Abstract

Sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) is involved in hyper-proliferative diseases such as cancer and pulmonary arterial hypertension. We have synthesized inhibitors that are selective for the two isoforms of sphingosine kinase (SK1 and SK2) that catalyze the synthesis of S1P. A thiourea adduct of sphinganine (F02) is selective for SK2 whereas the 1-deoxysphinganines 55-21 and 77-7 are selective for SK1. (2S,3R)-1-Deoxysphinganine (55-21) induced the proteasomal degradation of SK1 in human pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells and inhibited DNA synthesis, while the more potent SK1 inhibitors PF-543 and VPC96091 failed to inhibit DNA synthesis. These findings indicate that moderate potency inhibitors such as 55-21 are likely to have utility in unraveling the functions of SK1 in inflammatory and hyperproliferative disorders.

Introduction

Sphingosine kinase (SK), which catalyzes the conversion of sphingosine (Sph) to sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P), exists as two isoforms, SK1 and SK2. The isoforms are encoded by distinct genes and differ in their biochemical properties, subcellular localization, and function.1 There is accumulating evidence that SK1 is involved in hyperproliferative diseases; for instance, SK1 mRNA transcript and/or protein expression are increased in various human tumors.2 Moreover, siRNA knockdown of SK1 reduces proliferation of glioblastoma cells3 and androgen-independent PC-3 prostate cancer cells.4 Sustained hypoxia increases SK1 expression in proliferating human pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells (PASMC), which might contribute to their increased survival5 and vascular remodeling in pulmonary arterial hypertension. There is also evidence that SK2 may play an important role in cancer. For example, siRNA knockdown of SK2 enhances doxorubicin-induced apoptosis of breast or colon cancer cells6 and reduces cancer cell proliferation and migration/invasion.7

As SK1 and SK2 are potential and promising targets for cancer chemoprevention, a number of SK inhibitors have been prepared in order to reduce cancer cell survival but only very few have been found to be isoform selective. For example, (2R,3S,4E)-N-methyl-5-(4′-pentylphenyl)-2-amino-4-pentene-1,3-diol (commonly referred to as SK1-I and BML-258) is a selective SK1 inhibitor that enhances the survival of mice in an orthotopic intracranial tumor model.8 An analogue of the oral multiple sclerosis drug FTY720 (Gilenya™), (2R)-2-amino-2-(methoxymethyl)-4-(4′-n-octylphenyl)butan-1-ol ((R)-FTY720-OMe, ROME), is a selective, enantioselective, competitive (with Sph) inhibitor of SK2.9 Treatment of MCF-7 breast cancer cells with ROME abrogates the enrichment of actin into lamellipodia in response to S1P.9 Another SK2-selective inhibitor is the nonlipid molecule 4-pyridinemethyl 3-(4′-chlorophenyl)-adamantane-1-carboxamide (ABC294640), which is also a competitive (with Sph) inhibitor of SK2 activity. ABC294640 reduces formation of intracellular S1P in cancer cells and prevents tumor progression in mice with mammary adenocarcinoma xenografts.10 The Ki values for inhibition of SK2 by (R)-FTY720-OMe and ABC294640 are very similar (16.5 μM vs 10 μM, respectively).9,10 Recently, 3-(2-amino-ethyl)-5-[3-(4-butoxyl-phenyl)-propylidene]-thiazolidine-2,4-dione (K145) was identified as a selective inhibitor of SK2.11 This compound reduced S1P levels, inhibited growth and suppressed ERK/AKT signaling in U937 cells and inhibited tumor growth in vivo.11

Diastereomers of diverse saturated sphingoid bases such as sphinganine,12 safingol (L-threo-sphinganine, the first putative SK1 inhibitor to enter a phase I trial),13 fumonisin B1,14 spisulosine ((2S,3R)-1-deoxysphinganine, ES-285),15 enigmols (1-deoxy-3,5-dihydroxysphinganines),16 and phytosphingosine (PHS)17 were found to disrupt the normal biosynthesis of various signaling sphingolipids and to possess pro-apoptotic properties via multiple mechanisms in numerous cell types. In previous work, we showed that N-phenethylisothiocyanate derivatives of sphingosine and sphinganine have a higher cytotoxic activity to HL-60 leukemic cells than sphinganine and safingol.18 These findings suggest that adducts of synthetic saturated sphingoid bases may be putative inhibitors of either or both SK isoforms. In this communication, we report the synthesis of a series of saturated D-erythro long-chain bases and an assessment of their ability to inhibit the two isoforms of SK. Our data have identified new isoform-selective SK inhibitors, of which 55-21 is also able to induce proteasomal degradation of SK1 and reduce DNA synthesis in human pulmonary smooth muscle cells (PASMC).

