Abstract

Background: HABITS for Life was a 3-year initiative to broadly deliver a statewide biometric and retinal screening program via a mobile unit throughout New Mexico at no charge to participants. The program goal—to identify health risk and improve population health status—was tested over a 3-year period. Value to participants and impact to the healthcare system were measured to quantify impact and value of investing in prevention at the community level. Materials and Methods: We used the Mobile Health Map Return-on-Investment Calculator, a mobile screening unit, biometric screening, retinography, and community coordination. Our systems included satellite, DSL, and 3G connectivity, a Tanita® (Arlington Heights, IL) automated body mass index–measuring scale, the Cholestec® (Alere™, Waltham, MA) system for biomarkers and glycosylated hemoglobin, a Canon (Melville, NY) CR-1 Mark II camera, and the Picture Archiving Communication System. Results: In this report for the fiscal year 2011 time frame, 6,426 individuals received biometric screening, and 5,219 received retinal screening. A 15:1 return on investment was calculated; this excluded retinal screening for the under-65 year olds, estimated at $10 million in quality-adjusted life years saved. Statistically significant improvement in health status evidenced by sequential screening included a decrease in total cholesterol level (p=0.002) (n=308) and an increase in high-density lipoprotein level after the first and second screening (p=0.02 andp=0.01, respectively), but a decrease in mean random glucose level was not statistically significant (p=0.62). Retinal results indicate 28.4% (n=1,482) with a positive/abnormal finding, of which 1.79% (n=93) required immediate referral for sight-threatening retinopathy and 27% (n=1,389) required follow-up of from 3 months to 1 year. Conclusions: Screening programs are cost-effective and provide value in preventive health efforts. Broad use of screening programs should be considered in healthcare redesign efforts. Community-based screening is an effective strategy to identify health risk, improve access, provide motivation to change health habits, and improve physical status while returning significant value.

Key words: : business administration/economics, telemedicine, ophthalmology, extreme environments, information management

Introduction

The concept of the Health Access and Better Impact via Technology and Service (HABITS) for Life program began as a joint initiative between the UnitedHealth Group and Project HOPE in 2009 and ended December 31, 2012. The program sought to answer the question of what the impact of accessible and routine screening at the community level could have on personal health status and to identify value by quantifying the results for participants and for the healthcare system as a whole. All services were provided free of charge.

The goal of broad-based community screening programs includes evaluating whether screening services help to motivate people to help themselves. Does access to our personal data that is routine and easily accessed help us stay healthy? Does this type of service delay or prevent the development of chronic disease? The long-term impact of population-based screening as a strategy to prevent chronic diseases such as diabetes and heart disease will take time to answer.

The impact of a statewide screening service to identify and prevent chronic disease has not been measured, and a focused national effort to screen for undiagnosed diabetes does not exist.1 It is difficult to quantify the benefits as they accrue to multiple stakeholders. However, the potential of mobile screening as an integrated player in the healthcare system and the value of investing in prevention are potentially enormous!

Internationally, population-based screening has been successful and returned good value.2–5 The U.S. healthcare system, with its multiplicity of providers and payment methods, creates a barrier to creating and measuring this type of program as the benefits accrue to multiple stakeholders. A problem in measuring the value of a statewide population screening program is that outcomes data are not easily available for the uninsured as well as the insured population. Therefore, no single stakeholder feels the responsibility of full ownership. Hospitals, Departments of Health, Medicare, Medicaid, and insurers all receive value within the context of their business model. As an example, the New Mexico Department of Health statistics department identified one county with 4,500 hospitalizations with diabetes as a primary diagnosis in 2008–2009. Half of those were there because of a diagnosis for an ambulatory care condition that could have potentially been preventable with access to primary care. Hospitalizations for diabetes as the primary diagnosis totaled $5.25 million. Hospitalizations for ambulatory care conditions totaled nearly $2.36 million, and these costs may have been avoided with earlier diagnosis.6 Anxiety and emergency care may also have been avoided with earlier diagnosis. The HABITS for Life screening program identified a 7% rate of undiagnosed diabetes within the same county after implementing the screening program, and participants were sent to primary care and treated earlier. Cost savings could be apportioned over time; however, data are not yet available.

