SUMMARY

T box riboswitches are cis-acting RNA elements that bind to tRNA and sense its aminoacylation state to influence gene expression. Here, we present the 3.2 Å resolution X-ray crystal structures of the T box Stem I-tRNA complex and tRNA, in isolation. T box Stem I forms an arched conformation with extensive intermolecular contacts to two key points of tRNA, the anticodon and D/T-loops. Free and complexed tRNA exist in significantly different conformations, with the contacts stabilizing flexible D/T-loops and a rearrangement of the D-loop. Using a designed T box RNA/tRNA system, we demonstrate that the T box riboswitch monitors the length and orientation of two essential contacts. Length or orientation mismatches engineered into the T box riboswitch and tRNA disrupt the complex, whereas simultaneous insertion of full helical turns realigns the interfaces and restores interaction between artificially elongated T box riboswitch and tRNA molecules.

INTRODUCTION

A paradigm shift in our understanding of genetic regulation took place in the past decade, with the discovery of cis-acting riboswitches that influence gene expression in response to metabolite concentrations. The term, riboswitch, is typically reserved for small molecule sensing RNAs that fold into complex tertiary structures with a ligand binding domain (aptamer) and a regulatory domain (effector) (Serganov and Nudler, 2013). Ligand binding to the aptamer induces a structural change in the effector to alter premature transcription termination or translation initiation. T box riboswitches occupy a unique niche in this paradigm by controlling genes, such as tRNA synthetases and amino acid importers, in response to a macromolecule, tRNA (Grundy and Henkin, 1993; Henkin et al., 1992). They directly bind tRNA to examine its anticodon, detect its aminoacylation state, and form a regulatory feedback loop to maintain appropriate aminoacylated tRNA levels (Grundy et al., 2000, 2002, 2005). Recent work suggests that tRNA recognition by the T box riboswitch can be conceptually divided into three steps: information decoding, geometry measurement, and then aminoacylation sensing (Grigg et al., 2013; Lehmann et al., 2013). The T box riboswitch structure is highly conserved (Gutiérrez-Preciado et al., 2009; Vitreschak et al., 2008) and consists of three stem loops (I–III) and a metastable effector domain that folds into either a transcription terminator or antiterminator (Green et al., 2010). Stem I is the largest element (~100 nucleotides) and provides the majority of the affinity for tRNA (Grigg et al., 2013). It consists of several conserved motifs: (1) the GA/kink-turn motif (Wang and Nikonowicz, 2011; Winkler et al., 2001); (2) the specifier loop, encoding a specifier sequence (codon) to recognize specific tRNA; (3) an L3/4 bulge; and (4) the AG Bulge and Distal Loop, which weave into a head-to-tail double T-loop module (Grigg et al., 2013; Lehmann et al., 2013). Recent evidence suggests that, in addition to the codon-anticodon interaction, the AG Bulge-Distal Loop region closely resembles RNase P and the ribosome tRNA binding sites and likely also forms a flat edge that base stacks against tRNA D/T-loops (Grigg et al., 2013; Lehmann et al., 2013). The anticodon pairing and D/T loop stacking contacts are hypothesized to provide both sequence specific decoding of cognate tRNA and structural selection by measuring the length between the anti-codon and D/T loops (Grigg et al., 2013; Lehmann et al., 2013).

To understand how the T box secures tRNA to affect expression, we used a T box construct found upstream of Geobacillus kaustophilus glyQ that was previously identified as the minimal T box structure required to robustly bind tRNAGly (nucleotides 10–96; Stem I86) (Grigg et al., 2013) and determined the 3.2 Å resolution cocrystal structure of Gkau T box Stem I86 bound to its cognate tRNAGly. A 3.2 Å tRNAGly structure in isolation was also determined for structural comparison. The cocrystal structure and subsequent mutagenesis experiments clearly demonstrate essential, conserved structural features for tRNA recognition by T box RNAs. Key T box RNA structural motifs, including the L3/4 kink, an S-turn motif, and extensive tertiary contacts from both strands of the specifier loop orient the proximal and sequence-specific tRNA anticodon loop binding sites. A second intermolecular contact forms between the distal Stem I86 base triple, thereby anchoring the tRNA D/T-loops. The data presented agree extremely well with the previous SHAPE and crosslinking data and reveal high-resolution details of the tRNA binding mechanism. Using our structural insight, we designed an artificial T box RNA system by covarying the length of Stem I and tRNAGly acceptor arms to demonstrate that the system makes both sequence and structurally dependent interactions. The overall architecture of our complex agrees well with an independently determined Oceanobacillus iheyensis glyQ T box Stem I-tRNA complex (Zhang and Ferré-D’Amaré, 2013); however, significant differences are found in local structural elements and the specifics of tRNA decoding, pointing to idiosyncratic tRNA recognition mechanisms among T box riboswitches.

RESULTS

Overall Stem I86-tRNAGly Structure

To reveal molecular details of tRNA anchoring to the T box riboswitch, we determined the 3.2 Å resolution Stem I86-tRNAGly complex crystal structure, using the apex Stem I structure (Protein Data Bank [PDB] ID code 4JRC) and a separately determined Gkau tRNAGly structure as molecular replacement search models (Table 1). The GA/k-turn motif, present in most, but not all T box riboswitches (Wang and Nikonowicz, 2011; Winkler et al., 2001), was removed for crystallization because it does not affect tRNA-binding affinity (Grigg et al., 2013). tRNAGly for both the complex and the stand-alone structure was produced by in vitro transcription and lacks biological modifications. Two Stem I86-tRNAGly complexes were identified in the asymmetric unit and clear electron density for the unmodeled portions were clearly visible following density modification (Figures S1 and S2A available online). Individual Stem I86 or tRNAGly molecules in the asymmetric unit superimpose with a root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of 1.7 and 1.1 Å over all C3′ atoms, respectively (Figure S2B). There is a slight lateral rotation difference between the two complexes, with the tRNAGly acceptor arm extending from Stem I86 with an ~7° lateral rotation. Other-wise, intermolecular contacts are indistinguishable, and subtle differences are localized to the main hinged regions in the Stem I86 structure at the top of P4, L3/4 and the specifier loop. We focused our structural analysis on chains A (Stem I86) and B (tRNAGly), which have lower temperature B-factors (chain A, 151 Å2; chain B, 109 Å2; chain C, 171 Å2; chain D, 131 Å2; Figure S2C) and more well-defined electron density. This high-resolution look at the complex allows us to clearly define key structural features for binding.

