Abstract

Background

Prospective data on viral etiology and clinical characteristics of bronchiolitis and upper respiratory illness in infants is limited.

Methods

This prospective cohort enrolled previously healthy term infants during inpatient or outpatient visits for acute upper respiratory illness (URI) or bronchiolitis during September - May 2004–2008. Illness severity was determined using an ordinal bronchiolitis severity score. Common respiratory viruses were identified by real-time RT-PCR.

Results

Of 648 infants, 67% were enrolled during inpatient visits and 33% during outpatient visits. Seventy percent had bronchiolitis, 3% croup, and 27% URI. Among infants with bronchiolitis, 76% had RSV, 18% HRV, 10% influenza, 2% coronavirus, 3% HMPV, and 1% PIV. Among infants with croup, 39% had HRV, 28% PIV, 28% RSV, 11% influenza, 6% coronavirus, and none HMPV. Among infants with URI, 46% had HRV, 14% RSV, 12% influenza, 7% coronavirus, 6% PIV, and 4% HMPV. Individual viruses exhibited distinct seasonal, demographic, and clinical expression.

Conclusions

The most common infections among infants seeking care in unscheduled medical visits for URI or bronchiolitis were RSV and HRV. Demographic differences were observed between patients with different viruses, suggesting that host and viral factors play a role in phenotypic expression of viral illness.

Keywords: bronchiolitis, croup, URI, rhinovirus, respiratory syncytial virus

Introduction

Bronchiolitis, a lower respiratory infection in infants presenting with wheezing, rales, and respiratory distress, causes a significant burden of clinical visits and hospitalizations during infancy. Bronchiolitis has typically been associated with respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection1,2, but a number of studies show that human rhinovirus (HRV) and other viruses are also important causes of bronchiolitis.3–7 These acute respiratory viral infections have additional long-term clinical significance, as other studies have found that infant wheezing with each of these viruses is linked with subsequent development of childhood asthma.8–11 We sought to determine the viral etiologies of unscheduled visits for bronchiolitis and upper respiratory illness (URI) among term otherwise healthy infants, and to assess clinical and demographic factors among infants infected by different viruses.

Methods

Study Population

The Tennessee Children’s Respiratory Initiative (TCRI) is a longitudinal prospective investigation of term, otherwise healthy infants and their biological mothers, the methods for which have been previously described.12 The primary goals of the cohort are to investigate the acute and the long-term health consequences of varying severity and etiology of viral respiratory tract infections and other environmental exposures on the outcomes of allergic rhinitis and early childhood asthma, and to identify the profile of children at greatest risk of developing asthma following infant respiratory viral infection.12 Clinical biospecimens and clinical data available from the TCRI were used for this study. Infants ≤12 months old were enrolled at the time of a clinical visit (hospitalization, emergency department (ED) visit or outpatient visit) with a diagnosis of bronchiolitis or URI from September through May 2004–2008. Inclusion criteria included: gestational age >37 weeks, birth weight >2275 grams, previously healthy infant, birth through 12 months of age during acute respiratory illness enrollment visit, biological mother available to complete skin testing and questionnaire, presumed viral bronchiolitis, lower respiratory tract illness (LRTI), or URI (as outlined below). Exclusion criteria included: adopted or foster child, unable to obtain maternal history, significant comorbidities or cardiopulmonary disease, ever received one or more doses of palivizumab, prior study inclusion, fever and neutropenia, children whose parents or guardians were not able to understand consent process, or language barrier.12 Demographic and clinical data were collected using standardized forms, and nasal/throat swabs were obtained for viral testing. The Vanderbilt Institutional Review Board approved the study and parents provided written informed consent for study participation.

Respiratory illness etiology and severity ascertainment

Acute respiratory illness was defined based on both admitting physician diagnosis and documentation of symptoms with duration <11 days; to receive this diagnosis, infants had to have at least two of the following: cough, nasal congestion, rhinorrhea, wheezing, or dyspnea, fever and be either hospitalized for at least 23 hours, have an ED visit, or have an acute care clinic visit. The discharge diagnosis and supporting clinical parameters of the infant acute respiratory illness visit were reviewed to confirm whether each child had bronchiolitis, URI, or another diagnosis. Bronchiolitis was defined as lower respiratory infection in infants presenting with wheezing, rales, and respiratory distress. URI was defined as nasal congestion, rhinorrhea, cough, and/or fever without associated wheezing or dyspnea. Bronchiolitis and URI were defined using both the physician discharge diagnosis, as well as post-discharge chart review. Those cases that were not clearly identified as either bronchiolitis or URI were reviewed by a panel of pediatricians who determined whether the illness represented bronchiolitis, URI, croup or other (which included those that could not be categorized with the available clinical information).