A focused analysis of the relative value of mobile health screening models is just being developed in the United States. In 2009, collaboration between the Family Van, a research team at Harvard Medical School, and Mobile Health Clinics Association7 developed an empirical method to determine the efficacy of mobile healthcare. They created the Mobile Health Clinic Return-on-Investment (ROI) Calculator.8 In this study we have adapted their empirical method and estimated the relative value of the HABITS for Life program.

Background

The U.S. healthcare system is undergoing a fundamental change that is being precipitated in part by the aging population, the increase in age-related chronic diseases, and the cost of providing care and services. Information and communication technologies are being enabled to provide solutions in the healthcare sector and are expected to contribute significantly in future years. A key factor often overlooked, in decreasing the burden of disease on the healthcare system, is prevention or delay in developing age-related diseases through accessible and timely identification of health risk, at the individual and community levels. Linking technology to prevention and identifying personal health risk at the community level using a mobile health unit have been the thrust of the HABITS for Life screening program.

Currently, preventive health represents only 5–10% of U.S. healthcare expenditure, and in a recent study the United States ranked eighth among 23 Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development member countries in the percentage of total healthcare spending reported for prevention and public health services.9 In the United States, the effect on population health of broad-based mobile screening has not yet been measured1; however, it deserves consideration by insurers and the Federal and state entities tasked with improving health.

Prevention requires personal information identifying health risk be timely and accessible and provide value to the person and healthcare system. The New Mexico medical community and Department of Health outreach services spend time and resources to alert the public to the necessity of identifying health risk and the need for routine screening. What was missing was access to these services in the communities and Colonias that make up New Mexico. The strategy of providing community-oriented screening can give people knowledge of their own health status. Early indicators of health risk are identified, at a time frame that allows action to prevent or delay the onset of diabetes and heart and eye disease. In New Mexico, diabetes is an epidemic, heart disease remains the number one cause of death, and diabetic retinopathy is a leading cause of blindness. In fact, diabetic retinopathy is the number one cause of blindness in the United States.10–13

Most people acknowledge they know they should have a health screening and check their eyes, but the barriers are a lack of time, easy access, and cost. This is true for the insured working population as well as the underserved and uninsured. The personal knowledge of where you are starting with biometric indicators is a necessary first step to improving health, and our results show that screening does provide needed motivation to change health habits. Mobile screening linked to the health delivery system brings prevention to the community level and provides ease of access—Saturday morning at the grocery store, after church on a Sunday, in community centers, at special events, at the doctor's office, and in the workplace.

Expanding mobile and community-based screening services is one solution to providing timely and accessible prevention services that provide value to the person and healthcare system.

Materials and Methods

The HABITS for Life program was provided at no cost to participants or organizations. A mobile health unit provided access throughout New Mexico. The mobile unit, dubbed the “HOPEmobile,” provided connectivity (satellite, DSL, and 3G) and a self-contained mobile site to give biometric and retinal screenings. Connectivity allows streaming of retinal images when the retinographer identifies a potentially emergency situation. Training was provided to staff in all aspects of the program and included retinal photography, biometric testing, and counseling. Process and event logistics are managed by Project HOPE staff and scheduled in collaboration with partnering organizations. Promotoras, radio, television, and local signage are used to raise awareness about the upcoming events. Information and communication technologies connections to the clinic electronic health record system were used in some venues and were offered to clinics during the planning process. Coordination with worksite wellness events included access to personal health accounts via the Internet through the HOPEmobile connections.

