Abstract

“Super Power”: The application of the "supersilyl” group as carboxylic acid protecting group has been investigated. The unique properties of the “supersilyl” group enabled it to outperform typical carboxyl protecting groups, conferring extraordinary protection upon the carboxyl functionality. “Supersilyl” esters were also utilized for the first time as stable carboxylic acid synthetic equivalents in highly stereoselective aldol and Mannich reactions. The value of this methodology has been further described by the easy photo-deprotection protocol and its applications in rapid synthesis of polyketide subunits.

Keywords: carboxyl protecting group, aldol reaction, Mannich reaction, photo removable, polyketide

Historically, silyl groups have rarely been utilized as a protecting group for carboxylic acids in organic synthesis, as the Si-O bonds are too labile even under mild reaction conditions.[1,2] Similarly, the employment of silyl esters in synthetically useful organic transformations has also been underpresented.[1,2] As part of our continuing studies on tris(trialkylsilyl)silyl (“supersilyl”) group, we have developed the “supersilyl” directed aldol reactions of β-siloxy methyl ketones and cascade Mukaiyama aldol reactions, which enabled the rapid assembly of polyol motifs and expedient synthesis of polyketide natural products.[3] The “supersilyl” group, with unique electronic properties and large steric bulk, has been discovered to play a crucial role in obtaining high yields and selectivities.[3] Encouraged especially by the stability and steric encumbrance of “supersilyl” ether motifs, we reasoned that the "supersilyl" group might be able to offer the necessary robustness for silyl esters as it is well-known that the stability of silyl esters, like that of silyl ethers, parallels the steric bulk of the silyl group.[1] Herein, we are glad to report our initial efforts toward the low stability problems of silyl esters described above: 1) the use of “supersilyl” group as a highly effective carboxyl protection group and 2) the exemplificative application of “supersilyl” esters as stable synthetic equivalents of carboxylic acids in highly stereoselective aldol and Mannich reactions.

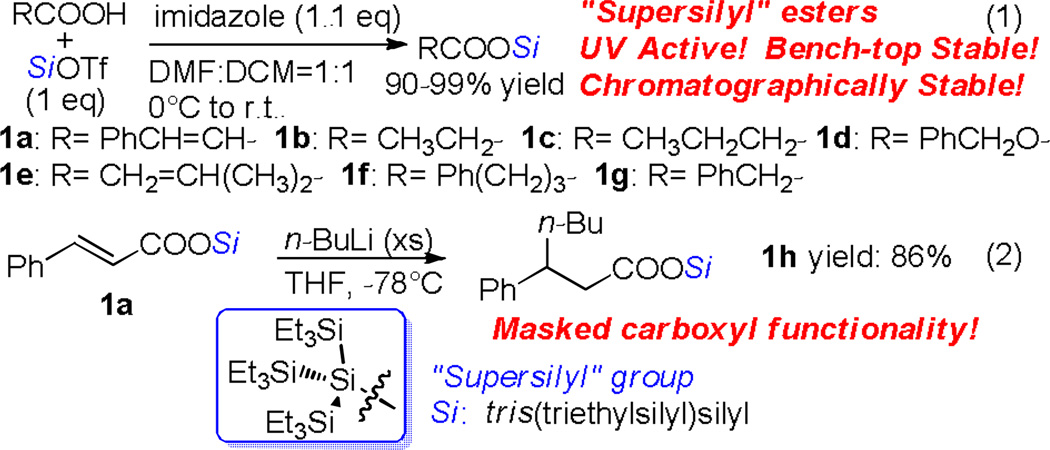

The installation of the “supersilyl” group could be simply achieved by treatment of carboxylic acids with tris(triethylsilyl)silyl triflate (generated in situ by mixing the silane with triflic acid) in the presence of imidazole (Scheme 1, eq. 1).[4] It is worth mentioning that the obtained silyl esters are UV-active due to the “supersilyl” group (allowing for straightforward TLC analysis even when the R group is aliphatic)[5] and stable for purification by chromatography. Our preliminary efforts made to evaluate the stabilities of “supersilyl” esters toward various reagents implied that the model substrate 1f is stable to excess MeMgBr, n-BuLi, DIBAL-H and LiHMDS (Table 1).[6,7] Like most known carboxyl protecting groups, this silyl group failed to offer protection against MeLi due to the rapid formation of methylated silane. Remarkably, treating 1a with n-BuLi at −78°C only led to the conjugate addition product 1g while the carboxyl group remained intact (eq. 2).[8] These results clearly showed that the “supersilyl” group confers extraordinary protection upon the carboxyl functionality. Such unprecedented stability of silyl esters may offer a high degree of synthetic flexibility and even an exciting possibility for new synthetic strategies, which thus prompted us to explore their applications in organic transformations.