Infant acute respiratory illness severity

Acute respiratory illness severity was determined using an ordinal bronchiolitis score that incorporates admission information on respiratory status into a score ranging from 0 to 12 (12 being most severe).13,14 Categories considered included respiratory rate (<30, 31–45, 46–60, >60 breaths/minute), flaring or retractions (none, mild, moderate, severe), oxygen saturation >95, 90–94, 85–89, <85 % in room air), and wheezing (none, end-expiratory with stethoscope only, full expiratory with stethoscope only, audible without stethoscope or markedly decreased air exchange or auscultation). A score of 0, 1, 2, or 3 was given for each of the four categories, with a maximum total score of 12 indicating most severe.13,14

Viral testing

Nasal and throat swabs were obtained from ill infants by trained nurses, combined, and placed together into viral transport medium. Specimens were taken immediately to the lab on ice, divided into aliquots, and stored at −80°C until processed. RNA was extracted from 200 μl of specimen on a Roche MagNApure LC automated nucleic acid extraction instrument and real-time RT-PCR for the detection of HRV, RSV, influenza A and B, parainfluenza virus (PIV) 1-3, human metapneumovirus (HMPV), and coronaviruses (NL, OC43, 229E) were performed as previously described.15–19 Each viral RT-PCR was capable of detecting <50 genome copies per reaction and was highly sensitive and specific, as described.

Demographic and clinical measures

The assessment of other demographic characteristics of the cohort has been previously described12, and includes personal and family history of allergic rhinitis, asthma, and atopic dermatitis; infant age, birth weight, sex, ethnicity; insurance type, maternal age, maternal education, smoking during pregnancy or at time of enrollment, infant feeding method, daycare attendance, and number of other children in home.

Statistical Methods

Host factors were presented using median and interquartile ranges [IQR] or frequencies and proportions as appropriate. Demographic and clinical factors were described among different viruses by type of acute respiratory illness (URI versus bronchiolitis) and similar analyses were performed by whether admission was inpatient or outpatient. Analyses are presented as overall detected virus or separately without co-infections included for optimal description of the clinical infection. In analysis restricted to the viral groups without coinfection for other tested viruses, we compared host factors mentioned above and severity of bronchiolitis by virus types using the Chi-square test for categorical variables and Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables. We examined the variation of overall viral detection by year graphically. All analyses used a 5% two-sided significance level and were performed with R version 2.12.1 (www.r-project.org, R Development Core Team (2009); Vienna, Austria).

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics of cohort

A total of 648 infants with bronchiolitis, croup, or URI were enrolled during four respiratory viral seasons from 2004–2008; 67% were enrolled during hospitalizations and 33% were enrolled during outpatient visits. Median maternal age was 25 years [IQR: 22.0, 30.0]. Twenty-two percent of infants were black, 13% Hispanic, 52% white, and 12% were other race/ethnicity.

Median birth weight was 3317 grams [IQR: 3005, 3643], and 44% of infants were female. Fifty-six percent of infants were breastfed, 24% attended daycare, and 56% were ever exposed to household tobacco smoke (30% had current maternal smoking). Nineteen percent of infants had a mother with asthma, and 49% had a mother with atopy. Thirty-nine percent of infants had a history of prior wheezing.

Respiratory viruses detected by type and severity of illness

Overall, 86% of infants had a study virus detected: 58% RSV, 26% HRV, 11% influenza, 4% coronavirus, 3% HMPV, and 3% PIV.