At the time of the screening, an anonymous registration questionnaire was completed, and a barcode was distributed. Participants were asked to keep the barcode and bring it back when they return for subsequent screenings. No personally identifiable information was gathered. Informed consent was obtained for retinal screening.

Biometric screening was done by licensed staff (RNs and LVNs) and community health workers. On-site counseling is provided by trained nursing staff. Materials and counseling were provided in both English and Spanish. Videos promoting healthy habits, stress reduction, and information about diabetes and heart disease are played on the mobile unit while screenings are in progress and outside the unit for people waiting. This provides an opportunity to inform the public and answer questions.

Venues included Federally Qualified Health Center partner sites, worksite wellness, special events, health fairs, senior centers, and faith-based programs. The strategy was to evaluate venues for appropriateness and to reach further into the communities around the state. Health fairs and special events included games for children (Wii™ [Nintendo of America, Redmond, WA] interactive videos) and educational games related to healthy eating habits and physical activity. Community-based events are held in conjunction with primary clinics. The clinics serve as the primary home and referral source for needed services. Screenings in the Colonias in Southern New Mexico were facilitated by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and held in local community centers. Faith-based programs included community outreach by churches and screening events on Sunday after church services. Several events were held at Senior Centers in Albuquerque and Las Cruces.

Improvements in health status were calculated for sequential screening results of returning participants.

The HABITS for Life program ROI was calculated for the time frame July 1, 2011–June 30, 2012. This represents 1 year of full program operations in collaboration with Federal Qualified Health Centers around New Mexico. No tool for the relative value of mobile health screening models has been developed. Recently, the Family Van, a mobile clinic research team at Harvard Medical School, in partnership with Mobile Health Clinics Association implemented a pilot project to quantify the value of mobile clinic screening and prevention programs. (“This average ROI is an estimate is based on calculations made on programs that best fit the assumptions and characteristics of the initial published paper. Our research team is working to expand the algorithm in order to more accurately calculate the ROI for specialty vans, pediatric vans, dental vans and rural programs.”14) Although this prototype is still immature, it yields an approximation of the value of these programs. The algorithm for the ROI Calculator15 was designed to answer the value proposition quantified in terms of quality-adjusted life years saved (QALYS) and estimated emergency department (ED) expenditures avoided.8 The Partnership for Prevention guidelines were used to develop the relative value of screening models. Retinal screening is included for the 65 years of age and older population.

The value of screening services for eye disease has not been quantified in the under-65-year-old population. Consequently, the current tool for calculating ROI does not include the value of retinal screening for those less than 65 years of age. The following methodology was applied in order to calculate the ROI for the 18–64-year-old population, who received retinal screening and had positive findings. According to a systemic review of retinal screening,16 a QALYS value range is U.S. $6,900–$116,800 saved. A separate calculation using the most conservative estimate ($6,900) was used to approximate the value in QALYS for this age range.

The ROI Calculator included estimated cost saving realized from the avoidance of unnecessary ED visits. Although the tool is weighted for ED visits on a typical mobile unit, the majority of those programs provide consultative clinical services and may experience a higher number of ED visits than the HOPEmobile program. We have not captured the number of people sent to the ED as a result of the screenings, and this would need to be further evaluated.

The relative value of mobile health clinic services is equal to the annual projected ED costs avoided plus the value of potential life years saved from the services provided. The ROI ratio equals the relative value of the mobile health clinic services divided by the annual cost to run the mobile health clinic. (Note that the appropriateness of this algorithm for any specific clinic depends on the characteristics of the clinic. However, as an approximation, this analysis adds a quantifiable and logical dimension.)

