Abstract

We previously reported that aldosterone impaired vascular insulin signaling in vivo and in vitro. Fructose-enriched diet induces metabolic syndrome including hypertension, insulin resistance, hyperlipidemia and diabetes in animal. In the current study, we hypothesized that aldosterone aggravated fructose feeding-induced glucose intolerance in vivo. Rats were divided into five groups for six-week treatment; uninephrectomy (Unx, n=8), Unx+aldosterone (aldo, 0.75 μg/h, s.c., n=8), Unx+fructose (fruc, 10% in drinking water, n=8), Unx+aldo+fruc, (aldo+fruc, n=8), and Unx+aldo+fruc+spironolactone, a mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist (aldo+fruc+spiro, 20 mg/kg/day, p.o., n=8). Aldo+fruc rats manifested the hypertension, and induced glucose intolerance compared to fruc intake rats assessed by oral glucose tolerance test, homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp study. Spironolactone, significantly improved the aldosterone-accelerated glucose intolerance. Along with improvement in insulin resistance, spironolactone suppressed upregulated mineralocorticoid receptor (MR) target gene, serum and glucocorticoid-regulated kinases-1 mRNA expression in skeletal muscle in aldo+fruc rats. In conclusion, these data suggested that aldosterone aggravates fructose feeding-induced glucose intolerance through MR activation.

Keywords: Aldosterone, Fructose, Insulin resistance

1. Introduction

Metabolic syndrome and Obesity related diseases are an important and growing health concern not only in the United States but also around the world (Ferder et al., 2010). Most human obesity occurs in the presence of highly palatable foods and calorically sweetened beverages. Attention has been centered on the possible role of foods and drinks with added sugars, especially fructose. Over the past several decades, daily caloric intake has increased, and about 50% of the increased calories have come from the consumption of calorically sweetened beverages (Ferder et al., 2010; Popkin et al., 2006). Fructose has now become a major constituent of our modern diet, especially sweetened beverages. Mounting evidence has shown that chronically high consumption of fructose in rodents leads to insulin resistance, obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and high blood pressure (Basciano et al., 2009; Dong et al., 2010; Tappy and Le, 2010).

The role of aldosterone, a mineralocorticoid hormone, in the pathogenesis of insulin resistance is a growing interest with its receptor, mineralocorticoid receptor (MR). Classically, aldosterone participate in the regulation of blood pressure, water, sodium, and potassium homeostasis through interaction with the MR, which is expressed in target epithelial cells and trigger gene transcription (Connell and Davies, 2005). It has been reported that primary aldosteronism patients frequently showed impaired glucose tolerance (Conn et al., 1964). Previous studies also showed that aldosterone excess in primary aldosteronism is related to impaired glucose homeostasis (Fallo et al., 2012, 2006) as well as insulin resistance (Catena et al., 2006; Stas et al., 2008). In addition, recent data from the aliskiren observation of heart failure treatment (ALOFT) study demonstrated a strong and positive correlation between fasting insulin and both plasma and urinary aldosterone (Freel et al., 2009). Moreover, patients who had aldosterone “escape” from the inhibitory effect of homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) values; consistent with the concept that aldosterone contributes to insulin resistance (Freel et al., 2009). Recent clinical studies found that aldosterone production is associated with insulin resistance in normotensive healthy subjects independent of traditional risk factor (Garg et al., 2010) and high level of aldosterone predicted the development of insulin resistance after 10 years in subjects without insulin resistance at baseline (Kumagai et al., 2011).

