Abstract

Purpose

Vigabatrin (γ-vinyl-GABA) is an antiepileptic drug successful in the management of infantile spasms. Photopic ERGs were tested in children followed longitudinally before and during vigabatrin treatment.

Methods

Subjects were 26 infants (age range 1.5–24 months, median 7.6 months) on vigabatrin treatment who had been tested on multiple visits (two to four visits; mean, three visits). Eighteen of these were assessed initially before starting vigabatrin therapy and eight were assessed within 1 week of initiation of the drug. ERGs were recorded at 6-month intervals. Standard ISCEV protocol with Burian-Allen bipolar contact-lens electrodes (standard flash 2.0 cd.s/m2) was used. Although ISCEV standards were followed, a higher flash intensity (set at 3.6 cd.s/m2) was chosen for single-flash cone assessment to provide a better definition of OPs. Photopic OPs were divided into categories of early OPs and late OP (OP4). Responses were compared with age corrected limits extrapolated from our lab control database.

Results

Results showed differential effects of vigabatrin on the summed early OP amplitudes versus the late OP (OP4) and cone b-wave amplitude. The early OPs showed significant decrease (p = 0.0005, repeated measures analysis of variance) after 6 months and remained decreased for the duration of treatment. There was no significant change seen in the late OP. The cone b-wave amplitude showed initial increase (p = 0.04) after 6 months, followed by a decrease after 18 months; a trend similar to that of the late OP.

Conclusion

Early photopic OPs were disrupted more than the late OP, suggesting relative deficit in the ON (depolarizing) retinal pathways.

Keywords: ERG, longitudinal, paediatric, vigabatrin

Introduction

Vigabatrin has been associated with several electrophysiological abnormalities. These abnormalities have primarily involved the cone system [1–4]. A recent publication [5] reported longitudinal changes in electroretinogram (ERG) cone responses of children on vigabatrin therapy; an initial increase was seen in the cone b-wave amplitude followed by subsequent reduction.

This paper describes further changes in the photopic ERG with time on vigabatrin treatment, in the same paediatric population, with primary emphasis being placed on the oscillatory potential (OP) amplitude.

OPs are small wavelets superimposed on the ascending limb of the b-wave [6, 7] Profile studies have provided evidence to suggest that the OPs originate in the inner plexiform layer [8–10]. OPs can be obtained under both dark-adapted (scotopic) and light-adapted (photopic) conditions. Photopic OPs are filtered out from the b-wave of the cone response while the scotopic OPs are filtered out from the b-wave of the mixed rod-cone response. The nomenclature for OP responses used in this paper are described by Lachapelle and Benoit 1994 [11] the early OPs representing OP2+OP3 and the late OP representing OP4.

The present study primarily investigates the quantitative changes in the photopic OP amplitudes of children followed longitudinally before and during vigabatrin treatment. As a secondary objective we report our latest findings of the cone b-wave amplitude and flicker responses. These data include data collected 15 months after completion of those reported in Westall et al. [5].

Methods

Twenty-six children on vigabatrin treatment, referred for ophthalmological, visual and electrophysiological assessment, were tested longitudinally; the duration between visits was approximately 6 months. Eighteen of these children were assessed initially before starting vigabatrin treatment and another eight were assessed soon after (within 1 week). The results from these visits constituted the baseline ERG response (age range 1–21 months, mean 9 months, median 7.5 months). Subjects were excluded from the study if they had a retinal dystrophy or a known family history of retinal dystrophy, any eye disease associated with abnormal ERG, previous intraocular surgery or systemic disease known to affect the retina. Visual acuity was assessed using preferential looking techniques, with Teller acuity cards (Vistech Consultants, Dayton, OH) or Cardiff Acuity test (Keeler, Windsor, UK) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Subject | Age start of vigabatrin (months) | Type of seizure | Other health problems | Other meds | Total cumulative dosage (g/kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 6 | Gen T/C | TS | Started carbamazepine | 37 g |

| 2* | 16 | IS | DD, strab, microencephaly | Nitrazepam, VGB d/c at 26 months started VPA | 29 g 29 g |

