Abstract

The class A G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) Orexin-1 (OX1) and Orexin-2 (OX2) are located predominantly in the brain and are linked to a range of different physiological functions, including the control of feeding, energy metabolism, modulation of neuro-endocrine function, and regulation of the sleep–wake cycle. The natural agonists for OX1 and OX2 are two neuropeptides, Orexin-A and Orexin-B, which have activity at both receptors. Site-directed mutagenesis (SDM) has been reported on both the receptors and the peptides and has provided important insight into key features responsible for agonist activity. However, the structural interpretation of how these data are linked together is still lacking. In this work, we produced and used SDM data, homology modeling followed by MD simulation, and ensemble-flexible docking to generate binding poses of the Orexin peptides in the OX receptors to rationalize the SDM data. We also developed a protein pairwise similarity comparing method (ProS) and a GPCR-likeness assessment score (GLAS) to explore the structural data generated within a molecular dynamics simulation and to help distinguish between different GPCR substates. The results demonstrate how these newly developed methods of structural assessment for GPCRs can be used to provide a working model of neuropeptide–Orexin receptor interaction.

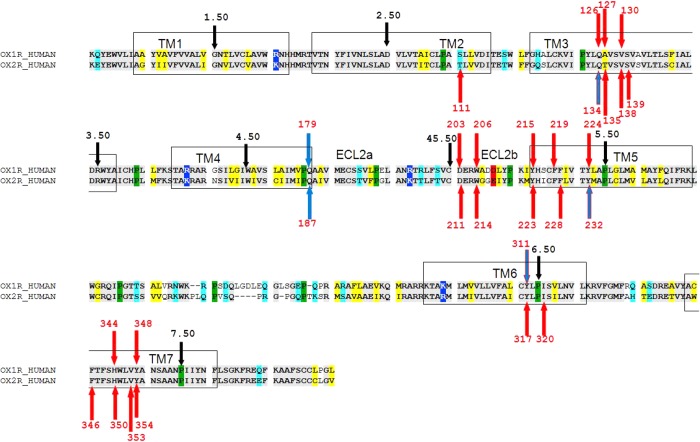

The class A G-protein-coupled receptors Orexin-1 (OX1) and Orexin-2 (OX2) are located predominantly in the hypothalamus and locus coeruleus1,2 but are also found elsewhere in the central nervous system.3,4 The Orexin (OX) receptors are highly conserved across mammalian species. The human (h) OX1 and OX2 receptors have 64% identical overall sequences, being 84% identical in the transmembrane regions. The sequence alignment of hOX1 and hOX2 is shown in Figure 1. The OX receptors are linked to a range of different physiological functions, including the control of feeding, energy metabolism, modulation of neuroendocrine function,5,6 and regulation of the sleep–wake cycle.7,8 They are also associated with dopaminergic neurons of the ventral tegmental area (VTA)9 that are critical elements of the reward system.10 Although the hypothalamic OX system is known to regulate appetitive behaviors11,12 and promote wakefulness and arousal,13 this system may also be important in adaptive and pathological anxiety/stress responses.14−16

Figure 1.

Sequence alignment of hOX1 (OX1R_HUMAN) and hOX2 (OX2R_HUMAN). The background color coding is as follows: gray for identical residues, yellow for chemically homologous residues, cyan for polar residues, blue for positive residues, red for negative residues, and green for prolines. The key residues that were involved in SDM are shown by colored arrows: red arrows for residues mutated by other researchers, blue arrows for mutations introduced by us, and blue arrows with a red outline for mutations introduced by other researchers and by us. The conserved residue in each TM that is assigned to 50 according to the Ballesteros–Weinstein numbering scheme is denoted with a black arrow. The red numbers are the amino acid numbers as they are appear in sequences of OX1 (O43613) and human OX2 (O43614), which were retrieved from the Swiss-Prot database.

Over the past decade, a large number of OX antagonists have been developed as potential drugs for various physiological disorders involving the Orexin system. Currently, the most clinically advanced Orexin antagonist is Suvorexant17 for the treatment of insomnia. However, it is not only OX antagonists that have therapeutic potential;15,18 it has also been shown that agonists of OX receptors have potential18−20 for the treatment of various diseases, including narcolepsy, obesity, hypophagia, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder,18 bipolar disorders, Parkinson’s disease,21 and colon cancer.22 By extension, understanding OX receptor agonist binding is also important for developing inverse agonists or antagonists that block this activity. Moreover, the study of OX agonists is especially important in light of “biased signaling” of GPCR ligands23 and the recent discovery that OX receptors can also signal via the β2-arrestin signaling pathway.24 This observation is particularly important because many of the antagonists originally thought to block one signaling pathway have a second “hidden” activity as agonists of second signaling pathways, as was shown for the antagonists of human H4.25 Thus, in light of the broad medicinal evidence of the importance of OX receptors as potential drug targets,7,26,27 there is a need for the exploration of the key structural features of OX receptors involved in agonist potency, efficacy, and selectivity. Such information is vital for driving the development of the first OX receptor nonpeptidic agonists28,29 or even for improving antagonist performance.7,30

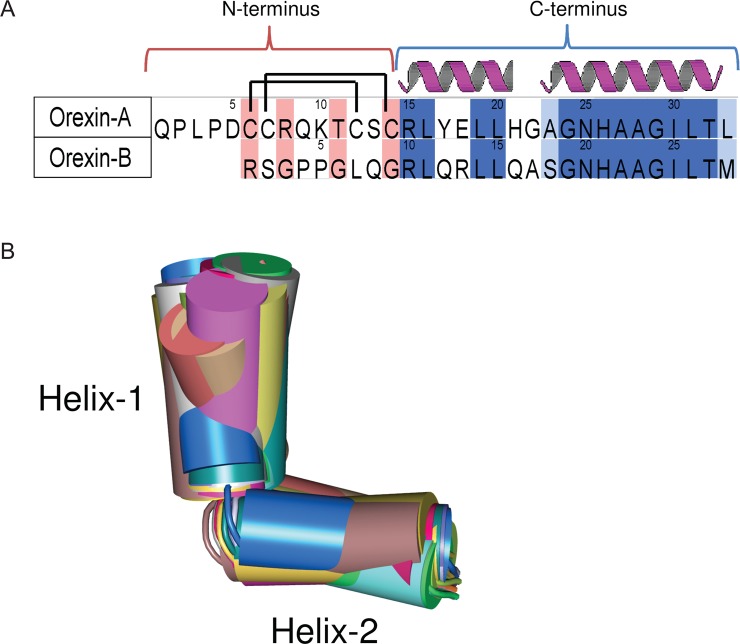

It was discovered that hypothalamic neuropeptides Orexin-A/hypocretin-1 [OxA, 33 amino acids (see Figure 2A)]31 and Orexin-B/hypocretin-2 [OxB, 28 amino acids (see Figure 2A)]32 agonize their effect through OX1 and OX2 receptors that couple to Gq/11 and contribute to the activation of phospholipase C, leading to the elevation of intracellular Ca2+ concentrations.33 The Orexin peptides can be divided into two small “domains”, the N-terminus (residues 1–14 in OxA and 1–9 in OxB) and the C-terminus [residues 15–33 in OxA and 10–28 in OxB (see Figure 2A)]. In spite of the functional homology, the Orexin peptides share similarity (79%) only in the C-terminal domain. The N-terminus of OxA contains two intramolecular disulfide bonds formed between C6 and C12 and between C7 and C14. The C-termini of the Orexins are comprised of two consensus α-helices34 connected by a short loop that generates a kink between them.

Figure 2.

(A) Amino acid sequence alignment of human Orexin-A with human Orexin-B, which was retrieved from the Swiss-Prot database (entry O43612). The background color coding is as follows: dark blue for identical residues, light blue for chemically homologous residues, and pink for chemically nonhomologous residues. Two intramolecular disulfide bonds in Orexin-A formed between C6 and C12 and between C7 and C14 are shown as lines. Consensus helical structures34 are marked with red dashed line. (B) Thirty conformations of the C-terminus truncated from OxA structures determined by NMR and extracted from PDB entry 1WSO.34 The helical domains are represented by cylinders and loops by tubes. The structures are colored randomly accordingly to their number in the PDB entry.

Recently, several site-directed mutagenesis35−37 studies were conducted to reveal the key residues in both Orexin receptors (Table 1) and the peptide (Table 2) responsible for their mutual potency and efficacy. Key residues of OxA and OxB required for their binding to the OX1 and OX2 receptors have been explored using truncated peptides and alanine scan approaches, in which each of the peptide residues was systematically substituted with alanine36,38 or in the case of alanine with glycine. It was observed38 that deletion of the N-terminal domain produces a decrease in the efficacy of OxA to OX1; however, a C-terminus alone retains a significant agonist effect.35,38 The biological activity of the mutated peptides was estimated from the transient mobilization of the intracellular calcium concentration, which was mediated by the receptors bound to wild type and mutated peptides.

Table 1. Comparison of the Effects of Different Mutations in hOX1 and hOX2 on the Binding Potencies of Orexin-A and Orexin-Ba.

| hOX1 |

hOX2 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7TM position | mutation | ratiob of Orexin-A | ratiob of Orexin-B | mutation | ratiob of Orexin-A | ratiob of Orexin-B |

| 2.61 | S103A | NMf | T111A | 243.5c | ||

| 3.32 | Q126A | 2.4c | Q134A | 22.3c/15.1d | 5.1d | |

| 3.33 | A127T | 1.8c | T135A | 0.8c | ||

| 3.36 | V130A | 30.6c | V138A | 4.4c | ||

| 3.37 | S139A | 2.5c | ||||

| 45.51 | D203A | 408.2c | D211A | 416.1c | ||

| 45.54 | W206A | 417.8c | W214A | 62.4c | ||

| 4.60 | Q179A | 17.8d fold improvement | 72.2d fold improvement | Q187A | 1.3d | 1.7d |

| 5.38 | Y215A | 407.8c | Y223A | 183.9c | ||

| 5.42 | F219A | 139.6c | F227A | 240.3c | ||

| 5.42 | F227W | 84.2d | 75.0d | |||

| 5.43 | F228A | 3.0c | ||||

| 5.47 | Y224A | 84.4c | Y232A | 28.4c | ||

| 6.48 | Y311A | 163.9c/ NDe | NDe | Y317A | 17.7c | |

| 6.48 | Y311F | 1.6d | 0.85d | Y317F | 1.3c | |

| 6.51 | I320A | 0.9c | ||||

| 7.35 | F346A | 54.5c | ||||

| 7.39 | H344A | 241.1c | H350A | 49.5c | ||

| 7.42 | V353A | 1.9c | ||||

| 7.43 | Y348A | 8.7c | Y354A | 3.7c | ||

Determination of the effect of point mutations on the potencies of OX endogenous agonists relative (ratio) to the wild type. The mutations that have a large (≥10-fold) effect are shown in bold.

