Abstract

Background

Social networking technologies are an emerging tool for HIV prevention.

Objective

To determine whether social networking communities can increase HIV testing among African American and Latino men who have sex with men (MSM).

Design

Randomized; controlled trial with concealed allocation (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT01701206).

Setting

Online.

Patients

112 MSM based in Los Angeles, more than 85% of whom were African American or Latino.

Intervention

Sixteen peer leaders were randomly assigned to deliver information about HIV or general health to participants via Facebook groups over 12 weeks. After participants accepted a request to join the group, participation was voluntary. Group participation and engagement was monitored. Participants could request a free home-based HIV testing kit and completed questionnaires at baseline and 12-week follow-up.

Measurements

Participant acceptance of and engagement in the intervention and social network participation, rates of home-based HIV testing, and sexual risk behaviors.

Results

Almost 95% of intervention participants and 73% of control participants voluntarily communicated using the social platform. Twenty-five of the 57 intervention participants (44%) requested home-based HIV testing kits compared with 11 of 55 control participants (20%) (difference, 24 percentage points [95% CI, 8 to 41 percentage points]). Nine of the 25 intervention participants (36%) who requested the test took it and mailed it back compared with 2 of the 11 control participants (18%) who requested the test. Retention at study follow-up was more 93%.

Limitations

Only 2 Facebook communities were included for each group.

Conclusions

Social networking communities are acceptable and effective tools to increase home-based HIV testing among at-risk populations.

Primary funding source

National Institute of Mental Health

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier

Keywords: HIV prevention, social networking, at-risk populations, MSM

INTRODUCTION

African Americans and Latinos in Los Angeles, California, as in the rest of the United States, have high rates of incident cases of HIV and new diagnoses (1, 2). Since 1981, most of these cases have been attributable to men who have sex with men (MSM), currently accounting for up to 82% of all infections (2). Researchers have proposed using novel strategies to increase HIV prevention and testing efforts among African-American and Latino MSM.

The community peer-leader model is designed to increase HIV prevention and testing behaviors by changing social norms (3, 4). These interventions, which enlist peer health educators to disseminate HIV-related information to their communities, have increased condom use and decreased unprotected anal intercourse, with sustained behavior change up to 3 years later (5, 6). To address the potentially high cost of these community-based interventions, online methods have been proposed as a way to rapidly and cost-effectively deliver widespread HIV prevention (7–9).

Addressing at-risk populations of Internet users is especially important because those who seek sex on the Internet may be at increased risk for HIV (10–13). Use of online social networking has grown exponentially, especially among communities of African Americans, Latinos, and MSM (14–17). These networks are thus potentially useful platforms for delivering a peer-led intervention on HIV prevention (18, 19). However, this approach has not been systematically tested.

The HOPE (Harnessing Online Peer Education) study tests the feasibility, acceptability, and effectiveness of using social networking sites (specifically Facebook) to increase HIV prevention and testing. This 12-week intervention, designed primarily for African American and Latino MSM, tested whether participants who received peer-delivered information on HIV prevention over Facebook compared with those who received peer-delivered information on general health over Facebook were more likely to request a home-based HIV testing kit, report decreased sexual risk behaviors, and find social networking communities to be acceptable and engaging platforms for HIV prevention. This article presents the results of those primary outcomes.

METHODS

This study was reviewed and approved by the Human Subjects Board of the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). Methods conform to current recommendations on using social networking for HIV prevention (19). Between September 2010 and January 2011, a total of 122 participants were recruited from online venues (n = 104), community venues (n = 6) frequented by African American and Latino MSM (for example, restaurants, clubs, schools, and universities), and direct referrals from participants (n = 12). Six participants completed only the first 15 responses and were excluded from the analysis. Before randomization, we found that 4 participants completed multiple surveys; we included their most recent responses, leaving a total of 112 valid responses.

Community venue staff were contacted and provided potential participants with fliers stating that the HOPE UCLA study was seeking African American or Latino participants, aged 18 years or older who were MSM. Fliers provided a contact e-mail address and Web link for additional information and registration.