| 4 | 7 | IS | DD, nystag, strab, lissencephaly | Phenobarbital | 55 g |

| 5 | 5 | IS | Trisomy 21 | 53 g | |

| 6 | 7 | IS | TS | Phenobarbital | 79 g |

| 13 | 1.5 | Tonic | DD | Clobazam, phenobarbital | 38 g |

| 19 | 7 | IS | DD | 23 g | |

| 39 | 5 | IS | DD | Phenobarbital | 70 g |

| 43 | 6 | Seiz. | 49 g | ||

| 38 | 4 | IS | ACC, DD | Phenobarbital, Lamictal, Lozac, Cisapride | 100 g |

| 44 | 11 | IS | TS, DD | Phenobarbital | 28 g |

| 46 | 6 | IS | Mild DD | 79 g | |

| 55 | 26 | IS | 21 g | ||

| 49 | 13 | IS | NF-1, Optic glioma | 21 g | |

| 45 | 4 | IS | Lissencephaly | Phenobarbital | 72 g |

| 26 | 6 | IS | 40 g | ||

| 60 | 3 | Seiz. | Phenobarbital, Clobazam | 53 g | |

| 70 | 9 | IS | ACTH | 47 g | |

| 56 | 8 | IS | Topiramate | 27 g | |

| 71 | 13 | IS | DD, CVL | Phenobarbital, Clobazam | 23 g |

| 74 | 13 | IS | Phenobarbital, Clobazam | 27 g | |

| 63 | 10.5 | TS | 94 g | ||

| 101 | 21 | Seiz. | Trisomy 21 | Synthroid | |

| 75 | 85 | IS | 42 g | ||

| 77 | 8 | IS | SGS, DD | 42 g | |

| 57 | 13 | TS | 82 g |

TS – tuberous sclerosis; IS – infantile spasms; genT/C – generalized tonic/clonic seizures; T – tonic seizures; DW – Dandy Walker syndrome; ACC – Absence of corpus callosum; CVL – cortical visual loss; DD – developmental delay; NF-1 – Neurofibromatosis type 1; SGS – Schinzel-Giedion syndrome; MDF – mild dysmorphic features; enceph – encephalopathy; lissenceph – lissencephaly; microenceph – microencephaly; nystag – nystagmus; strab – strabismus; when other drugs were started after initation of therapy this is indicated.

Age start of vigabatrin = age of first ERG except subject 2 when ERG recorded 3 months before vigabatrin.

All testing was performed in the Visual Electrophysiology Unit at the Hospital for Sick Children. The research follows the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Parents of subjects gave signed consent for their participation in the study. The consent form acknowledged that research procedures were described, any questions answered and that harms and benefits of participating were fully explained. Approval for the study was obtained from the Research Ethics Board at the Hospital for Sick Children.

Most children were sedated with oral chloral hydrate (80 mg/kg of body weight; maximum single dose 1 g). For details of ERG measurement see Westall et al. [5]. Briefly, pupils were pharmacologically dilated with 1% cyclopentolate and 2.5% phenylephrine in children and with 0.5% cyclopentolate in infants less than 4 months. Each subject was dark-adapted for at least 30 min before recording began. Burian-Allen electrodes (Hansen Ophthalmic Development Laboratory, Iowa City, IA) of the appropriate size for the individual subject, were used to record ERGs. A Grass PS22 photic stimulator (Grass Instruments, Quincy, MA) and Ganzfeld stimulation (LKC Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD) controlled the light delivery. Neuroscan (Herndon, VA) manufactured the recording equipment and software used.

After dark-adapted responses were recorded, subjects were light-adapted to a 30-cd/m2 background for 10 min. Photopic single-flash cone responses (3.6 cds/m2), followed by 30-Hz flicker (2.0 cds/m2) responses were recorded in the presence of the same adapting background. In the current paper we report only on the photopic ERGs, although rod-cone responses have been shown for comparison. OP responses were analysed off-line. OPs were isolated from the cone response by digital-filtering (bandwidth, 100–300 Hz; roll off 12 dB/octave) and averaging the epochs. The amplitudes of OP2 and OP3 were summed to derive the OP2 + OP3 amplitude (termed early OPs).

After ERG testing, both direct and indirect ophthalmoscopy was performed by an ophthalmologist (RB) through pharmacologically dilated pupils on all patients.

