Abstract

Angiogenesis defines the process in which new vessels grow from existing vessels. Using the mouse retina as a model system, we show that cysteine-rich motor neuron 1 (Crim1), a type I transmembrane protein, is highly expressed in angiogenic endothelial cells. Conditional deletion of the Crim1 gene in vascular endothelial cells (VECs) causes delayed vessel expansion and reduced vessel density. Based on known Vegfa binding by Crim1 and Crim1 expression in retinal vasculature, where angiogenesis is known to be Vegfa dependent, we tested the hypothesis that Crim1 is involved in the regulation of Vegfa signaling. Consistent with this hypothesis, we showed that VEC-specific conditional compound heterozygotes for Crim1 and Vegfa exhibit a phenotype that is more severe than each single heterozygote and indistinguishable from that of the conditional homozygotes. We further showed that human CRIM1 knockdown in cultured VECs results in diminished phosphorylation of VEGFR2, but only when VECs are required to rely on an autocrine source of VEGFA. The effect of CRIM1 knockdown on reducing VEGFR2 phosphorylation was enhanced when VEGFA was also knocked down. Finally, an anti-VEGFA antibody did not enhance the effect of CRIM1 knockdown in reducing VEGFR2 phosphorylation caused by autocrine signaling, but VEGFR2 phosphorylation was completely suppressed by SU5416, a small-molecule VEGFR2 kinase inhibitor. These data are consistent with a model in which Crim1 enhances the autocrine signaling activity of Vegfa in VECs at least in part via Vegfr2.

Keywords: Crim1, Vegfa, Endothelial cell, Angiogenesis

INTRODUCTION

Angiogenesis defines the process in which new vessels grow from existing vessels through branching morphogenesis (Phng and Gerhardt, 2009; Geudens and Gerhardt, 2011). During angiogenesis, some vascular endothelial cells (VECs) in the originally quiescent vessels are induced to become tip cells. These cells are polarized and extend filopodia to probe microenvironmental cues, and migrate to lead the elongation of new vessel branches (Gerhardt et al., 2003). The VECs adjacent to tip cells become stalk cells, which proliferate and contribute to lumen formation (Gerhardt et al., 2003). Fusion of new sprouts in a process called anastomosis contributes to vascular network formation (Geudens and Gerhardt, 2011). This draft network then undergoes extensive remodeling to become functional (Potente et al., 2011). Dysregulated angiogenesis occurs in many pathological processes, including cancer (Gasparini et al., 2005), diabetic retinopathy (Crawford et al., 2009), retinopathy of prematurity (Flynn and Chan-Ling, 2006), and age-related macular degeneration (Jager et al., 2008), in which anti-angiogenic therapy can be of value (Gasparini et al., 2005).

The vascular endothelial growth factor (Vegf) family members are key regulators of vessel development and homeostasis. Vegfa is an indispensable pro-angiogenic factor in almost all non-pathological and pathological angiogenesis (Carmeliet and Jain, 2011). Vegfa signals via vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (Vegfr2; Kdr - Mouse Genome Informatics), a conventional tyrosine kinase receptor. Vegfr1 (Flt1 - Mouse Genome Informatics) is an inhibitory receptor because it binds Vegfa avidly but does not signal with high activity (Shibuya, 2001). There is also a soluble isoform of Vegfr1 that inhibits Vegfa through sequestration (Shibuya, 2001). During angiogenesis, Vegfa signals to VECs to promote tip cell formation [by enhancing expression of Dll4 (Phng and Gerhardt, 2009; Geudens and Gerhardt, 2011)], tip cell migration (Gerhardt et al., 2003), stalk cell proliferation (Gerhardt et al., 2003) and VEC survival via Akt (Gerber et al., 1998). Vegfr3 (Flt4 - Mouse Genome Informatics), a receptor for Vegfc, is restricted to the lymphatic vessels in the adult, but is upregulated during developmental angiogenesis in tip cells and during pathological angiogenesis (Tammela et al., 2011). It has recently been shown that VECs themselves are a source of Vegfa and that the ‘private loop’ of signaling via Vegfr2 within the VECs is crucial (Lee et al., 2007; Segarra et al., 2012). Mice in which Vegfa was deleted specifically in VECs showed postnatal mortality associated with vascular degeneration (Lee et al., 2007), suggesting a role for autocrine Vegfa in vascular homeostasis. Although it has been shown that endothelial cells upregulate Vegfa production under stress conditions, such as hypoxia (Namiki et al., 1995; Lee et al., 2007), other molecules involved in regulation of the ligand and downstream effectors of this pathway are largely unknown.

Cysteine-rich motor neuron 1 (Crim1) is a type I transmembrane protein that has N-terminal homology to insulin-like growth factor binding protein (IGFBP) domain and six cysteine-rich von Willebrand factor C (vWC) repeats, which are similar to those of chordin, a BMP antagonist (Kolle et al., 2000). Crim1 is expressed in multiple tissues and cell types, including the vertebrate CNS (Kolle et al., 2003; Pennisi et al., 2007), kidney (Wilkinson et al., 2007), eyes [including lens (Lovicu et al., 2000)] and the vascular system (Glienke et al., 2002; Pennisi et al., 2007; Wilkinson et al., 2007). It has been suggested that Crim1 has a role in vascular tube formation in vitro (Glienke et al., 2002). It is localized in endoplasmic reticulum and accumulates at cell-cell contacts upon stimulation of endothelial cells (Glienke et al., 2002). Mice homozygous for a gene-trap mutant allele (Crim1KST264) or germline mutants (Chiu et al., 2012) display perinatal lethality with defects in multiple organs, including hemorrhagic necrosis and enlarged glomerular capillary lumens (Wilkinson et al., 2007). The molecular function of Crim1 has been somewhat enigmatic, but it is known to form complexes with N-cadherin and β-catenin (Ponferrada et al., 2012) and to bind growth factors including Vegfa (Wilkinson et al., 2007; Wilkinson et al., 2009). In the glomerulus of the kidney, Crim1 on the cell surface of podocytes is proposed to regulate the delivery of Vegfa from podocytes to endothelial cells (Wilkinson et al., 2007; Wilkinson et al., 2009).

In the current study, based on the known Vegfa binding by Crim1 (Wilkinson et al., 2007) and the expression of Crim1 in retinal vasculature, we tested the hypothesis that Crim1 is involved in the autocrine activity of Vegfa. Consistent with this, VEC-specific conditional compound heterozygotes for Crim1 and Vegfa showed a phenotype more severe than each single heterozygote and indistinguishable from that of the conditional homozygotes. Human CRIM1 knockdown in cultured VECs resulted in diminished phosphorylation of VEGFR2, but only when VECs are required to rely on an autocrine source of VEGFA. VEGFA knockdown enhanced the effect of CRIM1 knockdown on reducing VEGFR2 phosphorylation. An anti-VEGFA antibody did not enhance the effect of CRIM1 knockdown in reducing VEGFR2 phosphorylation caused by autocrine signaling, but VEGFR2 phosphorylation was completely suppressed by SU5416, a small-molecule VEGFR2 kinase inhibitor. These data are consistent with a model in which Crim1 enhances the autocrine signaling activity of Vegfa in VECs at least in part via Vegfr2.

RESULTS

Crim1 is expressed in endothelial cells and pericytes

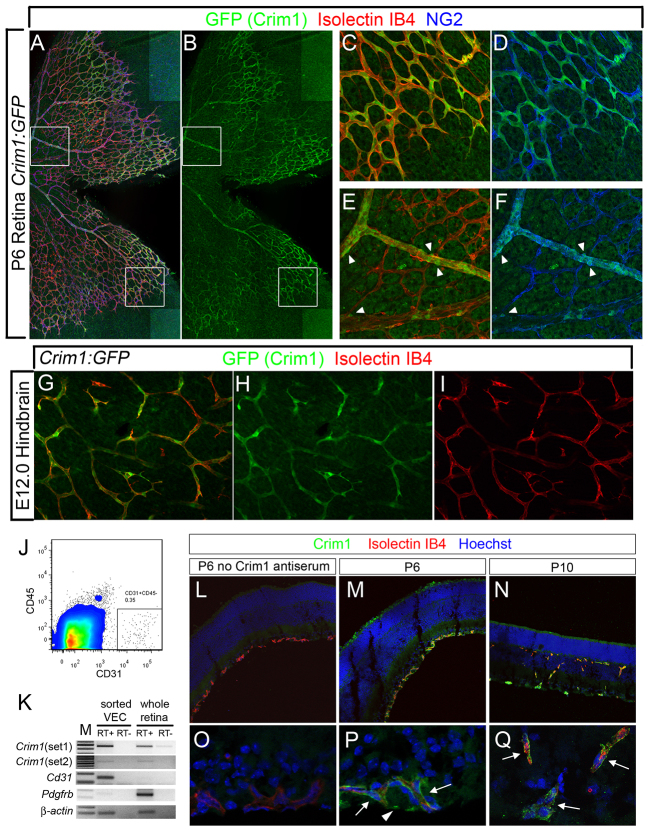

Crim1 is expressed in VECs in vitro and in vivo (Glienke et al., 2002). To examine the expression pattern of Crim1 in angiogenic vasculature, we analyzed flat-mounted preparations of mouse embryonic hindbrain and postnatal retinas from a Crim1:GFP mouse line (MGI: 4846966). In the vasculature of both organs, GFP was expressed in VECs marked by Isolectin IB4 (Fig. 1A-I). Notably, in the center of the retinal vascular plexus, the GFP intensity was lower in VECs but also present in smooth muscle cells marked by NG2 (Cspg4 - Mouse Genome Informatics) labeling (Fig. 1E,F, arrowheads). We also isolated CD31+ CD45- VECs from wild-type P7 mouse retinas by FACS (Fig. 1J). We confirmed cell identity by end-point RT-PCR detecting the endothelial cell marker Cd31 (Pecam1 - Mouse Genome Informatics) and the pericyte marker Pdgfrb (Fig. 1K). Crim1 transcripts were detected in retinal VECs using two different sets of primers (Fig. 1K). Crim1 protein was also labeled by immunofluorescence in P6 and P10 wild-type retinal sections using a newly developed antiserum. High immunoreactivity was observed in VECs labeled by Isolectin IB4 (Fig. 1M,N,P,Q), as well as in cells associated with the vasculature, which were probably pericytes (Fig. 1P, arrowheads). The expression of Crim1 in VECs indicated that it might have a role in vascular development.