Among the 432 infants who were hospitalized, 392 had bronchiolitis, 11 croup, and 29 URI. Overall proportions of each virus within diagnostic categories are listed in Table 1. Among the hospitalized infants with bronchiolitis (N=392), illnesses were associated with the following viruses: 79% RSV, 17% HRV, 10% influenza, 3% coronaviruses, 2% HMPV, and 1% PIV. Among hospitalized infants with URI (N=29), the following viruses were identified: 10% RSV, 45% HRV, 24% influenza, 7% coronaviruses, and no HMPV or PIV. Among the outpatient infants with bronchiolitis (N=63), 54% had RSV, 22% HRV, 8% influenza, 8% HMPV, 3% coronaviruses, and 3% PIV. Among the outpatient infants with URI (N=146), the following viruses were detected: 15% RSV, 47% HRV, 9% influenza, 8% coronaviruses, 8% PIV, and 5% HMPV.

Table 1.

Viral etiology of acute respiratory episode type.

| Viral etiology* | URI (n= 175) n (%) |

Croup (n= 18) n (%) |

Bronchiolitis (n= 455) n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human rhinovirus | 63 (36%) | 5 (28%) | 41 (9%) |

| RSV (A/B) | 11 (6%) | 3 (17%) | 268 (59%) |

| Influenza virus (A/B) | 10 (6%) | 1 (6%) | 10 (2%) |

| Human metapneumovirus | 4 (2%) | 0 | 5 (1%) |

| Human coronaviruses (HCOV OC43, 229E, NL) | 8 (5%) | 0 | 0 |

| Parainfluenza viruses (PIV 1-3) | 8 (5%) | 3 (17%) | 3 (1%) |

| HRV/RSV coinfection | 7 (4%) | 1 (6%) | 30 (7%) |

| Other virus or other coinfection** | 19 (11%) | 3 (17%) | 54 (12%) |

| Study virus negative | 45 (26%) | 2 (11%) | 43 (9%) |

Coinfections excluded, except where labeled.

“Other” includes human coronaviruses (229E, OC43, NL), human metapneumovirus, and parainfluenza viruses 1–3, and coinfections other than HRV-RSV.

Bronchiolitis

Of 455 infants with bronchiolitis (hospitalized and outpatient), 76% had RSV (59% RSV only), 18% HRV (9% HRV only), 10% influenza (2% influenza only), 2% coronavirus (none with coronavirus only), 1% HMPV (all HMPV only), and 1% PIV (all PIV only). Some children had more than one virus co-detected, including 7% with HRV and RSV and 12% with other virus co-detection. Nine percent had no study virus detected.

Croup

Of 18 infants with croup (hospitalized and outpatient), 39% had HRV (28% HRV only), 28% PIV (17% PIV only), 28% RSV (17% RSV only), 11% (2/18) influenza (6%, 1/18, influenza only), 6% coronavirus (none with coronavirus only), and none had HMPV. Some infants with croup had more than one virus co-detected, including 17% with HRV and RSV and 17% with other coinfections. Eleven percent had no study virus detected.

URI

Of 175 infants with URI (17% hospitalized and 83% outpatient), 46% had HRV (36% HRV only), 14% RSV (6% RSV only), 11% influenza (6% influenza only), 8% coronavirus (5% coronavirus only), 6% PIV (5% PIV only), and 4% HMPV (2% HMPV only). Some infants with URI had more than one virus co-detected, including 4% with HRV and RSV, and 11% with other coinfection. Twenty-six percent tested negative for study virus.

Infant age and viral etiology of respiratory illness

Study viruses associated with illness differed by age category. Overall single study virus association with illness and age category are illustrated in Supplemental Digital Content 1 (Figure). As expected, RSV was the most common sole virus detected in infants < 6 months with bronchiolitis (63%) (Fig. A, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/INF/B584; Respiratory viruses associated with clinical diagnoses, by age category 0–6 months). However, 7% of infants <6 months with bronchiolitis had sole HRV detected. Among infants 6–12 months old, 42% had RSV and the proportion of HRV bronchiolitis was 17% (Fig. B, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/INF/B584; Respiratory viruses associated with clinical diagnoses, by age category 6–12 months.). A surprising number of infants diagnosed with croup had HRV detected (28%). URI was associated with multiple viruses, though HRV was most common.

Hospitalizations

Among hospitalized patients, when assessed by age group, 59% of infants 0–6 months of age had RSV alone (214/360) and 9% with HRV alone (34/360), excluding co-infections. Similarly, among infants 6–12 months of age 42% (30/71) had RSV while 18% (13/71) had HRV. Among hospitalized infants bronchiolitis was the predominant diagnosis (91% before age 6 months and 90% after 6 months).