Results and discussion

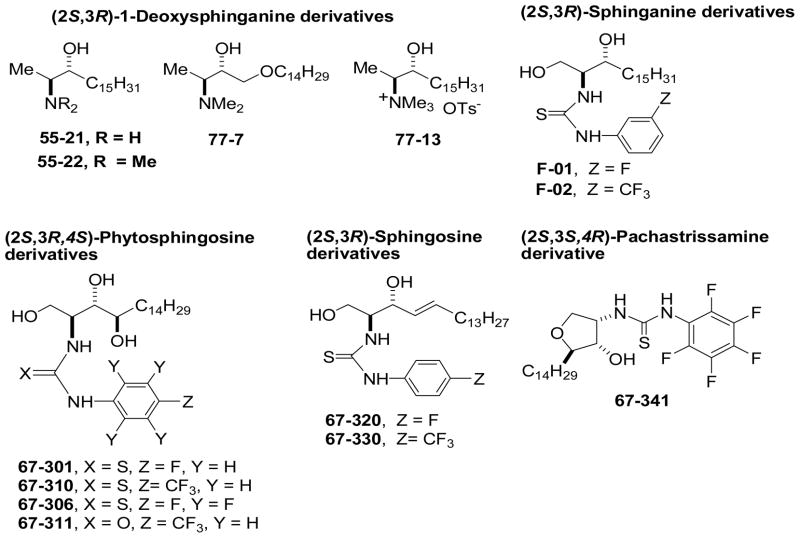

Fig. 1 shows the structures of the 1-deoxysphingoid bases 55-21, 55-22, 77-7, and 77-13; the thiourea-sphinganine bases F01 and F02; the 4-sphingenine (sphingosine) adducts 67-320 and 67-330; the thiourea adduct of 2-epi-pachastrissamine19 67-341; and the thiourea-PHS derivatives 67-301, 67-306, 67-310, and the urea-PHS derivative 67-311.

Fig. 1.

Structures of sphingoid bases evaluated as SK inhibitors.

