Abstract

Background:

A single bout of exercise improves postprandial glycemia and insulin sensitivity in prediabetic patients; however, the impact of exercise intensity is not well understood. The present study compared the effects of acute isocaloric moderate (MIE) and high-intensity (HIE) exercise on glucose disposal and insulin sensitivity in prediabetic adults.

Methods:

Subjects (n = 18; age 49 ± 14 y; fasting glucose 105 ± 11 mg/dL; 2 h glucose 170 ± 32 mg/dL) completed a peak O2 consumption/lactate threshold (LT) protocol plus three randomly assigned conditions: 1) control, 1 hour of seated rest, 2) MIE (at LT), and 3) HIE (75% of difference between LT and peak O2 consumption). One hour after exercise, subjects received an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT). Plasma glucose, insulin, and C-peptide concentrations were sampled at 5- to 10-minute intervals at baseline, during exercise, after exercise, and for 3 hours after glucose ingestion. Total, early-phase, and late-phase area under the glucose and insulin response curves were compared between conditions. Indices of insulin sensitivity (SI) were derived from OGTT data using the oral minimal model.

Results:

Compared with control, SI improved by 51% (P = .02) and 85% (P < .001) on the MIE and HIE days, respectively. No differences in SI were observed between the exercise conditions (P = .62). Improvements in SI corresponded to significant reductions in the glucose, insulin, and C-peptide area under the curve values during the late phase of the OGTT after HIE (P < .05), with only a trend for reductions after MIE.

Conclusion:

These results suggest that in prediabetic adults, acute exercise has an immediate and intensity-dependent effect on improving postprandial glycemia and insulin sensitivity.

Prediabetes is characterized by impaired glucose tolerance (IGT), (ie, a plasma glucose >140 mg/dL and <200 mg/dL 2 hours after a 75 g oral glucose challenge) or impaired fasting glucose (fasting glucose between 100 and 126 mg/dL). Impaired glucose tolerance in particular has emerged as an independent predictor of future adverse cardiovascular events (1, 2), and approximately 50% of adults with IGT progress to type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM2) over their life span (3).

Regular aerobic exercise is the cornerstone treatment for the delay and/or prevention of DM2, due in part to its transient effects on postprandial metabolism and skeletal muscle insulin sensitivity that can last upward of approximately 48 hours after the last exercise bout (4). Current American Diabetes Association (ADA) guidelines recommend that all prediabetic adults engage in moderate-intensity physical activity for at least 150 minutes or vigorous-intensity physical activity for at least 90 minutes each week with no more than 48 hours separating bouts (4, 5). However, the desired clinical outcomes may differ, depending on whether one follows the moderate-intensity physical activity vs vigorous-intensity physical activity recommendations. Several recent studies have shown greater improvements in the acute cardiometabolic adaptations to individualized high-intensity exercise (HIE) compared with moderate-intensity exercise (MIE), particularly when total energy expenditure is equated (6–8).

The comparative effects of acute MIE and HIE on postprandial metabolism are equivocal as most previous studies have evaluated glucose and insulin in response to a single exercise intensity (commonly in response to low-moderate intensity) (8–13). When measured 12–24 hours afterward, a single bout of either moderate or HIE has been shown to improve glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity in the postprandial period (11, 12, 14–16). When glucose and insulin responses to a mixed meal or oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) are measured closer to the cessation of exercise, the literature is less clear, with some studies reporting improvements in glucose and insulin responses (17, 18), whereas others reporting no change or exaggerated glucose and insulin responses (10, 19). To our knowledge, no previous studies have attempted to compare the effects of isocaloric MIE and HIE on glucose and insulin responses to an OGTT administered 1 hour after exercise in prediabetic subjects.

The present study examined the effects of acute isocaloric MIE and HIE, compared with a no-exercise control condition on the exercise, postexercise, and 3-hour OGTT glucose and insulin responses in prediabetic adults. It was hypothesized that acute exercise would improve the postprandial metabolic responses to the OGTT, and at an equivalent caloric output, HIE would be more effective than MIE due to improved insulin sensitivity.

Materials and Methods

Study subjects

The Institutional Review Board at the University of Virginia approved the study and subjects provided written informed consent prior to participation.

Eighteen middle-aged men and women who met the ADA criteria for prediabetes (5) volunteered and completed the present study. Prediabetes was defined as a fasting plasma glucose greater than 100 mg/dL but below 126 mg/dL and/or IGT; with plasma glucose between 140 and 200 mg/dL 2 hours after a 75-g oral glucose load, and/or glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) values between 5.7% and 6.4%. Subjects were sedentary (exercise <30 min/d, <3 d/wk). All procedures were performed in the University of Virginia Clinical Research Unit (CRU) at approximately 8:00 am after a 10- to 12-hour overnight fast.

Screening and baseline tests

Screening subjects reported to the CRU for assessment of fasting plasma glucose, glucose tolerance, and HbA1c. Upon arrival, blood pressure was measured in the seated position, and whole blood was drawn for measurement of liver function, complete blood count, uric acid, HbA1c, hematocrit, urea nitrogen, and fasting lipid profile (total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein, low-density lipoprotein, and triglycerides). Subjects were then administered a standard 75-g, 2-hour OGTT. Plasma glucose was sampled at baseline and at 30-minute intervals during the OGTT. Subjects meeting one or more criteria for prediabetes described above were invited to continue participation in the study. Exclusion criteria included a history of ischemic heart disease, uncontrolled hypertension, diabetes, pulmonary or musculoskeletal limitations to exercise, and pregnancy or breastfeeding.