Outpatients

Among outpatient visits before age 6 months, 29% were detected to have HRV while 23% had RSV. Between 6 and 12 months of age 29% were detected with HRV (34/118) and 13% with RSV, (15/118). URI was a more common diagnosis among outpatients in both infant age groups (63% and 71% before and after 6 months, respectively).

Demographic and clinical characteristics varied by respiratory viral etiology and disease severity

Demographic and clinical characteristics of infants with URI or bronchiolitis, by viral etiology and excluding coinfections, are listed in Table, Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/INF/B585. Among infants with URI, there were not significant maternal or infant factors assessed that differed between infants with specific viruses.

Characteristics of infants with bronchiolitis

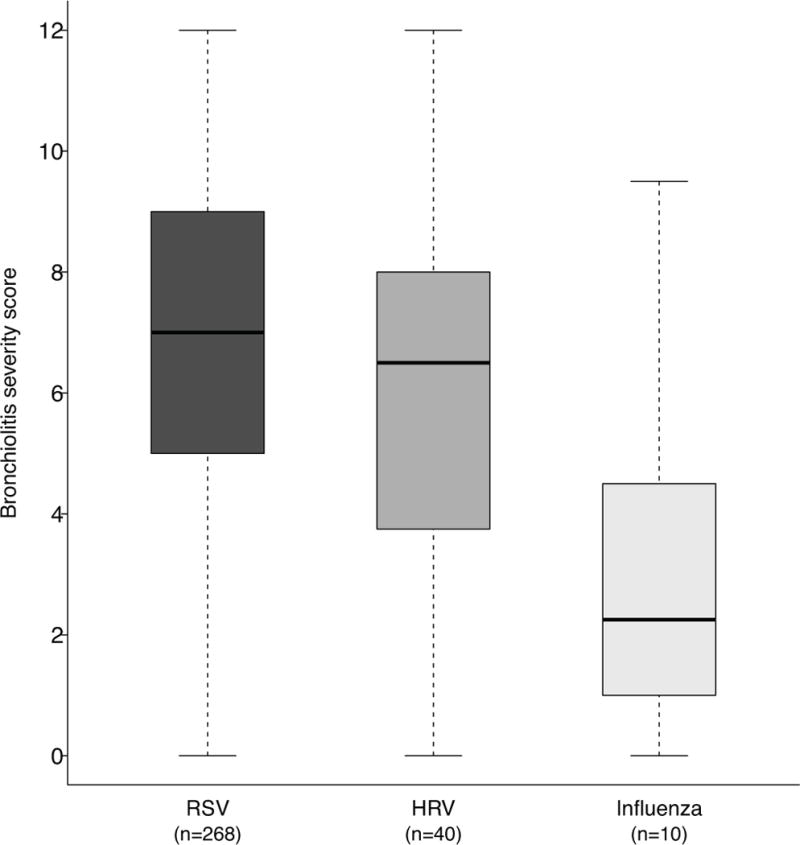

There was significant variation in age between infants presenting with bronchiolitis associated with different viruses: infants with RSV were youngest, followed by HRV, then influenza and other viruses (p=0.004). Eighty-two percent of infants with bronchiolitis had ≥ 1 other child in the home. Infants with RSV were less likely to have a prior history of wheezing than infants with any other or no study virus (p=0.002). Infants with HRV were more likely to have been treated for wheezing than infants with any other virus or no study virus (p=0.028). Infants with RSV were most likely to be hospitalized (p=0.013) and as depicted in Figure 1, infants with RSV had higher bronchiolitis severity scores with a median of 7 [IQR:5,9], vs. infants with HRV median 6.5 [IQR:4,8], or influenza 2 [IQR:1.5,2.5].

Figure 1.

Bronchiolitis severity score, by viral etiology.

Seasonality of respiratory viruses

The seasonality of each virus identified in URI and bronchiolitis is illustrated in Figure 2. HRV was detected throughout the study months from September through May with an overall peak in November. RSV was detected predominantly from December through February, and influenza was detected primarily during the winter months. Seasonality of viral detection among children with bronchiolitis is depicted, by year, in Figure 3. Almost all PIV1 were detected in a single year, 2005–2006 (data not shown).

Figure 2.