Participants were recruited from the Internet and social networking sites through paid, targeted banner ads on social networking sites such as Facebook; recruitment posts on the personals and jobs sections on Craigslist in the greater Los Angeles area; and a Facebook fan page with study information taken from community fliers. Participants were told that they could recommend the Web site to friends who were interested and fit inclusion criteria.

Interested candidates were screened for eligibility on the Web site. Participants met the following criteria: African American or Latino man, age 18 years or older, has a Facebook account, self-reported living in the Los Angeles area, and had sex with a man in the past 12 months. A “Facebook Connect” technology application was created to verify each participant’s unique Facebook user status (19). Because this application reduced the anticipated speed of enrollment of African American and Latino MSM, we first recruited 70% of the sample from these populations and then opened enrollment to a small number of participants who were not African American or Latino to prevent study delays.

Because the intervention was based on social network participation, all participants registered before taking the baseline survey so that they could begin the study concurrently. Once 112 valid participants enrolled, they were randomly assigned to 1 or 2 intervention or control groups and were sent an e-mail with a link to an online baseline survey.

Recruitment and Training of Peer Leaders

On the basis of research showing that 15% of a population would be needed for a peer intervention (3), 18 peer leaders were recruited from community organizations serving African American and Latino MSM. Organization staff gave study fliers to potential peer leaders fitting inclusion criteria: friendly and well-respected African American or Latino MSM aged 18 years or older, having had sex with a man in the past 12 months, having a Facebook account or being willing to create one, and being interested in educating others about health. Potential peer leaders visited the study Web site for an online eligibility screening.

Peer leaders who satisfied enrollment criteria were informed about the study design and were randomly assigned to the HIV (intervention) group or general health (control) group. Peer leaders were informed about study goals but were asked to not disclose this information to participants. All peer leaders attended three 3-hour training sessions at UCLA according to their group (HIV or general health).

Training sessions provided lessons on the epidemiology of HIV or general health subjects and ways of using Facebook to discuss health and stigmatizing topics. Peer leaders were given baseline and final questionnaires to ensure they had gained necessary skills. Additional information about peer leaders and training is available online (20). Two peer leaders (1 in each group) did not finish the training, leaving 16 leaders who were trained and qualified to conduct the intervention. Peer leaders were paid in electronic gift cards for their study participation ($30 for the initial 4 weeks; $40 for the next 4 weeks; $50 for the final 4 weeks).

Intervention

Facebook was used to create closed groups (unable to be accessed or searched for by persons who were not group members) for the 2 control and 2 intervention groups. Participants were randomly and blindly assigned to 1 of 2 intervention or control groups and then randomly assigned to 2 peer leaders within that group. Each group was designed to have 28 participants and 4 peer leaders. Randomization was performed by a random-number generator with participants blinded to assignment and unable to be placed in a group or condition at their own request. No participants or peer leaders were involved in randomization.

During each week of the 12-week study from March through June 2011, peer leaders attempted to communicate with their assigned participants on Facebook, by sending messages, chats, and wall posts. In addition to general conversation, peer leaders in the intervention group were instructed to communicate about HIV prevention and testing, whereas those in the control group communicated the importance of exercising, healthy eating, and maintaining a low-stress lifestyle.

Because best practices for health and social media communication have not been established, peer leaders talked weekly with their trainers on how to increase participant engagement. For example, in the first week, peer leaders were instructed to send friendly messages to elicit a basic response from participants. Peer leaders were advised to tailor messages each week based on the basis of participant responses and engagement. They were not required but were allowed to interact with other participants in their group.

Participants were instructed to use Facebook as they normally would, with no obligation to respond to or engage with peer leaders or other participants or to remain a member of the Facebook group. Participants could control the amount of personal information that they shared with other group members by adjusting their Facebook settings. They were not provided guidance on whether they could interact with each other outside of the study context.

To monitor intervention content and fidelity peer leaders returned “response sheets” each week that indicated whether and which participants had responded to their contact attempts, coded by date, contact method, content topic, and participant engagement. Every 4 weeks, participants in both groups were told that they could request a free, home-based testing kit (Home Access HIV-1 Test System, Home Access Health, Hoffman Estates, Illinois). Each participant was able to receive 1 kit during the 12-week study.