Scheme 1.

“Supersilyl” esters synthesis and 1,4 addition reaction.

Table 1.

Stability examination of “supersilyl” esters.

| Reagents | 1f (0.1 M) |

|---|---|

| MeMgBr (2 eq) | No nucleophilic attack and silane methylation observed (−78°C to r.t.) |

| MeLi (2 eq) | Rapid formation of methylated silane observed at −78°C |

| DIBAL-H (2 eq) | No reduction of carboxyl functionality observed (−78°C to r.t.) |

| LiHMDS (2 eq) | No decomposition and deprotonation observed (−78°C to r.t.) |

| n-BuLi (2 eq) | No nucleophilic attack and silane alkylation observed Enolate formation observed (−78°C to −20°C) |

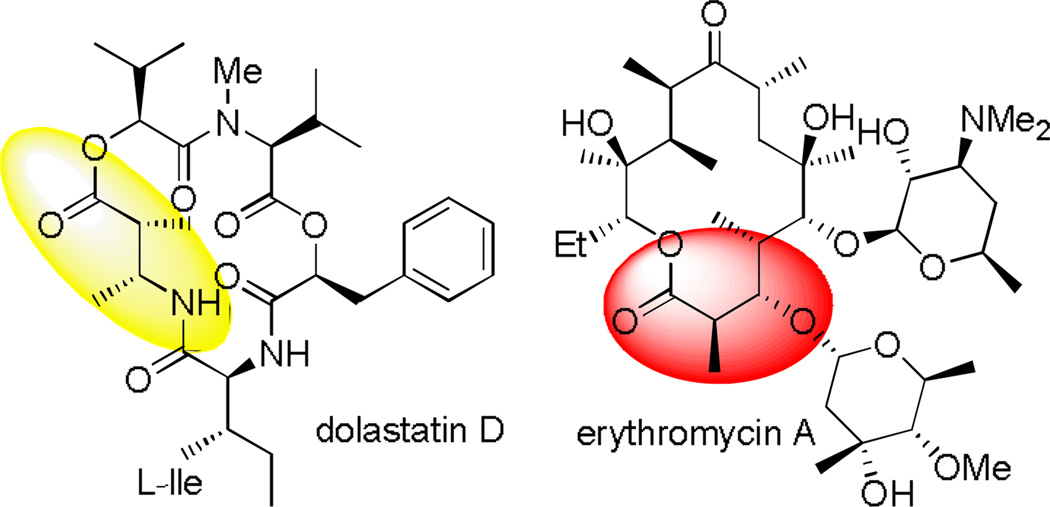

Even though the carboxyl moiety is well-protected by the “supersilyl” group, deprotonation at the α-position is still effective. Reaction of 1b with n-BuLi at −78°C followed by quenching with D2O gave the deuterium-substituted product in quantitative yield with >95% deuterium incorporation.[7] This promising result led us to first investigate the reactivity of stable “supersilyl” ester enolates. Undoubtedly, one of the most straightforward strategies for synthesizing β-amino/hydroxyl carboxylic acid derivatives is the stereoselective aldol[9,10] or Mannich[11,12] reaction of metal enolates with aldehydes or imines, respectively. Since these compounds are privileged structural motifs for biologically active molecules and natural products such as peptides[13] (dolastatin D) and polyketides[14] (erythromycin A), the development of alternative synthetic methods is still highly desirable (Figure 1). Notably, the employment of silyl groups as carboxylic acid donor groups in stereoselective metal enolate C-C bond formation reactions has never been explored to date.

Figure 1.

Dolastatin D and erythromycin A.