Body composition

Body composition was measured using air displacement plethysmography (Cosmed) corrected for thoracic gas volume as previously described (7). Waist circumference measurements were taken in triplicate to the nearest 0.1 cm using a nonelastic measuring tape at the level of the umbilicus.

Maximal oxygen consumption/lactate threshold

Subjects completed a continuous peak O2 consumption (VO2peak)/lactate threshold (LT) bicycle ergometer protocol. The initial power output (PO) was 20 W, and the power output was increased by 15 W every 3 minutes until volitional exhaustion. Metabolic data were collected during the protocol using standard open-circuit spirometric techniques (Viasys Vmax Encore), and heart rate was assessed electrocardiographically. VO2peak was chosen as the highest O2 consumption (VO2) attained during the exercise protocol. An indwelling venous catheter was inserted in a forearm vein, and blood samples were taken at rest and at the end of each exercise stage for the measurement of blood lactate concentration (YSI 2700; Yellow Springs Instruments). The LT was determined from the blood lactate-power output relationship and was defined as the highest power output attained prior to the curvilinear increase in blood lactate concentrations above baseline (7). Individual plots of VO2 vs PO allowed for the determination of the PO associated with the LT.

Study protocol

Each subject served as their own control. Subjects were admitted to the CRU at approximately 8:00 am on three separate randomly assigned occasions (control, MIE, and HIE). Subjects were asked to refrain from alcohol, caffeine, and cigarette smoking and vigorous physical activity for at least 72 hours prior to their admission. Three-day food diaries were administered prior to each admission to control for prestudy diet (see below). Premenopausal women were studied during the early follicular phase (d 2–8) of the menstrual cycle. Subjects completed all trials within a maximum time span of 3 months.

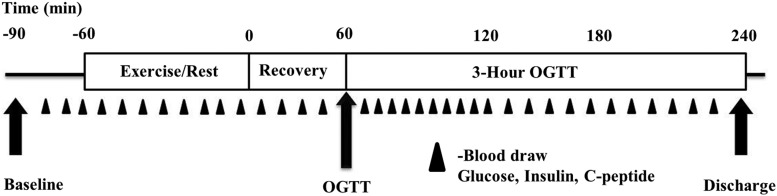

Figure 1 presents the study timeline. On the morning of each admission, an iv catheter was placed in the subject's dominant arm or hand. Blood samples were obtained in 10-minute intervals over 30 minutes from the indwelling venous catheter for measurement of glucose, insulin, and C-peptide. Subjects completed the following condidtions with order randomized: Control (C), moderate intensity, and high intensity exercise.

Figure 1.

Study time line.

The control session included no exercise and the subjects rested in a seated position for one hour from time −6- to time 0 (see Figure 1).

In the MIE session, subjects performed 200 kcal of bicycle ergometer exercise at the power output and VO2 associated with the individual's LT (the time required to expend 200 kcal was calculated using indirect calorimetry and exercise duration was adjusted in real time based on the subjects VO2 and respiratory exchange ratio values). We chose to express exercise intensity relative to the LT on the basis of the following: 1) exercise above the LT acutely increases GH and catecholamine release (both of which impact postexercise substrate use) (7, 20); 2) the LT is an important marker of submaximal fitness and a strong predictor of endurance performance (21); and 3) our group has shown that when prescribing exercise based on percentage maximum oxygen consumption, some individuals will be working below the LT, whereas others will be working above the LT (21).

In the HIE session subjects performed 200 kcal of bicycle ergometer exercise at the PO and VO2 associated with 75% of the difference between the LT and the peak PO.

Metabolic, heart rate (HR), and data on the ratings of perceived exertion were monitored during each exercise session.

After exercise or rest conditions, subjects returned to bed. Blood was sampled for plasma glucose, insulin, and C-peptide in 10-minute intervals during exercise and during a 1-hour recovery period.

Oral glucose tolerance test

One hour after stopping exercise or rest (in control condition), subjects received a 3-hour, 75-g OGTT. Blood was drawn at 5-miunte intervals during the first hour and every 10 minutes during the second and third hour of the OGTT.

Dietary control

Subjects consumed a moderate carbohydrate diet (∼200 g of carbohydrate per day) for 72 hours prior to study. A simple food diary was used to record the number of servings of carbohydrate ingested each day, and the diary was returned to the study team on the morning of each study admission.

Assays

Centrifugation of whole blood was performed immediately after sample collection for plasma glucose analysis. Samples for measurement of insulin and C-peptide were stored at −80°C until measured using a chemiluminescent immunometric assay (Immulite 2000; Diagnostic Products Corp). The insulin assay sensitivity was 2 μIU/mL, and the intra- and interassay coefficients of variation were 3.5% and 5.6%, respectively. The C-peptide assay sensitivity was 0.5 ng/mL, and the intra- and interassay coefficients of variation were 2.0% and 3.5%, respectively.

Calculations

The total (3 h), early-phase (first hour of the OGTT), and late-phase (last 2 h of the OGTT) area under the curve (AUC) values for the glucose, insulin, C-peptide, and insulin secretion responses were calculated using trapezoidal reconstruction. The insulin response to the rise in glucose (insulinogenic index) was calculated as follows: [(insulin at 30 min) − (insulin at 0 min)]/[(glucose at 30 min) − (glucose at 0 min)]. Indices of insulin sensitivity were calculated using the oral glucose and insulin minimal model described previously (22). Briefly, the glucose appearance rate during a 3-hour OGTT was reconstructed into a series of piece-wise linear functions with a set number of break points and with frequently sampled glucose and insulin data inputs, and those break point parameters as well as the model parameters were fitted by constrained nonlinear optimization (22).