Table 1.

X-Ray Data Collection and Processing Statistics

| Stem I86-tRNAGly (Ba2+) | Stem I86-tRNAGly (Mg2+) | tRNAGly | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Collectiona | |||

| Beamline | APS 24ID-E | APS 24ID-E | CHESS A1 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.979 | 0.979 | 0.978 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 50–3.8 (3.87–3.80) | 50–3.2 (3.26–3.20) | 35–3.2 (3.26–3.20) |

| Space group | C2221 | C2221 | C2 |

| Unit cell dimensions (Å) | a = 92.8, b = 205.2, c = 182.2 | a = 92.8, b = 205.2, c = 182.2 |

a = 161.2, b = 28.4, c = 132.9 β = 110.7 |

| Unique reflections | 15,040 | 26,538 | 10,182 |

| Completeness (%) | 100 (99.9) | 98.8 (96.9) | 82.8 (46.2) |

| Multiplicity | 7.2 (6.6) | 6.9 (6.1) | 5.6 (4.0) |

| Average I/σI | 8.8 (2.0) | 14.1 (2.3) | 8.9 (3.1) |

| Rp.i.m. | 0.086 (0.393) | 0.099 (0.702) | 0.071 (0.154) |

| CC1/2b | 0.758 | 0.819 | 0.941 |

| Refinement | |||

| Rwork (Rfree) | – | 23.6 (27.8) | 24.5 (25.4) |

| B-factors (Å2), (number of atoms) | |||

| All atoms | – | 141.6 (6,850) | 118.8 (2,708) |

| RNA | – | 141.8 (6,832) | 119.0 (2,694) |

| Ions | – | 93.9 (18) | 83.1 (14) |

| Rmsd bond length (Å) | – | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| Rmsd bond angle (°) | – | 0.46 | 0.33 |

| PDB ID Codes | – | 4MGM | 4MGN |

See also Figure S1.

Data in parentheses represent the highest-resolution shell.

Correlation coefficient (see Karplus and Diederichs, 2012) for data in the highest-resolution shell only.

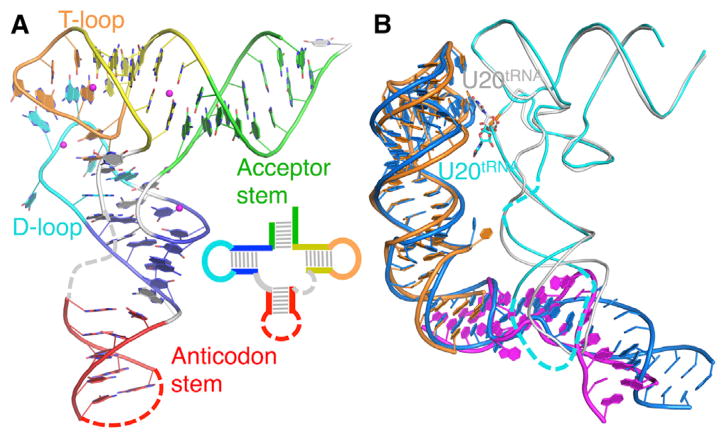

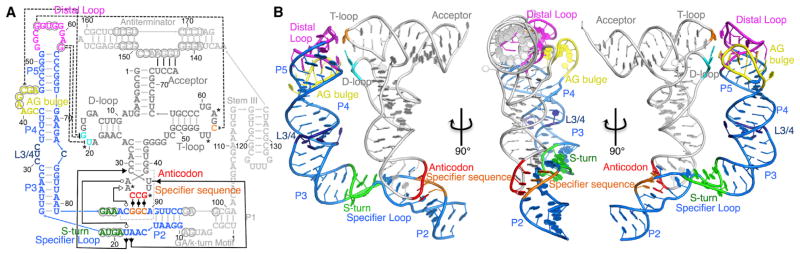

The ~110 Å long Stem I86 adopts an arched shape and packs alongside the tRNAGly anticodon arm. Structural distortions along Stem I86 facilitate two tRNAGly contacts (Figure 1). The AG Bulge-Distal Loop double T-loop structure bends the Stem I base stacking direction by 90°, enabling a triple-base stacking interaction between G62Tbox-C43Tbox•G55Tbox and C56tRNA-G19tRNA•U20tRNA from the tRNAGly D/T loops (Figures 2 and 3A). Another kink is introduced midstem by the CUC bulge (L3/4), which overtightens the helix pitch locally and directs P3 toward the minor groove side of the tRNAGly anticodon loop. The trend is enhanced by another kink at the S-turn motif in the upper specifier loop that creates a length mismatch, leading to a gradual compensatory arch at the lower half of the specifier loop and exposes the codon to base-pair with the tRNAGly anti-codon (Figure 1). The two specifier strands converge below the decoding site to coaxially stack with P2. Homology modeling (PDB ID code 2KZL) suggests that the deleted K-turn would project the 3′ portion of T box riboswitch toward the tRNAGly CCA tail, for aminoacylation sensing (Figure S2D). The complex is architecturally similar to a model derived from biochemical and small angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) analyses (Grigg et al., 2013; Lehmann et al., 2013) (Figures S2E, S3A, and S3B). Structural comparison suggests that both T box riboswitch and tRNAGly require subtle structural changes for binding. Complex formation induces three bends: one at the base of the apical double T-loop structure, another at L3/4 (Grigg et al., 2013), and multiple rearrangements at the specifier loop relative to an unbound NMR structure (Figures 2B, S3C, and S3D) (Wang et al., 2010; Wang and Nikonowicz, 2011). Conversely, localized tRNAGly changes are induced in the bound relative to free state (3.2 Å, this work) (Figure 2). The bound tRNAGly anticodon loop is ordered and less extended, whereas U19tRNA flips to anchor into the stacking interface. These structures strongly suggest that the T box RNA-tRNA interaction requires structural changes in both binding partners: a multijoint adjustment in Stem I and more localized rearrangements in tRNA.