To our delight, the model reaction of the lithium enolate of 1b and benzaldehyde in THF gave A1 with good yield and syn-selectivity (Table 2, entry 1). Other bases including LDA, LiHMDS, t-BuLi, KHMDS and n-BuMgCl were also screened, only the t-BuLi offered comparable results (entries 2–6).[15] Switching the solvent to toluene or ether proved to be detrimental to the yield and selectivity, implying the importance of THF coordination to lithium (entries 7–8). A decreased or even reversed selectivity was observed when TMEDA or HMPA was employed as the additive (entries 9–10). The control experiment with the TIPS group gave only trace amounts of the aldol product while the rest of starting materials decomposed at −78°C (entry 11). Further optimization revealed that raising the temperature to −40°C failed to improve the results (entry 12). Despite careful screening, increasing lithiation time was finally found to be critical for obtaining high syn-selectivity (entry 13).[7]

Table 2.

Reaction condition optimization.

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | RM | Solvent | Yield(%)[a] | Syn:anti[b] |

| 1 | n-BuLi | THF | 90 | 95:5 |

| 2 | LDA | THF | 60 | 80:20 |

| 3 | LiHMDS | THF | N.R. | N.D. |

| 4 | KHMDS | THF | N.R. | N.D. |

| 5 | t-BuLi | THF | 90 | 95:5 |

| 6 | n-BuMgCl | THF | N.R. | N.D. |

| 7 | n-BuLi | Ether | 20 | 75:25 |

| 8 | n-BuLi | PhMe | trace | N.D. |

| 9 | n-BuLi/TMEDA | THF | 85 | 84:16 |

| 10 | n-BuLi/HMPA | THF | 82 | 33:67 |

| 11[c] | n-BuLi | THF | trace | N. D. |

| 12[d] | n-BuLi | THF | 91 | 75:25 |

| 13[e] | n-BuLi | THF | 86 | 99:1 |

Isolated yield.

Determined by 1H NMR of crude products.

TIPS group was used.

Temperature: −40°C.

lithiation time: 24 h.

A variety of substrates were then investigated under the optimized reaction conditions (Table 3). The aromatic aldehydes with both electron donating and withdrawing groups, possessing various substitution patterns on the phenyl ring, gave the aldol products with good yields and selectivities (entries 1–11). Subjection of the aliphatic aldehydes to standard conditions also provided the desired products in excellent selectivities (entries 12–16). In addition, conjugated aldehydes were suitable substrates to solely give 1,2 addition products (entries 17–18). When the α-oxygenated aldehyde was examined, the aldol reaction proceeded effectively to give the polyol product in 90% yield and 95:5 syn-selectivity (entry 19). Aldehydes bearing either heterocycles or naphthyl rings were also well-tolerated, delivering aldol products with slightly lower yields (entries 20–24). Essentially, the acetophenone was used as the electrophile, which led to the product with contiguous tertiary and quaternary carbon centers (entry 25). Further exploration of Silyl esters 1b–1e with diverse R1 groups also provided the aldol products with good syn-selectivities (entry 26–28). Even 1g, with a bulky benzyl substituent, could be deprotonated to form the stable enolate, giving the desired product with moderate stereoselectivity (entry 29).

Table 3.

Substrates scope for aldol reaction.

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | R1 | R2 | Yield(%)[a] | Syn:anti[b] |

