Abstract

Introduction

The rising atmospheric CO2 level is continuously driving the dissolution of more CO2 into the oceans, and some emission scenarios project that the surface waters may reach 1000 μatm by the end of the century. It is not known if fish can detect moderately elevated CO2 levels, and if they avoid areas with high CO2. If so, avoidance behaviour to water with high CO2 could affect movement patterns and migrations of fish in the future. It is also being increasingly recognized that fish behaviour can be altered by exposure to CO2. Therefore this study investigated how long-term exposure to elevated pCO2 affects predator avoidance and CO2 avoidance in juvenile Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua). The fish were exposed to control water or CO2-enriched water (1000 μatm) for six weeks before being subjected to tests of behaviour.

Results

Despite long term exposure to elevated pCO2 the cod still strongly avoided the smell of a predator. These data are surprising because several coral reef fish have demonstrated reversal of olfactory responses after CO2 exposure, turning avoidance of predator cues into preference for predator cues. Fish from both treatment groups also demonstrated strong avoidance of CO2 when presented with the choice of control or CO2-acidified water, indicating that habituation to the CO2 sensory stimuli is negligible.

Conclusions

As Atlantic cod maintained normal behavioural responses to olfactory cues, they may be tolerant to CO2-induced behavioural changes. The results also suggest that despite the long-term exposure to CO2-acidified water, the fish still preferred the control water over CO2-acidified water. Therefore, in the future, fish may alter their movements and migrations in search of waters with a lower CO2 content.

Keywords: Carbon dioxide, Preference, Teleost, Ocean acidification, Oxygen minimum zone, CO2 maximum zone, Olfaction, Gadus morhua, GABA, Habituation

Introduction

Human activities are causing the release of CO2 into the atmosphere at increasing rates [1], resulting in a higher oceanic surface partial pressure for CO2 (pCO2) and a decrease in the pH in a process termed ocean acidification. Currently (may 2013), the levels have reached 400 ppm [2] and could reach 1000 ppm by the year 2100 (the fossil fuel intensive IPCC A1F1 emission scenario [1]), which will result in ~1000 μatm CO2 in the surface water [3].

A growing number of reports suggest that the behaviour of coral reef fishes may be highly affected by ocean acidification (see review by Briffa et al. [4]). The behavioural effects appeared at CO2 levels predicted by some emission scenarios (700–1200 μatm). A switch from repulsion to attraction to the scent of predators has been observed in several coral reef fish species after CO2 exposure. Damselfish larvae became attracted to the smell of predators at 700 μatm, and the larvae completely lost the ability to sense predators at 850 μatm [5]. A similar effect was observed in juvenile coral trout; when the fish were reared in 965 μatm CO2, they spent 90% of their time in the predator odour [6]. While the reversing effect of CO2-exposure on predator avoidance appears to be common in coral reef fish, it is still unknown if this is ubiquitous in teleosts from other parts of the world.

In order to optimize factors such as temperature, light, food availability and predator density [7], fish navigate through heterogeneous marine environments using many cues [8]. Teleosts employ external chemosensory receptors [2,9], possibly neuroepithelial cells located on the gills [1,10], to detect the ambient CO2 concentration. The physiological responses to acute exposure to elevated CO2 have been reasonably well described, and include bradycardia, hypertension and hyperventilation [3,11-13]. However, how fish behaviour, distribution and migration might be affected by a heterogeneous CO2 environment has received less attention [4,14]. It is known that teleosts avoid water with very high pCO2[5,15], and freshwater Arctic charr (Salvelinus alpinus) demonstrated attraction to low concentrations of CO2 but avoided higher concentrations of CO2 in a gradient tank [6,16].

How marine fish behave when presented with the choice of the relatively small concentration gradient of present-day pCO2 and a future scenario pCO2 is unknown. It is also unknown whether and how long-term exposure and acclimation to elevated CO2 levels will influence behavioural choices [7,14,17]. The issue of CO2 avoidance behaviour in fish has been highlighted as a concern that experimental biologists should investigate, in a review of possible effects of ocean acidification on fish [8,14]. If marine fish navigate using small differences in pCO2, then the increasing pCO2 due to anthropogenic disturbance could potentially affect the movement patterns and migrations of fish in the future ocean. For example, areas with heavy macrophyte growth can already reach high CO2 levels during the night [18]. With an increased baseline CO2 level from ocean acidification, the nightly increase in pCO2 in the local microclimate of macrophyte beds could become irritant to some fishes and lead to avoidance of sheltered areas [18].

