Abstract

Purpose/Objectives

To describe the sleep characteristics of family caregivers of individuals with a primary malignant brain tumor (PMBT).

Design

Cross-sectional, correlational design using baseline data from a longitudinal study.

Setting

Neuro-oncology and neurosurgery clinics at an urban tertiary medical center in the United States.

Sample

133 family caregivers recruited one to two months following diagnosis of family member’s PMBT.

Methods

Subjective and objective measures of sleep were obtained via self-report and the use of accelerometers (three nights).

Main Research Variables

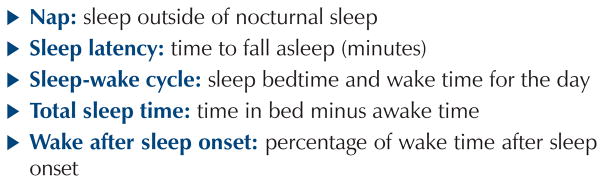

Sleep characteristics including sleep latency, total sleep time, wake after sleep onset, number of naps, number of arousals, sleep-wake cycle, and sleep quality.

Findings

Sleep latency in caregivers was, on average, 35 minutes (SD = 34.5)—more than twice as long as the norm of 15 minutes (t[113]) = 6.18, p < 0.01). Caregivers averaged a total sleep time of 5 hours and 57 minutes (SD = 84.6), significantly less than the recommended 7 hours (t[113] = −8, p < 0.01), and were awake in the night 15% of the time, significantly more than the norm of 10% (t[111] = 5.84, p < 0.01). Caregivers aroused an average of 8.3 times during nocturnal sleep (SD = 3.5, range = 2–21), with about 32% reporting poor or very poor sleep quality.

Conclusions

Caregivers experienced sleep impairments that placed them at risk for poor mental and physical health, and may compromise their ability to continue in the caregiving role.

Implications for Nursing

Nurses need to assess sleep in caregivers of individuals with PMBT and implement interventions to improve sleep.

Knowledge Translation

Sleep deprivation is common in family caregivers during the early stages of care for individuals with a PMBT. A single-item sleep quality question could be an easy but valuable tool in assessing sleep disturbances in family caregivers of individuals with a PMBT. The health trajectory of family caregivers warrants further longitudinal study, in addition to the examination of the bidirectional relationship of health status of care recipients and their family caregiver.

The physical and emotional burden of providing care includes sleep disturbances that have been shown to worsen physical and mental health (Brummett et al., 2006; Castro et al., 2009; Kochar, Fredman, Stone, & Cauley, 2007; McCurry, Logsdon, Teri, & Vitiello, 2007; Perrin, Heesacker, Stidham, Rittman, & Gonzalez-Rothi, 2008). With the cognitive and physical impairments resulting from a primary malignant brain tumor (PMBT) and its treatment, the care of individuals with a PMBT often falls on the family (Sherwood et al., 2006). Although PMBTs are rare, comprising only 2% of all cancers, these tumors are associated with significant morbidity and mortality (Omay & Vogelbaum, 2009; Schnell & Tonn, 2009). PMBTs typically present in men aged in their mid-60s or older, often with focal deficits such as headaches, memory loss, cognitive changes, motor deficits, language deficits, and/or sensory deficits (Chandana, Movva, Arora, & Singh, 2008; Omay & Vogelbaum, 2009; Schnell & Tonn, 2009). The average life expectancy after diagnosis with a high-grade PMBT, the most common type, is 14 months (Omay & Vogelbaum, 2009). Providing care to a person with a PMBT involves managing cognitive and physical deficits that become worse throughout the trajectory. Caregivers typically are older female spouses (Cashman et al., 2007; Keir et al., 2006; Muñoz et al., 2008; Salander & Spetz, 2002; Schmer, Ward-Smith, Latham, & Salacz, 2008; Sherwood, Given, Doorenbos, & Given, 2004; Sherwood et al., 2006, 2007; Wideheim, Edvardsson, Påhlson, & Ahlström, 2002). Few studies of caregivers of individuals with a PMBT exist and, although reports of sleep disturbances have been noted, no studies of sleep have been reported in this unique caregiving population.

Literature Review

Normal Sleep

Researchers have hypothesized that sleep functions to restore the brain and to create memory through encoding and consolidation. Sleep-wake occurs in a rhythmic and cyclic pattern influenced by complex physiologic and behavioral processes (Carskadon & Dement, 2011). Sleep must occur in a regular pattern with minimal disruptions to mediate stress; provide emotional, mental, and physical energy; and support hormonal release and neuronal restoration (Carskadon & Dement, 2011). The American Academy of Sleep Medicine ([AASM], 2010) has recommended seven hours of sleep for restoration, with a sleep onset after laying down of less than 15 minutes and no more than 10% wake time during the nocturnal sleep period for the adult population.

Sleep Impairments in Family Caregiving

For family caregivers, interruptions in routine optimal sleep are multifactorial and can result from physiologic and emotional effects as well as the effects of providing care (Brummett et al., 2006; McCurry et al., 2007). Age, gender, and the presence of comorbidities have been shown to be consistently associated with impaired sleep in caregivers of those with cancer (Berger et al., 2005). Older age (Fonareva, Amen, Zajdel, Ellingson, & Oken, 2011; Kochar et al., 2007; McCurry et al., 2007) and being female (Castro et al., 2009; Kochar et al., 2007) have been associated with poorer sleep quality; however, the presence of comorbidities may play a more important role in sleep disturbances (Berger et al., 2005). Poor sleep hygiene as reflected in irregular sleep-wake schedules and naps longer than 30 minutes, caffeine and alcohol intake, and smoking prior to lying down for nocturnal sleep are other caregiver habits that may affect sleep (Berger et al., 2005; Lee, 2003). Sleep characteristics in caregivers differ from noncaregivers when measured with portable polysomnography (PSG); caregivers take longer to fall asleep and spend less time in the restorative phases of sleep (Fonareva et al., 2011).

