of the biologically active lipid 15 (S) HETE. Interestingly, inhibition of the lipoxygenase pathway by the inhibitor NDGA caused a reduction in CCL2 expression by TAM, along with a diminished capacity of these cells to produce IL-10 and to induce T cell mediated production of IL-10 in co-culture experiments. Additionally, co-incubation of TAM with T cells increased lymphocyte expression of CTLA-4 and Foxp3, thereby providing another mechanism of tumor escape initiated by TAM. However, this pathway of suppression was not regulated by 15-LOX2 (64).

Another study demonstrated that TAM in RCC expressed the surface macrophage lineage markers CD163 and CD204 and that the frequency of intratumoral CD163+ cells increased with age, nuclear grade and TNM classification. In univariate analysis but not in multivariate analysis the level of CD163+ cells was significantly associated with poor clinical outcome (65). This study also showed that tumor-conditioned medium (TCM) from RCC lines promoted the polarization of macrophages to an M2 phenotype and that incubation of the TAM with cancer cell lines induced STAT3 activation in the malignant cells, thereby further promoting tumor survival and a suppressive phenotype. This cell-cell interaction between TAM and RCC malignant cells is likely mediated by membrane bound macrophage colony-stimulating factor (mM-CSF) expressed on renal tumors and M-CSFR expressed on macrophages; this hypothesized interaction is supported by the demonstration that reducing M-CSFR on macrophages with the use of an inhibitor also blocked STAT3 activation in tumor cells (65). Additionally, CSF-1 and CSF-1R can be co-expressed by RCCs and tubular epithelial cells (TECs) that are in close proximity to one another. CSF-1 engagement of CSF-1R enhanced RCC survival and proliferation and diminished apoptosis. Thus, a CSF-1-dependent autocrine pathway may also promote the growth of RCC, making the CSF-1/CSF-1R signaling pathway a rational therapeutic target for this tumor (66).

B.3 T-regulatory cells

Tregs (CD4+CD25+Foxp3+) are known to be important mediators of immune suppression in cancer patients, and in some tumor types the frequency of Tregs infiltrating tumors correlates with poor clinical outcome (67). Among two main types of Tregs, natural Tregs develop in the thymus and play a key role in self tolerance (67). Additionally, Tregs can be induced from T cells in the periphery in response to antigenic stimulation as a result of tolerogenic conditions (67,68). In contrast to CD25 and Foxp3, the IL-7R (CD127) is down regulated on Tregs (69). Additional markers are expressed which, although not exclusive to Tregs, help to define their suppressive mechanisms (70). These include GITR, a member of the TNFR superfamily which promotes suppressive activity as does CTLA-4, a costimulatory molecule with negative effects on T cell activation (71,72). CTLA-4 expressed on Tregs can reduce or block CD80 and CD86 upregulation on DC, thus preventing their co-stimulatory function and hindering T cell activation (73). Tregs can also meditate T cell suppression by production of IL-10 and TGF-β, although neutralization Ab studies suggest that these cytokines account for only a portion of Tregs' suppressive activity (70). Activated Tregs can also induce cell death in CD4+ and CD8+ effector T cells by a granzyme-dependent pathway. This mechanism of suppression is supported by the observation that Tregs from granzyme-B deficient mice show reduced suppressive activity (74,75). The accumulation of extracellular adenosine binding to receptors (A2A) on T cells also promotes lymphocyte suppression by Tregs that express CD39 (76,77). CD39 is an ectonucleotidase which in conjunction with CD73 induces cleavage of ADP and AMP, leading to the production of immunosuppressive adenosine that can block multiple T cell functions. Unlike murine Tregs, those from humans may express CD39 alone, relying on surrounding cells (endothelial cells) to express CD73 (70). (Figure 1, Table 1)

Multiple studies have shown that Tregs are increased in the peripheral blood of patients with RCC when compared to healthy donors (49,78-84). Higher numbers of Foxp3+ Tregs in the peripheral blood or tumor bed were predictive of shortened overall survival as well as shortened disease-free survival (79,81,83,85). Additionally, a significant positive correlation was observed between the frequency of tumor-infiltrating Tregs and VEGF protein expression, as well as between Tregs frequency and microvessel density score (80), suggesting that the level of Treg infiltrate correlated with angiogenic status. The frequency of tumor-infiltrating Tregs was also shown to significantly correlate with the pathological stage and nuclear grade (80).

Whereas the above reports underscored the poor prognosis associated with elevated levels of Foxp3+ Tregs, a single study by Siddiqui et al reported that patients with localized RCC experienced poorer survival if there was a higher frequency of tumor-infiltrating CD4+CD25+ T cells which were also negative rather than positive for Foxp3 (84). Such a Foxp3 negative suppressor T cell phenotype has been observed in type 1 regulatory CD4+ T cells (Tr1) which produce IL-10 and TGF-β in recognition of self-antigens, as well as in Th3 cells which produce TGF-β in oral tolerance responses (86,87).

Several studies in RCC patients demonstrated that treatment with high-dose IL-2 alone or with vaccine (composed of DC pulsed with RCC lysates) caused an increase in the number of Tregs within the peripheral blood. The expansion of Tregs was significantly lower in the responding patients versus the non-responders and in the responders there was an associated down-regulation of genes linked to Treg pathways (78,82,88). Likewise, analysis of core biopsies from RCC patients revealed that intratumoral Foxp3+ Treg numbers significantly increased during IL-2-based immunotherapy, and high numbers of on-treatment Foxp3+ cells were correlated with poor prognosis and poor response to treatment (85).