Figure 1. Overall Structure of the T Box Stem I86-tRNAGly Complex.

(A) Secondary structure model. Regions of T box riboswitch in the crystal structure are shown in color; remaining regions are in light gray. Intermolecular base pairs are in solid black lines; base stacking is in dashed black lines; hydrogen bonds are in dashed gray lines; conserved residues are in circles; and tRNA modifications are in asterisks. tRNA numbering follows standard conventions.

(B) Cartoon representation of the Stem I86-tRNAGly crystal structure has been colored as in (A).

See also Figure S2.

Figure 2. Complex-Induced Structural Changes.

(A) The X-ray crystal structure of tRNAGly with key structural elements colored and shown schematically (inset). Dashed lines indicate disordered regions in the structure that could not be modeled.

(B) Structural change revealed by superposition of the complex with apical Stem I (gold), bottom Stem I (Magenta), and apo tRNA (cyan) structures.

See also Figure S3.

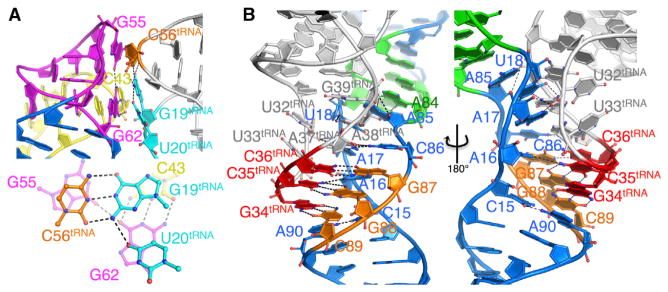

Figure 3. Structural Determinants for Stem I86-tRNAGly Binding.

(A) Base stacking interface to tRNA D/T loop shown in side and top-down orientations, with interface residues highlighted in sticks and hydrogen bonds in black dashed lines.

(B) Anticodon decoding through Stem I86 specifier loop and tRNAGly anticodon loop interactions.

See also Figure S4.

Base Stacking against the tRNA D/T Loops

The Stem I86 AG Bulge/Distal Loop double T-loop structure closely resembles our previously determined apical Stem I structure (PDB ID code 4JRC) (Grigg et al., 2013). In this element, the AG Bulge and Distal Loop are intertwined into a zipper-like structure of alternating stacked bases that overlay with the previously determined crystal structure of the distal Stem I (PDB ID code 4JRC; Stem I57), with an RMSD of 2.1 Å over all 57 C3′ atoms (Figures 2B and S3C). The relatively high RMSD for the analogous regions are a result of slightly altered hinge angles between segments (L3/4, P4/5) rather than localized structural differences. The double T-loop results in a G62Tbox-C43Tbox•G55Tbox base triple at the Stem I apex that provides the only tRNAGly D/T-loop contact (Figure 3A). C56tRNA stacks directly over G55Tbox and G19tRNA stacks between the G62Tbox-C43Tbox pair. U20tRNA tilt-stacks over the G62Tbox imidazole ring and accepts a hydrogen bond from G19tRNA N2. Notably, despite the interaction, space is available to accommodate common D-loop tRNA position 20 modifications, such as dihydrouridine (Figures 3A and S4C). The optimal G55Tbox/C56tRNA base stacking explains the tRNA-induced SHAPE protection at G55Tbox and the more disruptive mutagenesis effect compared to C43-G62Tbox mutations (Grigg et al., 2013). U20tRNA participation in the interface explains its occurrence as a prominent Stem I86-tRNAGly UV crosslinking site (Grigg et al., 2013). The interaction mode is similar to platforms in RNase P specificity domain (Reiter et al., 2010) and the 23S ribosomal RNA L1 stalk (Dunkle et al., 2011; Selmer et al., 2006); however, Stem I uniquely approaches along the anticodon arm with its interlocking T-loops reversed, such that the contacting loop approaches tRNA from the D- instead of T-loop side (Figures S3E–S3G). Given the differences, the interlocked T-loop structure is clearly a versatile tRNA binding platform.

Importance of the Internal Hinges

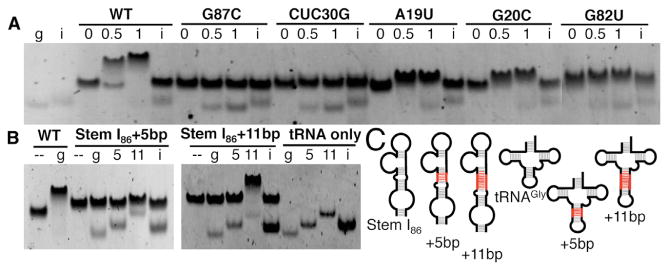

The same T box riboswitch scaffold recognizes diverse tRNAs with distinct surface features and modifications, indicating its robustness. Conformational differences between the two complexes in the asymmetric unit suggest that they are highly adaptable (Figure S2). The P3-L3/4-P4 angle differs slightly in the Stem I86-tRNAGly complex relative to the previously determined Stem I57 structure (Grigg et al., 2013) (Figure S3C), because the differences are small, and whether they are the result of tRNAGly binding or are simply driven by crystal packing is unclear. L3/4 includes the bulged C30U31C32Tbox on the opposite Stem I86 face relative to the tRNAGly binding sites, a conserved feature in T box RNAs, suggesting that it provides essential flexibility to Stem I for tRNA docking. To test the importance of L3/4, we used an established electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) for Stem I86-tRNAGly binding (Grigg et al., 2013). Reducing Stem I flexibility by substituting the CUC hinge (L3/4) with a WC pair completely disrupted complex formation and severely impaired T box function, on par with the effect of the codon mutation, G87C (Figure 4A). Overall, the inherent flexibility in the T box riboswitch seems to be optimally located to provide a highly adaptable and efficient binding platform.