Emotional distress in the forms of caregiver burden and depression, anxiety, and bereavement may result in sleep disturbances for family caregivers (Brummett et al., 2006; McCurry et al., 2007; Vaz Fragoso & Gill, 2007). Family caregivers with depressive symptoms are twice as likely to report sleep disturbances than noncaregivers and caregivers with low levels of depressive symptoms (Kochar et al., 2007). In addition, family caregivers experience disruptions in sleep from awakenings by the care recipient or from feelings of “being on duty” (Brummett et al., 2006, p. 223). Frequent nocturnal disruptions are associated with more depressive symptoms and poorer caregiver mental health (Creese, Bédard, Brazil, & Chambers, 2008). Distinct from other caregiving populations, such as dementia and other forms of cancer, caregivers of those with PMBTs must cope with the rapid neurocognitive and physical decline of their family member, which may exacerbate sleep impairments.

Effects of Sleep Losses

Whether chronic sleep losses are the result of deprivation or disruption, these losses increase a person’s risk of adverse physical, cognitive, and emotional outcomes (Dinges, Rogers, & Baynard, 2011; Lee et al., 2004). Adverse physical responses can include alterations in immune functioning (von Känel et al., 2006), alterations in metabolic or endocrine functioning (Moldofsky, 1995), and increases in comorbidities such as hypertension (von Känel et al., 2006) and depression (Hamilton, Nelson, Stevens, & Kitzman, 2007). Cognitive impairments can include short-term memory loss, poor problem solving and coping, and increases in number of accidents and/or errors in judgment (Bonnet, 2011; Dinges et al., 2011). Emotional effects can include alterations in mood and low motivation (Hamilton et al., 2007), as well as changes in social interactions with family, colleagues, and friends (Lee, 2003). Those with sleep fragmentation have more cognitive impairments than people with shortened sleep times (Bonnet, 2011). The purpose of this study was to determine the sleep quality and quantity of family caregivers of individuals with a PMBT at time of diagnosis and to examine factors contributing to their sleep characteristics.

Methods

Design

A cross-sectional, correlational study was conducted using baseline data (one to two months after PMBT diagnosis) from a larger parent study of mind-body interactions in family caregivers of those with a PMBT (Mind-Body Interactions in Neuro-Oncology Caregivers, National Cancer Institute RO1 [CA118711-02], Sherwood, PI, 2007).

Sample and Setting

Caregivers were identified by care recipients as the person who would be providing the majority of emotional, financial, and/or physical support. Caregivers were not required to live with or be a blood relative of the care recipient. Eligibility criteria for family caregivers in the parent study included (a) being aged 21 years or older; (b) being able to read, write, and understand English; (c) having access to a telephone; (d) not being a primary caregiver for anyone else other than children younger than 21 years; and (e) not being a professional caregiver. Care recipients were outpatients at an urban tertiary medical center in the eastern United States.

Instruments

Subjective measure of family caregiver sleep quality

The sleep quality of family caregivers was measured using the sleep quality subscale, which is a single-item of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) (Buysse, Reynolds, Monk, Berman, & Kupfer, 1989), an instrument that measures sleep quality and habits in the prior month. The PSQI sleep quality subscale has a four-point scale ranging from 0 (very good) to 3 (very bad). Higher scores reflect poorer sleep quality (Buysse et al., 1989). The PSQI is a well-established and widely used valid and reliable instrument (Grutsch et al., 2011). The single-item sleep quality subscale had an overall correlation coefficient of 0.83 (p < 0.01) with the global score in the original PSQI psychometric testing (Buysse et al., 1989).

Objective measures of family caregiver sleep

A Bodymedia® Sensewear™ Armband, an accelerometer device containing two-axis microelectromechanical sensors, was used for the objective sleep measurements total sleep time (TST), wake after sleep onset (WASO), sleep latency, naps, and sleep-wake cycle (see Figure 1). The armband has been validated with PSG measurements (Sunseri et al., 2009). The study participants were asked to wear the armband for three 24-hour periods; however, because of missing data, the average of a minimum of two nights TST and WASO were used for final analysis.

Figure 1. Operational Definitions of Sleep Variables.

Note. Based on information from Lee, 2003.

Sleep onset was defined as the first 30-minute or longer period of nocturnal sleep after lying down. Sleep-wake cycle was determined by synchronization between each day’s bedtime and wake time.

Measures of mood variables known to affect family caregiver sleep

Caregiver anxiety was measured using the shortened Profile of Mood States–Anxiety (POMS-anxiety) scale. The shortened POMS was developed to assess transient distinct mood states (McNair, Lorr, & Droppleman, 1971; Shacham, 1983). The tension-anxiety subscale includes three items rated on a five-point scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always). The total subscale score ranges from 5–15, with higher scores indicating more anxiety. Discriminant validity has been established in patients with cancer (Cella et al., 1987). Cronbach alphas for the tension-anxiety subscale range from 0.87–0.91 (Baker, Denniston, Zabora, Polland, & Dudley, 2002; Curran, Andrykowski, & Studts, 1995). The Cronbach alpha for this study was 0.9.

Caregiver depressive symptoms were measured using the 10-item short form of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression (CES-D) scale (Andresen, Malmgren, Carter, & Patrick, 1994) derived from the original instrument (Radloff, 1977). Criterion validity for the CES-D short form has been established using the full CES-D (Cheung, Liu, & Yip, 2007). Each item has a four-point response scale ranging from 0 (rarely) to 3 (most or all of the time) and reflects the symptom frequency experienced in the prior week. Total scores on the 10-item CES-D range from 0–30, with higher scores indicating more depressive symptoms and a cut-off score of 10 or higher indicating possible clinical depression (Martens et al., 2006). Andresen et al. (1994) found a good predictive accuracy with the 10-item CES-D (kappa = 0.97, p < 0.01). The Cronbach alpha for this study was 0.87.

