Abstract

Patient outcomes are variable following severe traumatic brain injury (TBI); however, the biological underpinnings explaining this variability are unclear. Mitochondrial dysfunction after TBI is well documented, particularly in animal studies. The aim of this study was to investigate the role of mitochondrial polymorphisms on mitochondrial function and patient outcomes out to 1 year after a severe TBI in a human adult population. The Human MitoChip V2.0 was used to evaluate mitochondrial variants in an initial set of n=136 subjects. SNPs found to be significantly associated with patient outcomes [Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS), Neurobehavioral Rating Scale (NRS), Disability Rating Scale (DRS), in-hospital mortality, and hospital length of stay] or neurochemical level (lactate:pyruvate ratio from cerebrospinal fluid) were further evaluated in an expanded sample of n=336 subjects. A10398G was associated with DRS at 6 and 12 months (p=0.02) and a significant time by SNP interaction for DRS was found (p=0.0013). The A10398 allele was associated with greater disability over time. There was a T195C by sex interaction for GOS (p=0.03) with the T195 allele associated with poorer outcomes in females. This is consistent with our findings that the T195 allele was associated with mitochondrial dysfunction (p=0.01), but only in females. This is the first study associating mitochondrial DNA variation with both mitochondrial function and neurobehavioral outcomes after TBI in humans. Our findings indicate that mitochondrial DNA variation may impact patient outcomes after a TBI potentially by influencing mitochondrial function, and that sex of the patient may be important in evaluating these associations in future studies.

Key words: : brain injury, mitochondria, outcome, polymorphism, TBI

Introduction

Approximately 1.7 million Americans sustain a traumatic brain injury (TBI) every year, and it is estimated that 5.3 million Americans currently live with complications directly related to these injuries.1,2 These approximations do not include TBIs sustained during active military duty. Survivors of TBI often face chronic complications that interfere with daily activities and health related quality of life; however there is variability in the incidence and severity of these complications.3–7

Mitochondria are organelles within the cytoplasm of eukaryotic cells that house their own genome and are responsible for energy production to sustain the cell through oxidative metabolism to produce adenosine triphosphate (ATP), the major energy-carrying molecule in cells.8 The entire human mitochondrial genome has been sequenced and houses genes necessary for normal cellular functioning. A normal mitochondrial genome consists of 16,569 nucleotides and houses thirteen genes that are involved in the respiratory chain/oxidative phosphorylation system.9 Nuclear genes encode many proteins involved with cellular respiration; however, a normal functioning electron transport chain requires proteins specifically encoded by the mitochondrial. NADH dehydrogenase (ND) is an enzyme that catalyzes the oxidation of NADH and is involved in the first steps of the electron transport chain of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation. The ND genes of the mitochondria code for subunits of respiratory complex I of the electron transport chain. Complex II is encoded entirely by nuclear genes. Cytochrome b (cyt b) is the second enzyme in the electron transport chain, is encoded by the mitochondrial genome, and is involved in respiratory complex III. Cytochrome oxidase (CO) is an enzyme that functions by transferring electrons from cytochromes to oxygen, and is the third enzyme in the electron transport chain. CO subunits are encoded by the mitochondrial genome and are involved in respiratory complex IV. ATP synthase (A6 and A8) are the two mitochondrial-encoded subunits of respiratory complex V.9

The literature continues to build in support of mitochondrial dysfunction post-TBI with the majority of support coming from animal studies. Energy metabolism in the brain is abnormal following TBI, demonstrated by a decline in ATP production at a time when energy requirements increase in both rats and humans.10–12 Decreased ATP production 10,13–15 and increased lactate accumulation16 are hallmarks of mitochondrial dysfunction and have been well documented following TBI in rats. Also, support that mitochondrial dysfunction precedes neuronal loss after TBI has been demonstrated in animal models of TBI,17 providing further evidence that a therapeutic window may exist for intervention, and that focusing the intervention on the mitochondria has potential to reduce neuronal loss and reduce the incidence or severity of complications after TBI. Additionally, therapeutics that target mitochondrial function post-TBI are gaining momentum and have shown promise in human clinical trials. One such drug is cyclosporin A, whose target is the mitochondria, with the ultimate effect on prevention of mitochondrial dysfunction. Dosing and safety of cyclosporin A post-TBI has been evaluated in humans,18,19 and recent promising results for safety and efficacy in Phase II trials have been published.20

The role of the mitochondria post-TBI and the variability in outcomes attained by individuals who have had a TBI led to our hypothesis that variability in the mitochondrial genome may play a role in initial response to injury and impact long term outcomes attained post-TBI. To address this hypothesis, we investigated the role of mitochondrial DNA polymorphisms on both mitochondrial function, as well as patient outcomes out to 1 year after a severe TBI in a human adult population.

Methods

Population

This study was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects or next of kin. Subjects were recruited through the Brain Trauma Research Center (BTRC) at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC). Subjects were eligible for this study if they were admitted to the neuro intensive care unit of the UPMC-Presbyterian Hospital as a consequence of a severe traumatic brain injury [hospital-admission Glasgow Coma Score (GCS) ≤8 prior to the administration of paralytics or sedatives], aged 16 to 80 years, had cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) draining via external ventricular drain as standard of care, were not brain dead, and did not have a penetrating head injury. Informed consent included collection of genetic material for use in genomic studies, as well as withdrawal and use of CSF for scientific inquiry.

Two-stage genotype data collection

DNA was extracted from one of two sources. The preferred source for DNA was from whole blood (10 mL). DNA was extracted by centrifuging the blood, removing the white cells, and extracting DNA from the white cells using a simple salting out procedure.21 The secondary source for DNA was from excess CSF collected into the ventriculostomy bag that would otherwise have been discarded. DNA from the CSF (2 mL) was extracted using the manufacturer's instructions for the Qiamp Midi kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). All DNA was stored in 1X TE buffer at 4°C.