Each kit included a personal identification number associated with the participant. Participant identification and testing kit numbers were documented before HIV kits were sent to participants. Home Access Health provided the personal identification numbers on the testing kits that were returned along with data on rates of participant follow-up to receive test results.

At baseline and follow-up (12 weeks after baseline), participants completed a 92-item survey (21) that focused on demographic characteristics; Internet and social media use (including comfort using the Internet and social media to talk about health and sexual risk behaviors); general health behaviors, such as exercise and nutrition; and sex and sexual health behaviors (including HIV testing and treatment). Demographic characteristics, HIV risk, and general health-related items had been validated in previous studies; Internet and social media items were created specifically for this study.

Primary intervention end points were based on verifiable behavior change from baseline to follow-up: request for a home-based testing kit, returning the kit, and following up for test results. Secondary end points were self-reported reduction in number of sexual partners and observed and self-reported communication using the social networking community.

Statistical Analysis

Sample size was originally set assuming 7 clusters per condition. Twenty-five participants per cluster (185 total per condition) provided 80% power to detect between-group difference in HIV testing of 16 percentage points or more. Fiscal constraints required us to scale back the number of clusters to 2.

Statistical analyses were done using Stata, version 12 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas). Demographic characteristics measured at baseline were compared using chi-square tests for categorical variables and t tests for continuous outcomes. Metrics for online community participation and engagement were summarized for each 4-week period and group. Data on community group participation were available at the condition level but not at the individual cluster level. Requests for HIV testing kits, returned tests and follow-up, social media use and sexual risk behavior were summarized by individual Facebook group, within condition. The 95% CI for the between-group difference in rates of HIV testing requests was calculated using the SE for the linear contrast comparing the average of the rates in the 2 intervention groups with that in the 2 control groups.

Role of the Funding Source

This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health; UCLA Center for HIV Identification, Prevention and Treatment Services; and the UCLA AIDS Institute. The funding sources played no role in study design, analysis, or manuscript preparation.

RESULTS

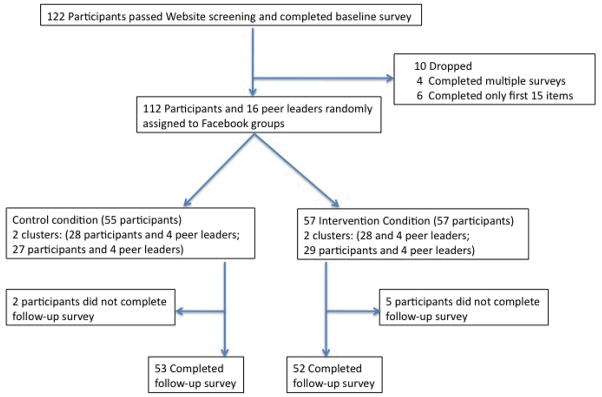

Between September 2010 and June 2011, a total of 112 participants were randomly assigned to an intervention (n=57) or control (n=55) group (Figure).

Figure.

Study flow diagram.

Participant flow chart, Los Angeles, CA, 2011.

Table 1 presents data on baseline socio-demographics characteristics. Participants’ mean age was 31.5 years; 60% of participants were Latino, 28% African American, 11% white, and 2% Asian. Almost 60% reported having a high school diploma, GED, or associate’s degree, and more than 35% reported having a bachelor’s degree or higher. The control group had more single participants than the intervention group (91% vs. 75%), and the intervention group had more persons who completed postsecondary education than the control group (65% vs. 56%)

Table 1.