Fig. 1.

Crim1 is expressed in endothelial cells and pericytes in angiogenic vasculature. (A-F) Flat-mounted P6 Crim1:GFP mouse retina labeled with isolectin IB4 and NG2 antibody. Enlarged images of the boxed regions (C-F) show colocalization of the GFP expression in isolectin-labeled endothelial cells and NG2-labeled pericytes/smooth muscle cells (arrowheads). (G-I) GFP signal was also detected in hindbrain vasculature of the E12.0 reporter mouse. (J) Representative FACS chart showing the endothelial cell population sorted from retina. (K) End-point RT-PCR in sorted endothelial cells and whole retina. For each primer set, PCR products were amplified with similar amounts of cDNA and the same cycle number. +/- RT, with and without reverse transcription. M, DNA size marker. (L-Q) Transverse sections of P6 and P10 retina labeled with Crim1 antiserum. No primary antibody was added in L,O. (O-Q) Higher magnification images. Arrows indicate Crim1 expression in endothelial cells; arrowhead indicates Crim1 expression in another cell type.

Validation of the Crim1flox allele

Crim1flox mice were crossed with the germline-expressed EIIa-Cre line to generate the Crim1Δflox allele. Mice homozygous for this allele did not show lethality until embryonic day (E) 17.5 (supplementary material Fig. S2A), but postnatally we identified only three live pups from over 20 litters, indicating that homozygotes died perinatally. Crim1Δflox/Δflox embryos exhibited anomalies that included peridermal blebbing, edema, hemorrhage (especially in the CNS), eye hypoplasia and syndactyly (supplementary material Fig. S2B-T). These changes phenocopy defects described in mice homozygous for the hypomorphic allele Crim1KST264 (Pennisi et al., 2007) and another germline null allele (Chiu et al., 2012) but occur with higher penetrance and severity (supplementary material Fig. S2B). These data validate Crim1flox as a conditional loss-of-function allele.

Deletion of Crim1 in VECs results in defective vascular development in the retina

We combined the Pdgfb-iCreER allele with Crim1flox and used daily intraperitoneal injection of tamoxifen starting at P1 or P7 (supplementary material Fig. S1C) to elicit Cre recombinase activity. Pdgfb-iCreER mice, upon tamoxifen administration, exhibit specific Cre activity in VECs including tip cells (Claxton et al., 2008) (supplementary material Fig. S1D). The Crim1flox allele was effectively recombined in retinal VECs as shown by genotyping PCR of DNA from FACS-sorted P7 endothelial cells (supplementary material Fig. S1E); the recombined Crim1flox allele was detected in tail DNA and retina DNA only when mice had the Pdgfb-iCreER allele (supplementary material Fig. S1B,E).

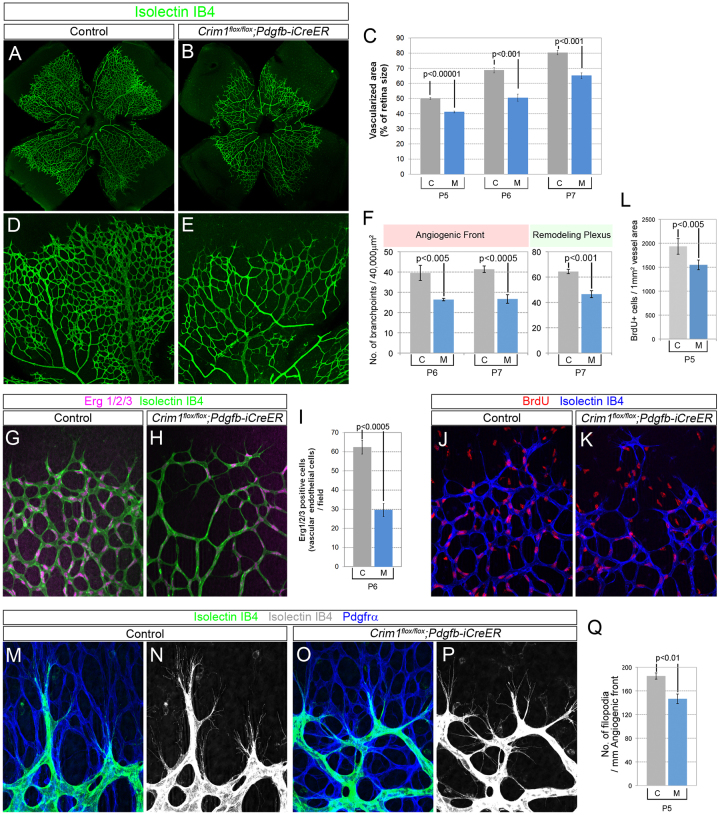

In the first postnatal week, a primary vascular plexus grows within the ganglion cell layer of the mouse retina through sprouting and anastomosis, expanding from the optic stalk and reaching the periphery by ∼P8 (Fruttiger, 2007). Tamoxifen-injected Crim1flox/flox; Pdgfb-iCreER pups showed delayed radial expansion of vasculature from center to periphery over a P5-P7 timecourse as compared with Cre-negative control littermates (Crim1flox/flox or Crim1flox/+) (Fig. 2A-C). More distinctively, vessel density as quantified by branchpoint number was also reduced in both the angiogenic front and remodeling plexus area behind the front (Fig. 2D-F).

Fig. 2.

Loss of Crim1 from endothelial cells causes reduced vessel growth in the primary plexus of the retinal vasculature. (A,B,D,E) Flat-mounted P6 mouse retina labeled with isolectin IB4. Crim1 VEC conditional mutant mice showed reduced vessel expansion to the periphery, as quantified in C. (F) Vessel density measured by counting branchpoint number in randomly selected 200 μm × 200 μm fields (five fields per retina). (G,H) High-magnification images showing anomalies in vascular morphology at the angiogenic front in P6 Crim1 VEC mutant mice. (I) Quantification of Erg1/2/3 antibody-labeled VEC nuclei per field. (J-L) Two-hour BrdU incorporation experiment showed a reduced VEC proliferation profile in P5 Crim1 VEC mutant pups. BrdU incorporation (cell number) was normalized to vessel-covered area, as labeled by Isolectin IB4. (M-P) Filopodia in Crim1 VEC conditional mutant mice extend along a preformed astrocyte template labeled with Pdgfrα antibody. Filopodia number was quantified and normalized to the outline of the angiogenic front. (C,F,I,L,Q) M, Crim1flox/flox; Pdgfb-iCreER pups; C, control littermates. At least five retinas of each genotype were analyzed in every experiment. Error bars represent s.e.m.

Starting at P7-P8, vessels sprout into the outer plexiform layer (OPL) and then turn, sprout and connect to form the deep vascular layer that resides between the OPL and the photoreceptors (Fruttiger, 2007). Crim1flox/flox; Pdgfb-iCreER pups injected with tamoxifen from P7 to P10 exhibited a delayed invasion of vasculature into the deepest layer (supplementary material Fig. S3A-D), as shown by fewer vertical sprouts, reduced branchpoint number and reduced total vessel length (supplementary material Fig. S3E-G). Combined, these data showed that endothelial Crim1 plays a role throughout retinal vascular development.

Loss of Crim1 from endothelial cells caused abnormal vessel morphology and compromised VEC proliferation

The initial density of the sprouting vasculature can be affected by tip cell number (Hellström et al., 2007; Phng et al., 2009; Larrivée et al., 2012). The angiogenic front in Crim1 VEC conditional mutants was hypocellular compared with that of wild-type littermates, as indicated by Erg1/2/3 antibody labeling of the VEC nuclei (Fig. 2G-I). In addition, a much higher occurrence of vessel segments of small caliber was observed in Crim1 VEC conditional mutant mice (Fig. 2E,H).

