Abstract

Background: The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) has pioneered telemental health (TMH) with over 500,000 TMH encounters over the past decade. VA community-based outpatient clinics were established to improve accessibility of mental healthcare for rural Veterans. Despite these clinics clinics and increased availability of TMH, many rural Veterans have difficulty receiving mental healthcare, particularly psychotherapy. Materials and Methods: Twelve therapists participated in a pilot project using TMH technologies to improve mental healthcare service delivery to rural Veterans treated at six community clinics. Therapists completed online training, and study staff communicated with them monthly and clinical leaders every other month. Therapists completed two questionnaires: before training and 10 months later. This article describes barriers and facilitators to the implementation of the project, as well as therapists' knowledge, confidence, and motivation regarding TMH. Results: Two clinicians were offering telepsychotherapy after 10 months. At all six sites, unanticipated organizational constraints and administrative barriers delayed implementation; establishing organizational practices and therapists' motivation helped facilitate the process. Adopters of the project reported more positive views of the modality and did not worry about staffing, a concern of nonadopters. Conclusions: Despite barriers to implementation, lessons learned from this pilot project have led to improvements and changes in TMH processes. Results from the pilot showed that therapists providing telepsychotherapy had increased confidence, knowledge, and motivation. As TMH continues to expand, formalized decision-making with clinical leaders regarding project goals, better matching of therapists with this modality, and assessment of medical center and clinic readiness are recommended.

Key words: : military medicine, telehealth, telepsychiatry

Introduction

The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) has pioneered telemental health (TMH), including individual, family, and group therapies, medication management, patient education, and psychological testing.1 TMH within the VA has become widespread, with over 500,000 documented encounters over the past decade.2

TMH helps reach the over 40% of Veterans in rural communities, including returnees from Operations Enduring Freedom, Iraqi Freedom, and New Dawn.3 Rural mental healthcare is ideally provided through community-based outpatient clinics, established to bring medical care close to where Veterans reside. However, many rural Veterans encounter difficulty securing mental healthcare, particularly psychotherapy.

One solution is telepsychotherapy provided by clinicians with specialized mental health expertise. Research has found that telepsychotherapy can be successfully used in several therapeutic formats, has similar outcomes to face-to-face treatment, and is considered satisfactory by most patients and therapists.4 However, barriers to implementation include therapist reluctance, perceived patient discomfort, unfamiliarity with the modality, lack of time, safety concerns, and technological difficulties.5–9

The South Central Mental Illness Research, Education and Clinical Center, a virtual center within the South Central Veterans Integrated Service Network 16 dedicated to improving healthcare services to Veterans with mental illness, especially rural Veterans, initiated a pilot project to increase telepsychotherapy in the South Central area. Three medical centers participated to provide services to six clinics. The project used a FOCUS-PDSA model, a quality-improvement framework used by many healthcare organizations, to plan and evaluate interventions.10 Its goals were to improve access to telepsychotherapy at community clinics and identify facilitators and barriers to its implementation.

Participants and Procedure

Therapists completed required Web-based VA TMH training and also a 1-h live video presentation given by an experienced telepsychotherapist. Participating medical centers received two videoconferencing units. Project staff communicated with therapists at least monthly and clinical leaders every other month about progress. In addition, therapists completed two questionnaires. The first examined attitudes and knowledge regarding telepsychotherapy. The second assessed changes in attitudes and knowledge during the project and explored barriers and facilitators to implementation.

Measures

Two investigator-designed questionnaires were created. The 28-item pretraining questionnaire focused on knowledge, confidence, and motivation to provide telepsychotherapy, as well as attitudes about it. Ten questions collected demographic information. The second 35-item questionnaire, administered 10 months later, first asked, “Do you currently provide telepsychotherapy?” Those answering “yes” responded to 17 questions about their experience. All completed the remaining 18 questions about TMH implementation and their knowledge, confidence, and motivation to provide treatment.

Results

Participants

Twelve therapists volunteered to participate. Seven were psychologists (58%), three were social workers (25%), and two (17%) were from other backgrounds (counselor, vocational specialist). Eight (67%) were women, and four (33%) were men. Mean age was 44.6 years (±10.7). On average, they had been mental health clinicians for over 8 years, with more than 6 years for the VA.

