Background: Mouse dendritic cells can transform their vesicular late endosomes into long tubules, essential for MHC Class II transport.

Results: In human dendritic cells, late endosome tubules are induced by TLR ligation, and for recycling endosomes additional T cell-mediated ICAM-1 and MHC Class I ligation. Tubulation accompanies antigen cross-presentation.

Conclusion: Human dendritic cells transform endosomal compartments upon distinct triggers.

Significance: Induced endosomal tubules regulate human dendritic cell functioning.

Keywords: Cell-Cell Interaction, Dendritic Cells, Endosomes, Intracellular Trafficking, T Cell Receptor, Toll-like Receptor (TLR), Live Cell Confocal Microscopy, Recycling, Tubulation, Cross-presentation

Abstract

Mouse dendritic cells (DCs) can rapidly extend their Class II MHC-positive late endosomal compartments into tubular structures, induced by Toll-like receptor (TLR) triggering. Within antigen-presenting DCs, tubular endosomes polarize toward antigen-specific CD4+ T cells, which are considered beneficial for their activation. Here we describe that also in human DCs, TLR triggering induces tubular late endosomes, labeled by fluorescent LDL. TLR triggering was insufficient for induced tubulation of transferrin-positive endosomal recycling compartments (ERCs) in human monocyte-derived DCs. We studied endosomal remodeling in human DCs in co-cultures of DCs with CD8+ T cells. Tubulation of ERCs within human DCs requires antigen-specific CD8+ T cell interaction. Tubular remodeling of endosomes occurs within 30 min of T cell contact and involves ligation of HLA-A2 and ICAM-1 by T cell-expressed T cell receptor and LFA-1, respectively. Disintegration of microtubules or inhibition of endosomal recycling abolished tubular ERCs, which coincided with reduced antigen-dependent CD8+ T cell activation. Based on these data, we propose that remodeling of transferrin-positive ERCs in human DCs involves both innate and T cell-derived signals.

Introduction

Endocytosis and recycling of lipids and receptor-bound proteins in the plasma membrane are highly dynamic and organized processes (1). Engulfed material enters the endosomal pathway, first localizing to early endosomes. From here, most cargo is recycled back to the cell surface via two main recycling pathways that each consists of vesicular and tubular structures. The fast recycling route recycles cargo directly from early endosomes to the plasma membrane, whereas slow recycling occurs via a juxtanuclear-positioned endocytic recycling compartment (ERC)2 (2). Nonrecycled cargo in early endosome transits into late endosomes (LEs) that eventually fuse with lysosomes where remaining cargo is degraded (3).

Activation of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells requires presentation of peptide-MHC complexes of the appropriate specificity. Dendritic cells (DCs) are the most adept antigen-presenting cells. Presentation of extracellular antigens requires antigens to be internalized into endosomes, their processing into peptides, assembly of antigenic peptide-MHC complexes, and transport of these complexes to the cell surface. Whereas loading of exogenous antigen-derived peptides onto Class II MHC molecules occurs in LE, the loading of Class I MHC molecules occurs in the endoplasmic reticulum or, as recent work supports, in endosomal compartments (4–6).

Encounter of antigen-specific CD4+ T cells induces the formation of late endosomal Class II MHC-positive tubules in murine DCs. These intracellular tubules extend approximately to 5–15 μm in length (7–11). The LE tubules transform in a TLR-dependent manner and rearrange transport of Class II MHC molecules between LEs and the DC surface, presumed to facilitate the ensuing CD4+ T cell response (7, 8, 10, 12). In early studies, next to LE tubules also elongated tubular recycling endosomes are observed. In HeLa cervical cancer cells, infection by Salmonella typhimurium or overexpression of Eps 15 homology domain 1 induces formation of these long endosomal tubules (13, 14). These recycling endosome tubules mediate efficient Class I MHC recycling toward the cell surface (14). For human DCs, morphology of the endosomal pathway and signals that induce rearrangement of endosomal structures during immune activation are not understood. We used live cell confocal microscopy to investigate endosomal remodeling in human DCs stimulated with TLR ligands and upon cognate interaction with CD8+ T cells. We demonstrate three modes of inducing endosomal tubulation, triggered by distinct signals for tubular remodeling of late and recycling endosomes. Live cell confocal microscopy experiments reveal an unexpected role for intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) and Class I MHC molecules in remodeling of the endosomal recycling compartment.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

In Vitro Generation of Human Monocyte-derived DCs

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were isolated from healthy donors after informed consent by centrifugation (2300 rpm, 20 min, room temperature) on Ficoll-paque (GE Healthcare). Monocytes were isolated from peripheral blood mononuclear cells by centrifugation (2900 rpm, 45 min, room temperature) on three-layer isotonic Percoll density gradient (from top to bottom: 34, 47.5, and 60%; Sigma-Aldrich). Monocytes were stored in freeze medium (10% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO); Sigma-Aldrich) in heat-inactivated FCS) at −80 °C for maximally 8 weeks.

Monocytes were cultured in 8 wells Nunc Lab-Tek II chambered coverglass (Thermo Scientific). These were precoated with 1% (w/v) Alcian blue 8GX (Klinipath) in PBS for 30 min at 37 °C. Cells were maintained in a humidified incubator at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 5 days in differentiation medium: RPMI 1640 medium with 1% (v/v) PenStrep (Invitrogen), 1% (v/v) GlutaMAX (Invitrogen), and 10% (v/v) human AB+ serum (Sanquin) + 500 units/ml GM-CSF and 100 units/ml IL4 (Immunotools).

Monocyte-derived DC Maturation

MoDC maturation was induced by the addition of 200 ng/ml Lipopolysaccharide Ultrapure from Escherichia coli strain 0111:B4 (LPS-EB ultrapure; Invitrogen), 5 μg/ml polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid (poly(I:C)) (Sigma-Aldrich) 4 h prior to microscope analysis. This occurred in the presence or absence of viral antigens; 3 μg/ml HCMV-derived pp65 antigen (Miltenyi Biotec) or dialyzed recombinant EB2 protein.

Confocal Microscopy and Imaging Analysis

Mature moDCs were washed with RPMI 1640 medium without phenol red, supplemented with 0.2% v/v bovine serum albumin (BSA) (Roche Applied Science) and 10 mm HEPES, and subsequently incubated for 30 min at 37 °C with 20 μg/ml DiI-conjugated LDL (Biomedical Technologies) and 5 μg/ml Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated transferrin (Tfn) (Invitrogen Molecular Probes). Thereafter, cells were washed twice with RPMI 1640 medium without phenol red, supplemented with 0.2% BSA and 10 mm HEPES, and used for live cell imaging. Prior to any stimulation, at least 10 positions were chosen and locked to be able to track the exact same cells over time. Scoring was done for the presence of motile LDL or Tfn-positive tubular structures emanating from the center of moDCs, by two independent observers in a double-blinded manner. The percentage of LDL+ tubular moDCs was relative to LDL-loaded moDCs, whereas Tfn+ tubular moDCs were determined relative to LDL+ tubular moDCs. Live cell imaging was performed on a Zeiss LSM710 confocal microscope equipped with live cell chamber device to maintain 37 °C and 5% CO2 condition during experiments. Images were obtained with a 1.3× optical zoom using Plan-Apochromat 63× 1.40 oil differential interference contrast M27 objective (Zeiss) and processed using Zen 2009 software (Zeiss Enhanced Navigation).