Statistical analysis

Fasting plasma glucose, insulin and C-peptide concentrations were analyzed via repeated-measures ANOVA with the study admission serving as the primary between-factor comparison. Pairwise comparisons were conducted based on linear contrasts of the least squares means.

The effects of exercise intensity on metabolic responses in the recovery period were examined using random coefficient regression, with the admission and the recovery assessment time serving as the random coefficient regression predictor variables. The intercepts and slope parameters of the regression profiles were simultaneously compared across the three study admissions via a multiple numerator degree of F tests, and individual intercept and slope parameters were compared between study admissions in a pairwise manner.

The effects of exercise intensity on the metabolic responses to oral glucose were examined via repeated-measure analysis of covariance (ANCOVA). The individual values for glucose, insulin, and C-peptide AUC (total AUC, early phase AUC, and late phase AUC) were rescaled to the natural logarithmic scale for the data analyses. The ANCOVA model factor was the admission, and the ANCOVA model covariate was the final response value measured in the recovery period, which served as an adjustment factor. The primary factor in determining the sample size for the present study was our ability to detect differences in the geometric mean 3-hour glucose AUC between the two exercise conditions. Allowing for a 20% dropout rate, 19 subjects were required to detect a 15% difference in total glucose AUC between MIE and HIE with 80% power. With eight subjects we were powered to detect a 20% difference in total glucose AUC between MIE and HIE with 80% power.

The analyses assumed that the values of missing data points were known. For missing data we averaged the last known value and the value immediately following the missing data point. A P ≤ .05 decision rule was used as the null hypothesis rejection criterion for the individual adjusted statistical tests. SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc) was used to conduct the data analyses.

Results

Subject characteristics are summarized in Table 1. As per study design, subjects were overweight or obese and of low cardiorespiratory fitness.

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics of the Study Subjects (Mean ± SD)

| Variable | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|

| Total number, M/F (n/n) | 18 (9/9) |

| Age, y | 48.6 ± 14 |

| Weight, kg | 94.6 ± 21 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 32.1 ± 7 |

| Waist circumference, cm | 108.8 ± 12 |

| Body fat, % | 40.8 ± 6 |

| FM, kg | 39.1 ± 12 |

| FFM, kg | 55.6 ± 11 |

| Fasting glucose, mg/dL | 105.4 ± 11 |

| Fasting insulin, μIU/mL | 11.6 ± 9 |

| Fasting C-peptide, ng/mL | 3.1 ± 0.9 |

| 2-Hour glucose, mg/dL | 169.9 ± 32 |

| HbA1c, % | 5.7 ± 0.4 |

| VO2peak, mL/kg · min | 22.9 ± 5 |

| VO2peak, mL/kg FFM per min | 38.6 ± 7 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; F, females; FFM, fat-free mass; FM, fat mass; 2-hour glucose, plasma glucose level 2 hours after an oral glucose challenge; M, males.

Fasting metabolism

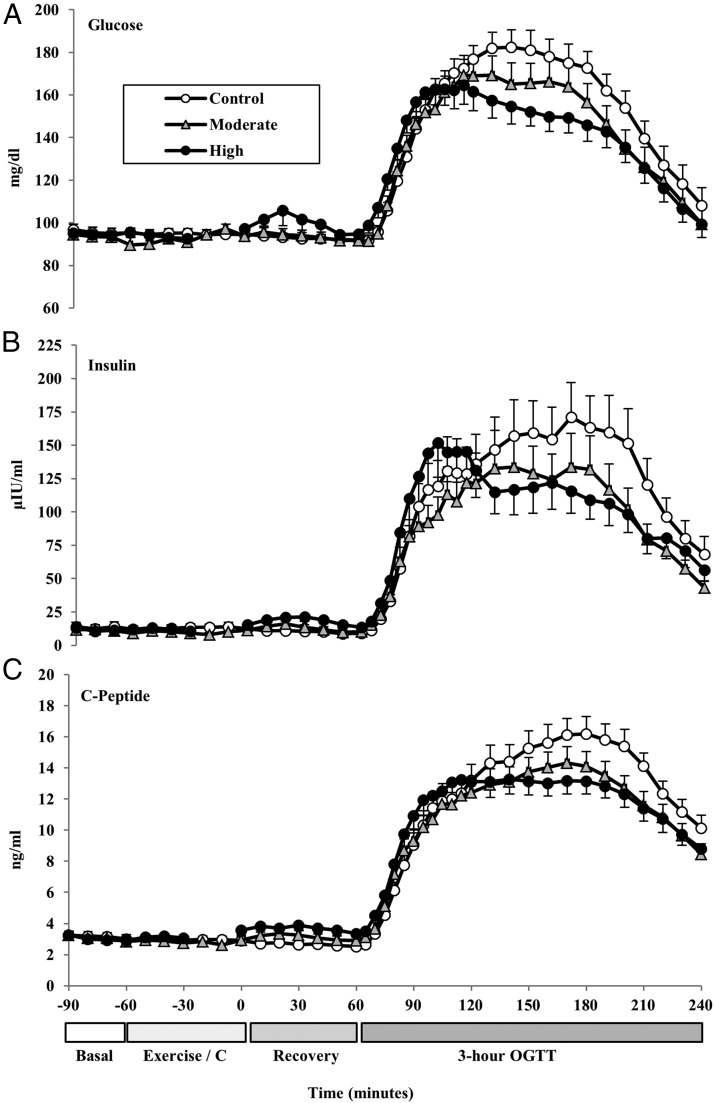

Fasting plasma glucose, insulin, and C-peptide concentrations were not significantly different across the 3 study days (aggregate mean values for glucose, 94.7 ± 9.5 mg/dL, P = .85; insulin, 12.3 ± 10.5 μIU/mL, P = .90; C-peptide, 3.1 ± 1.0 ng/mL, P = .94; Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Mean(±SE) plasma glucose (A), insulin (B), and C-peptide (C) response profiles by sampling time point (every 5 to 10 min intervals) at baseline, during exercise (or rest), during recovery, and during the 3-hour, 75-g OGTT.