We investigated whether the ecologically and economically important teleost Atlantic cod actively discriminate between control CO2 and elevated CO2 levels (1000 μatm), and if this behaviour is modulated by long-term exposure to CO2. Furthermore, we tested whether exposure to CO2 cause cod to lose the ability to avoid olfactory cues from predators.

Results

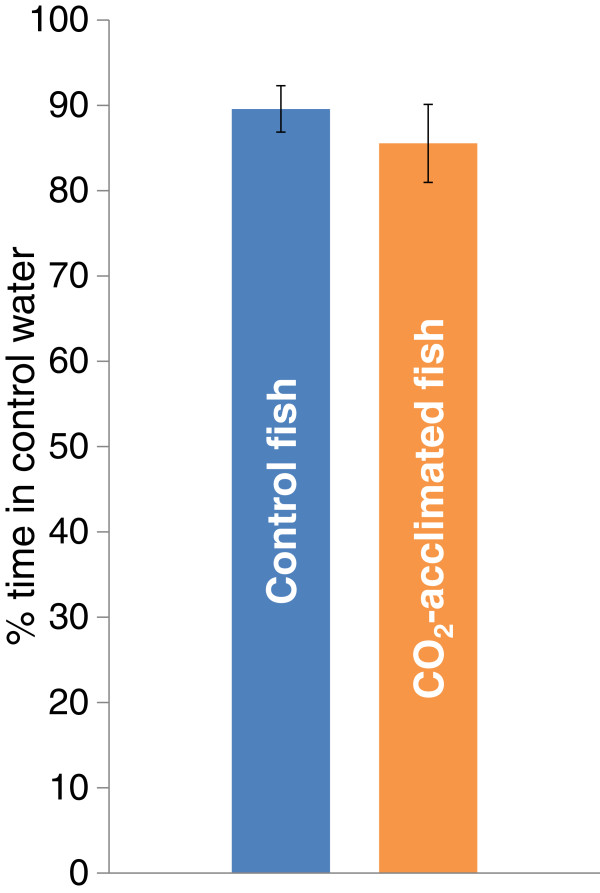

The fish from the control group actively avoided CO2-enriched water (p < 0.0001). The CO2-exposed fish demonstrated equally strong avoidance behaviour to CO2 (p < 0.0001). There was no significant difference between the control fish and CO2-exposed fish in the strength of avoidance behaviour (p = 0.482, ncontrol = 19, nCO2 = 13) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

CO2 avoidance in Atlantic cod after long-term exposure to control water or high pCO2 water. Mean time (%) that juvenile Gadus morhua spent in the control water (550 μatm CO2) when presented with the choice of control water or high pCO2 water (1170 μatm CO2); ncontrol = 19 and nCO2 = 12. Fish from both acclimation groups were tested: the control fish and the long-term CO2-exposed fish. Both treatment groups displayed equally strong avoidance (p = 0.0001). The data represent the mean ± SEM.