Baseline Demographic Characteristics Among MSM Recruited Using Online and Offline Methods

| Characteristics: | Control Group (n = 55) | HIV group (n=57) | Total (n=112) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean, SD), y | 31.8 (9.8) | 31.2 (10.6) | 31.5 (10.2) |

| Race, n (%) | |||

| African American | 14 (25.5%) | 17 (29.8%) | 31 (27.7%) |

| Latino | 33 (60.0%) | 34 (59.7%) | 67 (59.8%) |

| White | 7 (12.7%) | 5 (8.8%) | 12 (10.7%) |

| Asian | 1 (1.8%) | 1 (1.8%) | 2 (1.8%) |

| Highest Education, n (%) | |||

| Less than high school | 1 (1.8%) | 3 (5.3%) | 4 (3.6%) |

| High School | 20 (36.4%) | 14 (24.6%) | 34 (30.4%) |

| GED | 3 (5.5%) | 3 (5.3%) | 6 (5.4%) |

| Associates | 11 (20.0%) | 14 (24.6%) | 25 (22.3%) |

| Bachelors | 14 (25.5%) | 16 (28.1%) | 30 (26.8%) |

| Graduate school | 6 (10.9%) | 7 (12.3%) | 13 (11.6%) |

| Monthly Income, n (%) | |||

| $1000 or less | 27 (49.1%) | 31 (54.4%) | 58 (51.8%) |

| $1001 – $2000 | 14 (25.5%) | 9 (15.8%) | 23 (20.5%) |

| $2001 – $3000 | 5 (9.1%) | 11 (19.3%) | 16 (14.3%) |

| > $3000 | 9 (16.4%) | 6 (10.5%) | 15 (13.4%) |

| Birthplace, n (%) | |||

| Northern USA | 9 (16.4%) | 7 (12.3%) | 16 (14.3%) |

| Southern USA | 5 (9.1%) | 7 (12.3%) | 12 (10.7%) |

| Eastern USA | 4 (7.3%) | 3 (5.3%) | 7(6.3%) |

| Western USA | 32 (58.2%) | 38 (66.7%) | 70 (62.5%) |

| Latin America/Caribbean | 4 (7.3%) | 2 (1.8%) | 6 (5.4%) |

| Self-described sexual orientation, n (%) | |||

| Gay | 43 (78.2%) | 42 (73.7%) | 85 (75.9%) |

| Bisexual | 11 (20.0%) | 10 (17.5%) | 21 (18.8%) |

| Heterosexual/questioning/don’t know | 1 (1.8%) | 5 (8.8%) | 6 (5.4%) |

| Current marital status, n (%) | |||

| Single | 50 (90.9%) | 42 (75.0%) | 92 (82.9%) |

| Married | 1 (1.8%) | 2 (3.6%) | 3 (2.7%) |

| Partnered | 2 (3.6%) | 8 (14.3%) | 10 (9.0%) |

| Divorced | 2 (3.6%) | 4 (7.1%) | 6(5.4%) |

| Have a computer at home, n (%) | 51 (92.7%) | 52 (91.2%) | 103 (92.0%) |

The intervention and control groups had no significant differences in recruitment (>75% in each group were recruited online, and <25% were recruited offline from local organizations and referrals). A total of 105 participants (93.8%) completed the follow-up survey.

Table 2 summarizes participant acceptance and engagement (communicating through chat, wall posts, and private messages) over the three 4-week assessment periods. As expected, participation was highest during the first period across all 3 activities. Participation and engagement was high across all 3 assessment periods for the intervention (95%, 91%, and 77%, respectively) and control (73%, 62%, and 55%, respectively) groups.

Table 2.

Participation/Engagement Over Assessment Periods *

| Period 1

|

Period 2

|

Period 3

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (n= 55) | Intervention (n = 57) | Control (n= 55) | Intervention (n = 57) | Control (n= 55) | Intervention (n = 57) | |

|

|

|

|

||||

| Number of participants who responded to: | ||||||

| Message | 38 (69.1%) | 54 (94.7%) | 34 (61.8%) | 52 (91.2%) | 30 (54.5%) | 44 (77.2%) |

| Wall post | 40 (72.7%) | 39 (68.4%) | 34 (61.8%) | 26 (45.6%) | 28 (50.9%) | 27 (47.4%) |

| Chat | 14 (25.5%) | 43 (75.4%) | 11 (20.0%) | 41 (71.9%) | 11 (20.0%) | 36 (63.2%) |

Values reported are numbers (percentages) of participants who responded to the method of communication.