This project used a multistage design. The first stage of investigation examined single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) spanning the entire mitochondrial genome; assessed using the GeneChip Human Mitochondrial Resequencing Array 2.0 (MitoChip)22 and scanned using the GeneChip Scanner 7G, and images analyzed and sequence information determined using Affymetrix GSeq (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA) for 136 subjects. Only arrays and SNPs that demonstrated a ≥95% call rate passed quality control measures and were considered for subsequent analyses. The second stage of investigation focused on those SNPs from the first stage that were significantly associated with outcomes, neurochemical levels, or both, in 336 subjects that included the original 136 to avoid issues related to data generation across multiple platforms. Custom TaqMan® allele discrimination assays were designed for T195C, T4216C, and A4917G, and RFLP analysis was used for A10398G following design failure for a TaqMan® allele discrimination assay. Primer sequences, probe sequences, and experimental conditions are presented in Table 1. Quality control measures for evaluation of these four mitochondrial SNPs included exceeding 95% call rate, inclusion of duplicates across plates, and independent blinded double calls of data and discrepancies reconciled by evaluation of raw data or regenotyping of sample.

Table 1.

Primer, Probe Sequences, Experimental Conditions for Stage Two Genotyping

| SNP | F PRIMER | R PRIMER | PROBE | ANN TEMP | ENZ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T195C |

GCCTCATCCTATTATTTATCGCACCTA |

TGCAGACATTCAATTGTTATTATTATGTCCTACA |

CAGGCGAACATAC[C/T]TACTAA |

60°C1 |

NA |

| T4216C |

CACCTCCTATGAAAAAACTTCCTACCA |

GGAATGCTGGAGATTGTAATGGGTAT |

AGCATTACTTATATGA[T/C]ATGTCTC |

58°C2 |

NA |

| A4917G |

GCCTGCTTCTTCTCACATGACAA |

CAACTGCCTGCTATGATGGATAAGA |

CTCCCTCACTA[A/G]ACGTAAG |

60°C1 |

NA |

| A10398G | ACCCCTACCATGAGCCCTAC | GGAGTGGGTGTTGAGGGTTA | NA | 58°C | DdeI |

Normal Taqman PCR protocol used; 2long Taqman PCR protocol used: difference from normal condition is annealing at a lower temperature for 1 min 30 sec instead of 1 min, and cycling 50 times instead of the normal 40; NA,not applicable.

Functional and neurobehavioral evaluations

Outcome evaluations were determined at 3, 6, and 12 months after TBI by a technician under the direction of a neuropsychologist who is a member of the clinical staff of the BTRC. The primary outcomes of interest for this study were Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS), Neurobehavioral Rating Scale (NRS), Disability Rating Scale (DRS), in-hospital mortality, and hospital length of stay.

The GOS is a clinical observation scale specifically designed to measure outcomes after severe TBI and complements the GCS. GOS has five categories: 1=death, 2=persistent vegetative state, 3=severe disability, 4=moderate disability, 5=good recovery. The ratings reflect the patient's general independence in daily functioning as determined by observation and/or review of medical records. Inter-rater reliability has been reported at 78% with a weighted kappa coefficient of 0.85. Validity of the GOS has been supported by high correlation with severity of illness, as well as other measures of function such as the DRS.23–25

The NRS measures neurobehavioral changes after a TBI using a brief structured interview coupled with the patient's performance on selected cognitive tasks. Objective information is provided regarding orientation and memory, delayed recall, common knowledge, focused attention, and information processing ability. The NRS also provides information regarding the patient's attitude toward care providers, capacity for self-insight, while at the same time rating the patient for alertness, distractibility, intrusion of irrelevant material, coherence of conversation, physical and verbal signs of anxiety, tension, agitation, mood disturbances, and motor problems. The NRS has been shown to be a valid and reliable instrument to quantify both behavioral symptoms and gross cognitive changes after TBI. The NRS has an average inter-rater reliability of 74.3% and average kappa statistics of 0.40.26 Because NRS requires an individual to be alive and able to complete the assessment (GOS 1 and 2 not included), the sample size for NRS analyses were n=95 at 3 months, n=95 at 6 months, and n=79 at 12 months.

The DRS is a clinical observation scale that evaluates levels of recovery by rating the following domains of functional ability: eye opening; ability to communicate; motor responsiveness; cognitive skill necessary for feeding, toileting and grooming; overall dependence, considering physical and cognitive ability; and employability. Scores are determined by observation (by patient or caregiver) and fall into categories of disability, ranging from 0 (no disability), 1–11 (having mild to moderate disability), 12–29 (severe disability to vegetative state) to 30 (death). Inter-rater reliability ranged from 97%–98%, while test-retest reliability ranged from 92%–93%, and kappas ranged from 0.47 to 0.81 in a retrospective study. Validity has been established by comparing the scale to evoked potentials (r=0.35–0.78), length of stay (r=0.50), and GOS (r=0.62–0.80).27 Length of stay was measured by days in the hospital, and acute in-hospital death was a dichotomous variable (lived, died).

Neurochemical data collection

Lactate and pyruvate were measured daily for the first 5 days after injury using 1449 fresh, immediately frozen CSF samples (3 mL) that were collected as part of the BTRC research protocol from the tubing of the ventriculostomy located in the lateral ventricles of the brain that was placed as standard of care. All daily measures available for a subject (ranged from one–five measures per day) were averaged for analysis. Lactate and pyruvate measurements were conducted using HPLC with UV detection (model 486, Waters Corporation, Milford, MA) at 214 nm. Separation was achieved using a programmable autosampler (model 717, Waters Corporation) to inject the sample onto a polymeric guard column in line with an organic acids column at a constant temperature of 35°C. The carryover from the previous injection was <0.1% and cross-contamination was <0.1%. The mobile phase consists of 0.01 N sulfuric acid pH 2.1 at 0.8 mL/min flow rate. Peak areas are identified and integrated using microcomputer-based control Millenium software (Water Corporation) with samples calibrated from standard curves. Biomarker concentration of lactate, pyruvate, and ratio of lactate to pyruvate were log transformed to reduce variability and achieve normality for statistical analysis.