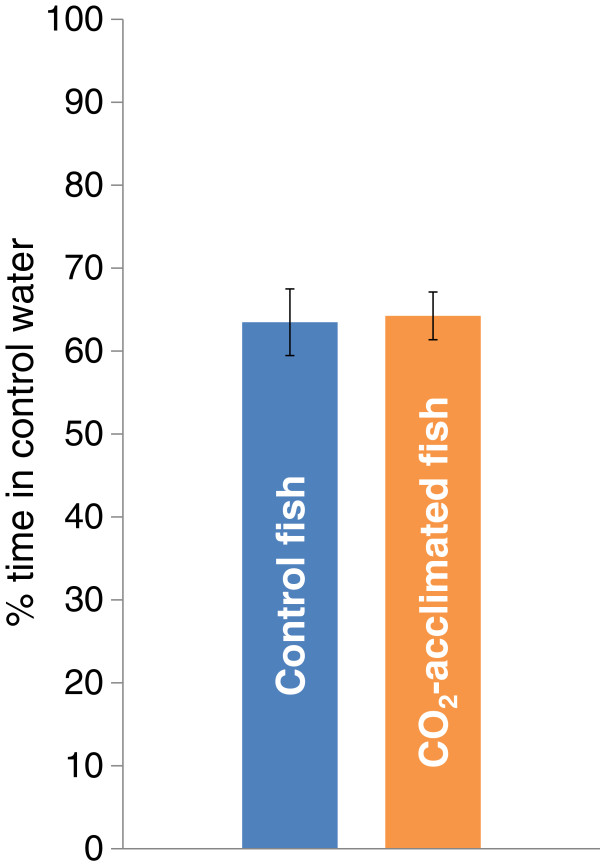

In the predator avoidance test (Figure 2), both the control fish and the CO2-exposed fish avoided the water coming from the header tank that contained a potential predator (pControl fish < 0.0001 and pCO2 fish <0.0001). There was no significant difference in the strength of the avoidance behaviour between treatments (nested ANOVA; p = 0.481, ncontrol = 18, nCO2 = 13).

Figure 2.

Predator cue avoidance in Atlantic cod after long-term exposure to control water or high pCO2 water. Mean time (%) that juvenile Gadus morhua spent in the control water, when presented with the choice of control water or water with predator odor; ncontrol = 19 and nCO2 = 12. Both treatment groups displayed equally strong avoidance (p = 0.0001). The data represent the mean ± SEM.

Discussion

Increased CO2 concentrations in the water can elicit sensory responses in fish [10,13,19] as well as physiological responses [1,12]. However, it has been unclear whether near-future CO2-levels can provoke avoidance behaviour in marine fish. In this study, we demonstrated that juvenile Atlantic cod strongly avoided water containing increased pCO2 (1000 μatm) in favour of water containing the control CO2 concentration (500 μatm). The fish spent 90% of their time in the control water, indicating that elevated pCO2 is highly undesirable for young cod.

Surprisingly, the long-term acclimated cod showed the same level of avoidance behaviour as the control fish. This finding suggests that despite the possible acclimation and habituation processes, the cod still considered the high pCO2 water as suboptimal and avoided it. Repeated exposure to a sensory stimulus can lead to habituation, and the response to subsequent exposures to the same stimuli has a decreased magnitude [20]. The fish were under constant exposure to high pCO2 for over one month, which could theoretically have induced habituation or a shift in the baseline of what is categorized as “normal” for the fish, which would have led to a lower level of avoidance of or possibly even a preference for high CO2. Because habituation was not detected, it is possible that the habituation of sensory systems to high CO2 is a very slow or non-existent process in fish.

It has been suggested that any CO2 avoidance behaviour in fish could affect their distribution, migration patterns and, therefore, the marine ecosystem structure [6,14]. Theoretically, fish could avoid areas of high pCO2 and actively seek out lower pCO2 waters over both long and short timescales. Daily migrations could be affected in areas with high biomass because the pCO2 could already be high because of net respiration during darkness [18,21,22], and combined with ocean acidification, this could drive the CO2 levels into the avoidance range for cod.

Pelagic fish normally avoid the mesopelagic oxygen minimum zone, and hypoxia has been suggested as the repellent [7,23,24]. However, these hypoxic zones are also associated with high pCO2[8,25,26], which suggests that the avoidance behaviour against oxygen minimum zones observed in nature [9,25] could be associated with high pCO2 as well as hypoxia. Because of the close association of hypoxia with hypercapnia in nature, fish may also use hypercapnia as a proxy for harmful oxygen levels despite being tolerant to the CO2 itself. While it is too early to draw firm conclusions regarding the ecological relevance of the CO2 avoidance behaviour in marine fish, the subject deserves more attention.