| 1 | Me | Ph | 86 | 99:1 |

| 2 | Me | 2-Me-C6H4 | 75 | 99:1 |

| 3 | Me | 2-F-C6H4 | 74 | 99:1 |

| 4 | Me | 3-Me-C6H4 | 86 | 99:1 |

| 5 | Me | 3-MeO-C6H4 | 83 | 99:1 |

| 6 | Me | 3-Br-C6H4 | 90 | 99:1 |

| 7 | Me | 4-Me-C6H4 | 95 | 99:1 |

| 8 | Me | 4-F-C6H4 | 89 | 99:1 |

| 9 | Me | 4-Br-C6H4 | 87 | 99:1 |

| 10 | Me | 4-CF3-C6H4 | 77 | 99:1 |

| 11 | Me | 4-MeO-C6H4 | 89 | 99:1 |

| 12 | Me | t-butyl | 90 | 97:3 |

| 13 | Me | ethyl | 88 | 95:5 |

| 14 | Me | cyclopropyl | 87 | 97:3 |

| 15 | Me | c-hex | 90 | 99:1 |

| 16 | Me | n-C7H15 | 86 | 98:2 |

| 17 | Me | cinnamyl | 93 | 99:1 |

| 18 | Me | phenylacetylenyl | 85 | 95:5 |

| 19 | Me | BnOCH2 | 90 | 92:8 |

| 20 | Me | 1-naphthyl | 70 | 98:2 |

| 21 | Me | 2-naphthyl | 83 | 99:1 |

| 22 | Me | 2-furyl | 70 | 99:1 |

| 23 | Me | 2-thienyl | 79 | 99:1 |

| 24 | Me |  |

65 | 99:1 |

| 25 | Me | acetophenone | 66 | 95:5 |

| 26 | Et | Ph | 85 | 97:3 |

| 27 | BnO | Ph | 80 | 90:10 |

| 28 | Allyl | Ph | 72 | 90:10 |

| 29 | Bn | Ph | 86 | 86:14 |

Isolated yield.

Determined by 1H NMR of the crude products.

Next, the Mannich reactions with various N-diphenylphosphinyl (N-DPP) imines were evaluated (Table 4).[7] In all reactions of the aromatic imines, excellent stereoselectivities were achieved, while both electron-donating and -withdrawing groups had little impact (entries 1–10). The reactions of conjugated imines exclusively gave the 1,2 addition products (entries 11–12). Aliphatic imines with and without enolizable α -hydrogens all reacted with silyl ester enolates effectively (entries 13–15). For imines bearing naphthyl rings, the Mannich reactions all occurred with high selectivities (entries 16–17). Notably, heteroaryl-substituted amino acids, widely present in molecules with promising biological activities, could be constructed by this protocol in excellent stereoselectivities from heteroaromatic imines such as furyl imines and thienyl imines (entries 18–19).[13] Reaction of 1c also gave the desired β-amino silyl ester product with high syn-selectivity (entry 20).

Table 4.

Substrate scope for Mannich reaction.

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | R1 | R2 | Yield(%)[a] | Syn:anti[b] |

| 1 | Me | Ph | 88 | 99:1 |

| 2 | Me | 2-Me-C6H4 | 83 | 99:1 |

| 3 | Me | 2-F-C6H4 | 70 | 97:3 |

| 4 | Me | 3-Me-C6H4 | 79 | 99:1 |

| 5 | Me | 3-MeO-C6H4 | 78 | 99:1 |

| 6 | Me | 3-Br-C6H4 | 91 | 99:1 |

| 7 | Me | 4-Me-C6H4 | 77 | 98:2 |

| 8 | Me | 4-CF3-C6H4 | 85 | 99:1 |

| 9 | Me | 4-Br-C6H4 | 89 | 99:1 |

| 10 | Me | 4-MeO-C6H4 | 81 | 98:2 |

| 11 | Me | cinnamyl | 89 | 97:3 |

| 12 | Me | phenylacetylenyl | 75 | 91:9 |

| 13 | Me | isopropyl | 79 | 93:7 |

| 14 | Me | cyclopropyl | 80 | 97:3 |

| 15 | Me | t-butyl | 92 | 95:5 |

| 16 | Me | 1-naphthyl | 68 | 99:1 |

| 17 | Me | 2-naphthyl | 87 | 99:1 |

| 18 | Me | 2-furyl | 80 | 97:3 |

| 19 | Me | 2-thienyl | 72 | 99:1 |

| 20 | Et | Ph | 80 | 97:3 |

Isolated yield.

Determined by 1H NMR of the crude products.