Constant load exercise protocols

Exercise parameters from the constant load sessions are presented in Table 2. MIE corresponded to 40.1 ± 9 minutes of cycling at approximately 50% VO2peak [∼30% peak power output (PPO)]. HIE was performed for 23.8 ± 5 minutes at approximately 83% VO2peak (∼80% PPO). Total work was not different between the exercise conditions (P = .59, Table 2).

Table 2.

Exercise Parameters (Mean ± SD)

| Variable | Moderate Intensity | High Intensity | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Power output, W (% peak power) | 37.2 ± 17 (30.0%) | 91.9 ± 23 (80%) | <.001 |

| VO2, mL/kg · min , (% VO2peak) | 11.5 ± 3.4 (50%) | 19.1 ± 5.0 (83%) | <.001 |

| Heart rate, beats/min (% peak HR) | 107.6 ± 13 (69%) | 143.2 ± 24 (91%) | <.001 |

| Borg-RPE | 10.5 ± 2 | 15.2 ± 2 | <.001 |

| Duration, min | 40.1 ± 9 | 23.8 ± 5 | <.001 |

| Energy expenditure, kcal | 182.0 ± 19 | 177.2 ± 26 | .59 |

Abbreviations: HR, heart rate; RPE, ratings of perceived exertion on a BORG 6–20 scale. Note exercise energy expenditure (kilocalories) calculations are based on n = 14; incomplete metabolic data were collected on four subjects.

Effects of exercise intensity on glucose, insulin, and C-peptide in the exercise recovery period

The mean values for glucose, insulin, and C-peptide during the 1-hour recovery period after exercise/control and prior to the OGTT are presented in Figure 2, A–C. HIE resulted in a transient postexercise rise in glucose and insulin (Figure 2, A and B). Pairwise comparison of the marginal regression profiles showed that blood glucose concentrations increased during the first 30 minutes of the recovery period after HIE, remaining higher than both control (P < .001) and MIE (P < .001). Insulin and C-peptide responses during the first 30 minutes of recovery after HIE mirrored the glucose response. Glucose concentrations returned to baseline values by the end of the recovery period. Insulin concentrations at the end of the recovery period were higher after high intensity compared with control values (on average 9.0 μIU/mL higher; P = .05).

Effects of exercise intensity on the glycemic response to an OGTT

Blood glucose increased above baseline values throughout the duration of the 3-hour OGTT (Figure 2A). The total 3-hour glucose AUC (adjusted for baseline and recovery values) was not significantly different from control in the MIE condition (P = .99) but tended to be lower (8%) after HIE compared with control (P = .17). Total glucose AUC did not differ between exercise conditions (MIE vs HIE, P = .99).

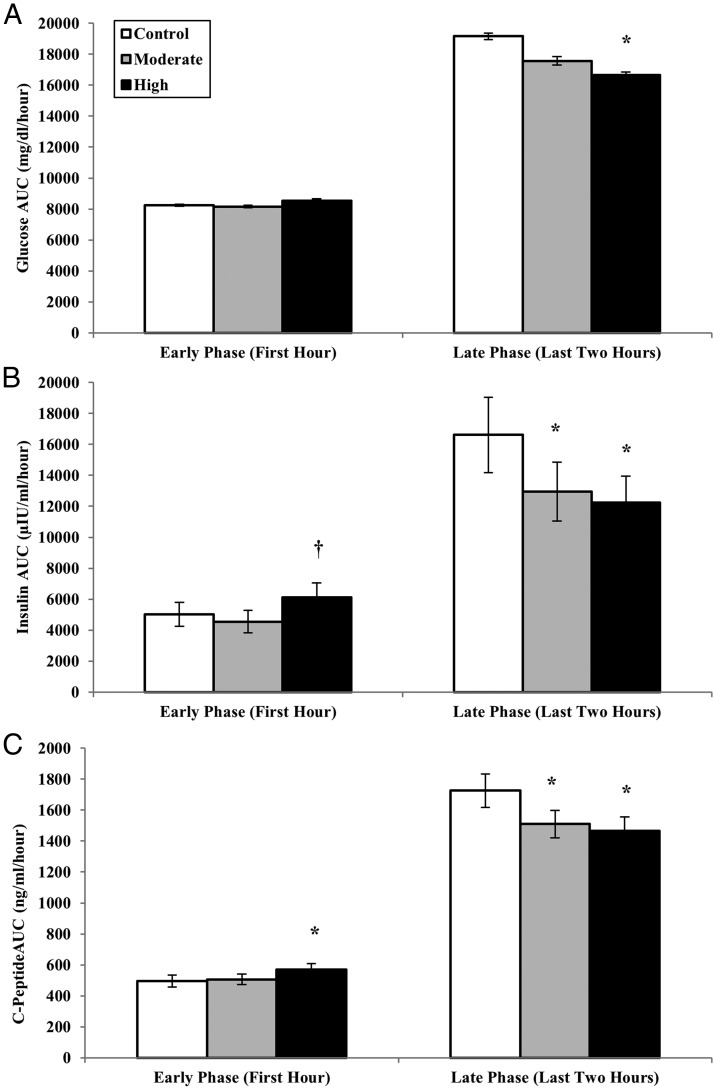

As shown in Figure 3A, early-phase glucose responses were not different between the conditions (P = .99). Compared with the control day, the late-phase glucose AUC was 13% lower after HIE (P = .002) and trended 8% lower after MIE (P = .10; Figure 3A). Late-phase glucose responses did not differ between the exercise conditions (MIE vs HIE, P = .54).

