Background: The structure of GH115 glucuronidases that remove glucuronic acid from xylan chains is unknown.

Results: Bacteroides ovatus GH115 glucuronidase is a dimeric enzyme that contains a flexible active site pocket.

Conclusion: The assembly of the catalytic apparatus of the glucuronidase requires substantial conformational changes.

Significance: Conformational changes are highly unusual in glycoside hydrolases.

Keywords: Bioenergy, Enzyme Structure, Glycoside Hydrolases, Plant Cell Wall, X-ray Crystallography

Abstract

The microbial degradation of the plant cell wall is an important biological process that is highly relevant to environmentally significant industries such as the bioenergy and biorefining sectors. A major component of the wall is glucuronoxylan, a β1,4-linked xylose polysaccharide that is decorated with α-linked glucuronic and/or methylglucuronic acid (GlcA/MeGlcA). Recently three members of a glycoside hydrolase family, GH115, were shown to hydrolyze MeGlcA side chains from the internal regions of xylan, an activity that has not previously been described. Here we show that a dominant member of the human microbiota, Bacteroides ovatus, contains a GH115 enzyme, BoAgu115A, which displays glucuronoxylan α-(4-O-methyl)-glucuronidase activity. The enzyme is significantly more active against substrates in which the xylose decorated with GlcA/MeGlcA is flanked by one or more xylose residues. The crystal structure of BoAgu115A revealed a four-domain protein in which the active site, comprising a pocket that abuts a cleft-like structure, is housed in the second domain that adopts a TIM barrel-fold. The third domain, a five-helical bundle, and the C-terminal β-sandwich domain make inter-chain contacts leading to protein dimerization. Informed by the structure of the enzyme in complex with GlcA in its open ring form, in conjunction with mutagenesis studies, the potential substrate binding and catalytically significant amino acids were identified. Based on the catalytic importance of residues located on a highly flexible loop, the enzyme is required to undergo a substantial conformational change to form a productive Michaelis complex with glucuronoxylan.

Introduction

The microbial degradation of plant biomass in soil is critical to the carbon cycle and is of increasing importance in environmentally significant industries, particularly the bioenergy and biorefining sectors, where the plant cell wall is the key substrate (1). Furthermore, dietary plant glycans that are not degraded by mammalian intestinal enzymes are the major nutrient available to the microbial communities of the fore-stomach or rumen in ruminants, and the large bowel in monogastric mammals (2). In humans the fermentation of dietary glycans by the microbes of the large bowel (defined as the microbiota) contributes up to 10% of daily calories (3). The microbiota also has a significant impact on the host through interactions with the immune system, which in turn can affect human health (see Ref. 4 for review). Plant cell walls present a highly complex substrate, and thus microorganisms that utilize these composite structures express an array of catabolic enzymes, primarily glycoside hydrolases, but also carbohydrate esterases and polysaccharide lyases, which degrade the structural polysaccharides into their component monosaccharides (see Refs. 5 and 6 for review). These enzymes are grouped into sequence-based families in the CAZy database (glycoside hydrolase and carbohydrate esterase families are defined as GH and CE, respectively) (7).

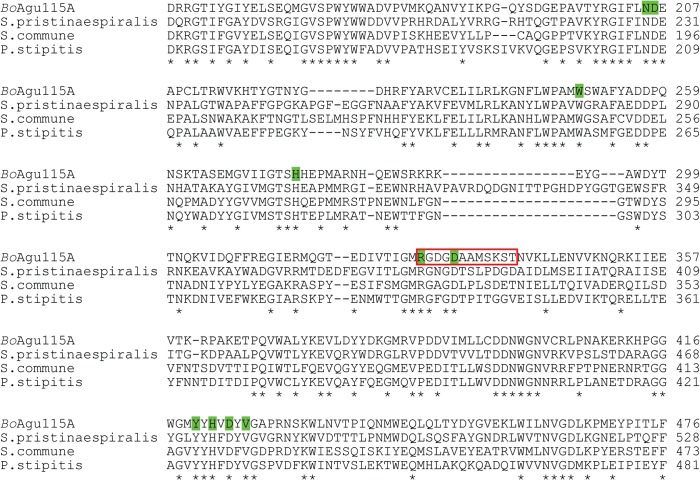

Xylan, the major matrix polysaccharide of plant cell walls, consists of β1,4-linked d-xylose residues decorated at O2 and/or O3 with l-arabinofuranose and acetyl groups, and exclusively at O2 with α-d-glucuronic acid (GlcA) or 4-O-methyl-GlcA (MeGlcA) (Fig. 1) (8). These decorated regions make the polymer backbone recalcitrant to attack by most endo-xylanases and also block the action of xylosidases. To overcome this bottleneck, the side chains are removed by specific debranching enzymes, acetyl esterases, α-l-arabinofuranosidases, and α-glucuronidases (reviewed in Refs. 5 and 6). The majority of α-glucuronidases that hydrolyze the GlcA and MeGlcA decorations are located in GH67 (9, 10). These enzymes, however, do not attack glucuronoxylan, they only remove uronic acid from the non-reducing end of glucurono-xylooligosaccharides (9, 10). The structure of several GH67 enzymes show that O4 of the xylose decorated with GlcA is pointing at the surface of the enzymes, explaining why these α-glucuronidases can only target uronic acids attached to the non-reducing end of xylan chains (10, 11). Recently, two microbial eukaryotic enzymes from GH115 were shown to be α-glucuronidases that could cleave GlcA and MeGlcA from both the non-reducing end and internal xylose units of xylan and xylo-oligosaccharides (12, 13), displaying a single displacement acid base-assisted (inverting) mechanism, which results in inversion of the anomeric configuration of the cleaved uronic acid (14). The two enzymes had a higher specific activity against glucurono-xylooligosaccharides compared with glucuronoxylan, although no kinetic parameters for these enzymes were reported. As no crystal structure for a GH115 enzyme is available, the structural basis for the specificity of these α-glucuronidases is unknown.

FIGURE 1.

Schematic of xylan. The schematic shows a basic xylan structure, the enzyme classes that hydrolyze the various linkages, and their respective major CAZy families. Simple glucuronoxylans predominate in the walls of dicots, whereas monocots usually contain more complex glucuronoarabinoxylans.

To date, GH115 contains 237 members of which the majority (177) are bacterial, although only a single prokaryotic enzyme (from Streptomyces pristinaespiralis) has been shown to display α-glucuronidase activity (15). Bacteroidetes is a major phylum in the human gut microbiota. These organisms, exemplified by Bacteroides ovatus, are capable of degrading an extensive range of human and plant glycans (16). This glycan-degrading capacity is orchestrated by physically linked and co-regulated genes that are known as polysaccharide utilization loci (see Ref. 17 for review). The genome of B. ovatus contains seven open reading frames that are annotated as GH115s, two of which are in a polysaccharide utilization locus that is up-regulated during growth on complex xylans (16). Here we report the biochemical characterization and structure of one of these enzymes, BACOVA_03449, defined henceforth as BoAgu115A. The enzyme was shown to be a glucuronoxylan-specific α-glucuronidase that displayed a strong preference for uronic acids that decorate internal xylose units. The enzyme displays the same core-fold as GH67 α-glucuronidases, however, the active site residues are not conserved in the two enzymes. Mutagenesis and structural data indicate that a significant conformational change is required to assemble the catalytic apparatus in BoAgu115A.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cloning, Expression, and Purification of GH115 Enzymes

The open reading frame encoding mature forms (and truncated derivatives of BoAgu115A) of the seven B. ovatus GH115 proteins were amplified from genomic DNA (B. ovatus ATCC 8483) by PCR using primers that introduce NheI and XhoI restriction enzyme sites. The amplified DNA was cloned into the Escherichia coli expression vector pET28a (Novagen) such that the encoded recombinant proteins contain an N-terminal His6 tag. The recombinant proteins were produced in E. coli BL21 DE3 (Novagen) cells, harboring appropriate pET-based plasmids, and cultured in LB broth containing kanamycin (50 μg/ml) at 37 °C. Cells were grown to mid-exponential phase (A600 of 0.6), at which point isopropyl β-d-thiogalactopyranoside was added to a final concentration of 1 mm, and the cultures were incubated for a further 16 h at 16 °C. The cells were harvested by centrifugation, and His6-tagged recombinant protein was purified from cell-free extracts by immobilized metal affinity chromatography (IMAC) using standard methodology (18). For crystallographic studies BoAgu115A was further purified by size exclusion chromatography using a Superdex 75 column. All proteins were purified to electrophoretic homogeneity as judged by SDS-PAGE.