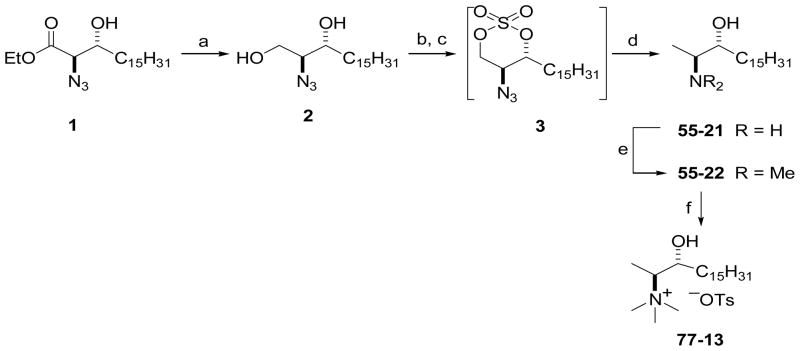

Scheme 1 outlines the preparation of 1-deoxysphinganine analogues 55-21 and 55-22 via cyclic sulfate intermediates of (2S,3R)-2-azidosphinganine. Azidoester 1 was prepared by asymmetric dihydroxylation of ethyl octadecenoate using AD-mix-β ((DHQD)2PHAL), followed by conversion to a cyclic sulfate intermediate and regioselective azidation with sodium azide in aqueous acetone as described previously.20 Reduction of ester 1 with NaBH4 gave 2-azido-1,3-diol 2, which was converted to the 2-azido-1,3-cyclic sulfate intermediate 3 by reaction with SOCl2 in the presence of pyridine, followed by oxidation of resulting cyclic sulfite with catalytic RuO4. Without further purification, 3 was subjected to reduction with sodium borohydride in DMF in the presence of sodium iodide, which removed the primary hydroxyl group and reduced the azide, affording (2S,3R)-2-amino-3-octadecanol (55-21) in 79% yield. The reaction of 55-21 with formaldehyde in the presence of NaBH3CN in MeOH furnished the N,N-dimethylamino derivative 55-22 in 82% yield. N-Methylation of 55-22 with methyl tosylate in THF gave the N,N,N-trimethylammonium tosylate salt, 77-13.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of 1-deoxysphingoid derivatives 55-21, 55-22, and 77-13 via cyclic sulfate chemistry. Reagents and conditions: (a) NaBH4, THF, MeOH, −78 °C – rt; (b) SOCl2, py, CH2Cl2, −78 °C, 2 h, then rt, 2 h; (c) cat. RuCl3·3H2O, NaIO4, MeCN/H2O (5:1), rt, 2 h; (d) NaBH4 (2 equiv), NaI (1 equiv), DMF, 0 °C – rt, 48 h, then aq. HCl (79%); (e) CH2O (10 equiv), NaBH3CN (11 equiv), MeOH, 0 °C – rt, 48 h (82%); (f) p-TsOMe, THF, rt, overnight (100%).

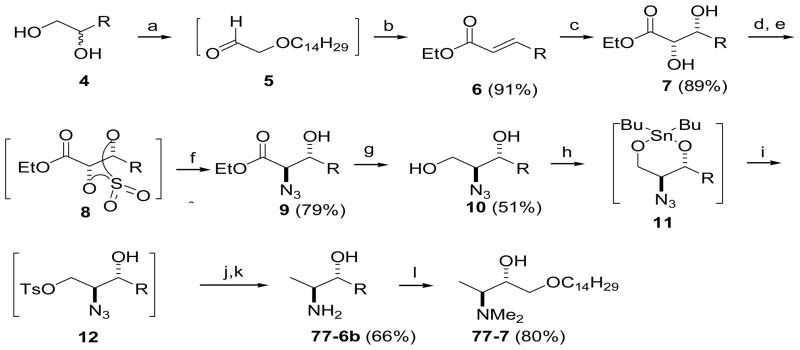

As shown in Scheme 2, the synthesis of oxyspisulosine analog 77-7, which contains an oxygen atom in the aliphatic chain, started with rac-1-O-tetradecylglycerol (4).21 Oxidative cleavage of vicinal diol 4 with NaIO4 afforded aldehyde 5. HWE reaction of 5 with (EtO)2P(O)CH2CO2Et in aqueous 2-propanol the presence of K2CO3 afforded (E)-α,β-unsaturated ester 6 with good E selectivity. Asymmetric dihydroxylation of ester 6 with AD-mix-β proceeded smoothly, providing chiral 2,3-diol ester 7 in 89% yield. Conversion of diol 7 to cyclic sulfate intermediate 8, followed by regioselective azidation gave azidoester 9, and reduction of the ester functionality in 9 with NaBH4 gave 2-azido1,3-diol 10. We next attempted to remove the primary hydroxyl group from 1,3-diol 10 by the cyclic sulfate methodology shown in Scheme 1. However, when the cyclic sulfate of 10 was reduced with NaBH4 we found that the oxygen atom in the aliphatic chain affected the regioselectivity of the reduction, resulting in a mixture of primary and secondary alcohols that was difficult to purify. Therefore, we devised a novel route involving a dibutylstannane intermediate (11) to synthesize 77-7 (Scheme 2). Reaction of 10 with dibutyltin oxide followed by tosylation of 11 gave intermediate 12, which was converted to 77-6b in two steps and 66% overall yield from 10. In contrast to the reduction of 3, the azido group was not completely reduced even in DMF at elevated temperature. Therefore, catalytic hydrogenolysis was necessary to complete the reduction of tosylate 12.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of 1-deoxysphingoid derivative 77-7 via dibutylstannane-mediated monotosylation of 1,3-diol 10. Reagents and conditions: (a) NaIO4, THF/H2O, 0 °C – rt, 2 h; (b) (EtO)2P(O)CH2CO2Et, K2CO3, 2-PrOH/H2O (1:1), 0 °C rt, overnight; (c) AD-mix β, MeSO2NH2, t-BuOH/H2O (1:1), rt; (d) SOCl2, py, CH2Cl2, 0 °C; (e) cat. RuCl3·3H2O, NaIO4, MeCN/H2O (5:2); (f) NaN3 (3 equiv), Me2CO/H2O (2:1), then Et2O, aq. H2SO4; (g) NaBH4, THF/MeOH (100:1), 0 °C – rt; (h) Bu2SnO, toluene, reflux; (i) p-TsCl, CH2Cl2, 0 °C – rt, overnight; (j) NaBH4, THF, 0 °C – rt; (k) Pd(OH)2/C, MeOH, rt; (l) CH2O, NaBH3CN (12.5 equiv), MeOH, 0 °C – rt, 48 h (80%).