T Cell Clone Antibody-blocking Experiments

HLA-A*0201-restricted, HCMV pp65-specific CD8+ T cell clones were prepared as published (15). HLA A2/NLVPMVATV-restricted CD8+ T cell clones were freshly thawed and incubated in ice-cold PBS at 4 °C for 1 h in the presence or absence of 1 μg/ml mouse anti-human CD11a antibody (anti-LFA-1, HI111; BioLegend) or mouse anti-human CD127 antibody (purified in house from R34-34 hybridoma).

T cells were washed with ice-cold RPMI 1640 medium without phenol red, supplemented with 0.2% BSA and 10 mm HEPES, and kept on ice. Five min prior to incubation with moDCs, T cells were warmed up to 37 °C and used for live cell confocal microscopy.

Beads-Antibody Coating and Bead Binding Assays

Dynabeads® M-450 Epoxy beads (Dynal) were coated with mouse anti-human CD19-biotin antibody (HIB19; BD Biosciences), or mouse anti-human CD54-biotin (ICAM-1) antibody (HA58, eBioscience), or mouse anti-human HLA-A2 (Thermo Scientific Pierce), or a combination of both anti-ICAM-1 and anti-HLA-A2 antibodies, according to the manufacturers' instructions. For imaging experiments, beads were warmed up to 37 °C prior to administration.

Pharmacological Inhibition of Endosomal Remodeling

Human moDCs (day 5) were pulsed for 4 h with 3 μg of pp65 in the presence of 200 ng/ml LPS and 5 μg/ml poly(I:C). Upon staining of ERCs (30 min, 37 ºC) with 5 μg/ml Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated Tfn, vesicle-to-tubule transformation was stimulated by co-culture of antigen-specific (NLVPMVATV) CD8+ T cells for 1 h. MoDC with tubular ERCs were imaged prior to any stimulation and 20–40 min after administration of either 50 μm primaquine biphosphate (Sigma-Aldrich), 10 μm nocodazole (Sigma-Aldrich), PBS, or DMSO (Sigma-Aldrich).

Pharmacological Inhibition of Antigen Cross-presentation

Human moDCs (day 5) were loaded with 3 μg/ml CMV pp65 antigen or NLVPMVATV-peptide (Pepscan) overnight in the presence of 200 ng/ml LPS and 5 μg/ml poly(I:C). Subsequently, moDCs were exposed for 30 min to either primaquine biphosphate (50 μm), or nocodazole (10 μm), or carrier controls PBS and DMSO, respectively (all Sigma-Aldrich). Thereafter, DC cultures were washed thoroughly to remove inhibitors. HLA-A2/NLVPMVATV-restricted CD8+ T cells were added, and DC/CD8+ T cells were co-cultured for a further 5 h at 37 °C. Activation of CD8+ T cells was measured by induced antigen-driven production of IFNγ and TNF, and surface-expressed LAMP1 by flow cytometry. DC viability was determined by Annexin V and 7-AAD staining (Biosciences). Surface expression was determined by staining DC with fluorchrome-conjugated anti-HLA-A2, CD80 (both Biosciences), HLA-DR and ICAM-1 (both BioLegend).

Statistics

Flow cytometry data were collected on FacsCanto II and analyzed with BD FACSDiva v6.1.3 and Flowjo 7.6 software (Treestar). All data were statistically analyzed and plotted with GraphPad Prism 5 software. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

TLR Stimulation of Human Dendritic Cells Triggers Remodeling of Late Endosomes into Tubular Structures

LPS stimulation of murine DCs induced elongated tubular structures emanating from LEs in a time- and dose-dependent manner (7–11). To examine the effect of TLR triggering in LE remodeling of human DCs, we cultured moDCs (5-day culture in the presence of IL4 and GM-CSF (15)) and performed live cell confocal microscopy. To allow visualization of LE, DCs were pulsed with fluorescently labeled DiI-LDL (30 min, 37 °C (7)), followed by washes to remove unbound LDL.

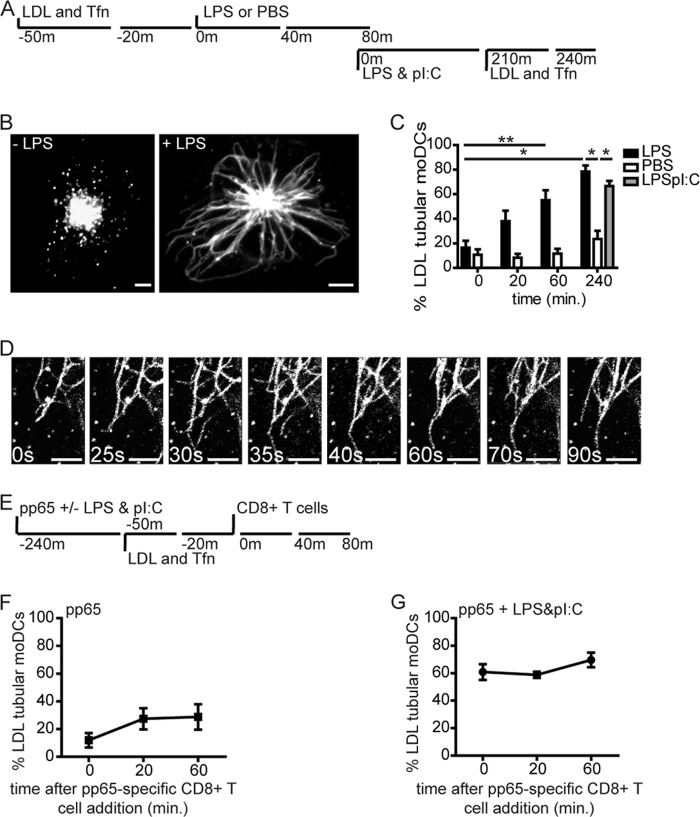

We visualized DiI-LDL-pulsed moDCs after the addition of TLR4 ligand LPS, or PBS as control, in a time-lapse manner (500,000 DCs/coverslip well, LPS 200 ng/ml; 0, 20, 60, and 240 min, schematically depicted in Fig. 1A). Scoring was done for the presence of motile LDL-positive tubular structures emanating from the center of moDCs, by two independent observers in a double-blinded manner. LPS treatment induced a rapid and steady increase in long tubular endosomes in the majority of moDCs (55% of DCs at 1 h, 80% of DCs at 4 h; Fig. 1, B and C). PBS-treated DCs never showed tubular endosomes in >25% of DCs, a background level that may relate to spontaneous DC maturation.3

FIGURE 1.