Mutagenesis

Site-directed mutagenesis was conducted using the PCR-based QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) according to the manufacturer's instructions, using the plasmid encoding BoAgu115A as the template and appropriate primer pairs.

Nomenclature of Oligosaccharides

The oligosaccharides are defined as follows: for homopolymers of β1,4-linked xylose residues either the full name of the saccharide is used or the degree of polymerization is indicated as a subscript (e.g. the tetrasaccharide of xylose is denoted as xylotetraose or X4). Glucurono-xylooligosaccharides are identified by their sequence (unless otherwise stated) in which X is an undecorated xylose and U is a xylose containing an α1,2-linked [Me]GlcA (e.g. UXXX is xylotetraose in which the xylose at the non-reducing end contains an α1,2-linked [Me]GlcA).

Enzyme Assays

Substrates consisted of glucurono-xylans or glucurono-xylooligosaccharides. The glucurono-xylooligosaccharides UX and UXXX were purchased from Megazyme International (County Wicklow, Ireland), whereas UXX and XUXX were made as follows: 5 g of birch wood xylan (Sigma) was digested to completion with either CjXyn10A (19) or NpXyn11A (20) xylanases in 50 mm sodium phosphate, 12 mm citrate buffer, pH 6.5, containing 1 mg/ml of BSA (PC buffer) to completion. The glucurono-xylooligosaccharides generated by CjXyn10A, UXX, or NpXyn11A, XUXX, were purified from neutral xylooligosaccharides using Dowex chromatography (9). The structure of the products were confirmed by incubation with CjGlcA67A, which generated xylotriose from the CjXyn10A product but no undecorated xylooligosaccharide from the NpXyn11A product, whereas BoAgu115A released xylotriose and xylotetraose from glucurono-xylooligosaccharides generated by the GH10 and GH11 xylanases, respectively. The deduced structure of the two glucurono-xylooligosaccharides is entirely consistent with the glucuronoxylan binding mode of the two xylanases (21, 22). Enzyme assays, in which polysaccharides or glucurono-xylooligosaccharides were the substrates, were carried out in PC buffer at 37 °C using enzyme purified to electrophoretic homogeneity by immobilized metal ion affinity chromatography. The concentration of enzyme varied from 10 nm for the wild type glucuronidase to 10 μm for the least active variants of BoAgu115A. For kinetic assays, glucuronic acid was detected using the α-d-glucuronidase assay kit in which the uronic acid released is oxidized to glucarate with the concomitant reduction of NAD+ to NADH, which was monitored continuously at 340 nm and quantified using a molar extinction coefficient of 6220 m−1 cm−1. The molar concentration of the GlcA/MeGlcA in the glucuronoxylans was quantified by digesting 100 μg of the polysaccharides to completion with BoAgu115A. To measure the activity of the BoAgu115A mutants the xylotetraose reaction product released from XUXX was monitored by high performance anion-exchange chromatography (HPAEC) as described previously (18). The reaction was carried out in 20 mm sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.0, at a substrate concentration (1 mm) that was well below the KM. Thus, the initial rate of hydrolysis of the glucurono-xylooligosaccharides gives a direct readout of kcat/KM (19). The glucuronidase-catalyzed reactions were also subjected to Polysaccharide Analysis using Carbohydrate gel Electrophoresis (PACE)4 as follows: a alcohol-insoluble residue was prepared from mature Arabidopsis thaliana wild type and gux1gux2 stems as well as wild type willow, barley, sugar cane, and Miscanthus stems, as previously described (23). Alcohol-insoluble residue (500 μg) was pre-treated with 20 μl of 4 m NaOH for 1 h, neutralized with HCl, and ammonium acetate buffer, pH 6.0, added to a final concentration of 0.1 m and a final volume of 500 μl. The Arabidopsis alcohol-insoluble residue was digested to completion with xylanases (CjXyn10A and NpXyn11A), a glucuronoxylanase (BoGH30; Bacova_03432), and GH67 and GH115 α-glucuronidases (CjGlcA67A and BoAgu115A) as stated in the text and then dried in vacuum, whereas the other xylans were just digested with BoAgu115A. Released mono- and oligosaccharides were labeled with 8-aminonaphthalene-1,3,6-trisulfonic acid (Invitrogen) and separated by gel electrophoresis as previously described (24). Xylooligosaccharides (Xyl1–6, Megazyme Int.) were derivatized alongside each set of samples and run as standards within each gel.

Crystallization, Data Collection, Structure Solution, and Refinement

SeMet-BoAgu115A and native BoAgu115A, at 10 mg/ml, were crystallized from 19% PEG3350, 0.2 m sodium citrate, pH 5.5. For both selenomethionine and native enzyme, crystals were harvested in a solution containing the mother liquor supplemented with 15% (v/v) PEG 400 or Paratone N oil as cryoprotectant and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. Native crystals were soaked with 300 mm GlcA to obtain structures of BoAgu115A in complex with the uronic acid product.

Diffraction data were collected at the Diamond Light Source, Didcot, United Kingdom, on beamlines I04–1 (ligand, λ = 0.9163 Å) and I02 (native and selenomethionine, λ = 0.9795 Å) at a temperature of 100 K. Data were processed and integrated with iMosflm (25) and scaled using SCALA (26). For all datasets, the space groups were determined to be P212121 with two molecules in the asymmetric unit (giving a Matthews coefficient of about 2.7 Å3 Da−1 and a solvent content of about 50%). Heavy atom sites were found and initial phases were calculated using the HKL2MAP interface for the ShelxC/D/E pipeline (27). All other computing used the CCP4 suite of programs (28). Phases were extended to an initial native dataset at 2.65 Å and a starting model was built using Buccaneer (29). The model underwent recursive cycles of model building in COOT (30) and refinement in REFMAC (31). The native model was used as the search model for molecular replacement in Molrep to solve the ligand datasets (32). Solvent molecules were added using COOT and checked manually. Five percent of the observations were randomly selected for the Rfree set. The models were validated using Molprobity (33). The data statistics and refinement details are reported in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Data statistics and refinement details

| 03449 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Native | Selenomethionine | Ligand | |

| Data statisticsa | |||

| Beamline | IO2 | IO2 | IO4-1 |

| Date | 18/12/10 | 27/02/11 | 16/10/11 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.9795 | 0.9795 | 0.9173 |

| Resolution (Å) | 65.52-2.65 | 67.05-3.00 | 2.14 |

| (2.79-2.65) | (3.16-3.00) | (2.26-2.14) | |

| Space group | P212121 | P212121 | P212121 |

| Unit cell parameters | |||

| a (Å) | 75.39 | 76.13 | 72.04 |

| b (Å) | 131.68 | 132.75 | 130.29 |

| c (Å) | 199.40 | 201.14 | 190.17 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90.0,90.0,90.0 | 90.0,90.0,90.0 | 90.0,90.0,90.0 |

| Unit cell volume (Å3) | 2,093,534 | 2,032,772 | 1,784,954 |

| Solvent content (%) | 56 | 54 | 48 |

| No. of measured reflections | 219,395 | 1,240,973 | 272,938 |

| No. of independent reflections | 56,839 | 41,710 | 93,249 |

| Completeness (%) | 97.5 (94.5) | 100.0 (100.0) | 94.4 (91.5) |

| Redundancy | 3.9 (3.8) | 29.8 (29.9) | 2.9 (2.7) |

| Rmerge (%) | 12.6 (49.7) | 19.8 (57.3) | 9.6 (42.5) |

| 〈I〉/〈σ(I)〉 | 8.5 (2.4) | 20.2 (8) | 9.3 (2.5) |

| Anomalous completeness (%) | NA | 100.0 (100.0) | NA |

| Anomalous redundancy | NA | 15.5 (15.4) | NA |

| Refinement statisticsa | |||

| Rwork (%) | 20.34 | NAb | 17.40 |

| Rfreec (%) | 26.59 | NA | 21.91 |

| No. of non-H atoms | |||

| No. of protein, atoms | 12888 | NA | 12695 |

| No. of water molecules | 23 | NA | 602 |

| No. of other solvent atoms | 2 | NA | 13 |

| No. of ligand atoms | N/A | NA | 13 |

| Root mean square deviation from ideal values | |||

| Bond length (Å) | 0.09 | NA | 0.10 |

| Angle distance (Å) | 1.35 | NA | 1.62 |

| Average B factor (Å2) | |||

| Protein | 31.5 | NA | 26.9 |

| Ligand | NA | NA | 36.9 |

| Solvent water | 22.5 | NA | 24.8 |

| Solute ions (sodium) | 26.5 | NA | 37.3 |

| Ramachandran plot,d residues in allowed and most favored regions (%) | 99.63 | NA | 99.81 |

| Protein Data Bank codes | 4C90 | 4C91 | |

a Values in parentheses are for the highest resolution shell.