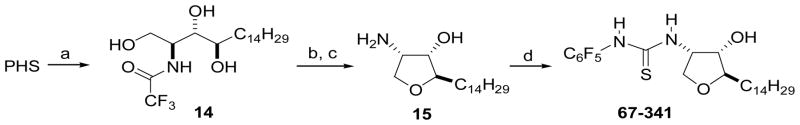

The N-arylthiourea and -arylurea derivatives were prepared by the addition of the amino group of Sph, sphinganine, or D-ribo-PHS to the electrophilic carbon of an aryl isothiocyanate or aryl cyanate in CHCl3/CH3OH (1:1) (ESI†). 67-341 was prepared from 2-epi-pachastrissamine (15)19 and pentafluorophenyl isothiocyanate. Cyclic amine 15 was obtained by regioselective tosylation of trifluoroacetamido-D-ribo-PHS 14 followed by hydrolysis of the N-protecting group with NaOH in MeOH (Scheme 3). Thiourea derivatives F-01 and F-02 were prepared by the reaction of sphinganine with an aryl isothiocyanate (ESI).

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of 67-341, a thiourea derivative of 2-epi-pachastrissamine. Reaction conditions: (a) CF3CO2Et, MeOH, rt, overnight (95%); (b) p-TsCl (1.1 equiv), py/CH2Cl2 (1:1), 0 °C – rt (80%); (c) NaOH, MeOH, reflux, 3 h (100%); (d) C6F5NCS.

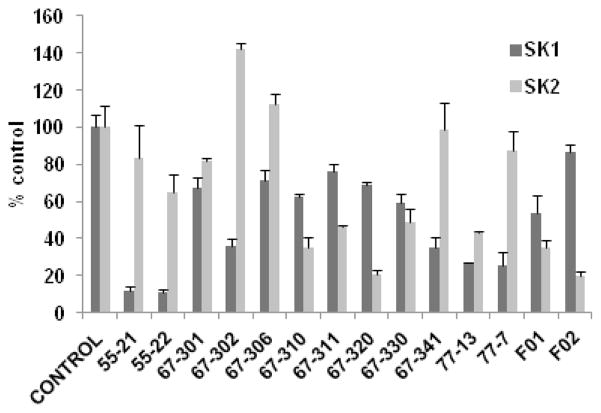

We assessed the effects of fluorine and trifluoromethyl substitution in the benzene ring of the putative inhibitors (Fig. 2). The N-(4-fluorophenyl)thiourea-PHS derivative 67-301 is a weak and nonselective SK inhibitor, but effectiveness for SK1 versus SK2 is improved by insertion of five fluorine atoms into the benzene ring to afford 67-306, albeit the inhibition remains moderate. Thiourea 67-310 and urea 67-311, which are both p-trifluoromethylphenyl PHS derivatives, are moderately effective SK2 inhibitors (64.5 ± 4.9% and 53.9 ± 0.9% inhibition at 50 μM, respectively). Notably, the N-(4-fluorophenyl)thiourea-Sph derivative 67-320 is a more effective SK2 inhibitor (79.2 ± 1.9% inhibition at 50 μM) whereas its p-trifluoromethylphenyl analogue 67-330 is a weak inhibitor of both SK isoforms. The cyclic N-(pentafluorophenyl)thioureido derivative 67-341 is a more effective SK1 inhibitor (64.7 ± 5.3% inhibition at 50 μM). Sphinganine thiourea derivative F-02 is more effective for SK2 (80 ± 2% inhibition at 50 μM), but its analogue F-01 is less effective. 1-Deoxysphinganine analog 55-21 and its N,N-dimethyl derivative 55-22 are more effective SK1 inhibitors. Insertion of an oxygen atom into the aliphatic chain afforded 77-7, which is also an effective SK1 inhibitor; however, the N,N,N-trimethylammonium salt 77-13 is a nonselective SK inhibitor.