Given these findings, it is entirely appropriate that multiple strategies are being tested to reduce Tregs in cancer patients, including those with RCC. Targeting CD25 with Ab is effective at decreasing Tregs in mouse tumor models, resulting in tumor regression (89). The use of human anti-CD25 mAb in melanoma patients reduced circulating Tregs and promoted the expansion of tumor-specific CTL following vaccination (90). In metastatic RCC patients treatment with recombinant IL-2 diphtheria toxin conjugate DAB(389)IL-2 (AKA, denileukin, diftitox or ONTAK) was effective at eliminating CD25+ Tregs from the PBMCs without altering the levels of T cells expressing low or intermediate levels of CD25. When combined with a tumor RNA-transfected DC vaccine ONTAK improved the induction of a tumor-specific T cell response in RCC patients relative to treatment with vaccine alone (91). The main issue with targeting CD25 is that activated T cells also express CD25, and that reducing the number of tumor-specific T cells could diminish the anti-tumor T cell response.

Some chemotherapy agents such cyclosphamide and paclitaxel transiently reduce the number of Tregs in the peripheral blood (70). In a recent vaccine trial using multiple tumor associated peptides in mRCC patients it was revealed that a single dose of cyclophosphamide (300 mg/m2) reduced the number of Tregs and this reduction coincided with the presence of a T cell response to peptide vaccine and with longer patient survival (23).

Given that Tregs can express VEGFR2, which is a target of the rTKI sunitinib and sorafenib, it is not surprising these small molecules can reduce Treg levels in the peripheral blood (49,92,93). In one study a decrease in the number of Tregs after 2 or 3 cycles of sunitinib treatment (P<0.05) was associated with longer overall survival of mRCC patients. In the same study the intratumor levels of Tregs also decreased in 5/7 patients following sunitinib therapy in a neoadjuvant trial (92) suggesting that systemic treatment with sunitinib may reduce immune suppression in the tumor microenvironment as has been reported in mouse tumor models treated with sunitinib alone and in combination with immunotherapy (25,50-53). The reduction of Tregs by sunitinib may in fact be an indirect consequence of MDSC reduction (19,26,53). Interestingly, the induction of Treg expansion by MDSC is dependent on MDSC expression of CD40 (19). Blocking Treg function is another approach to reducing Treg numbers and this includes the use of anti-CTLA-4 and anti-PD-1 antibodies, since both proteins are expressed on Tregs. However, the main strategic goal of anti-CTLA-4 mAb therapy remains to block the interaction of CTLA-4 on effector T cells with CD80/CD86 on Ag-presenting cells, and there is some evidence that injudiciously dosed anti-CTLA-4 can paradoxically increase Treg numbers while failing to block their function (94,95).

C. Chemokine and chemokine receptor dysregulation in RCC

Chemokines and chemokine receptors are involved in tumor development in diverse ways that include roles in cell trafficking, tumor metastasis, tumor cell proliferation and neovascularization (96). Chemokine and chemokine receptors are critical for the migration of T effectors and M1 macrophages into the tumor to achieve therapeutic ends, but they also promote the accumulation of immunosuppressive cells within the tumor (96). Thus, a better understanding of chemokines and their receptors is important to develop strategies which may favorably control their expression and/or function within the tumor microenvironment. (Figure 1, Table 1).

C.1 MDSC

Limited studies have been performed to define the trafficking of G- and M-MDSC into tumors. Nevertheless, recent work has shown that impaired TGF-β signaling results in the recruitment of MDSC into murine tumors that is dependent on the chemokine/chemokine receptor axes SDF-1/CXCR4 and CXCL5/CXCR2 (97). CXCR2 and CXCR4 are expressed predominantly on G-MDSC while CCR5 and CCR2 are expressed mainly on M-MDSC. The CXCR2 antagonist SB-265610 selectively reduced the accumulation of the G-MDSC subset in the tumor indicating that CXCR2 is a major receptor in regulating G-MDSC migration. CXCR4 is expressed at high levels on tumor derived-MDSC compared to spleen-derived MDSC and in vitro studies showed that their migration towards its SDF-1 was blocked by neutralizing mAb to SDF-1, suggesting that this chemokine regulates trafficking of CXCR4+ MDSC (97). Interestingly, CXCR4 is overexpressed on human RCC as a result of loss-of-function of the VHL gene and the expression of CXCR4 predicts poor prognosis in RCC (98,99). These findings would make it difficult to target CXCR4 on MDSC in mRCC patients. Targeting other chemokine receptors on MDSC in RCC patients is of interest particularly CCR2 since it is expressed on M-MDSC (100). Indeed, using a mouse tumor model, CCR2+ MDSC were shown to limit the infiltration of activated CD8+ T cells into the tumor and therefore targeting CCR2+ M-MDSC could enhance outcomes in immunotherapy. This strategy is supported by the finding that adoptively transferred CCR2-/- MDSC displayed reduced migration into tumor or spleen and resulted in less MDSC-enhanced tumor growth compared to CCR2+/+ MDSC (101).

C.2 Macrophages

The recruitment of TAM to the tumor is likely mediated by several chemokines including CCL2 which is the ligand for CCR2, a chemokine receptor that is expressed on macrophages. RCC tissue is known to produce CCL2 above the level produced by normal kidney tissue, although isolated TAM from RCC patients also produced CCL2 possibly as a feedback loop to attract more TAM (64). In patients with urothelial and renal carcinoma, a substantial population of peripheral blood MDSC (M- and G-) and tissue derived macrophages express the chemokine receptor CCR8. Isolated CD11+CCR8+ cells produced substantially more IL-6, VEGF, CCL3, and CCL4, than their CCR8-negative counterpart, although for other inspected cytokines/chemokines production was the same for CCR8+ and CCR8- cells (TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-8) (102). However, within tumor the CCR8+ subset of TAM was preferentially STAT3-activated and capable of inducing Foxp3 expression in T lymphocytes. These cells also produced high levels of the CCR8 ligand CCL1. Thus, the CCL1/ CCR8 axis and the CCR2/CCL2 axis appear to represent important players in promoting trafficking of immunosuppressive TAMs to RCC tissue.