EC50(mut)/EC50(WT).

SDM data generated by Malherbe et al.37

SDM data generated in this work.

No activity detected.

Not measured

Table 2. Effect of Alanine Scanning on the Potencies of Truncated OxA and OxB with Respect to hOX1 and hOX2a.

| OX1 |

OX2 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OxA residue | OxB residue | OxA34,38 | OxB36 | OxA35 | OxB36 |

| R15 | R10 | = | ↓ | = | ↓ |

| L16 | L11 | ↓ | ↓ (L11S ↓↓↓) | = | = |

| Y17 | Q12 | = | = | = | = |

| E18 | R13 | = | = | = | = |

| L19 | L14 | ↓↓ | = | = | = |

| L20 | L15 | ↓↓ | ↓↓ | ↓↓ | ↓↓ |

| H21 | Q16 | = | = | = | = |

| G22 | A17 | = | = | = | = |

| A23 | S18 | = | = | NMb | ↓↓ |

| G24 | G19 | = | ↓ | = | ↓ |

| N25 | N20 | = | ↓↓ | = | ↓↓ |

| H26 | H21 | ↓↓ | = | ↓ | = |

| A27G | A22G | ↓↓ | ↓ | ↓↓ | = |

| A28G | A23G | ↓↓ | ↓↓ | ↓↓ | ↓ |

| G29 | G24 | ↓↓↓ | ↓↓↓ | ↓↓↓ | ↓↓↓ |

| I30 | I25 | ↓↓↓ | ↓↓↓ | ↓↓↓ | ↓↓↓ |

| L31 | L26 | ↓↓↓ | ↓↓↓ | ↓↓↓ | ↓↓↓ |

| T32 | T27 | ↓↓↓ | ↓↓↓ | ↓↓↓ | ↓↓↓ |

| L33 | M28 | ↓↓↓ | ↓↓↓ | ↓↓↓ | ↓↓↓ |

Notations: =, the same potency as the wild type (mutated/wt ratio of <10-fold); ↓↓↓, no binding potency (mutated/wt ratio of >100-fold); ↓↓, statistically significant decrease in binding potency (mutated/wt ratio of ≥20-fold); ↓, statistically moderate decrease in potency (mutated/wt ratio of ≤10–20-fold). Identical residues are shown in bold.

Not measured.

It was observed36,38 (Table 2) that mutations of the residues in the truncated C-terminus of OxA (L20A, A27A, A28G, G29A, I30A, L31A, T32A, and L33A) significantly reduce peptide potency with respect to both OX1 and OX2 receptors. It was also suggested that the G29A mutation caused a significant disruption of the secondary structure, resulting in a marked decrease in activity. Mutation of L16 and L19 to alanine resulted in a decrease in potency with respect to OX1 but had no effect on OX2. Mutation of H26 to alanine caused a decrease in potency, which was more pronounced for OX1 than for OX2. Other residues of OxA had a negligible effect on potencies with respect to both receptors.

For the truncated C-terminus of OxB, mutations at positions analogous to those of OxA (L15A, N20A, G24A, I25A, L26A, T27A, and M28A) (L33 in OxA) significantly reduce peptide potency with respect to both OX1 and OX2 receptors. Mutations L11A and A22G resulted in a decrease in potency with respect to OX1 but had no effect on that with respect to OX2. Mutation of A23 to glycine caused a decrease in potency, which was more pronounced for OX1 than for OX2. Mutation of the conserved R10 to alanine resulted in a decrease in the potency of OxB with respect to both OX1 and OX2 receptors. Interestingly, the same mutation of (conserved) residue R15 in OxA could be tolerated by both receptors. Mutation of the nonconserved S18 to alanine resulted in a decrease in the potency to OX2 but had no effect on OX1. Mutation of G19 to alanine caused significant disruption to the secondary structure, resulting in a decrease in potency with respect to both OX receptors. Other residues of OxB had a negligible effect on potencies with respect to both receptors.

The receptors themselves have also been the subject of SDM studies with 29 point mutations (18 in hOX2 and 11 in hOX1) that were introduced into the 7TMD region to explore their effect on hOX1 or hOX2 mediation of the Orexin-A-evoked [Ca2+]i response (see Figure 1 and Table 1).37

In OX1, mutations V130A3.36, D203A45.51, W206A45.54, Y215A5.38, F219A5.42, Y224A5.47, Y311A6.48, and H344A7.39 caused large decreases in the potency of OxA (30.6-, 408.2-, 417.8-, 407.8-, 139.6-, 84.4-, 163.9-, and 241.1-fold, respectively) compared with that of the WT (Table 1). Mutations W206A45.54 and Y311A6.48 also resulted in decreases in the maximal efficacy (Emax) of 45.0 and 53.4%, respectively, for OxA and OxB. Other mutations had no major effect on efficacy.

In OX2, mutations T111A2.61, D211A45.51, W214A5.54, Y223A5.38, F227A5.42, F346A7.35, and H350A7.39 caused large decreases in the potency of OxA (243.5-, 416.1-, 62.4-, 183.9-, 240.3-, 54.5-, and 49.5-fold, respectively) without affecting their efficacy compared with that of the WT. Mutations Y232A5.47 and Y317A6.48 resulted in a decrease in both EC50 (by 28.4- and 17.7-fold, respectively) and Emax (44.9 and 49.6%, respectively) of OxA. Mutation Q134A3.32 caused a moderate decrease in the potency of OxA (22.3-fold) without affecting its efficacy.

This SDM data suggests that there is no clear correlation between the importance of residues for potency and for efficacy; residues in positions (Ballesteros and Weinstein39 numbering) 2.61, 45.51, 5.54, 5.38, 5.42, 7.35, and 7.39 are important for the potency of OxA in both receptors, while mutations at other positions (45.45 and 6.48 in OX1 and 5.47 and 6.48 in OX2) reduce both potency and efficacy.

In this work, we used SDM data, OxA NMR structures, OxB models, and OX1 and OX2 models to explain the role of key residues in both peptides and receptors responsible for agonist binding. We used homology modeling followed by MD simulation and ensemble-flexible docking to generate docking poses of Orexins in the inactive or semiactive forms of the OX receptors. We flexibly docked the Orexin peptides into post-MD substates of inactive forms of Orexin receptors. A significant body of evidence suggests that GPCRs are not simple two-state switches but rather encompass a wide spectrum of states, substates and intermediates.40 It has been observed that GPCRs exist in at least two highly populated distinct inactive states and in many intermediate substates.40 Furthermore, recently published NMR data suggest that there is a dynamic equilibrium between functional substates40 of GPCRs and that agonists initially bind to the inactive state of the GPCR and then promote it toward the active state. Ligands play a key role in stabilizing or destabilizing intermediates involved in GPCR activation and have a clear influence on GPCR substate populations. In simplistic terms, a positive enthalpy change upon activation often reflects the loss of stabilizing interhelical interactions associated with the inactive state, while increases in entropy can be associated with increased protein dynamics41 or the release of waters of hydration.42 The addition of an agonist increases the relative population of the activation intermediates for a sufficient period of time to engage a G-protein.40 Dynamic computational techniques such as MD simulations followed by flexible docking have the potential to go beyond the use of static homology models.43−51 They offer a way to sample different functional substates of the GPCRs40,52,53 and for the rationalization of its ligand binding and functional effects.39,54−60 However, when using this approach, one is often unsure of the relevance of all the substates sampled. To help prioritize the analysis of the sampled substates, we developed a new protein pairwise similarity method (ProS) to compare and visualize the structural data generated in an MD run and to cluster the GPCR substructures sampled. To that end, we developed a GPCR-likeness assessment score (GLAS) that allows us to score the clusters according to their agreement with the GPCR conserved 24 inter-TM contacts as described by Venkatakrishnan et al.61

Finally, we validated our modeling results by extending the existing SDM data. Our particular interest was focused on position 4.60, located in the proximity of position 3.33 that was previously identified as being critical for antagonist binding and selectivity. Position 4.60 in TM4 is occupied by conserved residue Q1794.60 in OX1 and Q1874.60 in OX2.

Materials and Methods

Residue Numbering

We used both sequence number and the Ballesteros and Weinstein39 numbering system to identify amino acid positions as described by us previously.62 In the latter, transmembrane (TM) residues are given two numbers; the first is the TM helix number (1–7), while the second indicates the position relative to the most conserved residue in that TM, which is arbitrarily assigned to be 50. We number the loops in a similar manner; for example, the conserved cysteine in extracellular loop 2 (ECL2) would be labeled 45.50, to indicate its presence between TM4 and TM5.

Multiple-Sequence Alignment, Homology Modeling, and Molecular Dynamics

The production of a multiple-sequence alignment and template selection for homology modeling were conducted as previously described by us,62 so here we give a brief account. Sequences of human OX1 (O43613) and human OX2 (O43614) were retrieved from Swiss-Prot database and aligned with four published crystal structures of GPCR receptors [bovine rhodopsin (PDB entry 1U19),63 human dopamine D3 receptor (D3, PDB entry 3PBL),64 human A2A adenosine receptor (A2A, PDB entry 3EML),65 and the β2-adrenergic receptor (β2AR, PDB entry 2RH1)],66 using MOE (version 2010.10, Chemical Computing Group). Potential templates were ranked on the basis of the maximal number of correctly aligned prolines in the 7TMD. The D3 structure had the largest number of aligned prolines and was chosen as the template for homology modeling again using MOE, with the resulting model minimized using the MMFF94x force field.67 To minimize the modeling “noise” between OX receptors and to generate equal starting points for further study, we used the hOX1 model as the template to model hOX2. The models were embedded in a 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (POPC) bilayer using the g_membed feature of GROMACS68 and an energy minimization with a steepest descent algorithm until convergence with a force tolerance of 0.239 kcal mol–1 Å–1 was performed. Sodium and chloride ions were then added to the systems to a concentration of 150 mM followed by a restrained MD run whereby all heavy atoms were restrained by a harmonic potential of 2.39 kcal mol–1 Å–2 for 200 ps. Finally, 50 ns production runs were performed on three repeats that differed in their initial velocities only. MD simulations were conducted with GROMACS version 4.5.469 using the OPLS-AA70,71 force field and TIP3P water molecules72 Production simulations were performed in an NPT ensemble maintained at 310 K and 1 bar. The integration time step was set to 2 fs, and a stochastic dynamics integrator73 was used. Long-range electrostatics were calculated using the particle mesh Ewald (PME) method74 with a 14 Å cutoff and 1 Å space grid. The Lennard-Jones potential used a cutoff of 9 Å, with a switch at 8 Å. The LINCS algorithm75 was used to constrain bond lengths in both the lipid molecules and the protein.