Sociodemographic variables

Self-reported caregiver sociodemographic data included age, gender, ethnicity, educational level, comorbidities, employment, smoking status, and weight. Care recipient demographic data included tumor status verified by pathology report and age collected from the health record. The care recipients’ performance of activities of daily living (ADLs) was measured by trained research assistants (RAs) using the Karnofsky Performance Scale (KPS) (Karnofsky, Abelmann, Craver, & Burchenal, 1948). The validity and reliability of the KPS have been established with other measures of physical performance (Simmonds, 2002; Yates, Chalmer, & McKegney, 1980).

Procedures

After the identification of a PMBT, the caregiver and care recipient were approached for consent while in the clinic. Both members had to consent to participate. Data were collected by trained RAs. Care recipient data were collected from the health record and by in-person interview at time of consent. After consent, caregivers were given instructions to wear the Bodymedia Sense-wear Armbands for three consecutive 24-hour days. The armbands were calibrated prior to participant use. Once data collection was complete, the armband was returned to the study coordinator via prepaid mailed package. Within 72 hours of the care recipient’s interview, caregiver data using standardized questionnaires were collected via a telephone interview by RAs using a standardized protocol. Referrals to primary care providers were made for those participants scoring 10 or greater on the CES-D.

Data Analyses

Data were analyzed with PASW Statistics 18 for Windows ®. Descriptive statistics were used to describe sample characteristics and major study variables. Bivariate correlation coefficients were used to examine relationships among sleep variables, caregiver mood variables, and caregiver and care recipient demographic variables, and to finalize variables to be included in regression modeling. Independent t tests were used to compare differences between groups. One-sample t tests were used to compare sample means with the general population on select sleep variables. Hierarchical regression was used to examine the contribution of care recipient and caregiver characteristics to selected sleep variables.

Results

From October 1, 2005, through April 30, 2011, 155 caregiver and care recipient dyads were enrolled in the study. Of those, 22 dyads (14%) did not complete the measures. The care recipients who did not complete measures were significantly older (X̄ = 62.1, SD = 18.4) than those who did complete measures (X̄ = 53.3, SD = 13.9, t[14] = 2.24, p = 0.03); no other significant differences were found.

Sample Characteristics

The final sample included 133 primary family caregiver and care recipient dyads. The care recipients predominantly were middle-aged men with a grade IV malignant glioma (glioblastoma multiforme) who were Caucasian, married with a spousal caregiver, and well educated. The care recipients had high physical functioning, with 52 (39%) reporting no complaints or minor symptoms, 25 (19%) requiring minimal assistance with care, and 12 (9%) needing assistance with ADLs (see Table 1). Fifteen care recipients (11%) required considerable assistance or were unable to carry on normal activity.

Table 1.

Care Recipient Characteristics (N = 133)

| Characteristic | X̄ | SD | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) (N = 131) | 53.29 | 13.87 | 22–85 |

| KPS (N = 114) | 82.63 | 12.63 | 50–100 |

| Characteristic | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 85 | 64 |

| Female | 48 | 36 |

| Tumor type | ||

| Astrocytoma I | 2 | 2 |

| Astrocytoma II | 5 | 4 |

| Astrocytoma III | 11 | 8 |

| Glioblastoma multiforme | 66 | 50 |

| Oligodendroglioma | 19 | 14 |

| Other | 12 | 9 |

| Missing | 18 | 13 |

KPS—Karnofsky Performance Scale

Note. The KPS ranges from 0 (death) to 100 (perfect health).

Caregivers were predominately Caucasian, middle-aged females, married, and the spouse or significant other of the care recipient (see Table 2). Caregivers were well educated and most were employed outside the home. The majority of the caregivers was overweight or obese and reported at least one comorbidity such as high blood pressure, diabetes, cancer, and or stroke.

Table 2.

Caregiver Characteristics (N = 133)

| Characteristic | X̄ | SD | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) (N = 130) | 51.59 | 11.81 | 21–77 |

| Years of formal education | 14.42 | 2.71 | 5–23 |

| Number of children | 2.42 | 2.17 | 0–19 |

| Number of children in home | 0.63 | 0.99 | 0–4 |

| Number of comorbidities | 1.06 | 1.15 | 0–8 |

| Weight status (body mass index) | 27.63 | 6.1 | 16.8–47.1 |

| Characteristic | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 92 | 69 |

| Male | 38 | 29 |

| No response | 3 | 2 |

| Race | ||

| Caucasian | 125 | 94 |

| Black | 2 | 2 |

| Asian | 2 | 2 |

| American Indian | 1 | – |

| No response | 3 | 2 |

| Relationship to care recipient | ||

| Spouse or significant other | 100 | 75 |

| Daughter or son | 11 | 8 |

| Parent | 10 | 8 |

| Friend, companion, or other | 9 | 7 |

| No response | 3 | 2 |

| Marital status | ||

| Currently married or living with significant other | 120 | 90 |

| Widowed, separated, or divorced | 7 | 5 |

| Never married | 3 | 2 |

| No response | 3 | 2 |

| Employment status | ||

| Full- or part-time | 74 | 56 |

| Retired, homemaker, or other | 42 | 32 |

| Laid off or unemployed | 14 | 11 |

| No response | 3 | 2 |

| Have children | ||

| Yes | 112 | 84 |

| No | 18 | 14 |

| No response | 3 | 2 |

| Number of comorbidities | ||

| Zero | 38 | 29 |

| One | 40 | 30 |

| Two | 22 | 17 |

| Three | 6 | 5 |

| Four or more | 2 | 2 |

| No response | 25 | 19 |

| Smoking status | ||

| Nonsmoker | 96 | 72 |

| Smoker | 19 | 14 |

| No response | 18 | 14 |

| Weight | ||

| Underweight | 5 | 4 |

| Normal weight | 37 | 28 |

| Overweight | 38 | 29 |

| Obese | 36 | 27 |

| No response | 17 | 13 |

Note. Because of rounding, not all percentages total 100.