MR activation contributes to downstream signaling pathways that attenuate insulin signaling mechanisms in the heart, vasculature, and skeletal muscle that collectively alter the cellular metabolism (Giacchetti et al., 2007). Furthermore, other studies also reported that MR blockade improved insulin sensitivity by changing adiponectin, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ, and proinflammatory adipokines in obese rats (Guo et al., 2008). Studies in animal models of obesity-induced insulin resistance (ob/ob and db/db mice) shown that MR blockade improved glucose tolerance, reduced HOMA levels, and decreased fasting levels of triglycerides (Guo et al., 2008; Hirata et al., 2009). Very recently Selvaraj et al. (2013) reported that excess aldosterone results in glucose intolerance as a result of impaired insulin signal transduction leading to decreased skeletal muscle glucose uptake and oxidation. Recent study in Wistar rats showed that an excessive aldosterone has an adverse effect on glucose uptake in liver and skeletal muscle (Selvaraj et al., 2009) and on skeletal muscle insulin metabolic signaling in TG (mRen2) rats (Lastra et al., 2008). Moreover, previously we reported that aldosterone attenuates glucose metabolism in vascular smooth muscle cells (Hitomi et al., 2007) and very recently our data also clearly showed that aldosterone induces vascular remodeling through insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor- and hybrid receptor-dependent vascular insulin resistance both in vitro and vivo (Sherajee et al., 2012). Accumulating evidences reveals the existence of a vital role of aldosterone for the development of insulin resistance and thus increased incidence of type 2 diabetes. Hoverer, the role of aldosterone in fructose intake induced insulin resistance has not been identified. Present study was performed to test the hypothesis that aldosterone aggravates fructose feeding-induced glucose intolerance in vivo. Therefore, we examined the effects of an MR antagonist, spironolactone on whole body insulin sensitivity in fructose-drinking aldosterone-infused rat model.

2. Materials and methods

All experimental procedures were performed according to the guideline for the care and use of animals established by Kagawa University. Five week old male Sprague-Dawley rats (CLEA Japan, Inc., Shizuoka, Japan) underwent right uninephrectomy (Unx) under anesthesia with sodium pentobarbital (50 mg/kg, i.p.) through flank incision. After one week recovery, rats were randomly treated with one of the following combinations for 6 weeks: group 1, Unx (control, n=8); group 2, Unx+aldosterone (aldo, 0.75 μg/h, s.c, n=8); group 3, Unx+fructose (fruc, 10% in drinking water, n=8); group 4, Unx+aldosterone+fructose (aldo+fruc, n=8); group 5, Unx+aldosterone+fructose+spironolactone (aldo+fruc+spiro, 20 mg/kg/day, p.o., n=8). Before grouping rats were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (50 mg/kg bwt, i.p.), and an osmotic minipump (Alzet®, model 2006, Durect Corp., Cupertino, California, USA) was implanted subcutaneously at the dorsum of the neck to infuse aldosterone. The doses of aldosterone, fructose and spironolactone were determined on the basis of results from previous studies in rats (Nakano et al., 2005; Nishiyama et al., 2004; Suzuki et al., 1997). Animals were fasted for 12 h at the end of the experiment. Then the animals were killed by decapitation, trunk blood was collected in chilled tube contained EDTA. Thereafter soleus muscle tissue was collected and immersed in RNAlater (Sigma-Aldrich) for total RNA extraction (Kobori et al., 2005).

Systolic blood pressure (SBP) was measured in conscious rats by tail-cuff plethysmography (BP-98A; Softron, Tokyo, Japan).

2.1. Oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT)

OGTT was performed 4 day before the animal was killed for sampling. Animals were food restricted over night before OGTT. OGTT was done with a 2 g/kg body weight glucose feeding by gavage. Blood was drawn from a cut at the tip of the tail before and at 15, 30, 60 and 90 min after the glucose feeding and blood glucose was analyzed by glucometer. Whole blood was mixed thoroughly with EDTA and centrifuged to separate the plasma. Plasma samples were analyzed for insulin.

2.2. Homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR)

The HOMA-IR, an index of insulin resistance was calculated by using the following equation: fasting glucose (mmol/L) × fasting insulin (μIU/L)/22.5. Typically, a HOMA-IR value >2 is used to identify significant insulin resistance (Matthews et al., 1985).

2.3. Real-time PCR

The mRNA expressions of glyceraldehydes-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), Sgk1 were analyzed by real-time PCR using a Light Cycler FastStart DNA Master SYBR Green I kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, California, USA). Briefly, cDNA was initially denatured at 95 °C for 30 s, and then amplified by PCR for 40 cycles (95 °C for 15 s, 60 °C for 40 s) (Nagai et al., 2005). Real time PCR was performed using GAPDH primers (F: 5′-TGAACGG-GAAGCTCACTGG-3′ and R: 5′-TCCACCACCCTGTTGCTGTA-3′), Sgk1 primers (F: 5′-TGCATGATCTCGTGATGAC-3′ and R: 5′-AAGTTCTT-CCTGGCCGGTAT-3′ (Nagai et al., 2005) sequences. All data were expressed as the relative differences between Unx and other groups after normalization to GAPDH expression.