Ensemble-Flexible Docking Protocol

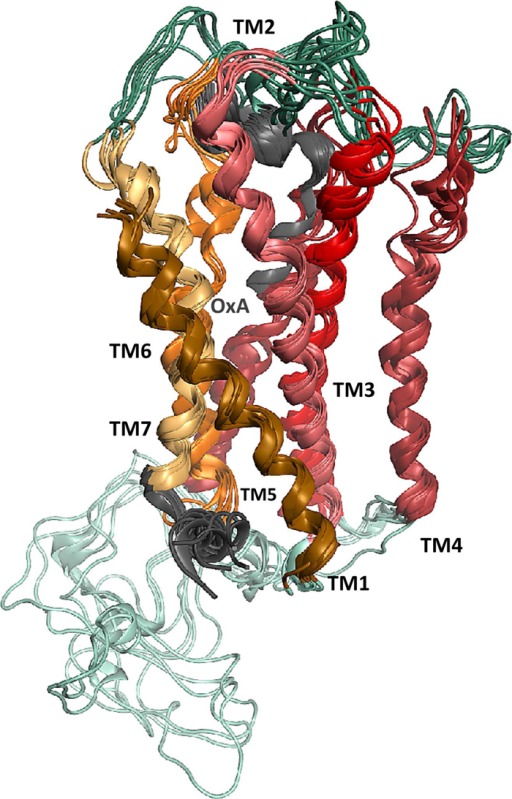

We used the “ensemble-flexible docking protocol”, a built-in function of the GOLD docking package (version 5.0, Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre). The ensemble docking is a procedure that allows simultaneous docking of ligands into multiple substates (structures) of the same GPCR.40,76 When multiple GPCR substates are available, one does not know a priori which substate will give the best docking performance. One strong advantage of ensemble docking is that it very significantly reduces the risk of inadvertently choosing an unsuitable substate model. In our case, the substates of Orexin receptors were retrieved from MD (see Figure 3) simulation runs. Ensemble docking in GOLD version 5.0 uses a genetic algorithm that makes this process more efficient with respect to sequential docking, which requires substantial postprocessing to identify the best ranking poses from the different docking experiments.76

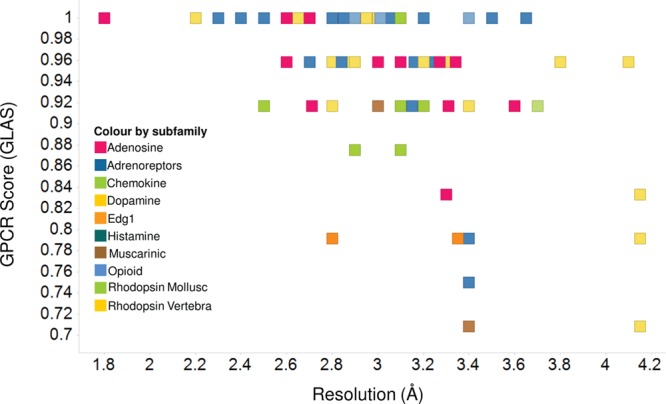

Figure 3.

Plot of the GPCR score vs the X-ray resolution of the 117 GPCR crystal structures extracted from the PDB. The color coding for each of the data points is based on its GPCR subfamily.

We assigned flexibility to key residues in both receptors and peptides using the GOLD rotamer library to improve their steric fit and to ensure that the docking procedure could adjust the site to accommodate large molecules such as Orexin peptides. The list of key residues was taken from SDM data. In the case of OX1, the flexibility was assigned to nine residues: Q1263.32, V1303.36, D20345.51, W20645.54, Y215A5.38, F2195.42, Y2245.47, Y3116.48, and H3447.39. In OX2, the flexibility was assigned to nine residues: Q134A3.32, D21145.51, W2145.54, Y2235.38, F2275.42, Y232A5.47, Y317A6.48, F3467.35, and H3507.39. In the truncated C-terminus of OxA, the flexibility was assigned to nine residues: L16, L19, L20, N25, H26, I30, L31, T32, and L33. In the truncated C-terminus of OxB, the flexibility was assigned to nine residues: L11, L14, L15, N20, H21, I25, L26, T27, and M28.

We docked each conformer of the peptide independently into an ensemble of six receptor substates taken from MD. The docking poses were scored by the GOLD ChemPLP scoring function recommended for ensemble docking,76,77 and we retained the 10 top-ranked docking poses for each receptor–peptide complex. The best pose of the receptor–peptide complex was selected on the basis of the maximal number of interactions between SDM-validated key residues of the receptor and the peptide responsible for peptide potency and efficacy.

Protein Pairwise Similarity (ProS)

We developed a new method, which we call ProS, to analyze and visualize the structural data generated via MD and to cluster the variety of GPCR substructures sampled by MD simulation. We used this tool to compare substates of OX receptors produced in our MD run. In this method, two proteins are considered similar if two conditions occurred simultaneously: (1) if the residues of the relevant pair have the same type evaluated by the substitution matrix blosum65 and (2) if the “positions” and “directions” of the relevant residue pair are similar. In the case of GPCRs, the relevant residue pairs are considered for those residues that have the same Ballesteros and Weinstein index. The position and direction of each residue are defined by the coordinates of its Cα and Cβ atoms, respectively. We assume that if the distance between the Cβ atoms of two relevant residues is small then the side chains of these residues can also adopt similar conformations. The global protein similarity score, SProtein–Similarity, is calculated via eq 1:

| 1 |

where SA(protein 1,protein 2)scaled describes the average similarity in positions and the term SB(protein 1,protein 2) describes the average similarity in residue type and direction of the relevant residue pairs. The term SA(protein 1,protein 2)scaled is calculated via eq 2:

| 2 |

where the score ranges between 0 and 1 (1 indicates 100% similar, and 0 means there is no similarity). N is the number of the relevant pairs, and SA(protein 1,protein 2)i is the individual score calculated per pair using eq 3:

| 3 |

where dCα1i,Cα2 is the distance between Cα atoms of the residues of relevant pair i in proteins 1 and 2. The average SB(protein 1,protein 2)scaled is calculated in the same manner as SA(protein 1,protein 2), and the similarity of residue type and direction of each relevant pair SB(protein 1,protein 2)i is calculated via eq 4:

| 4 |

where dCβ1i,Cβ2 is the distance between Cβ atoms of the residues of relevant pair i in proteins 1 and 2 and α is the substitution score taken from the blossum65 substitution matrix. ProS results are mapped back onto the proteins to allow visualization. Clustering based on ProS was performed using Ward’s clustering method78 as implemented in MOE.

GPCR-Likeness Assessment Score (GLAS)

We also developed a GPCR-likeness assessment score (GLAS) to assess how “GPCR-like” our GPCR models and MD-derived structures (substates) are. GLAS is based on the conserved 24 inter-TM contacts as described by Venkatakrishnan et al.61 In a comparison of the crystal structures of diverse GPCRs using a network representation, it was shown that some of the contacts between TM helices are conserved, in a manner independent of the sequence diversity or functional state of the given GPCR. A systematic analysis of the different GPCR structures, which includes both active and inactive states, revealed a consensus network of 24 inter-TM contacts mediated by 36 topologically equivalent amino acids. In this consensus network, the contacts are present in all (or all but one) of the structures, irrespective of their conformational state, and thus are likely to represent “molecular signatures” of the GPCR fold.61 The significance of the residues in these positions is highlighted by the fact that mutations in 14 of 36 positions have been observed to result in either an increase or a loss of receptor activity.79 The basic assumption in our GLAS scoring function is that high-quality GPCR models must show a large number of these 24 conserved contacts. Here we define that a pair of residues is in contact if the Euclidean distance between any pair of atoms (side chain and/or main chain atoms) is within the van der Waals interaction distance (that is, the sum of the van der Waals radii of the atoms plus 0.6 Å). The list of contacts obtained for the model is compared to the list of 24 conserved contacts. The overall GPCR score for the individual model is the number of its conserved contacts divided by 24 (the maximum), when the highest score is 1 (all 24 contacts are present) and the lowest score is 0 (none of the 24 contacts are present).

Construction of Point-Mutated OX1 and OX2

A combination of overlap and mismatch polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was used to introduce mutations into the corresponding Orexin-1 and Orexin-2 cDNAs as described by us previously.62 Each mutation was made via the generation of two overlapping PCR fragments with PfuUltra II Fusion HS DNA Polymerase (Strategene). The two products were extracted, and a second round of PCR was performed via combination of both fragments with 5′ and 3′ gene specific primers (containing BamHI and NotI restriction sites, respectively). The resulting gel-purified products were then cloned into expression vector pFB-Neo for subsequent generation of stable cell lines. Constructs were confirmed via sequencing. Each verified cDNA was subsequently used to generate single, stably expressing clones in the CHO-K1 cell line.

Calcium Flux Assays

Standard calcium flux assays were used to assess the functionality of each OX receptor mutant. Each CHO-K1 Orexin mutant was seeded into tissue culture-treated, 384-well, black clear-bottom plates (CellBind Corning 7086), at a density of 7500 cells/well in culture medium and maintained in an incubator (5% CO2 at 37 °C) overnight. The cell medium was removed, and the cells were incubated in 20 μL of assay buffer (4 μM Fluo-4AM in HBSS with 0.1% BSA) for 90 min at 37 °C. After incubation, the dye was removed and 45 μL of fresh buffer, without dye, was applied. Antagonists (5 μL) were applied, and after incubation for an additional 20 min at 37 °C, 20 μL of receptor specific agonists was applied and the calcium flux monitored using a Flex Station (Molecular Devices) over a period of 1 min. In all cases, the EC80 specific for the individual mutant as determined in previous experiments was reported.