Analyses

Initial analysis focused on the first stage of genotype data available, which were the SNP genotypes from the MitoChip data, for potential association with acute death, length of stay in the hospital, GOS, NRS, and DRS at 3, 6, and 12 months, mortality, and neurochemical levels using either the chi-square test or the Fisher exact test. There were 19 SNPs from the MitoChip data that were informative and passed data quality checks for the first stage of analysis. The second stage of analysis focused on the SNPs that were significantly associated with at least one phenotype of interest in the first stage of analysis, which were T195C, A4917G, T4216C and A10398G.

Demographic summary statistics across these four different SNPs, including mean and standard error for continuous variables and frequency distribution for categorical variables, are reported in Table 2. Mean differences with continuous variables were calculated using the Student t-test. Group comparisons using categorical data were evaluated using either the chi-square test or the Fisher exact test. Univariate analysis between each SNP and outcome measures GOS, NRS, and DRS at 3, 6 and 12 months were explored initially by using Student t-test or Chi-square test as appropriate. Then Multivariate regression models were constructed to evaluate the effect of SNPs on outcomes controlling for important covariates. Clinically relevant covariates (e.g., age, GCS, sex) were also included in the multivariate models, regardless of univariate results. Given that NRS and DRS were measured at 3, 6, and 12 months, repeated measure linear mixed models were used to evaluate the association of NRS and DRS with SNPs over time. The beta coefficient, standard error, and p value for independent variables were reported for DRS in Table 3 (nonsignificant findings for NRS not shown). Since GOS was dichotomized into favorable (GOS 3, 4, 5) versus unfavorable (GOS 1, 2) and measured over time, longitudinal random effects logistic regression models were used to evaluate the association between dichotomized GOS (favorable vs. unfavorable) and SNPs over time. The odds ratios (ORs), 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and p-value for independent variables were computed and reported in Table 4. In each multivariate model, the interaction between SNP, time, sex, and GCS were explored and significant interactions were reported. These approaches allowed subjects to contribute different numbers of observations, thus fully using all of the available data. We used SAS version 9.3 PROC MIXED and PROC GLIMMIX procedures to estimate the repeated measure mixed models and longitudinal random effect logistic regression models, respectively.

Table 2.

Demographics by SNP

| Variable | T195C C vs. T | P value | T4216C C vs. T | P value | A4917G A vs. G | P value | A10398G A vs. G | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Sex | ||||||||

| Female |

44 (78.6%) 12 (21.4%) |

0.23 |

15 (24.6%) 46 (75.4%) |

0.86 |

55 (90.2%) 6 (9.8%) |

0.66 |

42 (76.4%) 13 (23.6%) |

0.23 |

| Male |

184 (85.2%) 32(14.8%) |

|

53 (23.0%) 177 (76%) |

|

203 (87.5%) 29 (12.5%) |

|

168 (84.0%) 32 (16.0%) |

|

|

GCS | ||||||||

| 3–4 |

60 (87%) 9 (13%) |

0.57 |

22 (29.3%) 53 (70.7%) |

0.15 |

64 (85.3%) 11 (14.7%) |

0.40 |

52 (83.9%) 10 (16.1%) |

0.85 |

| 5–8 |

167 (83%) 34 (17%) |

|

45 (21.0%) 167 (79.0%) |

|

193 (89.3%) 23 (10.7%) |

|

156 (81.7%) 35 (18.3%) |

|

|

Inj Mech | ||||||||

| Motor- vehicle |

111 (84.0%) 21 (16.0%) |

0.34 |

39 (27.7%) 102 (72.3%) |

0.07 |

122 (85.9%) 20 (14.1%) |

0.90 |

102 (82.9%) 21 (17.1%) |

0.82 |

| Fall |

25 (75.8%) 8 (24.2%) |

|

7 (19.4%) 29 (80.6%) |

|

32 (88.9%) 4 (11.1%) |

|

24 (80.0%) 6 (20.0%) |

|

| Motor- cycle |

24 (80.0%) 6 (20.0%) |

|

3 (9.7%) 28 (90.3%) |

|

29 (90.6%) 3 (9.4%) |

|

23 (82.1%) 5 (17.9%) |

|

| Other |

25 (92.6%) 2 (7.4%) |

|

11 (35.5%) 20 (64.5%) |

|

28 (90.3%) 3 (9.7%) |

|

19 (76.0%) 6 (24.0%) |

|

|

Age |

34.8±1.00 35.4±2.48 |

0.81 |

34.3±1.87 35.4±1.01 |

0.61 |

35.2±0.93 34.9±2.75 |

0.92 |

36.1±1.08 36.6±2.09 |

0.83 |

| Length of stay (days) | 20.6±0.88 20.6±1.30 | 0.99 | 19.7±1.46 20.7±0.86 | 0.56 | 20.3±0.79 21.3±2.06 | 0.63 | 20.0±0.85 20.9±2.14 | 0.66 |

P values based on chi-square analysis, with Fisher's Exact Test as appropriate and independent t-test.

GCS, Glasgow Coma Score; Inj Mech, Injury mechanism.

Table 3.

Multivariable Model between DRS and A10398G

| A10398G | Coefficient | Standard error | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age |

0.2726 |

0.05 |

<0.0001 |

| Sex | |||

| Female Male (reference) |

1.68 |

1.71 |

0.33 |

| GCS | |||

| 3–4 5–8 (reference) |

9.68 |

1.68 |

<0.0001 |

| Time*A10398G | 0.0013 | ||

GCS, Glasgow Coma Score.