Because CO2 exposure reverses the preferences to olfactory cues in several coral reef teleost species, as well as affects the behaviour of temperate sticklebacks [27] and gobies [28], we hypothesized that cod would exhibit a reversal of avoidance behaviour. However, cod exposed to CO2 for one month avoided both CO2 and the predator odour with the same magnitude as the control water-exposed fish, suggesting that the reversal of olfactory preference observed in the tropical reef fish [4] is not ubiquitous among teleost species. Therefore, it is possible that cod is a species that does not demonstrate dramatic behavioural changes following CO2 exposure, although this has to be investigated using several independent tests of behaviour. This is corroborated by results from larval Atlantic cod where the larvae maintained normal behaviour despite long term exposure to very high pCO2 (4200 μatm) [29]. Neural tolerance to high pCO2 in Atlantic cod may be an adapted trait as some populations have been shown to enter hypoxic deep water (≤ 20% O2 saturation) to feed [30]. The mechanism for such tolerance is unknown but could involve modulation to the ion permeability of certain neural ion channels, for example the GABAA receptor Cl- channel [31]. As hypoxic deep water is commonly associated with hypercapnia (500–2500 μatm CO2 in the Baltic sea [26]), it should be beneficial for cod to maintain normal behaviour despite the high pCO2 in the deep water.

Conclusions

We have shown that Atlantic cod strongly avoided water with elevated CO2 levels when given the choice, indicating that cod may navigate using CO2 as a cue in a heterogeneous pCO2 landscape. The avoidance of high CO2 was maintained despite over one month of exposure and acclimation to elevated CO2 levels, demonstrating that habituation of the CO2 sensory system is minimal. Ocean acidification may therefore alter movement patterns and migrations of fish in the future.

Materials and methods

Fish rearing and treatment

The ethical animal experimentation committee (Gothenburg, Sweden, ethical permits Jutfelt 100–2010 and Jutfelt 151–2011) approved the fish handling, exposure and testing.

In total, 56 juvenile Atlantic cod (G. morhua) were collected using cages and seine nets close to Sauna Island at the Kristineberg Marine Station, Sweden (lat. 58.2497, long. 11.4455). The fish were measured and weighed at the start and end of the experiment, and randomly distributed in equal numbers to the four tanks. The fish were fed daily with shrimp (Pandalus sp.). All mortalities were recorded. At the start of the exposure period the fish had a mean weight of 8.3 g ± 5.0 SD (6.6 g ± 3.7 SD, n = 28, for control fish and 9.9 g ± 5.6 SD, n = 28, for the high pCO2 fish); and a mean length of 9.4 cm ± 1.4 SD (9.0 cm ± 1.2 SD for control fish and 9.8 cm ± 1.5 SD for high pCO2 fish). At termination of the experiment the control fish had a mean weight of 12.0 g ± 9.3 SD and the high pCO2 fish 19.6 g ± 11.8 SD, and the lengths were 10.6 ± 2.2 SD for control fish and 12.5 ± 2.2 SD for high pCO2 fish. The total mortality in the CO2 tanks was 56%, of which 50% was due to cannibalism and the rest due to unknown causes. The mortality in the control tanks was 28%, of which 29% was due to cannibalism.

Round fiberglass 100 L tanks (4 in total) with flow-through water (taken from 30 meters depth) were used, and each was equipped with a separate 200 L aerated header tank. The fish were exposed to either control water (532 μatm ± 43 SD, which is the normal pCO2 for deep water at this location) or water containing elevated CO2 (1014 μatm ±76 SD, representing a business as usual emission scenario [1]). The exposure duration was 41 days, representing a sufficient time for growth in the new environment as well as possible acclimation. The tanks were covered with clear polycarbonate sheaths to prevent gas exchange with the atmosphere. The in situ pCO2 levels in the fish tanks was measured daily throughout the experiment using an infrared CO2 probe (Vaisala GM70, equipped with an aspiration pump, Vaisala, Finland) connected to a thin-walled silicone tubing loop with trapped circulating air in equilibrium with dissolved water gases, as described previously [6,27,32]. The pCO2 in the header tanks was maintained using pH-stat computers equipped with pH probes (Aquamedic, Germany), and solenoid valves were used to control the administration of pure CO2 (Aga, Sweden). The temperature was recorded continuously, and the mean temperature was 14.4°C ± 0.44 (SD). The alkalinity of the deep water from the Gullmar fjord was measured weekly. The oxygen saturation of the fish tanks was measured on several occasions and was consistently greater than 90% in all tanks. The water carbonate chemistry was calculated using pCO2, salinity, temperature, and alkalinity in CO2calc (Hansen, USGS, USA) and the results are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Water chemistry for the treatments control and elevated CO 2

