Abstract

Neutrophil recruitment from blood to extravascular sites of sterile or infectious tissue damage is a hallmark of early innate immune responses, and the molecular events leading to cell exit from the bloodstream have been well defined1,2. Once outside the vessel, individual neutrophils often show extremely coordinated chemotaxis and cluster formation reminiscent of the swarming behaviour of insects3–11. The molecular players that direct this response at the single-cell and population levels within the complexity of an inflamed tissue are unknown. Using two-photon intravital microscopy in mouse models of sterile injury and infection, we show a critical role for intercellular signal relay among neutrophils mediated by the lipid leukotriene B4, which acutely amplifies local cell death signals to enhance the radius of highly directed interstitial neutrophil recruitment. Integrin receptors are dispensable for long-distance migration12, but have a previously unappreciated role in maintaining dense cellular clusters when congregating neutrophils rearrange the collagenous fibre network of the dermis to form a collagen-free zone at the wound centre. In this newly formed environment, integrins, in concert with neutrophil-derived leukotriene B4 and other chemoattractants, promote local neutrophil interaction while forming a tight wound seal. This wound seal has borders that cease to grow in kinetic concert with late recruitment of monocytes and macrophages at the edge of the displaced collagen fibres. Together, these data provide an initial molecular map of the factors that contribute to neutrophil swarming in the extravascular space of a damaged tissue. They reveal how local events are propagated over large-range distances, and how auto-signalling produces coordinated, self-organized neutrophil-swarming behaviour that isolates the wound or infectious site from surrounding viable tissue.

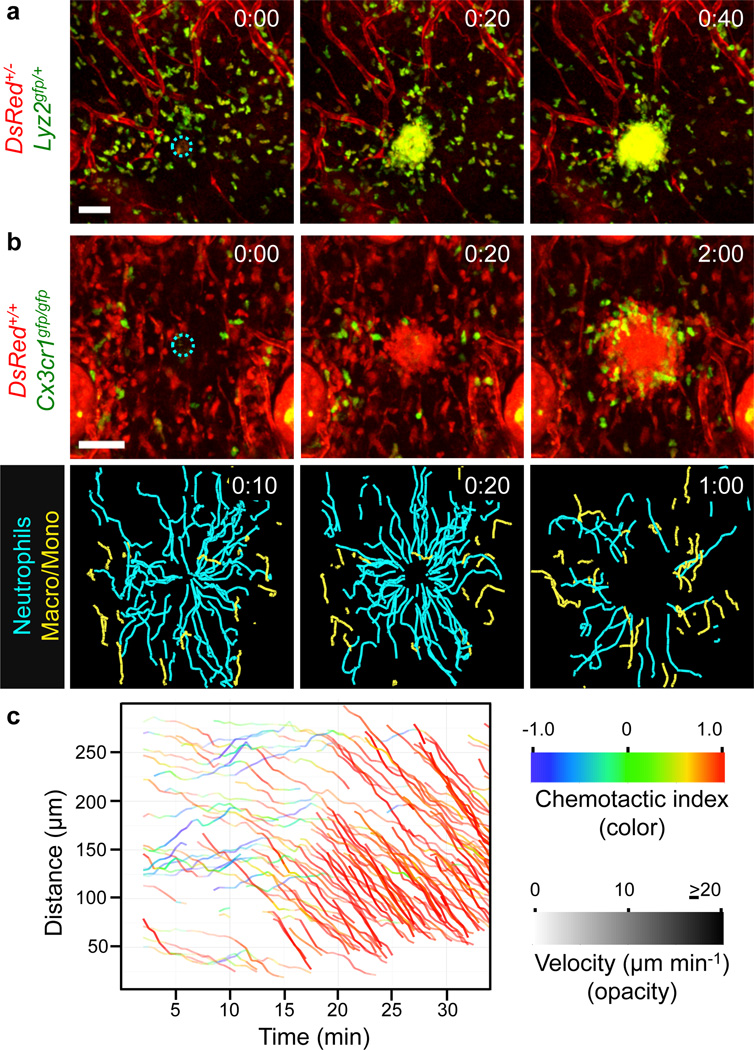

Neutrophil swarming has been observed using intravital microscopy in inflamed, infected or sterilely wounded tissues3–11,13, and a series of sequential phases have been described3,4: (1) initial chemotaxis of individual neutrophils close to the damage, followed by (2) amplified chemotaxis of neutrophils from more distant interstitial regions, leading to (3) neutrophil clustering. To study the molecules controlling these distinct neutrophil-response phases, we used an inducible model of sterile skin injury in which a brief intense two-photon laser pulse causes focal, dermis-restricted tissue damage (Supplementary Fig. 2)4. We were specifically interested in how neutrophils coordinate swarming in the extravascular space, so we performed two-photon intravital microscopy (2P-IVM) of neutrophils that had already exited blood vessels and entered a mildly inflamed dermis before laser damage. Focal injury induced substantial interstitial chemotaxis of lysozyme 2–green fluorescent protein (Lyz2–GFP, also known as LysM–GFP)-positive neutrophils/monocytes that lasted ~25–40 min before cells accumulated in a cluster at the damage site and recruitment stopped (Fig. 1a). The dynamic behaviour of neutrophils differed from CX3CR1-positive macrophages/monocytes in the same environment, with neutrophils immediately showing highly directed chemotaxis towards the wound centre at high speeds (10–20 µm min−) and the CX3CR1-positive cells migrating at slower speeds (3–5 µm min−) and undergoing a chemotactic response only after an initial neutrophil cluster had formed. In contrast to neutrophils, macrophages/monocytes never entered the developing cell cluster, but assembled around it during cessation of the neutrophil swarm growth (Fig. 1b, Supplementary Fig. 3a and Supplementary Video 1). As reported previously, the early dynamics of endogenous neutrophils were biphasic (Supplementary Fig. 3b) and similar for neutrophils that were isolated from mouse bone marrow (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Video 2) or human peripheral blood (Supplementary Fig. 3c) and then injected into the dermis. In 79% of the experiments (169 out of 213), a first phase (1–15 min) of initial neutrophil chemotaxis close to the damage was followed by a dramatic second phase of substantial neutrophil recruitment from distant sites involving markedly increased directionality and speed (Fig. 1c). We noticed the appearance of cell fragments around developing neutrophil clusters, suggesting that cell death could lead to release of components driving neutrophil swarming14. Using propidium iodide, we detected a clear kinetic correlation between the death of a few neutrophils at the damage site and the onset of the amplified second phase of neutrophil recruitment (Fig. 2a, Supplementary Figs 4 and 5a and Supplementary Video 3). Most of the neutrophils in the developing cell cluster remained viable (Supplementary Fig. 5b), suggesting that the death of only a small number of neutrophils was sufficient to drive the substantial chemotactic response of the neutrophil population.

Figure 1. Neutrophil extravascular swarming dynamics.

2P-IVM on intact ear dermis of anesthetized mice. Interstitial cell recruitment towards focal damage (blue dotted circle) was recorded. a, b, Time-lapse sequence of endogenous innate immune cell dynamics in DsRed+/−Lyz2gfp/+Tyrc-2J/c-2J mice (myelomonocytic cells in green-yellow, stroma in red) (a) and DsRed+/+Cx3cr1gfp/gfp Tyrc-2J/c-2J mice (macrophages/monocytes in green, neutrophils and stroma in red). Cell tracks over the last 10 min (n=4) (b, bottom). Scale bars, 50 µm. Time, h:min. c, Distance-time plot (DTP) of intradermal (i.d.) injected bone marrow neutrophils; individual cell-migration paths towards the damage site are each highlighted with instantaneous chemotactic index (colour) and velocity (opacity). Representative experiment of n=169.

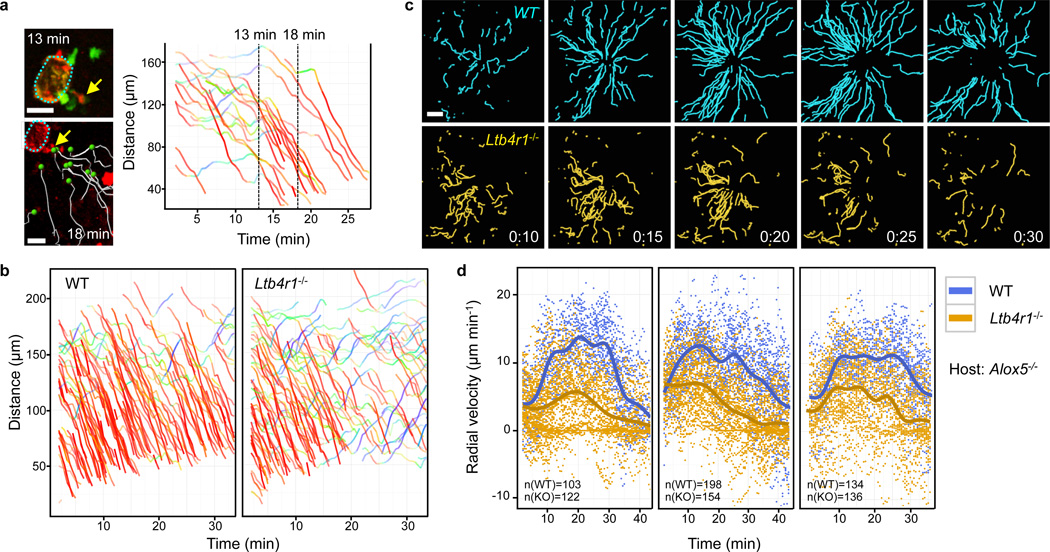

Figure 2. LTB4 promotes neutrophil recruitment from distant sites.