Two-hour BrdU incorporation showed a reduced number of S-phase VECs in the conditional mutant pups (Fig. 2J-L). Tip cells of the Crim1 VEC conditional mutant mice exhibited a mildly reduced density of filopodia, but these filopodia were still closely attached to the underlying astrocytes (Fig. 2M-Q). Expression of the Notch pathway target Vegfr3 was normal in VEC conditional mutants (supplementary material Fig. S4), suggesting that loss of Crim1 from VECs was unlikely to disrupt the Notch signaling pathway.

Endothelial loss of Crim1 results in defective cell adhesion molecule distribution and precocious vessel regression

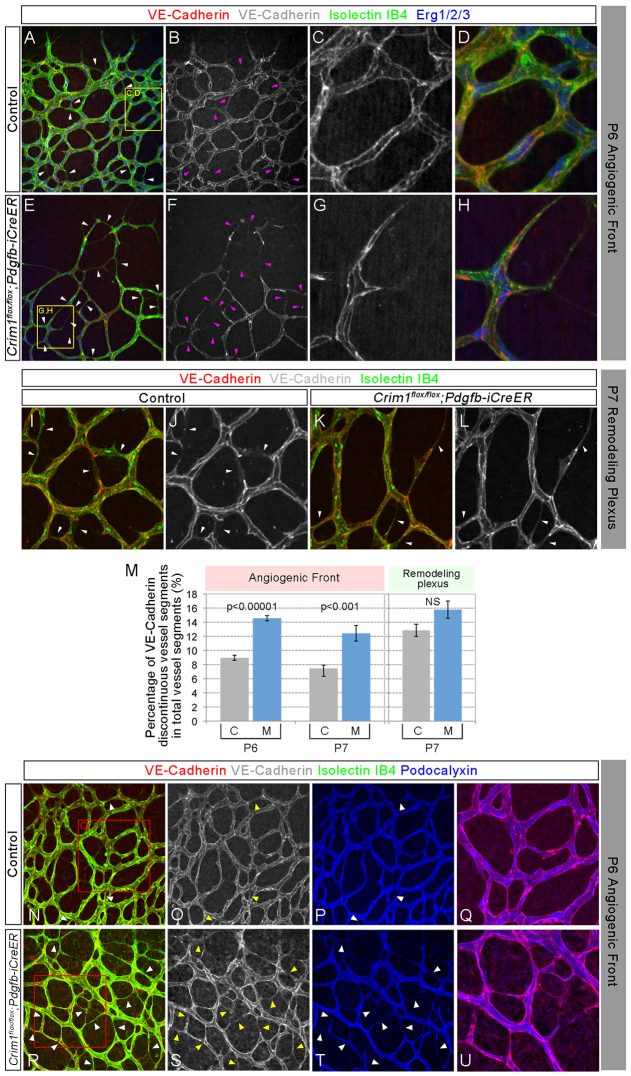

Previous studies from our laboratory indicated that Crim1 has an active role in promoting neuroepithelium cell adhesion through regulation of cadherin-catenin complexes (Ponferrada et al., 2012). Other investigators also showed that Crim1 accumulates at endothelial cell-cell contacts under certain conditions (Glienke et al., 2002). Given the important role that the adhesion molecule VE-cadherin plays in initiating anastomosis (Hoelzle and Svitkina, 2012) and maintaining vessel stability (Dejana et al., 2009; Phng et al., 2009), we assessed the possibility of a cell adhesion anomaly in Crim1flox/flox; Pdgfb-iCreER mouse retinal vasculature.

We observed an increase in vessel segments with discontinuous VE-cadherin labeling in Crim1 conditional mutants (Fig. 3A-L) (one vessel segment is defined as an isolectin-labeled connection between two branchpoints). This change was more significant at the angiogenic front (Fig. 3M). VE-cadherin-negative segments were usually of reduced caliber. In addition, podocalyxin labeling, which marks the apical/luminal side of the vessels, was missing in VE-cadherin-negative regions (Fig. 3N-P,R-T, arrowheads). In summary, Crim1 VEC conditional mutant mice had a higher percentage of thin, cadherin-deficient, non-lumenized vessel segments.

Fig. 3.

Abnormal adhesion junction distribution in Crim1 VEC conditional mutants. (A-L) Antibody labeling in flat-mounted retina preparations shows VE-cadherin distribution in the P6 angiogenic front (A-H) and P7 remodeling plexus (I-L) areas. White and pink arrowheads point to vessel segments without continuous VE-cadherin distribution. (M) Quantitation of vessel segments without continuous junctional VE-cadherin signal (normalized to total Isolectin IB4-labeled segments). M, Crim1flox/flox; Pdgfb-iCreER pups; C, control littermates. At least five retinas of each genotype were analyzed at P6 or P7. Error bars represent s.e.m. (N-U) VE-cadherin and podocalyxin colabeling showing that VE-cadherin-deficient vessel segments, which occurred more frequently in Crim1flox/flox; Pdgfb-iCreER pups, did not have a lumen (white and yellow arrowheads).

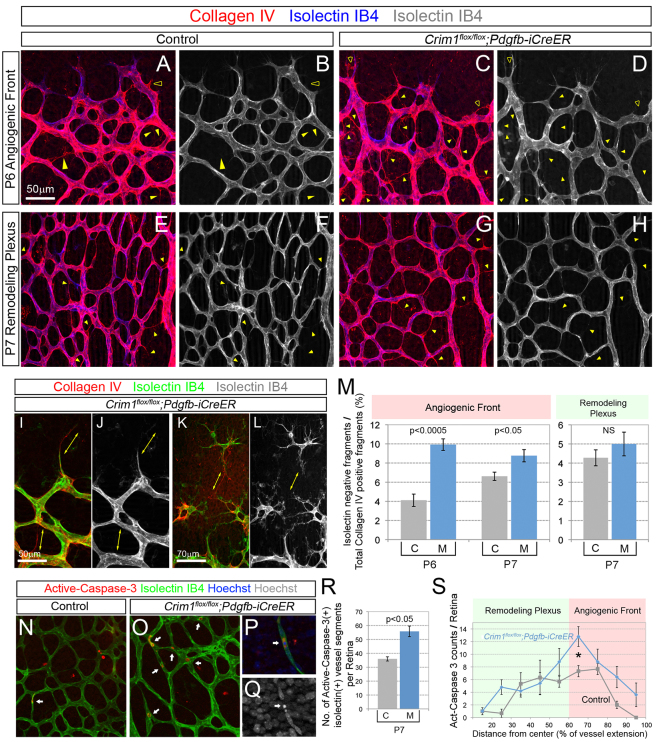

Normally, vessel pruning occurs mostly around arteries where the oxygen level is high (Adini et al., 2003; Phng et al., 2009). Regressed vessel segments appear as ‘vessel ghosts’, which are labeled for vascular basement membrane markers such as collagen IV but lack isolectin-positive VECs (Phng et al., 2009). In Crim1flox/flox; Pdgfb-iCreER pups, there was a significant increase in vessel ghosts at the angiogenic front (Fig. 4A-D,M) but no significant increase within the remodeling plexus (Fig. 4E-H,M). We observed several cases of retracted sprouts (Fig. 4I,J) and vessel fragments completely disconnected from the vessel bed (Fig. 4K,L).

Fig. 4.

Depletion of Crim1 from endothelial cells causes precocious vessel regression. (A-H) Flat-mounted retinas labeled with Isolectin IB4 and collagen IV antibody. Collagen IV-positive and Isolectin IB4 labeling-negative vessel segments represented regressed capillaries, e.g. vessel ghosts (filled arrowheads) and retracted sprouts (empty arrowheads). The increase in vessel ghosts was more obvious at the angiogenic front (A-D) than in the remodeling plexus (E-H). Several cases of long retracted sprouts (I,J) or endothelial cells detaching from the vessel bed (K,L) were observed. (M) Quantification of vessel ghosts. (N-Q) Active caspase 3 labeling of retinas. Vessel segments with active caspase 3-labeled endothelial cells increase in Crim1 conditional mutant pups (O, arrows). Active caspase 3 labeling coincided with DNA fragmentation (P,Q, arrows). (R) Quantification of vessel segments with active caspase 3-labeled endothelial cells. (S) Occurrence of active caspase 3-positive vessel segments at different distances from the center of the retina (relative to vessel expansion); *P<0.05. (M,R,S) M, Crim1flox/flox; Pdgfb-iCreER pups; C, control littermates. At least five retinas of each genotype were analyzed in every experiment. Error bars represent s.e.m.

We also labeled active caspase 3, an early marker for apoptosis (Fig. 4N-Q). The VEC apoptosis index was significantly higher in Crim1flox/flox; Pdgfb-iCreER retinas than in control retinas (Fig. 4N,O,R). We measured the distance of dying vessel fragments from the center of the retina and found that the increase in apoptosis in the VEC conditional mutant mice was most apparent within the region between 60% and 70% of the distance to the edge of the angiogenic front. This corresponds to the more angiogenically active vessel front (Fig. 4S). Mural cells recruited to newly formed capillaries are also crucial for vessel stability (Gerhardt and Betsholtz, 2003). In Crim1flox/flox; Pdgfb-iCreER mutant pups, the attachment of desmin+ (supplementary material Fig. S5) or NG2+ pericytes (data not shown) to VECs at the angiogenic front was not compromised, although smooth muscle actin (SMA) showed mildly reduced labeling around arteries (supplementary material Fig. S5E-H). This suggested that depletion of Crim1 from VECs did not have a significant effect on mural cells. Combined, these data suggest that loss of Crim1 from VECs causes instability of newly formed vessels, resulting in vessel fragmentation and precocious regression.