Figure 3.

Mean (±SE) incremental AUC for the glucose (A), insulin (B), and C-peptide (C) responses to a 3-hour OGTT performed 1 hour after the cessation of acute isocaloric moderate and HIE, compared with a no-exercise control condition. AUC values represent first-phase (first hour during the OGTT) and late-phase segments (second and third hour of the OGTT). *, Significantly different from control (P < .05). †, significantly different from MIE (P < .05).

Both moderate- and high-intensity exercise significantly lowered the 2-hour glucose values (control = 172.8 ± 7.7 mg/dL; moderate = 156.6 ± 8.8 mg/dL; high = 145.9 ± 7.6; mg/dL; control vs moderate, P = .002; control vs high, P < .001). Of the 15 subjects with IGT at baseline, seven (47%) had normal postprandial glucose responses after HIE, whereas five (33%) had normal responses after MIE.

Effects of exercise intensity on the insulin responses to an OGTT

The total 3-hour AUC values for insulin and C-peptide were not different between conditions (repeated measures ANOVA main effect for condition: insulin, P = .20; C-peptide, P = .34). The insulinogenic index (ie, the first phase insulin response to the initial rise in glucose) was not different between conditions (insulinogenic index, microinternational units per milliliter per milligram per deciliter: control = 2.21 ± 0.5; MIE = 1.73 ± 0.4; HIE = 2.18 ± 0.6; P > .05); however, the first-phase insulin AUC was significantly greater after HIE compared with MIE (P = .009; Figure 3B). The second-phase insulin AUC was 26% lower after HIE compared with control (P = .01) and was 22% lower after MIE compared with control (P = .01; Figure 3B). The difference in second-phase insulin AUC between exercise conditions was not significant (P = .99). Similar to the insulin response, second-phase C-peptide AUC was significantly lower after both HIE (P = .001; Figure 3C) and MIE compared with control (P = .02; Figure 3C).

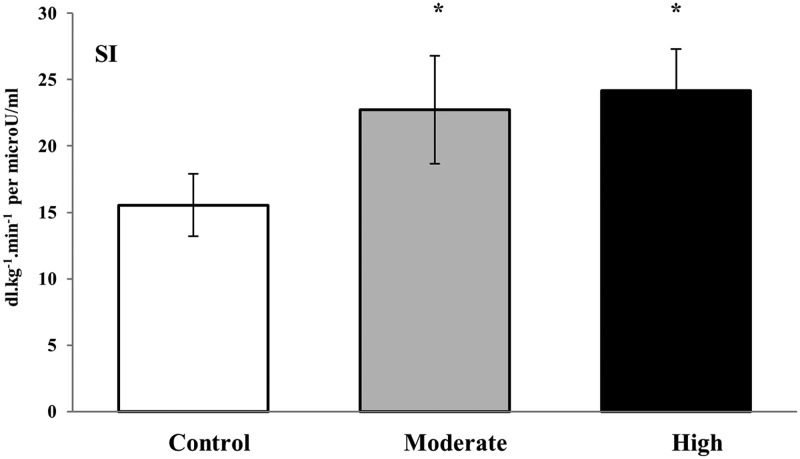

Effects of exercise intensity on insulin action

Insulin sensitivity increased on average by 51% (P < .02) and 85% (P < .001) after moderate- and high-intensity exercise, respectively, compared with the control trial (Figure 4). The difference in insulin sensitivity improvement between exercise conditions did not reach statistical significance (P = .62).

Figure 4.

Mean (±SE) minimal derived estimates of insulin sensitivity in response to acute isocaloric high and MIE compared with a no-exercise control condition. *, Significantly different from control (P < .05).

Discussion

The major findings of the present study are that acute HIE and MIE effectively improved the late-phase postprandial glucose and insulin responses to an OGTT, compared with a no-exercise control (Figures 2 and 3) and that both MIE and HIE are beneficial for improving postprandial insulin sensitivity measured 1 hour after the cessation of exercise (Figure 4). Although the differences between exercise conditions did not reach statistical significance, our data tend to suggest that HIE conveys greater postprandial benefits compared with an isocaloric bout of MIE.

Postexercise metabolism

In the present study, glucose and insulin concentrations peaked approximately 30 minutes into the recovery period after HIE and then decreased to near basal levels 1 hour after exercise. It is well known that HIE is marked by a 14- to 18-fold increase in plasma catecholamine concentration (23). Circulating catecholamines are potent stimulators of skeletal muscle glycogenolysis and inhibit pancreatic insulin secretion. During HIE, glucose production exceeds glucose utilization, resulting in a net increase in plasma glucose, whereas insulin remains near basal levels or increase slightly (23). Recovery from HIE is characterized by a rapid decrease in plasma norepinephrine and epinephrine, which lessens α-adrenergic inhibition of insulin secretion, allowing a compensatory insulin response to bring plasma glucose levels back to basal levels. The postexercise hyperglycemic/hyperinsulinemic response to HIE is thought to create an environment favorable for efficient glycogen resynthesis. Relevant to the present study, it has been shown that the postexercise muscle glycogen resynthesis rates after an acute bout of exercise are directly related to improvements in exercise-induced insulin sensitivity (24). Muscle glycogen resynthesis rates after HIE are typically higher than glycogen resynthesis rates after low MIE, partially due to greater recruitment of glycolytic-type II muscle fibers.