a, 2P-IVM images of a single neutrophil becoming propidium iodide-positive (arrow) at 13 min and its correlation to neutrophil-amplified chemotaxis (white tracks). DTP analysis for migration paths coloured as in Fig. 1. b, Comparative analysis of interstitial recruitment after i.d. co-injection of Ltb4r1−/− and wild-type (WT) neutrophils into Tyrc-2J/c-2J mice. DTP of one representative experiment (n=8). c, Time-course of migration tracks towards 10 µm-damage. Time, h:min. Scale bars, 20 µm (a), 50 µm (c). Track durations, 5 min (a), 10 min (c). d, Comparative analysis of interstitial recruitment after i.d. co-injection of Ltb4r1−/− knockout (KO) and wild-type neutrophils into Alox5−/− Tyrc-2J/c-2J mice. Radial velocity-time plots with regression lines showing the recruitment dynamics for three individual experiments (of n=7). n (in graph) indicates the number of analyzed tracks. Each dot represents the instantaneous radial velocity for one cell at that time point.

Although neutrophil death appeared to serve as a catalyst for swarming, it was unclear how such a signal would propagate through the structurally dense tissue in just a few minutes to initiate acute chemotaxis of neutrophils at sites more than 300 µm away from the core lesion, and also maintain directional migration for ~25–40 min. To investigate the nature of this signal, we performed intradermal co-injection experiments with control and gene-deficient neutrophils and imaged them side by side in the same tissue volume in each experiment. The experimental set-up eliminated problematic quantitative comparisons based on measurements of wild-type and mutant cells imaged in different experiments that can be influenced by varying tissue composition in the imaging volume (Supplementary Fig. 6). More importantly, this protocol bypassed the extravasation step, which allowed for the study of neutrophils depleted of molecules essential for vessel exit.

Neutrophils express more than 30 cell-surface receptors for various attractants, which upon activation and signalling rearrange the cyto-skeleton to yield a functionally polarized neutrophil that is poised for directed migration15,16. In these cells, most G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) act through the predominantly expressed Gαi isoforms Gαi2 and Gαi3. We found that only neutrophils genetically lacking Gαi2 (Gnai2−/−), but not Gαi3 (Gnai3−/−), show impaired interstitial chemotaxis (Supplementary Fig. 7)17. As Gαi2 couples to several neutrophil GPCRs, we next investigated the function of individual GPCRs. Most knockouts for single receptor genes tested (Fpr1, Fpr2, Cxcr2, Supplementary Fig. 8 and Supplementary Video 4; C5ar1, Ccr1, Ccr2, Ccr5, Cxcr6, Ptafr, P2ry2, data not shown)—many of which have been previously reported to have important roles in inflammatory, infectious or autoimmune conditions (Supplementary Information)— showed normal interstitial chemotaxis, indicating that their respective ligands are not uniquely involved in the recruitment phase of the swarming response. Similarly, migration of neutrophils lacking receptors that detect the presence of danger signals (Myd88, Il1r1, Tnfrsf1a and Il1r1, P2rx7) was normal (data not shown). However, neutrophils lacking the high-affinity receptor for leukotriene B4 (LTB4) showed a uniquely impaired swarming response. During early phases (<15 min), Ltb4r1−/− neutrophils close to the damage site still performed chemotaxis towards the wound, whereas cells from more distant sites were only poorly recruited (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Fig. 9a and Supplementary Video 5), a phenotype that became even more striking when the damage size was smaller (Fig. 2c, Supplementary Fig. 10 and Supplementary Video 6). This reduction in neutrophil recruitment was mainly due to impaired chemotaxis rather than chemokinesis, and was most obvious during the late phases of the swarming response (>15 min) (Supplementary Fig. 9b).

In inflamed tissues, LTB4 can originate from several cellular sources. Earlier studies implicated a role for neutrophil-derived LTB4 in the initial stages of neutrophil recruitment from blood into inflamed tissues and disease progression18–22. To examine whether neutrophils auto-amplified the swarming response through LTB4 production and signalling, we performed injection studies into 5-lipoxygenase-deficient mice (Alox5−/−) that cannot synthesize leukotrienes, such that only injected neutrophils could act as an LTB4 source. When co-injected with control cells, Ltb4r1−/− neutrophils again showed impaired interstitial chemotaxis and recruitment from distant sites (Fig. 2d, Supplementary Fig. 11 and Supplementary Video 7). When LTB4-secreting wild-type neutrophils were injected alone, they migrated to the injury from distances >200 µm and formed large clusters. By contrast, when we injected Alox5−/− neutrophils alone into Alox5−/− hosts so that no leukotrienes were present, only neutrophils close to the damage site (< 100 µm) were transiently recruited, resulting in small neutrophil clusters (Supplementary Fig. 12). Although these experiments establish an important role for neutrophil-derived LTB4 in recruiting neutrophils from distant sites in a feed-forward manner, they also show the existence of short-range chemotactic signals from the initial tissue injury and/or locally dying cells, as even in the absence of leukotrienes small clusters can form. We conclude that several of these initial primary factors not only act as short-range chemotactic signals, but also induce LTB4 secretion in neutrophils to acutely enhance the radius of neutrophil recruitment (Supplementary Fig. 1, panels 1–4), consistent with previous data on multiple LTB4-inducing factors22–25. This model is in agreement with earlier in vitro studies showing that primary signals induced secretion of LTB4 that acts as a signal relay molecule to improve chemotaxis of a whole neutrophil population23.

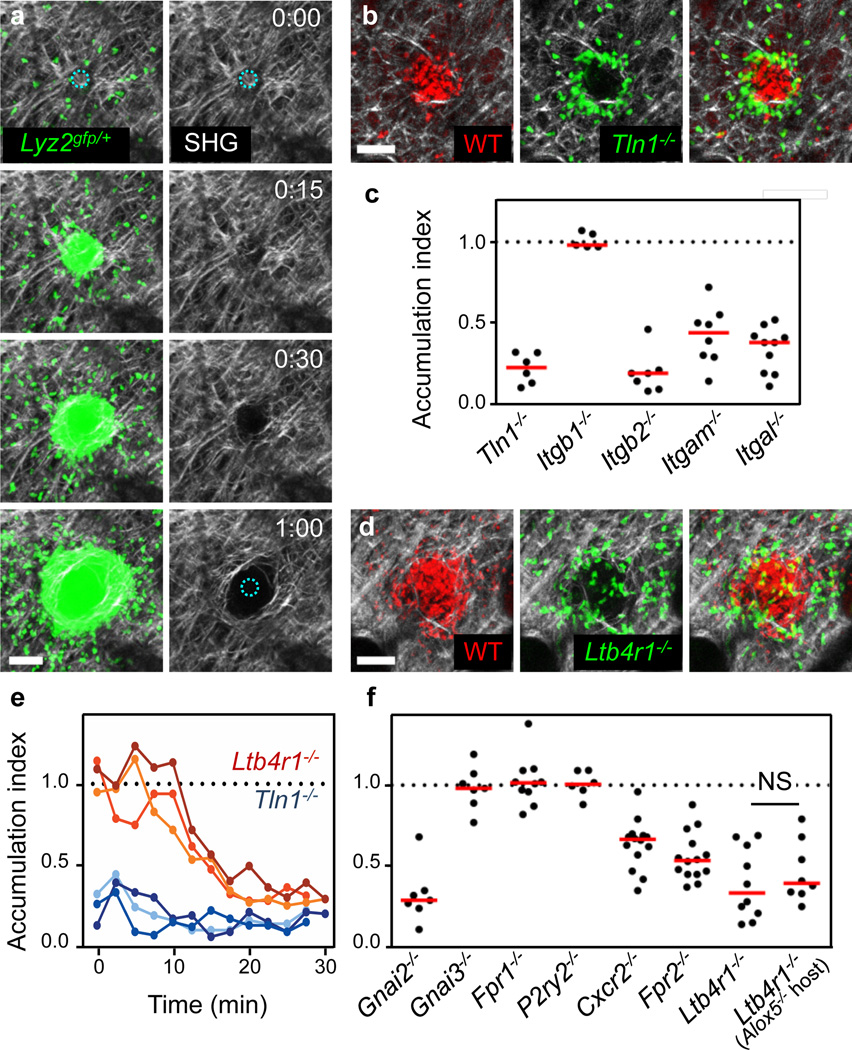

Because LTB4 not only induces intracellular polarity to direct chemotaxis, but can also regulate neutrophil adhesiveness by activating integrin receptors26,27, we next targeted integrin functionality by injecting neutrophils deficient for talin (Tln1−/−). Talin interaction with integrin cytoplasmic domains is crucial for integrin activation, substrate binding and coupling of filamentous actin to adhesion sites28. Because interstitial chemotaxis of Tln1−/− cells was unimpaired (Supplementary Fig. 13 and Supplementary Video 8), high-affinity integrin function was dispensable for neutrophil interstitial migration in vivo, thus confirming earlier studies with dendritic cells in skin explants12. Together, our results demonstrate that LTB4 has a non-redundant role in directing tissue-migrating neutrophils to sites of tissue injury by activating chemotaxis signal pathways.