Table 4.

Multivariable Model between Favorable GOS (3,4,5 vs. 1,2) and T195C

| T195C | Odds ratio | Confidence interval | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age |

0.941 |

0.916–0.966 |

<0.0001 |

| GCS | |||

| 3–4 |

0.095 |

0.041–0.218 |

<0.0001 |

| 5–8 (reference) |

|

|

|

| Time | |||

| 3 months |

0.924 |

0.478–1.786 |

0.81 |

| 6 months |

1.217 |

0.654–2.265 |

0.53 |

| 12 months(reference) |

|

|

|

| T195C*Sex |

0.03 |

||

| T195C C vs. T in Female |

3.608 |

0.535–24.33 |

0.19 |

| T195C C vs. T in Male | 0.269 | 0.068–1.065 | 0.06 |

GCS, Glasgow Coma Score.

In an attempt to control for population substructure, analyses were conducted in self-reported Whites only. This was particularly important given how disparate allele frequencies are for mitochondrial polymorphisms when comparing individuals from different ancestries (for example, the A allele frequency for A10398G is ∼ 76% in Americans from European ancestry, but is only seen in ∼2% of Americans from African decent28) and given that the number of individuals from non-European ancestry enrolled in our study was not high enough to allow for independent analyses.

Results

SNPs and outcomes

Nineteen mitochondrial SNPs were variable enough in this population to warrant analyses during the first stage of investigation (A10398G, A10550G, A11947G, A12308G, A14233G, A16519G, A4917G, A8701G, C12705T, C14766T, C3494T, C7028T, G13708A, T10873C, T13789C, T146C, T195C, T4216C, and T477C). Four of these 19 SNPs (A10398G, A4917G, T195C, and T4216C) indicated associations (p≤0.05) and were genotyped for the second stage in the larger (n=336) cohort and each passed quality control measures. While genotype data was available for all 336 subjects, lack of outcome data for some subjects at all time points were not available; so for final analyses the number of subjects analyzed fluctuated depending upon the phenotype being evaluated. The demographics of the TBI subjects investigated were primarily male, young, and with most injuries related to motor vehicle accidents. Please see Table 2 that separately presents demographic and clinical characteristics of the subjects that entered into analyses for each SNP.

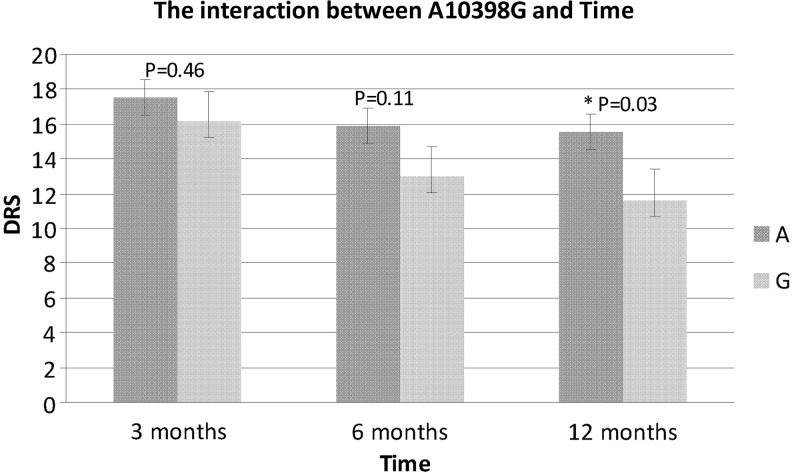

A10398G was associated with Disability Rating Scale (DRS) at 6 and 12 months (p=0.02; Table 5) in the univariate analyses and this association was upheld in the multivariate model between DRS and A10398G where a time by SNP interaction was significant (p=0.001; Table 4). The A10398 allele was associated with slower recover over time (Fig. 1).

Table 5.

Univariate Analysis between SNPs and Outcomes

| Variable | A4917G A vs. G | P value | T195C C vs. T | P value | T4216C C vs. T | P value | A10398G A vs. G | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