2.4. Other analytical procedure

Plasma level of non-esterified fatty acid (NEFA), triglyceride (all kits from Wako Co. Ltd., Osaka, Japan), adiponectin (Rat Adiponectin ELISA Kit; Cyclex Co. Ltd., Japan), and insulin (Rat Insulin ELISA kit; Shibayagi, Gunma, Japan) were measured using commercially available kit.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as mean±S.E.M. Statistical comparisons of differences were performed using one-way analysis of variance combined with the Newman–Keuls post hoc test. A value of P<0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. General profiles and plasma parameter

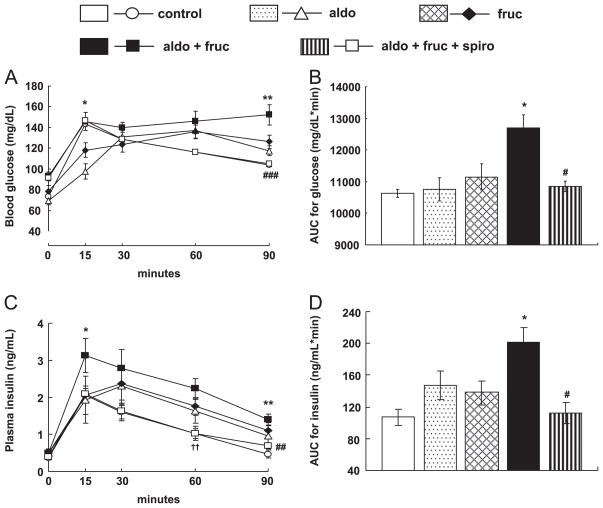

All groups showed increased body weight gain. Fructose intake rats showed non-significant trends to increase in body weight and was non-significantly suppressed by spironolactone treatment. However, there was no significant change in body weight between the groups (Fig. 1A). The temporal profile of SBP is depicted in Fig. 1B. At the beginning of experiment there was no significant difference in basal level of SBP between the groups. Following 6 weeks treatment period, only aldo and fruc rats showed increased SBP compared to control (149±4, 140±4, 112±1 mmHg, respectively). However, the aldo+fruc rats had a significantly higher SBP than that of fruc (165±2 vs. 140±4 mmHg at week 6, respectively). Spironolactone treatment normalized SBP in these animals (118±0.9 at week 6).

Fig. 1.

The profiles of body weight (A) and systolic blood pressure (B). Body weight changes showed no significant difference between the groups. Aldo+fruc rats showed hypertension. Spironolactone administration prevents the development of hypertension. Values are mean±S.E.M. ***P<0.001 vs. fruc; ###P<0.001 vs. aldo+fruc group; †††P<0.001 vs. control. (n=8 in each group).

The data of plasma parameters are summarizes in Table 1. After 6 weeks of treatment there was no significant differences in plasma triglyceride level between fruc and aldo+fruc rats. Spironolactone had no effect on this plasma parameter. On the other hand, aldo+fruc group showed non-significant trends to increased non-esterified fatty acid (NEFA) and to decrease in plasma adiponectin level compared to fruc group. Spironolactone treatment tends to lowered NEFA and to increase the adiponectin level which were not statistically significant.

Table 1.

Effects of aldosterone, fructose and spironolactone on plasma parameters in rats.

| Groups | Plasma triglyceride (mg/dL) | Plasma NEFA (mEq/L) | Plasma adiponectin (ng/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 81±22 | 0.32±0.03 | 4.59±0.29 |

| Aldo | 124±8.5 | 0.24±0.01 | 3.45±0.20 |

| Fruc | 304±41a | 0.34±0.02 | 3.48±0.13 |

| Aldo+fruc | 298±42a | 0.44±0.04 | 3.12±0.18 |

| Aldo+fruc+spiro | 337±17a | 0.32±0.02 | 4.11±0.35 |

At the end of the experiment, plasma triglyceride level was elevated in furc and aldo+fruc treated rats which was unaffected by spironolactone treatment. Plasma NEFA and adiponectin levels showed no significant difference between the groups. NEFA; non-esterified fatty acid, aldo; aldosterone, fruc; fructose, spiro; spirolactone. Values are means±S.E.M. (n=8 in each group).