TLR stimulation of human dendritic cells triggers remodeling of late endosomes into tubular structures. A, schematic outline of live cell confocal microscopy experiment in B and C. Fluorescent cargo LDL-DiI and Tfn-Alexa Fluor 647 were stained after 30-min incubation the late and recycling endosomes, respectively, just before or after stimulation with LPS or PBS. B, confocal image of moDCs with vesicular (left) or tubular (right) LDL+ endosomes (60 min 37 °C, 200 ng/ml LPS). C, percentage of moDCs expressing tubular LDL+ endosomes. Time points indicate a 20-min time window immediately before treatment and around indicated time points (20, 60 min); PBS (white bars), 200 ng/ml LPS (black bars), or mix of 200 ng/ml LPS and 5 μg/ml poly(I:C) (gray bars). Data represent mean ± S.E. (error bars) of four independent experiments. D, time-lapse captures of tubular LDL+ endosomes in LPS-treated moDCs. Time points indicate seconds. E, schematic outline of live cell confocal microscopy experiment in F and G. F and G, percentage of moDCs expressing tubular LDL+ endosomes after culture in the presence of pp65 (3 μg of antigen, 4-h time point) and pp65-specific CD8+ T cells (1:1 ratio) in the absence (F) or presence of LPS and poly(I:C) combined (G). Data represent mean ± S.E. of at least three independent experiments using two-tailed Mann-Whitney U test. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01. Scale bars, 5 μm.

Poly(I:C)-LPS combined treatment induced a level of tubular endosomes similar to LPS treatment alone, measured after 4 h. Of note, moDC-expressed tubular endosomes were stable yet dynamic structures that lasted at least 6 h, or the duration of experiments (Fig. 1D, individual tubules time-lapse captures, and supplemental Movie 1).

Late Endosome Tubular Remodeling in Human Dendritic Cells Occurs Independently of Cognate T Cell Interaction

Cognate DC-T cell interaction induces T cell-polarized tubular endosomes in murine DCs, in a TLR-dependent manner (7, 8). We now asked whether in human moDCs, cognate T cell interaction in itself causes tubulation of LE or that TLR triggering is required. Therefore we pulsed 5-day moDCs with human CMV protein pp65 that is cross-presented to HLA-A2/NLVPMVATV-specific CD8+ T cell clones (15). We then added PBS or TLR ligands LPS and poly(I:C) (200 ng/ml and 5 μg/ml, respectively; 4 h). Next, DCs were pulsed with DiI-LDL for 30 min (according to the scheme in Fig. 1E), to allow for visualization of LE compartments. DCs were washed, T cells were added (1:1 DC:T cell ratio), and DCs were assayed for development of tubular endosomes by time-lapse confocal microscopy (0, 20, and 60 min after the T cell addition). Cognate DC-CD8+ T cell interaction in the absence of LPS-poly(I:C) could not significantly induce LE tubular remodeling (Fig. 1F), indicating the crucial role of TLR ligation in LE tubulation. In contrast, we observed tubular LDL+ compartments in 60–70% of antigen-laden LPS-poly(I:C)-treated DCs. The fraction of antigen-laden DCs expressing tubular LDL+ endosomes did not significantly increase further upon addition of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells (Fig. 1G). In conclusion, TLR-induced formation of tubular endosomes is conserved between murine and human DCs. We found no effect of additional antigen-specific CD8+ T cell contact on LE remodeling as in contrast to the addition of antigen-specific CD4+ T cells in murine DCs (8).

Efficient Tubular Remodeling of Recycling Endosome in Human Dendritic Cells Requires Cognate T Cell Interaction

Does antigen-specific T cell contact perhaps trigger tubular remodeling of other endosomal compartments in human DCs? To address this question, we visualized within moDCs the juxtanuclear located ERC, which is characterized by the presence of Tfn receptors (16). Endosomal recycling can occur via tubular recycling endosomes extending intracellular, as shown in Eps 15 homology domain 1-overexpressing system within HeLa cells. These elongated recycling endosomes facilitate efficient recycling of both Tfn and Class I MHC molecules (14).

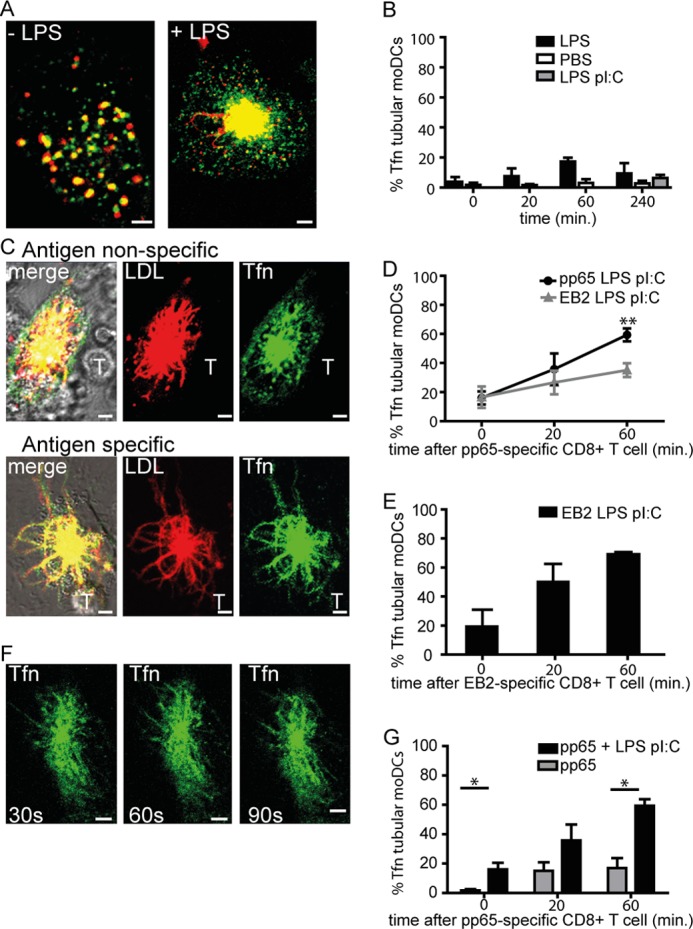

We visualized ERC in moDCs by incorporation of fluorescent Tfn (according to the scheme shown in Fig. 1A). Prior to stimulation, most moDCs have a vesicular Tfn+ ERC (Fig. 2A). In contrast to LE compartments, the addition of LPS or a combination of LPS and poly(I:C) in the absence (Fig. 2B) or presence of viral antigens pp65 (Fig. 2D) or EB2 (Fig. 2E) to moDCs did not induce significant vesicular-to-tubular transformation of the ERC. When pp65-specific CD8+ T cells were added to pp65-laden LPS-poly(I:C)-treated moDCs, tubular transformation of Tfn+ compartments ensued in 60% of LDL-tubular moDCs (Fig. 2, C and D). Similar results are obtained by using EB2-specific CD8+ T cell clone and EB2-laden LPS-poly(I:C)-treated moDCs (Fig. 2E). Incubating EB2-laden LPS-poly(I:C)-treated moDCs with pp65-specific CD8+ T cells, avoiding cognate DC-T cell interaction, showed significantly reduced induction of tubular Tfn+ endosomes compared with Tfn+ tubulating pp65-laden DCs (Fig. 2, C and D, 60 min after the addition of pp65-specific CD8+ T cells).