Data analysis

Much of our data were collected from infants while ERG responses were still developing [12]. To avoid confounding effects of age expected developmental changes in longitudinal measures of ERGs, all data were expressed as relative units to age-expected responses. For amplitude data the log of the age expected amplitude was subtracted from the log of the individual response; negative values therefore represented reduction in ERG amplitude relative to expected value. For implicit time data, age expected implicit times were subtracted from individual patient values and therefore responses that were delayed relative to expected values were represented by positive values.

Two tailed paired t-tests were used to test for difference in ERG data between visit 1 (baseline) and visit 2 (6 months on vigabatrin) and to test for differences between baseline and the final visit (24 months on vigabatrin). Ten t-tests were carried out; therefore for significance the p value was required to be less than 0.005. Repeated measures for analysis of variance (ANOVA) were tested for change over time.

Descriptive statistics were used to illustrate changes in ERG responses over time. The visit classification depended on approximate duration of vigabat-rin treatment. The baseline visit was defined as the time at initiation of vigabatrin. Subsequent visits were approximately 6 months after baseline testing (range 4–8 months); at 12 months (range 10–14 months); at 18 months (range 16–20 months) and at 24 months (23–26 months).

Results

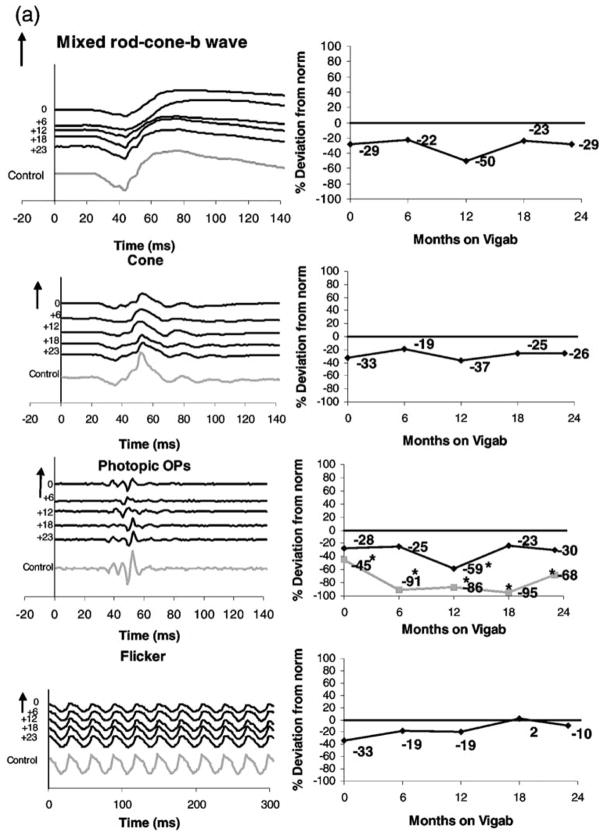

Representative data describing ERG cone system responses from two children on vigabatrin treatment are shown in Figure 1. Photopic ERGs: the cone isolated response, photopic oscillatory potentials and the 30-Hz flicker response are shown in the left column. Mixed rod-cone responses are shown for comparison.

Figure 1.

Sample ERG traces: (left column) and percent deviation from control (right column) From top to bottom: mixed rod cone responses, cone isolated responses, photopic oscillatory potentials (late OP, black line; early OPs, grey line) and the 30-Hz flicker. (a) Subject 49, a 6-month-old child before and at approximately 6-month intervals during vigabatrin treatment. The last waveform is from data recorded from a 34-month-old control (with normal vision). (b) Subject 6, a 6-month-old child had been on vigabatrin 7 days and at approximately 6-month intervals during vigabatrin treatment. Numbers at the left of the series of traces shows length of time on vigabatrin. Time is shown in milliseconds. Positive electrical signals are in the upward direction. Vertical arrows and numbers represent 100 μV. The flash intensity for the photopic single flash cone responses is 3.6 cds/m2 and the flicker flash intensity is 2.0 cds/m2. For the flicker response the stimulus flash is at time 0. For all other responses the stimulus flash is at 20 ms. *Abnormal amplitude levels.