MATERIALS

Technology used for screening included a Tanita® (Arlington Heights, IL) scale for automated measurement of body mass index. The Cholestec® (Alere™, Waltham, MA) system was used for levels of biomarkers and glycosylated hemoglobin (A1C). The retinography technology suite included a non-mydriatic Canon (Melville, NY) CR-1 Mark II retinal camera and a Food and Drug Administration–cleared, Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act–compliant Picture Archiving Communication System. ROI calculation used the Mobile Health Map.org ROI Calculator.13

Services were provided via a mobile health screening unit and included body mass index (a ratio of muscle mass to fat), blood pressure, height, weight, cholesterol and its components, blood sugar/glucose, and A1C. A1C represents a 3-month average blood glucose level. A1C levels are diagnostic for diabetes and prediabetes. All screenings are Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments waived.

Results

Biometric screening was provided to 6,426 New Mexicans in 31 of the 33 counties. The population was 35% male and 65% female. Forty-eight percent self-identified as Latino, 22% as white, 11% as Native American, 2% as African American, and 1% as Asian/Pacific Islander; 9% chose not to identify (other).

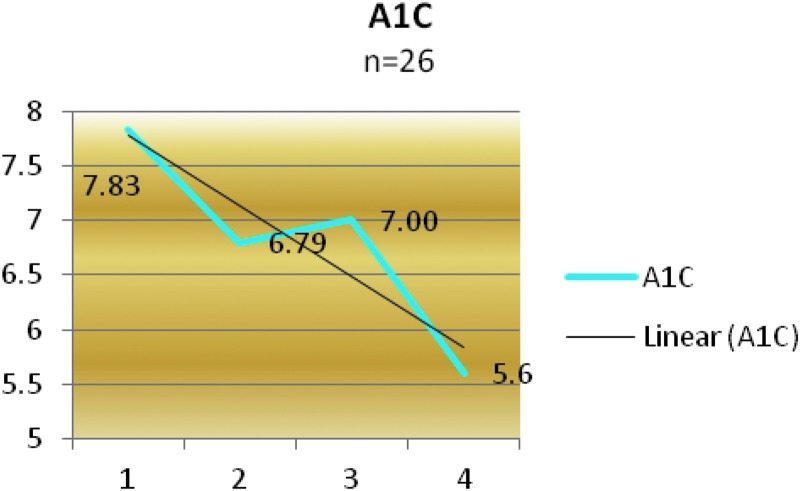

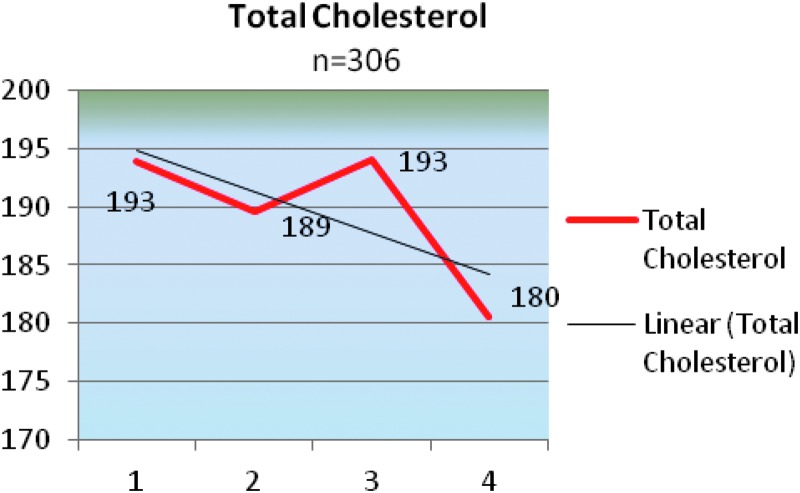

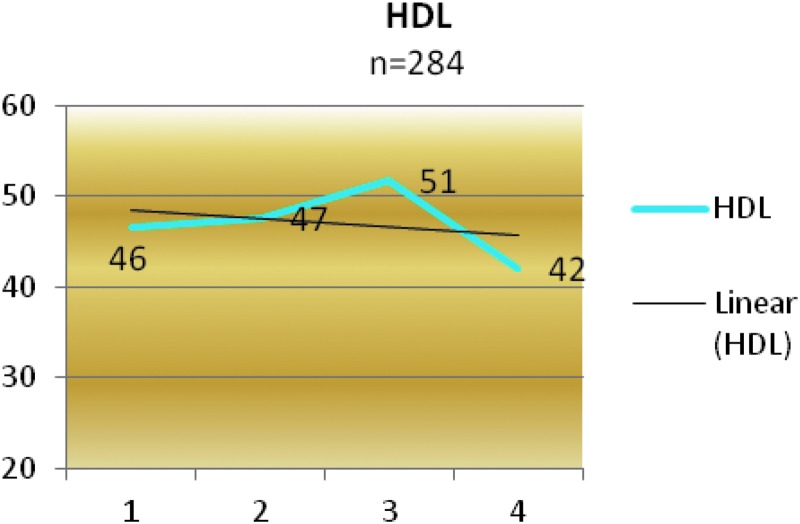

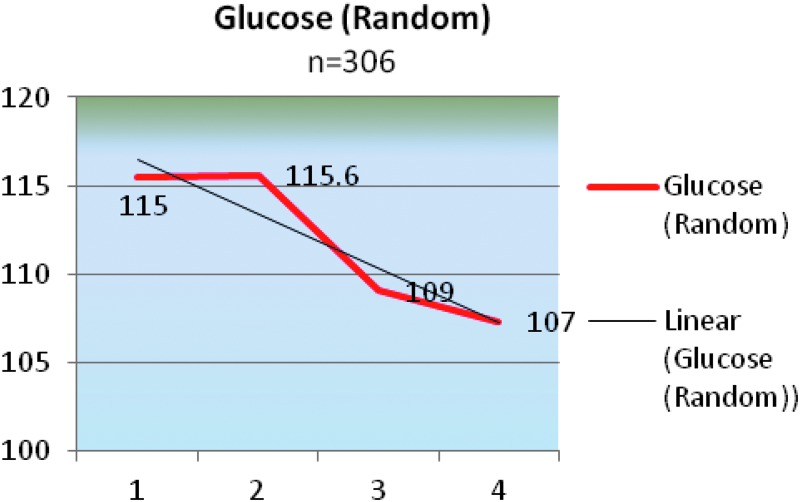