We next sought to analyse the subsequent step of swarming when neutrophils accumulate and form substantial cell clusters. Visualization of the dense dermal collagen network using the second harmonic generation signal showed clearance of visible fibres from the core of the wound where the densest clustering occurred (Fig. 3a), an effect that was not due to thermal damage (Supplementary Fig. 14a, b). Congregating neutrophils appeared to physically exclude collagen fibres from the core of the cell infiltrate (Supplementary Video 9), although some limited proteolysis of extracellular matrix structures cannot be ruled out. Notably, monocytes always aligned along collagen fibres at the outer edges of the cell cluster, suggesting that neutrophils are specifically adapted to enter the collagen-free centre (Supplementary Fig. 14c). When we visualized both endogenous neutrophils and the cellular actin cortex of injected Lifeact–GFP+/− neutrophils in the collagen-free wound core, we could clearly observe neutrophils migrating in contact with each other with motion paths and focal filamentous actin accumulations that were suggestive of adhesive interactions (Supplementary Video 10). Indeed, when Tln1−/− or Itgb2−/− (β2 integrin-deficient) neutrophils were co-injected with control cells, they showed a striking phenotype, as they were completely unable to enter the collagen-free zone and accumulated at the edge of the wild-type neutrophil cluster (Fig. 3b, c and Supplementary Videos 11, 12). Deficiency in either LFA-1 (Itgal−/−) or Mac-1 (Itgam−/−) had a measurable effect on central accumulation, suggesting that both were involved in cell adhesion and movement within the collagen-free zone (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Fig. 15a). These unexpected findings indicate that high-affinity integrins are critical for neutrophil accumulation in the collagen-free wound centre, which fundamentally differs in its extracellular architecture from the surrounding intact dermal interstitium where leukocyte migration does not require high-affinity integrin function.

Figure 3. Integrin and GPCR signaling at the neutrophil cluster.

a, After focal damage (blue dotted circle), congregating neutrophils rearrange collagenous fibers (visualized by collagen second harmonic generation, SHG). Time, h:min. Scale bar, 50 µm. b–f, Comparative analysis of neutrophil clustering after i.d. co-injection of gene-deficient and wild-type neutrophils into Tyrc-2J/c-2J or Alox5−/− Tyrc-2J/c-2J mice. b, d, 2P-IVM images at the endpoint of the clustering response. Scale bars, 50 µm. c, f, Accumulation index as quantitative parameter for neutrophil entry into the collagen-free wound center. Each dot represents analysis of one damage site. Median in red. ns, non-significant (Mann Whitney U-test). (e) Time-course of neutrophil accumulation in the wound center. Three representative experiments are presented for each gene-deficiency.

We next examined the role of GPCR signals in regulating neutrophil aggregation at the wound. Gnai2−/− neutrophils were excluded from the central neutrophil cluster over time, whereas Gnai3−/− accumulated normally (Supplementary Fig. 15b and Supplementary Video 13). When investigating individual GPCRs, we detected impaired aggregation for neutrophils lacking CXCR2, FPR2 or LTB4R1, with the latter showing the strongest impact on the aggregation response (Fig. 3d, f and Supplementary Video 14; other tested GPCR or receptors had no effect, Supplementary Fig. 15). In contrast to adhesion-deficient Tln1−/− cells, Ltb4r1−/− neutrophils were intermixed with wild-type cells at the earliest aggregation stages. Over time, however, Ltb4r1−/− neutrophils were excluded from the growing cluster (Fig. 3e and Supplementary Fig. 16a). Similar results were obtained when Ltb4r1−/− and wild-type neutrophils were injected into Alox5−/− hosts (Fig. 3f and Supplementary Video 14), indicating that neutrophils secrete LTB4 to regulate clustering in a feed-forward manner. Detection of ligands for other cluster-mediating receptors, such as CXCL2 for CXCR2 and CRAMP for FPR2, in accumulating neutrophils (Supplementary Fig. 16b) suggests that signalling through multiple GPCR, especially LTB4R1, may act to increase neutrophil aggregation to maintain tight association and motility for continued uptake of cellular wound debris or potential pathogens in the cellular cluster (Supplementary Fig. 1, panels 5–8).

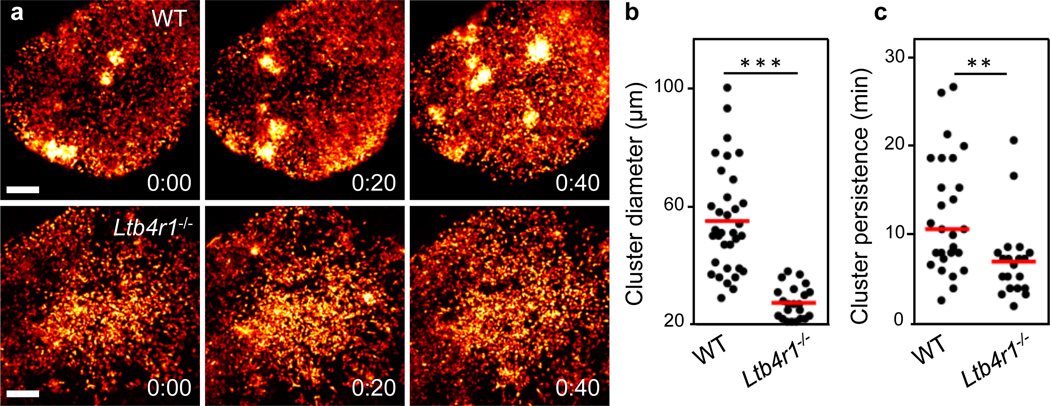

Our findings thus identify a crucial dual function for LTB4 in both the recruitment and the clustering phases of the swarm response to sterile injury. To test the relevance of these findings in an infectious situation, we investigated the role of LTB4 during transient neutrophil swarming in infected lymph nodes3. We have shown previously that Pseudomonas aeruginosa induces cell death of subcapsular macrophages, which subsequently leads to neutrophil recruitment to the lymph node29. Whereas endogenous neutrophils in control mice formed several large but transient cell clusters and were highly chemotactic between the competing transient clusters, Ltb4r1−/− neutrophils were slower and formed only very small, if any, clusters (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Video 15). Consequently, neutrophil cluster diameter and persistence were significantly lower in the absence of LTB4 signalling (Fig. 4b, c), thus confirming the results of the controlled inducible model of focal laser skin injury and extending them to other tissues, forms of cell death and infectious conditions.

Figure 4. LTB4 requirement for swarming in infected lymph nodes.

Mice were infected with P. aeruginosa-GFP in the footpad of mice and 2P-IVM was then performed on the draining popliteal lymph nodes at the time indicated. a, Time-lapse sequence of infected subcapsular sinuses of wild-type Lyz2gfp/+ (top) and Ltb4r1−/−Lyz2gfp/+ (bottom) mice. Analysis was performed when comparable neutrophil numbers were in the sinus (wild-type: 3 h, Ltb4r1−/−: 4.5 h). Neutrophil-GFP signal is pseudo-coloured (heat map) to indicate neutrophil clusters (white). Time, h:min. Scale bars, 100 µm. b, c, Quantification of cluster diameter (b) and persistence (c), data pooled from three independent experiments. b, ***: P<0.001 (Student’s t-test), c, **: P<0.01 (Mann-Whitney U-test). Red bars, mean (b), median (c).

The chemoattractants that direct the neutrophil tissue response can stem from the injured tissue, resident cells, recruited blood-derived leukocytes and potential pathogens. The specific mixture of these various signals will determine the neutrophil chemotactic response at each inflammatory or infectious site. In large sterile liver injuries, integrin-dependent intravascular neutrophil migration requires CXCR2 ligands on liver sinusoids and formyl peptides in the injury zone13. Here we have investigated extravascular neutrophil swarming at very small focal sites of sterile tissue injury in the skin (~1,000× smaller than those examined in the liver model)4 and in infected lymph nodes3. We found that local cell death initiates dramatic swarm-like interstitial neutrophil recruitment and clustering, with a key role for LTB4 as a unique intercellular communication signal between neutrophils that allows rapid integrin-independent neutrophil recruitment through the tissue. Such insights should prove useful for studies in which local sterile or pathogen-induced cell death characterizes innate immune cell dynamics3–11, and the molecules identified may serve as potential targets for therapeutic intervention in destructive neutrophil-dependent inflammatory processes.

FULL METHODS

Mice

Supplementary Table 1 lists all mouse strains and crosses used in this study. Gnai2−/− 30, Gnai3−/− 31, Itgb1fl/fl 32, Tln1fl/fl 33, Ccr1−/− 34, Fpr1−/− 35, Fpr2−/− 36, Ptafr−/− 37, Myd88−/− 38 and Lifeact–GFP+/− 39 mice have been described elsewhere. Lyz2gfp/gfp40 and Il1r1−/− 41 mice were obtained from Taconic Laboratories through a special contract with the NIAID. All other mouse strains were purchased from Jackson Laboratories. All mice were maintained in specific-pathogen-free conditions at an Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care-accredited animal facility at the NIAID and were used under a study protocol approved by NIAID Animal Care and Use Committee (National Institutes of Health).