Results

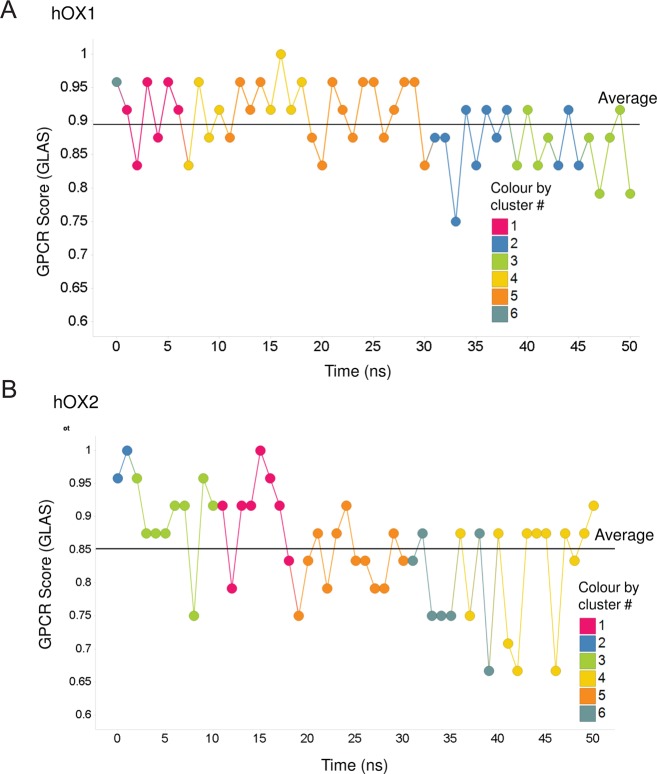

Evaluation of the GPCR Scoring Function (GLAS)

GLAS was calculated for 117 crystal structures of class A GPCRs stored in the PDB (see Table S1 of the Supporting Information). We plotted the GLAS for each crystal structure against its resolution (see Figure 3) and found that the average GLAS decreases with a decreasing resolution in a manner independent of GPCR subfamily; 12 high-resolution (≤2.5 Å) GPCR crystal structures have a GLAS on average of 0.99, 54 structures with a resolution in the range from 2.51 to 3.0 Å a GLAS on average of 0.98, 40 structures with a resolution in the range from 3.0 to 3.5 Å have a GLAS on average of 0.91, and 11 structures with a resolution of >3.5 Å have a GLAS on average of 0.91. The distribution of GLAS versus structure resolution is shown in Figure S1 of the Supporting Information. Although this result is intriguing, the data set is still quite small, and our main motivation for this procedure was to provide a means for assessing how “GPCR-like” our MD-derived structures are.

Modeling of OX1 and OX2 Structures

The modeling procedure of human OX1 and OX2 was as described by us previously.62 Briefly, the homology model of the human OX1 receptor was modeled on the basis of a 2.8 Å high-resolution crystal structure of the dopamine D3 receptor (D3, PDB entry 3PBL). Of the possible templates available in the PDB at the time of preparation of this paper, D3 shared the greatest number of aligned prolines (five in total) with both hOX1 and hOX2 receptors, including the important proline in position 4.59.66 The multiple-sequence alignment is shown in Figure S2 of the Supporting Information. Thus, D3 was preferred as the best template for OX receptor modeling. D3 has also a higher degree of sequence similarity with the hOX1 and hOX2 receptors than other GPCRs (65.5% when comparing just the 7TMD region). The homology model of hOX2 was constructed using the hOX1 model as a template. This was done to minimize the modeling noise between the OX receptors, to ease the comparison between them, and to generate equal starting points for the MD simulation studies. The homology models obtained for hOX1 and hOX2 receptors were employed as starting points for extensive MD simulations in an atomistic model of the membrane. It was observed that after 3 ns of MD, the Cα atom fluctuations over time for all three MD simulation repeats were within the same narrow range of 1.7–2.4 Å,62 which is comparable to the values typically obtained for MD simulations of GPCR crystal structures.80

Clustering of OX1 and OX2 Structures

Initially, we harvested 51 decoys (models) for each OX receptor from the MD run and homology modeling (one structure per nanosecond of the MD run over 50 ns plus one initial homology model). Then we calculated a protein similarity matrix (dimensions of 51 × 51) for these 51 decoys using the ProS method (SProtein–Similarity; see the heat map describing this result in Figure S3A of the Supporting Information for OX1 and Figure S3B of the Supporting Information for OX2) as outlined in Materials and Methods. Next we used this ProS similarity matrix to cluster these 51 decoys using Ward’s clustering method78 (see the hierarchical agglomerative clustering tree in Figure S4 of the Supporting Information for OX1 and Figure S5 of the Supporting Information for OX2) into six clusters. We also calculated the GLAS for each of these 51 decoys and plotted the change in GLAS versus time for the 50 ns MD simulation to evaluate how our simulated structures agree with known crystallographic structures in terms of key, well-conserved features among all GPCRs (see plots in Figure 4A for OX1 and Figure 4B for OX2). It can be seen that the MD structures are as good if not better in this regard than some of the lower-resolution X-ray structures, which we took as reassurance that the MD-generated structures are sensible. We took one representative conformer from each of the six clusters with the highest GLAS for further analysis and docking experiments. It is interesting that the GLAS tends to drift lower with time. However, it is still comparable to the range of GLAS values calculated for crystal structures. Regardless, in this work, we took the top-scored/ranked representative from each cluster observed that was >0.85 (see plots in Figure 4A for OX1 and Figure 4B for OX2), and therefore, we have no reason to suspect our level of confidence should be lower.

Figure 4.

Plots of the GPCR score over time for a 50 ns MD simulation for hOX1 (A) and hOX2 (B) receptors, where the color coding is based on their cluster membership as defined by their ProS.

Modeling the C-Terminus of OxA and OxB

OxA coordinates were taken from the NMR-determined structure (PDB entry 1WSO(34)). We selected the NMR structure of OxA and not the X-ray structure because we were interested in exploring the conformational space of the peptide and not just one snapshot. This was required for our docking procedure. The low-energy “bioactive” conformation of the molecules can frequently be found among the conformations of this molecule in water.81 The structure of the C-terminus of OxA in water34 consists of two α-helices (see Figure 2A) making various angles within a 60–80° range relative to each other and the flexible linker connecting these helices (Figure 2B). The 30 conformations of the C-terminus of OxB were homology modeled on the basis of the 30 conformations of OxA using the alignment as shown in Figure 2A with MOE (version 2010.10, Chemical Computing Group).

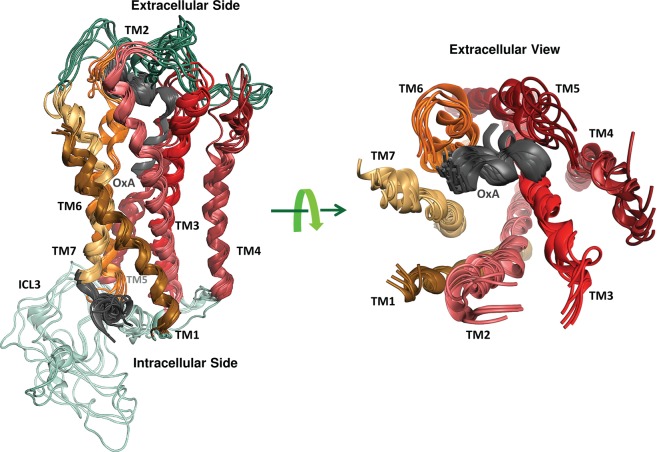

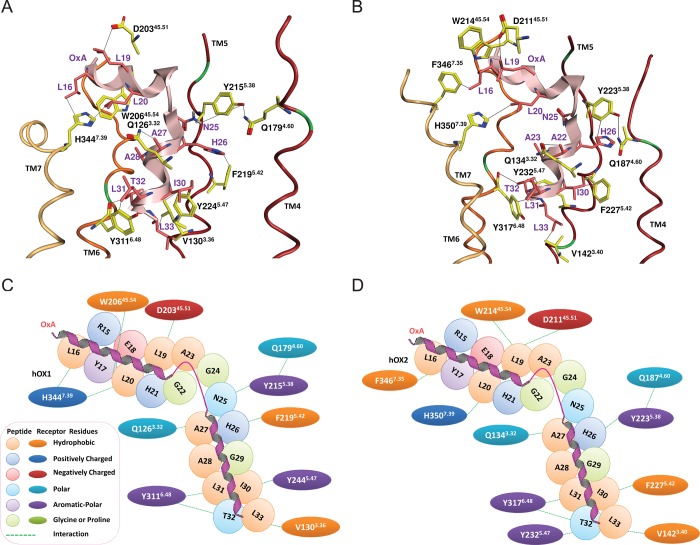

Predicted Mode of Binding of OxA in OX1 and OX2

The 30 conformations of OxA obtained from the NMR ensemble (PDB entry 1WSO) were docked into six conformers of OX1 harvested from MD using the ensemble-flexible docking protocol (see Figure 5). This protocol allows efficient docking of the peptide to the receptor as it is provides sufficient flexibility for both the receptor and the peptide. The 10 top-ranked complexes for OxA, based on the GOLD default scoring function,77 were visually inspected. Of these 10 docking poses, the best pose of OxA in OX1 was selected on the basis of the maximal number of interactions between SDM-validated key residues of OX2 and OxA responsible for OxA potency and efficacy. The proposed docking pose of OxA in the OX1 binding site is shown in Figure 6A, and the two-dimensional (2D) interaction map is shown in Figure 6C. The OX1 binding site for OxA is formed by TMs 3 and 5–7. We explored if the key residues found in the SDM of OX1 generate interactions with the key residues found in the alanine scan of OxA. We predict that residue L16 forms van der Waals type interactions with H3447.39, and D20345.51 is in the proximity of L19 and could potentially form a nonclassical hydrogen bond.82,83 Residues H3447.39 and W20645.54 generate a hydrophobic “sandwich” with L20 of OxA. Q1263.34 forms an interaction with A27 of OxA. N25 is in the proximity of Y2155.38 and could potentially make a hydrogen bond during the activation process. F2195.42 forms a face-to-edge π–π stack with H26. Residues Y2245.47 and V1303.36 generate another hydrophobic sandwich with I30. The Y3116.48 side chain forms van der Waals interactions with L31, and the backbone of Y3116.48 interacts with T32 of OxA (Figure 6A). These last two interactions seem to be essential for both the potency and the efficacy of OxA agonism. The Y311A6.48 mutation results in a large decrease in both the potency and the efficacy of OxA37 and correlates with the same effect of the L31A mutation.38 These predictions are supported by the fact that Y3116.48 is part of the transmission switch (previously called the “toggle switch”) that is proposed to play a role in GPCR activation.84 Finally, L33 generates hydrophobic interactions with V1303.36, which forms part of the conserved VSVSVAVL motif of TM3OX1.