The total number of participants who returned with the barcode for repeat screenings is was 308 (Table 1). Private communication with screenees indicates that many more participated in repeat screenings but lost the barcode and were unable to be tracked. Other methods of identification such as palm print technology would alleviate the loss of captured information. Graphic results are illustrated in Figures 1–4 for A1C, cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein, and random blood glucose levels, respectively. The number in each follow-up visit will vary as participants did not repeat all tests, and numbers are noted in the applicable figure.

Table 1.

Return Participants' Sequential Screening

| BASELINE TOTAL N=308 | 2ND | 3RD | 4TH | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1C |

26 |

61 |

17 |

1 |

| Glucose |

306 |

299 |

58 |

12 |

| Cholesterol |

306 |

299 |

58 |

12 |

| HDL | 284 | 294 | 57 | 12 |

A1C, glycosylated hemoglobin; HDL, high-density lipoprotein.

Fig. 1.

Return participants' glycosylated hemoglobin (A1C) levels.

Fig. 2.

Return participants' total cholesterol levels.

Fig. 3.

Return participants' high-density lipoprotein (HDL) levels.

Fig. 4.

Return participants' glucose (random) levels.

There was a statistically significant decrease in total cholesterol between the first and second screening (p=0.002) and an increase in high-density lipoprotein level between the first and second screening (p=0.02 and p=0.01, respectively). The group mean for random glucose level across time showed a decrease but was not statistically significant (p=0.62). Results indicate that access to screening has motivated people and that they are working on their health.