| Parameter | Control | Elevated CO 2 |

|---|---|---|

| pCO2 (μatm) |

532.4 ± 42.7 |

1013.5 ± 76.0 |

| Alkalinity (TA) |

2350 ± 37.1 |

2363 ± 53.7 |

| Salinity (PSU) |

33.1 ± 0.8 |

33.1 ± 0.8 |

| Temp (°C) |

14.4 ± 0.5 |

14.4 ± 0.5 |

| pHtot (calc.) |

7.95 ± 0.04 |

7.69 ± 0.03 |

| Ωaragonite (calc.) |

2.10 ± 0.21 |

1.22 ± 0.08 |

| Ωcalcite (calc.) | 3.29 ± 0.33 | 1.90 ± 0.13 |

Temperature, salinity, pCO2 and alkalinity (AT) are measured data; pHtot, Ωaragonite and Ωcalcite are calculated data using CO2calc (USGS, USA). Data is presented as means ± SD.

During the exposure period, starting from day 35 and continuing to day 41, the fish were subjected the behavioural tests. Fish from both groups were tested on the same days, ensuring identical exposure and acclimation times for both treatment groups. The fish were always tested in the treatment water pCO2, temperature and light conditions they were accustomed.

Flume choice test

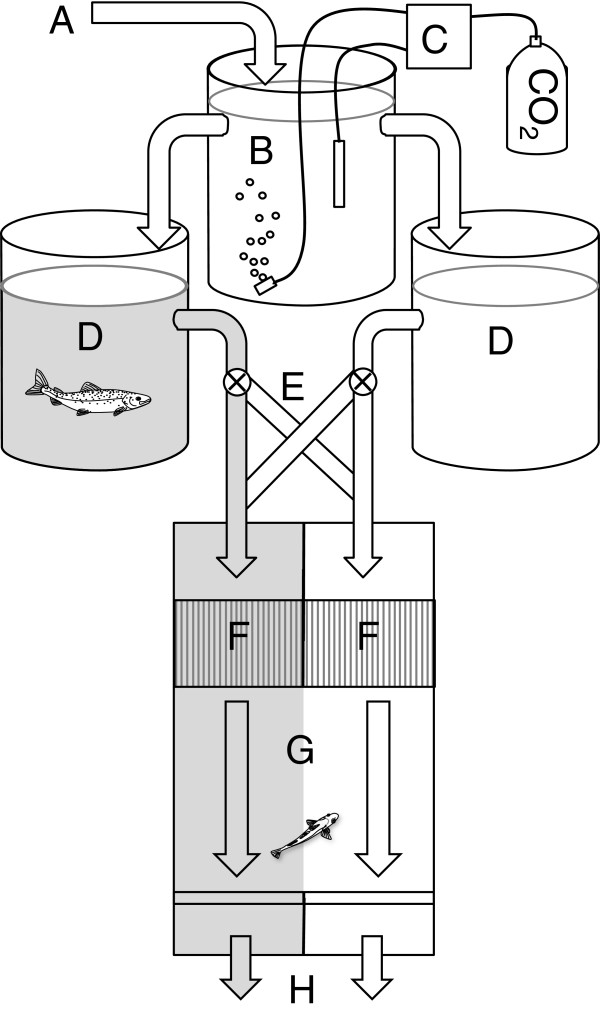

The olfactory flume choice tests and the statistical analyses were performed according to the method described in Gerlach et al. 2007 [33], with some modification to sizes and times described below. A two-choice flume channel (Choice Tank, Loligo Systems, Denmark) containing a 32×40 cm choice arena with a water depth of 15 cm was used to investigate the ability of the cod to detect chemical and olfactory cues (Figure 3). Single fish were placed in the choice arena where the fish could swim freely between two water masses. The two water masses were continuously supplied, in a flow through manner, by two 200 L header tanks, into which cues could be introduced. The two water masses passed through the choice arena with laminar flow at a speed of 1 cm/s, with less than 1 cm of mixed turbulent water between the two laminar flows. The fish could therefore always be determined to be in either of the water masses. The laminar flow of the two parallel water flows was verified by adding dye to one header tank during the method optimization procedure. The pipes connecting the header tanks with the flume were fitted with a crossover switch, which allowed quick change of sides of the olfactory cue without the fish seeing or otherwise noticing the experimenter. A video camera (Dragonfly II, Pointgrey, Richmond, Canada) positioned above the flume was used to record each trial. Individual fish were placed in the flume (marked “G” in Figure 3 and filmed for 20 minutes before the flows were switched, and the olfactory cue switched side of the flume within one minute. After the switch, the flow was maintained for 12 minutes. The time before the switch was longer because the fish needed time to calm down after handling before responding to olfactory cues (according to our method development for this species and life stage). Analysis of fish positions was performed during the last 5 minutes prior to the switch and the last 5 minutes after the switch. The position of the fish was recorded every five seconds. The preferred side for each fish was calculated as the side that the fish spent more than 50% of the time in during each 5-minute period. Each fish was then used as its own control in the non-parametric statistical test; the preferred side before the switch was compared to the preferred side after the switch, see the statistics section below for details. A lack of preference (50% of the time in each water mass) would be expected if the fish did not prefer one olfactory cue, or if the fish were unable to detect the cue.