2P-IVM of ear skin and infected lymph nodes

Two-photon intravital imaging of ear pinnae of anaesthetized mice was performed as previously described5,42. Mice were anaesthetized using isoflurane (Baxter; 2% for induction, 1–1.5% for maintenance, vaporized in an 80:20 mixture of oxygen and air) and placed in a lateral recumbent position on a custom imaging platform such that the ventral side of the ear pinna rested on a coverslip. A strip of Durapore tape was placed lightly over the ear pinna and affixed to the imaging platform to immobilize the tissue. Care was taken to minimize pressure on the ear. Images were captured towards the anterior half of the ear pinna where hair follicles are sparse. Images were acquired using an inverted LSM 510 NLO multiphoton microscope (Carl Zeiss Microimaging) enclosed in a custom-built environmental chamber that was maintained at 32 °C using heated air. This system had been custom fitted with three external non-descanned photomultiplier tube detectors in the reflected light path. Images were acquired using a 25x/0.8 numerical aperture (NA) Plan-Apochromat objective (Carl Zeiss Imaging) with glycerol as immersion medium. Fluorescence excitation was provided by a Chameleon XR Ti:Sapphire laser (Coherent) tuned to 850nm for dye excitation and generation of collagen second harmonic signal, or 920 nm for enhanced GFP (eGFP) excitation and 940 nm for excitation of both DsRed and eGFP. For four-dimensional data sets, three-dimensional stacks were captured every 30 s, unless otherwise specified. All imaged mice were on the Tyrc-2J/c-2J (B6.Albino) background to avoid laser-induced cell death of light-sensitive skin melanophages43. 2P-IVM on P. aeruginosa-infected lymph nodes was performed as previously described29. 107 colony-forming units of GFP-expressing Pseudomonas aeruginosa44 (provided by M. Parsek) were diluted in PBS and injected in the footpad (30µl) of wild-type Lyz2gfp/+ and Ltb4r1−/− Lyz2gfp/+ mice and draining lymph nodes imaged at indicated times after infection using a Zeiss 710 microscope equipped with a Chameleon laser (Coherent) and a 20x water-dipping lens (NA 1.0, Zeiss). The microscope was enclosed in an environmental chamber in which anaesthetized mice were warmed by heated air, and the surgically exposed lymph node was kept at 36–37 °C with warmed PBS. For 2P-IVM of the subcapsular sinus, we used a z-stack of 40–50 µm, 3-µm step size and acquired images every 40 s. Raw imaging data were processed with Imaris (Bitplane) using a Gaussian filter for noise reduction. All images and movies are displayed as two-dimensional maximum-intensity projections of 10–30-µm-thick z-stacks.

Endogenous mouse innate immune cells

For the study of endogenous innate immune cells in the extravascular space, transgenic reporter mice were crossed with Tyrc-2J/c-2J (B6.Albino) mice to yield Lyz2gfp/+Tyrc-2J/c-2J (myelomonocytic cells), DsRed+/−Lyz2gfp/+ Tyrc-2J/c-2J (myelomonocytic cells, stroma) and DsRed+/+ Cx3cr1gfp/gfp Tyrc-2J/c-2J (macrophages/monocytes, stroma and neutrophils) mice. These animals were anaesthetized with isoflurane and underwent a brief skin trauma to recruit neutrophils from the circulation to the dermal interstitium. The anaesthetized mouse was placed on a scale and 30 N per cm2 pressure was applied for 15–20 s on the mouse ear with the investigator’s thumb. As this method induced initial neutrophil extravasation that stopped after 2–3 h, this method was superior to other tested common inflammatory treatments (for example, chemical skin irritation) that all lead to neutrophil recruitment from blood over longer time periods. Three hours after brief skin trauma, mice were prepared for skin imaging as described above and rested in the heated environmental chamber for 30–60 min before the first focal tissue damage was induced.

Neutrophil isolation, labelling and i.d. injection

For i.d. injection experiments, mouse neutrophils were isolated from bone marrow using a three-layer Percoll gradient of 78%, 69% and 52% as previously described45. Neutrophils were collected at the 69–78% interface and were highly purified (>98%) as indicated by Lyz2– eGFPhi Ly6Gpos Ly6Cneg phenotype in flow cytometry46 (data not shown), with viability >98% by trypan blue staining. Neutrophils were washed three times with washing buffer (1× Hank’s balanced salt solution, 1% FBS, 2mM EDTA). If further labelled with cell dyes, neutrophils were incubated for 15 min with either 0.8 µM cell tracker red (CMTPX) or 1 µM cell tracker green (CMFDA) in 1× HBSS supplemented with 0.0002% (w/v) pluronic F-127 (all Life Technologies). Neutrophils were washed four times with washing buffer, before a 1:1 ratio of differentially labelled control and gene-deficient neutrophils (each >2× 106 cells) was taken up in 1× PBS at a volume of 15–30 µl. A volume of 5 µl neutrophil suspension was injected intradermally with an insulin syringe (31.5 GA needle, BD Biosciences) into the ventral side of the mouse ear pinnae. Recipient mice were always on the Tyrc-2J/c-2J (B6.Albino) background. Two hours after injection, mice were prepared for skin imaging as described above and rested in the heated environmental chamber for 30–60 min before the first focal tissue damage was induced. For isolation of talin-deficient neutrophils, Tln1fl/fl mice were intercrossed with Mx1-cre+/− mice47 to yield Tln1fl/fl Mx1-cre+/−. In these mice, Cre expression in the haematopoietic system was induced by intraperitoneal injection of 250 µg Poly(I):Poly(C) (Amersham Biosciences). Five days after knockout induction neutrophils were isolated from bone marrow with high efficiency of talin depletion12. For most injection experiments, we interchanged dyes to exclude unspecific effects and never observed differences in migration or accumulation phenotypes. Whereas cell tracker green labels neutrophils homogeneously, cell tracker red gives a polarized neutrophil staining over time. Cell tracker red also leaks over time from cells, resulting in background fluorescence in the tissue and some fluorescent resident, non-motile, elongated macrophages taking up the dye. For experiments with human neutrophils, heparinized whole blood was obtained by venipuncture from healthy donors. Blood samples were obtained from anonymous blood donors enrolled in the NIH Blood Bank research program. Human neutrophils were isolated with Lympholyte-poly Cell Separation Media (Cedarline) as previously described48. Residual erythrocytes were removed using ammonium-chloride-potassium lysis buffer (Lonza).

Focal tissue damage

A protocol for focal skin tissue damage by a focused two-photon laser pulse has been described previously43 and used with slight modifications. The Chameleon XR Ti:sapphire laser (Coherent) was tuned to 850 nm and the laser intensity adjusted to 80 mW. At pixel dimensions of 0.14 × 0.14 µm, a circular region of interest of 25–35 µm in diameter (approximately 1–2 × 10−6 mm3 in volume) (unless otherwise specified) was defined in one focal plane, followed by laser scanning at a pixel dwell time of 0.8 µs for 35–50 iterations, depending on the tissue depth of the imaging field of view. The damage was restricted to dermal layers only (Supplementary Fig. 2). Immediately after laser-induced tissue damage, imaging of the neutrophil response was started at typical voxel dimensions of 0.72 × 0.72 × 2 µm. We performed a maximum of three consecutive experiments per mouse ear.

Data analysis

Three-dimensional object tracking using Imaris (Bitplane) retrieved cell spatial coordinates (x, y, z) over time. These data were further processed using routines composed in the open source programming language R (source code in Supplementary Material) to retrieve dynamic parameters for individual cells (distance-time plot, DTP) and cell populations (radial velocity–time plot). The chemotactic index was defined as cos(α), with a as the angle between the distance vector to the damage site and the actual movement vector (Supplementary Fig. 4). The instantaneous radial velocity is the product of the chemotactic index and the cell’s instantaneous velocity (migrated distance over 30 s). Reconstructed cell tracks were filtered using a moving average with a width of 2.5 min to suppress spurious direction changes due to limited resolution of the tracking algorithm and small scale features such as other cells in the path of the migrating cell. Paths that had durations of less than 3 min were dropped. Velocities and the chemotactic index were calculated using central differences from the filtered paths. Plots including regression lines were generated using the ggplot2 package (version 0.8.9) for R (version 2.13.1).

The accumulation index as measure of cell entry into the collagen-free zone was defined as the ratio of fluorescent signal from gene-deficient cells in the collagen-free zone versus total signal at the wound site divided by the ratio of fluorescent signal from control cells in the collagen-free zone versus total signal at the wound site. Fluorescent signals from static 2P-IVM images were quantified in ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health).