Caregiver Sleep Characteristics

On average, caregiver sleep latency was 35 minutes (SD = 34.5, median [Mdn] = 24.5), more than twice as long as the general population norm of 15 minutes (t[113] = 6.18, p < 0.01) (AASM, 2010). Average TST was 5 hours and 57 minutes (SD = 84.6, Mdn = 361.3 minutes), less than the general population’s minimum of seven hours (t[113] = −8, p < 0.01) (AASM, 2010). Caregivers experienced fragmented sleep (WASO X̄ = 15.1%, SD = 9.2%, Mdn = 13.1%). Male caregivers slept less than female caregivers (X̄ = 328, SD = 85.6 minutes versus X̄ = 368, SD = 82.1 minutes, t[31] = 2.61, p = 0.01).

Caregiver self-perceptions of sleep latency differed significantly from that of the accelerometer data (X̄ = 24.9, SD = 26.8 minutes versus X̄ = 35.4, SD = 34.5 minutes, t[11] = 3.1, p < 0.01). Caregivers also perceived less WASO time (11%) than what was recorded by the accelerometer (15%, t[111] = 5.26, p < 0.01).

On average, caregivers awakened at 7:09 am (SD = 120.84 minutes, range = 3:36 am–10:35 am), aroused an average of 8.3 times (SD = 3.5, range = 2–21) during the night as reflected on the accelerometers, and adhered to an average bedtime of 11:04 pm (SD = 111.43 minutes, range = 8:44 pm–2:22 am). Forty-eight percent of caregivers napped at least once per day (SD = 0.7, range = 0–5) for an average of 16.4 minutes (SD = 23.5, range = 0–121). Self-reported sleep quality was fairly good to good for the majority of caregivers (61%, n = 81); however, 32% (n = 42) of the caregivers reported fairly poor or very poor sleep quality.

To determine the synchronicity of the sleep-wake cycle, bivariate correlations were calculated for the caregiver bedtimes and arousal times. The sleep-wake cycle of this sample was asynchronous as evidenced by asynchronous patterns between sleep and wake schedules. Participant bedtimes were moderately correlated among the three days (r = 0.41–0.46, p < 0.01). Their arousal times showed a variety of relationships: (a) a strong relationship between sleep arousal on day 1 and day 2 (r = 0.57, p < 0.01), (b) a moderate relationship between day 2 and day 3 (r = 0.43, p < 0.01), and (c) a small relationship between day 1 and day 3 (r = 0.29, p < 0.01). Day of the week was examined for impact on sleep characteristics and no significant difference was found (p > 0.05).

Caregiver Mood Characteristics

The average caregiver anxiety score was 8.4 (SD = 2.2, range = 3–15, n = 122). About 59% of the caregivers reported high anxiety (n = 79). The average CES-D score was 8.3 on the 0–30 scale (SD = 6.5, range = 9–29, n = 126). About 31% of caregivers (n = 41) reported depressive symptoms suggestive of a need for referral for evaluation of possible clinical depression (scores of 10 or greater on the CES-D).

Relationships Among the Study Variables

Among the sleep variables, poorer self-reported sleep quality was associated with longer TST (r = 0.21, p = 0.03) and increased sleep latency (rs = 0.23, p = 0.02). No significant relationship existed between WASO and self-reported sleep quality (r = −0.18, p = 0.07).

Significant associations (p < 0.05) were found among the caregiver characteristics and sleep variables, including (a) longer TST correlated for female caregivers and those with higher anxiety and caring for higher physically functioning care recipients; (b) less WASO associated with being employed, higher physically functioning care recipients, and higher caregiver anxiety; and (c) higher caregiver anxiety associated with poorer sleep quality (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Correlations Among Caregiver Characteristics and Sleep Variables

| Variable | TST | WASO | Sleep Qualitya | Sleep Latencyb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ageb | −0.07 | −0.02* | −0.03 | −0.11 |

| Genderb | 0.21* | 0.00 | −0.1 | −0.06 |

| Raceb | −0.15 | 0.11 | −0.11 | 0.09 |

| Years of education | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.02 |

| Relationship to CR | 0.00 | −0.16 | −0.08 | −0.06 |

| Employment status | 0.1 | −0.19* | 0.03 | 0.11 |

| Smoking statusb | −0.12 | 0.02 | 0.13 | 0.15 |

| Number of comorbidities | −0.09 | −0.04 | −0.01 | −0.14 |

| Body mass index | −0.12 | 0.07 | −0.05 | −0.02 |

| CR tumor type | −0.02 | 0.03 | −0.09 | −0.09 |

| CR Karnofsky score | 0.22* | −0.21* | −0.04 | 0.06 |

| POMS-Anxiety | 0.25** | −0.24* | 0.39** | 0.16 |

| CES-D | −0.01 | −0.06 | −0.16 | 0.00 |

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01

Sleep quality item from Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index

Spearman’s rho reported

CES-D—Center for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression; CR—care recipient; POMS—Profile of Mood States; TST—total sleep time; WASO—wake after sleep onset