b N/A not applicable.

c 5% of the randomly selected reflections excluded from refinement.

d Calculated using MOLPROBITY.

Analytical Ultracentrifugation

Sedimentation velocity experiments were carried out in a Beckman Coulter (Palo Alto, CA) ProteomeLab XL-I analytical ultracentrifuge using interference optics. All analytical ultracentrifugation runs were carried out at the rotation speed of 48,000 rpm and experimental temperature of 20 °C; the velocity scans were taken 1 s apart, 600 scans in total. The sample volume was 400 μl. The rate protein sedimentation was used to calculate the Mr of the glucuronidase as described previously (34).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

BoAgu115A Is a Xylan-specific α-Glucuronidase

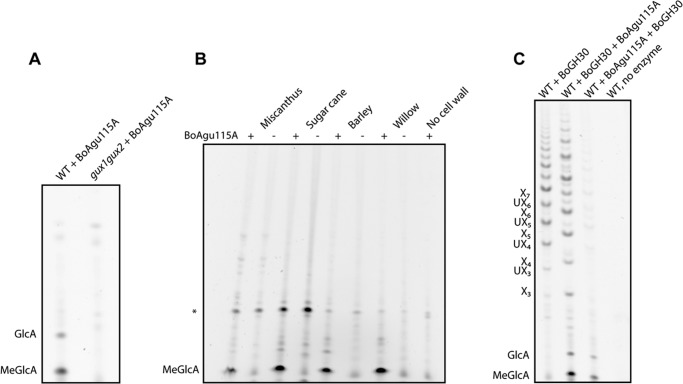

The genome of B. ovatus encodes seven proteins that are members of GH115. To explore their potential enzymatic activities, six of the seven B. ovatus GH115 proteins were expressed in E. coli in soluble form (BACOVA_00249 could not be expressed in E. coli), purified by IMAC to electrophoretic homogeneity, and their activity against glucuronoxylans was explored using PACE. The data showed that BoAgu115A released glucuronic acid (GlcA) and 4-O-methyl-GlcA (MeGlcA) from wild type Arabidopsis glucuronoxylan, but not from an Arabidopsis mutant completely lacking MeGlcA and GlcA decorations on xylan (gux1gux2) (23) (Fig. 2A). The release of both GlcA and MeGlcA demonstrate that the enzyme can accommodate the 4-O-methyl substitution of GlcA, a trait shared with the other family of α-glucuronidases, GH67. The enzyme could also remove MeGlcA from glucuronoxylans present in bioenergy-relevant dicots such as willow, and from the more complex glucuronoarabinoxylans derived from monocots such as barley, sugar cane, and Miscanthus (Fig. 2B). Thus, BoAgu115A is a α-glucuronidase that targets the uronic acids that decorate xylans. None of the other B. ovatus GH115 proteins exhibited measurable catalytic activity against a range of plant polysaccharides that contain uronic acids including glucuronoxylans, homogalacturonic acid, and rhamnogalacturonan I and II (data not shown). The lack of activity of one of these B. ovatus enzymes, BACOVA_03434, against glucuronoxylan is surprising as it is closely related to BoAgu115A (54% identity), and is encoded by a gene within the same xylan-activated polysaccharide utilization locus. In contrast, BACOVA_00492, BACOVA_00982, BACOVA_02173, and BACOVA_02777 are more distantly related to BoAgu115A and are not expressed in response to xylans, which may point to specificities that are not related to the hemicellulose.

FIGURE 2.

The release of GlcA and MeGlcA from different xylans by BoAgu115A. In panel A, wild type (WT) Arabidopsis or the mutant gux1gux2 (which does not decorate xylans with [Me]GlcA) were treated with BoAgu115A. In panel B, the xylans extracted from the four plants were subjected to PACE in the absence (−) or presence (+) of BoAgu115A. *, non-enzyme dependent product. In panel C, wild type Arabidopsis was treated with a GH30 glucuronoxylanase alone (WT + BoGH30), prior to treatment with BoAgu115A (WT + BoGH30 + BoAgu115A), or subsequent to treatment with BoAgu115A (WT + BoAgu115A + BoGH30). The glucurono-xylooligosaccharides displayed in panel C are as follows: UX3, XXUX; UX4, XXXUX; UX5, XXXXUX; UX6, XXXXXUX.

Biochemical and Biophysical Properties of BoAgu115A

To explore the catalytic properties of BoAgu115A in more detail the activity of the enzyme against glucurono-xylooligosaccharides and pre-treated glucuronoxylan was evaluated using PACE. When Arabidopsis glucuronoxylan was treated with the GH30 glucuronoxylan-specific xylanase, BACOVA_03432, a range of products were observed with the most prominent species having a degree of polymerization of 7 to 11. The GH30 enzyme was inactive against the hemicellulose that had been pre-treated with BoAgu115A (Fig. 2C), indicating that glucuronidase can remove [Me]GlcA from all locations within the hemicellulose.

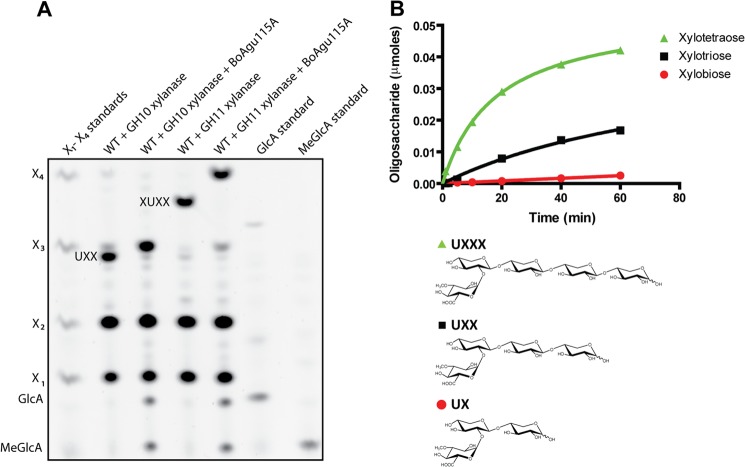

Glucurono-xylooligosaccharides were generated by digesting Arabidopsis glucuronoxylan to completion (i.e. the product profile remains stable) with GH10 or GH11 xylanases, which generated UXX and XUXX as the limit products, respectively (35). The data showed that BoAgu115A hydrolyzed UXX and XUXX (Fig. 3A), indicating that the enzyme cleaves GlcA from both non-reducing terminal and internal xylose residues, consistent with its activity against xylan, whereas the GH67 α-glucuronidase CjGlcA67A released [Me]GlcA from UXX, but not from XUXX (data not shown), consistent with its capacity to remove the uronic acid only when it decorates the non-reducing terminal xylose (9, 11).

FIGURE 3.