Fig. 2.

Effect of inhibitors on SK1 or SK2 activity (n = 3 for each compound, mean inhibition ± S.D.). Compounds were used at 50 μM. The Sph concentrations were 3 and 10 μM, corresponding to the Km values of SK1 and SK2, respectively.9,22 BML-258 at 50 μM inhibited SK1 activity by 74.5 ± 3.3%. The control is set at 100% and denotes the activity against Sph alone.

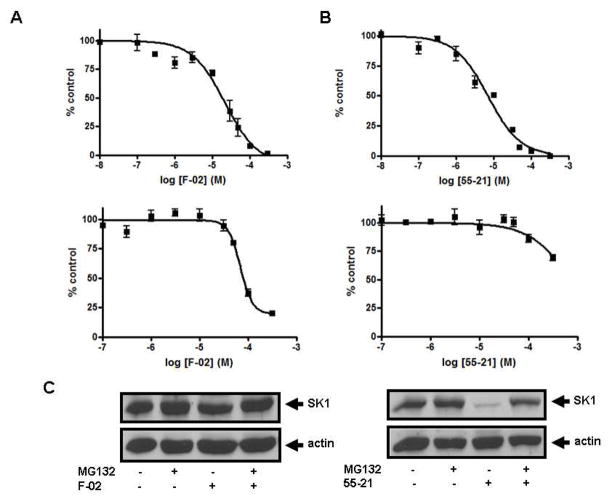

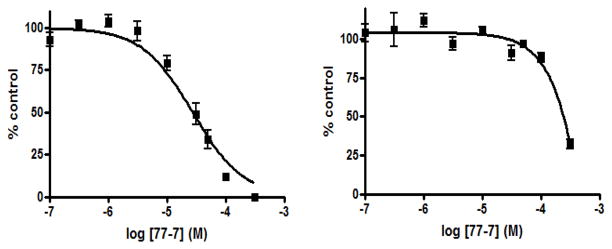

To further establish the selectivity for SK1 or SK2 of the most effective compounds identified above, we determined the relative IC50 values for F-02, 55-21, and 77-7. As shown in Fig. 3A, F-02 inhibited SK2 activity with an IC50 of 21.8 ± 4.2 μM and SK1 activity with an IC50 of 69 ± 5.5 μM. Fig. 3B shows that 55-21 inhibited SK1 activity with an IC50 of 7.1 ± 0.75 μM and SK2 activity with an IC50 of 766 ± 133 μM. 77-7 inhibited SK1 activity with an IC50 of 27.8 ± 3.2 μM and SK2 activity with an IC50 of 300 ± 62.3 μM (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Concentration-dependent inhibition of (A) SK2 activity (upper graph) and SK1 activity (lower graph) by F-02; (B) SK1 activity (upper graph) and SK2 activity (lower graph) by 55-21. Results are expressed as mean inhibition ± S.D. of control (n = 3-6); the control is set to 100% and represents the activity with Sph in the absence of inhibitor. The Sph concentrations were 3 and 10 μM, corresponding to the Km of SK1 and SK2, respectively; (C) Effect of 55-21 on SK1 expression. PASMC were treated with or without MG132 (10 μM, 30 min) before addition of 55-21 (10 μM, 24 h) or F-02 (10 μM, 24 h). Cell lysates were western blotted with anti-SK1 and anti-actin antibodies. Results are representative of three experiments.

Fig. 4.

Concentration-dependent inhibition of SK1 activity (left graph) and SK2 activity (right graph) by 77-7. Results are expressed as mean inhibition ± S.D. of control (n = 3); the control is set to 100% and represents the activity with Sph in the absence of inhibitor. The Sph concentrations were 3 and 10 μM, corresponding to the Km values of SK1 and SK2, respectively.

Next, the possibility that the compounds that bear a hydroxyl group may also serve as SK substrates was examined. At 50 μM, F01, 77-13, 67-341, and 67-302 are weak substrates of SK1 (ESI), but probably overlap the Sph binding site in SK1, thereby inhibiting catalytic phosphorylation of Sph. At 50 μM, F02 and F01 were very weak substrates of SK2 but 67-302 (cis-Sph) was efficiently phosphorylated by SK2. None of the other compounds were SK1 or SK2 substrate.