C.3 T-regulatory cells

Several chemokine receptor-ligand pairs promote the accumulation of Tregs into human tumors. Tumor cells and TAM produce the chemokine CCL22, which promotes the trafficking of Tregs into tumor via its binding to the chemokine receptor CCR4 expressed on Tregs (103,104) The recruitment of Tregs into tumor via the CCL22-CCR4 axis is associated with poor clinical outcome in breast cancer patients (105). In other tumors the production of CCL5 is important to the trafficking of CCR5+ Tregs (106). In RCC patients Foxp3+ Tregs were found to be enriched within TILs relative to corresponding PBMC PBLs and expressed high levels of CCR5, CXCR3, CXCR6 and CCR6. Even though the ligands for each of these receptors have been detected in tumor tissue, their relative importance for Tregs trafficking into RCC remains speculative. However, CCR6 is likely to play an important role since CCR6 is expressed on Tregs that migrate to CCL20 during in vitro studies (107,108).

C.4 T lymphocytes (effectors and helpers)

The chemokines involved in the recruitment of T cells into tumor include CCL3, CCL5, CCL20 and CXCL10 (96) and are thought to play a role in regulating anti-tumor immunity. In RCC the chemokines promoting T cell migration into tumors appear to be the CXCR3 ligands CXCL9 and CXCL10. High levels of these chemokines were associated with a significant CD8+ T cell infiltrate, correlating with reduced tumor growth and less recurrence in patients with localized RCC (109). Analysis of Th1 and Th2 responses also revealed that CXCR2 and CCR5 along with their corresponding ligands were important for the infiltration of both T cell subsets into RCC tissue. Furthermore, tumors expressing high levels of CXCL9 appear to serve as an independent favorable prognostic factor in RCC patients (110).

It is also clear that the tumor microenvironment can modify chemokines to be less effective at promoting the trafficking of T cells to the tumor. In certain human (colon) and mouse (EG7) tumors the chemokine CCL2, which is chemo-attractive for myeloid cells and T cells, was shown to be nitrated by reactive nitrogen species expressed in the tumor microenvironment (111). The nitration of CCL2 in the tumor hindered T cell infiltration, causing an accumulation of tumor-specific T cells in the stromal rather than penetrating the tumor tissue. Most interestingly, a novel small molecule was developed that blocked nitration of CCL2 and improved T cell infiltration, thus providing a possible approach to reverse this form of immune suppression (111).

D. Cellular dysfunction as a consequence of the tumor microenvironment

D.1 Antigen Presentation

A critical event in the development of an antitumor immunity is T cell recognition of Ag presented by DC. However, in many types of cancer including RCC, the capacity of DC to display Ag is altered, thereby hindering the development of an effective T cell response against tumor. Understanding how the tumor environment impairs DC Ag presentation is thus important for the development of strategies to improve DC function.

D.1.a Dysfunction of DC in the tumor

Several studies have shown that impaired myelopoiesis in the tumor bearing host is a central mechanism to explain DC dysfunction in tumors (11). Within the tumor environment, under the influence of multiple growth factors and cytokines, there is no semblance of normal myeloid differentiation, resulting in low production of mature DC along with enhanced accumulation of immature DC and immature non-DC myeloid cells with suppressive activity (11). Additionally, hypoxia induces HIF1α in DC, resulting in up-regulation of the adenosine receptor (A2B) (112,113). DC expressing A2B receptors promote a type-2 response rather than the type-1 response which is preferable for anti-tumor T cell immunity. Excess adenosine in tumors also induces expression of pro-angiogenic proteins in DC (IL-6, VEGF, IL-8) and boosts production of mediators of suppression (IDO (indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase), COX2, and IL-10) (114). It is also known that intratumoral DC accumulate lipids via the up-regulation of scavenger receptors which diminish the capacity of DC to process antigen for presentation to T cells (115). Others have shown that the tumor microenvironment can induce DC to directly suppress T cell function by producing either arginase or IDO (116,117).

Dysfunctional DC subsets have been characterized in RCC patients (118). The use of specific antibodies that define distinct subsets of DC (BDCA-2 or BDCA-4 for pDC and BDCA-1 for mDC1 and BDCA-3 for mDC2) followed by FACS analysis revealed that mRCC patients had reduced levels of myeloid DC (mDC1, mDC2 ) and plasmacytoid pDC in the peripheral blood. Although there was abundant migration of DC subsets to the tumor they exhibited an immature phenotype (DC-LAMP) and failed to differentiate into mature DC. However when cultured in vitro under the proper conditions RCC derived mDC1 stimulated a strong anti-tumor T cell response to DC pulsed with tumor lysates, suggesting that DC function can be rescued from the tumor microenvironment (118).

D. 2 Effector T cell response in RCC

Analyses of T cell function in patients with localized RCC suggest that the activity of both Th1 (IFN-γ) and Th2 (IL-4) T cell responses are up-regulated in the tumor. Interestingly, RCC expressing high levels of Th1 chemokines and IFN-γ expression did not recur after curative surgery (110,119,120). However, the simultaneous increase in Th2 response in RCC may dampen the development of a potent Th1-type response that would be more favorable for the development of sustained antitumor immunity. Indeed, studies in patients with metastatic RCC revealed a skewing toward a Th2 response when measuring peripheral blood CD8+ and CD4+ T-cell responses against RCC-associated antigens EphA2 and MAGE-6. In marked contrast, immune reactivity to EphA2-derived epitopes was greatly enhanced in CD8+ T cells that had been isolated from patients who were rendered disease-free by surgery. Additionally the majority of patients with active disease were also highly-skewed toward Th2-type responses against MAGE-6-derived epitopes, irrespective of their stage (stage I versus IV) of disease, while normal donors and cancer patients with no current evidence of disease exhibited either mixed Th1/Th2 or strongly Th1-polarized responses to MAGE-6 peptides. These findings suggest that immunotherapeutic approaches will likely have to overcome or at the very least coexist with systemic Th2-dominated, tumor-reactive T cell responses (121-123).

