Abstract

The ability of cells to respond to changes in nutrient availability is essential for the maintenance of metabolic homeostasis and viability. One of the key cellular responses to nutrient withdrawal is the upregulation of autophagy. Recently, there has been a rapid expansion in our knowledge of the molecular mechanisms involved in the regulation of mammalian autophagy induction in response to depletion of key nutrients. Intracellular amino acids, ATP, and oxygen levels are intimately tied to the cellular balance of anabolic and catabolic processes. Signaling from key nutrient-sensitive kinases mTORC1 and AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) is essential for the nutrient sensing of the autophagy pathway. Recent advances have shown that the nutrient status of the cell is largely passed on to the autophagic machinery through the coordinated regulation of the ULK and VPS34 kinase complexes. Identification of extensive crosstalk and feedback loops converging on the regulation of ULK and VPS34 can be attributed to the importance of these kinases in autophagy induction and maintaining cellular homeostasis.

Keywords: autophagy, ULK1, AMPK, VPS34, amino acids, oxygen, mTORC1

Introduction

Macroautophagy, referred to hereafter simply as autophagy, is the primary catabolic program activated by cellular stressors including nutrient and energy starvation1. Autophagy begins by the de novo production of the autophagosome, a double membraned vesicle that expands to engulf neighbouring cytoplasmic components and organelles2. Autophagosome formation is driven by the concerted action of a suite of proteins designated as ATG or 'autophagy-related' proteins3. The mature autophagosome then becomes acidified after fusion with the lysosome, forming the autolysosome3. Lysosome fusion with the autophagosome provides luminal acid hydrolases that degrade the captured proteins, lipids, carbohydrates, nucleic acids, and organelles to provide nutrients that are then secreted back into the cytoplasm by lysosomal permeases for the cell's use under stress conditions. Autophagy can also be induced by damaged organelles, protein aggregates, and infected pathogens to maintain cell integrity or exert defense response. This review will primarily focus on recent advances in the mechanisms regulating autophagy in response to nutrients (amino acids, glucose, and oxygen).

The core autophagy proteins

In order to explain autophagy regulation, we will first describe the autophagy machinery in this section. ATG proteins are often listed in six functional groups that cooperate to perform key processes in autophagosome formation3: first, UNC-51-like kinase 1 (ULK1, a yeast Atg1 homolog) kinase complex comprised of ULK1, FIP200 (also known as RB1CC1), ATG13L, and ATG1014,5,6,7,8,9; second, the VPS34 kinase complex (a class III phosphatidylinositol (PtdIns) 3-kinase) comprised of VPS34 (also known as PIK3C3), VPS15 (also known as PIK3R4), Beclin-1, and ATG14 or UVRAG (these proteins bind Beclin-1 mutually exclusively)10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21; third, PtdIns 3-phosphate (PtdIns(3)P) binding proteins including WD-repeat-interacting phosphoinositide proteins and zinc finger FYVE domain-containing protein 1 (also known as DFCP1)22,23,24,25; fourth, the ATG5-12 ubiquitin-like conjugation system including the E3-ligase-like complex comprised of ATG12-ATG5-ATG16L (in which there is an isopeptide bond between ATG12 and ATG5)26,27; fifth, the microtubule-associated protein 1-light chain 3 (LC3) phosphatidylethanolamine conjugation system (in which phosphatidylethanolamine is conjugated to LC3 by the ATG12-ATG5-ATG16L complex)27,28; and sixth, ATG9a (a multi-spanning transmembrane protein), the only transmembrane protein among the ATG proteins29. The last group also includes the transmembrane protein vacuole membrane protein 1, which is not an ATG protein but is required for autophagy in mammals30,31. The ATG proteins in this list have been ranked hierarchically and temporally in mammals30,31.

Autophagy and the ubiquitin-proteasome system constitute the major degradative processes in the cell. While increasing evidence suggests that there is significant crosstalk between autophagy and the ubiquitin systems, we would like to highlight two important distinctions. First, autophagy generates energy in its degradation of macromolecules, while the proteasome system consumes ATP in the degradation process. Second, autophagy is virtually unlimited in the size of the hydrolysis targets (i.e., protein, lipid, carbohydrate, etc.) that it can break down. Accordingly, entire organelles, viruses, and large protein aggregates are selectively broken down by the autolysosome (reviewed in32,33,34). Because of these differences, autophagy is the degradative force upregulated in response to nutrient starvation, mitochondrial depolarization, pathogen infection, and toxic protein aggregates.

The requirement for autophagy in maintaining cellular nutrient homeostasis is dramatically seen in ATG5- or ATG7-null neonatal mouse. Born with little physical defects and in predicted Mendelian ratios, these autophagy-defective mice die within a 24-h period after birth35,36. Force-feeding can prolong survival, indicating a metabolic facet to the premature death. Analysis of key metabolites confirms that the autophagy-defective neonates suffer from a systemic amino acid deficiency and decreased glucose levels35,36. Interestingly, in cultured normal hepatocytes the rate of protein degradation increases by a stunning 3% of total protein/h upon starvation. Nearly all of this increase is attributed to autophagy35,37. Material recycling by autophagy is an evolutionally conserved mechanism required for the consumption of cytoplasmic ingredients under times of nutrient restriction35,36,38. Therefore, under periods of acute starvation, autophagy acts as an indispensible stress-responsive process capable of temporarily restoring cellular nutrient and energy balance.

Autophagy initiation

In mammals, the site of origin for autophagosome formation is the phagophore. The organelles that contribute lipids to the phagophore remain an active topic of debate and competing models are reviewed in detail elsewhere2. Currently, there is compelling evidence that the endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondrial interface plays an important role in the genesis of starvation-induced autophagosomes39,40, while a significant portion of autophagosomes have also been described as containing lipids from the Golgi and plasma membranes41,42,43. The recruitment of ATG proteins to the phagophore along with the acquisition of lipids expands the membrane to form a cup-shaped precursor of the autophagosome termed the omegasome44. The step-wise progression of autophagosome formation is largely characterized by the recruitment and detachment of autophagosomal proteins to the maturing organelle2,3,45.

ATG protein recruitment to the phagophore initiates autophagy

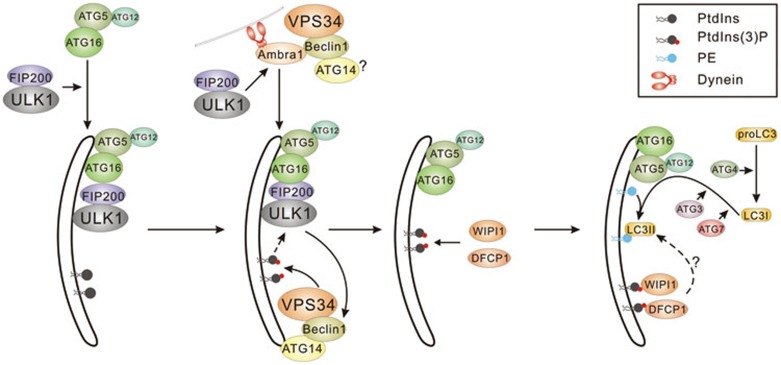

One of the earliest detectable events in autophagy initiation is the formation of ULK1 puntca30 (Figure 1). In mammals, ULK1 and ULK2 (hereafter ULK kinase will be used to refer to ULK1 and ULK2) are the only serine/threonine kinases in the dedicated autophagy machinery and are homologous to yeast ATG129,46. Genetic evidence suggests that ULK/ATG1 lies upstream of the recruitment of other ATG proteins30. The activity of ULK kinase is required for the recruitment of VPS34 to the phagophore30,31. VPS34 is the catalytic component of multiple protein complexes, some of which are implicated in autophagy-independent mechanisms, while others function in distinct stages of autophagy. Of these complexes, VPS34 complex containing VPS15, Beclin-1, and ATG14 is specifically recruited to the phagophore to phosphorylate PtdIns, producing PtdIns(3)P (Figure 1)15,20,30,31. PtdIns(3)P is essential for recruitment of a class of phospholipid-binding proteins whose exact functions in autophagy initiation remain enigmatic; however, in mammals and yeast they have been shown to play a role in autophagy22,23,25,30. Additionally, the production of PtdIns(3)P has recently been shown to stabilize ULK1 at the omegasome47. The recruitment of oligimers of ATG12-conguated ATG5 bound to ATG16L also coincides with ULK1 puntca formation48,49. The formation of the ATG12-ATG5-ATG16L complex requires the ubiquitin-like conjugation system involving ATG7 and ATG10 (reviewed in50) and optimal ULK1 puncta formation upon amino-acid withdrawal requires the direct binding of FIP200 to ATG16L (Figure 1)48,49. Functionally, ATG12-5-ATG16L is required for the conjugation of LC3 to phosphatidylethanolamine28. LC3B is a mammalian homolog of yeast ATG8, and is the most important and best characterized LC3 paralog from the family containing LC3 A, B, C for the induction of autophagy28,51. The conjugation of LC3-phosphatidylethanolamine is thought to be required for the closure of the expanding autophagosomal membrane52 (Figure 1). Finally, the phagophore contains two transmembrane proteins ATG9 and vacuole membrane protein 1 that are required for generation of the autophagosome and they retain punctate localization under nutrient-rich conditions30,53.

Figure 1.

ATG protein recruitment in mammalian autophagosome formation. Temporal and functional relationship between ATG-protein complexes in autophagosome formation is depicted. These relationships were assembled from multiple independent studies to generate a working model with details summarized in the text. The core of VPS34 complexes, containing VPS34 and VPS15, is depicted as VPS34.