Predictors of Total Sleep Time, Wake After Sleep Onset, and Sleep Quality

Three parsimonious models, using hierarchical regression modeling, were constructed using variables that were significantly (p < 0.05) correlated with the sleep variables: TST, WASO, and sleep quality. The first model indicated higher care recipient physical functioning (t = 2, p = 0.05), and higher caregiver anxiety (t = 2.1, p = 0.04) predicted longer nocturnal sleep times. The overall model was significant and accounted for 14% of the variance in TST. In the second model, poorer care recipient physical functioning (t = −2.1, p = 0.04), not being employed (t = −2.5, p = 0.01), and lower anxiety (t = −2.4, p = 0.02) were significant predictors of higher WASO. All together, these three predictors accounted for 15% of the variance in WASO. In the final sleep quality model, higher caregiver anxiety predicted poorer self-reported sleep quality, and accounted for 15% of the variance (t = 0.36, p < 0.01) (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Variables Associated With Caregiver Sleep

| Predictor | TST (N = 91)

|

WASO (N = 90)

|

Sleep Qualitya (N = 118)

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE B | β | ΔR2 | B | SE B | β | ΔR2 | B | SE B | β | ΔR2 | |

| Step 1: Sociodemographics | ||||||||||||

| Gender | 11.7 | 18.6 | 0.07 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| KPS | 1.3 | 0.65 | 0.21* | 0.05 | −0.15 | 0.07 | −0.2* | – | – | – | – | – |

| Employment status | – | – | – | – | −0.48 | 1.9 | −0.26* | 0.09* | – | – | – | – |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Step 2: Mood variables | ||||||||||||

| POMS-Anxiety | 7.1 | 3.5 | 0.23* | 0.08** | −0.87 | 0.37 | −0.24* | 0.06* | 0.12 | 0.03 | 0.39** | 0.15** |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Step 3: Subjective sleep | ||||||||||||

| Sleep quality | 12.9 | 11.9 | 0.12 | 0.01 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01

Sleep quality item from Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index

B—unstandardized regression coefficient; KPS—Karnofsky Performance Scale; POMS—Profile of Mood States; SE—standard error; TST—total sleep time; WASO—wake after sleep onset

Note. Total R2 = 0.14* for TST, 0.15* for WASO, and 0.15* for sleep quality.

Note. Overall models are as follows: for TST, F[4,87] = 3.59, p = 0.009; for WASO, F[3,87] = 4.92, p = 0.003; for sleep quality, F[1,117] = 20.86, p ≤ 0.001

Discussion

The PMBT caregivers in this study slept less than the recommended total sleep time and experienced fragmented sleep similar to family caregivers of those with dementia (Beaudreau et al., 2008; Castro et al., 2009; Fonareva et al., 2011; Rowe, Kairalla, & McCrae, 2010; Rowe, McCrae, Campbell, Benito, & Cheng, 2008) and those with cancer (Carter, 2005, 2006). Sleep impairments such as fragmentation of sleep or shorter sleep times have negative effects on caregiver health. Fragmented sleep is associated with cognitive impairments that affect task attention, acquisition of new knowledge, and short-term memory (Bonnet, 2011; Cole & Richards, 2005; Dinges et al., 2011). Consistent with other caregiving studies, findings in this study indicate that PMBT caregivers are vulnerable and may be at risk for depression, cardiovascular disease, and higher mortality rates (Hamilton et al., 2007; Moldofsky, 1995; Schulz & Beach, 1999). For caregivers, impaired cognitive function may interfere with their ability to make decisions for their care recipient or the ability to remain in the caregiving role. Although individually shorter sleep times, longer sleep latencies, and frequent awakenings during sleep may not appear significant, together and cumulatively they can lead individuals to incur a sleep debt (Van Dongen, Rogers, & Dinges, 2003) that does not allow for the restorative function of sleep (AASM, 2010; Bonnet, 2011) and can ultimately compromise their physical and mental functioning. In addition, those PMBT caregivers who are not able to fall asleep in what is perceived to be a timely manner without intervention are at a higher risk for developing anxiety from the prolonged sleep latency, which may further disturb sleep (Lee, 2003; Stepanski & Wyatt, 2003).

Healthy sleep is characterized by at least seven hours of nocturnal sleep and fewer awakenings (AASM, 2010). In this study, findings from self-reported sleep quality were significantly different from the objective data measured from the accelerometers. Compared to the objective sleep data, the caregivers underestimated their sleep latencies and arousals; however, these differences are consistent with findings in those with chronic sleep restrictions (Dinges et al., 2011).

Anxiety was a consistent predictor of caregiver sleep quality, sleep duration, and nocturnal arousals. Anxiety disorders typically include symptoms such as longer sleep latencies, difficulty maintaining sleep in the night, and shorter sleep durations (Monti & Monti, 2000; Papadimitriou & Linkowski, 2005; Stein & Mellman, 2011). However, higher anxiety in caregivers was unexpectedly associated with longer total sleep times and less WASO. That may have resulted from a combination of anxiety and depressive symptoms. Studies have indicated that people experiencing depressive symptoms report poorer sleep quality, whereas those with anxiety report longer sleep latencies (Babson, Trainor, Feldner, & Blumenthal, 2010; Mayers, Grabau, Campbell, & Baldwin, 2009). Additional studies are needed to fully elucidate the role that anxiety has in sleep. Anxiety was the only predictor of poor sleep quality, which is similar to other caregiving populations (Berger et al., 2005; McCurry et al., 2007).

Care recipient physical functioning was another independent predictor of total sleep time and arousals. Caregivers of care recipients with higher physical functioning had longer total sleep times, whereas caregivers of those with lower physical functioning had more WASO. Although not addressed in the caregiving literature, these findings make logical sense, as caregivers may be awakened in the night to provide care for those care recipients needing more assistance with activities such as toileting.