Figure 5.

Six conformations of OX1 with the predicted docking poses of 30 conformations of the C-terminally truncated form of OxA (determined by NMR and extracted from PDB entry 1WSO).34 Transmembrane domains 1–7 are colored dark orange, pink, red, purple, dark red, orange, and light yellow, respectively. Interstrand cross-links are colored cyan, ECLs dark green, and the C-termini of OxA and OX1 gray.

Figure 6.

Best pose of OxA in OX1 (A and C) and OX2 (B and D) models. The loops, TM2 and TM3, were hidden to expose the binding pocket. Transmembrane domains 1–7 are colored dark orange, pink, red, purple, dark red, orange, and light yellow, respectively, and OxA is colored light pink. Only the key residues taken from SDM data are shown; carbon atoms of OxA are colored pink and those of receptors yellow. Nitrogen atoms are colored blue, oxygen atoms red, sulfur atoms yellow, and chlorine atoms light green. Interactions with key residues are indicated by black lines. Panels C and D show a two-dimensional interaction map between OxA and OX receptors.

The same protocol was used to dock the same 30 conformations of OxA into OX2 (see panels B and D of Figure 6) and the same procedure used to evaluate the best pose. The predicted pose suggests that residue L16 forms a hydrophobic interaction with F3467.35. D21145.51 is in the proximity of L19. L19 and L20 form hydrophobic interactions with W21445.54 and H3507.39, respectively. Unlike OX1, N25 of OxA does not form a hydrogen bond with the tyrosine at position 5.38 (Y2155.38 in OX1, but Y2235.38 in OX2). In the case of OX2, Y2235.38 forms an interaction with H26 of OxA. F2275.42 forms a nonpolar interaction with I30. Y3176.48 is in nonpolar contact with L31, and this interaction is essential for both the potency and the efficacy of OxA agonism. Mutating Y3176.48 to alanine results in a decrease in potency of 17.7-fold and efficacy (relative Emax decreases to 49.6%) of OxA,37 which correlates with the L30A mutation in OxA that resulted in the abolishment of both the potency and the efficacy of OxA.38 Similar to OX1, the peptide L33 residue interacts with V1423.40. The side chain of T32 forms a hydrogen bond with the backbone of Y3176.48 and a hydrophobic contact with Y2325.47.

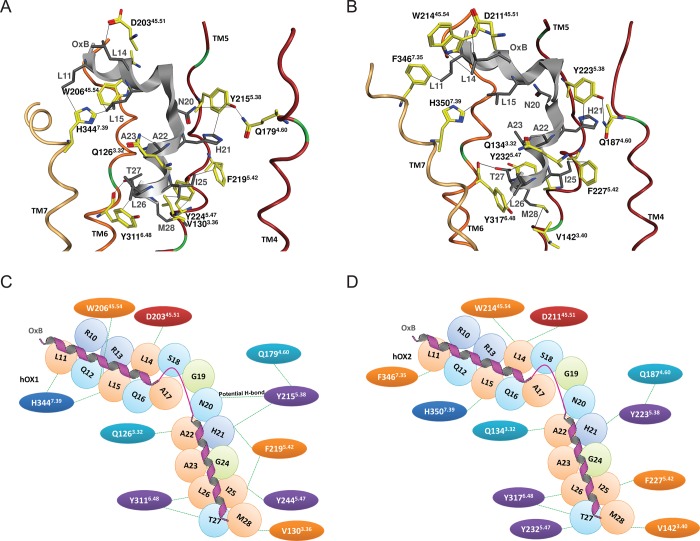

Predicted Mode of Binding of OxB in OX1 and OX2

The same procedure was performed for binding of OxB to OX1 and OX2. The predicted docking pose of OxB in OX1 is shown in Figure 7A along with a 2D interaction map in Figure 7C. The OX1–OxB binding site is formed by TM3 and TM5–7. Unsurprisingly, but reassuringly, we find similar interaction patterns for the OxB peptide compared to the OxA peptide. We predict that L11 of OxB forms a nonpolar interaction with H3447.39. This same histidine along with W20645.54 generates a hydrophobic sandwich with L15. D20345.51 is in the proximity of L14 and could potentially form a nonclassical hydrogen bond.82,83 A potential salt bridge can be formed between R15 and D20345.51. Y2155.38 and N20 are in the proximity of each other and with a slight adjustment could potentially form a reasonable hydrogen bond. Residue F2195.42 forms a nonpolar interaction with H21. Residues Y2245.47 and V1303.36 generate a nonpolar sandwich with I25. Y3116.48 interacts with L26, and the side chain of T27 forms a hydrogen bond with the backbone of Y3116.48. Similar to the situation for OxA, these last two interactions seem to be essential for both the potency and the efficacy of OxB agonism. The Y311A6.48 mutation resulted in a large decrease in both the potency and the efficacy of OxB37 and correlates with the same effect of the L26A mutation, which results in the abolishment of both the potency and the efficacy of OxB.36 Finally, M28 forms a hydrophobic interaction with Y2245.47.

Figure 7.

Best pose of OxB in OX1 (A and C) and OX2 (B and D) models. The loops, TM2 and TM3, were hidden to expose the binding pocket. Transmembrane domains 1–7 are colored dark orange, pink, red, purple, dark red, orange, and light yellow, respectively, and OxB is colored gray. Only the key residues taken from SDM data are shown; carbon atoms of OxB are colored gray and those of receptors yellow. Nitrogen atoms are colored blue, oxygen atoms red, sulfur atoms yellow, and chlorine atoms light green. Interactions with key residues are indicated by black lines. Panels C and D show a two-dimensional interaction map between OxB and OX receptors.

The OX2–OxB binding pose (Figure 7B,D) predicts that residue L11 forms a nonpolar interaction with F3467.35, L14 interacts with W21445.54, and H3507.39 forms a hydrophobic interaction with L15 of OxB. As was the case for OX2–OxB interactions, D21145.51 is in the proximity of L14 and could potentially form a nonclassical hydrogen bond,82,83 and a potential salt bridge could be formed between R15 and D20345.51. Unlike the case in OX1, Y2235.38 (the equivalent in OX1 is Y2155.38) does not interact with N20. F2275.42 forms a nonpolar interaction with I25, and Y3176.48 generates hydrophobic complementarity with L26. Substituting L26 with a d-amino acid resulted in 17000-fold decrease in EC50 compared to that of the wild type.36 As stated before, this latter interaction is likely to be centrally important. M28 forms nonpolar interactions with V1423.40. The side chain of T32 generates a hydrogen bond with the backbone of Y3176.48. On the basis of the SDM data and these modeling observations, it seems that helix 2 of OxA and OxB is playing a major role in Orexin receptor binding and activation.

Discussion

SDM data that have been produced independently for Orexin receptors and for peptides were paired by homology modeling, MD simulation, and ensemble-flexible docking to isolate the key interactions responsible for agonist potency and efficacy. This working model should be useful for the design of nonpeptidic Orexin agonists together with improving the chances of designing selective or “biased” antagonists. In this work, we demonstrate the usefulness of a new, protein pairwise similarity method (ProS) and a GPCR scoring function (GLAS) in analyzing structural data produced by MD simulations. We used homology modeling followed by MD simulation and flexible docking to generate docking poses of Orexins in the inactive or semiactive forms of the OX receptors. We flexibly docked the Orexin peptides into post-MD substates of inactive forms of Orexin receptors.

The docked modes along with the SDM data suggest that helix 2 of OxA and OxB (see Figure 2A) plays a major role in Orexin receptor binding and activation. Mutation of any helix 2 residue (A29–L33 in OxA and A24–M28 in OxB) to alanine (or in case of alanine to glycine) resulted in an almost total loss of the peptides’ potency and efficacy for both Orexin receptors (see Table 2). It seems that for A28 in OxA and A23 in OxB, mutation to glycine has an impact on the α-helical conformation of the peptides. Glycine residues tend to disrupt helices because of their high conformational flexibility, which consequently makes it entropically expensive to adopt the relatively constrained α-helical structure needed to bind to the receptor.85 The α-helical nature of the Orexin peptides in this area is apparently essential for a bioactive conformation and consequent potency and efficacy.

It seems that the aromatic nature of Y6.48 in both receptors is critical for the potency of both agonists. Mutation of Y6.48 to alanine significantly reduces agonist potency37 (see Table 1) for both receptors, but mutation of Y6.48 to phenylalanine had almost no effect on potency. According to our model, Y6.48 in both receptors generates a hydrophobic overlay with the conserved residues, L31 in OxA and L26 in OxB. This interaction seems to be very important for both the potency and the activation by both agonists because (i) the Y6.48A mutation in the receptors, L31A in OxA or L26A in OxB, kills both potency and efficacy and (ii) Y6.48 is part of the transmission switch (previously called the toggle switch) that is associated with GPCR activation.84 Furthermore, the predicted binding modes suggest that the backbone carbonyl of Y6.48 forms an interaction with T32 (in OxA) and T27 (in OxB). Mutation of T32 or T27 in OxA or OxB, respectively, results in a loss of potency.