Therapist Knowledge, Confidence, and Motivation Regarding TMH

Therapists were asked about their knowledge, confidence, and motivation regarding TMH. Adopters were more motivated than nonadopters to begin TMH. Training increased knowledge for both adopters and nonadopters. At project completion, adopters reported “excellent” knowledge of TMH, whereas nonadopters reported “good” knowledge. Similarly, those with hands-on experience conducting telepsychotherapy reported “excellent” confidence; nonadopters reported “good” confidence. Overall, adopters had more positive views of the modality from the beginning and did not worry about staffing, a concern of nonadopters, Adopters noted that “[TMH] is not as difficult or as disruptive as I thought it was going to be” and “….have been surprised how well Veterans have seemed to accept the telehealth approach.”

Barriers and Facilitators

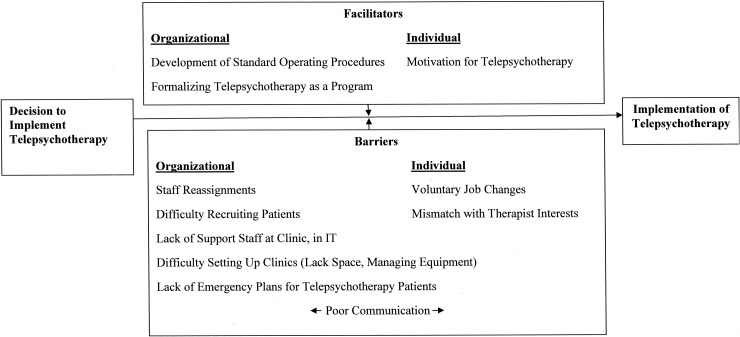

Two clinicians were offering telepsychotherapy after 10 months. Barriers were encountered at all sites, slowing implementation (Table 1). Unanticipated organizational constraints included limited space, misplaced equipment, lost work orders to install equipment, and difficulties setting up and supporting new clinics. Administrative barriers included inadequate staffing, delays in staff credentialing, poor communication from clinical leaders about priorities and workload, patient recruitment problems, and staff changes. Establishing organizational practices and therapist motivation helped facilitate implementation (Fig. 1) Participants had an opportunity to provide suggestions regarding the project. Nonadopters commented on implementation barriers, noting, “difficulties….are largely related to the clinical demands, staff shortages (mental health and clerical), scheduling problems, equipment failures…” and “clear goals, direction and support for individual providers would help [make] this more feasible.” An adopter suggested, “The novelty [of TMH] may enhance patients' interest, acting as a facilitator.” Finally, a nonadopter recommended other TMH alternatives: “…a greater need is for use of home units or use of encrypted Skype or other technology allowing for improved…access to care for rurally living Veterans who may not have the means to travel to and from the clinics.”

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Barriers to Implementation of Telemental Health

| QUESTION | ADOPTERS (N=2) | NONADOPTERS (N=8) |

|---|---|---|

| Access to TMH equipment has been/is difficult |

2.00±0.00 |

2.88±1.36 |

| Has been/continues to be difficult to locate office space to provide TMH |

3.50±0.71 |

2.75±1.28 |

| Lack of referrals and/or client disinterest inhibited implementation of TMH |

2.50±2.12 |

3.13±1.46 |

| There are/were problems setting up therapists' clinic |

2.00±1.41 |

3.50±1.20 |

| Staffing concerns limited therapists' ability to offer TMH |

2.50±2.12 |

2.88±1.13 |

| Credentialing process interfered with therapists' ability to offer TMH | 1.00±0.00 | 2.25±1.58 |

Data are mean±standard deviation values. Scores range from 1=strongly disagree to 5=strongly agree.

TMH, telemental health.

Fig. 1.

Barriers and facilitators of the telepsychotherapy pilot project. IT, information technology.

Discussion and Conclusions

The goals of this project were to improve access to telepsychotherapy to community clinics and identify facilitators and barriers to implementation. Only two clinicians provided telepsychotherapy. The very act of simply providing telepsychotherapy coincided with a rise in reported knowledge, confidence, and motivation.