Those who were employed experienced less WASO. The effects of employment on sleep have not been reported in the caregiving literature; however, those who are employed may experience a better sleep-wake schedule because the regular work schedule drives a consistent wake time, resulting in better sleep. Another explanation may be that with higher fatigue may come a higher propensity to sleep. Additional study of the relationships among sleep, employment, and caregiving is needed.

Caregiver sleep was impaired at the time of PMBT diagnosis. Although whether these initial impairments continue, worsen, or improve given the trajectory of the illness and increasing care recipient disability is unknown, sleep impairments likely continue or worsen. Primary studies that specifically address sleep in PMBT caregivers are needed because sleep impairments may affect caregiver ability to make decisions, provide care, and handle personal health.

Limitations

The literature suggests that when using actigraphy, similar to accelerometers, a minimum of three with a preference for five nights (Acebo & LeBourgeois, 2006; Morgenthaler et al., 2007) of data are needed to provide a clearer representation of participant sleep. However, to prevent undue stress on caregivers of patients with PMBT, the authors collected three 24-hour periods of data and, because of missing data, used a minimum of two 24-hour periods of data for analysis, which may not be an accurate representation of caregivers’ sleep patterns. The majority of caregivers, although reflective of the incidence of PMBTs, were Caucasian and well-educated, which poses a threat to external validity.

Implications for Nursing Practice

With much of the care for individuals with a PMBT occurring in the home, healthcare providers need to be cognizant of the burdens on caregiver sleep and health. Healthcare providers’ interactions with PMBT caregivers need to include brief assessments of anxiety, depressive symptoms, and sleep in hospital and clinic settings. For those caregivers with high anxiety or depressive symptoms, teaching ways to cope with anxiety or making referrals when appropriate for counseling could contribute to preserving or improving caregivers’ health. Written information about sleep and ways to improve sleep are needed for all caregivers, particularly as the current study found caregivers underestimate their sleep loss and may not realize the potential effects of poor sleep on their cognition. The information should include sleep hygiene content such as the habits and practices that may hinder or improve sleep, such as going to bed and arising at the same time each day or avoiding heavy meals, extreme exercise, alcohol, caffeine, or nicotine before laying down to sleep (AASM, 2010; Mastin, Bryson, & Corwyn, 2006; Qidwai, Baqir, Baqir, & Zehra, 2010). Minimization of sleep distractions such as watching television, using a computer, or cleaning the house prior to attempting to sleep should be discussed, as well as an assessment of the sleep environment for loud noises, bright lights, or pets (AASM, 2010; Mastin et al., 2006; Qidwai et al., 2010). Caregivers who experience difficulty in falling asleep should be encouraged to get out of bed after 20 minutes and try again when they feel sleepy (AASM, 2010; Berger et al., 2009). If the caregivers experience shortened total sleep times, taking a nap limited to 30–45 minutes during the day (AASM, 2010; Berger et al., 2009) may help reduce sleep loss. For those with shortened sleep times because of caregiving demands, caregivers should be encouraged to seek respite through other family members and friends. Through awareness of potential sleep impairments, systematic assessments of caregiver sleep and health, and provision of information about sleep hygiene, nurses are in an ideal position to improve PMBT caregivers’ sleep, health, and quality of life.

Acknowledgments

Support for this research was provided, in part, by the National Cancer Institute Mind-Body Interactions in Neuro-Oncology Caregivers Grant R01 (CA118711-02) awarded to Sherwood. Mention of specific products and opinions related to those products do not indicate or imply endorsement by the Oncology Nursing Forum or the Oncology Nursing Society.

References

- Acebo C, LeBourgeois MK. Actigraphy. Respiratory Care Clinics of North America. 2006;12:23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.rcc.2005.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Practice guidelines. 2010 Retrieved from http://www.aasmnet.org/practiceguidelines.aspx.

- Andresen EM, Malmgren JA, Carter WB, Patrick DL. Screening for depression in well older adults: Evaluation of a short form of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale) American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1994;10:77–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babson KA, Trainor CD, Feldner MT, Blumenthal H. A test of the effects of acute sleep deprivation on general and specific self-reported anxiety and depressive symptoms: An experimental extension. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 2010;41:297–303. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2010.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker F, Denniston M, Zabora J, Polland A, Dudley WN. A POMS short form for cancer patients: Psychometric and structural evaluation. Psycho-Oncology. 2002;11:273–281. doi: 10.1002/pon.564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaudreau SA, Spira AP, Gray HL, Depp CA, Long J, Rothkopf M, Gallagher-Thompson D. The relationship between objectively measured sleep disturbance and dementia family caregiver distress and burden. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology. 2008;21:159–165. doi: 10.1177/0891988708316857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger AM, Kuhn BR, Farr LA, Lynch JC, Agrawal S, Chamberlain J, Von Essen SG. Behavioral therapy intervention trial to improve sleep quality and cancer-related fatigue. Psycho-Oncology. 2009;18:634–646. doi: 10.1002/pon.1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger AM, Parker KP, Young-McCaughan S, Mallory GA, Barsevick AM, Beck SL, Hall M. Sleep wake disturbances in people with cancer and their caregivers: State of the science [Online exclusive] Oncology Nursing Forum. 2005;32:E98–E126. doi: 10.1188/05.ONF.E98-E126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnet MH. Acute sleep deprivation. In: Kryger MH, Roth T, Dement WC, editors. Principles and practice of sleep medicine. 5. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2011. pp. 54–66. [Google Scholar]