Mutation of Y5.47 to alanine resulted in a significant decrease in OxA potency. Y5.47 interacts with T32 when OxA is bound to OX1 and with I30 when OxA is bound to OX2. Because residues T32 and I30 are both essential for the potency of OxA, we predict that interactions between Y5.47 and T32 and I30 are critical for receptor activation by OxA. We note that position 5.47 has been found to be involved in agonist binding in other receptors; for example, it plays a role in the binding and activation of β2-adrenergic receptor agonists.86

C-Terminal residues, L33 in OxA and M28 in OxB, appear to play an important role in the activation process. Mutation of these residues to alanine almost abolished potency. We observed that these residues form shape complementarity with the subpocket generated by the VSVSVAVL motif of TM3OX1 or VSVSVSVL motif of TM3OX2. Our results suggest that these long terminal residues, L33 in OxA and M28 in OxB, are responsible for “anchoring” the agonists in the receptor pockets. The OX1 subpocket is more hydrophobic than the OX2 subpocket, because of the presence of alanine at position X in the VSVSVXVL motif in TM3OX1 compared to a serine in TM3OX2. This small difference can impact the subtype selectivity of the peptides. For OxA, L33 generates a nonpolar interaction with V1303.36 that is part of the conserved VSVSVAVL motif of TM3OX1 (see Figure 6A). The V130A3.36 mutation in OX1 reduces the potency by 30.6-fold. However, the V138A3.36 mutation of TM3OX2 had no impact on potency (see Table 1). In our model, L33 of OxA interacts with another valine (V1423.40) that is also part of the conserved VSVSVSVL motif of TM3OX2 (see Figure 6B). The same types of interactions are also formed between M28 of OxB and V1303.36 in OX1 (see Figure 7A) and between M28 of OxB and V1423.40 in OX236 (see Figure 7B). The involvement of TM3 in most GPCR activation processes is a very common phenomenon that has been extensively described in the literature.61,87

We also explored the role of the conserved F5.42. The mutation of this residue to alanine in both receptors reduces the potencies for OxA (see Table 1) and efficacy of OxA in OX2 to 64.3%.37 However, the decrease in potency in the case of OX2 was doubled (240.3-fold) compared to that of OX1 (139.6-fold) (see Table 1). In the case of OX1, F5.42 interacts with H26 of OxA that, based on the SDM experiments, has an only moderate impact on potency (see Figure 6A). This is in contrast to OX2 in which F5.42 interacts with key residue I30 (see Figure 6B). Mutation of I30 of OxA to alanine completely abolished the potency of OxA for both receptors [in the case of OX1, I30 interacts with Y2245.47 (see Figure 6A)]. It seems that in the case of OxB, F5.42 plays a key role in potency for both receptors, by interacting with key residue I25 (see Figure 7A,B). This observation is supported by the SDM data: mutation of F5.42 to tryptophan abolishes the potency of OxB with respect to OX2 (see Table 1), and mutation of I25 to alanine abolishes the potency of OxB for both receptors (see Table 2).

The role of the conserved Y5.38 was also clarified when mutation of this residue to alanine resulted in the abolishment of OxA potency (see Table 1) and a moderate loss of efficacy37 for both receptors. According to the model, Y5.38 is located near the linker (kink) connecting helix 1 and helix 2 of the peptides (see Figure 6A for OX1 and Figure 6B for OX2). We hypothesize that Y5.38 can play a role in stabilizing the relative angle between helix 1 and helix 2 and, by doing so, helps to stabilize the bioactive conformation of OxA in the same mode as OxB (see Figure 7). In the case of OX1, this effect can be supported by the observation that Y2155.38 can potentially form a hydrogen bond with N25 of OxA that is located at the beginning of this flexible linker. However, the generation of this hydrogen bond is hindered by the interhelical hydrogen bond between Y2155.38 and Q1794.60 that limits Y2155.38 flexibility. To validate this hypothesis, we mutated Q1794.60 to alanine, predicting that by breaking this interhelical hydrogen bond we will “release” the Y2155.38 to generate a hydrogen bond with N25, and indeed, it resulted in a 17.8-fold improvement in the potency of OxA with respect to OX1 (see Table 1). In the case of OX2, however, the model predicts that N25 would not form a hydrogen bond with Y2155.38. As predicted when we mutated Q1874.60 (that forms a hydrogen bond with Y2155.38) to alanine, we observed no effect on the binding of OxA to OX2 (see Table 1). Although these results concerning potency agree well with the prediction, we should caution the reader that the experiments are based on our Ca2+ concentration assay and thus do not preclude other possibilities such as destabilization of native states or inhibition of the transition from inactive to active in other ways.

Analogous to the potential interaction between N25 of OxA and Y2155.38, N20 of OxB can potentially form a similar interaction, which again would be hindered by the presence of the interhelical hydrogen bond between Y2155.38 and Q1794.60. We predicted that, in a fashion similar to that of OxA, OxB would be able to form a hydrogen bond via N20 to Y2155.38 if Q1794.60 were mutated to alanine. Consistent with this prediction, the potency of OxB at OX1 was observed to increase 72.2-fold (Table 1). In OX2, we predicted that N20 of OxB does not form a hydrogen bond to Y2155.38; thus, mutating Q1874.60 in this case would not be expected to affect OxB binding, which, again, we observed (Table 1).

An additional residue that plays a key role in OX receptor agonist binding and activation by Orexin peptides is H7.39. Mutation of this residue to alanine resulted in a severe decrease in the potency of OxA (see Table 1) and in 64.5 and 63.0% decreases in its Emax values for OX1 and OX2, respectively.37 We observed that in OX1, H7.39 interacts with residues L16 and L20 of helix 1 of OxA (see Figure 6A). Mutation of L16 or L20 of OxA to alanine resulted in a loss of potency of OxA with respect to OX1. On the other hand, in OX2, H7.39 interacts with L20 and not with L16 (see Figure 6B), and this observation is supported by the SDM data; mutation of L16 to alanine had no effect on the binding of OxA to OX2 compared to the dramatic effect of mutating L20. In the case of OxB, we do not have SDM data for H7.39; however, we predict that H7.39 interacts with residues L11 and L15 of helix 1 of OxB (see Figure 7A). Mutation of L11 or L15 of OxB to alanine resulted in a loss of potency of OxB with respect to OX1. On the other hand, in OX2, H7.39 interacts with L15 only, and not with L11 (see Figure 7B). This observation is supported by the SDM data; mutation of L11 to alanine had no effect on the binding of OxB to OX2 compared to a dramatic effect observed for mutating L15, where a similar selective effect was previously observed by Asahi et al.36

Mutation of D45.51 and W45.54 can also be beneficial for agonist potency. The mutation of these residues to alanine resulted in a loss of potency of OxA for both receptors. We predict that D45.51 generates a steric effect with L19 of OxA for both receptors and W45.54 interacts with L20 of OxA when binding to OX1 (see Figure 6A) and with L19 in OxA when binding to OX2 (see Figure 6B).

It seems to be primarily residues of TM3, -5, and -6 that are involved in both the potency and the efficacy of the agonists. For the discovery of novel nonpeptidic Orexin agonists, we recommend, on the basis of these results, that the main targets for ligand design should be interactions with Y6.48, the hydrophobic motif of VSVSVXVL in TM3, Y5.38, F5.42, Y5.47, and H7.39. Interaction with D45.51 and W45.54 can be beneficial for binding of both agonists and antagonists, as shown in our previous publication.62

In terms of how the result might be interpreted with respect to activation, it seems that the binding of large molecules, like OxA and OxB peptides, to the interior space of the receptor destabilizes its most populated inactive state and, by doing so, promotes the receptor toward the active state. OxA and OxB peptides disturb noncovalent interactions between different TMs, especially the link between TM3 and TM6 formed in the binding site by S3.35 and Y6.48 and the hydrophobic triad of V3.40, L3.43, and F6.44. We observed that hydrogen bonds between S3.35 and Y6.48 (defined when the distance between oxygen atoms of the OH group of S3.35 and Y6.48 is ≤3.5 Å) appear at a frequency of >90% for MD runs of inactive OX1 and >85% for inactive OX2. We observed that the hydrophobic triad of V3.40, L3.43, and F6.44 (defined as present when the distance between the side chain carbon atoms of V3.40, L3.43, and F6.44 is ≤4.5 Å) appears at a frequency of >90% for MD runs of OX1 and OX2. The loss of these interactions potentially has a negative effect on the stability of the inactive state of OX receptors and may induce activation due to the fact that F6.44 and Y6.48 are also part of the transmission switch. The transmission switch includes a relocation of conserved residues, such as F6.44 and Y6.48, toward P5.50. This newly discovered84 and larger switch links the agonist binding site with the movement of TM5 and TM6 through rearrangement of the TM3–TM5–TM6 interface.

Conclusion

The MD simulation protocol used in our work, followed by ensemble-flexible docking, has gone beyond the use of static models and allowed for a more detailed exploration of the OX structures. In this work, we have demonstrated how these methods in combination with SDM data and newly developed post-MD analysis tools can deal with the flexibility of GPCRs to rationalize not only binding affinity but also the potency, efficacy and selectivity of GPCR agonists. The MD simulations allow the prediction of GPCR substates that is not possible with static homology modeling alone.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Markus Kosner and Dr. Simon Grimshaw from Chemical Computing Group for their help in developing the ProS method and the Ballesteros and Weinstein SVL script and Dr. Daniel Warner for his useful discussion about the development of GLAS.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- OX

Orexin receptor

- OX1

OX1R_HUMAN, Orexin-1 receptor

- OX2

OX2R_HUMAN, Orexin-2 receptor

- OxA

human Orexin-A peptide

- OxB

human Orexin-B peptide

- MD

molecular dynamics

- SDM

site-directed mutagenesis

- GPCRs

G-protein-coupled receptors

- 3D

three-dimensional

- 7TMD

seven-transmembrane domain

- TM

transmembrane helix

- ECL

extracellular loop

- β2AR

β2-adrenergic receptor

- PDB

Protein Data Bank

- ProS

protein pairwise similarity score

- GLAS

GPCR-likeness assessment score

- WT

wild type

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance.

Supporting Information Available

Details of the structures used for the development of the ProS scoring function, the multiple-sequence alignment, and MD snapshot analysis. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

We are grateful to the Royal Society for an Industry Award granted to A.H. and to the BBSRC (G.B.M.).