FIGURE 2.

Efficient recycling endosome tubular remodeling in human dendritic cells requires cognate T cell interaction. A, representative images of moDCs with LDL+ late endosomes (red) and Tfn+ recycling endosomes (green) in the absence or presence of LPS stimulation (60 min, 200 ng/ml). B, percentage of LDL+ tubular moDCs expressing tubular Tfn+ endosomes prior to stimulation (t = 0) or approximately at the indicated time points. Black bars, 200 ng/ml LPS; gray bars, mix of 200 ng/ml LPS and 5 μg/ml poly(I:C). Data represent mean ± S.E. (error bars) of at least three independent experiments. C, representative images of moDCs upon CD8+ T cell contact in antigen-independent (upper images) or antigen-dependent manner (lower images). Red, LDL; green, Tfn; yellow, co-localization of LDL and Tfn; T, pp65-specific CD8+ T cell. D, percentage of LDL+ tubular moDCs expressing tubular Tfn+ endosomes after 4-h culture in the presence of 3 μg HCMV-derived pp65/LPS/poly(I:C) (black circles) or EBV-derived EB2-LPS-poly(I:C) (gray triangles) at the indicated time points. Two-tailed, Mann-Whitney U test p < 0.01 was used. Data represent mean ± S.E. of at least four independent experiments. E, percentage of LDL+ tubular moDCs expressing tubular Tfn+ endosomes after 4-h culture in the presence of 3 μg of EBV-derived EB2 with LPS and poly(I:C) (black circles) at the indicated time points. Data represent mean ± S.E. of at least three independent experiments. F, time-lapse captures of Tfn+ tubular endosomes in moDCs (time points indicate seconds). Scale bars, 5 μm. G, percentage of LDL+ tubular moDCs expressing tubular Tfn+ endosomes upon culture in the presence of 3 μg of HCMV antigen pp65 (4 h) in the absence (gray bars) or presence of LPS-poly(I:C) (black bars). Data represent mean ± S.E. of at least three independent experiments; *, p < 0.05.

In conclusion, TLR signaling alone is not sufficient to drive remodeling of Tfn+ ERC. Instead, functional cognate DC-CD8+ T cell interaction induces remodeling into elongated Tfn+ tubular structures. This remodeling requires TLR stimulation, as tubular transformation did not occur when pp65 antigen-specific CD8+ T cells were cultured with pp65-laden moDCs in the absence of TLR stimulation (Fig. 2G). The TLR-dependent remodeling of Tfn+ compartments in moDCs upon cognate interaction of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells is rapid and dynamic (Fig. 2F and supplemental Movie 2).

ICAM-1 Clustering Provokes Tubulation of Tfn+ Endosomal Recycling Compartments in Human Dendritic Cells

Efficiency of tubular remodeling of Tfn+ ERC is higher upon cognate moDC-CD8+ T cell interaction compared with antigen-independent DC-CD8+ T cell interaction. We hypothesized that interaction of DC-expressed ICAM-1 with lymphocyte function-associated antigen 1 (LFA-1) on interacting T cells facilitates tubulation of Tfn+ ERC in human moDCs for the following reasons. First, TLR4 ligation stimulates surface expression of ICAM-1 within a few hours.3 Second, when antigen-bearing DCs enter the lymph node and are scanned by T cells, the initial DC-T cell interaction is antigen-independent and involves association of LFA-1 with ICAM-1 (17). Third, upon recognition of peptide MHC complexes by antigen-specific T cell receptors (TCRs), TCR signaling drives LFA-1 in a state that binds with increased affinity to ICAM-1 (18). Of additional consideration was that ICAM-1 clustering facilitates antigen presentation by recruiting HLA-A2 to the T cell contact zone (19) and that blocking of LFA-1 on antigen-specific CD4+ T cells hampers tubular remodeling of LE in murine DCs (20).

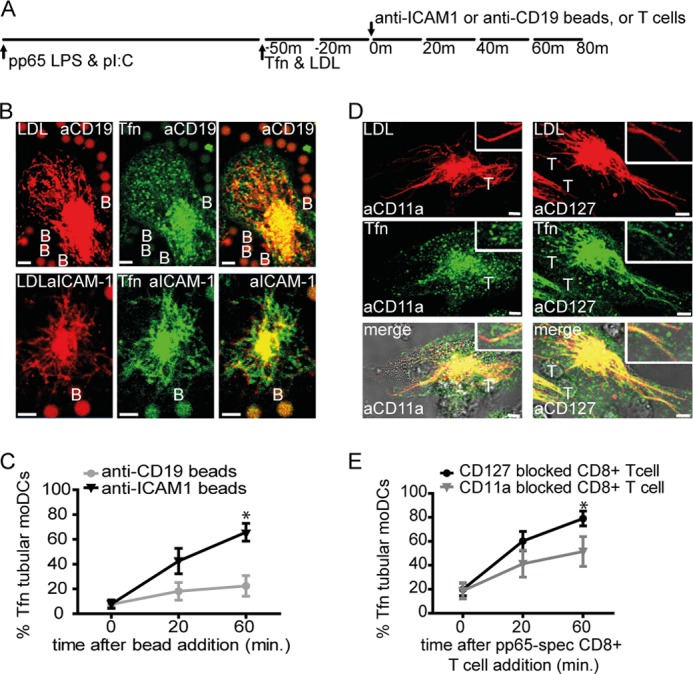

To engage ICAM-1 productively, we coated beads with stimulating antibodies (Ab) against ICAM-1 (19). As negative control we used beads coated with isotype-identical Ab specific for CD19, which is not expressed on moDCs. We performed the live cell confocal imaging experiments using Ab-coated beads similar to earlier imaging experiments (Fig. 3A). Addition of anti-ICAM-1 mAb-coated beads to these moDCs induced tubular transformation of Tfn+ juxtanuclear positioned endosomes within 30 min, reaching 60–70% of moDCs showing tubular recycling endosomes at 60 min. Addition of anti-CD19 mAb-coated beads did not induce remodeling of Tfn+ compartments (Fig. 3, B and C). Similar data were obtained using anti-CD45 beads.3

FIGURE 3.