Subject 49 was diagnosed with infantile spasms at seven months of age. She had a normal birth history but demonstrated some developmental delay. Her ERGs are shown in Figure 1a. Her first ERG was recorded at 13 months of age before initiation of vigabatrin treatment. At this time, the cone b-wave, late OP and flicker were slightly reduced when compared with control, but still within normal limits. The early OPs however, were abnormally reduced (45% reduction) compared with control. Her initial dose of vigabatrin was 1500 mg/day (147 mg/kg per day). After 6 months of vigabatrin treatment (19 months of age) ERG responses were within normal limits with the exception of the early OPs (91% reduction). For the next two visits, (+12, and 18 months) the dose of vigabatrin (mg/kg) decreased from 140 to 133 mg/kg. After 18 months on vigabatrin the cone and flicker responses, as well as OP4 were within normal limits (refer to Figure 1a for percent deviations). By the last visit, vigabatrin was being tapered and the dose was now 43 mg/kg per day. There was some improvement in the early OP responses from the previous visit (from 95 to 68% reduction) and the flicker remained within normal limits (refer to Figure 1a for percent deviations). A 34-month-old control (child with normal vision) has been included in the ERG traces for comparison.

Subject 6 was diagnosed with tuberous sclerosis at 2 months of age. He had a normal birth history but was delayed in development. His ERGs are shown in Figure 1b. His first ERG was recorded at 7 months of age after 7 days of vigabatrin treatment. His ERG was within normal limits for all tested stimuli except early photopic OPs (52% reduction). His initial dose of vigabatrin was 625 mg/day (69 mg/kg per day). After 6 months of vigabatrin treatment, ERG responses were within normal limits except for early OPs. These were diminished (76% reduction). After12 months of treatment, the dose of vigabatrin had increased to 115 mg/kg per day. The cone responses and flicker were within normal limits, however the early OPs had reduced (79% reduction). By the fourth visit (after 18 months on vigabatrin), at which time the dose of vigabatrin was increased to 125 mg/kg per day the cone b-wave, late OP, early OPs and flicker responses were all abnormally reduced (45, 79, 99 and 57% reduction, respectively). After 26 months of vigabatrin treatment, the flicker response worsened in amplitude, the cone b-wave increased in amplitude and the late OP and early OPs increased in amplitude but were still abnormally reduced (refer to Figure 1b for percent deviations). Interestingly, the rod-cone b-wave remained within normal limits. A 34-month-old control (child with normal vision) has been included in the ERG traces for comparison. By 37 months of age an ophthalmological examination of this child revealed the suggestion of vigabatrin toxicity (denoted by observable decrease in the retinal nerve fibre layer).