Crim1 and Vegfa function cooperatively in retinal vasculature development

Previous studies showed that Crim1, via its cysteine-rich motif, is able to physically bind ligands bearing a cysteine-knot motif, including several BMPs, PDGF and VEGFA, before their secretion (Wilkinson et al., 2003; Wilkinson et al., 2007). This, and the Vegfa dependence of retinal angiogenesis, raised the possibility that Crim1 might regulate Vegfa activity. In the retina, in the first postnatal week, Vegfa transcript is found in astrocytes and neurons (Fruttiger, 2007; Rao et al., 2013). Vegfa protein becomes tethered to the extracellular matrix of astrocytes in avascularized regions ahead of the angiogenic front (Gerhardt et al., 2003; Stenzel et al., 2011). In addition to paracrine Vegfa, VEC-derived autocrine Vegfa signaling has been implicated in vessel homeostasis (Lee et al., 2007).

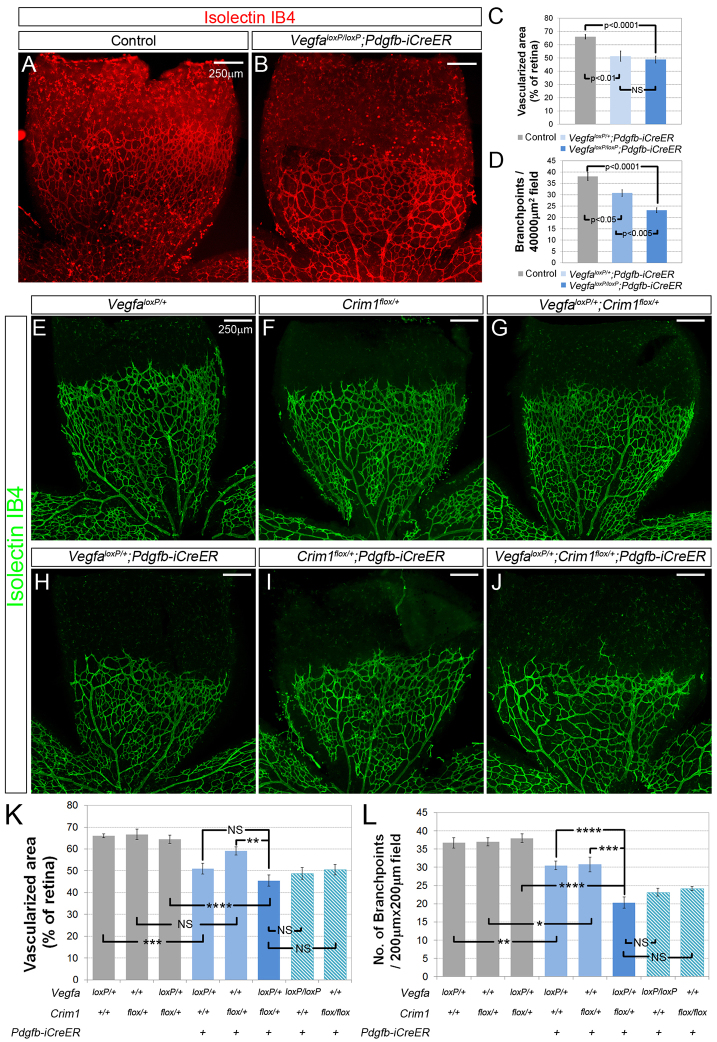

To examine whether autocrine signaling is also required for angiogenesis in vivo, we generated Vegfa VEC conditional knockout mice by crossing the Pdgfb-iCreER line to the VegfaloxP line (Gerber et al., 1999) and induced Cre activity by tamoxifen injection. Compared with Cre-negative control littermates, conditional heterozygotes and homozygotes showed a reduced vascularized area (Fig. 5A-C) and a Vegfa dose-dependent reduction in vessel density (Fig. 5A,B,D). This phenotype has many similarities to the Crim1 VEC conditional phenotype. In particular, Vegfa conditional deletion results in many more collagen IV+, isolectin-negative vessel ghosts (supplementary material Fig. S6A,B,E,F) and vessel segments that show discontinuous VE-cadherin labeling (supplementary material Fig. S6C,D,G,H). Furthermore, like the Crim1 conditional mutant, in the Vegfa conditional mutant discontinuous VE-cadherin labeling correlated with the absence of podocalyxin, suggesting the absence of a lumen. Combined, these data confirm that VECs are a biologically important source of Vegfa (Lee et al., 2007) and indicate that the Crim1 and Vegfa VEC loss-of-function phenotypes are very similar.

Fig. 5.

VEC-derived Crim1 and Vegfa function cooperatively in retinal vasculature development in vivo. (A,B) Flat-mounted P6 retina preparations labeled with Isolectin IB4 showing slightly reduced vessel expansion to the periphery of the retina and greatly decreased vessel density in Vegfa VEC conditional mutant pups. (C,D) Quantitation of vascularized area (normalized to retina size) and vessel density, as measured by branchpoint number in randomly selected fields. (E-J) Flat-mounted P6 retina preparations of the indicated genotypes labeled with Isolectin IB4. (K,L) Quantitation of vascularized area (normalized to retina size) and vessel density of retinal vasculature from mice of the indicated genotypes. At least five retinas of every genotype were analyzed. Numbers of Crim1flox/flox; Pdgfb-iCreER and VegfaloxP/loxP; Pdgfb-iCreER retinas were obtained from other crosses (see Fig. 2C,F and Fig. 7C,D) and reused here. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.005; ****P<0.001; NS, not significant. Error bars represent s.e.m. Scale bars: 250 μm.

One means to assess whether Crim1 might regulate Vegfa function in vivo is to generate compound conditional mutants and perform a quantitative assessment of the phenotype. In this way, it is possible to determine whether two molecules contribute to the same biological process. Thus, we combined the VegfaloxP, Crim1flox and Pdgfb-iCreER alleles and found that both VegfaloxP/+; Pdgfb-iCreER and Crim1flox/+; Pdgfb-iCreER heterozygotes showed mildly reduced expansion of the vasculature as well as vessel density (Fig. 5H,I compared with 5E,F). Interestingly, the VegfaloxP/+; Crim1flox/+; Pdgfb-iCreER double heterozygotes exhibited much more severely defective angiogenesis than either of the single heterozygotes (Fig. 5H-J) and recapitulated the retinal vascular phenotypes of Crim1 or Vegfa VEC-specific knockouts (Fig. 5K,L). This synthetic phenotype suggests that Crim1 and Vegfa function in the same pathway.

CRIM1 promotes autocrine VEGFA-VEGFR2 signaling within endothelial cells

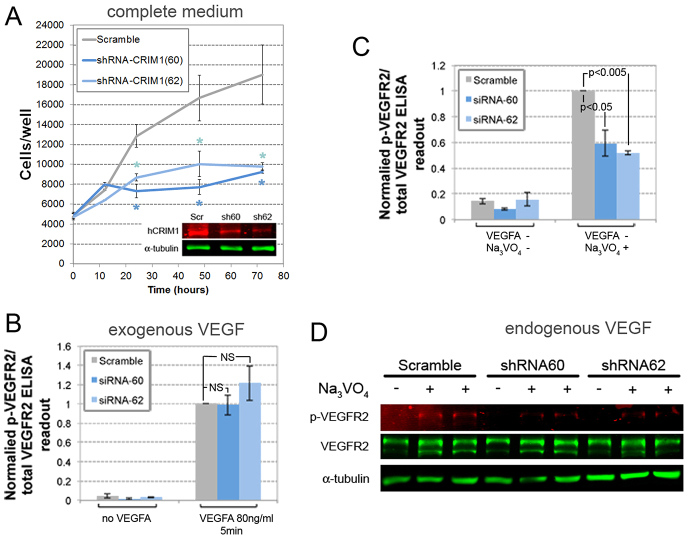

In order to examine directly the possibility that Crim1 regulates Vegfa signaling, we established lentiviral shRNA-mediated knockdown of CRIM1 in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs). Two different shRNAs were able to knock down CRIM1 by 60-70% at the protein (Fig. 6A) and transcript (Fig. 7D) levels. Measured by MTT assay, the growth of CRIM1 knockdown HUVECs cultured in complete medium was greatly suppressed (Fig. 6A), suggesting a functional requirement. The localization of VE-cadherin and β-catenin as well as of VEGFR2 was unchanged in these knockdown cells (supplementary material Fig. S7A-F,J-O).

Fig. 6.