A. Seasonality of HRV, influenza, and RSV-associated LRTI in infants over 4-year period. Number detected by etiology and month, including coinfections.

B. Seasonality of HRV, influenza, and RSV-associated URI in infants over 4-year period. Number detected by etiology and month, including coinfections.

C. Seasonality of coronavirus, metapneumovirus, and parainfluenza virus- associated ARI in infants over 4-year period. Number detected by etiology and month, including coinfections.

Figure 3.

Seasonality of HRV, influenza, and RSV-associated bronchiolitis in infants, by study year. Number detected by etiology and month, including coinfections.

Discussion

We conducted a prospective, four-year summary of the viral epidemiology of infant bronchiolitis, croup, and URI in acute medical visits of term otherwise healthy infants. Our population over-sampled hospitalized infants and included about 70% hospitalized infants and 30% outpatients. Differences were identified between clinical and demographic features associated with different respiratory viruses in these non-high-risk infants.

Of the infants with bronchiolitis in our study, 59% had RSV alone, 9% had HRV alone and 7% had HRV/RSV coinfection. Other studies20,21,22 of children <2 years with bronchiolitis have reported similar proportions of RSV and HRV. However, these reports included children up to age two years; we found that HRV is a more common pathogen with advancing infant age. Thus, while RSV is the predominant virus detected in infants with bronchiolitis, HRV is associated with a substantial proportion of bronchiolitis, becoming more common with advancing infant age. Among infants hospitalized with bronchiolitis, a higher proportion was RSV-associated bronchiolitis than among infants with bronchiolitis seen as outpatients, similar to other studies. The proportion of non-RSV viruses detected in bronchiolitis was similar between this and other studies, though one study23 of outpatient infants with wheezing detected higher rates of HRV.

Infants in our study with clinically diagnosed croup had a variety of viruses detected, with HRV as the sole infection in 28%, RSV in 17%, influenza in 6%, PIV in 17%, and HRV/RSV coinfection in 6% of infants. While croup is a diagnosis often associated with PIV, others have also found non-PIV viruses linked with croup. Sung et al.21 reported that among 182 children hospitalized with croup, 24% had PIV1 and 8% PIV3, 17% had coronavirus NL63, 14% influenza A, 12% HRV, and 8% RSV. These findings underscore the importance of multiple viruses in croup and confirm that HRV should be added to the list of viruses associated with croup.

Finally, of infants in our cohort with URI, 36% had HRV alone, with other viruses each accounting for 2–6% excluding co-infections. Others have reported high rates of HRV among infants at high atopic risk with URI, including an Australian study23 that found 51% to have HRV, 9% RSV, and 5% PIV. The reason for higher HRV detection in their cohort could be related to enrolling infants at high risk for atopy, which is also consistent with other data from our group.2 Thus, while URI is less serious, these data show that HRV is associated with a substantial burden of acute illness in infants.

In our study of hospitalized and outpatient infants with respiratory illness, the viruses exhibited distinct seasonality. HRV, RSV, and influenza exhibited seasonal peaks, with HRV peaking during spring and fall, while RSV and influenza both predominated in winter months. Interestingly, all of the PIV-positive specimens were seen in a single year, 2005–2006. In one prospective population-based US study24, PIV-1 circulated in alternate odd years in the fall. Thus, studies of PIV epidemiology should include multiple seasons to avoid underestimating the burden of disease, and ideally year-round surveillance, which our study did not include. In our study, the peak of HMPV detection was in February and March, slightly earlier than a population-based study25 over 2 years in multiple US cities that found a peak of HMPV-associated hospitalizations between March and May.

Demographic factors were associated with infection by individual viruses in infants with bronchiolitis, but not URI. Bronchiolitis with RSV was associated with younger infant age, and bronchiolitis with HRV was associated with older infant age. HMPV was associated with increased maternal age and education, but the number of infants with HMPV-associated bronchiolitis was few. Detection of any virus was associated with the presence of other children in the home, implicating community spread of viruses and the value of hygiene and reduction of exposure as preventive measures.