Effects of exercise intensity on the glycemic response to oral glucose

Compared with a nonexercising control condition, we observed improved postprandial glucose over the last 2 hours of the OGTT after HIE but not MIE. These results differ from previous studies in the literature comparing the glucose-lowering effects of continuous moderate and HIE in insulin-resistant subjects (9, 11, 25, 26). For example, when matched for caloric output, Manders et al (9) reported that an acute bout of high-intensity cycle ergometer exercise (70% PPO) was not more effective than MIE (35% PPO) for improving the 24-hour prevalence of hyperglycemia (as measured by continuous glucose monitoring) in a sample of subjects with type 2 diabetes. Postprandial glucose responses to standardized mixed meals consumed in free-living conditions measured approximately 3 hours after exercise (lunch) and approximately 8 hours after exercise (dinner) were significantly lower only after the dinner meal, with no differences observed between the exercise conditions. The authors suggested the glucose-lowering effects of exercise (either high or moderate intensity) may take some time to reach maximal effect, a conclusion also supported by two similar studies in the literature in subjects with DM2 (25, 26).

Data from the present study indicates that the glucose-lowering benefits of exercise may occur in as little as 1 hour after exercise. Differences between the results of the present study and those of Manders et al (9) may be attributed to the following facts: 1) our subjects performed the acute exercise sessions in the fasted state (vs 1 h postprandially), 2) the acute responses to exercise performed prior to a mixed meal may be different from when exercise is performed prior to an OGTT, 3) the time course of the acute glucose-lowering effects of exercise may be different in prediabetic adults compared to DM2 patients, and/or 4) variability in the responses may be attributed to differences in absolute or relative workloads. With regard to the latter, although the absolute workloads were lower than those used in the study by Manders et al (9) (37 W and 92 W vs 65 W and 130 W), relative workloads were similar (50% and 80% vs 65% and 85% VO2peak). Interestingly, in a subsequent analysis, our data suggest that even in unfit individuals, a higher endurance capacity (higher PO at the LT) is associated with greater improvements in glycemia and insulin sensitivity after exercise.

With respect to the timing of exercise relative to ingestion of an OGTT, several studies have reported an exacerbated glycemic response to oral glucose ingested in the period immediately (eg, 30–60 min) after exercise compared with 24 hours after exercise (10, 19, 27). Rose et al (19) reported that HIE exaggerated the total glycemic response to an OGTT administered 30 minute after exercise more than a single bout of MIE in a sample of trained men. The findings of the present study differ perhaps because we studied untrained prediabetic adults in whom clearly the total glycemic excursion is lower when acute HIE is performed 1 hour prior to refeeding with carbohydrate.

Effects of exercise intensity on the insulin responses to oral glucose

The effects of acute exercise on post-OGTT insulin responses are equivocal, with some studies showing a delayed or blunted insulin response to oral glucose ingested in the postexercise period (19, 27–31) and other studies showing no change or a hyperinsulinemic response (10, 32, 33). In the present study, HIE lowered the late-phase postprandial insulin response (25%–29% lower over both the second and third hours of the OGTT), whereas the late-phase, insulin-lowering effects of MIE were less pronounced and more variable.

Few studies in the literature have directly compared the effects of isocaloric exercise of varying intensity on the insulin responses to oral glucose, and although a cross-comparison of existing studies suggests that both moderate and HIE may be effective in reducing postprandial insulin levels (12, 18, 19, 34), there may be additional benefits exclusive to HIE (12, 28). For example, BenEzra et al (12) reported that when caloric expenditure was held constant, a single bout of high-intensity walking (∼70% VO2peak) for 50 minutes significantly reduced the postexercise insulin response to a 150-minute OGTT, whereas low-intensity walking (40% VO2peak; energy expenditure matched to high intensity condition) did not impact insulin AUC in a sample of untrained women. The authors speculated that the added benefit afforded by higher-intensity walking was likely due to greater carbohydrate use and muscle recruitment during exercise at 70% of VO2peak vs 40% VO2peak, resulting in improved postexercise insulin action, thus decreasing insulin requirements.

Effects of exercise intensity on insulin sensitivity

In support of our original hypothesis, whole-body insulin sensitivity as estimated using the oral minimal model was improved after both MIE and HIE. A well-known effect of acute exercise is to improve insulin action; however, it should be noted that most studies measure insulin action 12–24 hours after the bout (ie, the following day) (17, 28, 35–38) and rarely in the immediate postexercise period (10, 18, 19, 25, 39). The timing of the end of exercise and the start of the meal has potential implications for prediabetes and glycemic control. For example, meals consumed near the end of an exercise bout have been shown to modulate the insulin sensitivity response. When measured in the immediate period (eg, ∼30 min to 3 h after exercise), some studies have reported improved whole-body insulin sensitivity (18, 39), whereas others suggest no change or even impaired insulin sensitivity (10, 19). Given that many individuals consume a meal near the end of an exercise bout, understanding the postexercise response has clinical implications for postprandial glucose control in prediabetes.