Crim1 promotes VEGFA-VEGFR2 autocrine signaling in endothelial cells. (A) Growth curve of HUVECs infected by lentiviral particle expressing scramble shRNA and shRNAs specific for CRIM1. 5000 cells were plated into each well of fibronectin-coated 96-well plates at time zero. Efficiency of knocking down CRIM1 protein with shRNAs was shown by immunoblot (inset). *P<0.01, three independent experiments. (B) VEGFR2 phosphorylation in response to VEGFA stimulation. Control and CRIM1-deficient cells were starved for 24 hours and stimulated with 80 ng/ml recombinant human VEGFA for 5 minutes. Cell lysates were collected and analyzed using phospho-VEGFR2 and VEGFR2 ELISA kits and the ratio of phospho-VEGFR2 and total VEGFR2 readouts calculated. Measurements were normalized to that of control HUVECs stimulated with recombinant human VEGF. Error bars represent the s.e.m. of three independent experiments. (C) VEGFR2 phosphorylation without exogenous VEGFA. Control and CRIM1 knockdown HUVECs were cultured in serum-free and VEGFA-depleted culture medium with or without 0.1 mg/ml Na3VO4 (to inhibit phosphatase activity) for 24 hours. Cell lysates were collected and analyzed using phospho-VEGFR2 and VEGFR2 ELISA kits and the ratio of the two calculated. All readouts were normalized to that of control HUVECs. Error bars represent s.e.m. of three independent experiments. (D) Immunoblot of whole cell lysates of control and CRIM1-deficient HUVECs cultured in VEGFA-depleted medium with or without addition of 0.1 mg/ml Na3VO4.

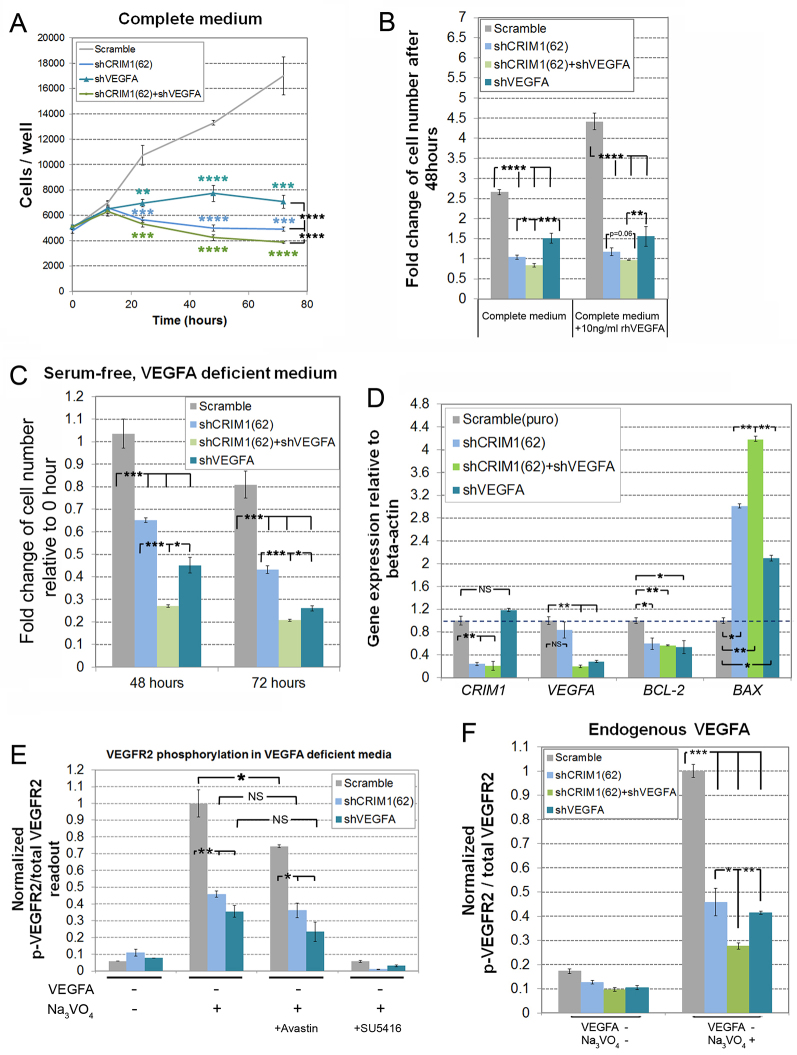

Fig. 7.

Relative impacts and combined impact of VEGFA and CRIM1 knockdown on VEGFR2 signaling. (A) Growth curve of HUVECs expressing scramble shRNA and shRNAs targeting CRIM1, VEGFA or a combination of both. Colored asterisks indicate statistical significance between control and respective experimental groups. (B) Fold change in cell number after 48 hours compared with time zero of cells incubated in complete medium (EGM-2) or complete medium with addition of 10 ng/ml recombinant human (rh) VEGFA. (A,B) 5000 cells were plated into each well of 96-well plates at time zero. (C) Fold change in cell number after 48 hours incubation in serum-free EGM-2 without addition of supplemental VEGFA. 20,000 cells were plated in each well at time zero. (D) Gene expression measured by quantitative RT-PCR. Cells were cultured in fresh complete medium for 24 hours. Level of mRNA expression was normalized to that of β-actin. All error bars represent s.e.m. of three experiments. (E) VEGFR2 phosphorylation without exogenous VEGFA. Cells were incubated for 24 hours in serum-free EGM-2 without addition of supplemental VEGFA and with 0.1 mg/ml Na3VO4. In one set of experiments, the medium was pre-incubated with 10 μg/ml Avastin for 2 hours and then applied to the cells. In another set of experiments, medium contained 0.5 μM SU5416. (F) VEGFR2 phosphorylation without exogenous VEGFA. HUVECs infected by lentiviral particles expressing scramble shRNA and shRNAs targeting CRIM1, VEGFA or a combination of the two were incubated in serum-free, VEGFA-depleted medium containing 0.1 mg/ml Na3VO4 for 24 hours before cell lysates were analyzed by phospho-VEGFR2 and VEGFR2 ELISA and the ratio of the two readouts calculated. All error bars represent s.e.m. of three independent experiments. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.005; ****P<0.001; NS, not significant.

To test directly whether CRIM1 is involved in VEGFA-VEGFR2 signaling, we stimulated HUVECs with recombinant VEGFA and assessed the VEGFR2 phosphorylation level using ELISA (Fig. 6B). With exogenous VEGFA at 80 ng/ml, CRIM1 knockdown HUVECs showed no change in the ratio of phosphorylated to total VEGFR2 (Fig. 6B). When we tested different concentrations of exogenous VEGFA (2 to 20 ng/ml), CRIM1 knockdown also had no effect on VEGFR2 phosphorylation (supplementary material Fig. S8B). Interestingly, however, when we cultured HUVECs in VEGFA-deficient medium for 24 hours and added Na3VO4 to inhibit phosphatase activity, we recorded a significant reduction of VEGFR2 phosphorylation in the CRIM1 knockdown cells. This response was quantified by ELISA (Fig. 6C) but was also observed by immunoblot (Fig. 6D). These data suggested that CRIM1 modulates the autocrine signaling response to VEGFA.

To examine this possibility further, we assessed the relative impact and the combined impact of VEGFA and CRIM1 knockdown on the growth of HUVECs and on VEGFR2 signaling. In complete medium with a low supplemental level of VEGFA (∼2 ng/ml), VEGFA or CRIM1 knockdown HUVECs exhibited slower growth kinetics (Fig. 7A), as shown previously (Fig. 6A). In addition, CRIM1/VEGFA double-knockdown cells showed a more severe and statistically distinct effect than either single knockdown (Fig. 7A,B, green trace). In similar experiments assessing cell number after 48 hours, we found that the effects of single and combined knockdowns were not compensated by additional exogenous recombinant VEGFA (Fig. 7B). When we assessed growth kinetics for CRIM1 knockdown HUVECs in serum-free, VEGF-deficient medium, we found that the cell number actually decreased (supplementary material Fig. S8A), indicating that some cells die, as might be expected with limited VEGFA and limited alternative survival stimuli. A comparison of the separate or combined effects of VEGFA and CRIM1 knockdown showed that under these conditions, as well, the double knockdown produced the most severe effect (Fig. 7C). An assessment by quantitative PCR of the expression levels of BCL2, a known anti-apoptosis factor, and of BAX, a pro-apoptosis factor, showed that the former exhibited reduced expression whereas the latter exhibited an increase with VEGFA, CRIM1 and combined VEGFA/CRIM1 knockdown (Fig. 7D). This establishes that VEGFA and CRIM1 affect the same target genes in a survival pathway that functions within VECs.