A recent study furthermore showed that CD8+ T cells infiltrating RCC are defective in CD3 stimulation, resulting from impaired activation of downstream targets such as ERK, AKT and JNK, with high expression of diacylglycerol kinase-α (DGK-α). Inhibition of DGK-α expression improved phosphorylation of ERK and AKT, stimulating CTL to degranulate and produce IFN-γ (124).

It remains speculative whether the defective signaling detected in RCC TIL is related to the overexpression of CD70 on RCC and stromal cells, thereby resulting in T cells that display proliferative exhaustion (125). Whereas several studies suggest that CD70 promotes T cell activation, others have shown that CD70-associated RCC induced T cell apoptosis (126). When RCC TIL were compared to those from melanoma patients, TIL from RCC contained lower number of CD27+ T cells as well as fewer naïve and central memory T cells, but more memory effector cells (125). It is possible that the historical difficulty in detecting and expanding tumor- reactive T cells from RCC patients may reflect that a significant proportion of the T cells are in an exhausted state induced by CD70 expression in the RCC microenvironment.

If CD70 promotes suppression then targeting this molecule may be therapeutically relevant. Indeed, anti-CD70 Ab-drug conjugates (ADC) consisting of auristatin phenylalanine phenylenediamine (AFP) or monomethyl auristatin phenylalanine (MMAF), two novel derivatives of the anti-tubulin agent auristatin, can mediate potent Ag-dependent cytotoxicity against CD70-expressing RCC cells. Hence, ADCs targeted to CD70 can selectively recognize RCC, internalize, and reach the appropriate subcellular compartment(s) for drug release and tumor cell killing (127).

E. Conclusions

Recent evidence in vaccine trials underscores that RCC is susceptible to Ag-directed immunotherapy, and that judicious use of cytokines and chemotherapy can potentiate therapeutic responses in RCC as has already proved possible for melanoma. Depletion of inhibitory host cells without impairing effector T cell function can be achieved either with chemotherapy or with the promiscuous rTKI sunitinib. While sunitinib's capacity to deplete MDSC is particularly striking, it appears to be limited to MDSC with chronic STAT3 activation (pSTAT3+), hence ineffective against MDSC with other STAT activation profiles which are especially prone to arise within the tumor bed. Because MDSC typically induce Treg rather than vice versa, gaining control over MDSC, both pSTAT3+ and pSTAT3- MDSC, is an important initial step in any immunotherapy strategy directed at RCC. The most utilitarian strategy to gain control over MDSC may be to exploit the natural differentiation pathway which permits conversion of MDSC into tumoricidal macrophages (TM1) via such stimuli as TLR agonists, IFN-γ and CD40 ligation. This strategy is also likely applicable to other types of solid tumors.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by RO1 CA129815 (P.C.), R01 CA150959 (P.C., J.F.), and RO1 CA 168488 (J.F.)