P<0.05 vs. control group.

3.2. Effects of spironolactone treatment on aldo+fruc induced insulin resistance

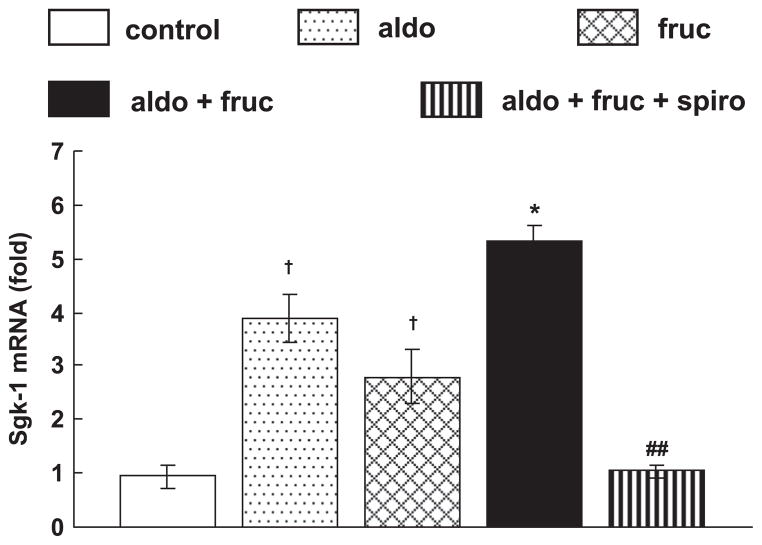

Oral glucose tolerance test was performed to analyzed whole body insulin sensitivity, in which both blood glucose and insulin concentration were determined and their respective area under the curve (AUC) were calculated. Glucose and insulin responses during OGTT in the treated groups are shown in Fig. 2. Compared with the fruc rats the aldo+fruc rats showed higher glucose and insulin levels after administration of oral glucose. Spironolactone treatment attenuated the increase in glucose and insulin levels observed in aldo+fruc rats as shown Fig. 2A and C, respectively. AUC for blood glucose was significantly larger in aldo+fruc rats, and the area under curve for insulin was substantially greater in aldo+fruc rats both of which were significantly decreased by spironolactone (Fig. 2B and D, respectively).

Fig. 2.

Whole body insulin sensitivity was assessed by oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) after overnight fasting. The responses of blood glucose (A), and plasma insulin (C) to oral glucose loading during OGTT and the calculated total areas under curves (AUC) for the blood glucose (B), and plasma insulin (D) responses. Compared to fruc rats, the aldo+fruc treated rats showed higher glucose and insulin levels and their AUC in response to oral glucose loading. Spironolactone treatment prevented the increases in blood glucose and plasma insulin levels and their AUC in aldo+fruc treated rats. Values are mean±S.E.M. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 vs. fruc; # P<0.05 and ###P<0.001 vs. aldo+fruc group; †P<0.05 vs. control group (n=8 in each group).

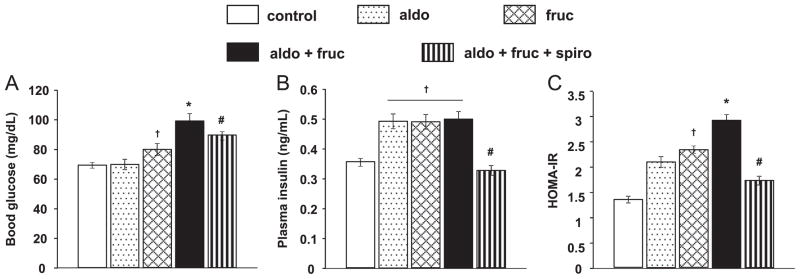

At the end of the study both blood glucose and plasma insulin levels were significantly increase in aldo+fruc rats (Fig. 3A and B, respectively). Fruc rats showed elevated HOMA-IR value compared to control rats and was further aggravated in aldo+fruc rats (Fig. 3C). Spironolactone markedly suppressed the aldo plus fruc-induced increase in fasting glucose, insulin and HOMA-IR value (Fig. 3A–C, respectively).