ICAM-1 clustering provokes tubulation of Tfn+ endosomal recycling compartments in human dendritic cells. A, schematic outline of live cell confocal microscopy experiment in B and D. B, representative images of moDCs upon anti-CD19 (upper images) or anti-ICAM-1 (lower images) mAb-coated beads contact. C, percentage of LDL+ tubular moDCs expressing tubular Tfn+ endosomes after 4 h culture in the presence of 3 μg of HCMV-derived pp65-LPS-poly(I:C), prior to stimulation (t = 0) or at the indicated time points upon the addition of anti-CD19 (gray circles), anti-ICAM-1 (black triangles) mAb-coated beads (1:4 DC/bead ratio). One-tailed, Mann-Whitney U test was used. *, p < 0.05. Data represent mean ± S.E. (error bars) of four independent experiments. D, representative images of moDCs upon CD11a (LFA-1, left three images) or CD127 (IL7R, right three images) blocking pp65-specific CD8+ T cell contact. E, percentage of LDL+ tubular moDCs expressing tubular Tfn+ endosomes after 4 h culture in the presence of 3 μg of HCMV-derived pp65/LPS/poly(I:C), prior to stimulation (t = 0) or at the indicated time points upon the addition of CD11a (LFA-1, gray triangles) or CD127 (IL7R, black circles) blocking pp65-specific CD8+ T cells (1:1 DC:T cell ratio). One-tailed, Mann-Whitney U test was used. *, p < 0.05. Data represent mean ± S.E. of six independent experiments. Boxes are enlarged part of images. Red, LDL; green, Tfn; yellow, co-localization of LDL and Tfn; T, CD11a or CD127-blocked pp65-specific CD8+ T cell; B, mAb-coated bead. Scale bars, 5 μm.

To confirm whether the absence of ICAM-1-LFA-1 interaction counteracts CD8+ T cell-induced tubular remodeling of ERCs, we preincubated CD8+ T cells with anti-LFA-1 (anti-CD11a)-blocking Ab and added these to antigen-laden moDCs. CD127 (IL-7 receptor α) molecules are not involved with DC-T cell interaction and were therefore blocked on CD8+ T cells as a control. We found that CD8+ T cell pretreatment with anti-LFA-1 mAb counteracted the induction of tubular Tfn+ ERCs in interacting moDCs, whereas pretreatment with anti-CD127 did not (Fig. 3, D and E). Thus, ICAM-1-LFA-1 interaction between moDCs and interacting CD8+ T cells instigates ERC remodeling into elongated tubular structures in moDCs.

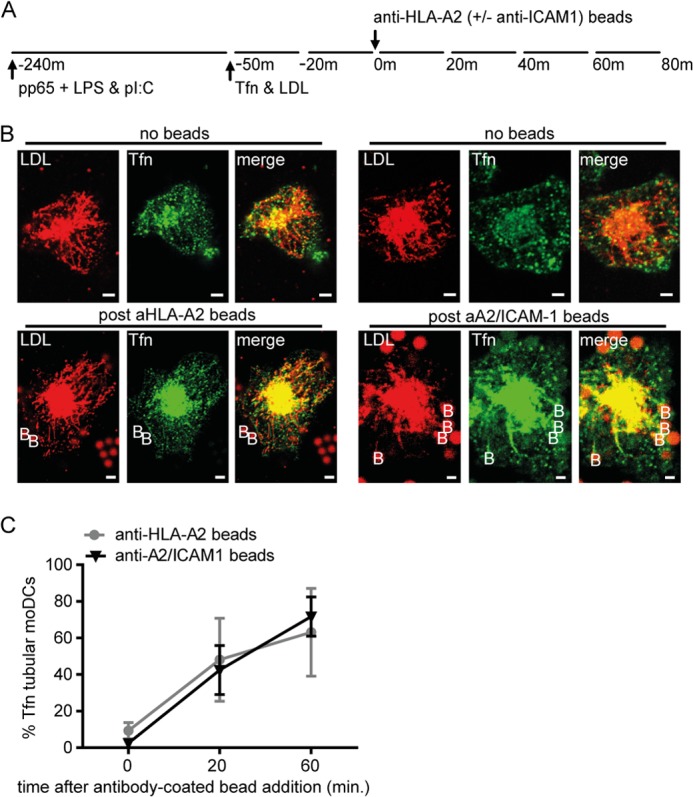

Class I MHC Clustering, or Simultaneous ICAM-1/Class I MHC Clustering, Provokes Tubulation of Tfn+ Endosomal Recycling Compartments in Human Dendritic Cells

ICAM-1-LFA-1 binding induces moderate levels of tubular transformation of Tfn+ ERC in moDCs compared with cognate DC-CD8+ T cells. During cognate DC-CD8+ T cell interaction, both peptide-Class I MHC binding to the antigen-specific TCR and binding of ICAM-1 to LFA-1 occur in parallel. We next asked whether ligation of MHC complexes, or co-ligation together with ICAM-1, is responsible for more tubular endosomal transformations in moDCs. To address this question, we exposed moDCs to anti-Class I MHC (anti-HLA-A2) mAb-coated beads or beads coated with both anti-HLA-A2 and anti-ICAM-1 (Fig. 4A). After 60 min of bead binding, up to 60–70% of LE-remodeled human DCs showed tubular recycling endosomes (Fig. 4, B and C). Thus, both anti-ICAM-1 mAb-coated and double-coated (anti-A2/anti-ICAM-1 mAb) beads efficiently induced tubular remodeling of Tfn+ ERC. In conclusion, sufficient cross-linking of HLA-A2 and/or ICAM-1 molecules on the DC surface by mAb-coated beads or antigen-specific T cells drives Tfn+ endosomal tubular remodeling.

FIGURE 4.

Class I MHC clustering or simultaneous ICAM-1-Class I MHC clustering, provokes tubulation of Tfn+ endosomal recycling compartments in human dendritic cells. A, schematic outline of live cell confocal microscopy experiment in B. B, representative images of moDCs upon anti-HLA-A2 mAb (left six images) or anti-ICAM-1/anti-HLA-A2 (right six images). Red, LDL; green, Tfn; yellow, co-localization of LDL and Tfn; B, mAb-coated beads. Scale bars, 5 μm. C, percentage of LDL+ tubular moDCs expressing tubular Tfn+ endosomes after 4-h culture in the presence of 3 μg of HCMV-derived pp65-LPS-poly(I:C) prior to stimulation (t = 0) or at the indicated time points upon the addition of anti-ICAM-1/anti-HLA-A2 (black triangles) or anti-HLA-A2 mAb (gray circles)-coated beads (1:4 DC:bead ratio). One-tailed, Mann-Whitney U test was used. *, p < 0.05. Data represent mean ± S.E. (error bars) of three independent experiments.