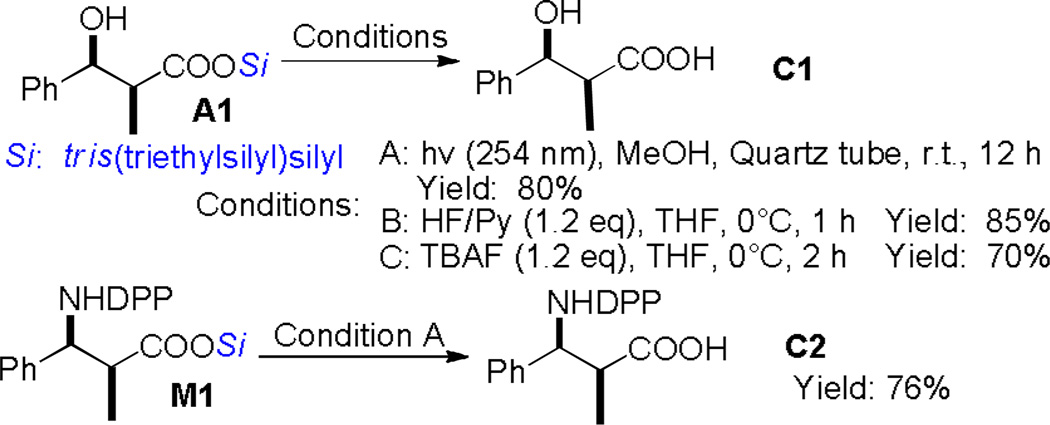

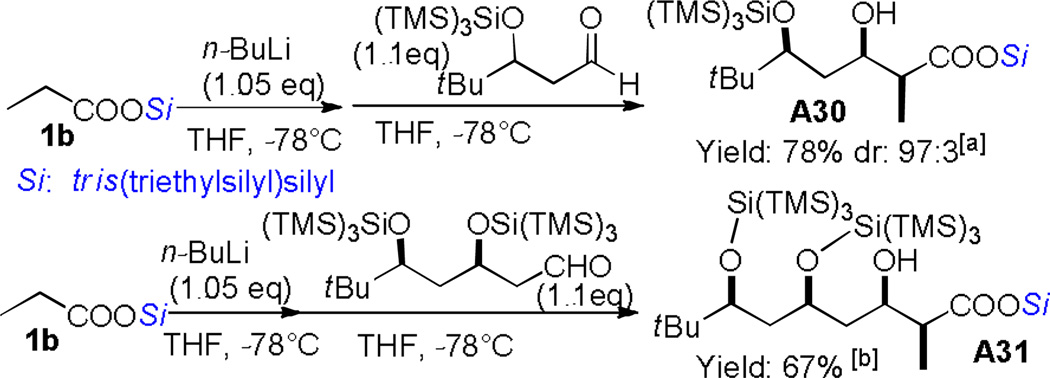

To address the synthetic utility of this protocol, the desilylation methods were studied. In addition to commonly-used fluoride methods (TBAF, HF/Py) for the removal of silyl groups, an environmentally friendly photo-desilylation condition was established.[16] Simple exposure of the “supersilyl” esters to 254 nm light from UV lamps for laboratory use could remove this unique silyl group in high efficiency (Scheme 2). Given the significance of polyketides in medicinal chemistry,[14] we recognized another attractive prospect might be the rapid synthesis of polyketide subunits with carboxyl functionalities. β- siloxy aldehydes obtained via cascade Mukaiyama aldol reactions[3a] were thus used to react with these silyl ester enolates, providing the desired polyketide analogues in good yields and selectivities (Scheme 3).

Scheme 2.

Deprotection methods.

Scheme 3.

Rapid synthesis of polyketide subunits. [a] Determined by 1H NMR of the crude product. [b] Yields for the major diastereom er. dr cannot be determined by the 1H NMR analysis.

Finally, the bulky aryl ester reported by Heathcock et al[10c,e] were examined for the Mannich reaction. The anti-product was obtained instead. Hence, we concluded that our method represents a complementary approach, favouring syn-selective products for aldol and Mannich reactions. With a more advantageous deprotection protocol, this methodology is also expected to be as broadly utilized in natural product synthesis as Heathcock’s method (Scheme 4).

Scheme 4.

anti-Selective aldol and Mannich reaction of Esters.