We have previously shown that inhibition of SK activity in cells with the SK inhibitors SKi, N,N-dimethyl-Sph, or FTY720 induces proteasomal degradation and removal of SK1 from PASMC and cancer cell lines.23 Removal of SK1 in response to SKi reduces intracellular S1P and increases C22:0-ceramide levels, thereby promoting apoptosis.23 Fig. 3C shows that treatment of PASMC with the SK1-selective inhibitor 55-21 (10 μM, 24 h) reduced the expression of SK1; this was reversed by pre-treatment of the cells with the proteasomal inhibitor MG132. In contrast, treatment of PASMC with the SK2-selective inhibitor F-02 was without effect on SK1 expression, suggesting that changes in ceramide-sphingosine-S1P rheostat regulated by SK2 is not accessible to the proteasome and therefore does not regulate SK1 turnover.

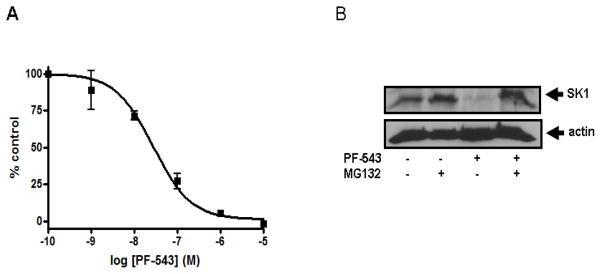

Recent studies have identified new nonlipid SK1 and SK2 inhibitors with nanomolar potency, including PF-543 and VPC96091 (see ESI for structures).24, 25 We tested the effect of PF-543 on SK1 and SK2 activity. Fig. 5 shows that PF-543 inhibited SK1 activity with an IC50 value of 28 ± 6.15 nM. This is a 10-fold lower potency than previously reported for PF-543.24 In contrast, PF-543 inhibited SK2 activity by 33.3 ± 3.0% at 5 μM and 72. 2 ± 3.4% at 50 μM (n = 3), confirming that this compound is highly selective for SK1 as previously reported.24 Interestingly, we found that treatment of PASMC with 100 nM PF-543 induced a decrease in cellular SK1 expression, which was reversed by the proteasomal inhibitor MG132 (Fig. 5). These findings indicate that inhibitor-induced proteasomal degradation of SK1 correlates with a concentration-dependent inhibition of SK1 activity.

Fig. 5.

(A) Concentration-dependent inhibition of SK1 activity with PF-543. Results are expressed as mean inhibition ± S.D. of control (n = 3-6); the control is set to 100% and represents the activity with Sph in the absence of inhibitor. The Sph concentration was 3 μM, corresponding to the Km of SK1. Effect of PF-543 on SK1 expression. (B) PASMC were treated with or without MG132 (10 μM, 30 min) before PF-543 (100 nM, 24 h). Cell lysates were western blotted with anti-SK1 and anti-actin antibodies. Results are representative of three experiments.