GOS at 3 months | ||||||||

| Unfavorable |

56 (83.6%) 11 (16.4%) |

|

49 (83.0%) 10 (17.0%) |

|

19 (28.8%) 47 (71.2%) |

|

48 (85.7%) 8 (14.3%) |

|

| Favorable |

125 (91.2%) 12 (8.8%) |

0.16 |

109 (84.9%) 21 (16.1%) |

1.00 |

31 (22.6%) 106 (77.4%) |

0.38 |

92 (76.7%) 28 (23.3%) |

0.23 |

|

GOS at 6 months | ||||||||

| Unfavorable |

66 (85.7%) 11 (14.3%) |

|

63 (91.3%) 6 (8.7%) |

|

21 (27.6%) 55 (72.4%) |

|

56 (84.8%) 10 (15.2%) |

|

| Favorable |

143 (87.2) 21 (12.8%) |

0.84 |

125 (81.2%) 29 (18.8%) |

0.07 |

41 (25.0%) 123 (75.0%) |

0.75 |

111 (78.7%) 30 (21.3%) |

0.35 |

|

GOS at 12 months | ||||||||

| Unfavorable |

62 (84.9%) 11 (15.1%) |

|

59 (88.1%) 8 (11.9%) |

|

20 (27.8%) 52 (72.2%) |

|

51 (85.0%) 9 (15.0%) |

|

| Favorable |

113 (88.3%) 15 (11.7%) |

0.52 |

98 (81.7%) 22 (18.3%) |

0.30 |

32 (25.2%) 95 (74.8%) |

0.74 |

83 (77.6%) 24 (22.4%) |

0.31 |

|

DRS at 3 months | ||||||||

| |

14.4±0.82 16.5±2.47 |

0.38 |

14.3±0.88 13.8±1.95 |

0.82 |

14.8±1.58 14.4±0.89 |

0.85 |

15.0±0.95 12.6±1.66 |

0.23 |

|

DRS at 6 months | ||||||||

| |

12.9±0.94 15.9±2.51 |

0.27 |

13.2±1.02 12.0±2.08 |

0.64 |

13.4±1.68 13.1±1.04 |

0.89 |

14.5±1.13 9.18±1.63 |

0.02 |

|

DRS at 12 months | ||||||||

| |

13.4±1.10 16.4±3.24 |

0.37 |

13.4±1.22 13.8±2.47 |

0.90 |

13.5±2.06 13.8±1.22 |

0.88 |

15.4±1.34 9.0±2.02 |

0.02 |

| NRS at 3 months | ||||||||

| |

46.3±1.85 48.9±6.54 |

0.67 |

45.8±1.91 48.8±5.00 |

0.51 |

47.5±3.31 46.2±2.11 |

0.74 |

47.9±2.22 44.8±4.00 |

0.49 |

|

NRS at 6 months | ||||||||

| |

46.1±1.80 46.5±6.99 |

0.94 |

45.6±1.87 48.3±4.89 |

0.54 |

45.9±2.94 46.2±2.15 |

0.95 |

46.1±2.45 46.8±3.21 |

0.86 |

|

NRS at 12 months | ||||||||

| |

48.6±2.26 46.3±8.20 |

0.76 |

46.6±2.25 52.5±6.81 |

0.32 |

48.9±3.91 48.4±2.66 |

0.92 |

47.6±3.10 52.9±4.31 |

0.33 |

|

Acute death | ||||||||

| Yes |

166 (88.8%) 21 (11.2%) |

|

143 (82.7) 30(173.%) |

|

43 (23.1%) 143(76.9%) |

|

130 (80.3%) 32 (19.8%) |

|

| No |

64 (84.2%) 12 (15.8%) (72.0%) 0.43 |

0.31 |

60 (85.7%) 10 (14.3%) |

0.71 |

21 (28.0%) 54 |

0.43 |

55 (85.9%) 9 (14.1%) |

0.35 |

|

LOS | ||||||||

| 20.2±0.79 21.3±2.06 | NS | 20.6±0.88 20.5±81.30 | NS | 19.7±1.46 20.7±0.86 | NS | 20.0±0.85 20.9±2.14 | NS | |

DRS, Disability Rating Scale; GOS, Glasgow Outcome Scale; NRS, LOS, Length of Stay; Neurobehavioral Rating Scale.

GOS unfavorable=1 or 2, GOS favorable=3, 4, or 5. For DRS, a higher score suggests poorer function. For NRS, a high score reflects higher function.

FIG. 1.

The interaction between time and A10398G.

T195C and interaction with sex was associated with Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS) (p=0.03; Table 5). The T allele appears to be associated with poorer outcomes in females, with the C allele associated with poorer outcomes in males.