The differential effects of an anti-VEGFA antibody (Avastin) and a VEGFR2 kinase activity inhibitor have been used to show that there is an exclusively autocrine signaling pathway in VECs (Lee et al., 2007). Using VEGFR2 phosphorylation in the presence of orthovanadate in minimal medium as a readout for autocrine signaling activity, we assessed the relative consequences of VEGFA or CRIM1 knockdown and determined whether Avastin or the VEGFR2 kinase activity inhibitor SU5416 could modulate signaling. As already shown, VEGFA or CRIM1 knockdown had very similar consequences for VEGFR2 phosphorylation (Fig. 7E). In addition, we found that Avastin had a very limited ability to suppress VEGFR2 phosphorylation, whereas SU5416 abrogated this completely. Quantitatively, Avastin suppressed VEGFR2 phosphorylation by ∼25%. This means that 75% of the signaling activity can be attributed to an Avastin-resistant, autocrine signaling pathway. Since CRIM1 knockdown can suppress VEGFR2 phosphorylation by significantly more than this, there is a strong argument that, like VEGFA knockdown, CRIM1 knockdown also suppresses autocrine signaling by endogenous VEGFA. This notion is reinforced by the observation that, when CRIM1 and VEGFA knockdown are combined under the same conditions, there is a greater effect than either single knockdown on VEGFR2 phosphorylation (Fig. 7F). Together, these data suggest that CRIM1 regulates the activity of VEGFA within the autocrine pathway known to be active within VECs.

DISCUSSION

We have investigated the function of Crim1 in microvascular development in vivo. Using conditional deletion of a Crim1flox allele, we identified a crucial function for Crim1 in the VECs of the developing retinal vasculature. We also provide evidence that, in VECs, Crim1 regulates autocrine signaling by Vegfa.

Crim1 stabilizes nascent vessel connections

Angiogenic sprouting forms a draft vessel network that subsequently undergoes remodeling to become functional (Potente et al., 2011). Endothelial cell death (Lobov et al., 2005) and retraction of endothelial cells (Chen et al., 2012) can both contribute to vessel regression. In the mouse retina, some segment regression is likely to be triggered by the lack of oxygen demand close to large vessels (Sun et al., 2005), but, in addition, there is sporadic segment regression throughout the forming network. Vessel ghosts, which indicate a regressing segment, can be found even at the advancing front of an angiogenic network and reveal that remodeling is not completely restricted spatially. Disruption of certain molecular pathways, including the Notch pathway (Phng et al., 2009), will cause excessive vessel regression. The current analysis suggests that the transmembrane protein Crim1 has a role in stabilizing newly formed vessel segments; when conditionally mutated in VECs, the consequence is many more vessel ghosts and overall compromise of the forming vascular network.

Does Crim1 regulate cadherin adhesion in the retinal vasculature?

There is evidence that Crim1 can regulate cell-cell adhesion. Crim1 is expressed in adherent cells, especially in those making new cell-cell contacts (Glienke et al., 2002). Crim1 can also form complexes with β-catenin and N-cadherin and, consistent with this, in Xenopus Crim1 stabilizes adhesion junctions and maintains the integrity of neuroepithelium during morphogenesis (Ponferrada et al., 2012). These data suggest that some functions of Crim1 could result from the formation of complexes with VE-cadherin, a cadherin family member known to be crucial for vascular development (Dejana et al., 2009; Strilić et al., 2009). Several features of the Crim1 VEC-specific conditional knockouts also suggested a consequence for adhesion, including: (1) an increase in non-perfusable, VE-cadherin-negative vessel segments; (2) an increase in the bifurcation of tip cells that mimics the behavior of the VE-cadherin knockdown tip cells (Montero-Balaguer et al., 2009); and (3) VECs separated from extending vessels at the angiogenic front, a feature that is also observed in VE-cadherin endothelial conditional mutants (Gaengel et al., 2012), suggesting compromise of stable junctions.

However, there is also evidence countering the suggestion that Crim1 regulates VE-cadherin function. First, when VE-cadherin is depleted from endothelial cells, vessels show excessive branching and overgrowth (Gaengel et al., 2012). This contrasted with Crim1 VEC conditional mutants in which vessel connections with discontinuous VE-cadherin labeling are thin and usually lacking a lining of endothelial cell nuclei (Fig. 3E-H). Second, although we could identify α-catenin and β-catenin in immunoprecipitates of VE-cadherin from cultured confluent endothelial cells, we were not able to identify Crim1, even when we used an epitope-tagged Crim1 to increase detection efficiency (data not shown). These findings suggest that the endothelial cell-cell contact and vessel lumen defects in Crim1 conditional mutants might be an indirect consequence of Crim1 loss of function.

Crim1 regulates autocrine Vegfa signaling

Previous studies on Crim1 in various organisms have suggested that it might regulate the bioavailability of growth factors and morphogens. In vitro studies demonstrate that Crim1 regulates the rate of processing and delivery of Bmp4 and Bmp7 to the cell surface (Wilkinson et al., 2003), probably in the Golgi compartment. Another study has provided evidence that Crim1 can physically bind signaling ligands such as Vegfa, Pgf or Pdgf before their secretion (Wilkinson et al., 2007). In the kidney, Crim1 sequesters Vegfa at the surface of podocytes, so that loss of Crim1 causes excessive Vegfa-Vegfr2 signaling and overgrowth of the glomerular vasculature (Wilkinson et al., 2007). There are also invertebrate homologs of Crim1. The C. elegans homolog of Crim1 (CRM-1) controls body size through regulation of BMP signaling (Fung et al., 2007). Drosophila crimpy, which has sequence homology to Crim1, inhibits Glass bottom boat (a BMP family ligand) in motoneurons during neuromuscular junction development (James and Broihier, 2011). However, in ovo knockdown of CRIM1 in Xenopus and Zebrafish and germline loss of function of Crim1 in mouse do not produce defects in the early patterning of the body axis (Kinna et al., 2006; Chiu et al., 2012; Ponferrada et al., 2012), as would be expected if Crim1 were a key universal regulator of BMP signaling.

Our current findings are consistent with previous analysis of the phenotype after germline deletion of a Crim1 conditional allele (Chiu et al., 2012). When a germline loss-of-function homozygous mutant was produced by recombining our loxP-flanked Crim1 allele with EIIA-Cre, we found an assemblage of changes (including hemorrhage, edema and syndactyly) very similar to the phenotype of the previously characterized insertional (Pennisi et al., 2007) and germline conditional (Chiu et al., 2012) mutants. Although Crim1 mutant mice show hemorrhage, and Crim1 has been implicated in binding Vegfa (Wilkinson et al., 2007), germline Crim1 mutant mice do not show a major failure in early vascular patterning as would be anticipated if Crim1 were a crucial regulator of Vegfa signaling (Carmeliet et al., 1996; Ferrara et al., 1996). Combined, these findings suggest that Crim1 regulates signaling ligands in a temporally and spatially restricted manner.

It has been shown that VECs can produce Vegfa and that this autocrine source of Vegfa is indispensable for blood vessel homeostasis (Lee et al., 2007). The current model suggests that autocrine Vegfa is crucial for stimulating VEC survival in response to stress signals such as hypoxia, irradiation and reactive oxygen species, factors that would be ongoing challenges for mature vessels. The current analysis, in which we have deleted Vegfa in VECs during development, also indicates that autocrine Vegfa is important at developmental stages.

One consequence of VEC-specific Crim1 loss of function is deficient angiogenesis in the retina. Prompted by data showing that Crim1 can regulate Vegfa (Wilkinson et al., 2007) and that Vegfa is the major stimulus for angiogenesis in the retina (Carmeliet and Jain, 2011), we investigated the possibility that the Crim1 phenotype resulted from a Vegfa signaling deficiency. We showed that, in the developing retinal vasculature, Vegfa or Crim1 conditional deletion in VECs gave very similar phenotypes characterized by an increased number of vessel ghosts, discontinuous VE-cadherin labeling and an increase in the number of segments that showed the absence of a vessel lumen. In addition, conditional compound heterozygotes had a phenotype more severe than each single heterozygous conditional mutant and one that was indistinguishable from the homozygous conditional phenotype. The severe phenotype of the double heterozygotes is surprising, and this additive effect is consistent with the hypothesis that this is a synthetic phenotype resulting from the function of Crim1 and Vegfa in the same pathway.

Culture experiments showed directly that CRIM1 regulates autocrine VEGFA signaling. First, we showed, as expected, that proliferation of HUVECs in culture is enhanced by VEGFA supplementation. In addition, we showed that HUVEC expansion is almost absent if we used shRNA targeting CRIM1 even with an exogenous source of VEGFA. Starvation-stimulation experiments with exogenous VEGFA in CRIM1 knockdown HUVECs did not, however, reveal any change in the level of VEGFR2 phosphorylation. This suggested that CRIM1 is required for proliferation and survival in HUVECs, but not because it regulates the activity of exogenous VEGFA. By contrast, when HUVECs were denied exogenous VEGFA and required to rely on autocrine signaling, the outcome for VEGFR2 activation was different. In the absence of exogenous VEGFA, control HUVECs in serum-free medium did not proliferate but survived for 2 days or more. CRIM1 knockdown resulted in a rapid reduction in cell numbers over this timecourse. Accompanying this elevated level of cell death was a reduced proportion of VEGFR2 in its active, phosphorylated state. Evidence that the documented VEGFR2 phosphorylation was a consequence of autocrine signaling came from a comparison of the effects of an anti-VEGFA antibody, which had a very limited effect, and that of a small-molecule VEGFR2 inhibitor, which completely abrogated phosphorylation. Combined, these data support a model in which CRIM1 regulates VEGFA autocrine activity in the previously defined ‘private loop’ (Lee et al., 2007) and is consistent with the observation that Crim1 can form physical complexes with Vegfa (Wilkinson et al., 2007).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Generation of the Crim1 conditional allele

We generated a conditional loss-of-function allele, Crim1flox, using conventional gene targeting. With the very high GC content surrounding exon 1 (5′ UTR and start codon), we targeted exons 3 and 4 (supplementary material Fig. S1A). This design left open the possibility that exons 1 and 2 might produce a functional truncated protein. Incorporation of sequences from the C-terminus of ornithine decarboxylase (cODC) as a signal for rapid degradation (Matsuzawa et al., 2005) was designed to eliminate any expressed CRIM1 N-terminal sequence. The allele design incorporated loxP sites into an artificial exon that is initially in reverse orientation. Through two steps of recombination mediated by a pair of wild-type and a pair of variant loxP sequences that are incompatible, the ODC degradation signal was spliced into the mRNA, simultaneously deleting exons 3 and 4. This allele design strategy has been used previously (Schnütgen et al., 2003).