Supplementary Material

References

- Azizi H.; Mirnajafi-Zadeh J.; Rohampour K.; Semnanian S. (2010) Antagonism of orexin type 1 receptors in the locus coeruleus attenuates signs of naloxone-precipitated morphine withdrawal in rats. Neurosci. Lett. 482, 255–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cid-Pellitero E. D.; Garzón M. (2011) Hypocretin1/OrexinA-containing axons innervate locus coeruleus neurons that project to the Rat medial prefrontal cortex. Implication in the sleep-wakefulness cycle and cortical activation. Synapse 65, 843–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laburthe M.; Voisin T.; El Firar A. (2010) Orexins/hypocretins and orexin receptors in apoptosis: A mini-review. Acta Physiol. 198, 393–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazza M.; Della M. G.; Paciello N.; Mennuni G.; Bria P.; Mazza S. (2005) Orexin, sleep and appetite regulation: A review. Clin. Ter. 156, 393–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acuna-Goycolea C.; van den Pol A. N. (2009) Neuroendocrine proopiomelanocortin neurons are excited by Hypocretin/Orexin. J. Neurosci. 29, 1503–1513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toshinai K.; Yamaguchi H.; Kageyama H.; Matsuo T.; Koshinaka K.; Sasaki K.; Shioda S.; Minamino N.; Nakazato M. (2010) Neuroendocrine regulatory peptide-2 regulates feeding behavior via the orexin system in the hypothalamus. Am. J. Physiol. 299, E394–E401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mieda M.; Sakurai T. (2013) Orexin (Hypocretin) receptor agonists and antagonists for treatment of sleep disorders. CNS Drugs 27, 83–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mieda M.; Tsujino N.; Sakurai T. (2013) Differential roles of orexin receptors in the regulation of sleep/wakefulness. Front. Endocrinol. 4, 57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgland S. L.; Taha S. A.; Sarti F.; Fields H. L.; Bonci A. (2006) Orexin A in the VTA is critical for the induction of synaptic plasticity and behavioral sensitization to cocaine. Neuron 49, 589–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi D. L.; Davis J. F.; Fitzgerald M. E.; Benoit S. C. (2010) The role of orexin-A in food motivation, reward-based feeding behavior and food-induced neuronal activation in rats. Neuroscience 167, 11–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benoit S. C.; Clegg D. J.; Woods S. C.; Seeley R. J. (2005) The role of previous exposure in the appetitive and consummatory effects of orexigenic neuropeptides. Peptides 26, 751–757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers R. J.; Halford J. C. G.; Nunes de Souza R. L.; Canto de Souza A. L.; Piper D. C.; Arch J. R. S.; Upton N.; Porter R. A.; Johns A.; Blundell J. E. (2001) SB-334867, a selective orexin-1 receptor antagonist, enhances behavioural satiety and blocks the hyperphagic effect of orexin-A in rats. Eur. J. Neurosci. 13, 1444–1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai T. (2007) [Regulatory mechanism of sleep/wakefulness states by orexin]. Tanpakushitsu Kakusan Koso 52, 1840–1848. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.; Li S.; Wei C.; Wang H.; Sui N.; Kirouac G. (2010) Orexins in the paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus mediate anxiety-like responses in rats. Psychopharmacology 212, 251–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheurink A. J. W.; Boersma G. J.; Nergårdh R.; Södersten P. (2010) Neurobiology of hyperactivity and reward: Agreeable restlessness in Anorexia Nervosa. Physiol. Behav. 100, 490–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki M.; Beuckmann C. T.; Shikata K.; Ogura H.; Sawai T. (2005) Orexin-A (hypocretin-1) is possibly involved in generation of anxiety-like behavior. Brain Res. 1044, 116–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox C. D.; Breslin M. J.; Whitman D. B.; Schreier J. D.; McGaughey G. B.; Bogusky M. J.; Roecker A. J.; Mercer S. P.; Bednar R. A.; Lemaire W.; Bruno J. G.; Reiss D. R.; Harrell C. M.; Murphy K. L.; Garson S. L.; Doran S. M.; Prueksaritanont T.; Anderson W. B.; Tang C.; Roller S.; Cabalu T. D.; Cui D.; Hartman G. D.; Young S. D.; Koblan K. S.; Winrow C. J.; Renger J. J.; Coleman P. J. (2010) Discovery of the dual Orexin receptor antagonist [(7R)-4-(5-chloro-1,3-benzoxazol-2-yl)-7-methyl-1,4-diazepan-1-yl][5-methyl-2-(2H-1,2,3-triazol-2-yl)phenyl]methanone (MK-4305) for the treatment of insomnia. J. Med. Chem. 53, 5320–5332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nollet M.; Leman S. (2013) Role of Orexin in the pathophysiology of depression: Potential for pharmacological intervention. CNS Drugs 27, 411–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nollet M.; Gaillard P.; Minier F.; Tanti A.; Belzung C.; Leman S. (2011) Activation of orexin neurons in dorsomedial/perifornical hypothalamus and antidepressant reversal in a rodent model of depression. Neuropharmacology 61, 336–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nollet M.; Gaillard P.; Tanti A.; Girault V.; Belzung C.; Leman S. (2012) Neurogenesis-independent antidepressant-like effects on behavior and stress axis response of a dual Orexin receptor antagonist in a rodent model of depression. Neuropsychopharmacology 37, 2210–2221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsuki H., and Michinaga S. (2012) Chapter fifteen: Anti-parkinson drugs and Orexin neurons. In Vitamins & Hormones (Gerald L., Ed.) pp 279–290, Academic Press, New York. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mieda M.; Sakurai T. (2012) Overview of orexin/hypocretin system. Prog. Brain Res. 198, 5–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajagopal S.; Rajagopal K.; Lefkowitz R. J. (2010) Teaching old receptors new tricks: Biasing seven-transmembrane receptors. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 9, 373–386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalrymple M. B.; Jaeger W. C.; Eidne K. A.; Pfleger K. D. G. (2011) Temporal profiling of Orexin receptor-arrestin-ubiquitin complexes reveals differences between receptor subtypes. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 16726–16733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nijmeijer S.; Vischer H. F.; Rosethorne E. M.; Charlton S. J.; Leurs R. (2012) Analysis of multiple histamine H4 receptor compound classes uncovers Gαi protein- and β-Arrestin2-biased ligands. Mol. Pharmacol. 82, 1174–1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scammell T. E.; Winrow C. J. (2011) Orexin receptors: Pharmacology and therapeutic opportunities. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 51, 243–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanagisawa M. (2011) Hypothalamic orexin system: From orphan GPCR to therapeutic target. Exp. Anim. 60, 199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto T.; Kunitomo J.; Tomata Y.; Nishiyama K.; Nakashima M.; Hirozane M.; Yoshikubo S.-i.; Hirai K.; Marui S. (2011) Discovery of potent, selective, orally active benzoxazepine-based Orexin-2 receptor antagonists. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 21, 6414–6416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrey D. A.; Gilmour B. P.; Runyon S. P.; Thomas B. F.; Zhang Y. (2011) Diaryl urea analogues of SB-334867 as orexin-1 receptor antagonists. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 21, 2980–2985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebold T. P.; Bonaventure P.; Shireman B. T. (2013) Selective orexin receptor antagonists. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 23, 4761–4769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piper D. C.; Upton N.; Smith M. I.; Hunter A. J. (2000) The novel brain neuropeptide, orexin-A, modulates the sleep–wake cycle of rats. Eur. J. Neurosci. 12, 726–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J.-H.; Bang E.; Chae K.-J.; Kim J.-Y.; Lee D. W.; Lee W. (1999) Solution structure of a new hypothalamic neuropeptide, human hypocretin-2/orexin-B. Eur. J. Biochem. 266, 831–839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai T.; Amemiya A.; Ishii M.; Matsuzaki I.; Chemelli R. M.; Tanaka H.; Williams S. C.; Richardson J. A.; Kozlowski G. P.; Wilson S.; Arch J. R. S.; Buckingham R. E.; Haynes A. C.; Carr S. A.; Annan R. S.; McNulty D. E.; Liu W.-S.; Terrett J. A.; Elshourbagy N. A.; Bergsma D. J.; Yanagisawa M. (1998) Orexins and Orexin Receptors: A family of hypothalamic neuropeptides and G Protein-Coupled Receptors that regulate feeding behavior. Cell 92, 573–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takai T.; Takaya T.; Nakano M.; Akutsu H.; Nakagawa A.; Aimoto S.; Nagai K.; Ikegami T. (2006) Orexin-A is composed of a highly conserved C-terminal and a specific, hydrophilic N-terminal region, revealing the structural basis of specific recognition by the orexin-1 receptor. J. Pept. Sci. 12, 443–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ammoun S.; Lindholm D.; Wootz H.; Åkerman K. E. O.; Kukkonen J. P. (2006) G-protein-coupled OX1 Orexin/hcrtr-1 Hypocretin receptors induce caspase-dependent and -independent cell death through p38 mitogen-/stress-activated protein kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 834–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asahi S.; Egashira S.-I.; Matsuda M.; Iwaasa H.; Kanatani A.; Ohkubo M.; Ihara M.; Morishima H. (2003) Development of an orexin-2 receptor selective agonist, [Ala11, d-Leu15]orexin-B. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 13, 111–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malherbe P.; Roche O.; Marcuz A.; Kratzeisen C.; Wettstein J. G.; Bissantz C. (2010) Mapping the Binding Pocket of Dual Antagonist Almorexant to Human Orexin 1 and Orexin 2 Receptors: Comparison with the Selective OX1 Antagonist SB-674042 and the Selective OX2 Antagonist N-Ethyl-2-[(6-methoxy-pyridin-3-yl)-(toluene-2-sulfonyl)-amino]-N-pyridin-3-ylmethyl-acetamide (EMPA). Mol. Pharmacol. 78, 81–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darker J. G.; Porter R. A.; Eggleston D. S.; Smart D.; Brough S. J.; Sabido-David C.; Jerman J. C. (2001) Structure–activity analysis of truncated orexin-A analogues at the orexin-1 receptor. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 11, 737–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballesteros J. A.; Weinstein H. (1995) Integrated methods for construction three dimensional models and computational probing of structure-function relations in G protein-coupled receptors. Methods Neurosci. 25, 366–428. [Google Scholar]