The formation of the phagophore instigated by recruitment of ATG proteins is potently increased by withdrawal of nutrients, such as amino acids and glucose, so it is perhaps unsurprising that the kinases that sense these metabolites have recently been described to regulate autophagy initiation in response to changing energy and nutrient levels.

Amino acid signaling to mTORC1

The knowledge that autophagy is responsive to fluctuations in amino acids predates the identification and cloning of the ATG genes. In 1977, Schworer and colleagues showed that perfusion of rat livers in the absence of amino acids rapidly induced autophagosome number54. It was subsequently shown that branched chain-amino acids, in particular leucine, were responsible for the repression of protein turnover and autophagy55,56. One of the key downstream effectors of amino acid-mediated autophagy repression is mammalian target of rapamycin or mechanistic TOR (mTOR)57,58.

mTOR is a highly conserved serine/threonine kinase that is capable of integrating signals from many stimuli including amino acids, energy levels, oxygen, growth factors, and stress to coordinate cell growth and maintain metabolic homeostasis59. mTOR forms two functionally distinct complexes in mammals, mTORC1 (mTOR complex 1) and mTORC2 (mTOR complex 2). It is mTORC1 that is sensitive to both growth factors and nutrients, and the presence of amino acids has been shown to be essential for activation of the mTORC1 kinase60. Proteins including Ste-20-related kinase MAP4K3 and VPS34 have been described to play a role in amino acid signaling possibly through regulation of phosphatases and endocytic trafficking upstream of mTORC112,61,62,63,64. Nevertheless, the clearest mechanism for mTORC1 activation by amino acids came from identification of the Rag GTPase complexes that tether mTORC1 to the lysosome65,66 (Figure 2). The Rag family proteins are members of the Ras family of GTPases, comprised of four members (RagA-D) that form heterodimers. A Rag dimer, comprised of an A/B subunit with a C/D subunit, binds mTORC1 in the presence of amino acids at the lysosome65,66. Amino acid stimulation promotes Rag activation where Rag A/B is GTP-bound and Rag C/D is GDP-bound. Rag complexes are themselves not membrane-bound but are tethered to the lysosome through a complex called the Ragulator complex, which recruits Rag to lysosome and also functions as a guanine nucleotide exchange factor to stimulate Rag activation in response to amino acid sufficiency67 (Figure 2). The recruitment of mTORC1 to the lysosome brings it into proximity with another small GTPase Rheb that is absolutely required for mTORC1 activation68,69,70. Rheb itself is negatively regulated by the tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC1/2), which acts as a GTPase activating protein for Rheb68,70,71,72,73,74 (Figure 2). In the presence of growth factors, the TSC complex is inactivated by the PI3K pathway through multiple mechanisms including direct repression of TSC by AKT-mediated (alternatively referred to as protein kinase B) phosphorylation72,75 (Figure 2). Therefore, full activation of mTORC1 can only be achieved in the presence of both amino acids and growth factors.

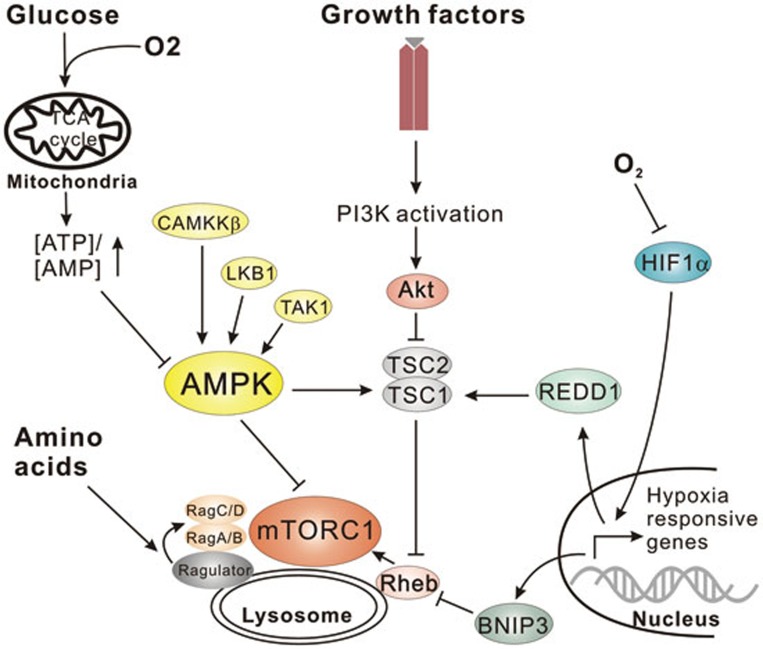

Figure 2.

Upstream nutrient signaling to mTORC1 and AMPK. Nutrient starvation results in the inactivation of mTORC1. Oxygen or nutrient deficiency can activate AMPK through ADP:AMP accumulation, negatively regulating mTORC1 through either AMPK-mediated phosphorylation of mTORC1 or activation of the upstream repressor TSC. Limited oxygen also upregulates hypoxia-responsive genes, which are capable of suppressing mTORC1 signaling through the activation of TSC or inhibition of Rheb. Amino-acid withdrawal or inactivation of the PI3K pathway inhibits mTORC1 signaling through negatively regulating the activation of mTORC1 at the lysosome by Rag GTPases and Rheb.

Downstream targets of mTORC1 in autophagy

mTORC1 is established as a potent repressor of autophagy in eukaryotes (TORC1 in yeast). Importantly, inhibition of mTORC1 is sufficient to induce autophagy in the presence of nutrients in yeast or mammalian cells76,77,78, establishing mTORC1 as a conserved and critical repressor of autophagy. Direct repression of ATG1/ULK1 kinase by TORC1 is conserved across eukaryotes; however, the mechanisms of repression differ considerably. In mammalian cells, the ULK-ATG13L-FIP200 trimeric complex is stable regardless of the nutrient status1. mTORC1 can interact with the ULK1 kinase complex and directly phosphorylates the ATG13L and ULK1 subunits to repress ULK1 kinase activity, although most sites have not been mapped or characterized6,7,8 (Figure 3). Recently, mTORC1 was shown to phosphorylate Ser757 on ULK1, a site now verified by multiple groups79,80,81,82. Phosphorylation of Ser757 is important for mTORC1 to repress autophagy induction. When mTORC1 is inhibited, ULK1 undergoes autophosphorylation and trans-phosphorylation of binding partners ATG13L and FIP200, leading to an activation of the kinase complex under starvation conditions.

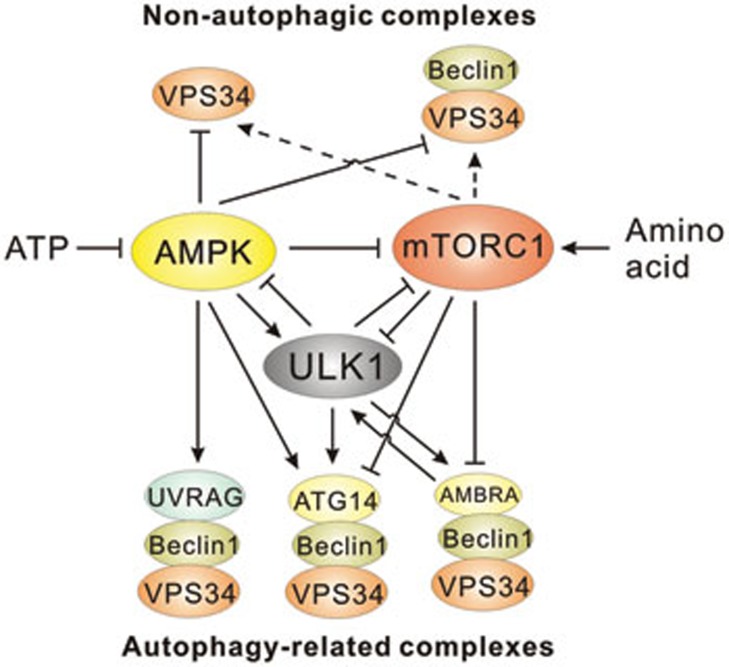

Figure 3.

Regulation of ULK1 and VPS34 complexes by nutrients and upstream kinases. Nutrient starvation activates ULK1 through AMPK-mediated phosphorylation or loss of mTORC1-mediated repression. Activation of ULK1 has been described to initiate a positive-feedback loop through the phosphorylation of the mTORC1 complex and a negative-feedback loop through the phosphorylation of AMPK. Activities of the core VPS34 complexes, containing VPS34 and VPS15 (depicted as VPS34 in all complexes), and Beclin-1-bound VPS34 are inhibited under starvation. AMPK-mediated repression of these complexes is caused by direct phosphorylation of the VPS34 catalytic subunit. Amino acid-induced activation of these complexes is mTORC1-dependent but not direct and does not involve ULK1 kinase. ATG14-containing VPS34 complexes are activated by AMPK or ULK1 through phosphorylation of Beclin-1 or can be inhibited by mTORC1-mediated phosphorylation of ATG14. UVRAG-containing VPS34 complexes are activated by AMPK-mediated phosphorylation of Beclin-1 in response to starvation. ULK1 phosphorylates AMBRA1, freeing VPS34 from the cytoskeleton to act at the phagophore. AMBRA1 acts in a positive-feedback loop with TRAF6 to promote ULK1 activation.