Immunofluorescence in ear skin whole mounts

One to two hours after induction of several focal tissue damage sites, mice were euthanized, ears excised, divided into dorsal and ventral halves, ventral halves fixed in 1% paraformaldehyde (Electron Microscopy Sciences) and stained with antibodies diluted in washing buffer consisting of 1× PBS, 1% BSA and 0.025% (v/v) Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich). For identification of neutrophils in DsRed+/+ Cx3cr1gfp/gfp Tyrc-2J/c-2J mice, ventral ear whole mounts were stained with Alexa Fluor 647 anti-mouse Ly-6G Antibody (clone 1A8, BioLegend)49. For detection of CXCL2 (MIP-2) and CRAMP in neutrophil clusters, anti-MIP2 antibody (R&D Systems), anti-CRAMP antibody (Phoenix Pharmaceuticals), rabbit IgG isotype control and goat IgG isotype control (both Southern Biotech) were all conjugated to Alexa Fluor 555 according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Life Technologies). Fixed ventral ear halves of Lyz2gfp/gfp mice were blocked with 10% normal goat serum or normal rabbit serum (both Southern Biotech) in washing buffer before staining with the Alexa Fluor 555-conjugated antibodies. All Alexa Fluor 555-conjugated antibodies gave strong punctate staining in the dermal tissue, but isotype controls never gave staining within neutrophils. Confocal microscopy on skin whole mounts was performed with a LSM 710 confocal microscope equipped with a 20×/0.8 NA Plan-Apochromat objective (Carl Zeiss Microimaging) using 1-µm optical slices. Statistical analysis. Student’s t-tests were performed after data were confirmed to fulfil the criteria of normal distribution and equal variance; otherwise Mann–Whitney U-tests were applied. Analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism 5 software.

Supplementary Material

Three hours after induction of a 15 s ear skin trauma, endogenous blood-circulating inflammatory cells had entered into the extravascular space of the ear dermis of a DsRed+/+Cx3cr1gfp/gfpTyrc-2J/c-2J mouse before laser-induced focal tissue damage was induced (center). This representative video shows the immediate response of fast-migrating neutrophils (small red cells) towards a focal tissue damage site, while monocytes (green) migrate with slower speeds and follow the developing neutrophil cluster with delay. Accumulating, small DsRed-positive cells were identified as Ly6G-positive neutrophils in Supplementary Fig. 3a differing from other static stromal elements (vessels, hair follicles, skin-resident cells) that are also pseudo-colored in red. Graphic analysis of this video is presented in Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. 3a. Similar neutrophil and monocyte kinetics were observed in DsRed+/+Cx3cr1gfp/+Tyrc-2J/c-2J mice. Two-photon intravital microscopy (x, y, z = 246µm, 246µm, 26µm; merge of z-stack), time-lapse over 2 h (10 frames/s). (.mov; 10.6 MB)

Bone marrow-derived neutrophils from C57BL/6 mice were CMFDA-labeled and injected intradermally into the ventral ear skin of a Tyrc-2J/c-2J mouse 3 h before laser-induced focal tissue damage. This representative video shows the biphasic chemotactic response of neutrophils (pseudo-colored in green) sensing the focal tissue damage (autofluorescence, green) (left) within the fibrous collagenous connective tissue of the ear skin dermis (visualized by second harmonic generation, white) (right). Graphic analysis of this video is presented in Fig. 1c. Two-photon intravital microscopy (x, y, z = 322µm, 351µm, 16µm; merge of z-stack), time-lapse over 49 min 30 s (10 frames/s). (.mov; 4.7 MB)

Neutrophils from C57BL/6 mice were CMFDA-labeled and injected together with propidium iodide (PI) intradermally into the ventral ear skin of a Tyrc-2J/c-2J mouse 2–4 h before laser-induced focal tissue damage. This video shows a single early-recruited neutrophil at the damage site that loses its intracellular dye (green) while its nucleus becomes PI-positive (red) as an indicator of cell death/lysis. Exactly at that time, neutrophils from distant sites increase in speed and directionality and migrate towards the dying neutrophil (left; with motion paths over the last 5 min as white dragon tails, right). At the beginning of the video, some skin-resident cells are PI-positive as a consequence of the intradermal injection and/or unspecific dye uptake. Graphic analysis of this video is presented in Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 4. Two-photon intravital microscopy (x, y, z = 116µm, 155µm, 22µm; merge of z-stack), time-lapse over 21 min 30 s (10 frames/s). (.mov; 1.6 MB)

Various GPCR-deficient (Cxcr2−/−, upper row; Fpr2−/−, middle row; Fpr1−/−, lower row) and control neutrophils were differentially dye-labeled and injected intradermally in a 1:1 ratio into the ventral ear skin of Tyrc-2J/c-2J mice 2–4 h before laser-induced focal tissue damage. This video shows representative experiments of GPCR-deficient (pseudo-colored in yellow) and control neutrophils (pseudo-colored in turquois) migrating side-by-side towards a damage site (left panels) with motion paths over the last 5 min as dragon tails in the corresponding pseudo-color (WT, middle; KO, right panels). Graphic analysis of several experiments is presented in Supplementary Fig. 8 and did not reveal any differences between knockout and control neutrophil dynamics. Two-photon intravital microscopy (x, y, z = 105µm, 147µm, 14–22µm; merge of z-stack), time-lapse over 29 min 30 s (10 frames/s). (.mov; 2.7 MB)

Ltb4r1−/− and control neutrophils were differentially dye-labeled and injected intradermally in a 1:1 ratio into the ventral ear skin of a Tyrc-2J/c-2J mouse 3 h before laser-induced, 25 µm-sized focal tissue damage. This representative video shows Ltb4r1−/− (pseudo-colored in yellow) and control neutrophils (pseudo-colored in turquois) migrating side-by-side towards the damage site (left) with motion paths over the last 10 min as dragon tails in the corresponding pseudo-color (middle and right). Graphic analysis of several experiments is presented in Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 9 and revealed impaired recruitment of Ltb4r1−/− neutrophils with both chemotactic index and velocity reduced at later time points. Two-photon intravital microscopy (x, y, z = 167µm, 209µm, 18µm; merge of z-stack), time-lapse over 30 min (10 frames/s). (.mov; 2.7 MB)

Ltb4r1−/− and control neutrophils were differentially dye-labeled and injected intradermally in a 1:1 ratio into the ventral ear skin of a Tyrc-2J/c-2J mouse 3 h before laser-induced, 10 µm-sized focal tissue damage. This representative video shows Ltb4r1−/− (pseudo-colored in yellow) and control neutrophils (pseudo-colored in turquois) migrating side-by-side towards the damage site (left) with motion paths over the last 10 min as dragon tails in the corresponding pseudo-color (middle and right). Graphic analysis of this experiment is presented in Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. 10 and revealed that Ltb4r1−/− neutrophils are poorly recruited from distant tissue sites. After the experiment, non-motile neutrophils responded with directed migration to a second laser damage (that was set closer to these cells) confirming viability and responsiveness of these cells (not shown). Two-photon intravital microscopy (x, y, z = 167µm, 302µm, 20µm; merge of z-stack), time-lapse over 30 min (10 frames/s). (.mov; 2.8 MB)

Ltb4r1−/− and control neutrophils were differentially dye-labeled and injected intradermally in a 1:1 ratio into the ventral ear skin of a leukotriene-deficient Alox5−/−Tyrc-2J/c-2J mouse 3 h before laser-induced focal tissue damage. This representative video shows Ltb4r1−/− (pseudo-colored in yellow) and control neutrophils (pseudo-colored in turquois) migrating side-by-side towards the damage site (left) with motion paths over the last 10 min as dragon tails in the corresponding pseudo-color (middle and right). Graphic analysis of several experiments is presented in Fig. 2d and Supplementary Fig. 11 and revealed that neutrophil-derived LTB4 improves the interstitial recruitment response of the neutrophil population. Two-photon intravital microscopy (x, y, z = 171µm, 165µm, 16µm; merge of z-stack), time-lapse over 34 min 30 s (10 frames/s). (.mov; 3.2 MB)

Talin-deficient (Tln1−/−) and control neutrophils were differentially dye labeled and injected intradermally in a 1:1 ratio into the ventral ear skin of Tyrc-2J/c-2J mice 2–3 h before laser-induced focal tissue damage was performed. This video shows two representative experiments of Tln1−/− and control neutrophils migrating side-by-side towards a damage site. In upper panels, Tln1−/− neutrophils were labeled with CMTPX (pseudo-colored in red) and control neutrophils with CMFDA (pseudo-colored in green). In lower panels, cell dyes were switched. Cell migration in relation to the fibrous collagenous connective tissue of the ear skin dermis was visualized by second harmonic generation (white; middle column) and motion paths over the last 10 min are presented as yellow dragon tails. Graphic analysis of several experiments is presented in Supplementary Fig. 13 and shows that active integrins are dispensable for interstitial neutrophil recruitment. Two-photon intravital microscopy (x, y, z = 149µm, 159µm, 16–20µm; merge of z-stack), time-lapse over 26 min 30 s (10 frames/s). (.mov; 2.5 MB)

This video shows the collagenous fiber network (visualized by second harmonic generation) as neutrophils accumulate at the focal damage site in the dermis of a LysMgfp/+Tyrc-2J/c-2J mouse (Fig. 3a). Fiber bundles are displaced over time in the x-y-axis. Some disappearing fibers are also displaced in the z-axis out of the imaging volume (not shown). Two-photon intravital microscopy (x, y, z = 122µm, 49µm, 30µm; merge of z-stack), time-lapse over 32 min 30 s (10 frames/s). (.mov; 1.5 MB)