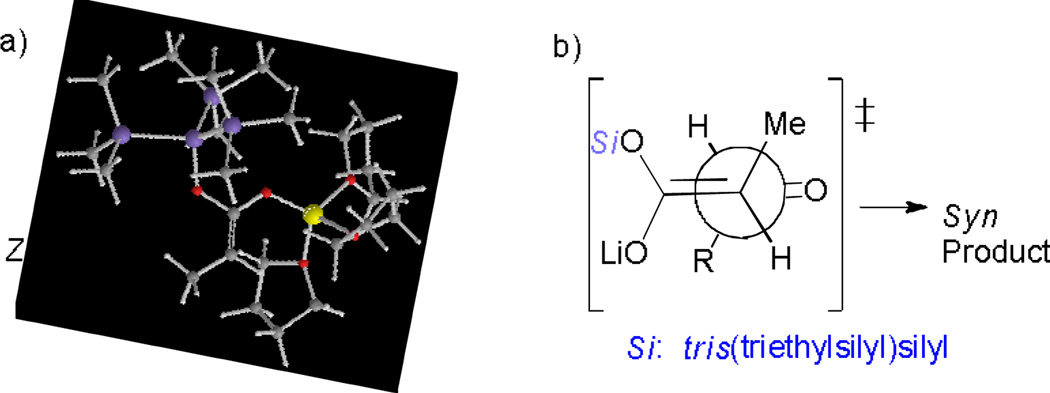

In order to shed light on the mechanism, DFT calculations were carried out to unveil the configuration of “supersilyl” ester enolates (Figure 2).[7] Computation results suggested that the solvated Z-enolate of 1b is more stable than its solvated E-enolate. Three THF molecules were coordinated to the lithium center. Based on the observed stereochemical information of aldol products, the sense of induction could not be rationalized by invoking the six-membered Zimmerman-Traxler-type transition state as suggested for the similar addition of ester enolates to aldehydes.[10c,17] Instead, the observed syn-selectivity might originate from an anti-clinal open transition state where the smallest aldehydic hydrogen is oriented over the bulky silyl group to minimize serious steric interactions.[18,19] Low diastereoselectivity obtained by the addition of HMPA might be the result of the destabilization of solvated enolates through the replacement of coordinated THF molecules.

Figure 2.

Calculated enolates configuration and proposed TS.

To summarize, we have introduced the application of the “supersilyl” group as an effective carboxyl protection group. The exceptional properties of the “supersilyl” group enabled it to outperform typical carboxyl protecting groups, especially for protection against the organometallic reagents. Moreover, “supersilyl” esters with outstanding stabilities were used as the innovative synthetic equivalents of carboxylic acids for the first time in highly stereoselective aldol and Mannich reactions, which allowed for the rapid synthesis of α-branched β-amino/hydroxyl carboxylic acid derivatives in uniformly good yields and diastereoselectivities. The value of this methodology has been highlighted via the efficient photo-deprotection protocol and its applications in rapid synthesis of polyketide subunits. This new “supersilyl” carboxyl protection group is expected to be of broad utilities in organic synthesis. Future work will focus on discovering new chemistry of “supersilyl” esters.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Support of this work was provided by NIH (P50 GM086 145-01). JJT is grateful for fruitful discussions with Dr. B. J. Albert, Dr. Y. Yosuke, Dr. S. Hirashima, P. B. Brady and Prof. S. A. Kozmin.

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://www.angewandte.org

Contributor Information

Jiajing Tan, Department of Chemistry, The University of Chicago 5735 South Ellis Avenue, Chicago, IL, 60637 (USA).

Matsujiro Akakura, Department of Chemistry, Aichi University of Education Igaya-cho, Kariya, 448-8542 (Japan).

Hisashi Yamamoto, Email: yamamoto@uchicago.edu, Department of Chemistry, The University of Chicago 5735 South Ellis Avenue, Chicago, IL, 60637 (USA); Molecular Catalyst Research Center, Chubu University, 1200 Matsumoto, Kasugai 487-8501 Japan.

References

- 1.(a) Kocienski P. Protecting Groups. 3rd ed. Thieme: Stuttgart; 2005. [Google Scholar]; (b) Wuts PGM, Greene TW. Greene’s Protective Groups in Organic Synthesis. 4th ed. New York: Wiley-Interscience; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Corey EJ, Kim CU. J. Org. Chem. 1973;38:1233. doi: 10.1021/jo00946a041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Iwasaki A, Kondo Y, Maruoka K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:10238. [Google Scholar]; (c) Liang H, Hu L, Corey EJ. Org. Lett. 2011;13:4120. doi: 10.1021/ol201640y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Boxer M, Yamamoto H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:48. doi: 10.1021/ja054725k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Boxer M, Yamamoto H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:2762. doi: 10.1021/ja0693542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Boxer M, Yamamoto H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:1580. doi: 10.1021/ja7102586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Albert BJ, Yamamoto H. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010;49:2747. doi: 10.1002/anie.200907076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Yamaoka Y, Yamamoto H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:5354. doi: 10.1021/ja101076q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Albert BJ, Yamaoka Y, Yamamoto H. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:2610. doi: 10.1002/anie.201007210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Saadi J, Akakura M, Yamamoto H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:14248. doi: 10.1021/ja2066169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Brady PB, Yamamoto H. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51:1942. doi: 10.1002/anie.201108325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Corey EJ, Venkateswarlu A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1972;94:6190. [Google Scholar]; (b) Tacke R, Lange H. Chem. Ber. 1983;116:3685. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramsey BG. J. Organomet. Chem. 1974;67:C67. [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Hashimoto T, Takagaki T, Kimura H, Maruoka K. Chem. Asian J. 2011;6:1936. doi: 10.1002/asia.201100172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Bellassoued M, Grugler J, Lensen N, Catheline A. J. Org. Chem. 2002;67:5611. doi: 10.1021/jo020128u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Corriu RJP, Lanneau GF, Perrot M. Tetrahedron Lett. 1987;28:3841. [Google Scholar]; (d) Larson GL, Ortiz M, Rodriguez de Roca M. Synth. Commun. 1981;11:583. [Google Scholar]