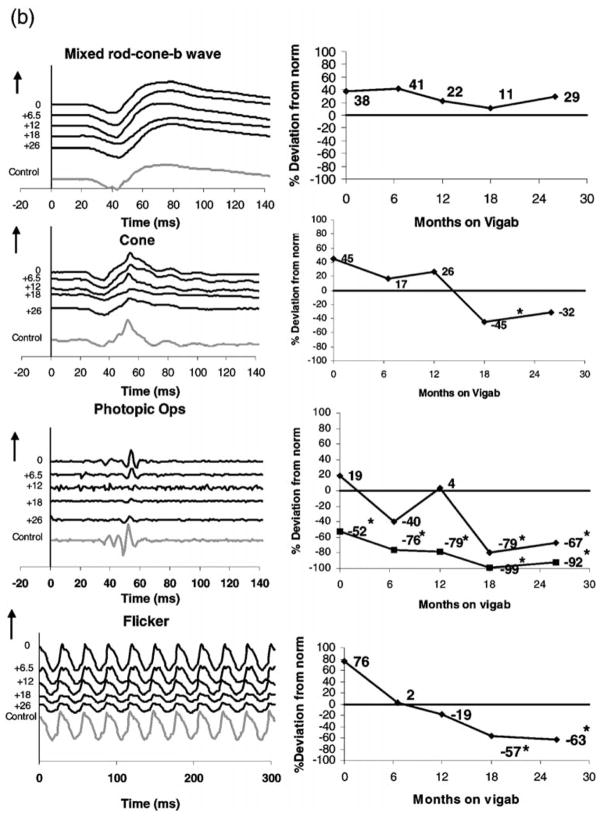

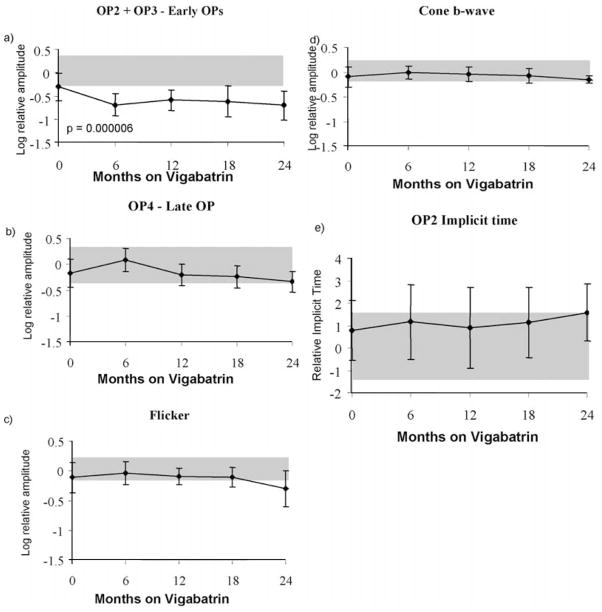

Longitudinal data of photopic ERG responses are shown in Figure 2. Using data from all 26 children, Figure 2a shows the early OP amplitude data. A paired t-test shows highly significant reduction in early OP amplitudes after 6 months on vigabatrin treatment (paired two-tail t-test; p = 2 × 10−6). The amplitudes reduced by 0.3 log units (50% reduction) between the baseline and 6-month follow-up visit. There was little change in OP amplitude after 6 months. The error bars describe the standard deviation. Grey shading describes the upper and lower limits of lab normal control data and contains 95% of responses for each ERG response described.

Figure 2.

(a–e) Mean ERG responses from children in the longitudinal vigabatrin study. Log relative amplitudes are plotted against length of time on vigabatrin (months). The error bars represent the standard deviation. Shaded areas represent lab normal ranges containing 95% of control data. (a) OP2+OP3 amplitude; (b) OP4 amplitude; (c) flicker amplitude; (d) cone b-wave amplitude; (e) photopic OP2 implicit time. Vertical arrows signify that the upward direction reflects increase in both amplitude and implicit time data. The flash intensity for the photopic single flash cone responses is 3.6 cds/m2 and the flicker flash intensity is 2.0 cds/m2.

Changes in amplitudes and implicit times of other ERG responses did not reach significance at the 0.005 α level required after Bonferroni correction for multiple t-tests. Descriptively the amplitude of OP4 showed a small increase, followed by some decline after 18 months of vigabatrin treatment. Flicker amplitude shows initial increase followed by decline (insignificant, p = 0.02) after 18 months of treatment. As described previously (Westall et al. [5]) the cone b-wave shows an initial increase followed by subsequent decrease after 18 months of vigabatrin treatment, showing a pattern similar to OP4 amplitude. The implicit time of OP2 shows increase after 18 months on vigabatrin treatment.

A statistical description of changes over time was accomplished by repeated measures ANOVA. The greatest effect was for the photopic early OPs. The prediction showed significant curvature (p = 0.0005) where the amplitude decreased after approximately 6 months and remained decreased for the duration of treatment. There was no significant change seen in the late OP4. The prediction for cone b-wave amplitude showed an initial increase (p = 0.04) after approximately 6 months, followed by a subsequent decrease after 18 months; a trend similar to that of the late OP. Analyses involving ERG implicit times showed no significant change of predicted value over time.

Discussion

Statistical analyses indicate significant yet differential effects of vigabatrin on the summed early OPs, late OP, cone b-wave and flicker amplitudes.

The early OP amplitudes were significantly reduced followed by slight recovery with chronic administration of vigabatrin (24 months). Although a decrease was seen in the late OP as well, this change was not remarkable.

There are three major wavelets that make up the photopic oscillatory potentials; individual OP wavelets have different origins and are thus differently susceptible to metabolic disturbance. The early OPs, which seem to be associated with the onset of brief flashes of light (ON response) are sensitive to GABA [13] while the late OP, which seem to be associated with the offset of brief flashes of light (OFF response) are sensitive to glycine blockers [14, 15].

The precise origins of the oscillatory potentials although unknown, may be a reflection of the synaptic activities in the inner retinal inhibitory feedback systems, which are initiated by amacrine cells [16].

The depolarisation of ON bipolar cells and the ON response of ON-OFF amacrine cells have been shown, in the mudpuppy retina, to be sensitive to GABA while the OFF cone bipolar cells are dominated by glycinergic input [13].