ULK regulation by mTORC1 in response to nutrients is functionally conserved across eukaryotes. Treatment of S. cerevisiae with rapamycin is sufficient to induce autophagy in the presence of nutrients83. TORC1-mediated repression of autophagy in yeast is accomplished through regulation of the ATG1 (homologue of mammalian ULK) kinase complex83. While the functional repression of ATG1 kinase complex by TORC1 is conserved, the proposed mechanisms differ considerably. In yeast, ATG1 forms an active kinase complex through an interaction with ATG13 and ATG17 (a functional homologue of mammalian FIP200)3,4. Under times of nutrient sufficiency, TORC1 phosphorylates ATG13 on multiple sites thereby preventing its association with ATG183,84,85. TORC1 inhibition by nutrient starvation or rapamycin treatment relieves the repression of ATG13 allowing the formation of an active ATG1-ATG13-ATG17 complex and induction of autophagy. However, it has recently been proposed that stability of the trimeric ATG1 kinase complex is not regulated by TORC1 or nutrient status in yeast, raising the possibility of alternative mechanism(s) in the regulation of the yeast ATG1 complex86. In mammalian cells, mTORC1 does not appear to regulate the formation of the ULK kinase complex79. Thus, TORC1-mediated phosphorylation of ATG13 is proposed to inhibit ATG1 kinase activity via phosphorylation of the kinase complex, as it does in fly and mammals5,6,7,8,87,88. Moreover, mTORC1 also inhibits ULK1 activation by phosphorylating ULK and interfering with its interaction with the upstream activating kinase AMPK79.

In yeast, ATG1 has been proposed to be downstream of Snf1 (AMPK homologue); however, the underlying mechanism remains to be determined89. Curiously, the yeast TORC1 has been described to inhibit Snf1, which is opposite to the AMPK-mediated repression of mTORC1 seen in mammals90. Together, these studies indicate that autophagy induction in eukaryotes is intimately tied to cellular energy status and nutrient availability through the direct regulation of the ATG1/ULK kinase complex by TORC1 and AMPK.

Interestingly, another facet of mTORC1-mediated autophagy repression has recently emerged. Under nutrient sufficiency, mTORC1 directly phosphorylates and inhibits ATG14-containing VPS34 complexes through its ATG14 subunit91 (Figure 3). Upon withdrawal of amino acids, ATG14-containing VPS34 complexes are dramatically activated. Abrogation of the 5 identified mTORC1 phosphorylation sites (Ser3, Ser223, Thr233, Ser383, and Ser440) resulted in an increased activity of ATG14-containing VPS34 kinase under nutrient rich conditions, although not to the same level as nutrient starvation91. Stable reconstitution with a mutant ATG14 resistant to mTORC1-mediated phosphorylation also increased autophagy under nutrient rich conditions91. The mTORC1-mediated direct repression of both ULK1 and pro-autophagic VPS34 complexes provides important mechanistic insights into how intracellular amino acids repress the initiation of mammalian autophagy.

mTORC1 also indirectly regulates autophagy by controlling lysosome biogenesis through direct regulation of transcription factor EB (TFEB)92,93. TFEB is responsible for driving the transcription of several lysosomal and autophagy-specific genes. mTORC1 and TFEB colocalize to the lysosomal membrane where mTORC1-mediated TFEB phosphorylation promotes YWHA (a 14-3-3 family member) binding to TFEB, leading to its cytoplasmic sequestration92. Under amino-acid withdrawal or inactivation of amino acid secretion from the lysosome, mTORC1 is inactivated and the unphosphorylated TFEB translocates to the nucleus. Artificial activation of mTORC1 by transfection of constitutively active Rag GTPase mutants results in a constitutive localization of TFEB in the cytoplasm and deletion of TFEB results in a decreased autophagy response to nutrient withdrawal and reduction in the cellular lysosome compartment93. Through the repression of TFEB, ULK kinase complexes, and VPS34-kinase complexes, mTORC1 is able to negatively regulate both the initiation and maturation of the autophagosome.

Paradoxically, under prolonged starvation the role of mTORC1 in autophagy flips from a repressor to a promoter of autophagy94. Under times of severe nutrient deprivation, autophagy is rapidly induced and a large portion of cellular lysosomes are used to form autolysosomes. The restoration of a normal compliment of lysosomes requires recycling of the autolysosomal membrane. For membrane recycling to occur, mTORC1 must be activated by the secreted amino acids from the mature autolysosome, which allows for the formation of an empty tubule that protrudes from the autolysosome94. These tubules eventually mature into lysosomes, restoring cellular lysosome numbers. The multiple levels at which mTORC1 can regulate and be regulated by autophagy are uniquely illustrated in the lysosomal storage disease mucolipidosis type IV (MLIV) where mTORC1 reactivation by the mature autolysosome is inhibited (see Box 1).

Box1 mTOR signaling and autophagy in MLIV.

MLIV is caused by a deficiency in the cation channel encoded by MCOLN1. MCOLN1 is required for the fusion of autophagosomes to lysosomes. When MCOLN1 function is disrupted, there is a buildup of autophagosomes that are bound to lysosomes but unable to fuse95,96. The resulting defect in autophagic flux causes decreased mTORC1 activity, which in turn causes a de-repression of lysosomal biogenesis, with TFEB likely playing a role. The end result is a drastic increase in acidic vesicles and defective autolysosome precursors. Remarkably, in the Drosophila model of MLIV, activation of Drosophilia TORC1 by introduction of a protein-rich diet was sufficient to reverse the MLIV phenotype97. This study shows that not only is Drosophilia TORC1 involved in the pathology of MLIV, but also that amino acids generated by autophagy are an important source for Drosophilia TORC1 activation.

Recent studies have greatly advanced our understanding of the complex crosstalk between autophagy and mTORC1 signaling, and it will be exciting to see what new connections will be uncovered between these two key processes in maintaining nutrient/energy homeostasis.

Energetic stress and AMPK signaling

In order to maintain metabolic homeostasis, the cell must strictly match the generation and consumption of ATP. The intracellular ratio of ATP:ADP:AMP is an important indicator of cellular energy levels. Increased levels of ADP and AMP signal to the cell that it must curtail energy-intensive processes. These nucleotides are directly sensed by the AMPK. AMPK is a trimeric serine/threonine kinase essential for an appropriate response to energetic stress (reviewed in98). The catalytic α subunit of AMPK is phosphorylated by upstream regulatory kinases LKB1, calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase-β, and TAK199,100,101 (Figure 2). Phosphorylation of AMPKα within the activation loop (T172) by upstream kinases is required for activity102,103,104. The β subunit acts as a linker between α and γ subunits and may have additional regulatory function(s), such as glycogen-binding. AMPK can be allosterically activated through the binding of AMP to one of four Bateman domains in the γ subunit, resulting in allosteric activation of the associated α subunit. More importantly, AMP and ADP activate AMPK by preventing dephosphorylation of T172 in the AMPK α subunit105,106,107. The binding of ADP does not elicit allosteric activation but does promote stabilization of the activation loop102,108. Reduction in cellular ATP levels, caused by glucose withdrawal or other stressors such as mitochondrial dysfunction initiates a cellular metabolic response through AMPK targets that seek to generate energy by increasing glucose uptake and glycolysis and stimulating lipid catabolism (for detailed review, see109).

Downstream targets of AMPK in autophagy

Activation of autophagy in response to energetic stress is an essential mechanism to maintain metabolic homeostasis and cell viability. AMPK has recently been shown to be an essential mediator of autophagy induction in response to glucose withdrawal and essential for cytoprotection under these conditions79,110. There are several mechanisms by which AMPK can promote autophagy. Importantly, AMPK is an established negative regulator of the mTOR signaling cascade74,111. This can be accomplished by AMPK-mediated phosphorylation of the TSC complex which is a negative regulator of mTORC1 activation at the lysosome (Figure 2). Alternatively, AMPK can directly phosphorylate the Raptor subunit of the mTORC1 complex, which induces 14-3-3 binding and inhibits mTORC1 target phosphorylation112 (Figure 2). Through both these mechanisms, AMPK is able to relieve mTOR-mediated autophagy repression.

AMPK is also capable of directly phosphorylating and activating ULK1 kinase79,113. Work from our lab found that Ser317 and Ser777 (in the mouse ULK1 protein) phosphorylation of ULK1 by AMPK is required for ULK1 activation and proper induction of autophagy upon glucose starvation79 (Figure 3). Moreover, the interaction between ULK1 and AMPK was antagonized by mTORC1-mediated Ser757 phosphorylation of ULK1, indicating a tight control of ULK1 activity in response to nutrient and energy levels. Several additional phosphorylation sites were found (Ser467, Ser556, Thr575, and Ser638) to be important for mitophagy110 and Ser556 phosphorylation was shown to be required for 14-3-3 binding to ULK1113. Interestingly, another study also found many overlapping AMPK and mTORC1-dependent phosphorylation events on ULK1 with some details conflicting with previous reports, possibly due to different starvation conditions used in these reports81. In total, these studies clearly demonstrate that AMPK and mTORC1 both tightly control ULK1 function through protein phosphorylation.