Fig. 3.

Fasting blood glucose, plasma insulin and homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR). At the end of study, fasting glucose, insulin and HOMA-IR value were elevated in furc and aldo+fruc treated rats. Spironolactone markedly suppressed the aldo plus fruc-induced increase in fasting glucose, insulin and HOMA-IR value. Values are expressed as means±S.E.M. *P<0.05 vs. fruc; #P<0.05 vs. aldo+fruc group; †P<0.05 vs. control group (n=6 in each group).

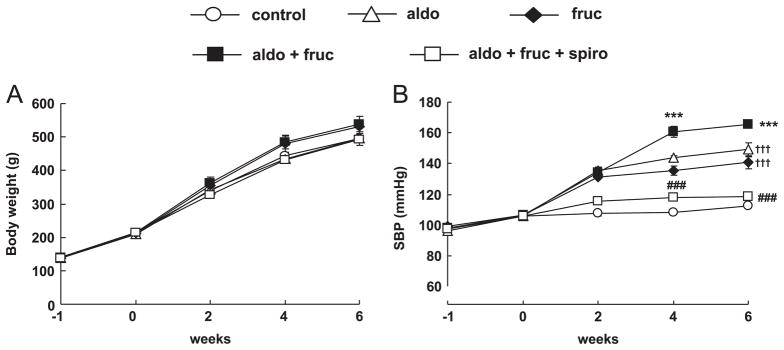

3.3. mRNA expressions in soleus muscle

Next, we evaluated the mineralocorticoid receptor target gene Sgk1 mRNA expression in soleus muscle and we found that Sgk1 mRNA expression was significantly upregulated in aldo+fruc treated soleus muscle compared to fruc rats which was significantly decreased by spironolactone treatment (Fig. 4). Furthermore, there is no change in MR mRNA expression between the groups (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

Soleus muscle mRNA expression of the Sgk-1. The mRNA expression was markedly upregulated in aldo+fruc treated rats. The treatment with spironolactone significantly reduced the upregulated mRNA expression. Values are expressed as means±S.E.M. *P<0.05 vs. fruc; ##P<0.01 vs. aldo+fruc group; †P<0.05 vs. control group (n=8 in each group).

4. Discussion

In the present study, we found that aldosterone markedly enhances plasma glucose and insulin levels after oral glucose administration in fructose fed rats which were ameliorated by MR antagonist spironolactone, suggesting a pivotal role of aldosterone in fructose-induced insulin resistance. Previous study in rats showed that treatment with 10% fructose in drinking water (equivalent to a diet containing 48–57% fructose) for one week or longer is appropriate for the rapid production of fructose induce insulin resistance and hypertension (Dai and McNeill, 1995). Multiple lines of evidence have shown an association between aldosterone and insulin resistance. In addition, clinical reports shown that patients with primary aldosteronism has impaired glucose tolerance as assessed by oral glucose tolerance test (Conn, 1965).

In this study, we first investigated whether aldosterone aggravates insulin resistance in fructose intake rats. After 6 weeks treatment with aldosterone we found that insulin resistance was accelerated in aldo+fruc rats as assed by oral glucose tolerance test (Fig. 2) as well as HOMA-IR (Fig. 3C). We also examined the whole body insulin sensitivity using a hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp method, which revealed that aldo+fruc treated rats showed insulin resistance as indicated by the decreased glucose infusion rate. Glucose infusion rate was decreased in aldo+fruc rat compared to fruc treated rats but not reached statistically significant (data not shown). Insulin resistance is associated with decreased glucose uptake in insulin sensitive tissues such as skeletal muscle, adipose tissue and liver. We also evaluated insulin action using soleus muscle and found that insulin-stimulated glucose uptake in isolated soleus muscle were attenuated in aldo+fruc treated rats compared to fruc rats which was improved by MR blockade, although this result was not statistically significant (data not shown).