Elongated Recycling Endosomal Tubules Require an Intact Microtubule Cytoskeleton and Unperturbed Endosomal Recycling in Human Dendritic Cells

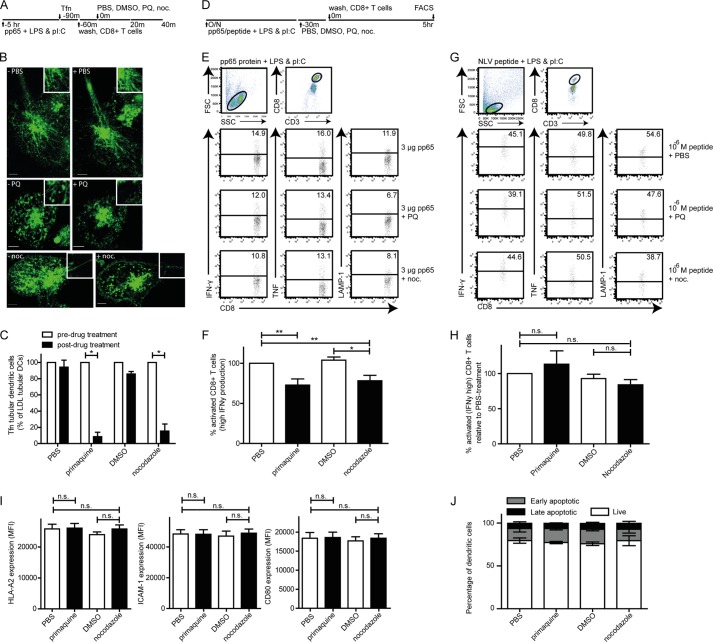

In murine DCs, tubulation of LE compartments requires the support of an intact microtubule-driven cytoskeleton (7). The cellular requirements for ERC remodeling are unknown. Therefore, we tested whether recycling from the endosomal pathway to the DC surface is necessary and whether an intact microtubule cytoskeleton is required. We made use of the reversible inhibitors primaquine (50 μm) or nocodazole (10 μm) (Fig. 5, A–C) (11, 15). We used these inhibitors as published in DCs (21, 22). We induced tubulation of Tfn+ ERCs by a 1-h culture of antigen-LPS-poly(I:C)-stimulated moDCs with antigen-specific CD8+ T cells (Fig. 5, A, schematic outline of the experiment, and B, confocal image). Thirty min of primaquine or nocodazole treatment resulted in a significant reduction in moDCs with tubular Tfn+ endosomes to 8 and 17%, respectively (Fig. 5, B and C). Thus, tubular Tfn+ recycling endosomes require intact microtubules and continuous endosomal recycling.

FIGURE 5.

Disintegration of tubular Tfn+ endosomal recycling compartments in human dendritic cells associates with reduced ability of dendritic cells to activate antigen-specific CD8+ T cells. A, schematic outline of live cell confocal microscopy experiment in B and C. B and C, representative images (B) and the percentage (C) of selected 3-μg HCMV-derived pp65-LPS-poly(I:C)-laden moDCs after 1 h of co-culture with pp65-specific CD8+ T cells and pretreatment (left three images in B, white bars in C) or after 30 min of the indicated drug treatment (right three images in B, black bars in C). PQ, primaquine, 50 μm; noc, nocodazole, 10 μm; green, Tfn. Scale bar, 5 μm. Data represent the mean ± S.E. (error bars) of at least four independent experiments. D, schematic outline of experimental setup for E–H. E, human moDCs were loaded (overnight, 37 °C) with 0 or 3 μg of HCMV-derived pp65 in the presence of 200 ng/ml LPS and 5 μg/ml poly(I:C). MoDCs were treated (30 min, 37 °C) with either 50 μm primaquine biphosphate, 1 μg/ml nocodazole, or carrier controls PBS, and DMSO, followed by extensive washing (three washes). Next, pp65-specific CD8+ T cells were added for co-culture with the treated moDCs (1:1, 5 h, 37 °C). DC-mediated activation of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells was measured by analysis of induced production of IFNγ, TNF, or surface-expressed LAMP-1 high (bar in dot plot is background, based on 1% cytokine-positive CD8+ T cells upon culture with LPS and poly(I:C)-treated moDCs in absence of antigen). F, percentage of antigen-specific activated CD8+ T cells, determined relative to matched PBS treated-moDCs. G, human moDCs were loaded (overnight, 37 °C) with pp65-derived NLV-peptide in the presence of 200 ng/ml LPS and 5 μg/ml poly(I:C). MoDCs were treated (30 min, 37 °C) with either 50 μm primaquine biphosphate, 1 μg/ml nocodazole, or carrier controls PBS, and DMSO, followed by extensive washing (three washes). Next, pp65-specific CD8+ T cells were added for co-culture with the treated moDCs (1:1, 5 h, 37 °C) and antigen-specific CD8+ T cell activation was determined. H, percentage of antigen-specific activated CD8+ T cells, determined relative to matched PBS-treated moDCs. Human moDCs were loaded (overnight, 37 °C) with 3 μg of HCMV-derived pp65 in the presence of 200 ng/ml LPS and 5 μg/ml poly(I:C). MoDCs were treated (30 min, 37 °C) with either 50 μm primaquine biphosphate, 1 μg/ml nocodazole, or carrier controls PBS, and DMSO, followed by extensive washing (three washes). Thereafter, HLA-A2, ICAM-1, and CD80 expression on (I) or viability (J) of moDCs was determined by flow cytometry analysis. Data represent mean ± S.E. (error bars) of at least three independent experiments. Two-tailed, Mann-Whitney U test was used. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01.

Abolishment of Tubular ERC Compartments in Human Dendritic Cells Is Associated with Reduced Ability to Activate CD8+ T Cells

Does tubular transformation of ERCs have a functional consequence in antigen presentation by DCs? Molecules that selectively support tubular endosomes have not yet been described, precluding a knockdown-based approach. We therefore used pharmacological reagents primaquine and nocodazole to address this question, as in Fig. 5, A–C. We recently established a human DC-based cross-presentation model (15), which we adapted to compare antigen-specific CD8+ T cell activation by moDCs that are either able or temporarily unable to express tubular ERCs, by 30-min treatment of DCs with primaquine (50 μm) or nocodazole (10 μm) just prior to administration of T cells (schematically depicted in Fig. 5D). Using this approach, adverse effects of the drugs on moDC-mediated antigen uptake or processing, as well as direct effects on CD8+ T cells, were prevented (11, 15). Antigen-specific CD8+ T cells were next added to untreated or primaquine- or nocodazole-treated moDCs (5-h culture, 37 °C). Both reversible primaquine and nocodazole 30-min treatment significantly reduced antigen-specific CD8+ T cell activation, as measured by decreased IFNγ production (Fig. 5F, 27 and 22% reduction, respectively). Concomitantly, TNF production and surface-expressed LAMP-1 on CD8+ T cells were reduced as well (Fig. 5, E and F). Both reversible primaquine and nocodazole 30-min treatment did not significantly affect presentation of pre-processed pp65-derived NLVPMVATV-peptide (Fig. 5, G and H), DC surface expression of HLA-A2, ICAM-1, and CD80 (Fig. 5I), and DC viability (Fig. 5J). Because both inhibitors were added after antigen uptake and overnight antigen processing, possible effects on antigen uptake and processing were excluded. Taken together, this shows that primaquine and nocodazole affect endosomal tubulation, but does not interfere with other processes that are pivotal to antigen-dependent CD8+ T cell activation. Abolishment of the tubular structure of ERC in human DCs associates with reduced ability of DCs to activate antigen-specific CD8+ T cells.