AMPK has also recently been shown to regulate multiple VPS34 complexes upon glucose withdrawal. Under starvation, AMPK inhibits VPS34 complexes that do not contain pro-autophagic adaptors, such as UVRAG and ATG14 (see Beclin-1 binding partners in Table 1). These VPS34 complexes are not involved in autophagy but rather are involved in cellular vesicle trafficking. Inhibition was shown to be mediated through direct phosphorylation of VPS34 on Thr163 and Ser165 by AMPK114 (Figure 3). Concomitantly, AMPK enhances VPS34 kinase activity in complexes containing UVRAG or ATG14 by phosphorylation of Beclin-1 on Ser91 and Ser94 (Figure 3). The ATG14- or UVRAG-containing VPS34 complexes are involved in autophagy initiation. Activation of ATG14-containing VPS34 complexes through Beclin-1 phosphorylation was shown to be required for the induction of autophagy upon glucose withdrawal114. Interestingly, inhibitory phosphorylation of VPS34 was shown to be important for survival in response to glucose withdrawal; however, it did not affect autophagy induction. Further studies will be required to shed light on how repression of total PtdIns(3)P levels promotes survival under energetic stress.

Table 1. Beclin-1 interacting proteins implicated in starvation-induced autophagy.

| Protein | Interaction and function | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Positive regulators of autophagy | ||

| VPS34 | catalytic subunit of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase complexes | 11,155 |

| VPS15 | cofactor of VPS34 required for production of PtdIns(3)P | 17,151 |

| UVRAG | promotes autophagy, present in late endosomes | 11,21,156 |

| ATG14 | promotes autophagy, essential for localization of VPS34 to phagophore | 11,21 |

| AMBRA1 | promotes autophagy, nutrient-dependent localization of Beclin-1 | 131,157 |

| HMGB1 | promotes autophagy, increases VPS34 activity | 158 |

| Bif-1 | promotes autophagy, promotes UVRAG-containing VPS34 complexes | 159 |

| Negative regulators of autophagy | ||

| Rubicon | inhibits autophagy, antagonizes UVRAG-containing VPS34 complexes | 16,19 |

| Bcl-2 | inhibits autophagy, inhibits Beclin-1-containing VPS34 complexes | 142 |

| Bcl-xL | inhibits autophagy, binds Beclin-1 complexes at the ER | 145 |

| IP3R | inhibits autophagy, binds Beclin-1 complexes at the ER | 160 |

Oxygen availability

Oxygen is an essential nutrient that is required for key metabolic processes within the cell. Perhaps one of the most important functions of molecular oxygen within the cell is in oxidative respiration. Oxygen along with the electron transport chain in the mitochondria is necessary for generating ATP through oxidative phosphorylation115. Hypoxia results in a reduction in ATP levels, at least transiently, which activates AMPK and inactivates mTOR116,117,118 (Figure 2). The activation of AMPK and inactivation of mTOR are adaptive responses as the cell shifts its metabolic priorities, producing energy in other ways such as increased glycolysis as well as reducing energy-consuming processes.

One of the best-characterized events of the hypoxic response is stabilization of the HIF1α transcription factor115,119. In the absence of oxygen, HIF1α escapes proteasomal degradation by the von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor and accumulates in the nucleus where it activates the transcription of a wide array of genes that are necessary for metabolic adaptation to reduced oxygen levels120. Two hypoxia responsive genes, BNIP3 and BNIP3L, aid in balancing ATP consumption by increasing mitochondrial autophagy under low oxygen conditions121. Moreover, BNIP3 has been described to negatively regulate mTORC1 activation possibly through binding of the small GTPase Rheb122 (Figure 2). Interestingly, another hypoxia responsive gene REDD1 has also been implicated in negatively regulating mTORC1 through activation of the TSC complex123,124,125 (Figure 2). Additionally, some HIF-responsive genes have been described to affect VPS34 complex formation (discussed below). Together these studies show that oxygen depletion in the cell is intimately tied to the upstream regulation of autophagy by AMPK and mTORC1.

The autophagy initiating kinase ULK

ULK is the most upstream ATG protein regulating autophagy initiation in response to inductive signals. ULK1 was identified as the mammalian homolog of Caenorhabditis elegans Unc-51, which was originally characterized as being essential for neuronal axon guidance126. In mammals, the ULK1-knockout mouse has a very mild phenotype showing defects in reticulocyte development and mitochondrial clearance in these cells127. This is likely due to the functional redundancy with ULK2 that has been described for autophagy induction128,129. ULK directly interacts with ATG13L and FIP200 through the C-terminal domain and both interactions can stabilize and activate ULK-kinase5,6,7,8. The ULK-kinase complex is under tight regulation in response to nutrients, energy, and growth factors as described in previous sections. The original phospho-mapping of murine ULK1 identified 16 phosphorylation sites, although the kinases responsible for several of these phosphorylation events remain unknown80. Additional studies have increased the number of phosphorylation sites to over 40 residues on ULK1 including a critical site on the activation loop T180, that is required for autophosphorylation113. In addition to autophosphorylation, ULK can phosphorylate both ATG13L and FIP200, and the intact kinase complex is required for ULK localization to the phagophore and autophagy induction4,5,6,8.

Downstream targets of ULK

Despite ULK's pivotal role in conveying nutrient signal to the autophagy cascade, the mechanisms and downstream targets responsible were until recently enigmatic. Three direct targets of ULK1 have recently been identified as well as two feedback loops to mTORC1 and AMPK. Recent work from our lab found that ULK1 and ULK2 directly phosphorylate Beclin-1 on S15 (murine S14) and this phosphorylation is required for activation of ATG14-containing VPS34 complexes130 (Figure 3). The ability of Beclin-1 and ULK1 to bind in vivo was promoted by ATG14, which was proposed to act as an adaptor in Beclin-1 binding to ULK. Interestingly, the ability of ATG14 to promote Beclin-1 phosphorylation was abolished in mutants that could not localize to the phagophore, indicating that the activation of ATG14-containing VPS34 complexes may occur specifically at the phagophore (Figure 1). The conserved phosphorylation site on Beclin-1 was shown to be required for proper induction of autophagy in mammals and autophagy during C. elegans embryogenesis130.

A Beclin-1 binding partner, activating molecule in Beclin1-regulated autophagy 1 (AMBRA1), has also been identified as a target for ULK1-mediated phosphorylation131 (Figure 3). Under nutrient-rich conditions, AMBRA1 binds Beclin-1 and VPS34 at the cytoskeleton through an interaction with dynein. Upon starvation, ULK1 phosphorylates AMBRA1, and Beclin-1 then translocates to the endoplasmic reticulum, allowing VPS34 to act at the phagophore131 (Figure 1). This model is in agreement with previous findings that ATG14-containing VPS34 complexes require ULK-kinase to localize to the phagophore15,20,30. However, it is currently unclear if Beclin-1 binds ATG14 and AMBRA1 in the same complex at the site of the phagophore. Interestingly, AMBRA1 was shown to act in an mTORC1-sensitive positive-feedback loop to promote K63-linked ubiquitination of ULK1 through recruitment of the E3-ubiquitin ligase TRAF6132 (Figure 3).

ULK1 has also been described to phosphorylate zipper interacting protein kinase, also known as DAPK3133. It was reported that ULK-induced zipper interacting protein kinase phosphorylation plays a role in the re-distribution of the transmembrane protein ATG9a from the transgolgi network to peripheral endosomes that are capable of being incorporated into the autophagosome133, which has been described to be nutrient sensitive5,29. However, it was recently reported by multiple groups that the localization of ATG9a to the autophagosomal membrane is ULK-independent and that it was the recycling of ATG9a that is ULK-sensitive53,134. In an alternative ULK-independent model, ATG9a is bound and inhibited by p38-interacting protein and then released after starvation-induced phosphorylation of p38-interacting protein by MAPK p38135. However, ULK clearly regulates some ATG9a-related processes29,133,136. Additional studies will be needed to clarify the role of zipper interacting protein kinase and ULK kinase in ATG9a localization to the autophagosomal membrane.

ULK1 feedback loops

ULK1 has recently been described to initiate two feedback loops. Two groups have independently identified ULK1 as a negative regulator of mTORC1-signaling through phosphorylation of the raptor subunit137,138. The proposed model is that ULK-mediated phosphorylation of raptor results in a reduction in the ability of mTORC1 to bind substrate. This would represent a positive-feedback loop that may be important for ramping up the signaling in the earlier stages of autophagy, while amino acids that are secreted from the autolysosome would then re-activate mTOR in later stages of autophagy. ULK1 was also described to bind and phosphorylate its upstream regulator AMPK on all three subunits, though surprisingly this regulation was also inhibitory139. This would represent a negative-feedback loop in response to AMPK-mediated ULK activation. Clearly, there are several interdependencies between AMPK-mTOR-ULK kinases, some of which may seem counterintuitive in regulating the activation of autophagy in response to nutrient stress. It is possible that under the fluctuations of nutrient/energy levels that occur physiologically in vivo some of these signals may act dichotomously. Alternatively, different feedback loops could be activated under different stress conditions or act temporally.

Regulation of VPS34-kinase complexes in response to nutrients

Generation of PtdIns(3)P at the phagophore is necessary for the expansion of the membrane. Production of PtdIns(3)P at the phagophore is controlled by at least three known mechanisms: (1) localization of the VPS34 kinase complex, regulated by Beclin-1:ATG14/AMBRA binding and controlled by ULK-kinase activity16,19,20,21,30,131; (2) activation of VPS34 kinase activity, controlled by ULK1, mTOR, and AMPK in response to nutrients91,114,130 (activity is also affected by binding to Beclin-1 and ATG14114); and (3) regulation of VPS34 complex formation through the Beclin-1 interactome140,141,142.