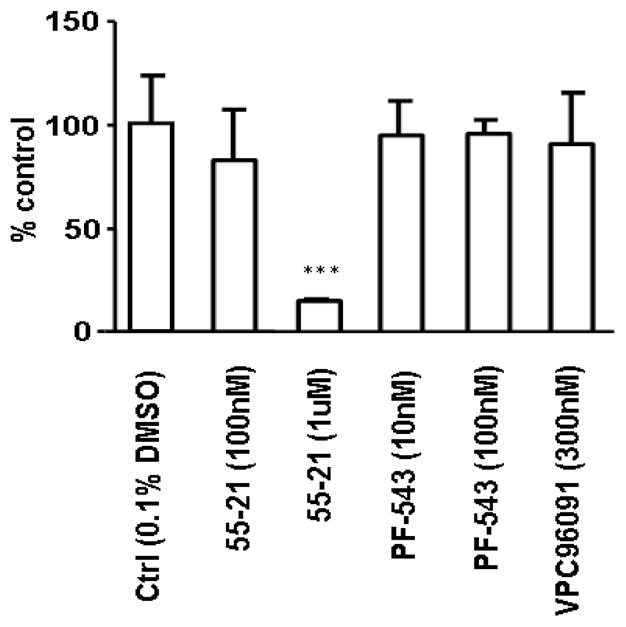

VPC96091 was used at the previously reported Ki concentration for SK1 and SK2.25 VPC96091 at 130 nM inhibited SK1 activity by 41.3 ± 3.0% (n = 3), while 1.5 μM VPC96091 inhibited SK2 activity by 73.4 ± 1.5% (n = 3). At 50 μM, VPC96091 abolished SK1 and SK2 activity (data not shown). Therefore, both PF-543 and VPC96091 are more effective inhibitors of SK1 than the new inhibitors presented herein. However, PF-543 and VPC96091 are ineffective at reducing DNA synthesis in PASMC, while 55-21 significantly inhibited DNA synthesis (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Assessment of the effects of PF-543 (10 nM and 100 nM, 24 h), VPC96091 (300 nM, 24 h), and 55-21 (100 nM and 1 μM, 24 h) on [3H]-thymidine incorporation into DNA in PASMC. Results are expressed as mean inhibition ± S.D. of control (n = 3); the control is set to 100%. *** p <0.05 versus control.

Conclusions

In summary, we have identified new SK inhibitors with isoform selectivity. Moreover, inhibition of SK1 with selective SK1 inhibitors, e.g., 55-21 and RB-005,26 is linked with ubiquitin-proteasomal degradation of SK1 that might confer enhanced efficacy of these compounds in terms of abrogating SK1 function in cells. In addition, we demonstrate here that 55-21 is effective at reducing DNA synthesis in PASMC, while more potent SK1 inhibitors, such as PF-543 and VPC96091, are not effective. There is substantial evidence to indicate that SK1 has an essential role on regulating cell growth and survival.2 For instance, siRNA knockdown of SK1 has been shown to induce ceramide-stimulated apoptosis of MCF-7 breast cancer cells.27 Therefore, while PF-543 and VPC96091 are more effective inhibitors of SK1 compared with 55-21, this enhanced binding affinity might result in a lack of specificity toward other enzymes that can bind sphingosine-based compounds, such as ceramide synthases. This might effectively negate the effect of inhibiting SK1 activity on cell growth and survival by preventing formation of ceramide from sphingosine that has accumulated as a result of inhibiting SK1 activity. Indeed, PF-543 fails to increase endogenous ceramide levels in head and neck 1483 carcinoma cells, where it lacks cytotoxicity.24 The novel compounds identified here, e.g. 55-21, have moderate potency, which might represent a more favorable profile in terms of selectively abrogating SK1 function without exhibiting ‘off-target’ effects on sphingosine/ceramide metabolizing enzymes. In this regard, 55-21 recapitulates siRNA knockdown and genetic studies in terms of reducing cell growth; thus 55-21 is expected to have utility in unraveling the functions of SK1 in inflammatory and hyperproliferative disorders. With the recent elucidation of the atomic structure of SK1,28 it may be be possible to define the binding modalities of these inhibitors in the future and to optimize the structures of novel inhibitors to achieve higher potency and selectivity.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a British Heart Foundation grant (29476) to NJP/SP and by NIH Grant HL-083187 to RB. We thank Dr. Dong Jae Baek for preparing VPC96091.

Footnotes

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: Detailed synthetic procedures and NMR spectra, and SK assay information. See DOI:

Notes and references

- 1.For recent reviews on inhibition of SK activity and alteration of S1P signaling, see: Pyne S, Bittman R, Pyne NJ. Cancer Res. 2011;71:6576. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-2364.Pitson SM, Powell JA, Bonder CS. Anti-Cancer Agents Med Chem. 2011;11:799. doi: 10.2174/187152011797655078.Orr Gandy KA, Obeid LM. Biochim Biophys Acta – Mol Cell Biol Lipids. 2013;1831:157. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2012.07.002.