Mice

Pdgfb-iCreER (Claxton et al., 2008), EIIa-Cre (JAX 003724), Tg(CAG-Bgeo/GFP) (Z/EG, JAX 003920) and the VegfaloxP line (Gerber et al., 1999) have been described previously. To induce endothelial cell gene deletion in Pdgfb-iCreER mouse pups, peanut oil-dissolved tamoxifen (Sigma) was injected intraperitoneally daily at 20 μg/g body weight. Tamoxifen-injected Pdgfb-iCreER-negative littermates were used as controls. Birth was defined as postnatal day (P) 1.

Whole-mount immunofluorescence of retinas

Antibody and isolectin labeling of retinas was performed as previously described (Stefater et al., 2011) with the following: Alexa 488-Isolectin IB4 (Life Technologies, I21411; 1:1000), Crim1 (homemade rabbit antiserum), collagen IV (rabbit; Abcam, ab19808; 1:500), BrdU (mouse; Dako, M0744; 1:100), VE-cadherin (rat; BD Biosciences, 555289; 1:100), VE-cadherin (goat; Santa Cruz, sc-6458; 1:200), CD31 (rat; BD Biosciences, 550274; 1:100), active caspase 3 (rabbit; R&D Systems, AF835; 1:100), podocalyxin (goat; R&D Systems, AF1556; 1:200), PDGFRα (goat; R&D Systems, AF1062; 1:100), desmin (rabbit; Abcam, ab15200; 1:500) and smooth muscle actin (mouse; Sigma, C6198; 1:200).

Cell culture

Pooled HUVECs (Lonza, CC-2519) were cultured on 0.1% gelatin-coated culture dishes in EGM-2 BulletKit medium (Lonza, CC-3162). Cells before passage five were used in all experiments. Lentiviral particles containing shRNA targeting CRIM1 mRNA were acquired from TRC Mission Library (Invitrogen). Cells at 90% confluence were incubated with diluted lentiviral particles together with 8 μg/ml polybrene for 16 hours and then treated with 2 μg/ml puromycin for 2 days to enrich the infected cell population. Twenty-four hours after puromycin removal, cells were used in subsequent experiments. We tested four different shRNAs targeting CRIM1 and chose the two that worked most effectively: TRCN0000063860 [shCRIM1(60)] and TRCN0000063862 [shCRIM1(62)]. Similarly, VEGFA was knocked down using TRCN0000003343, the effectiveness of which has been validated before (Segarra et al., 2012).

Growth curve of HUVECs

HUVECs (5000 cells) expressing scramble shRNA or shRNA targeting CRIM1 or VEGFA were plated in each well of 96-well plates coated with 10 μg/cm2 human fibronectin (Sigma, F2006) and cultured in EGM-2 medium. To monitor cell survival in VEGFA-deficient medium, 20,000 cells (confluent) were plated per well and cultured in EGM-2 without addition of serum or VEGFA.

VEGFR2 activation in cultured HUVECs

To detect the response to exogenous VEGFA, HUVECs expressing shRNAs were starved in EBM-2 (Lonza, CC-2156) containing only antibiotics and heparin for 24 hours and stimulated with recombinant human VEGFA protein (R&D Systems, 293-VE) with 2 mg/ml Na3VO4 for 5 minutes. To detect VEGFR2 activation by autocrine VEGFA, HUVECs expressing shRNAs were cultured in the same medium for 24 hours with or without 0.1 mg/ml Na3VO4. For control experiments, cells were cultured in medium either pre-incubated with 10 μg/ml Avastin (Genentech) or with 0.6 μM SU5416 (Sigma) added. Cell lysates were collected in RIPA buffer containing 2 mg/ml Na3VO4 and the phosphorylated VEGFR2 level detected either by ELISA (Cell Signaling, 7335 and 7340) or immunoblot using antibodies to phospho-VEGFR2 (Y1175, rabbit; Cell Signaling, 2478; 1:500), VEGFR2 (mouse; Santa Cruz, sc-6251; 1:400), CRIM1 (mouse; Sigma, WH0051232M1; 1:500) or α-tubulin (rabbit; Abcam, ab89984; 1:4000).

Quantitative RT-PCR

RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Micro Kit (Qiagen) and cDNA was prepared using Superscript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). Quantitative PCR was performed with iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad). Signals were detected using the Bio-Rad CFX1000 system and gene expression levels were calculated using the standard curve method.

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS)

Freshly isolated mouse retinas were incubated in DMEM (Gibco) containing 1 mg/ml collagenase A (Roche) and 3 U/ml DNase I on a shaker at 37°C for 30 minutes with gentle pipetting every 10 minutes. Cells were passed through cell strainers (BD Biosciences) and centrifuged at 500 g for 5 minutes. After washes in PBS containing 2 mM EDTA and reconstitution in the same buffer, cells were labeled with PE-CD31 and APC-CD45 (Ptprc) antibodies (BD Biosciences) at 4°C for 20 minutes. After washes, cells were reconstituted in PBS containing 2 mM EDTA and passed through a cell strainer again before FACS analysis. PE (CD31)-positive and APC (CD45)-negative populations were sorted and collected as VECs.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Student’s t-test.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Paul Speeg for excellent technical support and Sujata Rao for suggestions on experiments and on the manuscript.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author contributions

J.F., V.G.P., T.S., S.V. and R.A.L. designed the research, performed experiments and analyzed data. J.F. and R.A.L. wrote the paper. M.F., H.G. and N.F. contributed vital reagents.

Funding

We acknowledge grant support from the National Institutes of Health [R01 EY021636]. Deposited in PMC for immediate release.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material available online at http://dev.biologists.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1242/dev.097949/-/DC1