- Brummett BH, Babyak MA, Siegler IC, Vitaliano PP, Ballard EL, Gwyther LP, Williams RB. Associations among perceptions of social support, negative affect, and quality of sleep in caregivers and noncaregivers. Health Psychology. 2006;25:220–225. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.25.2.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Research. 1989;28:193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carskadon MA, Dement WC. Normal human sleep: An overview. In: Kryger MH, Roth T, Dement WC, editors. Principles and practices of sleep medicine. 5. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2011. pp. 13–23. [Google Scholar]

- Carter PA. Bereaved caregivers’ descriptions of sleep: Impact on daily life and the bereavement process [Online exclusive] Oncology Nursing Forum. 2005;32:E70–E75. doi: 10.1188/05.ONF.E70-E75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter PA. A brief behavioral sleep intervention for family caregivers of persons with cancer. Cancer Nursing. 2006;29:95–103. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cashman R, Bernstein LJ, Bilodeau D, Bovett G, Jackson B, Yousefi M, Perry J. Evaluation of an educational program for the caregivers of persons diagnosed with a malignant glioma. Canadian Oncology Nursing Journal. 2007;17(1):6–10. doi: 10.5737/1181912x171610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro CM, Lee KA, Bliwise DL, Urizar GG, Woodward SH, King AC. Sleep patterns and sleep-related factors between caregiving and non-caregiving women. Behavioral Sleep Medicine. 2009;7:164–179. doi: 10.1080/15402000902976713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cella DF, Jacobsen PB, Orav EJ, Holland JC, Silberfarb PM, Rafla S. A brief POMS measure of distress for cancer patients. Journal of Chronic Diseases. 1987;40:939–942. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90143-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandana SR, Movva S, Arora M, Singh T. Primary brain tumors in adults. American Family Physician. 2008;77:1423–1430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung YB, Liu KY, Yip PS. Performance of the CES-D and its short forms in screening suicidality and hopelessness in the community. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2007;37(1):79–88. doi: 10.1521/suli.2007.37.1.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole CS, Richards KC. Sleep and cognition in people with Alzheimer’s disease. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2005;26:687–698. doi: 10.1080/01612840591008258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creese J, Bédard M, Brazil K, Chambers L. Sleep disturbances in spousal caregivers of individuals with Alzheimer’s disease. International Psychogeriatrics. 2008;20:149–161. doi: 10.1017/S1041610207005339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran SL, Andrykowski MA, Studts JL. Short form of the Profile of Mood States (POMS-SF): Psychometric information. Psychological Assessment. 1995;7:80–83. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.7.1.80. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dinges DF, Rogers NL, Baynard MD. Chronic sleep deprivation. In: Kryger MH, Roth T, Dement WC, editors. Principles and practices of sleep medicine. 5. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2011. pp. 67–75. [Google Scholar]

- Fonareva I, Amen AM, Zajdel DP, Ellingson RM, Oken BS. Assessing sleep architecture in dementia caregivers at home using an ambulatory polysomnographic system. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology. 2011;24:50–59. doi: 10.1177/0891988710397548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grutsch JF, Wood PA, Du-Quiton J, Reynolds JL, Lis CG, Levin RD, Hrushesky WJ. Validation of actigraphy to assess circadian organization and sleep quality in patients with advanced lung cancer. Journal of Circadian Rhythms. 2011;9:4. doi: 10.1186/1740-3391-9-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton NA, Nelson CA, Stevens N, Kitzman H. Sleep and psychological well-being. Social Indicators Research. 2007;82:147–163. doi: 10.1007/s11205-006-9030-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karnofsky DA, Abelmann WH, Craver LF, Burchenal JH. The use of the nitrogen mustards in the palliative treatment of carcinoma. Cancer. 1948;1:634–656. 10.1002/1097-0142(194811) 1:4<634::AID-CNCR2820010410 >3.0.CO;2-L. [Google Scholar]

- Keir ST, Guill AB, Carter KE, Boole LC, Gonzales L, Friedman HS. Differential levels of stress in caregivers of brain tumor patients—Observations from a pilot study. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2006;14:1258–1261. doi: 10.1007/s00520-006-0090-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochar J, Fredman L, Stone KL, Cauley JA. Sleep problems in elderly women caregivers depend on the level of depressive symptoms: Results of the Caregiver—Study of Osteoporotic Fractures. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2007;55:2003–2009. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01434.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KA. Impaired sleep. In: Carrieri-Kohlman V, Lindsey AM, West CM, editors. Pathophysiological phenomena in nursing: Human responses to illness. St. Louis, MO: Saunders; 2003. pp. 363–385. [Google Scholar]