Footnotes

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Grosh WW. Renal cell carcinoma: treatment with interferon. Compr Ther. 1987;13(6):34–39. Epub 1987/06/01. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gupta K, Miller JD, Li JZ, Russell MW, Charbonneau C. Epidemiologic and socioeconomic burden of metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC): a literature review. Cancer Treat Rev. 2008;34(3):193–205. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2007.12.001. Epub 2008/03/04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosenberg SA, Lotze MT, Muul LM, et al. A progress report on the treatment of 157 patients with advanced cancer using lymphokine-activated killer cells and interleukin-2 or high-dose interleukin-2 alone. N Engl J Med. 1987;316(15):889–897. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198704093161501. Epub 1987/04/09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Escudier B, Goupil MG, Massard C, Fizazi K. Sequential therapy in renal cell carcinoma. Cancer. 2009;115(10 Suppl):2321–2326. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24241. Epub 2009/04/30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaelin WG., Jr The von Hippel-Lindau tumour suppressor protein: O2 sensing and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8(11):865–873. doi: 10.1038/nrc2502. Epub 2008/10/17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jonasch E, Futreal PA, Davis IJ, et al. State of the science: an update on renal cell carcinoma. Mol Cancer Res. 10(7):859–880. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-12-0117. Epub 2012/05/29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vira MA, Novakovic KR, Pinto PA, Linehan WM. Genetic basis of kidney cancer: a model for developing molecular-targeted therapies. BJU Int. 2007;99(5 Pt B):1223–1229. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.06814.x. Epub 2007/04/20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kerkar SP, Restifo NP. Cellular constituents of immune escape within the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Res. 72(13):3125–3130. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-4094. Epub 2012/06/23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cohen PA, Ko JS, Storkus WJ, et al. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells adhere to physiologic STAT3- vs STAT5-dependent hematopoietic programming, establishing diverse tumor-mediated mechanisms of immunologic escape. Immunol Invest. 2012;41(6-7):680–710. doi: 10.3109/08820139.2012.703745. Epub 2012/09/29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ko JS, Rayman P, Ireland J, et al. Direct and differential suppression of myeloid-derived suppressor cell subsets by sunitinib is compartmentally constrained. Cancer Res. 2010;70(9):3526–3536. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3278. Epub 2010/04/22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gabrilovich D. Mechanisms and functional significance of tumour-induced dendritic-cell defects. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4(12):941–952. doi: 10.1038/nri1498. Epub 2004/12/02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peranzoni E, Zilio S, Marigo I, et al. Myeloid-derived suppressor cell heterogeneity and subset definition. Curr Opin Immunol. 22(2):238–244. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2010.01.021. Epub 2010/02/23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rodriguez PC, Ernstoff MS, Hernandez C, et al. Arginase I-producing myeloid-derived suppressor cells in renal cell carcinoma are a subpopulation of activated granulocytes. Cancer Res. 2009;69(4):1553–1560. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1921. Epub 2009/02/10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Srivastava MK, Sinha P, Clements VK, Rodriguez P, Ostrand-Rosenberg S. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells inhibit T-cell activation by depleting cystine and cysteine. Cancer Res. 70(1):68–77. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2587. Epub 2009/12/24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Corzo CA, Cotter MJ, Cheng P, et al. Mechanism regulating reactive oxygen species in tumor-induced myeloid-derived suppressor cells. J Immunol. 2009;182(9):5693–5701. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900092. Epub. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kusmartsev S, Su Z, Heiser A, et al. Reversal of myeloid cell-mediated immunosuppression in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(24):8270–8278. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0165. Epub 2008/12/18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nagaraj S, Gupta K, Pisarev V, et al. Altered recognition of antigen is a mechanism of CD8+ T cell tolerance in cancer. Nat Med. 2007;13(7):828–835. doi: 10.1038/nm1609. Epub 2007/07/03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang B, Pan PY, Li Q, et al. Gr-1+CD115+ immature myeloid suppressor cells mediate the development of tumor-induced T regulatory cells and T-cell anergy in tumor-bearing host. Cancer Res. 2006;66(2):1123–1131. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1299. Epub. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pan PY, Ma G, Weber KJ, et al. Immune stimulatory receptor CD40 is required for T-cell suppression and T regulatory cell activation mediated by myeloid-derived suppressor cells in cancer. Cancer Res. 70(1):99–108. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1882. Epub 2009/12/10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hanson EM, Clements VK, Sinha P, Ilkovitch D, Ostrand-Rosenberg S. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells down-regulate L-selectin expression on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. J Immunol. 2009;183(2):937–944. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0804253. Epub 2009/06/26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang L, DeBusk LM, Fukuda K, et al. Expansion of myeloid immune suppressor Gr+CD11b+ cells in tumor-bearing host directly promotes tumor angiogenesis. Cancer Cell. 2004;6(4):409–421. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.08.031. Epub 2004/10/19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kujawski M, Kortylewski M, Lee H, Herrmann A, Kay H, Yu H. Stat3 mediates myeloid cell-dependent tumor angiogenesis in mice. J Clin Invest. 2008;118(10):3367–3377. doi: 10.1172/JCI35213. Epub 2008/09/09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walter S, Weinschenk T, Stenzl A, et al. Multipeptide immune response to cancer vaccine IMA901 after single-dose cyclophosphamide associates with longer patient survival. Nat Med. doi: 10.1038/nm.2883. Epub 2012/07/31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zea AH, Rodriguez PC, Atkins MB, et al. Arginase-producing myeloid suppressor cells in renal cell carcinoma patients: a mechanism of tumor evasion. Cancer Res. 2005;65(8):3044–3048. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4505. Epub. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ko JS, Rayman P, Ireland J, et al. Direct and differential suppression of myeloid-derived suppressor cell subsets by sunitinib is compartmentally constrained. Cancer Res. 70(9):3526–3536. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3278. Epub 2010/04/22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ko JS, Zea AH, Rini BI, et al. Sunitinib mediates reversal of myeloid-derived suppressor cell accumulation in renal cell carcinoma patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(6):2148–2157. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1332. Epub 2009/03/12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Youn JI, Collazo M, Shalova IN, Biswas SK, Gabrilovich DI. Characterization of the nature of granulocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells in tumor-bearing mice. J Leukoc Biol. 91(1):167–181. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0311177. Epub 2011/09/29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sippel TR, White J, Nag K, et al. Neutrophil degranulation and immunosuppression in patients with GBM: restoration of cellular immune function by targeting arginase I. Clin Cancer Res. 17(22):6992–7002. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1107. Epub 2011/09/29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fridlender ZG, Sun J, Mishalian I, et al. Transcriptomic analysis comparing tumor-associated neutrophils with granulocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells and normal neutrophils. PLoS One. 7(2):e31524. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031524. Epub 2012/02/22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schmielau J, Finn OJ. Activated granulocytes and granulocyte-derived hydrogen peroxide are the underlying mechanism of suppression of t-cell function in advanced cancer patients. Cancer Res. 2001;61(12):4756–4760. Epub. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brandau S, Trellakis S, Bruderek K, et al. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the peripheral blood of cancer patients contain a subset of immature neutrophils with impaired migratory properties. J Leukoc Biol. 89(2):311–317. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0310162. Epub 2010/11/26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marigo I, Bosio E, Solito S, et al. Tumor-induced tolerance and immune suppression depend on the C/EBPbeta transcription factor. Immunity. 32(6):790–802. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.05.010. Epub 2010/07/08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Youn JI, Kumar V, Collazo M, et al. Epigenetic silencing of retinoblastoma gene regulates pathologic differentiation of myeloid cells in cancer. Nat Immunol. 14(3):211–220. doi: 10.1038/ni.2526. Epub 2013/01/29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Choueiri TK, Garcia JA, Elson P, et al. Clinical factors associated with outcome in patients with metastatic clear-cell renal cell carcinoma treated with vascular endothelial growth factor-targeted therapy. Cancer. 2007;110(3):543–550. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22827. Epub 2007/06/20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Donskov F, von der Maase H. Impact of immune parameters on long-term survival in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(13):1997–2005. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.9594. Epub 2006/05/02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Donskov F. Immunomonitoring and prognostic relevance of neutrophils in clinical trials. Semin Cancer Biol. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2013.02.001. Epub 2013/02/14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lopez-Lago MA, Posner S, Thodima VJ, Molina AM, Motzer RJ, Chaganti RS. Neutrophil chemokines secreted by tumor cells mount a lung antimetastatic response during renal cell carcinoma progression. Oncogene. 32(14):1752–1760. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.201. Epub 2012/06/06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Negrier S, Escudier B, Gomez F, et al. Prognostic factors of survival and rapid progression in 782 patients with metastatic renal carcinomas treated by cytokines: a report from the Groupe Francais d'Immunotherapie. Ann Oncol. 2002;13(9):1460–1468. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdf257. Epub 2002/08/28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jensen HK, Donskov F, Marcussen N, Nordsmark M, Lundbeck F, von der Maase H. Presence of intratumoral neutrophils is an independent prognostic factor in localized renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(28):4709–4717. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.9498. Epub 2009/09/02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Najjar YG, Finke JH. Clinical perspectives on targeting of myeloid derived suppressor cells in the treatment of cancer. Front Oncol. 3:49. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2013.00049. Epub 2013/03/20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mirza N, Fishman M, Fricke I, et al. All-trans-retinoic acid improves differentiation of myeloid cells and immune response in cancer patients. Cancer Res. 2006;66(18):9299–9307. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1690. Epub 2006/09/20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nefedova Y, Fishman M, Sherman S, Wang X, Beg AA, Gabrilovich DI. Mechanism of all-trans retinoic acid effect on tumor-associated myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67(22):11021–11028. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2593. Epub 2007/11/17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Beatty GL, Chiorean EG, Fishman MP, et al. CD40 agonists alter tumor stroma and show efficacy against pancreatic carcinoma in mice and humans. Science. 2011;331(6024):1612–1616. doi: 10.1126/science.1198443. Epub 2011/03/26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shirota Y, Shirota H, Klinman DM. Intratumoral injection of CpG oligonucleotides induces the differentiation and reduces the immunosuppressive activity of myeloid-derived suppressor cells. J Immunol. 2012;188(4):1592–1599. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101304. Epub 2012/01/11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liscovsky MV, Ranocchia RP, Alignani DO, et al. CpG-ODN+IFN-gamma confer pro- and anti-inflammatory properties to peritoneal macrophages in aged mice. Experimental gerontology. 46(6):462–467. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2011.01.006. Epub. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zembala M, Siedlar M, Marcinkiewicz J, Pryjma J. Human monocytes are stimulated for nitric oxide release in vitro by some tumor cells but not by cytokines and lipopolysaccharide. Eur J Immunol. 24(2):435–439. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830240225. Epub 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nagaraj S, Youn JI, Weber H, et al. Anti-inflammatory triterpenoid blocks immune suppressive function of MDSCs and improves immune response in cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 16(6):1812–1823. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-3272. Epub 2010/03/11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.van Cruijsen H, van der Veldt AA, Vroling L, et al. Sunitinib-induced myeloid lineage redistribution in renal cell cancer patients: CD1c+ dendritic cell frequency predicts progression-free survival. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(18):5884–5892. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0656. Epub 2008/09/17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Finke JH, Rini B, Ireland J, et al. Sunitinib reverses type-1 immune suppression and decreases T-regulatory cells in renal cell carcinoma patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(20):6674–6682. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-5212. Epub 2008/10/18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bose A, Taylor JL, Alber S, et al. Sunitinib facilitates the activation and recruitment of therapeutic anti-tumor immunity in concert with specific vaccination. Int J Cancer. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25863. Epub. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Farsaci B, Higgins JP, Hodge JW. Consequence of dose scheduling of sunitinib on host immune response elements and vaccine combination therapy. Int J Cancer. 130(8):1948–1959. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26219. Epub 2011/06/03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kujawski M, Zhang C, Herrmann A, et al. Targeting STAT3 in adoptively transferred T cells promotes their in vivo expansion and antitumor effects. Cancer Res. 70(23):9599–9610. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1293. Epub 2010/12/02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ozao-Choy J, Ma G, Kao J, et al. The novel role of tyrosine kinase inhibitor in the reversal of immune suppression and modulation of tumor microenvironment for immune-based cancer therapies. Cancer Res. 2009;69(6):2514–2522. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4709. Epub 2009/03/12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ferrara N. Role of myeloid cells in vascular endothelial growth factor-independent tumor angiogenesis. Curr Opin Hematol. 17(3):219–224. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e3283386660. Epub 2010/03/24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Phan VT, Wu X, Cheng JH, et al. Oncogenic RAS pathway activation promotes resistance to anti-VEGF therapy through G-CSF-induced neutrophil recruitment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 110(15):6079–6084. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1303302110. Epub 2013/03/27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cohen PA, Koski GK, Czerniecki BJ, et al. STAT3- and STAT5-dependent pathways competitively regulate the pan-differentiation of CD34pos cells into tumor-competent dendritic cells. Blood. 2008;112(5):1832–43. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-12-130138. Epub 2008 Jun 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Xin H, Zhang C, Herrmann A, Du Y, Figlin R, Yu H. Sunitinib inhibition of Stat3 induces renal cell carcinoma tumor cell apoptosis and reduces immunosuppressive cells. Cancer Res. 2009;69(6):2506–2513. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4323. Epub 2009/02/27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yang F, Jove V, Xin H, Hedvat M, Van Meter TE, Yu H. Sunitinib induces apoptosis and growth arrest of medulloblastoma tumor cells by inhibiting STAT3 and AKT signaling pathways. Mol Cancer Res. 2010;8(1):35–45. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-09-0220. Epub 2010/01/08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zorro Manrique S, Spencer C, Dominguez A, et al. Global targeting of MDSC escape mechanisms cures advanced 4T1 breast tumors (P2062) The Journal of Immunology. 190(Meeting Abstracts 1):132.121. Epub. [Google Scholar]