- 7.For details, see Supporting Information.

- 8.Cooke MP., Jr J. Org. Chem. 1986;51:1637. [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Evans DA, Nelson JV, Taber TR. Topics in Stereochemistry. Vol. 13. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 1982. p. 1. [Google Scholar]; (b) Heathcock CH. Ch. 2. In: Morrison JD, editor. Asymmetric Synthesis. Vol. 3. New York: Academic Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]; (c) Heathcock CH. In: Comprehensive Organic Synthesis. Trost BM, Fleming I, editors. Vol. 2. Oxford: Pergamon Press; 1991. p. 181. [Google Scholar]; (d) Mahrwald R. Modern Aldol Reactions. Vol. 1–2. KGaA., Weinheim: Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co; 2004. [Google Scholar]; (e) Trost BM, Brindle CS. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010;39:1600. doi: 10.1039/b923537j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.(a) Buse CT, Heathcock CH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1977;99:8109. [Google Scholar]; (b) Heathcock CH, Buse CT, Kleschick WA, Pirrung MC, Sohn JE, Lampe J. J. Org. Chem. 1980;45:1066. [Google Scholar]; (c) Pirrung MC, Heathcock CH. J. Org. Chem. 1980;45:1727. [Google Scholar]; (d) Heathcock CH, Hagen JP, Jarvi ET, Pirrung MC, Young SD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1981;103:4972. [Google Scholar]; (e) Heathcock CH, Pirrung MC, Montgomery S, Lampe HJ. Tetrahedron. 1981;37:4087. [Google Scholar]; (f) Heathcock CH, Pirrung MC, Young SD, Hagen JP, Jarvi ET, Badertscher U, Marki H-P, Montgomery SH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1984;106:8161. [Google Scholar]; (g) Ruano JLG, Barros D, Maestro MC, Araya-Maturana R, Fischer J. J. Org. Chem. 1996;61:9462. [Google Scholar]; (h) Dixon DJ, Ley SV, Polara A, Sheppard TD. Org. Lett. 2001;3:3749. doi: 10.1021/ol016707n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Evans DA, Helmchen G, Rueping M. In: Asymmetric Synthesis-The Essentials. Christmann M, Brase S, editors. Vol. 3. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH & Co; 2007. [Google Scholar]; (j) Khatik GL, Kumar V, Nair VA. Org. Lett. 2012;14:2442. doi: 10.1021/ol300949s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Kleinmann EF. Ch. 4.1. In: Trost BM, Flemming I, editors. Comprehensive Organic Synthesis. Vol. 2. New York: Pergamon Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]; (b) Arend M, Westerman B, Risch N. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1998;37:1044. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19980504)37:8<1044::AID-ANIE1044>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Kobayashi S, Ishitani H. Chem. Rev. 1999;99:1069. doi: 10.1021/cr980414z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Denmark S, Nicaise OJ-C. In: Comprehensive Asymmetric Catalysis. Jacobsen EN, Pfaltz A, Yamomoto H, editors. Vol. 2. Berlin: Springer; 1999. p. 93. [Google Scholar]; (e) Ting A, Schaus SE. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2007:5797. [Google Scholar]; (f) Verkade JMM, VanHemert LJC, Quaedflieg PJLM, Rutjes FPJT. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008;37:29. doi: 10.1039/b713885g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.(a) Fujieda H, Kanai M, Kambara T, Iida A, Tomioka K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:2060. [Google Scholar]; (b) Saito S, Hatanaka K, Yamamoto H. Org. Lett. 2000;2:1891. doi: 10.1021/ol000099e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Palomo C, Oiarbide M, Landa A, Gonzalez-Rego MC, Garcia JM, Gonzalez A, Odriozola JM, Martin-Pastor M, Linden A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:8637. doi: 10.1021/ja026250s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Davis FA, Deng J. Org. Lett. 2004;6:2789. doi: 10.1021/ol048981y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Hata S, Iguchi M, Iwasawa T, Yamada K, Tomioka K. Org. Lett. 2004;6:1721. doi: 10.1021/ol049675n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Morimoto H, Wiedemann SH, Yamaguchi A, Harada S, Chen Z, Matsunaga S, Shibasaki M. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006;45:3146. doi: 10.1002/anie.200600227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Tiong EA, Gleason JL. Org. Lett. 2009;11:1725. doi: 10.1021/ol802643k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Colpaert F, Mangelinckx S, De Kimpe N. Org. Lett. 2010;12:1904. doi: 10.1021/ol100073y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.(a) Nussbaum FV, Spiteller P. In: Highlights in Bioorganic Chemistry: Methods and Application. Schmuck C, Wennemers H, editors. Weinheim, Germany: Wiley-VCH; 2003. p. 63. [Google Scholar]; (b) Lelais G, Seebach D. Biopolymers. 2004;76:206. doi: 10.1002/bip.20088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Kuhl A, Hahn MG, Dumic M, Mittendorf J. Amino Acids. 2005;29:89. doi: 10.1007/s00726-005-0212-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.(a) Rychnovsky SD. Chem. Rev. 1995;95:2021. [Google Scholar]; (b) Rohr J. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2000;39:2847. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20000818)39:16<2847::aid-anie2847>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Koskinen AMP, Karisalmi K. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2005;34:677. doi: 10.1039/b417466f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Hertweck C. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:4688. doi: 10.1002/anie.200806121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Pal S. Tetrahedron. 2006;62:3171. [Google Scholar]