Figure 4. Mutagenesis and Engineering an Artificial T Box-tRNA Interaction System.

(A) EMSAs in which T box mutants are incubated at 0, 0.5, and 1 molar ratio with tRNAGly (g) or tRNAIle (i).

(B) Helical insertions in tRNAGly or Stem I86. Stem I86 constructs for wild-type, 5 bp (Stem I86+5bp), and 11 bp (Stem I86+11bp) insertions are shown in the absence (−) or presence of equimolar tRNAGly constructs for wild-type (g), 5 bp insertion (5), 11 bp insertion (11), or tRNAIle (i) negative control.

(C) Schematics used in (B). Helical insertions highlighted in red.

Elaborate Structures Involved in tRNAGly Decoding

Information decoding of tRNA occurs at the T box specifier loop. The highly conserved distal 3–4 layers of nucleotides form an S-turn, similar to the sarcinricin loop of the 23S or 28S ribosomal RNA or Loop E motif (Hendrix et al., 2005; Rollins et al., 1997; Wang et al., 2010) (Figures 1, S2F, and S2G). EMSAs were used to probe the importance of the S-turn by making three mutations: G82UTbox induces an A22-U82 WC pair; G20CTbox disrupts the U21Tbox•A83Tbox•G20CTbox base triple, and finally, A19U disrupts A19Tbox•A84Tbox cis H/H pair. All three mutations impaired complex stability, as indicated by the smaller, smeared shift and presence of unbound tRNAGly in 1:1 conditions (Figure 4A). Notably, the S-turn mutations were not as disruptive as the G87CTbox codon replacement or L3/4 hinge replacement, suggesting that the structural integrity of the S-turn contributes cumulatively with other features to T box function.

The specifier sequence-anticodon interaction (G87G88C89Tbox-G34C35C36tRNA) is well defined in the density and forms the basis for cognate tRNA selection (Figure 3B). In contrast to A-minor motif-assisted decoding in 30S ribosome (Demeshkina et al., 2010), tertiary interactions directed at the specifier-anticodon triplet are largely absent in the T box-tRNA complex, suggesting mechanisms for proofreading and wobble position tolerance may not exist in T box riboswitches (Grundy and Henkin, 1993; Rollins et al., 1997). Instead, cognate specifier-anticodon pairing leads to additional tertiary interactions above and below the triplet to strengthen the decoding interface. In the specifier loop “coding” strand, A85Tbox makes a weak type II A-minor base triple to G39tRNA (A85Tbox•G39tRNA-C31tRNA) and a hydrogen bond to A19Tbox OP2; C86Tbox stacks on top of the codon and G87Tbox and forms a trans WC/S pair with A37tRNA. In the “noncoding” specifier strand, U18Tbox makes a WC-pair with A38tRNA. A17Tbox makes another type II A-minor interaction to U32tRNA; lack of interaction to the coplanar A37tRNA residue could accommodate common tRNA modifications, such as an N6-dimethylallyl adenine tRNA modification at A37tRNA (i6A; Figure S4) (Denmon et al., 2011). Similarly, tRNA wobble position modifications (i.e., Queuosine in place of G34tRNA) mostly target the Hoogsteen edge and are not expected to affect T box recognition. C15Tbox and A16Tbox are less well defined in the electron density, but the specifier loop strands converge below the triplet, where the highly conserved A90Tbox stacks directly below the C89Tbox-G34tRNA pair and forms a reverse Hoogsteen pair with C15Tbox, leading to the coaxial stacking of helix P2 underneath the tRNA anticodon loop. Because tRNA anticodon loop sequences vary significantly, understanding the conservation of these accessory tertiary contacts would require more sophisticated covariation analysis and multiple T box-tRNA structures for comparison.

Design of an Artificial T Box Response System

The cocrystal structure provided definitive evidence for our recent hypothesis that tRNA decoding by T box riboswitch involves the formation of two specific contacts that are individually weak but robustly anchor tRNA when present at their optimal orientation and distance. To convincingly demonstrate this cooperative-binding principle, we designed a set of length/orientation mismatch experiments. A 5 bp helical insertion in either the tRNAGly anticodon arm or Stem I86 P3 disrupted binding and could not be restored by a complementary insertion in its binding partner presumably because the two contacts are misaligned (Figure 4B). On the other hand, introducing an 11 bp extension (one full helical turn) to either RNA, disrupted complex formation, but a robust mobility shift, resembling wild-type, was restored when both insertions are present to match their length/orientation (Figure 4B). The success here opens the door to the utility of a set of artificial T box switches that can be differentially turned on/off by the expression of artificial tRNAs bearing different anticodons, up to 64 combinations, without affecting native tRNA levels.