- Kim T. H.; Chung K. Y.; Manglik A.; Hansen A. L.; Dror R. O.; Mildorf T. J.; Shaw D. E.; Kobilka B. K.; Prosser R. S. (2013) The role of ligands on the equilibria between functional states of a G protein-coupled receptor. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 9465–9474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granier S.; Kim S.; Shafer A. M.; Ratnala V. R. P.; Fung J. J.; Zare R. N.; Kobilka B. (2007) Structure and conformational changes in the C-terminal domain of the β32-adrenoceptor: Insights from fluoresence resonance energy transfer studies. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 13895–13905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoichet B. K.; Kobilka B. K. (2012) Structure-based drug screening for G-protein-coupled receptors. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 33, 268–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bockenhauer S.; Fürstenberg A.; Yao X. J.; Kobilka B. K.; Moerner W. E. (2011) Conformational dynamics of single G protein-coupled receptors in solution. J. Phys. Chem. B 115, 13328–13338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruno A.; Guadix A. E.; Costantino G. (2009) Molecular dynamics simulation of the heterodimeric mglur2/5ht2a complex. An atomistic resolution study of a potential new target in psychiatric conditions. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 49, 1602–1616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filizola M.; Wang S.; Weinstein H. (2006) Dynamic models of G-protein coupled receptor dimers: Indications of asymmetry in the rhodopsin dimer from molecular dynamics simulations in a POPC bilayer. J. Comput.-Aided Mol. Des. 20, 405–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossfield A. (2011) Recent progress in the study of G protein-coupled receptors with molecular dynamics computer simulations. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1808, 1868–1878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallmen C.; Wiese M. (2006) Molecular dynamics simulation of the human adenosine A3 receptor: Agonist induced conformational changes of Trp243. J. Comput.-Aided Mol. Des. 20, 673–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffert J. D.; Pisitkun T.; Saeed F.; Song J. H.; Chou C.-L.; Knepper M. A. (2012) Dynamics of the G protein-coupled vasopressin V2 receptor signaling network revealed by quantitative phosphoproteomics. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 11, M111.014613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura S. R.; Tebben A. J.; Langley D. R. (2008) Expanding GPCR homology model binding sites via a balloon potential: A molecular dynamics refinement approach. Proteins: Struct., Funct., Bioinf. 71, 1919–1929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson L. M.; Wall I. D.; Blaney F. E.; Reynolds C. A. (2011) Modeling GPCR active state conformations: The β2-adrenergic receptor. Proteins: Struct., Funct., Bioinf. 79, 1441–1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jojart B.; Kiss R.; Viskolcz B.; Keseru G. M. (2008) Activation mechanism of the human histamine H4 receptor; An explicit membrane molecular dynamics simulation study. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 48, 1199–1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao Y.; Nichols S. E.; Gasper P. M.; Metzger V. T.; McCammon J. A. (2013) Activation and dynamic network of the M2 muscarinic receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 10982–10987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perilla J. R.; Beckstein O.; Denning E. J.; Woolf T. B. (2010) Computing ensembles of transitions from stable states: Dynamics importance sampling. J. Comput. Chem. 32, 196–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettinelli I.; Graziani D.; Marconi C.; Pedretti A.; Vistoli G. (2011) The approach of conformational chimeras to model the role of proline-containing helices on GPCR mobility: The fertile case of cys-LTR1. ChemMedChem 6, 1217–1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Q.-B.; Wang Z.-Z. (2006) Classification of G-protein coupled receptors at four levels. Protein Eng., Des. Sel. 19, 511–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gloriam D. E.; Foord S. M.; Blaney F. E.; Garland S. L. (2009) Definition of the G protein-coupled receptor transmembrane bundle binding pocket and calculation of receptor similarities for drug design. J. Med. Chem. 52, 4429–4442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall S. E.; Roberts K.; Vaidehi N. (2009) Position of helical kinks in membrane protein crystal structures and the accuracy of computational prediction. J. Mol. Graphics Modell. 27, 944–950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langelaan D. N.; Wieczorek M.; Blouin C.; Rainey J. K. (2010) improved helix and kink characterization in membrane proteins allows evaluation of kink sequence predictors. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 50, 2213–2220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wistrand M.; Käll L.; Sonnhammer E. L. L. (2006) A general model of G protein-coupled receptor sequences and its application to detect remote homologs. Protein Sci. 15, 509–521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yohannan S.; Faham S.; Yang D.; Whitelegge J. P.; Bowie J. U. (2004) The evolution of transmembrane helix kinks and the structural diversity of G protein-coupled receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 959–963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatakrishnan A. J.; Deupi X.; Lebon G.; Tate C. G.; Schertler G. F.; Babu M. M. (2013) Molecular signatures of G-protein-coupled receptors. Nature 494, 185–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heifetz A.; Morris G. B.; Biggin P. C.; Barker O.; Fryatt T.; Bentley J.; Hallett D.; Manikowski D.; Pal S.; Reifegerste R.; Slack M.; Law R. (2012) Study of human Orexin-1 and -2 -G-protein-coupled receptors with novel and published antagonists by modeling, molecular dynamics simulations, and site-directed mutagenesis. Biochemistry 51, 3178–3197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palczewski K.; Kumasaka T.; Hori T.; Behnke C. A.; Motoshima H.; Fox B. A.; Le Trong I.; Teller D. C.; Okada T.; Stenkamp R. E.; Yamamoto M.; Miyano M. (2000) Crystal structure of rhodopsin: A G protein-coupled receptor. Science 289, 739–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chien E. Y. T.; Liu W.; Zhao Q.; Katritch V.; Won Han G.; Hanson M. A.; Shi L.; Newman A. H.; Javitch J. A.; Cherezov V.; Stevens R. C. (2010) Structure of the human dopamine D3 receptor in complex with a D2/D3 selective antagonist. Science 330, 1091–1095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaakola V.-P.; Ijzerman A. P. (2010) The crystallographic structure of the human adenosine A2A receptor in a high-affinity antagonist-bound state: Implications for GPCR drug screening and design. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 20, 401–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherezov V.; Rosenbaum D. M.; Hanson M. A.; Rasmussen S. G. F.; Thian F. S.; Kobilka T. S.; Choi H.-J.; Kuhn P.; Weis W. I.; Kobilka B. K.; Stevens R. C. (2007) High-resolution crystal structure of an engineered human β2-adrenergic G protein-coupled receptor. Science 318, 1258–1265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courcot B.; Bridgeman A. J. (2011) Modeling the interactions between polyoxometalates and their environment. J. Comput. Chem. 32, 3143–3153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf M. G.; Hoefling M.; Aponte-Santamaría C.; Grubmüller H.; Groenhof G. (2010) g_membed: Efficient insertion of a membrane protein into an equilibrated lipid bilayer with minimal perturbation. J. Comput. Chem. 31, 2169–2174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess B.; Kutzner C.; van der Spoel D.; Lindahl E. (2008) GROMACS 4: Algorithms for highly efficient, load-balanced, and scalable molecular simuation. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 4, 435–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen W. L.; Maxwell D. S.; Tirado-Rives J. (1996) Development and testing of the OPLS all-atom force field on conformational energetics and properties of organic liquids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 118, 11225–11236. [Google Scholar]

- Kaminski G. A.; Friesner R. A.; Tirado-Rives J.; Jorgensen W. L. (2001) Evaluation and Reparametrization of the OPLS-AA Force Field for Proteins via Comparison with Accurate Quantum Chemical Calculations on Peptides. J. Phys. Chem. B 105, 6474–6487. [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen W. L.; Chandresekhar J.; Madura J. D.; Impey R. W.; Klein M. L. (1983) Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. J. Chem. Phys. 79, 926–935. [Google Scholar]

- Van Gunsteren W. F.; Berendsen H. J. C. (1988) A leap-frog algorithm for stochastic dynamics. Mol. Simul. 1, 173–185. [Google Scholar]

- Essman U.; Perera L.; Berkowitz M. L.; Darden T.; Lee H.; Pedersen L. G. (1995) A smooth particle mesh Ewald method. J. Chem. Phys. 103, 8577–8593. [Google Scholar]

- Hess B.; Bekker J.; Berendsen H. J. C.; Fraaije J. G. E. M. (1997) LINCS: A linear constraint solver for molecular simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 18, 1463–1472. [Google Scholar]

- Korb O.; Olsson T. S. G.; Bowden S. J.; Hall R. J.; Verdonk M. L.; Liebeschuetz J. W.; Cole J. C. (2012) Potential and limitations of ensemble docking. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 52, 1262–1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebeschuetz J.; Cole J.; Korb O. (2012) Pose prediction and virtual screening performance of GOLD scoring functions in a standardized test. J. Comput.-Aided Mol. Des. 26, 737–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman H. J.; Labute P. (2010) Pocket similarity: Are α carbons enough?. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 50, 1466–1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madabushi S.; Gross A. K.; Philippi A.; Meng E. C.; Wensel T. G.; Lichtarge O. (2004) Evolutionary trace of G protein-coupled receptors reveals clusters of residues that determine global and class-specific functions. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 8126–8132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez D.; Pineiro A.; Gutirrez-de-Teran H. (2011) Molecular dynamics simulations reveal insights into key structural elements of adenosine receptors. Biochemistry 50, 4194–4208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thepchatri P.; Eliseo T.; Cicero D. O.; Myles D.; Snyder J. P. (2007) Relationship among ligand conformations in solution, in the solid state, and at the HSP90 binding site: Geldanamycin and radicicol. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 3127–3134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hascall T.; Baik M. H.; Bridgewater B. M.; Shin J. H.; Churchill D. G.; Friesner R. A.; Parkin G. (2002) A non-classical hydrogen bond in the molybdenum arene complex [η6-C6H5C6H3(Ph)OH]Mo(PMe3)3: Evidence that hydrogen bonding facilitates oxidative addition of the O-H bond. Chem. Commun. 21, 2644–2645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed M. N. A.; Watts H. D.; Guo J.; Catchmark J. M.; Kubicki J. D. (2010) MP2, density functional theory, and molecular mechanical calculations of C–H···π and hydrogen bond interactions in a cellulose-binding module–cellulose model system. Carbohydr. Res. 345, 1741–1751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trzaskowski B.; Latek D.; Yuan S.; Ghoshdastider U.; Debinski A.; Filipek S. (2012) Action of molecular switches in GPCRs: Theoretical and experimental studies. Curr. Med. Chem. 19, 1090–1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kneissl B.; Mueller S. C.; Tautermann C. S.; Hildebrandt A. (2011) String kernels and high-quality data set for improved prediction of kinked helices in α-helical membrane proteins. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 51, 3017–3025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abrol R., Kim S.-K., Bray J. K., Trzaskowski B., and Goddard W. A. III (2013) Chapter two: Conformational ensemble view of G protein-coupled receptors and the effect of mutations and ligand binding. In Methods in Enzymology (Conn P. M., Ed.) pp 31–48, Academic Press, New York. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tate C. G. (2012) A crystal clear solution for determining G-protein-coupled receptor structures. Trends Biochem. Sci. 37, 343–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.