SNPs and cerebrospinal fluid lactate:pyruvate level

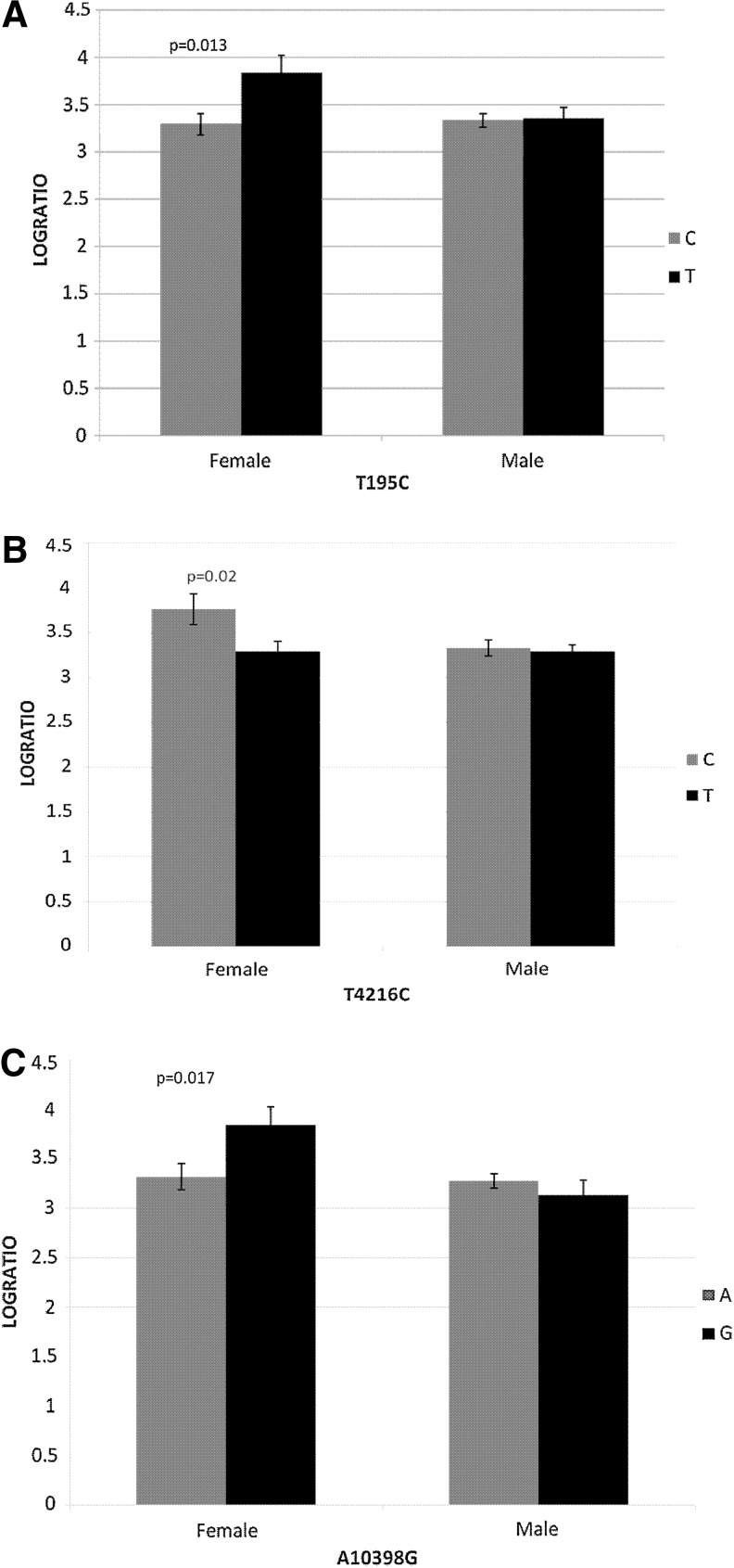

The ratio of lactate to pyruvate from cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) was significantly higher, indicative of mitochondrial dysfunction, for the T allele of T195C (p=0.01); the C allele of T4216C (p=0.02); and the G allele of A10398G (p=0.01), but only for females (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Impact of mtDNA polymorphisms (A) T195C; (B) T4216C; and (C) A10398G on cerebrospinal fluid lactate to pyruvate ratio by sex over the first 5 days after severe TBI.

Discussion

This study contributes to the growing body of literature supporting a role for the mitochondria in patient outcomes after TBI. This study links variation in the mitochondrial genome to patient outcomes up to 1 year after TBI that may be driven by mitochondrial functional differences. Although exploratory in nature, the role of mitochondrial variation in recovery after TBI may be especially relevant to recovery of female patients.

A10398G appears to impact functional outcome attained after severe TBI with the A10398 allele associated with slower recovery over time. This is consistent with findings that the A10398 allele is associated with susceptibility to neurodegenerative disorders, mental health disorders, and cancer.28–30 The A10398G mitochondrial polymorphism is located within the NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase subunit ND3 gene (ND3) that functions within complex I of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS). This polymorphism results in a threonine to alanine amino acid substitution (T114A) that appears to impact function of this subunit, which is located in a hydrophobic portion of complex I.31 The A10398G SNP has functional consequences with the A10398 allele implicated in lower mitochondrial matrix pH and increased intracellular calcium dynamics.32

CSF lactate to pyruvate ratio was significantly associated with polymorphisms in the mitochondria, but only in females. The ratio of lactate to pyruvate from CSF was significantly higher, indicative of mitochondrial dysfunction, for the T allele of T195C, the C allele of T4216C, and the G allele of A10398G in females. Function of the A10398G polymorphism was discussed above. The T4216C mitochondrial polymorphism is located within the NADH dehydrogenase 1 gene (ND1) that functions within complex I of mitochondrial OXPHOS. This polymorphism results in a thymine to cytosine amino acid substitution that has been associated with reduced complex 1 efficiency, resulting in impaired ATP production.33 Interestingly, the same allele associated with mitochondrial dysfunction in our study, 4612C, has been associated with susceptibility to sepsis after traumatic injury in two studies.34,35 The T195C polymorphism is located within the noncoding hypervariable region of the mitochondrial genome. While much less is known about its potential functional consequences, T195C is within a region of the mitochondrial genome that is believed to be involved with mitochondrial DNA replication36 and organization of mitochondrial genomes within a cell.37

Our exploratory sex-based findings related to mitochondrial function and impact on association between mitochondrial SNPs and outcomes post-TBI were unexpected. Animal and in vitro studies have shown that estrogen has a regulatory effect on mitochondrial gene expression38–42 through the OXPHOS pathway.43–50 Sex-based mitochondrial SNP associations have also been noted for Parkinson disease. For example, the 10398G allele was found to have a protective effect with protection being stronger in females in one study,29 while another found haplogroup J to be protective, but only in males.51 Yet another found the 4216C allele to be weakly associated with susceptibility but only in males.52 Literature continues to build regarding sex-based associations for mitochondrial SNPs in neurodegenerative conditions; however no study to date has addressed these issues following severe TBI in the human. Additionally, the impact of sex differences on patient outcomes after TBI in general is unclear and requires more attention in research studies. Data from 72,294 patients with moderate to severe TBI in the National Trauma Database indicated that being female was associated with better outcomes;53 however other large studies,54 metaanalysis,55 and systematic review studies56,57 have found that women either had worse outcomes or were no different from their matched male counterparts.

This study is the first to associate mitochondrial SNPs with functional outcome attained after severe TBI, as well as mitochondrial function in the acute period following severe TBI in humans. Additionally, our study indicates that sex of the TBI patient may impact outcomes attained, potentially through mitochondrial mechanisms.

We acknowledge that one limitation of our study is the relatively small sample size for a genetic association study; however the study does have strengths that offset this limitation. The sample size used for this novel study is respectable for one that addresses patient outcomes up to 1 year after TBI. The study does have findings that hold up to conservative Bonferroni correction for multiple testing of the four SNPs; our findings are consistent with the literature linking mitochondrial variation with other disorders; and we present functional data to support our findings. Additional investigations in larger cohorts are necessary.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant numbers R01NR008424; P50NS30318; and R01NR013342).