DISCUSSION

The structures and mutagenesis presented in this work reveal intricate details for tRNAGly anchoring by the glyQS T box and exciting principles for anticodon decoding, helping to bring years of work on the system into focus. The crystal structure of the Stem I86-tRNAGly complex generally agrees with models for tRNA binding proposed by our group (Grigg et al., 2013) and Lehmann et al. (2013); however, structural rearrangements in both Stem I86 (kinking) and tRNAGly (U20) could not be deduced from the models and SAXS reconstructions alone (Grigg et al., 2013). The complex structure clearly reveals details for the distal tRNAGly docking platform that is formed by the head-to-tail double T-loops module (or interlocking T-loops) with tRNA (Grigg et al., 2013; Lehmann et al., 2013). The T-loop is a widespread structure involved in many RNA-RNA interactions (Chan et al., 2013), and the interlocking T-loops in Stem I are highly similar to those found at the tRNA D/T-loop binding interface of RNase P (Reiter et al., 2010) and the ribosome L1 stalk (Dunkle et al., 2011; Selmer et al., 2006), except that they are reversed in their docking direction against the tRNA D-loop instead of the tRNA T-loop (Figures S3E–S3G). The elements that form the interlocking T-loops of the glyQS T box RNA are highly conserved among T box leaders and are essential to their function (Grigg et al., 2013; Rollins et al., 1997). One obvious difference in the Gkau glyQS T box leader relative to other T box leaders is that the WC base paired C43 and G62 at the interface are conserved as adenosines in >80% of sequences (Gutiérrez-Preciado et al., 2009; Vitreschak et al., 2008) and are likely non-WC-paired, more closely resembling the interface formed in RNase P (Reiter et al., 2010) and the ribosome L1 stalk (Dunkle et al., 2011; Selmer et al., 2006). Despite these minor differences, the general structure and binding mechanism by the distal Stem I is likely conserved throughout these T box leaders.

In addition to the mRNA codon-tRNA anticodon base paring in the ribosome, tRNAs are anchored by numerous contacts along their length, and mRNA is oriented by numerous nonspecific interactions (Demeshkina et al., 2010). The tRNA anticodon loop is directly stabilized by contacts from both 23S and 16S rRNA contacts. The anticodon-codon interaction itself is stabilized in particular by two layers of A-minor motif interactions from the 30S ribosome, as a mechanism of proofreading in decoding. The distinct tertiary interactions to each of three anticodon-codon base planes result in wobble position tolerance. Decoding is additionally stabilized by tRNA modifications that influence cross-strand stacking or strengthen wobble base pairing (Demeshkina et al., 2010). Because a single RNA anchors tRNA in the T box system, it provides several tertiary contacts from both specifier loop strands to anchor tRNA. Most of the anchoring contacts target regions above and below the specifier-anticodon triplet, instead of the codon-anticodon triplet directly. The distal portion of the specifier loop contains the highly conserved S-turn that is essential for robust tRNA recognition. A similarly structured S-loop was observed in the tyrS T box RNA specifier loop NMR structure (Wang et al., 2010; Wang and Nikonowicz, 2011) and appears to position the tRNA decoding center by some concerted effort of changing nucleotide register in the helix to turn the specifier sequence bases toward the Stem I minor groove, changing the trajectory of the stem toward the anticodon and by causing a 1 nt bulge in the “coding” strand to further expose the codon WC edges. Below the S-loop, or the proximal side of the specifier loop, nucleotides are less conserved, but both strands are highly protected upon tRNA binding (Grigg et al., 2013; Yousef et al., 2005). The structure clearly reveals that extensive tertiary contacts are formed in less-conserved regions surrounding the anticodon-specifier sequence base pairs. Mutating the specifier sequence and the variable antiterminator sequence is generally sufficient to switch T box specificity in vivo; however, activity is often less robust or even inactive in some cases (Grundy and Henkin, 1993; Grundy et al., 1997; Putzer et al., 1995), highlighting the importance of additional interactions. Grundy et al. (1997) noted that changing tRNATyr to tRNAPhe preference also introduced variation at position 32 in the anticodon loop. Indeed, mutating it to A32C in tRNAPhe (as in tRNATyr) increased its complementary activity by 2-fold, providing key evidence that additional tertiary contacts in the anticodon loop were in fact involved in binding (Grundy et al., 1997). Additionally, nucleotides at positions 85–86 are not highly conserved and are often missing from T boxes all together, resulting in a shorter specifier loop than observed in the Gkau glyQS T box sequence (Gutiérrez-Preciado et al., 2009; Vitreschak et al., 2008). Previous studies demonstrated inserting a single nucleotide in the shorter tyrS specifier loop (Grundy and Henkin, 1993) in a position equivalent to positions 85–86 or deletion of extra bases (Yousef et al., 2005) had little effect on the function. This flexibility, despite the numerous supporting contacts, and those discussed at pertinent sections in the results clearly demonstrate that the T box riboswitch is capable of accommodating interface modifications in tRNA, especially at the commonly modified positions 20, 34, and 37 (Figure S4).