Therapists and clinical leaders identified barriers to implementation. Unanticipated barriers were identified. In many cases, clinical leaders had not acknowledged telepsychotherapy as a priority. It appeared some had not considered therapist characteristics that might best fit with telepsychotherapy, despite investigators stressing this. Some therapists reported little interest in conducting telepsychotherapy, and many were unprepared for the effort necessary. Other unanticipated barriers resulted from slow credentialing processes whereby licensed therapists were unable to provide direct care independently until their training had been verified and delays in equipment installation. At one site, work orders were lost and had to be resubmitted several times before installation could occur. At another, telehealth equipment was mislabeled and lost for months. At some clinics, placement of equipment limited its usability or accessibility: one had the system in a room that was not soundproof. In future, we recommend formalized decision-making with clinical leaders regarding project goals, better matching of therapists with this modality, and assessing medical center and clinic readiness. We also suggest identifying more therapists per site to account for attrition and increasing frequency of communication with clinical leaders. Identifying and using TMH champions, as recommended by Gagnon et al.,9 could also facilitate adoption.

We are now expanding TMH in partnership with the network. This new project, funded by the VA Central Office, establishes evidence-based TMH for posttraumatic stress disorder at seven medical centers. Although barriers to implementation remain, this project has moved faster and more successfully than the pilot study, perhaps partly because of changes in TMH processes. Establishing facility telehealth committees to manage equipment and connectivity demands, and support resources to deliver care remotely, and adding telehealth coordinators to help troubleshoot issues at the clinics have been significant. Lessons learned from the pilot helped project staff target processes earlier identified as barriers.

Implementing telepsychotherapy has been met with growing success. As we continue to improve and expand TMH, we expect it to help provide mental health services for rural residents, eventually bringing services into patients' homes.

Acknowledgments

This work was partly supported by the Office of Research and Development, Veterans Health Administration, Department of Veterans Affairs, and the Houston VA Health Services Research & Development Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness, and Safety (grant CIN 13-413) and the South Central Mental Illness Research, Education and Clinical Center.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Deen TL, Godleski L, Fortney JC. A description of telemental health services provided by the Veterans Health Administration in 2006–2010. Psychiatr Serv 2012;63:1131–1133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Godleski L, Darkins A, Peters J. Outcomes of 98,609 U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs patients enrolled in telemental health services, 2006–2010. Psychiatr Serv 2012;63:383–385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morland LA, Greene CJ, Rosen C, Mauldin PD, Frueh BC. Issues in the design of a randomized noninferiority clinical trial of telemental health psychotherapy for rural combat veterans with PTSD. Contemp Clin Trials 2009;30:513–522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Backhaus A, Agha Z, Maglione ML, Repp A, Ross B, Zuest D, Rice-Thorp NM, Lohr J, Thorp SR. Videoconferencing psychotherapy: A systematic review. Psychol Serv 2012;9:111–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barak A, Boniel-Nissim M, Suler J. Fostering empowerment in online support groups. Comput Hum Behav 2008;24:1867–1883 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bee PE, Bower P, Lovell K, Gilbody S, Richards D, Gask L, Roach R. Psychotherapy mediated by remote communication technologies: A meta-analytic review. BMC Psychiatry 2008;8:60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith HA, Allison RA. Telemental health: Delivering mental health care at a distance. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 1998. Available at http://nebhands.nebraska.edu/files/telemental%20health%20systems.pdf (last accessed April23, 2013)

- 8.Tuerk PW, Yoder M, Ruggiero KJ, Gros DF, Acierno R. A pilot study of prolonged exposure therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder delivered via telehealth technology. J Trauma Stress 2010;23:116–123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gagnon MP, Desmartis M, Labrecque M, Car J, Pagliari C, Pluye P, Frémont P, Gagnon J, Tremblay N, Légaré F. Systematic review of factors influencing the adoption of information and communication technologies by healthcare professionals. J Med Syst 2012;36:241–277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schwarz M, Landis SE, Rowe JE. A team approach to quality improvement. Fam Pract Manag 1999;6.4:25–30 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]