Activity of BoAgu115A against glucurono-xylooligosaccharides. In panel A, wild type (WT) Arabidopsis glucuronoxylan was treated with either a GH10 or GH11 xylanase that produce terminal or internally substituted glucurono-xylooligosaccharides, respectively, as their end products. The enzymes were inactivated by heating and then subjected to PACE before and after treatment with BoAgu115A. In panel B, a mixture of UX, UXX, and UXXX were incubated with BoAgu115A and the product generated over time was monitored by the release of the appropriate xylooligosaccharide by high performance anion-exchange chromatography with pulsed amperometric detection (HPAEC-PAD).

When BoAgu115A was assayed against a mixture of terminally substituted aldouronic acids the activity of the enzyme followed the order UXXX>UXX≫UX (Fig. 3B), demonstrating that the enzyme contains at least two positive subsites downstream of the +1 subsite (+2R and +3R). Positive subsites bind to the xylan backbone with the +1 subsite housing the xylose linked to the cleaved GlcA, and subsites that bind successively to sugars toward the reducing end of the xylan chain are labeled +R2, +R3 etc., whereas the subsites that bind to xylose toward the non-reducing end are defined as +NR2, +NR3 etc. (nomenclature described in Ref. 36). It was also evident that BoAgu115A was significantly more active against XUXX than UXX (Table 2), indicating that the glucuronidase contains at least one subsite upstream of the +1 subsite (+2NR). Against glucuronoxylans from birch and beech the Km of BoAgu115A is ∼10-fold lower than XUXX, whereas the kcat of the enzyme is ∼5-fold less against the polysaccharide compared with the oligosaccharide. Thus, although the α-glucuronidase has a higher catalytic efficiency against xylan than XUXX, its lower kcat likely reflects tighter binding of the deglucuronylated xylan chains (i.e. reaction product) to the positive subsites, compared with the xylooligosaccharides released from the glucurono-xylooligosaccharides, resulting in slow product release and hence turnover rate. Thus, it is possible that the xylan binding site of BoAgu115A may be able to bind more than four xylose residues.

TABLE 2.

Kinetics of wild type BoAgu115A against glucuronoxylans and glucurono-xylooligosaccharides

Data are averages and S.D. from three independent experiments.

| Substrate | kcat | Km | kcat/Km |

|---|---|---|---|

| min−1 | mm | min−1 mm−1 | |

| XUXX | 3233 (±187) | 4.5 (±0.54) | 718 |

| UXX | 1106 (±71) | 19.5 (±1.90) | 57 |

| Beech wood xylan | 696 (±38) | 0.4 (±0.06) | 1740 |

| Birch wood xylan | 665 (±24) | 0.3 (±0.04) | 2217 |

| Beech wood xylan /GH30a | 837 (±77) | 0.9 (±0.15) | 930 |

| Birch wood xylan/GH30a | 862 (±64) | 1.1 (±0.15) | 784 |

a The polysaccharide was pre-digested to completion with a GH30 glucuronoxylan-specific xylanase.

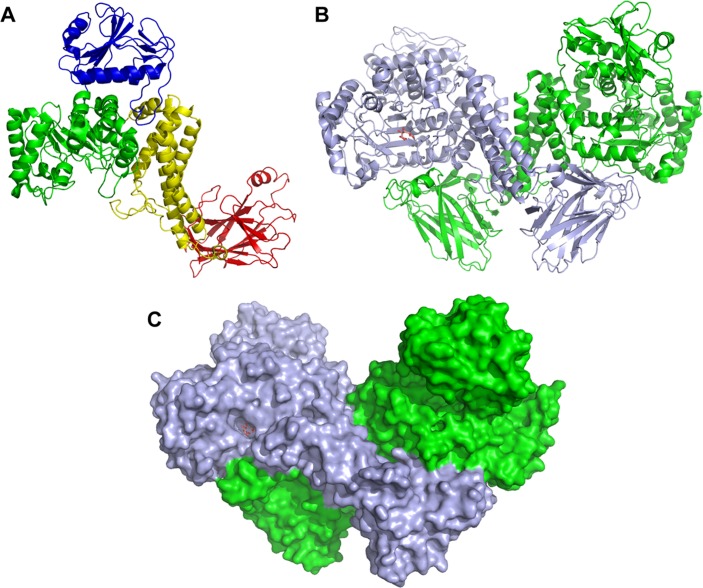

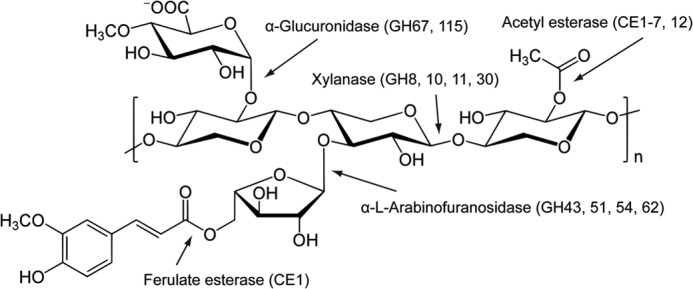

The pH optimum of BoAgu115A was ∼7.0 (Fig. 4A) and when subjected to analytical ultracentrifugation migrated with a sedimentation coefficient of 8.78 ± 0.03 S, which equates to a molecular mass of 199 ± 6.7 kDa (Fig. 4B). Given that the 824-amino acid recombinant form of BoAgu115A has a molecular mass of 85 kDa, these data indicate that the glucuronidase is a dimer in solution, consistent with its crystal structure (see below).

FIGURE 4.

BoAgu115A is a neutral acting dimeric α-glucuronidase. In panel A, the enzyme was assayed against 1 mm XUXX in 50 mm sodium acetate, sodium HEPES, and sodium phosphate buffers at the different pH values. Panel B shows the analytical ultracentrifugation of BoAgu115A.

Structure of BoAgu115A

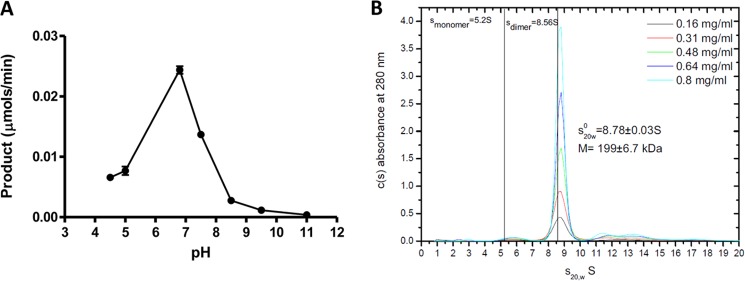

The crystal structure of the native BoAgu115A was solved by extending the phase information from an initial selenomethionine SAD at 3.0 Å to a native resolution of 2.65 Å, whereas the ligand structure of the enzyme was determined by molecular replacement at a resolution of 2.14 Å (Table 1). The final model of BoAgu115A consists of one dimeric molecule in the asymmetric unit, with each protomer consisting of residues 33–856, with an average B factor of 31.5 (Table 1). The final crystallographic R value is 20.34, with an Rfree of 26.59 for the native apo model, 17.40 and 21.91, respectively, for the ligand bound model. BoAgu115A is an α/β globular protein with overall dimensions of about 100 × 70 × 50 Å per protomer. The enzyme consists of four distinct domains, which are connected by extended loops (Fig. 5A). The N-terminal domain, residues 33–196 (all residues are identified by their position in the full-length protein), comprises six β-strands that lay on top of two parallel α-helices. The second domain (amino acids 197–482) displays a (β/α)8-fold (TIM barrel). This domain deviates slightly from a canonical TIM barrel; there is an additional helix between β-strands β-1 and β-2, and between β-3 and β-4, and the helices protruding from β-5 and β-6 are unusually short. The two α-helices of the N-terminal domain make extensive contacts with the α-helices extending from β-1 and β-2 of the TIM-barrel of the second domain. The third domain, extending from residues 488–641, comprises a five-helical bundle. The C-terminal domain, amino acids residues 673–844, displays a canonical β-sandwich-fold consisting of two β-sheets each containing five anti-parallel β-strands in the following order: β-sheet 1 (concave surface), β-1, β-8, β-3, and β-6; β-sheet 2 (convex surface), β-2, β-7, β-4, and β-5. In general the β-strands are connected by loops, however, the loop connecting β-1 and β-2 contains a pair of anti-parallel β-strands, whereas there is a short α-helix in the loop connecting β-5 with β-6. The two protomers in BoAgu115A display a “butterfly” like structure in which the two subunits make several interactions through the helical bundle domains. In addition, the C-terminal β-sandwich domain of protomer-1 makes extensive interactions with the TIM-barrel domain of protomer-2 and vice versa (Fig. 5, B and C).