The only Stem I element missing in our complex structure is the bottom kink turn (K-turn), which we previously demonstrated does not appreciably contribute to the tRNA binding affinity (Grigg et al., 2013). In an independently determined O. iheyensis T box Stem I-tRNA complex structure, the K-turn is bound by a K-turn binding protein, YbxF, but does not make physical contact with tRNA (Zhang and Ferré-D’Amaré, 2013). Despite the differences in the angle of the kink between the free and YbxF-bound K-turn (Wang and Nikonowicz, 2011), the consensus appears to be that instead of contributing directly toward tRNA recognition, the function of this K-turn is to reorient and project the downstream T box structure toward tRNA CCA detail for aminoacylation sensing. The O. iheyensis T box-tRNA structure (Zhang and Ferré-D’Amaré, 2013) is highly similar to the Gkau Stem I86–tRNAGly structure, except for a few interesting differences. The O. iheyensis Stem I contains structurally similar apical interlocking T-loops; however, the tRNA base stacking platforms differ, with the base triple formed by C44-G63•A56 (equivalent to C43-G62•G55 in Gkau Stem I86). A56 is in the same conformation as Gkau G55 and stacks directly over the corresponding tRNA T-loop cytosine (C56), indicating the purines function similarly to stack against tRNA. The L3/4 bulge induces a similar sharp bend in both structures but is simply a 2 nt bulge rather than the 3 nt bulge in Gkau. L3/4 is not highly conserved in sequence or structure, indicating that it provides flexibility to the stem and is not structurally constrained. The most striking difference between the structures is found in the specifier loop. The O. iheyensis specifier loop is 2 nt shorter in both strands, resulting in a much more compact recognition site. The same S-turn/Loop E motif is found in the distal end of the specifier loop, bending the stem under the tRNA anticodon. In O. iheyensis Stem I, the Loop E motif leads directly into the specifier sequence, forming a seemingly rigid interaction. In Gkau Stem I86, the two additional nucleotides separate the Loop E motif and the specifier sequence (A17, U18, A85 and C86), where they form several tertiary contacts to the tRNA anticodon loop (Figures 1, 2, and 3). Given the previous observations that insertions and deletions are often tolerated at positions 85–86 (Grundy and Henkin, 1993; Yousef et al., 2005), it will be interesting to examine whether insertions allow an additional level of specificity for tRNA or whether they play a role in better accommodating specific tRNA modifications.

These data allow us to propose an updated model for the T box RNA-tRNA interaction. As the T box leader is being transcribed, Stem I folds and is able to robustly bind both charged and uncharged tRNA that bears the cognate codon, competitively. The tRNA is first specifically bound at its anticodon by the specifier sequence, which then induces additional contacts throughout the anticodon loop. These additional contacts provide additional affinity and specificity to securely anchor tRNA. Next, the structurally specific interaction forms between the tRNA D/T-loops that stack against the apex of Stem I. With tRNA securely anchored, as polymerase progresses through the remaining structural features, the GA/K-turn motif directs the antiterminator toward the tRNA acceptor arm. Finally, an antiterminator is formed with uncharged tRNA securely stabilizing the antiterminator or changed tRNA unable to bind, favoring formation of the terminator and thereby terminating transcription. The current model provides key insight into the mechanism of tRNA sensing, but several open questions remain. For instance, detailed kinetic analyses are needed to discern how rapidly tRNA is bound by Stem I and whether sensing of the charge state occurs in a speed compatible with RNA polymerase or whether transcription pausing sites may assist folding and selection. Given the high conservation of several elements identified in this work, the key principles of sequence and structural recognition should not only be a general feature of the widespread T box riboswitches but also of macromolecule-sensing riboregulators in general.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

RNA Transcription, Purification, and Refolding

G. kau Stem I86, tRNAGly, and tRNAIle transcription templates were assembled from nested PCR reactions and cloned into a modified pUC19 vector, as described previously (Grigg et al., 2013). Transcripts initiated with a T7 polymerase promoter, followed by the target RNA and flanked at the 3′ end by a Hepetitis-δ-virus ribozyme. Plasmid templates for crystallization and EMSAs were purified using QIAGEN MegaPrep and Invitrogen MidiPrep kits, respectively. The plasmids were linearized using HindIII, and RNAs were produced by in vitro transcription, as previously described (Ke and Doudna, 2004). RNAs were separated on 8% acrylamide denaturing gel electrophoresis, located by UV shadowing and excised. Gel slices were crushed an eluted into ddH2O. Eluted RNAs were buffer exchanged by at least three exchanges (40-fold dilution) in Millipore centrifugation columns (3,000 Da molecular weight cutoff). RNAs were diluted to 5 μM in 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.0) and 50 mM NaCl and heated in a heat block at 92°C for 2 min. The heat block was moved to room temperature, and samples were slow cooled to 65°C (~5 min). At that point, 10 mM MgCl2 was added, incubated 1 min, and then transferred onto ice. RNAs were then concentrated as required using Millipore centrifugation columns (3 kDa cutoff) or flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C for future use.

Crystallization and Data Collection

tRNAGly was concentrated to 3.6 mg/ml, and crystals were obtained in 75 mM NaCl, 2 mM CoCl2, 50 mM sodium cacodylate (pH 6.0), 30% w/v 1/6-Hexanediol, and 0.5 mM spermine. Crystals were frozen directly from the drop by plunging into liquid nitrogen. Data were collected on CHESS beamline A1. The Stem I86-tRNAGly complex was produced by mixing equimolar amounts of prefolded (2.5 μM final) Stem I86 and tRNAGly, incubating for 30 min at room temperature before concentrating to 5.7 mg/ml using a Millipore centrifugation column (10 kDa cutoff). Samples were then crystallized by hanging drop vapor diffusion in 4 μl drops containing 2 μl of RNA sample and 2 μl of well solution (80 mM NaCl, 20 mM MgCl2, 40 mM sodium cadodylate (pH 7.0), 12 mM spermine, and 10% 2-methyl-1,3 propanediol). Crystals grew to optimal size over 3–4 weeks and were cryoprotected by a quick wash in well solution with 30% 2-methyl-1,3 propanediol and flash cooled by plunging into liquid nitrogen. Data were collected using remote interface on beamline 24-ID-E at the Advanced Photon Source.