Table 3 presents between-group differences in HIV test requests, returned tests, and follow-up for each group and overall. More intervention participants requested an HIV testing kit than control participants (25 of 57 [44%] vs. 11 of 55 [20%]; mean difference, 24 percentage points [95% CI, 8 to 41 percentage points]). For comparison purposes, a separate analysis using mixed-effects logistic regression gave consistent results. Adjusted regressions that included age and marital status did not change the conclusion.

Table 3.

Group Differences in Requests for HIV Testing Kits, Returned Tests, and Follow-Up for Results Among MSM

| Group | Requested HIV Testing Kit | Returned Test | Followed Up for Test Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention group, n (%) | |||

| Group 1 (n=28) | 14 (50.0) | 5 (17.9) | 4 (14.3) |

| Group 2 (n=29) | 11 (37.9) | 4 (13.8) | 4 (13.8) |

| Overall (n = 57) | 25 (43.9) | 9 (15.8) | 8 (14.0) |

| Control Group, n (%) | |||

| Group 1 (n = 28) | 7 (25.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Group 2 (n = 27) | 4 (14.8) | 2 (7.4) | 0 (0.0) |

| Overall (n = 55) | 11 (20.0) | 2 (3.6) | 0 (0.0) |

MSM = men who have sex with men.

Because of the sparse data on returned tests and follow-up for test results, statistical analyses of these outcomes are not presented. Of the 25 intervention participants who requested a testing kit, 9 returned it and 8 of them followed up to obtain their test results. Of the 11 control participants who requested a testing kit, 2 returned it but neither followed up to obtain their test results.

Table 4 shows social media use and sexual risk behavior by group. The median number of sexual partners within 3 months decreased from baseline to follow-up among the intervention (−2) and control (−1) groups.

Table 4.

Within-Participant Changes From Baseline to Follow-up In Social Media Use and Sexual Risk Behavior Over Assessment Periods

| How often do you go online each day? | Number of times used social networks to talk about sexual behaviors and partners in past 3 months | Number of sexual partners in past 3 months | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Median (min, max) | Change from Baseline* Median (min, max) | Baseline Median (min, max) | Change from Baseline Median (min, max) | Baseline Median (min, max) | Change from Baseline Median (min, max) | |

| Intervention group | ||||||

| Group 1 (n=28) | 4 (2, 6) | 0 (−2, 2) | 0 (0, 20) | 0.5 (−15, 100) | 2.5 (0, 25) | −2 (−15, 3) |

| Group 2 (n=29) | 4 (3, 6) | 0 (−3, 2) | 0 (0, 50) | 4 (−30, 97) | 2 (0, 100) | −1 (−100, 4) |

| Total (n=57)** | 4 (2, 6) | 0 (−3, 2) | 0 (0, 50) | 1.5 (−30, 100) | 2 (0, 100) | −2 (−100, 4) |

| Control group | ||||||

| Group 1 (n=28) | 4 (2, 6) | 0 (−1, 2) | 1.5 (0, 100) | 1 (−50, 100) | 2 (0, 50) | −1 (−21, 5) |

| Group 2 (n=27) | 4 (2, 6) | 0 (−3, 3) | 3 (0, 500) | 0 (−25, 25) | 3 (0, 15) | −1 (−10, 15) |

| Total (n=55)** | 4 (2, 6) | 0 (−3, 3) | 2 (0, 500) | 0 (−50, 100) | 3 (0, 50) | −1 (−21, 15) |

Values represent the medians of the differences between two time points on the 5-point Likert scale (1=0–1 h; 2=1–2 h; 3=3–4 h; 4=4–5 h, 5=> 5 h).

Based on 52 observations in the intervention group (group 1, n = 24; group 2, n =28) and 52 observations in the control group (group 1, n = 27; group 2, n = 25).

DISCUSSION

Among MSM in Los Angeles, a peer-led HIV testing intervention using study-created social networking communities led to high rates of participant engagement and an increase in home-based HIV testing. This study is important for several reasons. First, we believe it is the first randomized, controlled trial of HIV testing that is based on social networking and suggests that social networking can change health behaviors and increase HIV testing among at-risk populations. Second, it suggests that African American and Latino MSM find social networking to be an acceptable and engaging platform for HIV prevention and find home-based testing kits to be an acceptable method of testing. Third, it includes a verifiable behavioral outcome of HIV testing and self-report measures, providing further validity that social networking communities can change HIV-related health behaviors. Fourth, it has 12-week retention rates of more than 93% among minority MSM, suggesting that these methods lead to high rates of participant engagement and can be used to overcome low retention rates typically found in online studies (1). These results are encouraging because a higher proportion of intervention participants than control participants who returned their HIV testing kits and followed up to receive test results.