Some investigators have suggested that refeeding carbohydrate immediately after exercise blunts the acute improvements in insulin action commonly observed after a single bout of aerobic exercise (36, 39). For example, Holtz et al (39) reported that insulin action was significantly blunted (and not different from a sedentary control condition) when all of the energy expended after a single bout of cycle exercise at 70% VO2peak was replaced with carbohydrate compared with a 15% increase in insulin action when only a fraction of the expended energy was replaced with carbohydrate (ie, carbohydrate deficit) (39). In contrast, the same group also reported that a single bout of cycle exercise (65% VO2peak followed by 10 × 30 sec high intensity sprints) enhanced insulin action (measured 12 h after exercise), even when expended energy was replaced by a carbohydrate meal given immediately after exercise compared with carbohydrate replaced 3 hours after exercise. Interestingly, the authors report that insulin action increased 44% when energy was replaced immediately after exercise, and only approximately 20% in the condition during which the meal was administered 3 hours after exercise (38).

It has recently been shown that the insulin profile phenotype is different for the impaired fasting glucose (IFG) vs IGT forms of prediabetes (40). Consequently, it is possible that the baseline characteristics of the prediabetic subjects in the present study may have been a source of variability in the observed insulin responses. Fourteen subjects in the present study had both IGT and IFG [combined glucose intolerance (CGI)], and one subject had IGT only and three subjects had IFG only on one or more testing occasions. When only subjects with CGI were analyzed (n = 14), virtually identical results were observed, suggesting that the defect accompanying CGI requires a late-phase (second phase) insulin response. We do not have enough data to indicate whether this would be the case for subjects who present with only IGT or IFG.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of the present study include recruitment of prediabetic subjects sharing a common etiology, comparison of calorically equivalent bouts of moderate and HIE consistent with the amount and duration of exercise recommended by the American College of Sports Medicine and the ADA for the prevention of DM2 (4, 5) and quantification of insulin sensitivity using the oral minimal model. Limitations include the intraindividual variation in glucose and insulin responses inherent in oral glucose tolerance testing and no direct measures of the postexercise counterregulatory response. It should be noted that the diet was standardized for the 3 days preceding the OGTT, and for women, the phase of the menstrual cycle was consistent between admissions, which may have decreased the variability associated with repeated OGTTs.

Conclusions

In summary, prior acute HIE decreases the postprandial glycemic and insulinemic responses to an oral glucose load. Furthermore, both moderate and HIE improved insulin sensitivity (51%–85%). Long-term training interventions will be required to investigate the effects of HIE on glycemic excursion and whether HIE training results in a reduced conversion of prediabetes to DM2.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the research subjects for their participation in the study. We also acknowledge helpful assistance from the nursing staff of the Clinical Research Unit at the University of Virginia Medical Center.

This work was supported by the Virginia Commonwealth Health Research Board and the National Institutes of Health (Grant NIH-RR00847).

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- ADA

- American Diabetes Association

- ANCOVA

- analysis of covariance

- AUC

- area under the curve

- CGI

- combined glucose intolerance

- CRU

- Clinical Research Unit

- DM2

- type 2 diabetes mellitus

- HbA1c

- glycosylated hemoglobin

- HIE

- high-intensity exercise

- HR

- heart rate

- IFG

- impaired fasting glucose

- IGT

- impaired glucose tolerance

- LT

- lactate threshold

- MIE

- moderate-intensity exercise

- OGTT

- oral glucose tolerance test

- PO

- power output

- PPO

- peak power output

- VO2

- O2 consumption

- VO2peak

- peak VO2.