- 2.Pyne S, Pyne NJ. Trends Mol Med. 2011;17:463. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2011.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van Brocklyn JR, Jackson CA, Pearl DK, Kotur MS, Snyder PJ, Prior TW. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2005;64:695. doi: 10.1097/01.jnen.0000175329.59092.2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Akao Y, Banno Y, Nakagawa Y, Hasegawa N, Kim TJ, Murate T, Igarashi Y, Nozawa Y. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;342:1284. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.02.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahmad M, Long JS, Pyne NJ, Pyne S. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2006;79:278. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2006.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sankala HM, Hait NC, Paugh SW, Shida D, Lépine S, Elmore LW, Dent P, Milstien S, Spiegel S. Cancer Res. 2007;67:10466. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gao P, Smith CD. Mol Cancer Res. 2011;9:1509. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-11-0336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paugh SW, Paugh BS, Rahmani M, Kapitonov D, Almenara JA, Kordula T, Milstien S, Adams JK, Zipkin RE, Grant S, Spiegel S. Blood. 2008;112:1382. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-02-138958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lim KG, Chaode S, Bittman R, Pyne NJ, Pyne S. Cell Signal. 2011;23:1590. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2011.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.French KJ, Zhuang Y, Maines LW, Gao P, Wang W, Beljanski V, Upson JJ, Green CL, Keller SN, Smith CD. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2010;333:129. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.163444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu K, Guo TL, Hait NC, Allegood J, Parikh HI, Xu W, Kellogg GE, Grant S, Spiegel S, Zhang S. PLoS One. 2013;8:e56471. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jarvis WD, Fornari FA, Jr, Traylor RS, Martin HA, Kramer LB, Erukulla RK, Bittman R, Grant S. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:8275. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.14.8275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dickson MA, Carvajal RD, Merrill AH, Jr, Gonen M, Cane LM, Schwartz GK. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:2484. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Soriano JM, Gonzales L, Catala AI. Prog Lipid Res. 2005;44:345. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2005.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Massard C, Salazar R, Armand JP, Majem M, Deutsch E, García M, Oaknin A, Fernández-García EM, Soto A, Soria JC. Invest New Drugs. 2012;30:2318. doi: 10.1007/s10637-011-9772-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Symolon H, Bushnev A, Peng Q, Ramaraju H, Mays SG, Allegood JC, Pruett ST, Sullards MC, Dillehay DL, Liotta DC, Merrill AH., Jr Mol Cancer Ther. 2011;10:648. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-0754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stockmann-Juvala H, Savolainen K. Human Exp Toxicol. 2008;27:799. doi: 10.1177/0960327108099525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson CR, Chun J, Bittman R, Jarvis WD. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;309:452. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.060665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stereoisomers of 4-amino-2-tetradecyltetrahydrofuran-3-ol (pachastrissamines) are inhibitors of SK and protein kinase C; see: Yoshimitsu Y, Oishi S, Miyagaki J, Inuki S, Ohno H, Fujii N. Bioorg Med Chem. 2011;19:5402. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2011.07.061.

- 20.He L, Byun HS, Bittman R. J Org Chem. 2000;65:7618. doi: 10.1021/jo001225v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hong CI, Nechaev A, Kirisits AJ, Vig R, Hui SW, West CR. J Med Chem. 1995;38:1629. doi: 10.1021/jm00010a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lim KG, Tonelli F, Li Z, Lu X, Bittman R, Pyne S, Pyne NJ. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:18633. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.220756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Loveridge C, Tonelli F, Leclercq T, Lim KG, Long S, Berdyshev E, Tate RJ, Natarajan V, Pitson SM, Pyne NJ, Pyne S. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:38841. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.127993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schnute ME, McReynolds MD, Kasten T, Yates M, Jerome G, Rains JW, Hall T, Chrencik J, Kraus M, Cronin CN, Saabye M, Highkin MK, Broadus R, Ogawa S, Cukyne K, Zawadzke LE, Peterkin V, Iyanar K, Scholten JA, Wendling J, Fujiwara H, Nemirovskiy O, Wittwer AJ, Nagiec MM. Biochem J. 2012;444:79. doi: 10.1042/BJ20111929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kennedy AJ, Mathews TP, Kharel Y, Field SD, Moyer ML, East JE, Houck JD, Lynch KR, Macdonald TL. J Med Chem. 2011;54:3524. doi: 10.1021/jm2001053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baek DJ, MacRitchie N, Pyne NJ, Pyne S, Bittman R. Chem Comm. 2013;49:2136. doi: 10.1039/c3cc00181d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Taha TA, Kitatani K, El-Alwani M, Bielawski J, Hannun YA, Obeid LM. FASEB J. 2006;20:482. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4412fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang Z, Min X, Xiao SH, Johnstone S, Romanow W, Meininger D, Xu H, Liu J, Dai J, An S, Thibault S, Walker N. Structure. 2013;21:798. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2013.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.