Picrotoxin, a pharmacological agent known to block GABA, was applied to frog eyecup preparations [17]. This application resulted in an increase in the b-wave of the ERG. The ERG b-wave has been shown to reflect ON-bipolar activity predominantly [18].

Vigabatrin administration in rats has been shown to produce a more than 6-fold increase in GABA levels in the retina compared with the cerebral cortex [19]. The amacrine cell layer, a major contributor to the formation of the OPs, is found to be the most abundant GABAergic retinal layer [20]. Hence the changes seen in the amplitude of the early OPs seem to reflect physiological changes in the inner retina that are sensitive to GABA. The improvement seen in Subject 49’s early OPs, after her vigabatrin dose was tapered from 147 to 43 mg/kg per day support the possibility that the early OPs merely reflect physiological changes that occur as a result of fluctuating GABA levels in the eye. Westall et al. [21] reported significant recovery of the early OP amplitude after vigabatrin treatment was discontinued. This confirms that the changes seen in the early OPs reflect physiological changes and not a toxic effect.

The unremarkable changes seen in the late OP amplitude further support studies, which report glycine neurotransmission being the main contributor to the generation of late OPs.

Interestingly, the flicker and cone b-wave amplitudes show a similar quadratic increase followed by decrease over time on vigabatrin.

The flicker response is generated via photoreceptoral and postphotoreceptoral activity [22]. This postphotoreceptoral activity may involve bipolar and inner retinal input and also ganglion cell input [23]. GABA receptors are present in bipolar cells [24] and ganglion cells [25, 26] as well as the amacrine cells, and thus alterations in GABA concentration may affect the generation of the flicker response.

The initial increase seen in the cone b-wave and flicker amplitude followed by a subsequent decrease in this study remains open to speculation. It is possible that GABA receptor differentiation may contribute to the changes being seen. Bipolar cells comprise of GABA-A and GABA-C receptors. GABA-C receptors have a much higher affinity for GABA than GABA-A [27] and activation of GABA-C receptors have been shown to increase the b-wave amplitude [28]. These findings may account for the shape of the cone b-wave and flicker amplitude.

Westall et al. [5] shows similar trends in amplitude of the cone b-wave and rod-cone b-wave, with an increase in amplitude seen after baseline visit. These findings support the ON system being implicated in vigabatrin’s effect on the visual system.

The above findings indicate that the photopic summed early OP amplitudes are clearly influenced by vigabatrin administration. The late OP amplitude however, remained relatively stable. These findings strongly suggest that these two systems are regulated by different mechanisms. It is also important to note however that the decreases seen in the early OP amplitudes were recovered once vigabatrin was discontinued. The effect of vigabatrin on the early OP amplitudes, therefore reflect primarily a physiological event and not a toxic one.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Rita Buffa for help with data collection, to Ajmal Kahn for help with deriving ERG normal ranges according to age and Dena Hammoudi for helping determine drug dosage and Tom Wright for helping with figures.