- 60.De Palma M, Lewis CE. Macrophage regulation of tumor responses to anticancer therapies. Cancer Cell. 23(3):277–286. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.02.013. Epub 2013/03/23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Colombo MP, Mantovani A. Targeting myelomonocytic cells to revert inflammation-dependent cancer promotion. Cancer Res. 2005;65(20):9113–9116. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2714. Epub 2005/10/19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Movahedi K, Laoui D, Gysemans C, et al. Different tumor microenvironments contain functionally distinct subsets of macrophages derived from Ly6C(high) monocytes. Cancer research. 2010;70(14):5728–5739. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-4672. Epub 2010/06/24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Biswas SK, Mantovani A. Macrophage plasticity and interaction with lymphocyte subsets: cancer as a paradigm. Nat Immunol. 11(10):889–896. doi: 10.1038/ni.1937. Epub 2010/09/22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Daurkin I, Eruslanov E, Stoffs T, et al. Tumor-associated macrophages mediate immunosuppression in the renal cancer microenvironment by activating the 15-lipoxygenase-2 pathway. Cancer Res. 71(20):6400–6409. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1261. Epub 2011/09/09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Komohara Y, Hasita H, Ohnishi K, et al. Macrophage infiltration and its prognostic relevance in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 102(7):1424–1431. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2011.01945.x. Epub 2011/04/02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Menke J, Kriegsmann J, Schimanski CC, Schwartz MM, Schwarting A, Kelley VR. Autocrine CSF-1 and CSF-1 receptor coexpression promotes renal cell carcinoma growth. Cancer Res. 72(1):187–200. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1232. Epub 2011/11/05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hori S, Nomura T, Sakaguchi S. Control of regulatory T cell development by the transcription factor Foxp3. Science. 2003;299(5609):1057–1061. doi: 10.1126/science.1079490. Epub 2003/01/11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Barbi J, Pardoll D, Pan F. Metabolic control of the Treg/Th17 axis. Immunol Rev. 252(1):52–77. doi: 10.1111/imr.12029. Epub 2013/02/15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Liu W, Putnam AL, Xu-Yu Z, et al. CD127 expression inversely correlates with FoxP3 and suppressive function of human CD4+ T reg cells. J Exp Med. 2006;203(7):1701–1711. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060772. Epub 2006/07/05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Menetrier-Caux C, Curiel T, Faget J, Manuel M, Caux C, Zou W. Targeting regulatory T cells. Target Oncol. 7(1):15–28. doi: 10.1007/s11523-012-0208-y. Epub 2012/02/14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jago CB, Yates J, Camara NO, Lechler RI, Lombardi G. Differential expression of CTLA-4 among T cell subsets. Clin Exp Immunol. 2004;136(3):463–471. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2004.02478.x. Epub 2004/05/19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.McHugh RS, Whitters MJ, Piccirillo CA, et al. CD4(+)CD25(+) immunoregulatory T cells: gene expression analysis reveals a functional role for the glucocorticoid-induced TNF receptor. Immunity. 2002;16(2):311–323. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00280-7. Epub 2002/03/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Misra N, Bayry J, Lacroix-Desmazes S, Kazatchkine MD, Kaveri SV. Cutting edge: human CD4+CD25+ T cells restrain the maturation and antigen-presenting function of dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2004;172(8):4676–4680. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.8.4676. Epub 2004/04/07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gondek DC, Lu LF, Quezada SA, Sakaguchi S, Noelle RJ. Cutting edge: contact-mediated suppression by CD4+CD25+ regulatory cells involves a granzyme B-dependent, perforin-independent mechanism. J Immunol. 2005;174(4):1783–1786. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.4.1783. Epub 2005/02/09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Grossman WJ, Verbsky JW, Barchet W, Colonna M, Atkinson JP, Ley TJ. Human T regulatory cells can use the perforin pathway to cause autologous target cell death. Immunity. 2004;21(4):589–601. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.09.002. Epub 2004/10/16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Borsellino G, Kleinewietfeld M, Di Mitri D, et al. Expression of ectonucleotidase CD39 by Foxp3+ Treg cells: hydrolysis of extracellular ATP and immune suppression. Blood. 2007;110(4):1225–1232. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-12-064527. Epub 2007/04/24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Deaglio S, Dwyer KM, Gao W, et al. Adenosine generation catalyzed by CD39 and CD73 expressed on regulatory T cells mediates immune suppression. J Exp Med. 2007;204(6):1257–1265. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062512. Epub 2007/05/16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cesana GC, DeRaffele G, Cohen S, et al. Characterization of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells in patients treated with high-dose interleukin-2 for metastatic melanoma or renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(7):1169–1177. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.6830. Epub 2006/03/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Griffiths RW, Elkord E, Gilham DE, et al. Frequency of regulatory T cells in renal cell carcinoma patients and investigation of correlation with survival. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2007;56(11):1743–1753. doi: 10.1007/s00262-007-0318-z. Epub 2007/05/10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ning H, Shao QQ, Ding KJ, et al. Tumor-infiltrating regulatory T cells are positively correlated with angiogenic status in renal cell carcinoma. Chin Med J (Engl) 125(12):2120–2125. Epub 2012/08/14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Polimeno M, Napolitano M, Costantini S, et al. Regulatory T cells, interleukin (IL)-6, IL-8, Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), CXCL10, CXCL11, epidermal growth factor (EGF) and hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) as surrogate markers of host immunity in patients with renal cell carcinoma. BJU Int. doi: 10.1111/bju.12068. Epub 2013/03/19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Schwarzer A, Wolf B, Fisher JL, et al. Regulatory T-cells and associated pathways in metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC) patients undergoing DC-vaccination and cytokine-therapy. PLoS One. 7(10):e46600. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046600. Epub 2012/11/03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sell K, Barth PJ, Moll R, et al. Localization of FOXP3-positive cells in renal cell carcinoma. Tumour Biol. 33(2):507–513. doi: 10.1007/s13277-011-0283-1. Epub 2011/12/07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Siddiqui SA, Frigola X, Bonne-Annee S, et al. Tumor-infiltrating Foxp3-CD4+CD25+ T cells predict poor survival in renal cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(7):2075–2081. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2139. Epub 2007/04/04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Li JF, Chu YW, Wang GM, et al. The prognostic value of peritumoral regulatory T cells and its correlation with intratumoral cyclooxygenase-2 expression in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. BJU Int. 2009;103(3):399–405. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.08151.x. Epub 2008/11/22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Roncarolo MG, Gregori S, Battaglia M, Bacchetta R, Fleischhauer K, Levings MK. Interleukin-10-secreting type 1 regulatory T cells in rodents and humans. Immunol Rev. 2006;212:28–50. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00420.x. Epub 2006/08/15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Weiner HL. Induction and mechanism of action of transforming growth factor-beta-secreting Th3 regulatory cells. Immunol Rev. 2001;182:207–214. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2001.1820117.x. Epub 2001/11/28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wolf B, Schwarzer A, Cote AL, et al. Gene expression profile of peripheral blood lymphocytes from renal cell carcinoma patients treated with IL-2, interferon-alpha and dendritic cell vaccine. PLoS One. 7(12):e50221. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050221. Epub 2012/12/12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Shimizu J, Yamazaki S, Sakaguchi S. Induction of tumor immunity by removing CD25+CD4+ T cells: a common basis between tumor immunity and autoimmunity. J Immunol. 1999;163(10):5211–5218. Epub 1999/11/24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Rech AJ, Vonderheide RH. Clinical use of anti-CD25 antibody daclizumab to enhance immune responses to tumor antigen vaccination by targeting regulatory T cells. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1174:99–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04939.x. Epub 2009/09/23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Dannull J, Su Z, Rizzieri D, et al. Enhancement of vaccine-mediated antitumor immunity in cancer patients after depletion of regulatory T cells. J Clin Invest. 2005;115(12):3623–3633. doi: 10.1172/JCI25947. Epub 2005/11/26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Adotevi O, Pere H, Ravel P, et al. A decrease of regulatory T cells correlates with overall survival after sunitinib-based antiangiogenic therapy in metastatic renal cancer patients. J Immunother. 33(9):991–998. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3181f4c208. Epub 2010/10/16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Desar IM, Jacobs JH, Hulsbergen-vandeKaa CA, et al. Sorafenib reduces the percentage of tumour infiltrating regulatory T cells in renal cell carcinoma patients. Int J Cancer. 129(2):507–512. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25674. Epub 2010/09/15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kavanagh B, O'Brien S, Lee D, et al. CTLA4 blockade expands FoxP3+ regulatory and activated effector CD4+ T cells in a dose-dependent fashion. Blood. 2008;112(4):1175–1183. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-11-125435. Epub 2008/06/05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Maker AV, Attia P, Rosenberg SA. Analysis of the cellular mechanism of antitumor responses and autoimmunity in patients treated with CTLA-4 blockade. J Immunol. 2005;175(11):7746–7754. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.11.7746. Epub 2005/11/23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Franciszkiewicz K, Boissonnas A, Boutet M, Combadiere C, Mami-Chouaib F. Role of chemokines and chemokine receptors in shaping the effector phase of the antitumor immune response. Cancer Res. 72(24):6325–6332. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2027. Epub 2012/12/12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Yang L, Huang J, Ren X, et al. Abrogation of TGF beta signaling in mammary carcinomas recruits Gr-1+CD11b+ myeloid cells that promote metastasis. Cancer Cell. 2008;13(1):23–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.12.004. Epub 2008/01/03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.D'Alterio C, Consales C, Polimeno M, et al. Concomitant CXCR4 and CXCR7 expression predicts poor prognosis in renal cancer. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 10(7):772–781. doi: 10.2174/156800910793605839. Epub 2010/06/29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Zagzag D, Krishnamachary B, Yee H, et al. Stromal cell-derived factor-1alpha and CXCR4 expression in hemangioblastoma and clear cell-renal cell carcinoma: von Hippel-Lindau loss-of-function induces expression of a ligand and its receptor. Cancer Res. 2005;65(14):6178–6188. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4406. Epub 2005/07/19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Lesokhin AM, Hohl TM, Kitano S, et al. Monocytic CCR2(+) myeloid-derived suppressor cells promote immune escape by limiting activated CD8 T-cell infiltration into the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Res. 72(4):876–886. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1792. Epub 2011/12/17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Huang B, Lei Z, Zhao J, et al. CCL2/CCR2 pathway mediates recruitment of myeloid suppressor cells to cancers. Cancer Lett. 2007;252(1):86–92. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2006.12.012. Epub 2007/01/30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Eruslanov E, Stoffs T, Kim WJ, et al. Expansion of CCR8+ Inflammatory Myeloid Cells in Cancer Patients with Urothelial and Renal Carcinomas. Clin Cancer Res. 19(7):1670–1680. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-2091. Epub 2013/02/01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Jordan JT, Sun W, Hussain SF, DeAngulo G, Prabhu SS, Heimberger AB. Preferential migration of regulatory T cells mediated by glioma-secreted chemokines can be blocked with chemotherapy. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2008;57(1):123–131. doi: 10.1007/s00262-007-0336-x. Epub 2007/05/25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Curiel TJ, Coukos G, Zou L, et al. Specific recruitment of regulatory T cells in ovarian carcinoma fosters immune privilege and predicts reduced survival. Nature medicine. 2004;10(9):942–949. doi: 10.1038/nm1093. Epub 2004/08/24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Friedman RS, Jacobelli J, Krummel MF. Surface-bound chemokines capture and prime T cells for synapse formation. Nat Immunol. 2006;7(10):1101–1108. doi: 10.1038/ni1384. Epub 2006/09/12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Tan MC, Goedegebuure PS, Belt BA, et al. Disruption of CCR5-dependent homing of regulatory T cells inhibits tumor growth in a murine model of pancreatic cancer. J Immunol. 2009;182(3):1746–1755. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.3.1746. Epub 2009/01/22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]