The active participation of African American and Latino MSM supports research showing that social networking is growing among minority groups and is an acceptable and engaging platform for HIV prevention among at-risk populations (23). African Americans (33%) and English-speaking Latinos (36%) are almost 1.5 times more likely to use social networking sites than the general adult population (23%) (22, 23). In addition, gay, lesbian, and bisexual persons use social networks more than heterosexuals (15). The high rates of requests for home-based HIV testing kits suggest that pairing these kits with HIV interventions involving social networking may be a feasible and acceptable testing method among at-risk, stigmatized groups.

Of note is the greater frequency of chatting and sending personal messages in the intervention group than in the control group. These values were reported by peer leaders rather than observed by the investigators but might provide important information to help explain the effects of the intervention because peer leaders were instructed to use real-time, private methods of communication as a tool for behavior change to prevent HIV.

Our study has limitations. First, it was limited to only 2 Facebook communities per group. Second, participants’ location was self-reported; some participants may have falsely reported being from Los Angeles. Third, because this study was designed to test the feasibility and acceptability of using social networking to increase HIV testing, a control social networking group (focusing on peer-delivered communication about general health) was deemed a more fitting control setting than offline, peer-delivered information on HIV prevention. However, findings about reductions in sexual risk behaviors were similar to those studies in offline HIV intervention using peer leaders (4, 24). Fourth, because many MSM use additional social and sexual networking sites, future research could compare the usefulness of these sites for interventions to prevent HIV. Finally, no established best practice existed for HIV communication using social networking; peer-leader communication style and content therefore varied on the basis of guidance from the trainers. Because this factor may reduce the ability to generalize message content and style, future research can determine best practices for HIV communication using social networking.

Research on the HIV treatment cascade, or the decreasing proportion of HIV-positive persons who receive HIV-related services at each stage of testing, care-seeking, and medication adherence, has shown the importance of targeting HIV identification efforts toward at-risk populations, such as MSM, to increase testing and link HIV-positive persons with care (24, 25). As social networking becomes increasingly prevalent, it will be available for rapid, widespread, and population-focused HIV prevention, testing, and treatment. Data underscore the need to evaluate these innovative technologies for HIV prevention and treatment among at-risk groups.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was graciously supported by funding from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH; Young K01 MH 090884), UCLA CHIPTS, and the UCLA AIDS Institute. Funding agencies played no role in study design, analysis, or manuscript.

The authors wish thank Sheana Bull, PhD, and Simon Rosser, PhD, for their feedback on the study.

Grant Support

National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), (Young K01 MH 090884); UCLA CHIPTS; and the UCLA AIDS Institute Center for AIDS Research (AI 028697).

Footnotes

Reproducible Research Statement: Statistical code and dataset: Not available. Study protocol: Available from Dr. Young (sdyoung@mednet.ucla.edu).

Authors Contributions

Sean Young, conceived of and carried out study, wrote manuscript; William Cumberland statistician, participated in study design and sample size calculations, reviewed and revised the manuscript, and was responsible for estimation of effects; Sung-Jae Lee, statistician and reviewed manuscript; Devan Jaganath, helped carry out intervention and edit manuscript; Greg Szekeres, helped conceive of study and edit manuscript; Thomas Coates, advised on study, reviewed manuscript.

Contributor Information

Sean D. Young, Department of Family Medicine, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

William G. Cumberland, Department of Biostatistics, School of Public Health, University of California, Los Angeles, USA.