Figure 3.

Choice flume chamber experimental setup with pCO2 control and predator cues on one side. Choice flume test. Schematic drawing of the choice flume test used for predator avoidance measurements in juvenile cod. The shaded areas represent water with predator odour. The letters represent the following: A. Flow-through water inlet. B. Main header tank. C. pH-stat system with pH probe and solenoid valve controlling the administration of CO2 into the main header tank. D. Header tanks for the two sides of the choice flume, with one side containing a predatory fish. E. Cross-over piping for changing sides of the cue. F. Honeycomb plastic for laminar flow. G. Choice arena for the tested fish. The two waters were kept separate by laminar flow, and movements only caused minimal short lasting mixing. H. Flume drains.

Predator avoidance

Predator avoidance was tested at 40 and 41 days of exposure. The flume choice test described above was used to investigate the ability of the cod to detect a predator cue (Figure 3) [34]. Brown trout (Salmo trutta) is a piscivore that inhabits the same biotope as juvenile cod [35]; therefore, this fish is a likely predator of small cod. A main header tank (200 L) (marked “B” in Figure 3) with aeration and pCO2 control was used to supply the two downstream header tanks (200 L) (marked “D” in Figure 3), making it possible to use the pCO2 that the fish were acclimated to on both sides of the flume simultaneously, so that the CO2 concentration did not affect the choice of water mass. The two header tanks with flow-through water (one control tank and one tank containing a live wild-caught 500 g trout) supplied water to the two sides of the flume at a flow rate of 17 L/minute each.

CO2 avoidance

CO2 avoidance was tested at 35 to 37 days of exposure. The two-choice flume channel used to investigate the ability of cod to detect elevated CO2 levels (1000 μatm) was similar to the setup for predator avoidance but without header tank “B” Figure 3. Two header tanks with flow-through water (tanks “D” in Figure 3 one control tank (500 μatm) and one tank with an elevated CO2 concentration (1000 μatm)) supplied the two sides of the flume at a flow rate of 17 L/minute each. The same protocol for video analysis as in the predator avoidance test was used.

Data analysis

Nested ANOVAs (tank nested within treatment) in SPSS were used to investigate treatment (the long-term exposure to control water or elevated pCO2) and tank effects on CO2 avoidance and predator avoidance. The ANOVAs used the % of time spent in control water as the variable. No tank effects were detected for any parameter (at the p < 0.1 level). The non-parametric Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to detect possible CO2 and predator avoidance within treatments, in which the position (in control water mass or in water mass with olfactory cues) of the individual fish was compared before and after the switching of the side with odour or CO2. This method of statistically testing preference and avoidance is described in Gerlach et al. 2007. The data are presented as the mean ± SEM, unless otherwise noted.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

FJ and MH designed and conducted the experiments. MH performed the statistical analysis. FJ wrote the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

FJ and MH address: Department Biological and Environmental Sciences, University of Gothenburg, Medicinaregatan 18, 41390 Gothenburg, Sweden. Secondary address: The Sven Lovin Centre Kristineberg, Kristineberg 566, SE-451 78 Fiskebäckskil, Sweden.

Contributor Information

Fredrik Jutfelt, Email: fredrik.jutfelt@bioenv.gu.se.