FIGURE 5.

Structure of BoAgu115A. Panel A is a schematic of a protomer of BoAgu115A showing the four distinct domains of the enzyme: the N-terminal β-strand/α-helix domain (blue), the core TIM barrel catalytic domain (green), the five-helical bundle domain (yellow), and the C-terminal β-sandwich domain (red). Panel B depicts the enzyme in its dimeric butterfly-like form with protomers 1 and 2 colored green and light blue, respectively. Panel C shows a surface representation of the GH115 dimer. The relative orientation of the dimer and color of the protomers is as indicated in B. Both panels B and C show the GlcA bound form (sugar shown in stick format, carbons colored salmon pink).

Identifying the Active Site of BoAgu115A

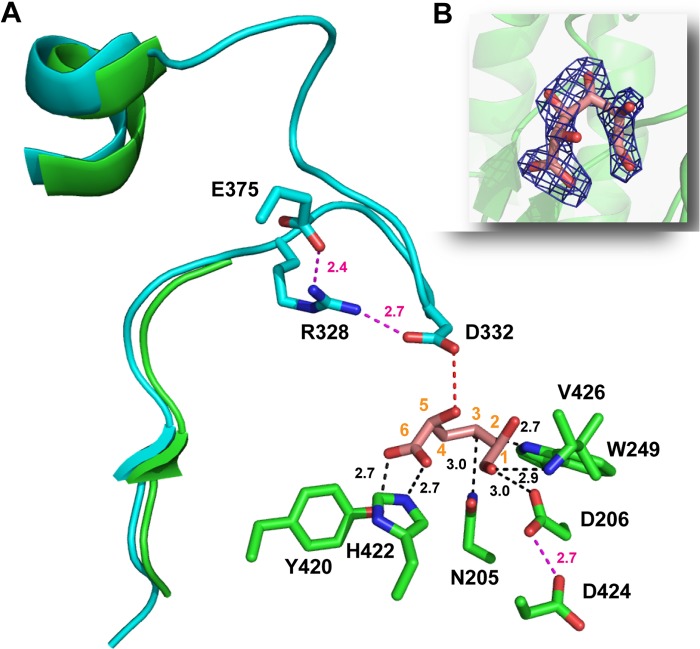

Inspection of the surface of the BoAgu115A protomers revealed a cleft-like structure in the (β/α)8 domain that extends over the central β-barrel, on the opposite surface to the N-terminal domain. The center of the cleft, which may accommodate the xylan backbone, abuts onto a deep pocket that likely comprises the active site. This hypothesis was confirmed when BoAgu115A was co-crystallized with GlcA, which revealed electron density for the uronic acid in the proposed active site pocket (Figs. 5, B and C, 6, and 7). The sugar was found to be in its ring open conformation, which is highly unusual for hexaose aldehyde sugars. It is possible that the specific interactions between the uronic acid and the enzyme encourage GlcA to adopt an open chain conformation after glycosidic bond cleavage. The direct interactions between GlcA and the enzyme are as follows (Fig. 6): O3 makes a polar contact with Nϵ-1 of Trp-249. O6A and O6B of the uronic acid carboxylate form polar contacts with the OH of Tyr-420 and Nϵ-2 of His-422, respectively, the endocyclic oxygen interacts with the N of Val-426, and O1 makes a hydrogen bond with Asp-206. O4 is pointing into a hydrophobic open channel, comprising the side chains of Phe-203, Met-248, and Trp-245, which likely make apolar contacts with the methyl group of MeGlcA. Unlike the vast majority of glycoside hydrolases, the active site of BoAgu115A does not make typical parallel stacking interactions between the planar faces of aromatic residues and the sugar ring, although edge on edge apolar interactions between the sugar and two aromatic residues, Trp-249 and Tyr-420, and the aliphatic side chain of Val-426 were evident. The Oδ-2 of Asp-332 in the apo structure (the amino acid is not visible in the structure of the BoAgu115A-GlcA complex, discussed in detail below), is in an appropriate position to make polar contacts with O2 of GlcA, whereas Oδ-1 of Asp-206 forms a polar contact with O1 and may therefore act as the catalytic acid (Fig. 6).

FIGURE 6.

The active site of BoAgu115A. Panel A shows the three-dimensional position of the amino acids (carbons colored green in the structure of the BoAgu115A-GlcA complex and cyan in the apo structure) of BoAgu115A that make polar interactions (indicated by black dotted lines) with bound GlcA (shown in stick format with carbons numbered and colored salmon pink) in its open ring conformation, or polar side contacts with other amino acids (indicated by magenta dotted lines). The distance in Å of these interactions are indicated. The red dotted line is a potential polar contact between Asp-332 and GlcA. The three-dimensional position of Arg-328, Asp-332, and Glu-375 are derived only from the apo structure of BoAgu115A as the loop containing the aspartate and arginine and the side chain of the glutamate are disordered in the BoAgu115-GlcA complex. The secondary structural elements shown in green and cyan, correspond to residues Glu-320 to Glu-345 of BoAgu115A-GlcA and apo BoAgu115A, respectively. The selected amino acids are shown in stick format with the carbons colored green (BoAgu115A-GlcA) or cyan (apo BoAgu115A) with all oxygens and nitrogens colored red and blue, respectively. Panel B shows the electron density map (2Fo − Fc) of GlcA at 1.3 σ. The electron density is shown in dark blue, protomer 1 is displays as a schematic in green and the atoms are colored as described in panel A.

FIGURE 7.

The topology of the xylan binding cleft of BoAgu115A. A and B show a solvent-exposed surface representation of the substrate binding cleft of protomer 1 of the apo (A) and GlcA bound (B) forms of BoAgu115A. In both panels the left-hand structures show a side on view down the putative xylan binding cleft (indicated with an arrow), and the right-hand structures provide a bird's eye view of the xylan binding cleft. In A and B, protomer 1 is colored light blue, protomer 2 is green, and the proximal wall (Trp-249) of the active site pocket is colored red. The flexible loop extending from Met-327 to Asn-346 is shown in cyan in B but not in A (the loop was too disordered to be modeled in the BoAgu115A-GlcA complex). C shows the position of the amino acids that interact (Lys-374, Glu-375) with residues in the flexible loop (Asp-328, Asp-332) in stick format with the carbons (and schematic of the overall fold) colored cyan (apo BoAgu115A) or green (BoAgu115A-GlcA complex), the carbons of GlcA are colored salmon pink, and all oxygens and nitrogens colored red and blue, respectively. Note the side chains of Lys-374, Glu-375, and Glu-782 are too disordered in the apo structure to be modeled. The polar contacts between the amino acids are shown by dotted lines and the distance in Å of these interactions are indicated.

To explore further the significance of the interactions between GlcA and BoAgu115A, and the function of other residues in the active site of the enzyme, targeted amino acids were substituted with alanine and the activity of the enzyme variants determined. The data, presented in Table 3 and Fig. 6, showed that mutating the residues that interact with the carboxylate of GlcA, His-422 and Tyr-420, resulted in a ∼105- and ∼103-fold reduction in activity, respectively, indicating that this component of the substrate is an important specificity determinant. O3 appears to interact with Trp-249 as the W249A mutation caused a ∼3000-fold reduction in catalytic activity. In addition to the residues that interact directly with the bound GlcA, several other amino acids in, or within the vicinity of, the active site were shown to make a significant contribution to the activity of the enzyme; the putative function of these residues is discussed below. Substituting amino acids near the putative xylan binding cleft/active site generally caused a modest reduction (5–100-fold) in the activity of the glucuronidase (see below), and mutating acid residues located in the other pocket/cleft-like structure on the enzyme (E162A, W169A, D192A, and D478A) did not affect activity (Table 3). These data are consistent with the view that the pocket located in the cleft-like structure in the TIM-barrel domain comprises the active site of BoAgu115A.