15 s ear skin trauma was induced in a DsRed+/+Tyrc-2J/c-2J mouse (for endogenous blood-circulating neutrophils to enter the extravascular space), 1 h later bone marrow-derived neutrophils from a Lifeact-GFP transgenic mouse were injected intradermally into the ventral ear skin followed 2 h later by laser-induced focal tissue damage. This representative video shows a zoom into the collagen-free wound center where both injected Lifeact-GFP neutrophils (pseudo-colored in green) and endogenous DsRed-positive neutrophils (pseudo-colored in red) migrate in close contact with each other. Lifeact-GFP outlines the actin cortex of neutrophils to demarcate the cell borders of injected individual cells. Two-photon intravital microscopy (x, y, z = 78µm, 78µm, 3µm; merge of z-stack), time-lapse over 34 min 28 s (10 frames/s). (.mov; 12.6 MB)

Talin-deficient (Tln1−/−) and control neutrophils were differentially dye-labeled and injected intradermally in a 1:1 ratio into the ventral ear skin of a Tyrc-2J/c-2J mouse 3 h before laser-induced focal tissue damage. This representative video shows Tln1−/− (pseudo-colored in green) and control neutrophils (pseudo-colored in red) accumulating at the damage site (left). Neutrophil movement in relation to collagen displacement is visualized by second harmonic generation (pseudo-colored in white) (middle, right). Lower panels show zoom-in on the margin of collagen displacement. The analysis of the clustering response is presented in Fig. 3b,c. Two-photon intravital microscopy (x, y, z = 368µm, 368µm, 10µm; merge of z-stack), time-lapse over 29 min 30 s (10 frames/s). (.mov; 2.7 MB)

Itgb2−/− and control neutrophils were differentially dye-labeled and injected intradermally in a 1:1 ratio into the ventral ear skin of a Tyrc-2J/c-2J mouse 3 h before laser-induced focal tissue damage. This representative video shows Itgb2−/− (pseudo-colored in green) and control neutrophils (pseudo-colored in red) accumulating at the damage site (left). Neutrophil movement in relation to collagen displacement is visualized by second harmonic generation (pseudo-colored in white) (middle, right). The analysis of the clustering response is presented in Fig. 3c and Supplementary Fig. 15a. Two-photon intravital microscopy (x, y, z = 368µm, 368µm, 12µm; merge of z-stack), time-lapse over 29 min 30 s (10 frames/s). (.mov; 2.7 MB)

Gnai isoform-deficient and control neutrophils were differentially dye-labeled and injected intradermally in a 1:1 ratio into the ventral ear skin of a Tyrc-2J/c-2J mouse 3 h before laser-induced focal tissue damage. This video shows representative experiments of Gnai2−/− (upper panels) or Gnai3−/− (lower panels) (both pseudo-colored in green) and control neutrophils (pseudo-colored in red) accumulating at the damage site. Neutrophil movement in relation to collagen displacement is visualized by second harmonic generation (pseudo-colored in white) (middle, right). The analysis of the clustering response is presented in Fig. 3f and Supplementary Fig. 15b. Two-photon intravital microscopy (x, y, z = 185µm, 185µm, 14µm; merge of z-stack), time-lapse over 56 min 30 s (10 frames/s). (.mov; 5.1 MB)

Ltb4r1−/− and control neutrophils were differentially dye-labeled and injected intradermally in a 1:1 ratio into the ventral ear skin of a Tyrc-2J/c-2J mouse (upper panels) or leukotriene-deficient Alox5−/−Tyrc-2J/c-2J mouse (lower panels) 3 h before laser-induced focal tissue damage. This video shows representative experiments of Ltb4r1−/− (pseudo-colored in green) and control neutrophils (pseudo-colored in red) accumulating at the damage site of the respective host. Neutrophil movement in relation to collagen displacement is visualized by second harmonic generation (pseudo-colored in white) (middle and right). The analysis of the clustering response is presented in Fig. 3d–f and Supplementary Fig. 15c and 16a. Two-photon intravital microscopy (x, y, z = 185µm, 185µm, 14µm; merge of z-stack), time-lapse over 30 min (10 frames/s). (.mov; 2.7 MB)

Mice were infected with P. aeruginosa-GFP in the footpad before 2P-IVM was performed on the draining popliteal lymph nodes when comparable neutrophil numbers were present in the subcapsular sinus at indicated times after infection (WT: 3 h, Ltb4r1−/−: 4.5 h). Neutrophil-GFP signal is pseudo-colored (heat map) to indicate neutrophil clusters (white) in WT-LysMgfp/+ mice (left) and Ltb4r1−/−LysMgfp/+ mice (right). The analysis of the clustering response is presented in Fig. 4a–c. Time-lapse over 39 min 20 s (10 frames/s). (.mov; 2.6 MB)

Acknowledgements

We thank L. Birnbaumer, R. Fässler, E. Tuomanen, P. M. Murphy, S. Akira, S. Monkley, D. Critchley, R. Wedlich-Söldner and M. Sixt for providing mice for this study, J.G. Egen and J. Tang for assistance with imaging, M. Parsek for providing P. aeruginosa–GFP, J.H. Kehrl, P.M. Murphy, R. Varma and members of the Germain laboratory for discussions. This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health. T.L. was supported by a Human Frontiers Science Program Long-Term Fellowship. W.K. is presently a member of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG)-funded excellence cluster ImmunoSensation, Bonn, Germany.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information is available in the online version of the paper.

Author Contributions: T.L. and R.N.G. designed the experiments, interpreted the data and wrote the paper. P.V.A., J.M.W. and C.A.P. contributed to data interpretation and experimental design, as well as the development of the final version of the paper. T.L. performed all skin-imaging experiments. W.K. performed intravital imaging of infected lymph nodes. B.R.A. developed the software for graphical display of imaging data. T.L., B.R.A. and P.V.A. conducted quantitative analysis of the data.

The authors declare no competing financial interests. Readers are welcome to comment on the online version of the paper.

References

- 1.Nathan C. Points of control in inflammation. Nature. 2002;420:846–852. doi: 10.1038/nature01320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ley K, Laudanna C, Cybulsky MI, Nourshargh S. Getting to the site of inflammation: the leukocyte adhesion cascade updated. Nature Rev. Immunol. 2007;7:678–689. doi: 10.1038/nri2156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chtanova T, et al. Dynamics of neutrophil migration in lymph nodes during infection. Immunity. 2008;29:487–496. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ng LG, et al. Visualizing the neutrophil response to sterile tissue injury in mouse dermis reveals a three-phase cascade of events. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2011;131:2058–2068. doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peters NC, et al. In vivo imaging reveals an essential role for neutrophils in leishmaniasis transmitted by sand flies. Science. 2008;321:970–974. doi: 10.1126/science.1159194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bruns S, et al. Production of extracellular traps against Aspergillus fumigatus in vitro and in infected lung tissue is dependent on invading neutrophils and influenced by hydrophobin RodA. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000873. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yipp BG, et al. Infection-induced NETosis is a dynamic process involving neutrophil multitasking in vivo. Nature Med. 2012;81:1386–1393. doi: 10.1038/nm.2847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liese J, Rooijakkers SH, van Strijp JA, Novick RP, Dustin ML. Intravital two-photon microscopy of host–pathogen interactions in a mouse model of Staphylococcus aureus skin abscess formation. Cell Microbiol. 2012 doi: 10.1111/cmi.12085. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/cmi.12085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harvie EA, Green JM, Neely MN, Huttenlocher A. Innate immune response to Streptococcus iniae infection in zebrafish larvae. Infect. Immun. 2013;81:110–121. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00642-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kreisel D, et al. In vivo two-photon imaging reveals monocyte-dependent neutrophil extravasation during pulmonary inflammation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:18073–18078. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008737107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nakasone ES, et al. Imaging tumor-stroma interactions during chemotherapy reveals contributions of the microenvironment to resistance. Cancer Cell. 2012;21:488–503. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lämmermann T. Rapid leukocyte migration by integrin-independent flowing and squeezing. Nature. 2008;453:51–55. doi: 10.1038/nature06887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McDonald B, et al. Intravascular danger signals guide neutrophils to sites of sterile inflammation. Science. 2010;330:362–366. doi: 10.1126/science.1195491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guggenberger C, Wolz C, Morrissey JA, Heesemann J. Two distinct coagulase-dependent barriers protect Staphylococcus aureus from neutrophils in a three dimensional in vitro infection model. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002434. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McDonald B, Kubes P. Cellular and molecular choreography of neutrophil recruitment to sites of sterile inflammation. J. Mol. Med. 2011;89:1079–1088. doi: 10.1007/s00109-011-0784-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sanchez-Madrid F, del Pozo MA. Leukocyte polarization in cell migration and immune interactions. EMBO J. 1999;18:501–511. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.3.501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cho H, et al. The loss of RGS protein-Gαi2 interactions results in markedly impaired mouse neutrophil trafficking to inflammatory sites. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2012;32:4561–4571. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00651-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim ND, Chou RC, Seung E, Tager AM, Luster AD. A unique requirement for the leukotriene B4 receptor BLT1 for neutrophil recruitment in inflammatory arthritis. J. Exp. Med. 2006;203:829–835. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen M, et al. Neutrophil-derived leukotriene B4 is required for inflammatory arthritis. J. Exp. Med. 2006;203:837–842. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oyoshi MK, et al. Leukotriene B4-driven neutrophil recruitment to the skin is essential for allergic skin inflammation. Immunity. 2012;37:747–758. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chou RC, et al. Lipid-cytokine-chemokine cascade drives neutrophil recruitment in a murine model of inflammatory arthritis. Immunity. 2010;33:266–278. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sadik CD, Kim ND, Iwakura Y, Luster AD. Neutrophils orchestrate their own recruitment in murine arthritis through C5aR and FccR signaling. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:E3177–E3185. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1213797109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Afonso PV, et al. LTB4 is a signal-relay molecule during neutrophil chemotaxis. Dev. Cell. 2012;22:1079–1091. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.DiPersio JF, Billing P, Williams R, Gasson JC. Human granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor and other cytokines prime human neutrophils for enhanced arachidonic acid release and leukotriene B4 synthesis. J. Immunol. 1988;140:4315–4322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Malawista SE, de Boisfleury Chevance A, van Damme J, Serhan CN. Tonic inhibition of chemotaxis in human plasma. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:17949–17954. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802572105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Palmblad J, et al. Leukotriene B4 is a potent and stereospecific stimulator of neutrophil chemotaxis and adherence. Blood. 1981;58:658–661. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ford-Hutchinson AW, Bray MA, Doig MV, Shipley ME, Smith MJ. Leukotriene B, a potent chemokinetic and aggregating substance released from polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Nature. 1980;286:264–265. doi: 10.1038/286264a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Calderwood DA, Ginsberg MH. Talin forges the links between integrins and actin. Nature Cell Biol. 2003;5:694–697. doi: 10.1038/ncb0803-694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kastenmüller W, Torabi-Parizi P, Subramanian N, Lämmermann T, Germain RN. A spatially-organized multicellular innate immune response in lymph nodes limits systemic pathogen spread. Cell. 2012;150:1235–1248. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