Maria Hedgärde, Email: maria.hedgarde@hotmail.com.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kim Hellgren, Leon Green, Bengt Lundve, Marian Hu and Niklas Andersson for excellent animal handling. The Swedish Research Council Formas, grant Jutfelt 2009–596, funded this study.

References

- Solomon S, Qin D, Manning M, Alley RB, Berntsen T, Wratt D. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge, UK and NY, USA: Cambridge University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Earth System Research Laboratory. http://www.esrl.noaa.gov/news/2013/CO2400.html.

- Doney SC, Ruckelshaus M. Emmett Duffy J, Barry JP, Chan F, English CA, Galindo HM, Grebmeier JM, Hollowed AB, Knowlton N, Polovina J, Rabalais NN, Sydeman WJ, Talley LD: Climate Change Impacts on Marine Ecosystems. Annu Rev Marine Sci. 2012;10:11–37. doi: 10.1146/annurev-marine-041911-111611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briffa M, La Haye De K, Munday PL. High CO2 and marine animal behaviour: potential mechanisms and ecological consequences. Mari Pollut Bull. 2012;10:1519–1528. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2012.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munday PL, Dixson DL, McCormick MI, Meekan M, Ferrari MCO, Chivers DP. Replenishment of fish populations is threatened by ocean acidification. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;10:12930–12934. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004519107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munday PL, Pratchett MS, Dixson DL, Donelson JM, Endo GGK. et al. Elevated CO2 affects the behavior of an ecologically and economically important coral reef fish. Mar Biol. 2012;10:2137–2144. Available: http://www.springerlink.com/index/10.1007/s00227-012-2111-6. [Google Scholar]

- Righton DA, Andersen KH, Neat F, Thorsteinsson V, Steingrund P, Svedäng H, Michalsen K, Hinrichsen HH, Bendall V, Neuenfeldt S, Wright P, Jonsson P, Huse G, van der Kooij J, Mosegaard H, Hüssy K, Metcalfe J. Thermal niche of Atlantic cod Gadus morhua: limits, tolerance and optima. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 2010;10:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- SMELL, TASTE, AND CHEMICAL SENSING | Chemoreception (Smell and Taste) An Introduction. In: Farrell AP, editor. Encyclopedia of Fish Physiology. San Diego: Academic Press; 2011. pp. 183–186. ISBN 9780080923239, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-374553-8.00021-6. Keywords: Gustation; Olfaction; Smell; Taste. [Google Scholar]

- Perry SF, Gilmour KM. Sensing and transfer of respiratory gases at the fish gill. J Exp Zool. 2002;10:249–263. doi: 10.1002/jez.10129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin Z, Lewis JE, Perry SF. Zebrafish (Danio rerio) gill neuroepithelial cells are sensitive chemoreceptors for environmental CO2. J Physiol. 2010;10:861–872. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.184739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara TJ. The diversity of chemical stimulation in fish olfaction and gustation. Rev Fish Biol Fisheries. 1994;10:1–35. doi: 10.1007/BF00043259. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Perry SF, Abdallah S. Mechanisms and consequences of carbon dioxide sensing in fish. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2012;10:309–315. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2012.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshii K, Kashiwayanagi M, Kurihara K, Kobatake Y. High sensitivity of the eel palatine receptors to carbon dioxide. Comp Biochem Physiol A Comp Physiol. 1980;10:327–330. doi: 10.1016/0300-9629(80)90170-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ishimatsu A. Physiological effects on fishes in a high-CO 2world. J Geophys Res. 2005;10:C09S09. [Google Scholar]

- Clingerman J, Bebak J, Mazik PM, Summerfelt ST. Use of avoidance response by rainbow trout to carbon dioxide for fish self-transfer between tanks. Aquacultural Eng. 2007;10:234–251. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaeng.2007.07.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jones KA, Hara TJ, Scherer E. Locomotor response by Arctic char (Salvelinus alpinus) to gradients of H+ and CO2. Physiological zoology. 1985;10:413–420. [Google Scholar]

- Ishimatsu A, Hayashi M, Kikkawa T. Fishes in high-CO2, acidified oceans. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 2008;10:295–302. [Google Scholar]