Retinal screening was provided to 5,219 individuals. Of these, 28.4% (n=1,482) had a positive or abnormal finding and required referral to a specialist. Of the 17% who had diagnosed diabetes, 23% had positive findings. Ninety-three people (1.79%) required immediate referral to an ophthalmologist for sight-threatening retinopathy. Twenty-seven percent required follow-up within a 3-month to 1-year time frame.

Based on our service data, the ROI for the HABITS for Life program was calculated as $15 for every $1 invested in the program (15:1). This includes the operational cost supported by UnitedHealth Group for the mobile unit as well as programmatic cost (direct and indirect) (Tables 2 and 3). All services were provided free of charge to participants. Additionally, there were 4,425 retinal screenings for 18–64 year olds completed; of these, 1,461 had positive findings. We applied the conservative end of the range identified in the literature16 for retinal savings, and although this is not specific to this age group, it identifies that considerable savings could be apportioned based on the identification of disease in this population ($6,900×$1,461=$10,080,900). Additional cost valuation is needed in this age range.

Table 2.

Return on Investment Calculations

| FACTOR | VALUE |

|---|---|

| Total number of visitors |

6,804 |

| Total number of new visitors |

6,426 |

| % of first-time visits |

94% |

| Average cost per visit |

$266 |

| Annual projected cost avoided | $983,450 |

Table 3.

Return on Investment Measures and Results

| SERVICES DELIVERED | TOTAL NUMBER OF QALYSa | ESTIMATED VALUE OF QALYSa | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hypertension screening and treatment |

354 |

29.9484 |

$2,096,388 |

| Vision screening for adults >65 years old |

650 |

17.184375 |

$1,202,906 |

| Cholesterol screening and treatment |

1,370 |

115.902 |

$8,113,140 |

| Obesity screening |

6,426 |

169.887375 |

$11,892,116 |

| Cholesterol screening of high-risk individuals |

478 |

1.68495 |

$117,947 |

| Diabetes screening |

6,426 |

22.65165 |

$1,585,616 |

| Diet counseling |

6,426 |

22.65165 |

$1,585,616 |

| Total | 22,130 | 379.9104 | $26,593,728 |

The return on investment ratio was 15:1.

The overall goal of the analysis was to develop a ranking of services with fair to good evidence of effectiveness, excluding services with insufficient evidence or evidence of ineffectiveness. The ranking was designed to assist decision makers at multiple levels: clinicians and their patients can use the ranking to identify which among these recommended services to emphasize, and care delivery leaders should find the ranking valuable as they make choices about the design of prevention programs.

QALYS, quality of life years saved.

Discussion

The results of the HABITS for Life program both in personal health improvement and in ROI indicate that, given the right approach, context, and implementation, the benefits from an effective prevention investment are significant. Once the development and implementation phases have been successfully operationalized, the value of these benefits will only increase. Annual costs are stable, and net benefit should continue to grow. Screening programs implemented via mobile health units can contribute to satisfying the population's need for better access to needed personal information to improve health status and provide value to all stakeholders. Services can be operationalized in rural and frontier areas as well as in inner city populations, as needed, and moved with changing demographics over time.

The strategy to provide personal information in a routine and accessible manner through mobile screening services is one that deserves consideration by insurers as well as Federal and state entities tasked with improving health. Community-level broad-based screening is cost-effective even when provided free of charge, as the HABITS for Life program illustrates. The public and healthcare system will receive a high return over time on such an investment, as will individuals, by delaying or preventing the development of chronic diseases. The HABITS for Life program results have demonstrated that people will work on their health and that screening can provide the needed motivation. The program has brought access and personal health information to the people of New Mexico in a way that is actionable and easy to access. State-based consortiums that include all stakeholders could be leveraged to provide ongoing funding for this type of program.