Data Processing and Structure Solution

tRNA and Stem I86-tRNAGly diffraction data were processed using HKL-2000 (Otwinowski and Minor, 1997). The data for tRNAGly and the StemI86-tRNAGly complex were anisotropic and therefore had inflated merging statistics. Data were not treated to remove anisotropy but were refined using Phenix. refine. The resolution cutoff for both data sets was determined by examining both I/σ and CC1/2, as described previously (Karplus and Diederichs, 2012). The extreme anisotropy in the case of tRNAGly alone, led to reduced overall completeness, but because the CC1/2 and I/σ values were still ideal, these resolution shells were included for refinement. Initial tRNAGly solutions were determined using the Escherichia coli tRNAPhe structure (PDB ID code 3LOU; Byrne et al., 2010) as a search model in Phaser-MR (McCoy et al., 2007) from the PHENIX program suite (Adams et al., 2010) to locate two molecules in the asymmetric unit. The structure was then manually built using Coot (Emsley et al., 2010) and RCrane (Keating and Pyle, 2012) and refined using PHENIX refine (Afonine et al., 2012). The final model comprised nucleotides 1–30, 38–42, and 45–72, as weak density for the anticodon loop precluded complete modeling. The initial 3.8 Å resolution Stem I86-tRNAGly data from conditions with 20 mM BaCl2 used in place of MgCl2 during crystallization were phased using our previous structure of the distal 57 nucleotides from Stem I (Stem I57; only the region containing P4, the AG bulge, P5, and the distal loop was used as a search model) (Grigg et al., 2013) and the tRNAGly crystal structure described above. Two tRNAGly molecules and one truncated Stem I57 were located using Phaser-MR (Adams et al., 2010). A second truncated Stem I57 in complex with tRNA could be seen in the phased maps and was located by running an additional round of Phaser-MR (McCoy et al., 2007) with the initial solution fixed. There was a weak, but detectable, anomalous signal from the barium atoms used in crystallization, and numerous strong Ba2+ peaks were evident in the maps, though the anomalous signal did not extend beyond ~5 Å for phasing. In total, 40 barium atoms were modeled into the initial density. In addition the tRNA anticodon was observed in the resulting map and density extending from the Stem I57 base to the anticodon was evident. Coot (Emsley et al., 2010) and RCrane (Keating and Pyle, 2012) were used to manually build into the existing density, and the structure was refined using PHENIX refine (Afonine et al., 2012), and Rosetta ERRASER (Chou et al., 2013) was used to facilitate further building. A higher resolution data set was obtained using crystals grown with MgCl2 in place of BaCl2. The data were anisotropic, with strongest diffraction observed to ~2.9 Å along a* with estimated resolution cutoffs of 2.9, 3.8, and 3.4 Å along a*, b*, and c*, respectively. Data anisotropy led to inflated merging statistics, and the 3.2 Å resolution cutoff was determined by examining both the I/σ and CC1/2, as described previously (Karplus and Diederichs, 2012). The structure was refined against the higher resolution data while preserving the Free-R flags between data sets. Finally, the structure was refined using torsional noncrystallographic symmetry and base pair restraints. The final model consists of all nucleotides in the construct, 10 to 95. Maps for building were either produced directly from PHENIX refine (Afonine et al., 2012) or generated using the “Create Maps” GUI in PHENIX (Adams et al., 2010) to apply B-factor sharpening or Autobuild (Terwilliger et al., 2008) for composite simulated annealing omit maps (Figure S1).

Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assays

Stem I86 constructs for the “Molecular Ruler” or mutagenesis experiments were diluted to 1.5 μM in 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.0), 50 mM NaCl, and 10 mM MgCl2 and mixed with equimolar (molecular ruler) or varied ratios (mutagenesis) of tRNAGly or tRNAIle. Samples were incubated at room temperature for 30 min and stored on ice until loading. Prior to loading 10% glycerol was added to samples, and 5 μl was loaded onto a prerun 6% acrylamide native Tris-borate gel supplements with 10 mM MgCl2. Gels were run in a 4°C room at a constant power of 10 W (~300 V) for ~4 hr and stained with Sybr Gold for visualization. Unfortunately, poor complex stability under EMSA conditions impeded determination of binding affinities (Grigg et al., 2013), so the EMSA assays were used as a qualitative test for large impairment to binding.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (GM-086766 to A.K.) and a postdoctoral fellowship from the Canadian Institute of Health Research (to J.C.G.). We thank Frank Grundy and Tina Henkin for introducing the G. kau glyQS T box system to us (Grigg et al., 2013) and Fang Ding and other members of the Ke lab for their support. This work is based upon research conducted at the Northeastern Collaborative Access Team beam-lines of the Advanced Photon Source and supported by an award (RR-15301) from the National Center for Research Resources at the National Institutes of Health. Use of the Advanced Photon Source is supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, under contract no. W-31-109-ENG-38. This work is also based on research that was also performed at the Cornell High Energy Synchrotron Source (CHESS; funding by the National Science Foundation [DMR-0936384]), using the Macromolecular Diffraction at the CHESS facility (MACCHESS; funded by NIGMS [GM103485]).

Footnotes

Supplemental Information includes four figures and can be found with this article online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.str.2013.09.001.