TABLE 3.

Activity of mutants of BoAgu115A

| BoAgu115A derivative | Catalytic activitya |

|---|---|

| kcat/Km min−1 m>m−1 | |

| Wild type | 780.0 |

| E162A | ∼780.0b |

| D192A | ∼780.0b |

| W169A | ∼780.0b |

| D478A | ∼780.0b |

| E785A | 198.0 |

| Y788A | 152.0 |

| E782A | 123.0 |

| N205A | 44.0 |

| Y425A | 10.8 |

| K374A | 8.0 |

| Y792A | 7.6 |

| D396N | 5.4 |

| N398A | 3.7 |

| D206A | 2.5 |

| N462A | 1.8 |

| Y373A | 1.1 |

| Y420A | 0.8 |

| H275A | 0.3 |

| W249A | 0.28 |

| E375A | 0.17 |

| H422A | 0.01 |

| R328A | 0.01 |

| H275A/H422A | NDc |

| D332A | ND |

| ΔC-terminal (1–526) | ND |

| ΔC-terminal (1–639) | ND |

| ΔC-terminal (1–665) | ND |

a Wild type and mutants of BoAgu115A were assayed using 1 mm XUXX as the substrate in 20 mm sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.0, containing 1 mg ml−1 of BSA. At this substrate concentration the initial rate provides a direct readout of the catalytic efficiency of the enzyme.

b ∼780; the activity of the mutants of residues from the other cleft/pocket-like structure on the enzyme was estimated from a single time point reaction.

c ND, no activity could be determined using an assay that can detect activity that is ∼105-fold less than the wild type enzyme.

The Possible Assembly of the Catalytic Apparatus of BoAgu115A

GH115 enzymes are inverting glycoside hydrolase (14) and thus glycosidic bond cleavage is catalyzed by an acid base-assisted single displacement mechanism. In such a mechanism the catalytic Brønsted base, typically a carboxylate, activates a water molecule that attacks the anomeric carbon of the glycone sugar, whereas the catalytic acid, also a carboxylic acid residue, donates a proton to the glycosidic oxygen promoting leaving group departure (14). As stated above, Asp-206, based on its interaction with O1 of GlcA, may comprise the catalytic acid. Support for this view is provided by the apolar environment of the aspartate; the carboxylate amino acid is in close proximity with Trp-249 and Val-426, promoting an elevated pKa. Furthermore, Oδ-2 of Asp-206 is within hydrogen bonding distance with Oδ-1 of Asp-424, and thus may function as the pKa modulator of the putative catalytic acid (Fig. 6). It should be emphasized, however, that the assignment of Asp-206 as the catalytic residue must be viewed with some caution as the D206A substitution resulted in only a 300-fold reduction in activity, and, as the bound GlcA is in an open chain form, the position of O1 may not reflect the location of the atom when the uronic acid is in a closed pyranose configuration, adopted in the substrate.

Based on mutagenesis data the other carboxylate amino acids in the vicinity of the active site, Asp-332 and Glu-375, are candidate catalytic residues; the D332A and E375A mutations caused complete inactivation of the enzyme and a ∼5000-fold reduction in activity, respectively (Table 3). It is evident, however, that the distance between Asp-332 and Glu-375 (in the apo structure) and the O1 of GlcA (in the structure of BoAgu115A in complex with GlcA); 5.4 Å and 11.8 Å, respectively, are greater than the normal ∼3.5 Å between the catalytic base and the anomeric carbon of the glycone sugar in inverting glycoside hydrolases (Fig. 6). It is possible that BoAgu115A displays a “Grotthus”-style mechanism in which a remote amino acid activates the active site nucleophilic water via a string of solvent molecules (37), as proposed for some inverting glycoside hydrolases (37, 38). In such a mechanism the distance between the catalytic base and the sugar is not restricted to 3.5 Å. Both Asp-332 and Glu-375, however, are on highly mobile loops that have high B-factors. Indeed, in the BoAgu115A-GlcA structure the loop that contains Asp-332 (Met-327 to Asn-346) was too disordered to be modeled, whereas Glu-375 could not be built past the β-carbon (Fig. 6). Thus, as discussed below, in the Michaelis catalytic complex Glu-375 and Asp-332 may adopt conformations, not observed in the apo and product structures, which reveal their true function in substrate binding and catalysis.

In enzymes and non-catalytic binding proteins that interact with glucuronic acid, arginines are often important specificity determinates, making bidentate hydrogen bonds/salt bridges with the carboxylate group (9, 39). It is possible that in BoAgu115A Arg-328 contributes to substrate binding by also interacting with the carboxylate of the glucuronic acid substrate, a view supported by the observation that the R328A mutation caused ∼105-fold decrease in activity (Table 3). Arg-328 (and Glu-375) in the apo structure, however, are too distant from the hub of the active site to play a direct role in enzyme function (Fig. 6). Thus, for the arginine to contribute to substrate binding the loop containing this amino acid (and Asp-332) would be required to undergo a conformational change. Another possibility is that the role of Arg-328 is to stabilize the conformation of Asp-332, which may function as the catalytic base, whereas the primary role of Glu-375 could be to orientate the guanidino group of the arginine toward the aspartate. To conclude, the above structural and mutagenesis data indicate that the assembly of the Michaelis complex in BoAgu115A requires the repositioning of several flexible elements, most notably the loop carrying Arg-328 and Asp-332. Indeed, close inspection of the apo structure reveals that the conformation of this loop, which forms a component of the xylan binding cleft, in addition to part of the active site pocket, likely plays a central role in both glucuronoxylan binding and departure of the reaction products, both GlcA and the undecorated xylose polymer (Fig. 7, A and B). Furthermore, the loop also plays a role in stabilizing residues in the putative xylan binding cleft, notably Lys-374 and Glu-782, whose side chains are disordered in the GlcA bound structure where the loop is too flexible to be modeled (Fig. 7C). Although conformational changes are unusual in glycoside hydrolases, they are not without precedent, exemplified by the substantial movement of the catalytic TIM-barrel domain induced by substrate binding observed in GH112 glycoside phosphorylases (40).

Whether Asp-332, or possibly Glu-375, comprise the actual catalytic base is currently unclear, as is the role of Arg-328 in substrate binding, as a Michaelis complex could not be obtained. Although the catalytic apparatus of glycoside hydrolases generally comprise two carboxylate residues, exceptions are evident with histidine acting as a catalytic acid-base in a GH3 N-acetylglucosaminidase (41), and as a catalytic acid in an inverting GH117 anhydro-l-galactosidase (42). Given that alanine substitution of His-422 caused a ∼105-fold reduction in activity, it is also possible that this residue is a component of the catalytic apparatus.

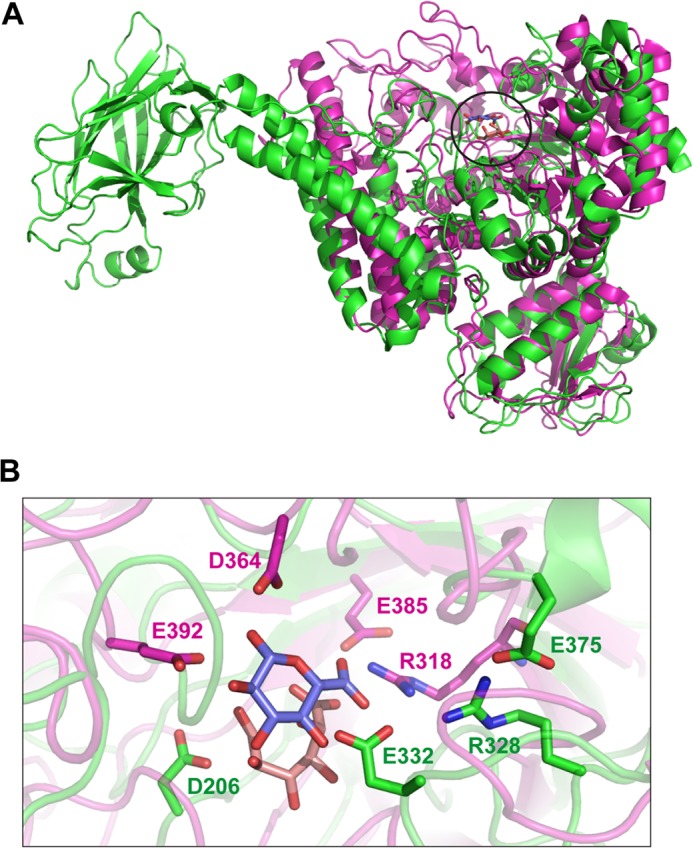

Sequence alignments showed that the residues that had the greatest influence on BoAgu115A activity (mutants of amino acids that cause >104-fold reduction in activity, those that interact with GlcA, and the proposed catalytic acid and pKa modulator, Asp-206 and Asp-424, respectively), are invariant in the other three GH115 enzymes that were shown to display α-glucuronidase activity (12, 13, 15) (Fig. 8). These data are entirely consistent with the proposed location of the BoAgu115A active site, and the likely identity of the amino acids that contribute to catalysis.