DISCUSSION

Various environmental cues, including TLR ligands, induce DC maturation. During maturation the DCs rapidly transform from endocytic cells that survey their immediate surroundings, into cells dedicated to antigen presentation. As the processing of antigen and assembly of peptide-loaded MHC complexes occurs at intracellular locations, transport of peptide-MHC complexes to the DC surface is critical for display to T cells. Here we show that TLR triggering-induced maturation rapidly drives vesicle-to-tubule transformation of late endosomal compartments in human DCs. This corroborates earlier studies performed on murine DCs (8, 10). TLR signaling does not suffice to drive Tfn+ recycling endosomal tubulation, which suggests that induction of endosomal tubulation does not necessarily direct DCs toward maturation. However, as antigen-specific CD8+ T cells only induced tubulation of recycling endosomes in the presence of LPS and poly(I:C), we believe that DC maturation is a prerequisite for endosomal tubulation. Whether there is selection of endosomal tubulation in response to distinct TLR stimuli, as was proposed for phagosome maturation, is yet unknown (23).

It is reported that in the absence of TLR stimuli, T cells cannot stimulate late endosomal tubulation in both human and mice (8). In contrast to murine DCs, the addition of T cells in the presence of TLR ligand does not further stimulate late endosomal tubulation. Whether this is due to usage of human CD8+ T cells instead murine CD4+ T cells is not known.

We confirmed the necessity of ICAM-1-LFA-1 and HLA-A2-TCR interactions in remodeling of early/recycling endosomal compartments in DCs that bind T cells, by use of antibody-coated beads as surrogate T cells as well as with blocking experiments. Of note, in our bead experiments, we found equal efficiency at inducing tubular remodeling of Tfn+ endosomal compartments using HLA-A2 mAb-, ICAM-1 mAb-, or double mAb-coated beads (Figs. 3C, and 4, B and C). Whether this finding is relevant to DCs that interact with T cells or only true to those that interact with mAb-coated beads, we could not fully address. However, because DC-T cell contact induces the rearrangement of HLA-A2 and ICAM-1 into immune synapse-like structures on the DC surface (24), we consider it unlikely that singular HLA-A2 clustering drives ERC tubular remodeling. In our bead assays, supraphysiological cross-linking of either HLA-A2 or ICAM-1 molecules may already facilitate immune synapse-like structures. Indeed, in live cells, HLA-A2 and ICAM-1 have increased association with each other upon cross-linking of either ICAM-1 or HLA-A2 (19).

We are not the first to relate Tfn+ compartments in DCs to Class I MHC-mediated stimulation of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells. It had been known that peptide-receptive Class I MHC molecules are present in endosomes (25). Moreover, Class I MHC molecules are present in primaquine-sensitive or Tfn+ compartments (26, 27). In murine DCs, soluble antigen-derived peptide loading onto Class I MHC molecules occurs within Tfn+ endosomes in an LPS-dependent manner (5). Murine DCs that lack Class I MHC molecules in recycling endosomes due to an aberrant tyrosine-based internalization motif, were shown to be defective in cross-presentation (28). Finally, tubular recycling endosomes can mediate efficient Class I MHC recycling in HeLa cells, and HLA-A and ICAM-1 signaling is essential in viral antigen presentation to CD8+ T cells (14, 19). Altogether, data by us and others provide experimental support that in human DCs tubular transformation of Tfn+ ERCs modulates the recycling peptide-Class I MHC complexes and their display to antigen-specific CD8+ T cells.

Recently, it was shown that infection of HeLa or RAW cells by S. typhimurium promote LE tubulation in these cells to increase cell-to-cell transfer of Salmonella (13). These data show that endosomal tubular transformation is not restricted to DCs. In addition, it raises the possibility that pathogens may exploit interference of endosomal tubulation to inhibit surface-directed transport of peptide-MHC complexes. Discovery of pathogen-derived molecules that selectively inhibit endosomal tubulation would be beneficial to determine molecular mechanisms involved in endosomal remodeling.

The stimulation and clonal expansion of CD8+ T cells by antigen presenting DCs require the sequential interaction of an estimated 200 TCR molecules with antigen-specific peptide-Class I MHC complexes (29). As DC maturation does not drastically increase surface expression of Class I MHC molecules (30–32) selective recruitment of specific peptide-MHC complexes toward the DC-T cell contact zone must occur. We believe such recruitment is supported by endosomal tubules that polarize toward the cell surface. We show that the induced transformation of tubular ERC structures occurs efficient only when (i) sufficient clustering of HLA-A2 and/or ICAM-1 occurs at the DC surface and (ii) TLR stimulation is provided. The requirement for innate stimulation through, for example, TLRs restricts remodeling to “dangerous” antigens and not endogenous self-peptides. The requirement of TLR triggering prior to CD8+ T cell activation also ensures that DCs are optimally primed for antigen presentation. Our findings collectively support a two-signal model in which the DC through tubular endosome transformation facilitates selective clonal CD8+ T cell expansion. Only antigen-specific CD8+ T cells induce sufficient ICAM-1 and HLA-A2 clustering that allow for the tubular transformation of Tfn+ ERC in DCs. Accordingly, only a sufficiently high qualitative signal, triggering of the high affinity TCR, would rally the quantitative response (peptide-MHC I complexes) that is required for full CD8+ T cell activation.

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Laboratory Translational Immunology, especially the Boes laboratory members, for their expertise and Wim Burmeister for providing the EB2 plasmid.

This work was supported by the Wilhelmina Research Fund (to M. B.).

This article contains supplemental Movies 1 and 2.

E. B. Compeer, T. W. H. Flinsenberg, and M. Boes, unpublished data.

- ERC

- endosomal recycling compartment

- DC

- dendritic cell

- DMSO

- dimethyl sulfoxide

- ICAM-1

- intercellular adhesion molecule-1

- LE

- late endosome

- LFA-1

- lymphocyte function-associated antigen 1

- moDC

- monocyte-derived dendritic cell

- poly(I:C)

- polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid

- TCR

- T cell receptor

- Tfn

- transferrin

- TLR

- Toll-like receptor

- HCMV

- human cytomegalovirus

- DiI

- 1,1′-dioctadecyl-3,3,3′,3′-tetramethylindocarbocyanine perchlorate.