References

- 1. Cavalot F, Petrelli A, Traversa M, et al. Postprandial blood glucose is a stronger predictor of cardiovascular events than fasting blood glucose in type 2 diabetes mellitus, particularly in women: lessons from the San Luigi Gonzaga Diabetes Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:813–819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Woerle HJ, Neumann C, Zschau S, et al. Impact of fasting and postprandial glycemia on overall glycemic control in type 2 diabetes: importance of postprandial glycemia to achieve target HbA1c levels. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2007;77:280–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cowie CC, Rust KF, Ford ES, et al. Full accounting of diabetes and pre-diabetes in the US population in 1988–1994 and 2005–2006. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:287–294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Colberg SR, Albright AL, Blissmer BJ, et al. Exercise and type 2 diabetes: American College of Sports Medicine and the American Diabetes Association: joint position statement. Exercise and type 2 diabetes. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010;42:2282–2303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. American Diabetes Association Standards of medical care in diabetes—2012. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:S11–S63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tjonna AE, Lee SJ, Rognmo O, et al. Aerobic interval training versus continuous moderate exercise as a treatment for the metabolic syndrome: a pilot study. Circulation. 2008;118:346–354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Irving BA, Davis CK, Brock DW, et al. Effect of exercise training intensity on abdominal visceral fat and body composition. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40:1863–1872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Babraj JA, Vollaard NB, Keast C, Guppy FM, Cottrell G, Timmons JA. Extremely short duration high intensity interval training substantially improves insulin action in young healthy males. BMC Endocr. Disord. 2009;9:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Manders RJ, Van Dijk JW, van Loon LJ. Low-intensity exercise reduces the prevalence of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010;42:219–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Weltman NY, Rynders CA, Gaesser GA, Weltman JY, Barrett EJ, Weltman A. Exercise intensity does not affect glucose disposal in euglycemic abdominally obese adults. Obes Metab Milan. 2010;6:86–93 [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bonen A, Ball-Burnett M, Russel C. Glucose tolerance is improved after low- and high-intensity exercise in middle-age men and women. Can J Appl Physiol. 1998;23:583–593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. BenEzra V, Jankowski C, Kendrick K, Nichols D. Effect of intensity and energy expenditure on postexercise insulin responses in women. J Appl Physiol. 1995;79:2029–2034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Colberg SR, Zarrabi L, Bennington L, et al. Postprandial walking is better for lowering the glycemic effect of dinner than pre-dinner exercise in type 2 diabetic individuals. J Am Med Directs Assoc. 2009;10:394–397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. DiPietro L, Dziura J, Yeckel CW, Neufer PD. Exercise and improved insulin sensitivity in older women: evidence of the enduring benefits of higher intensity training. J Appl Physiol. 2006;100:142–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hayashi Y, Nagasaka S, Takahashi N, et al. A single bout of exercise at higher intensity enhances glucose effectiveness in sedentary men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:4035–4040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kang J, Robertson RJ, Hagberg JM, et al. Effect of exercise intensity on glucose and insulin metabolism in obese individuals and obese NIDDM patients. Diabetes Care. 1996;19:341–349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hasson RE, Granados K, Chipkin S, Freedson PS, Braun B. Effects of a single exercise bout on insulin sensitivity in black and white individuals. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:E219–E223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hasson RE, Freedson PS, Braun B. Postexercise insulin action in African-American women. J Natl Med Assoc. 2006;98:1832–1839 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rose AJ, Howlett K, King DS, Hargreaves M. Effect of prior exercise on glucose metabolism in trained men. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2001;281:E766–E771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Weltman A, Wideman L, Weltman JY, Veldhuis JD. Neuroendocrine control of GH release during acute aerobic exercise. J Endocrinol Invest. 2003;26:843–850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Weltman A SD, Seip R, Schurrer R, Weltman J, Rutt R, Rogol A. Percentages of maximal heart rate, heart rate reserve and VO2max for determining endurance training intensity in male runners. Int J Sports Med. 1990;11:218–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dalla Man C, Yarasheski KE, Caumo A, et al. Insulin sensitivity by oral glucose minimal models: validation against clamp. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2005;289:E954–E959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Marliss EB, Vranic M. Intense exercise has unique, effects on both insulin release and its roles in glucoregulation: implications for diabetes. Diabetes. 2002;51:S271–S283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Goodyear LJ, Kahn BB. Exercise, glucose transport, and insulin sensitivity. Annu Rev Med. 1998;49:235–261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Larsen JJ, Dela F, Madsbad S, Galbo H. The effect of intense exercise on postprandial glucose homeostasis in type II diabetic patients. Diabetologia. 1999;42:1282–1292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Larsen JJ, Dela F, Kjaer M, Galbo H. The effect of moderate exercise on postprandial glucose homeostasis in NIDDM patients. Diabetologia. 1997;40:447–453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. King DS, Baldus PJ, Sharp RL, Kesl LD, Feltmeyer TL, Riddle MS. Time course for exercise-induced alterations in insulin action and glucose tolerance in middle-aged people. J Appl Physiol. 1995;78:17–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Heath GW, Gavin JR, Hinderliter JM, Hagberg JM, Bloomfield SA, Holloszy JO. Effects of exercise and lack of exercise on glucose-tolerance and insulin sensitivity. J Appl Physiol. 1983;55:512–517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. O'Gorman DJ, Del Aguila LF, Williamson DL, Krishnan RK, Kirwan JP. Insulin and exercise differentially regulate PI3-kinase and glycogen synthase in human skeletal muscle. J Appl Physiol. 2000;89:1412–1419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tuominen JA, Ebeling P, Koivisto VA. Exercise increases insulin clearance in healthy man and insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus patients. Clin Physiol. 1997;17:19–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. O'Connor AM, Pola S, Ward BM, Fillmore D, Buchanan KD, Kirwan JP. The gastroenteroinsular response to glucose ingestion during postexercise recovery. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2006;290:E1155–E1161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rogers MA, Yamamoto C, King DS, Hagberg JM, Ehsani AA, Holloszy JO. Improvement in glucose-tolerance after 1 wk of exercise in patients with mild NIDDM. Diabetes Care. 1988;11:613–618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Baynard T, Franklin RM, Goulopoulou S, Carhart R, Kanaley JA. Effect of a single vs multiple bouts of exercise on glucose control in women with type 2 diabetes. Metabolism. 2005;54:989–994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Young JC, Enslin J, Kuca B. Exercise intensity and glucose-tolerance in trained and nontrained subjects. J Appl Physiol. 1989;67:39–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Devlin JT, Hirshman M, Horton ED, Horton ES. Enhanced peripheral and splanchnic insulin sensitivity in NIDDM men after single bout of exercise. Diabetes. 1987;36:434–439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bogardus C, Thuillez P, Ravussin E, Vasquez B, Narimiga M, Azhar S. Effect of muscle glycogen depletion on invivo insulin action in man. J Clin Invest. 1983;72:1605–1610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mikines KJ, Sonne B, Farrell PA, Tronier B, Galbo H. Effect of physical exercise on sensitivity and responsiveness to insulin in humans. Am J Physiol. 1988;254:E248–E259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Stephens BR, Sautter JM, Holtz KA, Sharoff CG, Chipkin SR, Braun B. Effect of timing of energy and carbohydrate replacement on post-exercise insulin action. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2007;32:1139–1147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Holtz KA, Stephens BR, Sharoff CG, Chipkin SR, Braun B. The effect of carbohydrate availability following exercise on whole-body insulin action. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2008;33:946–956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kanat M, Norton L, Winnier D, Jenkinson C, DeFronzo RA, Abdul-Ghani MA. Impaired early- but not late-phase insulin secretion in subjects with impaired fasting glucose. Acta Diabetol. 2012;48:209–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]