ASSOCIATED REFERENCES

- 30.Rudolph U, et al. Ulcerative colitis and adenocarcinoma of the colon in Gαi2-deficient mice. Nature Genet. 1995;10:143–150. doi: 10.1038/ng0695-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pero RS, et al. Gαi2-mediated signaling events in the endothelium are involved in controlling leukocyte extravasation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:4371–4376. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700185104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Potocnik AJ, Brakebusch C, Fässler R. Fetal and adult hematopoietic stem cells require beta1 integrin function for colonizing fetal liver, spleen, and bone marrow. Immunity. 2000;12:653–663. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80216-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Petrich BG, et al. Talin is required for integrin-mediated platelet function in hemostasis and thrombosis. J. Exp. Med. 2007;204:3103–3111. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gao JL, et al. Impaired host defense, hematopoiesis, granulomatous inflammation and type 1-type 2 cytokine balance in mice lacking CC chemokine receptor 1. J. Exp. Med. 1997;185:1959–1968. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.11.1959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gao JL, Lee EJ, Murphy PM. Impaired antibacterial host defense in mice lacking the N-formylpeptide receptor. J. Exp. Med. 1999;189:657–662. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.4.657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen K, et al. A critical role for the G protein-coupled receptor mFPR2 in airway inflammation and immune responses. J. Immunol. 2010;184:3331–3335. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Radin JN, et al. b-Arrestin 1 participates in platelet-activating factor receptor-mediated endocytosis of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Infect. Immun. 2005;73:7827–7835. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.12.7827-7835.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Adachi O, et al. Targeted disruption of the MyD88 gene results in loss of IL-1- and IL-18-mediated function. Immunity. 1998;9:143–150. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80596-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Riedl J, et al. Lifeact mice for studying F-actin dynamics. Nature Methods. 2010;7:168–169. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0310-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Faust N, Varas F, Kelly LM, Heck S, Graf T. Insertion of enhanced green fluorescent protein into the lysozyme gene creates mice with green fluorescent granulocytes and macrophages. Blood. 2000;96:719–726. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Glaccum MB, et al. Phenotypic and functional characterization of mice that lack the type I receptor for IL-1. J. Immunol. 1997;159:3364–3371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gaiser MR, et al. Cancer-associated epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EpCAM;CD326) enables epidermal Langerhans cell motility and migration in vivo. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:E889–E897. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1117674109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li JL, et al. Intravital multiphoton imaging of immune responses in the mouse ear skin. Nature Protocols. 2012;7:221–234. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2011.438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Davies DG, et al. The involvement of cell-to-cell signals in the development of a bacterial biofilm. Science. 1998;280:295–298. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5361.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Boxio R, Bossenmeyer-Pourie C, Steinckwich N, Dournon C, Nusse O. Mouse bone marrow contains large numbers of functionally competent neutrophils. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2004;75:604–611. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0703340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Woodfin A, et al. The junctional adhesion molecule JAM-C regulates polarized transendothelial migration of neutrophils in vivo. Nature Immunol. 2011;12:761–769. doi: 10.1038/ni.2062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kühn R, Schwenk F, Aguet M, Rajewsky K. Inducible gene targeting in mice. Science. 1995;269:1427–1429. doi: 10.1126/science.7660125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Oh H, Siano B, Diamond S. Neutrophil isolation protocol. J. Vis. Exp. 2008;17:745. doi: 10.3791/745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pflicke H, Sixt M. Preformed portals facilitate dendritic cell entry into afferent lymphatic vessels. J. Exp. Med. 2009;206:2925–2935. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Three hours after induction of a 15 s ear skin trauma, endogenous blood-circulating inflammatory cells had entered into the extravascular space of the ear dermis of a DsRed+/+Cx3cr1gfp/gfpTyrc-2J/c-2J mouse before laser-induced focal tissue damage was induced (center). This representative video shows the immediate response of fast-migrating neutrophils (small red cells) towards a focal tissue damage site, while monocytes (green) migrate with slower speeds and follow the developing neutrophil cluster with delay. Accumulating, small DsRed-positive cells were identified as Ly6G-positive neutrophils in Supplementary Fig. 3a differing from other static stromal elements (vessels, hair follicles, skin-resident cells) that are also pseudo-colored in red. Graphic analysis of this video is presented in Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. 3a. Similar neutrophil and monocyte kinetics were observed in DsRed+/+Cx3cr1gfp/+Tyrc-2J/c-2J mice. Two-photon intravital microscopy (x, y, z = 246µm, 246µm, 26µm; merge of z-stack), time-lapse over 2 h (10 frames/s). (.mov; 10.6 MB)

Bone marrow-derived neutrophils from C57BL/6 mice were CMFDA-labeled and injected intradermally into the ventral ear skin of a Tyrc-2J/c-2J mouse 3 h before laser-induced focal tissue damage. This representative video shows the biphasic chemotactic response of neutrophils (pseudo-colored in green) sensing the focal tissue damage (autofluorescence, green) (left) within the fibrous collagenous connective tissue of the ear skin dermis (visualized by second harmonic generation, white) (right). Graphic analysis of this video is presented in Fig. 1c. Two-photon intravital microscopy (x, y, z = 322µm, 351µm, 16µm; merge of z-stack), time-lapse over 49 min 30 s (10 frames/s). (.mov; 4.7 MB)

Neutrophils from C57BL/6 mice were CMFDA-labeled and injected together with propidium iodide (PI) intradermally into the ventral ear skin of a Tyrc-2J/c-2J mouse 2–4 h before laser-induced focal tissue damage. This video shows a single early-recruited neutrophil at the damage site that loses its intracellular dye (green) while its nucleus becomes PI-positive (red) as an indicator of cell death/lysis. Exactly at that time, neutrophils from distant sites increase in speed and directionality and migrate towards the dying neutrophil (left; with motion paths over the last 5 min as white dragon tails, right). At the beginning of the video, some skin-resident cells are PI-positive as a consequence of the intradermal injection and/or unspecific dye uptake. Graphic analysis of this video is presented in Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 4. Two-photon intravital microscopy (x, y, z = 116µm, 155µm, 22µm; merge of z-stack), time-lapse over 21 min 30 s (10 frames/s). (.mov; 1.6 MB)

Various GPCR-deficient (Cxcr2−/−, upper row; Fpr2−/−, middle row; Fpr1−/−, lower row) and control neutrophils were differentially dye-labeled and injected intradermally in a 1:1 ratio into the ventral ear skin of Tyrc-2J/c-2J mice 2–4 h before laser-induced focal tissue damage. This video shows representative experiments of GPCR-deficient (pseudo-colored in yellow) and control neutrophils (pseudo-colored in turquois) migrating side-by-side towards a damage site (left panels) with motion paths over the last 5 min as dragon tails in the corresponding pseudo-color (WT, middle; KO, right panels). Graphic analysis of several experiments is presented in Supplementary Fig. 8 and did not reveal any differences between knockout and control neutrophil dynamics. Two-photon intravital microscopy (x, y, z = 105µm, 147µm, 14–22µm; merge of z-stack), time-lapse over 29 min 30 s (10 frames/s). (.mov; 2.7 MB)