Whole body insulin resistance, mainly due to a decreased responsiveness to normal circulating insulin of skeletal muscle has been demonstrated to be associated with systemic conditions such as diabetes, metabolic syndrome and hypertension (Ferrannini and Natali, 1991). In the present study, we evaluate the role of aldosterone as a promoter of insulin resistance in a rat model of fructose induced insulin resistance using the aldosterone blocker, spironolactone. Consistent with previous study in Ren2 rats (Lastra et al., 2008), in the present study spironolactone treatment significantly improved insulin resistance in aldo+fruc rats. Both glucose infusion rate and glucose uptake was improved by spironolactone treatment. In addition, a MR target gene, Sgk1 expression was also upregulated in aldo+fruc rats which was significantly downregulated by spironolactone treatment suggesting the role of mineralocorticoid receptor activation in this pathophysiological condition. Previous study showed that the insulin resistance resulting from fructose feeding is due to the diminished ability of insulin to suppress hepatic glucose output, and not to a decrease in insulin-stimulated glucose uptake by muscle (Tobey et al., 1982). In the present study we found that aldosterone increased Sgk1 mRNA expression in soleus muscle and was suppressed by MR blockade, however, it had no significant effect on glucose uptake suggesting aldosterone accelerated fructose-induced insulin resistance by impairing insulin action in insulin responsive organ other than soleus muscle.

Consistent with previous findings, results from the present study demonstrate that chronic fructose intake results in insulin resistance and significantly increase blood pressure. Aldosterone along with fructose accelerates the insulin resistance and induced hypertension in aldo+fruc rats. The results of the present study support the previous studies in humans demonstrating an association among increased levels of aldosterone, impaired glucose homeostasis, and insulin resistance. Previous studies showed that patients with primary aldosteronism, either tumor induced or idiopathic, manifest a greater insulin response to an oral glucose load as well as reduced systemic insulin sensitivity compared with age-, sex-, and body mass index-matched normotensive patients (Catena et al., 2006). Furthermore, in Primary hyperaldosteronism, removal of an aldosterone-producing adenoma or treatment with a MR antagonist improves insulin sensitivity, further supporting a direct role of aldosterone in mediating systemic insulin resistance (Haluzik et al., 2002). However, in the present study aldosterone infused rats did not demonstrated insulin intolerance as assed by OGTT as well as by clamp test. These results are consistent with previous study (Sherajee et al., 2012). The indiscriminate results of the present study from clinical studies as mentioned above are may be due to short duration of aldosterone infusion in the present study.

Adiponectin, a novel adipose tissue specific cytokine that circulates in plasma at high levels has been demonstrated to increase insulin sensitivity by increasing tissue fat oxidation and decreasing the influx of free fatty acid into the liver (Chandran et al., 2003), reducing the intracellular triglyceride content in the liver and muscle (Diez and Iglesias, 2003), suppressing the hepatic glucose output, and increasing the muscular glucose utilization (Chandran et al., 2003). In the present study we also found that plasma adiponectin level was decreased in aldo+fruc rats which were improved by spironolactone treatment (Table1). This result is in consistent with previous report showing an increase in circulating adiponectin levels in diabetic individuals with poor glycemic control treated with spironolactone (Matsumoto et al., 2006).

In conclusion, the present investigation has demonstrated that aldosterone aggravate insulin resistance in fructose intake rats through MR activation.