The core VPS34 complex that is comprised of VPS34 and the regulator VPS15 likely does not directly act in promoting autophagosome formation114. VPS34-VPS15 complexes are likely the predominant form in the cell as quantitative immuno-depletion revealed that the majority of VPS34-VPS15 is not bound to Beclin-1, although the relative abundance of different VPS34 complexes is cell type-dependent114. VPS34 complexes that have a role in promoting autophagy contain Beclin-1142. However, it appears that for VPS34 to produce PtdIns(3)P at the correct site and stage of autophagy, additional components are needed. Beclin-1 acts as an adaptor for pro-autophagic VPS34 complexes to recruit additional regulatory subunits such as ATG14 and UVRAG11,15,16,19,20,21. ATG14 or UVRAG binding to the VPS34 complex potently increases the PI3 kinase activity of VPS34. Moreover, the dynamics of VPS34-Beclin-1 interaction has been described to regulate autophagy in a nutrient-sensitive manner140,142,143. A list of Beclin-1 interactors with known functions has been summarized (see Table 1); however, this section will focus on changes in VPS34 complex composition that are sensitive to alteration of nutrients.

The ability of VPS34 complexes containing Beclin-1 to promote autophagy can be negatively regulated by Bcl-2 as well as family members Bcl-xl and viral Bcl-2142,144,145,146. Bcl-2 binding to the BH3 domain in Beclin-1 at the endoplasmic reticulum and not the mitochondria seems to be important for the negative regulation of autophagy, and Bcl-2-mediated repression of autophagy has been described in several studies140,142,143,145,147,148. The nutrient-deprivation autophagy factor-1) was identified as a Bcl-2 binding partner that specifically binds Bcl-2 at the ER to antagonize starvation-induced autophagy149. There are two proposed models for the ability of Bcl-2 to inhibit VPS34 activity. In the predominant model, Bcl-2 binding to Beclin-1 disrupts VPS34-Beclin-1 interaction resulting in the inhibition of autophagy140,142 (Figure 4). Alternatively, Bcl-2 has been proposed to inhibit pro-autophagic VPS34 through the stabilization of dimerized Beclin-114,150 (Figure 4). It remains to be seen if the switch from Beclin-1 homo-dimers to UVRAG/ATG14-containing heterodimers is a physiologically relevant mode of VPS34 regulation. Given the number of studies that see stable interactions under starvation between VPS34 and Beclin-162,91,114,130,143,151 and those that see a disruption140,142, it is quite likely that multiple mechanisms exist to regulate VPS34 complexes containing Beclin-1. It may be noteworthy that studies that do not see changes in the VPS34-Beclin-1 interaction tend to use shorter time points (∼1 h amino acid starvation), while studies that see disruption tend to use longer time points (∼4 h). If the differences cannot be explained by media composition or cell type, it would be interesting to determine if Bcl-2 is inhibiting VPS34 through Beclin-1 dimerization at shorter time points, or if the negative regulation of VPS34-Beclin-1 complexes by Bcl-2 happens with a temporal delay upon nutrient deprivation.

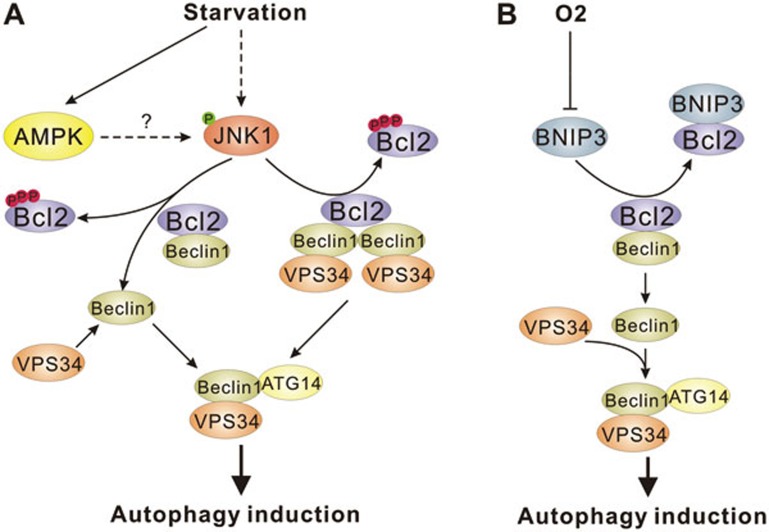

Figure 4.

Regulation of VPS34 complex formation in response to nutrients. (A) Starvation activates JNK1 kinase, possibly through direct phosphorylation by AMPK. JNK1 phosphorylates Bcl-2, relieving Bcl-2-mediated repression of Beclin-1-VPS34 complexes. Bcl-2 may inhibit VPS34 complexes by disrupting Beclin-1-VPS34 interaction (left arrow) or by stabilizing an inactive Beclin-1 homodimeric complex (right arrow). (B) Hypoxia upregulates BNIP3 expression, which can bind Bcl-2, thereby relieving Bcl-2-mediated repression of Beclin-1-VPS34 complexes.

The ability of Bcl-2 to bind Beclin-1 is also regulated by phosphorylation. Levine and colleagues have shown that starvation-induced autophagy requires c-Jun N-terminal protein kinase 1 (JNK1)-mediated phosphorylation of Bcl-2140. JNK1 but not JNK2 phosphorylates Bcl-2 on three residues (Thr69, Ser70, and Ser87) resulting in the dissociation of Bcl-2 from Beclin-1 (Figure 4). Interestingly, mutants of Bcl-2 containing phospho-mimetic residues at JNK1 phosphorylation sites led to increased autophagy levels indicating that activation of JNK1 is essential for relieving Bcl-2-mediated suppression of autophagy140. A potential mechanism for JNK1 activation upon starvation has recently been proposed. He et al.143 showed that AMPK activation can promote JNK1 signaling to Bcl-2 and increase autophagy. Moreover, they showed that AMPK can phosphorylate JNK1 in vitro and AMPK-JNK1 interaction is increased in vivo upon AMPK activation by metformin (Figure 4A). However, this observation is very surprising because the activation loop sites in JNK do not fit the AMPK consensus and AMPK is not known to have tyrosine kinase activity. Further studies are needed to confirm a direct activation of JNK1 by AMPK. Nevertheless, this study presents a potential mechanism linking the decrease in cellular energy to the Bcl-2-mediated regulation of autophagy. Lowered oxygen level has also been described to disrupt the Bcl-2-Beclin-1 interaction. Under hypoxia, HIF1α target genes BNIP3 and BNIP3L have been described as having a role in driving autophagy by displacing Bcl-2 from Beclin-1152,153. The BH3 domain of BNIP3 was described to bind and sequester Bcl-2, thus relieving its inhibition of Beclin-1 (Figure 4B). Taken together, these studies clearly indicate an inhibitory role for Bcl-2 on Beclin-1 in autophagy. It is quite likely that additional insights into this regulatory mechanism will be forthcoming.

Our understanding of the mechanisms regulating VPS34 complexes in response to nutrient deprivation has rapidly advanced in recent years. However, the identification of parallel pathways, such as ULK- and AMPK-mediated activation of ATG14-containing VPS34 complexes, has also raised questions of which regulatory pathways are relevant in response to different starvation stimuli (i.e., glucose vs amino-acid withdrawal) and whether there is crosstalk between the regulatory pathways that converge upon VPS34 complexes. Answering these questions will undoubtedly shed light on nuances of autophagy induction in mammals that have previously been unappreciated.

Conclusion

The ability of both mTORC1 and AMPK to regulate autophagy induction through ULK and VPS34 kinases has raised important questions. e.g., is there interplay between mTORC1- and AMPK-mediated phosphorylation of the ATG14-containing VPS34 complexes? The PI3K pathway has been described to regulate autophagy via mTORC1-dependent and independent mechanisms. The relationship between these two pathways in autophagy induction remains an open question. Moreover, characterization of signals that intersect to provide the cell-type specificity of autophagic induction in vivo has been described, but for the most part the underlying mechanisms remains to be revealed154.

The formation of ULK1 puncta is an early marker for autophagy induction. However, the mechanism regulating ULK1 translocation to the phagophore is poorly understood. The identity of membrane-bound ULK-receptors as well as upstream signals essential for regulating ULK localization remain unknown and are important outstanding questions. To date, only a handful of ULK targets have been identified and no consensus motif for the kinase has been described. The identification and characterization of additional ULK targets will undoubtedly shed light on the mechanisms of ULK-dependent autophagic processes that remain elusive.

As described above, the relationship between mTORC1-, AMPK-, and ULK-mediated regulation of the VPS34 complexes remains to be determined. Moreover, the regulation of VPS34 kinase activity by complex formation and phosphorylation is poorly understood and would benefit from studies providing structural insights. Additionally, the physiological significance of reducing total PtdIns(3)P levels under starvation is not entirely clear. It may be simply that running the endocytic pathway is an energy intensive endeavor, or perhaps membrane cycling or cell signaling from the endosomes is important in times of starvation. Finally, the exact role of PtdIns(3)P-binding proteins in promoting autophagy remains to be determined. Given the potential redundancy of these proteins, it remains a difficult question to tackle. Overall, the field has made great progress in understanding how nutrient information is transmitted to the autophagy pathway and like any good discovery, this has left us with as many questions as answers.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank our colleague Mr Steve Plouffe for critical reading of this manuscript. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants to KLG. RCR is supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) postdoctoral fellowship.