FIGURE 8.

Alignment of GH115 α-glucuronidases active against glucuronoxylan. Only the amino acids that comprise the end of the N-terminal domain and the catalytic TIM-barrel domain of the BoAgu115A are shown. Numbering in each protein is from the full-length native sequence. Identical residues in all sequences are indicated by an asterisk. Amino acids in BoAgu115A highlighted in green are implicated in the catalytic activity of the enzyme. The flexible loop in BoAgu115A that contains the key catalytic residues, Arg-328 and Asp-332, and is ordered only in the apo structure, is shown boxed in red. GenBank accession codes for the other characterized xylan-active GH115s shown are as follows: Streptomyces pristinaespiralis, EDY63299.2; Schizophyllum commune, ADV52250.1; and Pichia stipitis, ABN67901.2.

The Potential Role of the C-terminal Domain of BoAgu115A

Inspection of the dimeric form of BoAgu115A suggests that the C-terminal β-sandwich domain of protomer 2 contributes to one of the faces of the likely xylan binding cleft of protomer 1 and vice versa (Fig. 7). To explore the role of the C-terminal domain in the activity of the enzyme, alanine substitutions were made of Glu-782, Glu-785, Tyr-788, and Tyr-792, whose side chains line the proposed xylan binding cleft. The 100-fold reduction in catalytic activity mediated by the Y792A substitution (Table 3) indicated that Tyr-792 makes a significant contribution to xylan binding, whereas removal of the C-terminal domain (enzyme truncated at residue Ile-665) resulted in the complete abrogation of enzyme activity (Table 3), supporting a key role for this structural element in the topology of the GH115 catalytic apparatus.

Structural Comparison of GH115 and GH67 α-Glucuronidases

Structural comparison of BoAgu115A with the PDB database (using DaliLite version 3) identified the Geobacillus stearothermophilus GH67 α-glucuronidase, AguA (11), as the closest, albeit weak, structural homolog with a Z-score of 16.1, root mean square deviation of 4.7 Å, and sequence identity of 11% over 470 aligned resides. Despite the weak structural homology and sequence similarity, the first three domains of the two proteins display the same fold and, intriguingly, the location of the active site of the GH115 and GH67 enzymes, endo- and exo-acting xylan-specific α-glucuronidase, respectively, is conserved, pointing to a distant evolutionary link between the two families (Fig. 9A). It is evident, however, that there is no conservation of the active site residues, although it should be noted that the catalytic acid in GH67 enzymes is positioned on a highly mobile loop that can only be stabilized in the presence of ligands (11), which has some resonance with the mobile loop containing the catalytically significant residues Arg-328 and Asp-332 in BoAgu115A (Fig. 9B). In addition, the topology of the active site of the two enzymes is very different, comprising a deep pocket embedded in a rigid blind canyon (GH67 AguA) or a more accessible binding cleft (BoAgu115A), consistent with the exo and endo specificities of the respective glucuronidases. In general the catalytic apparatus is conserved in enzymes that are structurally related and display the same substrate specificity, but exhibit distinct modes of action; the introduction of exo activity is mediated by the modification of the substrate binding cleft of endo-acting enzymes such that the cleft is converted into a blind canyon or a tunnel (reviewed by Refs. 5 and 6). It is intriguing, therefore, that despite significant structural conservation, indicating an evolutionary link between the two glucuronidase families, the region of the enzymes that are most likely to be highly conserved, the catalytic apparatus, is clearly different in GH67 and GH115. The evolutionary selection pressures that led to such diversity in the active site of structurally and functionally related enzymes families are currently unclear.

FIGURE 9.

Comparison of the active site of BoAgu115A with a GH67 α-glucuronidase. Panel A shows an overlay of a protomer of BoAgu115A (green) with AguA, a GH67 α-glucuronidase (magenta; PDB code 1MQQ) from G. stearothermophilus (11). The position of the bound GlcA from BoAgu115A and AguA are circled. Panel B shows an overlay of the active site of the two enzymes depicted in panel A in schematic format with the key catalytic and sugar binding residues displayed as sticks. The residues in which the carbons are colored green (apo form of BoAgu115A; see Fig. 6 for the rationale for showing residues from the two structures) are from the GH115 enzyme and amino acids with carbons shown in magenta from the GH67 glucuronidase. The carbons of the GlcA in complex with BoAgu115A and the GlcA bound to AguA are shown in salmon pink and slate blue, respectively, in both panels. All oxygens and nitrogens are shown in red and dark blue, respectively.

Conclusions

This report reveals the first structure of a GH115 enzyme, identifying a likely distant evolutionary link to GH67, the other major family of α-glucuronidases. The locations of the residues that contribute to activity indicate that the enzyme undergoes a substantial conformational change to assemble a functional catalytic apparatus. It is interesting to note that despite complete conservation of the catalytically important amino acids in seven GH115 proteins, only BoAgu115A was shown to display activity (against glucuronoxylan). Although it is possible that the other six B. ovatus GH115 proteins are not catalytically active, a more likely explanation is that their target uronic acid-containing substrates are not glucuronoxylan, suggesting that GH115 is a poly-specific family.

This work was supported by Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC) Grant BB/G016240/1 BBSRC Sustainable Bioenergy Centre (BSBEC) Cell Wall Sugars Programme and Wellcome Trust Grant WT097907MA.

- PACE

- polysaccharide analysis using carbohydrate gel electrophoresis.