REFERENCES

- 1. Grant B. D., Donaldson J. G. (2009) Pathways and mechanisms of endocytic recycling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10, 597–608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sönnichsen B., De Renzis S., Nielsen E., Rietdorf J., Zerial M. (2000) Distinct membrane domains on endosomes in the recycling pathway visualized by multicolor imaging of Rab4, Rab5, and Rab11. J. Cell Biol. 149, 901–914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Compeer E. B., Flinsenberg T. W., van der Grein S. G., Boes M. (2012) Antigen processing and remodeling of the endosomal pathway: requirements for antigen cross-presentation. Front. Immunol. 3, 37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Villadangos J. A., Schnorrer P. (2007) Intrinsic and cooperative antigen-presenting functions of dendritic cell subsets in vivo. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 7, 543–555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Burgdorf S., Schölz C., Kautz A., Tampé R., Kurts C. (2008) Spatial and mechanistic separation of cross-presentation and endogenous antigen presentation. Nat. Immunol. 9, 558–566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ackerman A. L., Kyritsis C., Tampé R., Cresswell P. (2005) Access of soluble antigens to the endoplasmic reticulum can explain cross-presentation by dendritic cells. Nat. Immunol. 6, 107–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Boes M., Cerny J., Massol R., Op den Brouw M., Kirchhausen T., Chen J., Ploegh H. L. (2002) T-cell engagement of dendritic cells rapidly rearranges MHC class II transport. Nature 418, 983–988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Boes M., Bertho N., Cerny J., Op den Brouw M., Kirchhausen T., Ploegh H. (2003) T cells induce extended class II MHC compartments in dendritic cells in a Toll-like receptor-dependent manner. J. Immunol. 171, 4081–4088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kleijmeer M., Ramm G., Schuurhuis D., Griffith J., Rescigno M., Ricciardi-Castagnoli P., Rudensky A. Y., Ossendorp F., Melief C. J., Stoorvogel W., Geuze H. J. (2001) Reorganization of multivesicular bodies regulates MHC class II antigen presentation by dendritic cells. J. Cell Biol. 155, 53–63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chow A., Toomre D., Garrett W., Mellman I. (2002) Dendritic cell maturation triggers retrograde MHC class II transport from lysosomes to the plasma membrane. Nature 418, 988–994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Vyas J. M., Kim Y. M., Artavanis-Tsakonas K., Love J. C., Van der Veen A. G., Ploegh H. L. (2007) Tubulation of class II MHC compartments is microtubule-dependent and involves multiple endolysosomal membrane proteins in primary dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 178, 7199–7210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Barois N., de Saint-Vis B., Lebecque S., Geuze H. J., Kleijmeer M. J. (2002) MHC class II compartments in human dendritic cells undergo profound structural changes upon activation. Traffic 3, 894–905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kaniuk N. A., Canadien V., Bagshaw R. D., Bakowski M., Braun V., Landekic M., Mitra S., Huang J., Heo W. D., Meyer T., Pelletier L., Andrews-Polymenis H., McClelland M., Pawson T., Grinstein S., Brumell J. H. (2011) Salmonella exploits Arl8B-directed kinesin activity to promote endosome tubulation and cell-to-cell transfer. Cell. Microbiol. 13, 1812–1823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Caplan S., Naslavsky N., Hartnell L. M., Lodge R., Polishchuk R. S., Donaldson J. G., Bonifacino J. S. (2002) A tubular EHD1-containing compartment involved in the recycling of major histocompatibility complex class I molecules to the plasma membrane. EMBO J. 21, 2557–2567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Flinsenberg T. W., Compeer E. B., Koning D., Klein M., Amelung F. J., van Baarle D., Boelens J. J., Boes M. (2012) Fcγ receptor antigen targeting potentiates cross-presentation by human blood and lymphoid tissue BDCA-3+ dendritic cells. Blood 120, 5163–5172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Traer C. J., Rutherford A. C., Palmer K. J., Wassmer T., Oakley J., Attar N., Carlton J. G., Kremerskothen J., Stephens D. J., Cullen P. J. (2007) SNX4 coordinates endosomal sorting of TfnR with dynein-mediated transport into the endocytic recycling compartment. Nat. Cell Biol. 9, 1370–1380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Scholer A., Hugues S., Boissonnas A., Fetler L., Amigorena S. (2008) Intercellular adhesion molecule-1-dependent stable interactions between T cells and dendritic cells determine CD8+ T cell memory. Immunity 28, 258–270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dustin M. L., Springer T. A. (1989) T-cell receptor cross-linking transiently stimulates adhesiveness through LFA-1. Nature 341, 619–624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lebedeva T., Anikeeva N., Kalams S. A., Walker B. D., Gaidarov I., Keen J. H., Sykulev Y. (2004) T-cell receptor cross-linking transiently stimulates adhesiveness through LFA-1. Immunology 113, 460–47115554924 [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bertho N., Cerny J., Kim Y. M., Fiebiger E., Ploegh H., Boes M. (2003) Requirements for T cell-polarized tubulation of class II+ compartments in dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 171, 5689–5696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. van Weert A. W., Geuze H. J., Groothuis B., Stoorvogel W. (2000) Primaquine interferes with membrane recycling from endosomes to the plasma membrane through a direct interaction with endosomes which does not involve neutralisation of endosomal pH nor osmotic swelling of endosomes. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 79, 394–399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hasegawa S., Hirashima N., Nakanishi M. (2001) Microtubule involvement in the intracellular dynamics for gene transfection mediated by cationic liposomes. Gene Ther. 8, 1669–1673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Blander J. M., Medzhitov R. (2004) Regulation of phagosome maturation by signals from toll-like receptors. Science 304, 1014–1018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dustin M. L., Tseng S. Y., Varma R., Campi G. (2006) T cell-dendritic cell immunological synapses. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 18, 512–516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Grommé M., UytdeHaag F. G., Janssen H., Calafat J., van Binnendijk R. S., Kenter M. J., Tulp A., Verwoerd D., Neefjes J. (1999) Recycling MHC class I molecules and endosomal peptide loading. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 10326–10331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Di Pucchio T., Chatterjee B., Smed-Sörensen A., Clayton S., Palazzo A., Montes M., Xue Y., Mellman I., Banchereau J., Connolly J. E. (2008) Direct proteasome-independent cross-presentation of viral antigen by plasmacytoid dendritic cells on major histocompatibility complex class I. Nat. Immunol. 9, 551–557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Reid P. A., Watts C. (1990) Cycling of cell surface MHC glycoproteins through primaquine-sensitive intracellular compartments. Nature 346, 655–657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lizée G., Basha G., Tiong J., Julien J. P., Tian M., Biron K. E., Jefferies W. A. (2003) Control of dendritic cell cross-presentation by the major histocompatibility complex class I cytoplasmic domain. Nat. Immunol. 4, 1065–1073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Christinck E. R., Luscher M. A., Barber B. H., Williams D. B. (1991) Peptide binding to class I MHC on living cells and quantitation of complexes required for CTL lysis. Nature 352, 67–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cella M., Engering A., Pinet V., Pieters J., Lanzavecchia A. (1997) Inflammatory stimuli induce accumulation of MHC class II complexes on dendritic cells. Nature 388, 782–787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ackerman A. L., Cresswell P. (2003) Regulation of MHC class I transport in human dendritic cells and the dendritic-like cell line KG-1. J. Immunol. 170, 4178–4188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Delamarre L., Holcombe H., Mellman I. (2003) Presentation of exogenous antigens on major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I and MHC class II molecules is differentially regulated during dendritic cell maturation. J. Exp. Med. 198, 111–122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]