References

- Mizushima N, Klionsky DJ. Protein turnover via autophagy: implications for metabolism. Annu Rev Nutr. 2007;27:19–40. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.27.061406.093749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mari M, Tooze SA, Reggiori F. The puzzling origin of the autophagosomal membrane. F1000 Biol Rep. 2011;3:25. doi: 10.3410/B3-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizushima N, Yoshimori T, Ohsumi Y. The role of Atg proteins in autophagosome formation. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2011;27:107–132. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-092910-154005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara T, Takamura A, Kishi C, et al. FIP200, a ULK-interacting protein, is required for autophagosome formation in mammalian cells. J Cell Biol. 2008;181:497–510. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200712064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan EY, Longatti A, McKnight NC, Tooze SA. Kinase-inactivated ULK proteins inhibit autophagy via their conserved C-terminal domains using an Atg13-independent mechanism. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:157–171. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01082-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganley IG, Lam du H, Wang J, Ding X, Chen S, Jiang X. ULK1.ATG13.FIP200 complex mediates mTOR signaling and is essential for autophagy. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:12297–12305. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M900573200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosokawa N, Hara T, Kaizuka T, et al. Nutrient-dependent mTORC1 association with the ULK1-Atg13-FIP200 complex required for autophagy. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:1981–1991. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-12-1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung CH, Jun CB, Ro SH, et al. ULK-Atg13-FIP200 complexes mediate mTOR signaling to the autophagy machinery. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:1992–2003. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-12-1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosokawa N, Sasaki T, Iemura S, Natsume T, Hara T, Mizushima N. Atg101, a novel mammalian autophagy protein interacting with Atg13. Autophagy. 2009;5:973–979. doi: 10.4161/auto.5.7.9296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman PK, Emr SD. Characterization of VPS34, a gene required for vacuolar protein sorting and vacuole segregation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:6742–6754. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.12.6742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itakura E, Kishi C, Inoue K, Mizushima N. Beclin 1 forms two distinct phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase complexes with mammalian Atg14 and UVRAG. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:5360–5372. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-01-0080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juhász G, Hill JH, Yan Y, et al. The class III PI(3)K Vps34 promotes autophagy and endocytosis but not TOR signaling in Drosophila. J Cell Biol. 2008;181:655–666. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200712051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kihara A, Noda T, Ishihara N, Ohsumi Y. Two distinct Vps34 phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase complexes function in autophagy and carboxypeptidase Y sorting in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Cell Biol. 2001;152:519–530. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.3.519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, He L, Che KH, et al. Imperfect interface of Beclin1 coiled-coil domain regulates homodimer and heterodimer formation with Atg14L and UVRAG. Nat Commun. 2012;3:662. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsunaga K, Morita E, Saitoh T, et al. Autophagy requires endoplasmic reticulum targeting of the PI3-kinase complex via Atg14L. J Cell Biol. 2010;190:511–521. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200911141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsunaga K, Saitoh T, Tabata K, et al. Two Beclin 1-binding proteins, Atg14L and Rubicon, reciprocally regulate autophagy at different stages. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:385–396. doi: 10.1038/ncb1846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemazanyy I, Blaauw B, Paolini C, et al. Defects of Vps15 in skeletal muscles lead to autophagic vacuolar myopathy and lysosomal disease. EMBO Mol Med. 2013;5:870–890. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201202057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volinia S, Dhand R, Vanhaesebroeck B, et al. A human phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase complex related to the yeast Vps34p-Vps15p protein sorting system. EMBO J. 1995;14:3339–3348. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07340.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong Y, Wang QJ, Li X, et al. Distinct regulation of autophagic activity by Atg14L and Rubicon associated with Beclin 1-phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase complex. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:468–476. doi: 10.1038/ncb1854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan W, Nassiri A, Zhong Q. Autophagosome targeting and membrane curvature sensing by Barkor/Atg14(L) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:7769–7774. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016472108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Q, Fan W, Chen K, Ding X, Chen S, Zhong Q. Identification of Barkor as a mammalian autophagy-specific factor for Beclin 1 and class III phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:19211–19216. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810452105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polson HE, de Lartigue J, Rigden DJ, et al. Mammalian Atg18 (WIPI2) localizes to omegasome-anchored phagophores and positively regulates LC3 lipidation. Autophagy. 2010;6:506–522. doi: 10.4161/auto.6.4.11863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proikas-Cezanne T, Waddell S, Gaugel A, Frickey T, Lupas A, Nordheim A. WIPI-1alpha (WIPI49), a member of the novel 7-bladed WIPI protein family, is aberrantly expressed in human cancer and is linked to starvation-induced autophagy. Oncogene. 2004;23:9314–9325. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vergne I, Roberts E, Elmaoued RA, et al. Control of autophagy initiation by phosphoinositide 3-phosphatase Jumpy. EMBO J. 2009;28:2244–2258. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axe EL, Walker SA, Manifava M, et al. Autophagosome formation from membrane compartments enriched in phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate and dynamically connected to the endoplasmic reticulum. J Cell Biol. 2008;182:685–701. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200803137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizushima N, Sugita H, Yoshimori T, Ohsumi Y. A new protein conjugation system in human. The counterpart of the yeast Apg12p conjugation system essential for autophagy. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:33889–33892. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.51.33889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita N, Itoh T, Omori H, Fukuda M, Noda T, Yoshimori T. The Atg16L complex specifies the site of LC3 lipidation for membrane biogenesis in autophagy. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:2092–2100. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-12-1257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabeya Y, Mizushima N, Ueno T, et al. LC3, a mammalian homologue of yeast Apg8p, is localized in autophagosome membranes after processing. EMBO J. 2000;19:5720–5728. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.21.5720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young AR, Chan EY, Hu XW, et al. Starvation and ULK1-dependent cycling of mammalian Atg9 between the TGN and endosomes. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:3888–3900. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itakura E, Mizushima N. Characterization of autophagosome formation site by a hierarchical analysis of mammalian Atg proteins. Autophagy. 2010;6:764–776. doi: 10.4161/auto.6.6.12709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koyama-Honda I, Itakura E, Fujiwara TK, Mizushima N. Temporal analysis of recruitment of mammalian ATG proteins to the autophagosome formation site. Autophagy. 2013;9:1491–1499. doi: 10.4161/auto.25529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richetta C, Faure M. Autophagy in antiviral innate immunity. Cell Microbiol. 2013;15:368–376. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubli DA, Gustafsson AB. Mitochondria and mitophagy: the yin and yang of cell death control. Circ Res. 2012;111:1208–1221. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.265819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravikumar B, Sarkar S, Davies JE, et al. Regulation of mammalian autophagy in physiology and pathophysiology. Physiol Rev. 2010;90:1383–1435. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00030.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komatsu M, Waguri S, Ueno T, et al. Impairment of starvation-induced and constitutive autophagy in Atg7-deficient mice. J Cell Biol. 2005;169:425–434. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200412022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuma A, Hatano M, Matsui M, et al. The role of autophagy during the early neonatal starvation period. Nature. 2004;432:1032–1036. doi: 10.1038/nature03029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schworer CM, Shiffer KA, Mortimore GE. Quantitative relationship between autophagy and proteolysis during graded amino acid deprivation in perfused rat liver. J Biol Chem. 1981;256:7652–7658. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onodera J, Ohsumi Y. Autophagy is required for maintenance of amino acid levels and protein synthesis under nitrogen starvation. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:31582–31586. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506736200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamasaki M, Furuta N, Matsuda A, et al. Autophagosomes form at ER-mitochondria contact sites. Nature. 2013;495:389–393. doi: 10.1038/nature11910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hailey DW, Rambold AS, Satpute-Krishnan P, et al. Mitochondria supply membranes for autophagosome biogenesis during starvation. Cell. 2010;141:656–667. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravikumar B, Moreau K, Jahreiss L, Puri C, Rubinsztein DC. Plasma membrane contributes to the formation of pre-autophagosomal structures. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:747–757. doi: 10.1038/ncb2078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto A, Masaki R, Tashiro Y. Characterization of the isolation membranes and the limiting membranes of autophagosomes in rat hepatocytes by lectin cytochemistry. J Histochem Cytochem. 1990;38:573–580. doi: 10.1177/38.4.2319125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi-Nishino M, Fujita N, Noda T, Yamaguchi A, Yoshimori T, Yamamoto A. A subdomain of the endoplasmic reticulum forms a cradle for autophagosome formation. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:1433–1437. doi: 10.1038/ncb1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonsen A, Stenmark H. Self-eating from an ER-associated cup. J Cell Biol. 2008;182:621–622. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200807061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki K, Kubota Y, Sekito T, Ohsumi Y. Hierarchy of Atg proteins in pre-autophagosomal structure organization. Genes Cells. 2007;12:209–218. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2007.01050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan J, Kuroyanagi H, Kuroiwa A, et al. Identification of m0ouse ULK1, a novel protein kinase structurally related to C. elegans UNC-51. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;246:222–227. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karanasios E, Stapleton E, Manifava M, et al. Dynamic association of the ULK1 complex with omegasomes during autophagy induction. J Cell Sci. 2013;126(Pt 22):5224–5238. doi: 10.1242/jcs.132415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gammoh N, Florey O, Overholtzer M, Jiang X. Interaction between FIP200 and ATG16L1 distinguishes ULK1 complex-dependent and -independent autophagy. Nat Struc Mol Biol. 2013;20:144–149. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura T, Kaizuka T, Cadwell K, et al. FIP200 regulates targeting of Atg16L1 to the isolation membrane. EMBO Rep. 2013;14:284–291. doi: 10.1038/embor.2013.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geng J, Klionsky DJ. The Atg8 and Atg12 ubiquitin-like conjugation systems in macroautophagy. 'Protein modifications: beyond the usual suspects' review series. EMBO Rep. 2008;9:859–864. doi: 10.1038/embor.2008.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanida I, Tanida-Miyake E, Komatsu M, Ueno T, Kominami E. Human Apg3p/Aut1p homologue is an authentic E2 enzyme for multiple substrates, GATE-16, GABARAP, and MAP-LC3, and facilitates the conjugation of hApg12p to hApg5p. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:13739–13744. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200385200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita N, Hayashi-Nishino M, Fukumoto H, et al. An Atg4B mutant hampers the lipidation of LC3 paralogues and causes defects in autophagosome closure. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:4651–4659. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-03-0312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orsi A, Razi M, Dooley HC, et al. Dynamic and transient interactions of Atg9 with autophagosomes, but not membrane integration, are required for autophagy. Mol Biol Cell. 2012;23:1860–1873. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E11-09-0746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortimore GE, Schworer CM. Induction of autophagy by amino-acid deprivation in perfused rat liver. Nature. 1977;270:174–176. doi: 10.1038/270174a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li JB, Jefferson LS. Influence of amino acid availability on protein turnover in perfused skeletal muscle. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1978;544:351–359. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(78)90103-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seglen PO, Gordon PB, Poli A. Amino acid inhibition of the autophagic/lysosomal pathway of protein degradation in isolated rat hepatocytes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1980;630:103–118. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(80)90141-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blommaart EF, Luiken JJ, Blommaart PJ, van Woerkom GM, Meijer AJ. Phosphorylation of ribosomal protein S6 is inhibitory for autophagy in isolated rat hepatocytes. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:2320–2326. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.5.2320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwamaru A, Kondo Y, Iwado E, et al. Silencing mammalian target of rapamycin signaling by small interfering RNA enhances rapamycin-induced autophagy in malignant glioma cells. Oncogene. 2007;26:1840–1851. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laplante M, Sabatini DM. mTOR signaling in growth control and disease. Cell. 2012;149:274–293. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewell JL, Russell RC, Guan KL. Amino acid signalling upstream of mTOR. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2013;14:133–139. doi: 10.1038/nrm3522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan L, Mieulet V, Burgess D, et al. PP2A T61 epsilon is an inhibitor of MAP4K3 in nutrient signaling to mTOR. Mol Cell. 2010;37:633–642. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byfield MP, Murray JT, Backer JM. hVps34 is a nutrient-regulated lipid kinase required for activation of p70 S6 kinase. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:33076–33082. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507201200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nobukuni T, Joaquin M, Roccio M, et al. Amino acids mediate mTOR/raptor signaling through activation of class 3 phosphatidylinositol 3OH-kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:14238–14243. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506925102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Findlay GM, Yan L, Procter J, Mieulet V, Lamb RF. A MAP4 kinase related to Ste20 is a nutrient-sensitive regulator of mTOR signalling. Biochem J. 2007;403:13–20. doi: 10.1042/BJ20061881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim E, Goraksha-Hicks P, Li L, Neufeld TP, Guan KL. Regulation of TORC1 by Rag GTPases in nutrient response. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:935–945. doi: 10.1038/ncb1753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sancak Y, Peterson TR, Shaul YD, et al. The Rag GTPases bind raptor and mediate amino acid signaling to mTORC1. Science. 2008;320:1496–1501. doi: 10.1126/science.1157535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sancak Y, Bar-Peled L, Zoncu R, Markhard AL, Nada S, Sabatini DM. Ragulator-Rag complex targets mTORC1 to the lysosomal surface and is necessary for its activation by amino acids. Cell. 2010;141:290–303. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garami A, Zwartkruis FJ, Nobukuni T, et al. Insulin activation of Rheb, a mediator of mTOR/S6K/4E-BP signaling, is inhibited by TSC1 and 2. Mol Cell. 2003;11:1457–1466. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00220-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoki K, Li Y, Xu T, Guan KL. Rheb GTPase is a direct target of TSC2 GAP activity and regulates mTOR signaling. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1829–1834. doi: 10.1101/gad.1110003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tee AR, Manning BD, Roux PP, Cantley LC, Blenis J. Tuberous sclerosis complex gene products, Tuberin and Hamartin, control mTOR signaling by acting as a GTPase-activating protein complex toward Rheb. Curr Biol. 2003;13:1259–1268. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00506-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao X, Zhang Y, Arrazola P, et al. Tsc tumour suppressor proteins antagonize amino-acid-TOR signalling. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:699–704. doi: 10.1038/ncb847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inok K, Li Y, Zhu T, Wu J, Guan KL. TSC2 is phosphorylated and inhibited by Akt and suppresses mTOR signalling. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:648–657. doi: 10.1038/ncb839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goncharova EA, Goncharov DA, Eszterhas A, et al. Tuberin regulates p70 S6 kinase activation and ribosomal protein S6 phosphorylation. A role for the TSC2 tumor suppressor gene in pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM) J Biol Chem. 2002;277:30958–30967. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202678200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoki K, Zhu T, Guan KL. TSC2 mediates cellular energy response to control cell growth and survival. Cell. 2003;115:577–590. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00929-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter CJ, Pedraza LG, Xu T. Akt regulates growth by directly phosphorylating Tsc2. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:658–665. doi: 10.1038/ncb840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noda T, Ohsumi Y. Tor, a phosphatidylinositol kinase homologue, controls autophagy in yeast. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:3963–3966. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.7.3963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoreen CC, Kang SA, Chang JW, et al. An ATP-competitive mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor reveals rapamycin-resistant functions of mTORC1. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:8023–8032. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M900301200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanazawa T, Taneike I, Akaishi R, et al. Amino acids and insulin control autophagic proteolysis through different signaling pathways in relation to mTOR in isolated rat hepatocytes. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:8452–8459. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306337200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Kundu M, Viollet B, Guan KL. AMPK and mTOR regulate autophagy through direct phosphorylation of Ulk1. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:132–141. doi: 10.1038/ncb2152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorsey FC, Rose KL, Coenen S, et al. Mapping the phosphorylation sites of Ulk1. J Proteome Res. 2009;8:5253–5263. doi: 10.1021/pr900583m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shang L, Chen S, Du F, Li S, Zhao L, Wang X. Nutrient starvation elicits an acute autophagic response mediated by Ulk1 dephosphorylation and its subsequent dissociation from AMPK. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:4788–4793. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100844108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang SA, Pacold ME, Cervantes CL, et al. mTORC1 phosphorylation sites encode their sensitivity to starvation and rapamycin. Science. 2013;341:1236566. doi: 10.1126/science.1236566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamada Y, Funakoshi T, Shintani T, Nagano K, Ohsumi M, Ohsumi Y. Tor-mediated induction of autophagy via an Apg1 protein kinase complex. J Cell Biol. 2000;150:1507–1513. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.6.1507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamada Y, Yoshino K, Kondo C, et al. Tor directly controls the Atg1 kinase complex to regulate autophagy. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:1049–1058. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01344-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabeya Y, Kamada Y, Baba M, Takikawa H, Sasaki M, Ohsumi Y. Atg17 functions in cooperation with Atg1 and Atg13 in yeast autophagy. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:2544–2553. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-08-0669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraft C, Kijanska M, Kalie E, et al. Binding of the Atg1/ULK1 kinase to the ubiquitin-like protein Atg8 regulates autophagy. EMBO J. 2012;31:3691–3703. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott RC, Juhasz G, Neufeld TP. Direct induction of autophagy by Atg1 inhibits cell growth and induces apoptotic cell death. Curr Biol. 2007;17:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.10.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang YY, Neufeld TP. An Atg1/Atg13 complex with multiple roles in TOR-mediated autophagy regulation. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:2004–2014. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-12-1250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Wilson WA, Fujino MA, Roach PJ. Antagonistic controls of autophagy and glycogen accumulation by Snf1p, the yeast homolog of AMP-activated protein kinase, and the cyclin-dependent kinase Pho85p. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:5742–5752. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.17.5742-5752.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orlova M, Kanter E, Krakovich D, Kuchin S. Nitrogen availability and TOR regulate the Snf1 protein kinase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Eukaryot Cell. 2006;5:1831–1837. doi: 10.1128/EC.00110-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan HX, Russell RC, Guan KL. Regulation of PIK3C3/VPS34 complexes by MTOR in nutrient stress-induced autophagy. Autophagy. 