Sung-Jae Lee, Department of Psychiatry, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

Devan Jaganath, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

Greg Szekeres, Department of Medicine, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

Thomas Coates, Department of Medicine, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

References

- 1.Hall HI, Song R, Rhodes P, et al. Estimation of HIV Incidence in the United States. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2008;300(5):520–529. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.5.520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Los Angeles County Division of HIV and STD Programs. 2012 Annual HIV Surveillance Report. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rogers E. Diffusion of innovations. 4. New York: Free Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maiorana A, Kegeles S, Fernandez P, et al. Implementation and evaluation of an HIV/STD intervention in Peru. Eval Program Plann. 2007;30(1):82–93. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2006.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kelly J, Murphy D, Sikkema K. Randomised, controlled, community-level HIV-prevention intervention for sexual-risk behaviour among homosexual men in US cities. Lancet. 1997;350:1500–05. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)07439-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lawrence JSS, Brasfield T, Diaz Y, Jefferson K, Reynolds M, Leonard M. Three-year follow-up of an HIV risk-reduction intervention that used popular peers. American Journal of Public Health. 1994;84(12):2027–2028. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.12.2027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bull S, Pratte K, Whitesell N, Rietmeijer C, McFarlane M. Effects of an Internet-Based Intervention for HIV Prevention: The Youthnet Trials. AIDS and Behavior. 2009;13(3):474–487. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9487-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kalichman SC, Benotsch EG, Weinhardt L, Austin J, Luke W, Cherry C. Health-related Internet use, coping, social support, and health indicators in people living with HIV/AIDS: preliminary results from a community survey. Health Psychol. 2003;22(1):111–6. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.22.1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bowen A, Williams M, Daniel C, Clayton S. Internet based HIV prevention research targeting rural MSM: feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2008 Sep 4; doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9171-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McFarlane M, Bull SS, Rietmeijer CA. The Internet as a newly emerging risk environment for sexually transmitted diseases. JAMA. 2000;284(4):443–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.4.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tashima K, Alt E, Harwell J, Fiebich-Perez D, Flanigan T. Internet sex-seeking leads to acute HIV infection: a report of two cases. International Journal of Std & Aids. 2003;14(4):285–6. doi: 10.1258/095646203321264926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Benotsch E, Kalichman S, Cage M. Men who have met sex partners via the Internet: Prevalence, predictors, and implications for HIV prevention. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2002;31(2):177–183. doi: 10.1023/a:1014739203657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosser B. Online HIV prevention and Men’s INternet Study-II (MINTS-II): A glimpse into the world of designing highly-interactive sexual health. Internet-based interventions. World congress for sexology; Montreal, Canada. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Horrigan JB, Smith A. Home Broadband Adoption 2007. Washington, D.C: Pew Internet & American Life Project; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harris Interactive. Gays, Lesbians and Bisexuals Lead in Usage of Online Social Networks. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fox S. Wired for Health: How Californians compare to the rest of the nation: A case study sponsered by the California HealthCare Foundation. Pew Internet and American Life Project. 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith A. Pew Internet and American Life Project. Pew Internet; 2010. Mobile Access 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jaganath D, Gill HK, Cohen AC, Young SD. Harnessing Online Peer Education (HOPE): integrating C-POL and social media to train peer leaders in HIV prevention. AIDS Care. 2011;24(5):593–600. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2011.630355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Young SD. Recommended Guidelines on Using Social Networking Technologies for HIV Prevention Research. AIDS and Behavior. 2012;16(7):1743–1745. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0251-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Young SD, Harrell L, Jaganath D, Cohen AC, Shoptaw S. Feasibility of recruiting peer educators for an online social networking-based health intervention. Health Education Journal. 2013;72(3):276–282. doi: 10.1177/0017896912440768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Home Access Health Corporation. The Home Access HIV-1 Test System. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Young S, Szekeres G, Coates T. The relationship between online social networking and sexual risk behaviors among men who have sex with men (MSM) PLoS ONE. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062271. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith A. Pew Internet American Life Project. Race and Ethnicity: Social Networking. California Immunization Coalition. 2011. Who’s on what: Social media trends among communities of color. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kelly J, Murphy D, Sikkema K. Randomised, controlled, community-level HIV-prevention intervention for sexual-risk behaviour among homosexual men in US cities. Lancet. 1997;350:1500–05. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)07439-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]