References

- Basciano H, Miller AE, Naples M, Baker C, Kohen R, Xu E, Su Q, Allister EM, Wheeler MB, Adeli K. Metabolic effects of dietary cholesterol in an animal model of insulin resistance and hepatic steatosis. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2009;297:E462–473. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90764.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catena C, Lapenna R, Baroselli S, Nadalini E, Colussi G, Novello M, Favret G, Melis A, Cavarape A, Sechi LA. Insulin sensitivity in patients with primary aldosteronism: a follow-up study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:3457–3463. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandran M, Phillips SA, Ciaraldi T, Henry RR. Adiponectin: more than just another fat cell hormone? Diabetes Care. 2003;26:2442–2450. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.8.2442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conn JW. Hypertension, the potassium ion and impaired carbohydrate tolerance. N Engl J Med. 1965;273:1135–1143. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196511182732106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conn JW, Knopf RF, Nesbit RM. Clinical characteristics of primary aldosteronism from an analysis of 145 cases. Am J Surg. 1964;107:159–172. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(64)90252-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connell JM, Davies E. The new biology of aldosterone. J Endocrinol. 2005;186:1–20. doi: 10.1677/joe.1.06017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai S, McNeill JH. Fructose-induced hypertension in rats is concentration-and duration-dependent. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods. 1995;33:101–107. doi: 10.1016/1056-8719(94)00063-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diez JJ, Iglesias P. The role of the novel adipocyte-derived hormone adiponectin in human disease. Eur J Endocrinol. 2003;148:293–300. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1480293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong B, Wu M, Li H, Kraemer FB, Adeli K, Seidah NG, Park SW, Liu J. Strong induction of PCSK9 gene expression through HNF1alpha and SREBP2: mechanism for the resistance to LDL-cholesterol lowering effect of statins in dyslipidemic hamsters. J Lipid Res. 2010;51:1486–1495. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M003566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallo F, Pilon C, Urbanet R. Primary aldosteronism and metabolic syndrome. Horm Metab Res. 2012;44:208–214. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1295412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallo F, Veglio F, Bertello C, Sonino N, Della Mea P, Ermani M, Rabbia F, Federspil G, Mulatero P. Prevalence and characteristics of the metabolic syndrome in primary aldosteronism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:454–459. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferder L, Ferder MD, Inserra F. The role of high-fructose corn syrup in metabolic syndrome and hypertension. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2010;12:105–112. doi: 10.1007/s11906-010-0097-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrannini E, Natali A. Essential hypertension, metabolic disorders, and insulin resistance. Am Heart J. 1991;121:1274–1282. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(91)90433-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freel EM, Tsorlalis IK, Lewsey JD, Latini R, Maggioni AP, Solomon S, Pitt B, Connell JM, McMurray JJ. Aldosterone status associated with insulin resistance in patients with heart failure—data from the ALOFT study. Heart. 2009;95:1920–1924. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2009.173344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garg R, Hurwitz S, Williams GH, Hopkins PN, Adler GK. Aldosterone production and insulin resistance in healthy adults. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:1986–1990. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-2521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giacchetti G, Ronconi V, Turchi F, Agostinelli L, Mantero F, Rilli S, Boscaro M. Aldosterone as a key mediator of the cardiometabolic syndrome in primary aldosteronism: an observational study. J Hypertens. 2007;25:177–186. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3280108e6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo C, Ricchiuti V, Lian BQ, Yao TM, Coutinho P, Romero JR, Li J, Williams GH, Adler GK. Mineralocorticoid receptor blockade reverses obesity-related changes in expression of adiponectin, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma, and proinflammatory adipokines. Circulation. 2008;117:2253–2261. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.748640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haluzik M, Sindelka G, Widimsky J, Jr, Prazny M, Zelinka T, Skrha J. Serum leptin levels in patients with primary hyperaldosteronism before and after treatment: relationships to insulin sensitivity. J Hum Hypertens. 2002;16:41–45. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirata A, Maeda N, Hiuge A, Hibuse T, Fujita K, Okada T, Kihara S, Funahashi T, Shimomura I. Blockade of mineralocorticoid receptor reverses adipocyte dysfunction and insulin resistance in obese mice. Cardiovasc Res. 2009;84:164–172. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hitomi H, Kiyomoto H, Nishiyama A, Hara T, Moriwaki K, Kaifu K, Ihara G, Fujita Y, Ugawa T, Kohno M. Aldosterone suppresses insulin signaling via the downregulation of insulin receptor substrate-1 in vascular smooth muscle cells. Hypertension. 