Ltb4r1−/− and control neutrophils were differentially dye-labeled and injected intradermally in a 1:1 ratio into the ventral ear skin of a Tyrc-2J/c-2J mouse 3 h before laser-induced, 25 µm-sized focal tissue damage. This representative video shows Ltb4r1−/− (pseudo-colored in yellow) and control neutrophils (pseudo-colored in turquois) migrating side-by-side towards the damage site (left) with motion paths over the last 10 min as dragon tails in the corresponding pseudo-color (middle and right). Graphic analysis of several experiments is presented in Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 9 and revealed impaired recruitment of Ltb4r1−/− neutrophils with both chemotactic index and velocity reduced at later time points. Two-photon intravital microscopy (x, y, z = 167µm, 209µm, 18µm; merge of z-stack), time-lapse over 30 min (10 frames/s). (.mov; 2.7 MB)

Ltb4r1−/− and control neutrophils were differentially dye-labeled and injected intradermally in a 1:1 ratio into the ventral ear skin of a Tyrc-2J/c-2J mouse 3 h before laser-induced, 10 µm-sized focal tissue damage. This representative video shows Ltb4r1−/− (pseudo-colored in yellow) and control neutrophils (pseudo-colored in turquois) migrating side-by-side towards the damage site (left) with motion paths over the last 10 min as dragon tails in the corresponding pseudo-color (middle and right). Graphic analysis of this experiment is presented in Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. 10 and revealed that Ltb4r1−/− neutrophils are poorly recruited from distant tissue sites. After the experiment, non-motile neutrophils responded with directed migration to a second laser damage (that was set closer to these cells) confirming viability and responsiveness of these cells (not shown). Two-photon intravital microscopy (x, y, z = 167µm, 302µm, 20µm; merge of z-stack), time-lapse over 30 min (10 frames/s). (.mov; 2.8 MB)

Ltb4r1−/− and control neutrophils were differentially dye-labeled and injected intradermally in a 1:1 ratio into the ventral ear skin of a leukotriene-deficient Alox5−/−Tyrc-2J/c-2J mouse 3 h before laser-induced focal tissue damage. This representative video shows Ltb4r1−/− (pseudo-colored in yellow) and control neutrophils (pseudo-colored in turquois) migrating side-by-side towards the damage site (left) with motion paths over the last 10 min as dragon tails in the corresponding pseudo-color (middle and right). Graphic analysis of several experiments is presented in Fig. 2d and Supplementary Fig. 11 and revealed that neutrophil-derived LTB4 improves the interstitial recruitment response of the neutrophil population. Two-photon intravital microscopy (x, y, z = 171µm, 165µm, 16µm; merge of z-stack), time-lapse over 34 min 30 s (10 frames/s). (.mov; 3.2 MB)

Talin-deficient (Tln1−/−) and control neutrophils were differentially dye labeled and injected intradermally in a 1:1 ratio into the ventral ear skin of Tyrc-2J/c-2J mice 2–3 h before laser-induced focal tissue damage was performed. This video shows two representative experiments of Tln1−/− and control neutrophils migrating side-by-side towards a damage site. In upper panels, Tln1−/− neutrophils were labeled with CMTPX (pseudo-colored in red) and control neutrophils with CMFDA (pseudo-colored in green). In lower panels, cell dyes were switched. Cell migration in relation to the fibrous collagenous connective tissue of the ear skin dermis was visualized by second harmonic generation (white; middle column) and motion paths over the last 10 min are presented as yellow dragon tails. Graphic analysis of several experiments is presented in Supplementary Fig. 13 and shows that active integrins are dispensable for interstitial neutrophil recruitment. Two-photon intravital microscopy (x, y, z = 149µm, 159µm, 16–20µm; merge of z-stack), time-lapse over 26 min 30 s (10 frames/s). (.mov; 2.5 MB)

This video shows the collagenous fiber network (visualized by second harmonic generation) as neutrophils accumulate at the focal damage site in the dermis of a LysMgfp/+Tyrc-2J/c-2J mouse (Fig. 3a). Fiber bundles are displaced over time in the x-y-axis. Some disappearing fibers are also displaced in the z-axis out of the imaging volume (not shown). Two-photon intravital microscopy (x, y, z = 122µm, 49µm, 30µm; merge of z-stack), time-lapse over 32 min 30 s (10 frames/s). (.mov; 1.5 MB)

15 s ear skin trauma was induced in a DsRed+/+Tyrc-2J/c-2J mouse (for endogenous blood-circulating neutrophils to enter the extravascular space), 1 h later bone marrow-derived neutrophils from a Lifeact-GFP transgenic mouse were injected intradermally into the ventral ear skin followed 2 h later by laser-induced focal tissue damage. This representative video shows a zoom into the collagen-free wound center where both injected Lifeact-GFP neutrophils (pseudo-colored in green) and endogenous DsRed-positive neutrophils (pseudo-colored in red) migrate in close contact with each other. Lifeact-GFP outlines the actin cortex of neutrophils to demarcate the cell borders of injected individual cells. Two-photon intravital microscopy (x, y, z = 78µm, 78µm, 3µm; merge of z-stack), time-lapse over 34 min 28 s (10 frames/s). (.mov; 12.6 MB)

Talin-deficient (Tln1−/−) and control neutrophils were differentially dye-labeled and injected intradermally in a 1:1 ratio into the ventral ear skin of a Tyrc-2J/c-2J mouse 3 h before laser-induced focal tissue damage. This representative video shows Tln1−/− (pseudo-colored in green) and control neutrophils (pseudo-colored in red) accumulating at the damage site (left). Neutrophil movement in relation to collagen displacement is visualized by second harmonic generation (pseudo-colored in white) (middle, right). Lower panels show zoom-in on the margin of collagen displacement. The analysis of the clustering response is presented in Fig. 3b,c. Two-photon intravital microscopy (x, y, z = 368µm, 368µm, 10µm; merge of z-stack), time-lapse over 29 min 30 s (10 frames/s). (.mov; 2.7 MB)

Itgb2−/− and control neutrophils were differentially dye-labeled and injected intradermally in a 1:1 ratio into the ventral ear skin of a Tyrc-2J/c-2J mouse 3 h before laser-induced focal tissue damage. This representative video shows Itgb2−/− (pseudo-colored in green) and control neutrophils (pseudo-colored in red) accumulating at the damage site (left). Neutrophil movement in relation to collagen displacement is visualized by second harmonic generation (pseudo-colored in white) (middle, right). The analysis of the clustering response is presented in Fig. 3c and Supplementary Fig. 15a. Two-photon intravital microscopy (x, y, z = 368µm, 368µm, 12µm; merge of z-stack), time-lapse over 29 min 30 s (10 frames/s). (.mov; 2.7 MB)

Gnai isoform-deficient and control neutrophils were differentially dye-labeled and injected intradermally in a 1:1 ratio into the ventral ear skin of a Tyrc-2J/c-2J mouse 3 h before laser-induced focal tissue damage. This video shows representative experiments of Gnai2−/− (upper panels) or Gnai3−/− (lower panels) (both pseudo-colored in green) and control neutrophils (pseudo-colored in red) accumulating at the damage site. Neutrophil movement in relation to collagen displacement is visualized by second harmonic generation (pseudo-colored in white) (middle, right). The analysis of the clustering response is presented in Fig. 3f and Supplementary Fig. 15b. Two-photon intravital microscopy (x, y, z = 185µm, 185µm, 14µm; merge of z-stack), time-lapse over 56 min 30 s (10 frames/s). (.mov; 5.1 MB)

Ltb4r1−/− and control neutrophils were differentially dye-labeled and injected intradermally in a 1:1 ratio into the ventral ear skin of a Tyrc-2J/c-2J mouse (upper panels) or leukotriene-deficient Alox5−/−Tyrc-2J/c-2J mouse (lower panels) 3 h before laser-induced focal tissue damage. This video shows representative experiments of Ltb4r1−/− (pseudo-colored in green) and control neutrophils (pseudo-colored in red) accumulating at the damage site of the respective host. Neutrophil movement in relation to collagen displacement is visualized by second harmonic generation (pseudo-colored in white) (middle and right). The analysis of the clustering response is presented in Fig. 3d–f and Supplementary Fig. 15c and 16a. Two-photon intravital microscopy (x, y, z = 185µm, 185µm, 14µm; merge of z-stack), time-lapse over 30 min (10 frames/s). (.mov; 2.7 MB)

Mice were infected with P. aeruginosa-GFP in the footpad before 2P-IVM was performed on the draining popliteal lymph nodes when comparable neutrophil numbers were present in the subcapsular sinus at indicated times after infection (WT: 3 h, Ltb4r1−/−: 4.5 h). Neutrophil-GFP signal is pseudo-colored (heat map) to indicate neutrophil clusters (white) in WT-LysMgfp/+ mice (left) and Ltb4r1−/−LysMgfp/+ mice (right). The analysis of the clustering response is presented in Fig. 4a–c. Time-lapse over 39 min 20 s (10 frames/s). (.mov; 2.6 MB)