Acknowledgments

Program funding was provided by UnitedHealth Group. We thank members of our Advisory Board: Jeannine M. Rivet, Executive Vice-President, UnitedHealth Group; Mark Gennerman, Vice-President Collaborative Care; Kevin Kandalaft, Executive Director, UnitedHealth Group New Mexico; William Orr, MD, Medical Director, Evercare New Mexico; Kathryn Rubin, Vice-President, Social Responsibility; Jason Goux, Implementation Director, Collaborative Care; Will Shanley, Public Relations, UnitedHealth Group; and Mike Evans, CEO, Optum Health. This program would not have been possible without our partner organizations: VisionQuest-Biomedical LLC; Presbyterian Medical Services (Federally Qualified Health Center) staff and Laurence Lyons, MD, CMO, PMS; Doña Ana County Department of Health and Human Services staff; Sylvia Sierra, Director, Department of Health and Human Services; New Mexico Department of Health; De Baca Family Practice Clinic; Spirit Mission; and University of New Mexico. We are grateful to the organizations that have provided materials and additional funding for the HABITS for Life program, including Walgreens Pharmacy, Johnson & Johnson, Oak Tree International Holdings, Hologic, Inc., and LABSCO. We thank Nancy E. Oriol, MD, Dean of Students, Harvard University, for editorial review and comments.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Harris MI, Modan M. Screening for NIDDM: Why is there no national program? Diabetes Care 1994;17:440–444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Policy brief screening in Europe—World Health Organization Available at www.euro.who.int/document/e88698.pdf (last accessed December3, 2012)

- 3.Leiter LA, Barr A, Bélanger A, Lubin S, Ross SA, Tildesley HD, Fontaine N. Diabetes Screening in Canada (DIASCAN) Study: Prevalence of undiagnosed diabetes and glucose intolerance in family physician offices. Diabetes Care 2001;24:1038–1043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.UK National Screening Committee Criteria for appraising the viability, effectiveness and appropriateness of a screening programme. 2009. Available at www.screening.nhs.uk/criteria (last accessed December15, 2012)

- 5.Screening in England 2011–2012 Annual Report. Available at www.screening.nhs.uk/publications#fileid14375 (last accessed December15, 2012)

- 6.Scharma T. New Mexico Department of Health, Region 3. OCAPE, NMHDDS, non-Federal hospital 2008–2009 report. Albuquerque: New Mexico Department of Health, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mobile Health Clinics Association www.mobilehealthclinicsnetwork.org (last accessed November11, 2012)

- 8.Oriol NE, Cote PJ, Vavasis AP, Bennet J, DeLorenzo D, Blanc P, Kohane I. Calculating the return on investment of mobile healthcare. BMC Med 2009;7:27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.U.S. Government Accountability Office Preventive health activities: Available information on Federal spending, cost savings, and international comparisons has limitations. Report number GAO-13-49. Available at www.gao.gov/products/GAO-13-49 (last accessed December6, 2012)

- 10.National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Injury prevention and control: Data & statistics (WISQARS™). 2007. Available at www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/index.html (accessed November10, 2011)

- 11.New Mexico selected health statistics annual report for 2006 Santa Fe: Bureau of Vital Records and Health Statistics, New Mexico Department of Health, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Diabetic retinopathy occurs in pre-diabetes NIH News. June12, 2005. Available at www.nih.gov/news/pr/jun2005/niddk-12.htm (last accessed December2, 2012)

- 13.American Diabetes Association Diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes Care 2002;25(Suppl 1):S90–S93 Available at http://care.diabetesjournals.org/content/25/suppl_1/s90.full (last accessed November18, 2011) [Google Scholar]

- 14.Available at www.mobilehealthmap.org/explanation.html (last accessed October23, 2012)

- 15.Mobile Health Map.org ROI tool Available at www.mobilehealthmap.org/roi.php (last accessed October23, 2012)

- 16.Li R, Zhang P, Barker LE, Chowdhury FM, Zhang X. Cost-effectiveness of interventions to prevent and control diabetes mellitus: A systematic review. Diabetes Care 2010;33:1872–1894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]