2007;50:750–755. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.093955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobori H, Ozawa Y, Suzaki Y, Nishiyama A. Enhanced intrarenal angiotensinogen contributes to early renal injury in spontaneously hypertensive rats. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:2073–2080. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004080676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumagai E, Adachi H, Jacobs DR, Jr, Hirai Y, Enomoto M, Fukami A, Otsuka M, Kumagae S, Nanjo Y, Yoshikawa K, Esaki E, Yokoi K, Ogata K, Kasahara A, Tsukagawa E, Ohbu-Murayama K, Imaizumi T. Plasma aldosterone levels and development of insulin resistance: prospective study in a general population. Hypertension. 2011;58:1043–1048. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.180521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lastra G, Whaley-Connell A, Manrique C, Habibi J, Gutweiler AA, Appesh L, Hayden MR, Wei Y, Ferrario C, Sowers JR. Low-dose spironolactone reduces reactive oxygen species generation and improves insulin-stimulated glucose transport in skeletal muscle in the TG (mRen2) 27 rat. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2008;295:E110–116. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00258.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews DR, Hosker JP, Rudenski AS, Naylor BA, Treacher DF, Turner RC. Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and b-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia. 1985;28:412–419. doi: 10.1007/BF00280883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto S, Takebayashi K, Aso Y. The effect of spironolactone on circulating adipocytokines in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus complicated by diabetic nephropathy. Metabolism. 2006;55:1645–1652. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2006.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagai Y, Miyata K, Sun GP, Rahman M, Kimura S, Miyatake A, Kiyomoto H, Kohno M, Abe Y, Yoshizumi M, Nishiyama A. Aldosterone stimulates collagen gene expression and synthesis via activation of ERK1/2 in rat renal fibroblasts. Hypertension. 2005;46:1039–1045. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000174593.88899.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakano S, Kobayashi N, Yoshida K, Ohno T, Matsuoka H. Cardioprotective mechanisms of spironolactone associated with the angiotensin-converting enzyme/epidermal growth factor receptor/extracellular signal-regulated kinases, NAD(P)H oxidase/lectin-like oxidized low-density lipoprotein receptor-1, and Rho-kinase pathways in aldosterone/salt-induced hypertensive rats. Hypertens Res. 2005;28:925–936. doi: 10.1291/hypres.28.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishiyama A, Yao L, Nagai Y, Miyata K, Yoshizumi M, Kagami S, Kondo S, Kiyomoto H, Shokoji T, Kimura S, Kohno M, Abe Y. Possible contributions of reactive oxygen species and mitogen-activated protein kinase to renal injury in aldosterone/salt-induced hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 2004;43:841–848. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000118519.66430.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popkin BM, Armstrong LE, Bray GM, Caballero B, Frei B, Willett WC. A new proposed guidance system for beverage consumption in the United States. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83:529–542. doi: 10.1093/ajcn.83.3.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selvaraj J, Muthusamy T, Srinivasan C, Balasubramanian K. Impact of excess aldosterone on glucose homeostasis in adult male rat. Clin Chim Acta. 2009;407:51–57. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2009.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selvaraj J, Sathish S, Mayilvanan C, Balasubramanian K. Excess aldosterone-induced changes in insulin signaling molecules and glucose oxidation in gastrocnemius muscle of adult male rat. Mol Cell Biochem. 2013;372:113–126. doi: 10.1007/s11010-012-1452-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherajee SJ, Fujita Y, Rafiq K, Nakano D, Mori H, Masaki T, Hara T, Kohno M, Nishiyama A, Hitomi H. Aldosterone induces vascular insulin resistance by increasing insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor and hybrid receptor. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012;32:257–263. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.240697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stas S, Whaley-Connell AT, Sowers JR. Aldosterone and hypertension in the cardiometabolic syndrome. J Clin Hypertens. 2008;10:94–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2008.08082.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki M, Nomura C, Odaka H, Ikeda H. Effect of an insulin sensitizer, pioglitazone, on hypertension in fructose-drinking rats. Jpn J Pharmacol. 1997;74:297–302. doi: 10.1254/jjp.74.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tappy L, Le KA. Metabolic effects of fructose and the worldwide increase in obesity. Physiol Rev. 2010;90:23–46. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00019.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobey TA, Mondon CE, Zavaroni I, Reaven GM. Mechanism of insulin resistance in fructose-fed rats. Metabolism. 1982;31:608–612. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(82)90100-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]