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.NINDS (2009). Traumatic Brain Injury: Hope Through Research. http://www.ninds.nih.gov/disorders/tbi/tbi.htm (last accessed June4, 2013)

- 2.Faul M, Xu L, Wald MM, and Coronado VG. (2010). Traumatic Brain Injury in the United States: Emergency Department Visits, Hospitalizations, and Deaths. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta (GA) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sendroy-Terrill M, Whiteneck GG, and Brooks CA. (2010). Aging with traumatic brain injury: Cross-sectional follow-up of people receiving inpatient rehabilitation over more than 3 decades. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 91, 489–497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoofien D, Gilboa A, Vakil E, and Donovick PJ. (2001). Traumatic brain injury (TBI) 10–20 years later: A comprehensive outcome study of psychiatric symptomatology, cognitive abilities and psychosocial functioning. Brain Inj 15, 189–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jennekens N, de Casterle BD, and Dobbels F. (2010). A systematic review of care needs of people with traumatic brain injury (TBI) on a cognitive, emotional and behavioural level. J Clin Nurs 19, 1198–1206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dikmen S, Machamer J, Fann JR, and Temkin NR. (2010). Rates of symptom reporting following traumatic brain injury. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 16, 401–411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schonberger M, Ponsford J, Olver J, Ponsford M, and Wirtz M. (2011). Prediction of functional and employment outcome 1 year after traumatic brain injury: A structural equation modelling approach. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 82, 936–941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holt I. (1994). The structure and expression of normal and mutant mitochondrial genomes. In: Mitochondria: DNA, Proteins and Disease. Portland Press: London, pps. 27–54 [Google Scholar]

- 9.MITOMAP (2013). MITOMAP: A Human Mitochondrial Genome Database. http://www.mitomap.org (last accessed June4, 2013)