References

- Adini I., Rabinovitz I., Sun J. F., Prendergast G. C., Benjamin L. E. (2003). RhoB controls Akt trafficking and stage-specific survival of endothelial cells during vascular development. Genes Dev. 17, 2721–2732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmeliet P., Jain R. K. (2011). Molecular mechanisms and clinical applications of angiogenesis. Nature 473, 298–307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmeliet P., Ferreira V., Breier G., Pollefeyt S., Kieckens L., Gertsenstein M., Fahrig M., Vandenhoeck A., Harpal K., Eberhardt C., et al. (1996). Abnormal blood vessel development and lethality in embryos lacking a single VEGF allele. Nature 380, 435–439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q., Jiang L., Li C., Hu D., Bu J. W., Cai D., Du J. L. (2012). Haemodynamics-driven developmental pruning of brain vasculature in zebrafish. PLoS Biol. 10, e1001374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu H. S., York J. P., Wilkinson L., Zhang P., Little M. H., Pennisi D. J. (2012). Production of a mouse line with a conditional Crim1 mutant allele. Genesis 50, 711–716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claxton S., Kostourou V., Jadeja S., Chambon P., Hodivala-Dilke K., Fruttiger M. (2008). Efficient, inducible Cre-recombinase activation in vascular endothelium. Genesis 46, 74–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford T. N., Alfaro D. V., III, Kerrison J. B., Jablon E. P. (2009). Diabetic retinopathy and angiogenesis. Curr. Diabetes Rev. 5, 8–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dejana E., Tournier-Lasserve E., Weinstein B. M. (2009). The control of vascular integrity by endothelial cell junctions: molecular basis and pathological implications. Dev. Cell 16, 209–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrara N., Carver-Moore K., Chen H., Dowd M., Lu L., O’Shea K. S., Powell-Braxton L., Hillan K. J., Moore M. W. (1996). Heterozygous embryonic lethality induced by targeted inactivation of the VEGF gene. Nature 380, 439–442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn J. T., Chan-Ling T. (2006). Retinopathy of prematurity: two distinct mechanisms that underlie zone 1 and zone 2 disease. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 142, 46–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fruttiger M. (2007). Development of the retinal vasculature. Angiogenesis 10, 77–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fung W. Y., Fat K. F., Eng C. K., Lau C. K. (2007). crm-1 facilitates BMP signaling to control body size in Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev. Biol. 311, 95–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaengel K., Niaudet C., Hagikura K., Laviña B., Muhl L., Hofmann J. J., Ebarasi L., Nyström S., Rymo S., Chen L. L., et al. (2012). The sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor S1PR1 restricts sprouting angiogenesis by regulating the interplay between VE-cadherin and VEGFR2. Dev. Cell 23, 587–599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasparini G., Longo R., Toi M., Ferrara N. (2005). Angiogenic inhibitors: a new therapeutic strategy in oncology. Nat. Clin. Pract. Oncol. 2, 562–577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerber H. P., McMurtrey A., Kowalski J., Yan M., Keyt B. A., Dixit V., Ferrara N. (1998). Vascular endothelial growth factor regulates endothelial cell survival through the phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase/Akt signal transduction pathway. Requirement for Flk-1/KDR activation. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 30336–30343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerber H. P., Hillan K. J., Ryan A. M., Kowalski J., Keller G. A., Rangell L., Wright B. D., Radtke F., Aguet M., Ferrara N. (1999). VEGF is required for growth and survival in neonatal mice. Development 126, 1149–1159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerhardt H., Betsholtz C. (2003). Endothelial-pericyte interactions in angiogenesis. Cell Tissue Res. 314, 15–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerhardt H., Golding M., Fruttiger M., Ruhrberg C., Lundkvist A., Abramsson A., Jeltsch M., Mitchell C., Alitalo K., Shima D., et al. (2003). VEGF guides angiogenic sprouting utilizing endothelial tip cell filopodia. J. Cell Biol. 161, 1163–1177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geudens I., Gerhardt H. (2011). Coordinating cell behaviour during blood vessel formation. Development 138, 4569–4583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glienke J., Sturz A., Menrad A., Thierauch K. H. (2002). CRIM1 is involved in endothelial cell capillary formation in vitro and is expressed in blood vessels in vivo. Mech. Dev. 119, 165–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellström M., Phng L. K., Hofmann J. J., Wallgard E., Coultas L., Lindblom P., Alva J., Nilsson A. K., Karlsson L., Gaiano N., et al. (2007). Dll4 signalling through Notch1 regulates formation of tip cells during angiogenesis. Nature 445, 776–780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoelzle M. K., Svitkina T. (2012). The cytoskeletal mechanisms of cell-cell junction formation in endothelial cells. Mol. Biol. Cell 23, 310–323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jager R. D., Mieler W. F., Miller J. W. (2008). Age-related macular degeneration. N. Engl. J. Med. 358, 2606–2617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James R. E., Broihier H. T. (2011). Crimpy inhibits the BMP homolog Gbb in motoneurons to enable proper growth control at the Drosophila neuromuscular junction. Development 138, 3273–3286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinna G., Kolle G., Carter A., Key B., Lieschke G. J., Perkins A., Little M. H. (2006). Knockdown of zebrafish crim1 results in a bent tail phenotype with defects in somite and vascular development. Mech. Dev. 123, 277–287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolle G., Jansen A., Yamada T., Little M. (2003). In ovo electroporation of Crim1 in the developing chick spinal cord. Dev. Dyn. 226, 107–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolle G., Georgas K., Holmes G. P., Little M. H., Yamada T. (2000). CRIM1, a novel gene encoding a cysteine-rich repeat protein, is developmentally regulated and implicated in vertebrate CNS development and organogenesis. Mech. Dev. 90, 181–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larrivée B., Prahst C., Gordon E., del Toro R., Mathivet T., Duarte A., Simons M., Eichmann A. (2012). ALK1 signaling inhibits angiogenesis by cooperating with the Notch pathway. Dev. Cell 22, 489–500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S., Chen T. T., Barber C. L., Jordan M. C., Murdock J., Desai S., Ferrara N., Nagy A., Roos K. P., Iruela-Arispe M. L. (2007). Autocrine VEGF signaling is required for vascular homeostasis. Cell 130, 691–703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobov I. B., Rao S., Carroll T. J., Vallance J. E., Ito M., Ondr J. K., Kurup S., Glass D. A., Patel M. S., Shu W., et al. (2005). WNT7b mediates macrophage-induced programmed cell death in patterning of the vasculature. Nature 437, 417–421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovicu F. J., Kolle G., Yamada T., Little M. H., McAvoy J. W. (2000). Expression of Crim1 during murine ocular development. Mech. Dev. 94, 261–265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzawa S., Cuddy M., Fukushima T., Reed J. C. (2005). Method for targeting protein destruction by using a ubiquitin-independent, proteasome-mediated degradation pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 14982–14987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montero-Balaguer M., Swirsding K., Orsenigo F., Cotelli F., Mione M., Dejana E. (2009). Stable vascular connections and remodeling require full expression of VE-cadherin in zebrafish embryos. PLoS ONE 4, e5772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namiki A., Brogi E., Kearney M., Kim E. A., Wu T., Couffinhal T., Varticovski L., Isner J. M. (1995). Hypoxia induces vascular endothelial growth factor in cultured human endothelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 31189–31195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennisi D. J., Wilkinson L., Kolle G., Sohaskey M. L., Gillinder K., Piper M. J., McAvoy J. W., Lovicu F. J., Little M. H. (2007). Crim1KST264/KST264 mice display a disruption of the Crim1 gene resulting in perinatal lethality with defects in multiple organ systems. Dev. Dyn. 236, 502–511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phng L. K., Gerhardt H. (2009). Angiogenesis: a team effort coordinated by notch. Dev. Cell 16, 196–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phng L. K., Potente M., Leslie J. D., Babbage J., Nyqvist D., Lobov I., Ondr J. K., Rao S., Lang R. A., Thurston G., et al. (2009). Nrarp coordinates endothelial Notch and Wnt signaling to control vessel density in angiogenesis. Dev. Cell 16, 70–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponferrada V. G., Fan J., Vallance J. E., Hu S., Mamedova A., Rankin S. A., Kofron M., Zorn A. M., Hegde R. S., Lang R. A. (2012). CRIM1 complexes with β-catenin and cadherins, stabilizes cell-cell junctions and is critical for neural morphogenesis. PLoS ONE 7, e32635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potente M., Gerhardt H., Carmeliet P. (2011). Basic and therapeutic aspects of angiogenesis. Cell 146, 873–887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao S., Chun C., Fan J., Kofron J. M., Yang M. B., Hegde R. S., Ferrara N., Copenhagen D. R., Lang R. A. (2013). A direct and melanopsin-dependent fetal light response regulates mouse eye development. Nature 494, 243–246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnütgen F., Doerflinger N., Calléja C., Wendling O., Chambon P., Ghyselinck N. B. (2003). A directional strategy for monitoring Cre-mediated recombination at the cellular level in the mouse. Nat. Biotechnol. 21, 562–565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segarra M., Ohnuki H., Maric D., Salvucci O., Hou X., Kumar A., Li X., Tosato G. (2012). Semaphorin 6A regulates angiogenesis by modulating VEGF signaling. Blood 120, 4104–4115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibuya M. (2001). Structure and dual function of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1 (Flt-1). Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 33, 409–420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefater J. A., III, Lewkowich I., Rao S., Mariggi G., Carpenter A. C., Burr A. R., Fan J., Ajima R., Molkentin J. D., Williams B. O., et al. (2011). Regulation of angiogenesis by a non-canonical Wnt-Flt1 pathway in myeloid cells. Nature 474, 511–515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenzel D., Lundkvist A., Sauvaget D., Busse M., Graupera M., van der Flier A., Wijelath E. S., Murray J., Sobel M., Costell M., et al. (2011). Integrin-dependent and -independent functions of astrocytic fibronectin in retinal angiogenesis. Development 138, 4451–4463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strilić B., Kucera T., Eglinger J., Hughes M. R., McNagny K. M., Tsukita S., Dejana E., Ferrara N., Lammert E. (2009). The molecular basis of vascular lumen formation in the developing mouse aorta. Dev. Cell 17, 505–515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J. F., Phung T., Shiojima I., Felske T., Upalakalin J. N., Feng D., Kornaga T., Dor T., Dvorak A. M., Walsh K., et al. (2005). Microvascular patterning is controlled by fine-tuning the Akt signal. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 128–133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tammela T., Zarkada G., Nurmi H., Jakobsson L., Heinolainen K., Tvorogov D., Zheng W., Franco C. A., Murtomäki A., Aranda E., et al. (2011). VEGFR-3 controls tip to stalk conversion at vessel fusion sites by reinforcing Notch signalling. Nat. Cell Biol. 13, 1202–1213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson L., Kolle G., Wen D., Piper M., Scott J., Little M. (2003). CRIM1 regulates the rate of processing and delivery of bone morphogenetic proteins to the cell surface. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 34181–34188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson L., Gilbert T., Kinna G., Ruta L. A., Pennisi D., Kett M., Little M. H. (2007). Crim1KST264/KST264 mice implicate Crim1 in the regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor-A activity during glomerular vascular development. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 18, 1697–1708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson L., Gilbert T., Sipos A., Toma I., Pennisi D. J., Peti-Peterdi J., Little M. H. (2009). Loss of renal microvascular integrity in postnatal Crim1 hypomorphic transgenic mice. Kidney Int. 76, 1161–1171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.