References

- 1.Daneshvar H, Racette L, Coupland SG, Kertes PJ, Guberman A, Zackon D. Symptomatic and asymptomatic visual loss in patients taking vigabatrin. Ophthalmology. 1999;106(9):1792–8. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(99)90345-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krauss GL, Johnson MA, Miller NR. Vigabatrin-associated retinal cone system dysfunction: electroretinogram and ophthalmologic findings [see comments] Neurology. 1998;50(3):614–8. doi: 10.1212/wnl.50.3.614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miller NR, Johnson MA, Paul SR, Girkin CA, Perry JD, Endres M, Krauss GL. Visual dysfunction in patients receiving vigabatrin: clinical and electrophysiologic findings. Neurology. 1999;53(9):2082–7. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.9.2082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harding GFA. Electrophysiological methods for assessing field losses associated with Vigabatrin. International Society for Clinical Electrophysiology of Vision XXXVIII Symposium; 2000; Sydney, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Westall CA, Logan WJ, Smith K, Buncic JR, Panton CM, Abdolell M. The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, Longitudinal ERG study of children on vigabatrin. Doc Ophthalmol. 2002;104(2):133–49. doi: 10.1023/a:1014656626174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Granit RL, Munsterhjelm A. The electrical response of dark adapted frog’s eye to monochromatic stimuli. J Physiol. 1937;88:436–58. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1937.sp003452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heckenlively JR, Arden GB, editors. Principles and Practice of Clinical Electrophysiology of Vision. St Louis, MO: Mosby Year Book, Inc; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ogden TE. The oscillatory waves of the primate electroretinogram. Vision Res. 1973;13(6):1059–74. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(73)90144-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wachtmeister L, Dowling JE. The oscillatory potentials of the mudpuppy retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1978;17(12):1176–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yanagida T, Koshimizu M, Kawasaki K, Yonemura D. Microelectrode depth study of the electroretinographic oscillatory potentials in the frog retina. Doc Ophthalmol. 1987;67(4):355–61. doi: 10.1007/BF00143953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lachapelle P, Benoit J. Interpretation of the filtered 100- to 1000-Hz electroretinogram. Doc Ophthalmol. 1994;86(1):33–46. doi: 10.1007/BF01224626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Westall CA, Panton CM, Levin AV. Time course for maturation of electroretinogram response, from infancy to adulthood. Doc Ophthalmol. 1999;96:355–79. doi: 10.1023/a:1001856911730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miller RF, Dacheux RF, Frumkes TE. Amacrine cells in Necturus retina: evidence for independent gamma- aminobutyric acid- and glycine-releasing neurons. Science. 1977;198(4318):748–50. doi: 10.1126/science.910159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Korol S, Leuenberger PM, Englert U, Babel J. In vivo effects of glycine on retinal ultrastructure and averaged electroretinogram. Brain Res. 1975;97(2):235–51. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(75)90447-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wachtmeister L. Further studies on the chemical sensitivity of the oscillatory potentials of the electroretinogram (ERG) 1. GABA-and glycine antagonists. Acta Ophthalmol. 1980;58:712–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1980.tb06684.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wachtmeister L. Oscillatory potentials in the retina: what do they reveal. Prog Retin Eye Res. 1998;17(4):485–521. doi: 10.1016/s1350-9462(98)00006-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Popova E, Penchev A. GABAergic control on the intensity-response function of the ERG waves under different background illumination. Biomed Biochim Acta. 1990;49(10):1005–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stockton RA, Slaughter MM. B-wave of the electroretinogram. A reflection of ON bipolar cell activity. J Gen Physiol. 1989;93(1):101–22. doi: 10.1085/jgp.93.1.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Neal MJ, Shah MA. Development of tolerance to the effects of vigabatrin (gamma-vinyl-GABA) on GABA release from rat cerebral cortex, spinal cord and retina. Br J Pharmacol. 1990;100(2):324–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1990.tb15803.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Graham LT. Intraretinal distribution of GABA content and GAD activity. Brain Res. 1972;36(2):476–9. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(72)90759-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Westall CA, Nobile R, Morong S, Buncic JR, Logan WJ, Panton CM. Changes in the electroretinogram resulting from discontinuation of vigabatrin in children. Doc Ophthalmol. 2003;107:299–309. doi: 10.1023/b:doop.0000005339.23258.8f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kondo M, Sieving PA. Postphotoreceptoral activity dominates primate photopic 32-Hz ERG for sine-, square-, and pulsed stimuli. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43(7):2500–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bush RA, Sieving PA. Inner retinal contributions to the primate photopic fast flicker electroretinogram. J Opt Soc Am A. 1996;13(3):557–65. doi: 10.1364/josaa.13.000557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koulen P, Malitschek B, Kuhn R, Bettler B, Wassle H, Brandstatter JH. Presynaptic and postsynaptic localization of GABA(B) receptors in neurons of the rat retina. Eur J Neurosci. 1998;10(4):1446–56. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1998.00156.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perez MT, Davanger S. Distribution of GABA immunoreactivity in kainic acid-treated rabbit retina. Exp Brain Res. 1994;100(2):227–38. doi: 10.1007/BF00227193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Davson H. Physiology of the eye. London: MacMillan; 1990. Transmitters in the retina; pp. 343–52. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Qian H, Dowling JE. Novel GABA responses from rod-driven retinal horizontal cells. Nature. 1993;361(6408):162–4. doi: 10.1038/361162a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kapousta-Bruneau GABA a and GABA c receptor antagonists have opposite effects on the B-wave of ERG in rat retina. IOVS. 1998;39 (Suppl):S980. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(00)00028-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]