- 10.Sullivan PG, Keller JN, Mattson MP, and Scheff SW. (1998). Traumatic brain injury alters synaptic homeostasis: Implications for impaired mitochondrial and transport function. J Neurotrauma 15, 789–798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vink R, Golding EM. and Headrick JP. (1994). Bioenergetic analysis of oxidative metabolism following traumatic brain injury in rats. J Neurotrauma 11, 265–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Verweij BH, Muizelaar JP, Vinas FC, Peterson PL, Xiong Y, and Lee CP. (2000). Impaired cerebral mitochondrial function after traumatic brain injury in humans. J Neurosurg 93, 815–820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Signoretti S, Marmarou A, Tavazzi B, Lazzarino G, Beaumont A. and Vagnozzi R. (2001). N-Acetylaspartate reduction as a measure of injury severity and mitochondrial dysfunction following diffuse traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma 18, 977–991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lifshitz J, Friberg H, Neumar RW, et al. (2003). Structural and functional damage sustained by mitochondria after traumatic brain injury in the rat: Evidence for differentially sensitive populations in the cortex and hippocampus. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 23, 219–231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vagnozzi R, Marmarou A, Tavazzi B, et al. (1999). Changes of cerebral energy metabolism and lipid peroxidation in rats leading to mitochondrial dysfunction after diffuse brain injury. J Neurotrauma 16, 903–913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kawamata T, Katayama Y, Hovda DA, Yoshino A, and Becker DP. (1995). Lactate accumulation following concussive brain injury: The role of ionic fluxes induced by excitatory amino acids. Brain Res 674, 196–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singh IN, Sullivan PG, Deng Y, Mbye LH, and Hall ED. (2006). Time course of post-traumatic mitochondrial oxidative damage and dysfunction in a mouse model of focal traumatic brain injury: Implications for neuroprotective therapy. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 26, 1407–1418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hatton J, Rosbolt B, Empey P, Kryscio R, and Young B. (2008). Dosing and safety of cyclosporine in patients with severe brain injury. J Neurosurg 109, 699–707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cook AM, Whitlow J, Hatton J, and Young B. (2009). Cyclosporine A for neuroprotection: Establishing dosing guidelines for safe and effective use. Expert Opin Drug Saf 8, 411–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lulic D, Burns J, Bae EC, van Loveren H, and Borlongan CV. (2011). A review of laboratory and clinical data supporting the safety and efficacy of cyclosporin A in traumatic brain injury. Neurosurgery 68, 1172–1185; discussion 1185–1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miller SA, Dykes DD, and Polesky HF. (1988). A simple salting out procedure for extracting DNA from human nucleated cells. Nucleic Acids Res 16, 1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maitra A, Cohen Y, Gillespie SE, et al. (2004). The Human MitoChip: A high-throughput sequencing microarray for mitochondrial mutation detection. Genome Res 14, 812–819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilson JT, Pettigrew LE, and Teasdale GM. (1998). Structured interviews for the Glasgow Outcome Scale and the extended Glasgow Outcome Scale: Guidelines for their use. J Neurotrauma 15, 573–585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pettigrew LE, Wilson JT, and Teasdale GM. (2003). Reliability of ratings on the Glasgow Outcome Scales from in-person and telephone structured interviews. J Head Trauma Rehabil 18, 252–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilson JT, Pettigrew LE, and Teasdale GM. (2000). Emotional and cognitive consequences of head injury in relation to the glasgow outcome scale. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 69, 204–209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vanier M, Mazaux JM, Lambert J, Dassa C, and Levin HS. (2000). Assessment of neuropsychologic impairments after head injury: Interrater reliability and factorial and criterion validity of the Neurobehavioral Rating Scale-Revised. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 81, 796–806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ditunno JF, Jr., (1992). Functional assessment measures in CNS trauma. J Neurotrauma 9Suppl 1, S301–305 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Canter JA, Kallianpur AR, Parl FF, and Millikan RC. (2005). Mitochondrial DNA G10398A polymorphism and invasive breast cancer in African-American women. Cancer Res 65, 8028–8033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van der Walt JM, Nicodemus KK, Martin ER, et al. (2003). Mitochondrial polymorphisms significantly reduce the risk of Parkinson disease. Am J Hum Genet 72, 804–811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kato T, Kunugi H, Nanko S, and Kato N. (2001). Mitochondrial DNA polymorphisms in bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord 62, 151–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ragan CI. (1987). Structure of NADH-Ubiquinone reductase (complex-I). Curr Top Bioenerg 15, 1–36 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kazuno AA, Munakata K, Nagai T, et al. (2006). Identification of mitochondrial DNA polymorphisms that alter mitochondrial matrix pH and intracellular calcium dynamics. PLoS Genet 2, e128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ross OA, McCormack R, Maxwell LD, et al. (2003). mt4216C variant in linkage with the mtDNA TJ cluster may confer a susceptibility to mitochondrial dysfunction resulting in an increased risk of Parkinson's disease in the Irish. Exp Gerontol 38, 397–405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huebinger RM, Gomez R, McGee D, et al. (2010). Association of mitochondrial allele 4216C with increased risk for sepsis-related organ dysfunction and shock after burn injury. Shock 33, 19–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gomez R, O'Keeffe T, Chang LY, Huebinger RM, Minei JP, and Barber RC. (2009). Association of mitochondrial allele 4216C with increased risk for complicated sepsis and death after traumatic injury. J Trauma 66, 850–857; discussion 857–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chang DD, and Clayton DA. (1985). Priming of human mitochondrial DNA replication occurs at the light-strand promoter. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 82, 351–355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.He J, Mao CC, Reyes A, et al. (2007). The AAA+ protein ATAD3 has displacement loop binding properties and is involved in mitochondrial nucleoid organization. J Cell Biol 176, 141–146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nilsen J, Irwin RW, Gallaher TK, and Brinton RD. (2007). Estradiol in vivo regulation of brain mitochondrial proteome. J Neurosci 27, 14069–14077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Van Itallie CM, and Dannies PS. (1988). Estrogen induces accumulation of the mitochondrial ribonucleic acid for subunit II of cytochrome oxidase in pituitary tumor cells. Mol Endocrinol 2, 332–337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bettini E, and Maggi A. (1992). Estrogen induction of cytochrome c oxidase subunit III in rat hippocampus. J Neurochem 58, 1923–1929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen J, Delannoy M, Odwin S, et al. (2003). Enhanced mitochondrial gene transcript, ATP, bcl-2 protein levels, and altered glutathione distribution in ethinyl estradiol-treated cultured female rat hepatocytes. Toxicol Sci 75, 271–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen J, Gokhale M, Li Y, Trush MA, and Yager JD. (1998). Enhanced levels of several mitochondrial mRNA transcripts and mitochondrial superoxide production during ethinyl estradiol-induced hepatocarcinogenesis and after estrogen treatment of HepG2 cells. Carcinogenesis 19, 2187–2193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lemasters JJ, Qian T, Bradham CA, et al. (1999). Mitochondrial dysfunction in the pathogenesis of necrotic and apoptotic cell death. J Bioenerg Biomembr 31, 305–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zheng J, and Ramirez VD. (1999). Purification and identification of an estrogen binding protein from rat brain: Oligomycin sensitivity-conferring protein (OSCP), a subunit of mitochondrial F0F1-ATP synthase/ATPase. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 68, 65–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zheng J, and Ramirez VD. (1999). Rapid inhibition of rat brain mitochondrial proton F0F1-ATPase activity by estrogens: Comparison with Na+, K+ -ATPase of porcine cortex. Eur J Pharmacol 368, 95–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nilsen J, and Brinton RD. (2004). Mitochondria as therapeutic targets of estrogen action in the central nervous system. Curr Drug Targets CNS Neurol Disord 3, 297–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mattson MP, Robinson N, and Guo Q. (1997). Estrogens stabilize mitochondrial function and protect neural cells against the pro-apoptotic action of mutant presenilin-1. Neuroreport 8, 3817–3821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Arnold S, de Araujo GW, and Beyer C. (2008). Gender-specific regulation of mitochondrial fusion and fission gene transcription and viability of cortical astrocytes by steroid hormones. J Mol Endocrinol 41, 289–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Giordano C, Montopoli M, Perli E, et al. (2011). Oestrogens ameliorate mitochondrial dysfunction in Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy. Brain 134, 220–234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Araujo GW, Beyer C, and Arnold S. (2008). Oestrogen influences on mitochondrial gene expression and respiratory chain activity in cortical and mesencephalic astrocytes. J Neuroendocrinol 20, 930–941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gaweda-Walerych K, Maruszak A, Safranow K, et al. (2008). Mitochondrial DNA haplogroups and subhaplogroups are associated with Parkinson's disease risk in a Polish PD cohort. J Neural Transm 115, 1521–1526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kirchner SC, Hallagan SE, Farin FM, et al. (2000). Mitochondrial ND1 sequence analysis and association of the T4216C mutation with Parkinson's disease. Neurotoxicology 21, 441–445 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Berry C, Ley EJ, Tillou A, Cryer G, Margulies DR, and Salim A. (2009). The effect of gender on patients with moderate to severe head injuries. J Trauma 67, 950–953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ottochian M, Salim A, Berry C, Chan LS, Wilson MT, and Margulies DR. (2009). Severe traumatic brain injury: Is there a gender difference in mortality? Am J Surg 197, 155–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Farace E, and Alves WM. (2000). Do women fare worse? A metaanalysis of gender differences in outcome after traumatic brain injury. Neurosurg Focus 8, e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Husson EC, Ribbers GM, Willemse-van Son AH, Verhagen AP, and Stam HJ. (2010). Prognosis of six-month functioning after moderate to severe traumatic brain injury: A systematic review of prospective cohort studies. J Rehabil Med 42, 425–436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Slewa-Younan S, van den Berg S, Baguley IJ, Nott M, and Cameron ID. (2008). Towards an understanding of sex differences in functional outcome following moderate to severe traumatic brain injury: A systematic review. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 79, 1197–1201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]