REFERENCES

- 1. Himmel M. E., Bayer E. A. (2009) Lignocellulose conversion to biofuels. Current challenges, global perspectives. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 20, 316–317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hooper L. V., Midtvedt T., Gordon J. I. (2002) How host-microbial interactions shape the nutrient environment of the mammalian intestine. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 22, 283–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bergman E. N. (1990) Energy contributions of volatile fatty acids from the gastrointestinal tract in various species. Physiol. Rev. 70, 567–590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kau A. L., Ahern P. P., Griffin N. W., Goodman A. L., Gordon J. I. (2011) Human nutrition, the gut microbiome and the immune system. Nature 474, 327–336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gilbert H. J., Stålbrand H., Brumer H. (2008) How the walls come crumbling down. Recent structural biochemistry of plant polysaccharide degradation. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 11, 338–348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gilbert H. J. (2010) The biochemistry and structural biology of plant cell wall deconstruction. Plant Physiol. 153, 444–455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cantarel B. L., Coutinho P. M., Rancurel C., Bernard T., Lombard V., Henrissat B. (2009) The Carbohydrate-Active EnZymes database (CAZy). An expert resource for Glycogenomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, D233–D238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Brett C. T., Waldren K. (1996) Physiology and Biochemistry of Plant Cell Walls. Topics in Plant Functional Biology, Chapman and Hall, London [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nagy T., Nurizzo D., Davies G. J., Biely P., Lakey J. H., Bolam D. N., Gilbert H. J. (2003) The α-glucuronidase, GlcA67A, of Cellvibrio japonicus utilizes the carboxylate and methyl groups of aldobiouronic acid as important substrate recognition determinants. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 20286–20292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nurizzo D., Nagy T., Gilbert H. J., Davies G. J. (2002) The structural basis for catalysis and specificity of the Pseudomonas cellulosa α-glucuronidase, GlcA67A. Structure 10, 547–556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Golan G., Shallom D., Teplitsky A., Zaide G., Shulami S., Baasov T., Stojanoff V., Thompson A., Shoham Y., Shoham G. (2004) Crystal structures of Geobacillus stearothermophilus alpha-glucuronidase complexed with its substrate and products. Mechanistic implications. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 3014–3024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ryabova O., Vrsanská M., Kaneko S., van Zyl W. H., Biely P. (2009) A novel family of hemicellulolytic α-glucuronidase. FEBS Lett. 583, 1457–1462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tenkanen M., Siika-aho M. (2000) An α-glucuronidase of Schizophyllum commune acting on polymeric xylan. J. Biotechnol. 78, 149–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kolenová K., Ryabova O., Vrsanská M., Biely P. (2010) Inverting character of family GH115 α-glucuronidases. FEBS Lett. 584, 4063–4068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fujimoto Z., Ichinose H., Biely P., Kaneko S. (2011) Crystallization and preliminary crystallographic analysis of the glycoside hydrolase family 115 α-glucuronidase from Streptomyces pristinaespiralis. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. F Struct. Biol. Cryst. Commun. 67, 68–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Martens E. C., Lowe E. C., Chiang H., Pudlo N. A., Wu M., McNulty N. P., Abbott D. W., Henrissat B., Gilbert H. J., Bolam D. N., Gordon J. I. (2011) Recognition and degradation of plant cell wall polysaccharides by two human gut symbionts. PLoS Biol. 9, e1001221 (1001221–1001216) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Martens E. C., Koropatkin N. M., Smith T. J., Gordon J. I. (2009) Complex glycan catabolism by the human gut microbiota. The Bacteroidetes Sus-like paradigm. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 24673–24677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hogg D., Pell G., Dupree P., Goubet F., Martín-Orúe S. M., Armand S., Gilbert H. J. (2003) The modular architecture of Cellvibrio japonicus mannanases in glycoside hydrolase families 5 and 26 points to differences in their role in mannan degradation. Biochem. J. 371, 1027–1043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Charnock S. J., Spurway T. D., Xie H., Beylot M. H., Virden R., Warren R. A., Hazlewood G. P., Gilbert H. J. (1998) The topology of the substrate binding clefts of glycosyl hydrolase family 10 xylanases are not conserved. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 32187–32199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gilbert H. J., Hazlewood G. P., Laurie J. I., Orpin C. G., Xue G. P. (1992) Homologous catalytic domains in a rumen fungal xylanase. Evidence for gene duplication and prokaryotic origin. Mol. Microbiol. 6, 2065–2072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Vardakou M., Dumon C., Murray J. W., Weiner D. P., Juge N., Lewis R. J., Gilbert H. J., Flint J. E. (2008) Understanding the structural basis for substrate and inhibitor recognition in eukaryotic GH11 xylanases. J. Mol. Biol. 375, 1293–1305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pell G., Taylor E. J., Gloster T. M., Turkenburg J. P., Fontes C. M., Ferreira L. M., Nagy T., Clark S. J., Davies G. J., Gilbert H. J. (2004) The mechanisms by which family 10 glycoside hydrolases bind decorated substrates. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 9597–9605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mortimer J. C., Miles G. P., Brown D. M., Zhang Z., Segura M. P., Weimar T., Yu X., Seffen K. A., Stephens E., Turner S. R., Dupree P. (2010) Absence of branches from xylan in Arabidopsis gux mutants reveals potential for simplification of lignocellulosic biomass. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 17409–17414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Goubet F., Jackson P., Deery M. J., Dupree P. (2002) Polysaccharide analysis using carbohydrate gel electrophoresis. A method to study plant cell wall polysaccharides and polysaccharide hydrolases. Anal. Biochem. 300, 53–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Leslie A. G. W., Powell H. R. (2007) Processing diffraction data with Mosflm. Evolving Methods for Macromolecular Crystallography. NATO Science Series 245, 41–51 [Google Scholar]

- 26. Evans P. (2006) Scaling and assessment of data quality. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 62, 72–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sheldrick G. M. (2010) Experimental phasing with SHELXC/D/E. Combining chain tracing with density modification. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 479–485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Winn M. D., Ballard C. C., Cowtan K. D., Dodson E. J., Emsley P., Evans P. R., Keegan R. M., Krissinel E. B., Leslie A. G., McCoy A., McNicholas S. J., Murshudov G. N., Pannu N. S., Potterton E. A., Poweell H. R., Read R. J., Vagin A., Wilson K. S. (2011) Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developments. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 67, 235–242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cowtan K. (2006) The Buccaneer software for automated model building. 1. Tracing protein chains. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 62, 1002–1011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Emsley P., Lohkamp B., Scott W. G., Cowtan K. (2010) Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 486–501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nicholls R. A., Long F., Murshudov G. N. (2012) Low-resolution refinement tools in REFMAC5. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 68, 404–417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Vagin A., Teplyakov A. (1997) MOLREP: an automated program for molecular replacement. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 30, 1022–1025 [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chen V. B., Arendall W. B., Headd J. J., Keedy D. A., Immormino R. M., Kapral G. J., Murray L. W., Richardson J. S., Richardson D. C. (2010) MolProbity. All-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 12–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cuskin F., Flint J. E., Gloster T. M., Morland C., Baslé A., Henrissat B., Coutinho P. M., Strazzulli A., Solovyova A. S., Davies G. J., Gilbert H. J. (2012) How nature can exploit nonspecific catalytic and carbohydrate binding modules to create enzymatic specificity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 20889–20894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Biely P., Vrsanská M., Tenkanen M., Kluepfel D. (1997) Endo-β-1,4-xylanase families. Differences in catalytic properties. J. Biotechnol. 57, 151–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. McKee L. S., Peña M. J., Rogowski A., Jackson A., Lewis R. J., York W. S., Krogh K. B., Viksø-Nielsen A., Skjøt M., Gilbert H. J., Marles-Wright J. (2012) Introducing endo-xylanase activity into an exo-acting arabinofuranosidase that targets side chains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 6537–6542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Koivula A., Ruohonen L., Wohlfahrt G., Reinikainen T., Teeri T. T., Piens K., Claeyssens M., Weber M., Vasella A., Becker D., Sinnott M. L., Zou J. Y., Kleywegt G. J., Szardenings M., Ståhlberg J., Jones T. A. (2002) The active site of cellobiohydrolase Cel6A from Trichoderma reesei. The roles of aspartic acids D221 and D175. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124, 10015–10024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Brás J. L., Cartmell A., Carvalho A. L., Verzé G., Bayer E. A., Vazana Y., Correia M. A., Prates J. A., Ratnaparkhe S., Boraston A. B., Romão M. J., Fontes C. M., Gilbert H. J. (2011) Structural insights into a unique cellulase fold and mechanism of cellulose hydrolysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 5237–5242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Montanier C., van Bueren A. L., Dumon C., Flint J. E., Correia M. A., Prates J. A., Firbank S. J., Lewis R. J., Grondin G. G., Ghinet M. G., Gloster T. M., Herve C., Knox J. P., Talbot B. G., Turkenburg J. P., Kerovuo J., Brzezinski R., Fontes C. M., Davies G. J., Boraston A. B., Gilbert H. J. (2009) Evidence that family 35 carbohydrate binding modules display conserved specificity but divergent function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 3065–3070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hidaka M., Nishimoto M., Kitaoka M., Wakagi T., Shoun H., Fushinobu S. (2009) The crystal structure of galacto-N-biose/lacto-N-biose I phosphorylase. A large deformation of a TIM barrel scaffold. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 7273–7283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Litzinger S., Fischer S., Polzer P., Diederichs K., Welte W., Mayer C. (2010) Structural and kinetic analysis of Bacillus subtilis N-acetylglucosaminidase reveals a unique Asp-His dyad mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 35675–35684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hehemann J. H., Smyth L., Yadav A., Vocadlo D. J., Boraston A. B. (2012) Analysis of keystone enzyme in agar hydrolysis provides insight into the degradation (of a polysaccharide from) red seaweeds. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 13985–13995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]