2013;9:1983–1995. doi: 10.4161/auto.26058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martina JA, Chen Y, Gucek M, Puertollano R. MTORC1 functions as a transcriptional regulator of autophagy by preventing nuclear transport of TFEB. Autophagy. 2012;8:903–914. doi: 10.4161/auto.19653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Settembre C, Zoncu R, Medina DL, et al. A lysosome-to-nucleus signalling mechanism senses and regulates the lysosome via mTOR and TFEB. EMBO J. 2012;31:1095–1108. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu L, McPhee CK, Zheng L, et al. Termination of autophagy and reformation of lysosomes regulated by mTOR. Nature. 2010;465:942–946. doi: 10.1038/nature09076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatachalam K, Wong CO, Montell C. Feast or famine: role of TRPML in preventing cellular amino acid starvation. Autophagy. 2013;9:98–100. doi: 10.4161/auto.22260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vergarajauregui S, Connelly PS, Daniels MP, Puertollano R. Autophagic dysfunction in mucolipidosis type IV patients. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:2723–2737. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong CO, Li R, Montell C, Venkatachalam K. Drosophila TRPML is required for TORC1 activation. Curr Biol. 2012;22:1616–1621. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.06.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardie DG. AMP-activated protein kinase: an energy sensor that regulates all aspects of cell function. Genes Dev. 2011;25:1895–1908. doi: 10.1101/gad.17420111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Momcilovic M, Hong SP, Carlson M. Mammalian TAK1 activates Snf1 protein kinase in yeast and phosphorylates AMP-activated protein kinase in vitro. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:25336–25343. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604399200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawley SA, Selbert MA, Goldstein EG, Edelman AM, Carling D, Hardie DG. 5′-AMP activates the AMP-activated protein kinase cascade, and Ca2+/calmodulin activates the calmodulin-dependent protein kinase I cascade, via three independent mechanisms. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:27186–27191. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.45.27186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong SP, Leiper FC, Woods A, Carling D, Carlson M. Activation of yeast Snf1 and mammalian AMP-activated protein kinase by upstream kinases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:8839–8843. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1533136100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oakhill JS, Steel R, Chen ZP, et al. AMPK is a direct adenylate charge-regulated protein kinase. Science. 2011;332:1433–1435. doi: 10.1126/science.1200094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawley SA, Boudeau J, Reid JL, et al. Complexes between the LKB1 tumor suppressor, STRAD alpha/beta and MO25 alpha/beta are upstream kinases in the AMP-activated protein kinase cascade. J Biol. 2003;2:28. doi: 10.1186/1475-4924-2-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods A, Johnstone SR, Dickerson K, et al. LKB1 is the upstream kinase in the AMP-activated protein kinase cascade. Curr Biol. 2003;13:2004–2008. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2003.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao B, Heath R, Saiu P, et al. Structural basis for AMP binding to mammalian AMP-activated protein kinase. Nature. 2007;449:496–500. doi: 10.1038/nature06161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suter M, Riek U, Tuerk R, et al. Dissecting the role of 5′-AMP for allosteric stimulation, activation, and deactivation of AMP-activated protein kinase. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:32207–32216. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606357200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders MJ, Grondin PO, Hegarty BD, Snowden MA, Carling D. Investigating the mechanism for AMP activation of the AMP-activated protein kinase cascade. Biochem J. 2007;403:139–148. doi: 10.1042/BJ20061520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao B, Sanders MJ, Underwood E, et al. Structure of mammalian AMPK and its regulation by ADP. Nature. 2011;472:230–233. doi: 10.1038/nature09932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardie DG. AMP-activated/SNF1 protein kinases: conserved guardians of cellular energy. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:774–785. doi: 10.1038/nrm2249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan DF, Shackelford DB, Mihaylova MM, et al. Phosphorylation of ULK1 (hATG1) by AMP-activated protein kinase connects energy sensing to mitophagy. Science. 2011;331:456–461. doi: 10.1126/science.1196371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw RJ, Bardeesy N, Manning BD, et al. The LKB1 tumor suppressor negatively regulates mTOR signaling. Cancer Cell. 2004;6:91–99. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwinn DM, Shackelford DB, Egan DF, et al. AMPK phosphorylation of raptor mediates a metabolic checkpoint. Mol Cell. 2008;30:214–226. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bach M, Larance M, James DE, Ramm G. The serine/threonine kinase ULK1 is a target of multiple phosphorylation events. Biochem J. 2011;440:283–291. doi: 10.1042/BJ20101894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Kim YC, Fang C, et al. Differential regulation of distinct Vps34 complexes by AMPK in nutrient stress and autophagy. Cell. 2013;152:290–303. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaelin WG, Jr, Ratcliffe PJ. Oxygen sensing by metazoans: the central role of the HIF hydroxylase pathway. Mol Cell. 2008;30:393–402. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Cash TP, Jones RG, Keith B, Thompson CB, Simon MC. Hypoxia-induced energy stress regulates mRNA translation and cell growth. Mol Cell. 2006;21:521–531. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsin AS, Bertrand L, Rider MH, et al. Phosphorylation and activation of heart PFK-2 by AMPK has a role in the stimulation of glycolysis during ischaemia. Curr Biol. 2000;10:1247–1255. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00742-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsin AS, Bouzin C, Bertrand L, Hue L. The stimulation of glycolysis by hypoxia in activated monocytes is mediated by AMP-activated protein kinase and inducible 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:30778–30783. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205213200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell PH. Hypoxia-inducible factor as a physiological regulator. Experimental Physiol. 2005;90:791–797. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2005.030924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maynard MA, Ohh M. Molecular targets from VHL studies into the oxygen-sensing pathway. Curr Cancer Drug Rargets. 2005;5:345–356. doi: 10.2174/1568009054629672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Bosch-Marce M, Shimoda LA, et al. Mitochondrial autophagy is an HIF-1-dependent adaptive metabolic response to hypoxia. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:10892–10903. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800102200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Li Y, Wang Y, Kim E, et al. Bnip3 mediates the hypoxia-induced inhibition on mammalian target of rapamycin by interacting with Rheb. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:35803–35813. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705231200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brugarolas J, Lei K, Hurley RL, et al. Regulation of mTOR function in response to hypoxia by REDD1 and the TSC1/TSC2 tumor suppressor complex. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2893–2904. doi: 10.1101/gad.1256804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiling JH, Hafen E. The hypoxia-induced paralogs Scylla and Charybdis inhibit growth by down-regulating S6K activity upstream of TSC in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2879–2892. doi: 10.1101/gad.322704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeYoung MP, Horak P, Sofer A, Sgroi D, Ellisen LW. Hypoxia regulates TSC1/2-mTOR signaling and tumor suppression through REDD1-mediated 14-3-3 shuttling. Genes Dev. 2008;22:239–251. doi: 10.1101/gad.1617608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogura K, Wicky C, Magnenat L, et al. Caenorhabditis elegans unc-51 gene required for axonal elongation encodes a novel serine/threonine kinase. Genes Dev. 1994;8:2389–2400. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.20.2389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kundu M, Lindsten T, Yang CY, et al. Ulk1 plays a critical role in the autophagic clearance of mitochondria and ribosomes during reticulocyte maturation. Blood. 2008;112:1493–1502. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-02-137398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee EJ, Tournier C. The requirement of uncoordinated 51-like kinase 1 (ULK1) and ULK2 in the regulation of autophagy. Autophagy. 2011;7:689–695. doi: 10.4161/auto.7.7.15450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAlpine F, Williamson LE, Tooze SA, Chan EY. Regulation of nutrient-sensitive autophagy by uncoordinated 51-like kinases 1 and 2. Autophagy. 2013;9:361–373. doi: 10.4161/auto.23066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell RC, Tian Y, Yuan H, et al. ULK1 induces autophagy by phosphorylating Beclin-1 and activating VPS34 lipid kinase. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15:741–750. doi: 10.1038/ncb2757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Bartolomeo S, Corazzari M, Nazio F, et al. The dynamic interaction of AMBRA1 with the dynein motor complex regulates mammalian autophagy. J Cell Biol. 2010;191:155–168. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201002100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nazio F, Strappazzon F, Antonioli M, et al. mTOR inhibits autophagy by controlling ULK1 ubiquitylation, self-association and function through AMBRA1 and TRAF6. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15:406–416. doi: 10.1038/ncb2708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang HW, Wang YB, Wang SL, Wu MH, Lin SY, Chen GC. Atg1-mediated myosin II activation regulates autophagosome formation during starvation-induced autophagy. EMBO J. 2011;30:636–651. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itakura E, Kishi-Itakura C, Koyama-Honda I, Mizushima N. Structures containing Atg9A and the ULK1 complex independently target depolarized mitochondria at initial stages of Parkin-mediated mitophagy. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:1488–1499. doi: 10.1242/jcs.094110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webber JL, Tooze SA. Coordinated regulation of autophagy by p38alpha MAPK through mAtg9 and p38IP. EMBO J. 2010;29:27–40. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mack HI, Zheng B, Asara JM, Thomas SM. AMPK-dependent phosphorylation of ULK1 regulates ATG9 localization. Autophagy. 2012;8:1197–1214. doi: 10.4161/auto.20586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunlop EA, Hunt DK, Acosta-Jaquez HA, Fingar DC, Tee AR. ULK1 inhibits mTORC1 signaling, promotes multisite Raptor phosphorylation and hinders substrate binding. Autophagy. 2011;7:737–747. doi: 10.4161/auto.7.7.15491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung CH, Seo M, Otto NM, Kim DH. ULK1 inhibits the kinase activity of mTORC1 and cell proliferation. Autophagy. 2011;7:1212–1221. doi: 10.4161/auto.7.10.16660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loffler AS, Alers S, Dieterle AM, et al. Ulk1-mediated phosphorylation of AMPK constitutes a negative regulatory feedback loop. Autophagy. 2011;7:696–706. doi: 10.4161/auto.7.7.15451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Y, Pattingre S, Sinha S, Bassik M, Levine B. JNK1-mediated phosphorylation of Bcl-2 regulates starvation-induced autophagy. Mol Cell. 2008;30:678–688. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]