Certain clinical factors studied were also significantly associated with individual virus detection in bronchiolitis. Infants with RSV were more likely to have no history of prior wheezing, compared to infants with HRV who were more likely to have a history of prior wheezing. Our findings are consistent with prior studies19,20 suggesting that RSV is likely to be associated with more severe disease in younger infants even if otherwise healthy, and that HRV causes more significant clinical illness in older infants at high risk for atopy with a history of prior wheezing. Korppi et al.26 compared infants < 24 months of age with HRV vs. RSV-associated wheezing and reported that infants with HRV were older and more often had atopic dermatitis and eosinophilia. These data are consistent with our finding2 that infants with HRV-associated respiratory illness are older and that an atopic profile in the mother may be an important risk factor for more severe HRV-associated infant disease.

Coinfection did not appear to increase risk for bronchiolitis severity in our study, though the numbers were small. Studies of the clinical importance of coinfection are conflicting. While some23 have reported dual infection to be associated with increased clinical severity, as evidenced by severity scores and days hospitalized, others21,27 have not.

Study Limitations

Despite the strengths of our prospective cohort study, there are limitations. First, this study cannot delineate population-based rates of viral-associated bronchiolitis and URI, as the cohort did not equally enroll hospitalized and non-hospitalized infants, with nearly two-thirds of the cohort being hospitalized infants, thus over-representing infants with bronchiolitis. Further, we evaluated only one geographic site. The percentage of children enrolled in Medicaid was higher than that of the general US population and higher than the proportion in Tennessee. This may affect demographic representativeness of our results. The population studied was similar to the US population in many aspects and the study center captures over 90% of Davidson County, TN infant hospitalizations. Infection rates in infants who did not present for treatment are unknown. A portion of infants presenting with illness did not have a study virus detected. It is possible that these were false-negative specimens, though our assays are sensitive and specific. These infants may have had low levels of virus shedding, had a non-viral illness or been infected with a virus not tested. Any additional evaluation performed on a study virus-negative patient was at the discretion of the clinical physician providing care.

In conclusion, we found that the most common causes for infants seeking care in unscheduled respiratory medical visits are two viruses for which we do not have treatment: for hospitalized infants, RSV, and for outpatient visits, HRV. Understanding host susceptibility and immune response to these viruses, as well as targeting the prevention of infection with these viruses in infancy may have even broader implications than focusing only on their role in acute infant respiratory disease morbidity.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the families enrolled in the Tennessee Children’s Respiratory Initiative.

Funding declaration: This work was supported by KL2 RR24977-03 (EKM), Thrasher New Investigator Award (EKM), Thrasher Research Fund Clinical Research Grant (TVH), NIH mid-career investigator award K24 AI 077930 (TVH), UL1 RR024975 (Vanderbilt CTSA), NIH K01 AI070808 mentored clinical science award (KNC), and NIH AI085062 (JVW). EKM is supported by NIH K23 AI091691-02 and March of Dimes Basil O’Conner Award. TVH is supported by NIH U19 AI 095227, R01 HS018454, R01 HS019669 and NIH K12 ES 015855. JVW serves on the Scientific Advisory Board for Quidel. TVH has received grant support from MedImmune. EKM has received grant support from MedImmune.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Supplemental Digital Content Legend