- Lee KA, Landis C, Chasens ER, Dowling G, Merritt S, Parker KP, Weaver TE. Sleep and chronobiology: Recommendations for nursing education. Nursing Outlook. 2004;52:126–133. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2003.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens MP, Parker JC, Smarr KL, Hewett JE, Ge B, Slaughter JR, Walker SE. Development of a shortened Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression scale for assessment of depression in rheumatoid arthritis. Rehabilitation Psychology. 2006;51:135–139. doi: 10.1037/0090-5550.51.2.135. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mastin DF, Bryson J, Corwyn R. Assessment of sleep hygiene using the Sleep Hygiene Index. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2006;29:223–227. doi: 10.1007/s10865-006-9047-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayers AG, Grabau EA, Campbell C, Baldwin DS. Subjective sleep, depression and anxiety: Inter-relationships in a non-clinical sample. Human Psychopharmacology. 2009;24:495–501. doi: 10.1002/hup.1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCurry SM, Logsdon RG, Teri L, Vitiello MV. Sleep disturbances in caregivers of persons with dementia: Contributing factors and treatment implications. Sleep Medicine Reviews. 2007;11:143–153. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2006.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNair DM, Lorr M, Droppleman LF. EITS manual for the Profile of Mood States. San Diego, CA: Educational and Industrial Testing Service; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Moldofsky H. Sleep and the immune system. International Journal of Immunopharmacology. 1995;17:649–654. doi: 10.1016/0192-0561(95)00051-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monti JM, Monti D. Sleep disturbance in generalized anxiety disorder and its treatment. Sleep Medicine Reviews. 2000;4:263–276. doi: 10.1053/smrv.1999.0096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgenthaler T, Alessi C, Friedman L, Owens J, Kapur V, Boehlecke B, Swick TJ. Practice parameters for the use of actigraphy in the assessment of sleep and sleep disorders: An update for 2007. Sleep. 2007;30:519–529. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.4.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz C, Juarez G, Muñoz ML, Portnow J, Fineman I, Badie B, Ferrell B. The quality of life of patients with malignant gliomas and their caregivers. Social Work in Health Care. 2008;47:455–478. doi: 10.1080/00981380802232396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omay SB, Vogelbaum MA. Current concepts and newer developments in the treatment of malignant gliomas. Indian Journal of Cancer. 2009;46:88–95. doi: 10.4103/0019-509X.49146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papadimitriou GN, Linkowski P. Sleep disturbance in anxiety disorders. International Review of Psychiatry. 2005;17:229–236. doi: 10.1080/0950260500104524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrin PB, Heesacker M, Stidham BS, Rittman MR, Gonzalez-Rothi LJ. Structural equation modeling of the relationship between caregiver psychosocial variables and functioning of individuals with stroke. Rehabilitation Psychology. 2008;53:54–62. doi: 10.1037/0090-5550.53.1.54. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qidwai W, Baqir M, Baqir SM, Zehra S. Knowledge, attitude, and practices regarding sleep and sleep hygiene among patients presenting to outpatient and emergency room services at a teaching hospital in Karachi. Pakistan Journal of Medical Sciences. 2010;26:629–633. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe MA, Kairalla JA, McCrae CS. Sleep in dementia caregivers and the effect of a nighttime monitoring system. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2010;42:338–347. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2010.01337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe MA, McCrae CS, Campbell JM, Benito AP, Cheng J. Sleep pattern differences between older adult dementia caregivers and older adult noncaregivers using objective and subjective measures. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 2008;4:362–369. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salander P, Spetz A. How do patients and spouses deal with the serious facts of malignant glioma? Palliative Medicine. 2002;16:305–313. doi: 10.1191/0269216302pm569oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmer C, Ward-Smith P, Latham S, Salacz M. When a family member has a malignant brain tumor: The caregiver perspective. Journal of Neuroscience Nursing. 2008;40(2):78–84. doi: 10.1097/01376517-200804000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnell O, Tonn J. Unmet medical needs in glioblastoma management and optimal sequencing of the emerging treatment options. European Journal of Clinical and Medical Oncology. 2009;1(2):41–49. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz R, Beach SR. Caregiving as a risk factor for mortality: The Caregiver Health Effects Study. JAMA. 1999;282:2215–2219. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.23.2215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shacham S. A shortened version of the Profile of Mood States. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1983;47:305–306. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4703_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherwood PR, Given BA, Doorenbos AZ, Given CW. Forgotten voices: Lessons from bereaved caregivers of persons with a brain tumour. International Journal of Palliative Nursing. 2004;10:67–75. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2004.10.2.12460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherwood PR, Given BA, Given CW, Schiffman RF, Murman DL, Lovely M, Remer S. Predictors of distress in caregivers of persons with a primary malignant brain tumor. Research in Nursing and Health. 2006;29:105–120. doi: 10.1002/nur.20116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherwood PR, Given BA, Given CW, Schiffman RF, Murman DL, von Eye A, Remer S. The influence of caregiver mastery on depressive symptoms. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2007;39:249–255. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2007.00176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmonds MJ. Physical function in patients with cancer: Psychometric characteristics and clinical usefulness of a physical performance test battery. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2002;24:404–414. doi: 10.1016/S0885-3924(02)00502-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein MB, Mellman TA. Anxiety disorders. In: Kryger MH, Roth T, Dement WC, editors. Principles and practice of sleep medicine. 5. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2011. pp. 1297–1310. [Google Scholar]

- Stepanski EJ, Wyatt JK. Use of sleep hygiene in the treatment of insomnia. Sleep Medicine Reviews. 2003;7:215–255. doi: 10.1053/smrv.2001.0246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunseri M, Liden CB, Farringdon J, Pelletier R, Safier S, Stivoric J, Vishnubhatla S. The SenseWear Armband as a sleep detection device. 2009 Retrieved from http://www.bodymedia.com/Professionals/Whitepapers/The-SenseWear-armband-as-a-Sleep-Detection-Device.

- Van Dongen HPA, Rogers NL, Dinges DF. Sleep debt: Theoretical and empirical issues. Sleep and Biological Rhythms. 2003;1:5–13. [Google Scholar]

- Vaz Fragoso CA, Gill TM. Sleep complaints in community-living older persons: A multifactorial geriatric syndrome. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2007;55:1853–1866. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01399.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Känel R, Dimsdale JE, Ancoli-Israel S, Mills PJ, Patterson TL, McKibbin CL, Grant I. Poor sleep is associated with higher plasma proinflammatory cytokine interleukin-6 and procoagulant marker fibrin D-dimer in older caregivers of people with Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2006;54:431–437. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00642.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wideheim AK, Edvardsson T, Påhlson A, Ahlström G. A family’s perspective on living with a highly malignant brain tumor. Cancer Nursing. 2002;25:236–244. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200206000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yates JW, Chalmer B, McKegney FP. Evaluation of patients with advanced cancer using the Karnofsky Performance Status. Cancer. 1980;45:2220–2224. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19800415)45:8<2220::aid-cncr2820450835>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]