- 15.(a) Snieckus V. Chem. Rev. 1990;90:879. [Google Scholar]; (b) Clayden J. Organolithiums: Selectivity for Synthesis. Amsterdam: Pergamon; 2002. [Google Scholar]; (c) Bakker WII, Wong PL, Snieckus V, Warrington JM, Barriault L. In: e-EROS. Paquette LA, editor. New York: Wiley; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 16.(a) Pillai VNR. Synthesis. 1980:1. [Google Scholar]; (b) Pirrung MC, Lee YR. J. Org. Chem. 1993;58:6961. [Google Scholar]; (c) Brook MA, Balduzzi S, Mohamed M, Gottardo C. Tetrahedron. 1999;55:10027. [Google Scholar]; (d) Klan P, Zabadal M, Heger D. Org. Lett. 2000;2:1569. doi: 10.1021/ol005789x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Pirrung MC, Fallon L, Zhu J, Lee YR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:3638. doi: 10.1021/ja002370t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Givens RS, Conrad PG, II, Yousef AL, Lee J-I. In: Photoremovable Protecting Groups in CRC Handbook of Organic Photochemistry and Photobiology. 2nd Ed. Horspool WM, editor. Ch. 69. 2003. p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- 17.(a) Zimmerman HE, Traxler MD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1957;79:1920. [Google Scholar]; (b) Dubois JE, Fort JF. Tetrahedron. 1972;28:1653. [Google Scholar]; (c) Dubois JE, Fort JF. Tetrahedron. 1972;28:1665. [Google Scholar]; (d) Dubois JE, Fellman PCR. Acad. Sci. 1972;274:1307. [Google Scholar]; (e) Dubois JE, Fellman P. Tetrahedron Lett. 1975:1225. [Google Scholar]

- 18.This model could be used to rationalize the unique syn-selectivity for Mannich reaction. However, the observed syn-selectivity could possibly originate from cyclic- or twist-boat TS. For references, see: Denmark SE, Henke BR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991;113:2177. Hoffmann RW, Ditrich K, Froech S. Tetrahedron. 1985;41:5517.

- 19.Williams DR, Donnell AF, Kammler DC. Heterocycles. 2004;62:167. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.