Conflict of interest statement: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Shay DK, Holman RC, Newman RD, Liu LL, Stout JW, Anderson LJ. Bronchiolitis-associated hospitalizations among US children, 1980–1996. Jama. 1999;282:1440–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.15.1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carroll KN, Gebretsadik T, Minton P, et al. Influence of maternal asthma on the cause and severity of infant acute respiratory tract infections. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129:1236–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.01.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Camara AA, Silva JM, Ferriani VP, et al. Risk factors for wheezing in a subtropical environment: role of respiratory viruses and allergen sensitization. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113:551–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2003.11.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller EK, Lu X, Erdman DD, et al. Rhinovirus-associated hospitalizations in young children. J Infect Dis. 2007;195:773–81. doi: 10.1086/511821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Singh AM, Moore PE, Gern JE, Lemanske RF, Jr, Hartert TV. Bronchiolitis to asthma: a review and call for studies of gene-virus interactions in asthma causation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:108–19. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200603-435PP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheuk DK, Tang IW, Chan KH, Woo PC, Peiris MJ, Chiu SS. Rhinovirus infection in hospitalized children in Hong Kong: a prospective study. The Pediatric infectious disease journal. 2007;26:995–1000. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181586b63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miller EK, Williams JV, Gebretsadik T, et al. Host and viral factors associated with severity of human rhinovirus-associated infant respiratory tract illness. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:883–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.11.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sigurs N, Bjarnason R, Sigurbergsson F, Kjellman B. Respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis in infancy is an important risk factor for asthma and allergy at age 7. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:1501–7. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.5.9906076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jackson DJ, Gangnon RE, Evans MD, et al. Wheezing rhinovirus illnesses in early life predict asthma development in high-risk children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178:667–72. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200802-309OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lemanske RF, Jr, Jackson DJ, Gangnon RE, et al. Rhinovirus illnesses during infancy predict subsequent childhood wheezing. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2005;116:571–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu P, Dupont WD, Griffin MR, et al. Evidence of a causal role of winter virus infection during infancy in early childhood asthma. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2008;178:1123–9. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200804-579OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hartert TV, Carroll K, Gebretsadik T, Woodward K, Minton P. Respirology. Carlton, Vic.: The Tennessee Children’s Respiratory Initiative: Objectives, design and recruitment results of a prospective cohort study investigating infant viral respiratory illness and the development of asthma and allergic diseases. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goebel J, Estrada B, Quinonez J, Nagji N, Sanford D, Boerth RC. Prednisolone plus albuterol versus albuterol alone in mild to moderate bronchiolitis. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2000;39:213–20. doi: 10.1177/000992280003900404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tal A, Bavilski C, Yohai D, Bearman JE, Gorodischer R, Moses SW. Dexamethasone and salbutamol in the treatment of acute wheezing in infants. Pediatrics. 1983;71:13–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lu X, Holloway B, Dare RK, et al. Real-time reverse transcription-PCR assay for comprehensive detection of human rhinoviruses. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:533–9. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01739-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Talbot HK, Shepherd BE, Crowe JE, Jr, et al. The pediatric burden of human coronaviruses evaluated for twenty years. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2009;28:682–7. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31819d0d27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ali SA, Gern JE, Hartert TV, et al. Real-world comparison of two molecular methods for detection of respiratory viruses. Virology journal. 2011;8:332. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-8-332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Griffin MR, Monto AS, Belongia EA, et al. Effectiveness of non-adjuvanted pandemic influenza A vaccines for preventing pandemic influenza acute respiratory illness visits in 4 U.S. communities. PloS one. 2011;6:e23085. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klemenc J, Asad Ali S, Johnson M, et al. Real-time reverse transcriptase PCR assay for improved detection of human metapneumovirus. J Clin Virol. 2012;54:371–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2012.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Calvo C, Pozo F, Garcia-Garcia M, et al. Detection of new respiratory viruses in hospitalized infants with bronchiolitis: a three-year prospective study. Acta Paediatr. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2010.01714.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miron D, Srugo I, Kra-Oz Z, et al. Sole pathogen in acute bronchiolitis: is there a role for other organisms apart from respiratory syncytial virus? The Pediatric infectious disease journal. 29:e7–e10. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181c2a212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Midulla F, Scagnolari C, Bonci E, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus, human bocavirus and rhinovirus bronchiolitis in infants. Arch Dis Child. 95:35–41. doi: 10.1136/adc.2008.153361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kusel MM, de Klerk NH, Holt PG, Kebadze T, Johnston SL, Sly PD. Role of respiratory viruses in acute upper and lower respiratory tract illness in the first year of life: a birth cohort study. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006;25:680–6. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000226912.88900.a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weinberg GA, Hall CB, Iwane MK, et al. Parainfluenza virus infection of young children: estimates of the population-based burden of hospitalization. The Journal of pediatrics. 2009;154:694–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Williams JV, Edwards KM, Weinberg GA, et al. Population-based incidence of human metapneumovirus infection among hospitalized children. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2010;201:1890–8. doi: 10.1086/652782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Korppi M, Kotaniemi-Syrjanen A, Waris M, Vainionpaa R, Reijonen TM. Rhinovirus-associated wheezing in infancy: comparison with respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2004;23:995–9. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000143642.72480.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martin ET, Kuypers J, Wald A, Englund JA. Multiple versus single virus respiratory infections: viral load and clinical disease severity in hospitalized children. Influenza and other respiratory viruses. 2012;6:71–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-2659.2011.00265.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.