References

- Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunkóczi G, Chen VB, Davis IW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Hung LW, Kapral GJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afonine PV, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Moriarty NW, Mustyakimov M, Terwilliger TC, Urzhumtsev A, Zwart PH, Adams PD. Towards automated crystallographic structure refinement with phenix refine. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2012;68:352–367. doi: 10.1107/S0907444912001308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne RT, Konevega AL, Rodnina MV, Antson AA. The crystal structure of unmodified tRNAPhe from Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:4154–4162. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan CW, Chetnani B, Mondragon A. Structure and function of the T-loop structural motif in noncoding RNAs. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA. 2013;4:507–522. doi: 10.1002/wrna.1175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou FC, Sripakdeevong P, Dibrov SM, Hermann T, Das R. Correcting pervasive errors in RNA crystallography through enumerative structure prediction. Nat Methods. 2013;10:74–76. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demeshkina N, Jenner L, Yusupova G, Yusupov M. Interactions of the ribosome with mRNA and tRNA. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2010;20:325–332. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denmon AP, Wang J, Nikonowicz EP. Conformation effects of base modification on the anticodon stem-loop of Bacillus subtilis tRNA(Tyr) J Mol Biol. 2011;412:285–303. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunkle JA, Wang L, Feldman MB, Pulk A, Chen VB, Kapral GJ, Noeske J, Richardson JS, Blanchard SC, Cate JH. Structures of the bacterial ribosome in classical and hybrid states of tRNA binding. Science. 2011;332:981–984. doi: 10.1126/science.1202692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:486–501. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green NJ, Grundy FJ, Henkin TM. The T box mechanism: tRNA as a regulatory molecule. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:318–324. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.11.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigg JC, Chen Y, Grundy FJ, Henkin TM, Pollack L, Ke A. T box RNA decodes both the information content and geometry of tRNA to affect gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:7240–7245. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1222214110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundy FJ, Henkin TM. tRNA as a positive regulator of transcription antitermination in B. subtilis. Cell. 1993;74:475–482. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80049-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundy FJ, Hodil SE, Rollins SM, Henkin TM. Specificity of tRNA-mRNA interactions in Bacillus subtilis tyrS antitermination. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:2587–2594. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.8.2587-2594.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundy FJ, Collins JA, Rollins SM, Henkin TM. tRNA determinants for transcription antitermination of the Bacillus subtilis tyrS gene. RNA. 2000;6:1131–1141. doi: 10.1017/s1355838200992100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundy FJ, Moir TR, Haldeman MT, Henkin TM. Sequence requirements for terminators and antiterminators in the T box transcription antitermination system: disparity between conservation and functional requirements. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:1646–1655. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.7.1646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundy FJ, Yousef MR, Henkin TM. Monitoring uncharged tRNA during transcription of the Bacillus subtilis glyQS gene. J Mol Biol. 2005;346:73–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.11.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez-Preciado A, Henkin TM, Grundy FJ, Yanofsky C, Merino E. Biochemical features and functional implications of the RNA-based T-box regulatory mechanism. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2009;73:36–61. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00026-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrix DK, Brenner SE, Holbrook SR. RNA structural motifs: building blocks of a modular biomolecule. Q Rev Biophys. 2005;38:221–243. doi: 10.1017/S0033583506004215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henkin TM, Glass BL, Grundy FJ. Analysis of the Bacillus subtilis tyrS gene: conservation of a regulatory sequence in multiple tRNA synthetase genes. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:1299–1306. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.4.1299-1306.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karplus PA, Diederichs K. Linking crystallographic model and data quality. Science. 2012;336:1030–1033. doi: 10.1126/science.1218231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ke A, Doudna JA. Crystallization of RNA and RNA-protein complexes. Methods. 2004;34:408–414. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2004.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keating KS, Pyle AM. RCrane: semi-automated RNA model building. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2012;68:985–995. doi: 10.1107/S0907444912018549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann J, Jossinet F, Gautheret D. A universal RNA structural motif docking the elbow of tRNA in the ribosome, RNAse P and T-box leaders. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:5494–5502. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCoy AJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Adams PD, Winn MD, Storoni LC, Read RJ. Phaser crystallographic software. J Appl Cryst. 2007;40:658–674. doi: 10.1107/S0021889807021206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. In: Carter CW, Sweets RM, editors. Methods in Enzymology. Charlottesville: University of Virginia; 1997. pp. 307–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putzer H, Laalami S, Brakhage AA, Condon C, Grunberg-Manago M. Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase gene regulation in Bacillus subtilis: induction, repression and growth-rate regulation. Mol Microbiol. 1995;16:709–718. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiter NJ, Osterman A, Torres-Larios A, Swinger KK, Pan T, Mondragón A. Structure of a bacterial ribonuclease P holoenzyme in complex with tRNA. Nature. 2010;468:784–789. doi: 10.1038/nature09516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollins SM, Grundy FJ, Henkin TM. Analysis of cis-acting sequence and structural elements required for antitermination of the Bacillus subtilis tyrS gene. Mol Microbiol. 1997;25:411–421. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.4851839.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selmer M, Dunham CM, Murphy FV, 4th, Weixlbaumer A, Petry S, Kelley AC, Weir JR, Ramakrishnan V. Structure of the 70S ribosome complexed with mRNA and tRNA. Science. 2006;313:1935–1942. doi: 10.1126/science.1131127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serganov A, Nudler E. A decade of riboswitches. Cell. 2013;152:17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.12.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terwilliger TC, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Afonine PV, Moriarty NW, Adams PD, Read RJ, Zwart PH, Hung LW. Iterative-build OMIT maps: map improvement by iterative model building and refinement without model bias. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2008;64:515–524. doi: 10.1107/S0907444908004319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitreschak AG, Mironov AA, Lyubetsky VA, Gelfand MS. Comparative genomic analysis of T-box regulatory systems in bacteria. RNA. 2008;14:717–735. doi: 10.1261/rna.819308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Nikonowicz EP. Solution structure of the K-turn and Specifier Loop domains from the Bacillus subtilis tyrS T-box leader RNA. J Mol Biol. 2011;408:99–117. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Henkin TM, Nikonowicz EP. NMR structure and dynamics of the Specifier Loop domain from the Bacillus subtilis tyrS T box leader RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:3388–3398. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler WC, Grundy FJ, Murphy BA, Henkin TM. The GA motif: an RNA element common to bacterial antitermination systems, rRNA, and eukaryotic RNAs. RNA. 2001;7:1165–1172. doi: 10.1017/s1355838201002370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yousef MR, Grundy FJ, Henkin TM. Structural transitions induced by the interaction between tRNA(Gly) and the Bacillus subtilis glyQS T box leader RNA. J Mol Biol. 2005;349:273–287. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.03.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Ferré-D’Amaré AR. Co-crystal structure of a T-box riboswitch stem I domain in complex with its cognate tRNA. Nature. 2013;500:363–366. doi: 10.1038/nature12440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.