- Saderne V, Fietzek P, Herman PMJ. Extreme variations of pCO2 and pH in a macrophyte meadow of the baltic sea in summer: evidence of the effect of photosynthesis and local upwelling. PLoS One. 2013;10:e62689. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara TJ. Olfaction and gustation in fish: an overview. Acta Physiol Scand. 1994;10:207–217. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1994.tb09800.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maximino C, de Brito TM, da Silva Batista AW, Herculano AM, Morato S, Gouveia A Jr. Measuring anxiety in zebrafish: a critical review. Behav Brain Res. 2010;10:157–171. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2010.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cripps IL, Munday PL, McCormick MI. Ocean acidification affects prey detection by a predatory reef fish. PLoS One. 2011;10:e22736. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann GE, Barry JP, Edmunds PJ, Gates RD, Hutchins DA, Klinger T, Sewell MA. The effect of ocean acidification on calcifying organisms in marine ecosystems: an organism-to-ecosystem perspective. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst. 2010;10:127–147. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.110308.120227. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stramma L, Prince ED, Schmidtko S, Luo J, Hoolihan JP, Visbeck M, Wallace DWR, Brandt P, Körtzinger A. Expansion of oxygen minimum zones may reduce available habitat for tropical pelagic fishes. Nat Climate Change. 2011;10:33–37. doi: 10.1038/nclimate1304. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seibel BA. Critical oxygen levels and metabolic suppression in oceanic oxygen minimum zones. J Exp Biol. 2010;10:326–336. doi: 10.1242/jeb.049171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulmier A, Ruiz-Pino D, Garçon V. CO2 maximum in the oxygen minimum zone (OMZ) Biogeosciences. 2011;10:239–252. doi: 10.5194/bg-8-239-2011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Melzner F, Thomsen J, Koeve W, Oschlies A, Gutowska MA. et al. Future ocean acidification will be amplified by hypoxia in coastal habitats. Mar Biol. 2012;10:1875–1888. doi:10.1007/s00227-012-1954-1. [Google Scholar]

- Jutfelt F, Bresolin de Souza K, Vuylsteke A, Sturve J. Behavioural disturbances in a temperate fish exposed to sustained high-CO2 levels. PLoS ONE. 2013;10:e65825. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065825. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0065825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsgren E, Dupont S, Jutfelt F, Amundsen T. Elevated CO2 affects embryonic development and larval phototaxis in a temperate marine fish. Ecol Evol. 2013;10:3637–3646. doi: 10.1002/ece3.709. doi:10.1002/ece3.709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maneja RH, Frommel AY, Browman HI, Clemmesen C, Geffen AJ. et al. The swimming kinematics of larval Atlantic cod, Gadus morhua L., are resilient to elevated seawater pCO2. Mar Biol. 2012;10:1963–1972. doi:10.1007/s00227-012-2054-y. [Google Scholar]

- Neuenfeldt S, Andersen KH, Hinrichsen HH. Some Atlantic cod Gadus morhuain the Baltic Sea visit hypoxic water briefly but often. J Fish Biol. 2009;10:290–294. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8649.2009.02281.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson GE, Dixson DL, Domenici P, McCormick MI, Sørensen C, Watson S-A, Munday PL. Near-future carbon dioxide levels alter fish behaviour by interfering with neurotransmitter function. Nat Climate Change. 2012;10:201–204. doi: 10.1038/nclimate1352. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hari P, Pumpanen J, Huotari J, Kolari P, Grace J, Vesala T, Ojala A. High-frequency measurements of productivity of planktonic algae using rugged nondispersive infrared carbon dioxide probes. Limnol Oceanogr Methods. 2008;10:347–354. [Google Scholar]

- Gerlach G, Atema J, Kingsford MJ, Black KP, Miller-Sims V. Smelling home can prevent dispersal of reef fish larvae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;10:858–863. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606777104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbert NA, Skjæraasen JE, Nilsen T, Salvanes AGV, Steffensen JF. The hypoxia avoidance behaviour of juvenile Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua L.) depends on the provision and pressure level of an O2 refuge. Mar Biol. 2010;10:737–746. [Google Scholar]

- Wennhage H, Pihl L. Fish feeding guilds in shallow rocky and soft bottom areas on the Swedish west coast. J Fish Biol. 2002;10(sa):207–228. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8649.2002.tb01772.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]