Abstract

African American young women exhibit higher risk for sexually transmitted infections, including HIV/AIDS, compared with European American women, and this is particularly true for African American women living in low-income contexts. We used rigorous qualitative methods, that is, domain analysis, including free listing (n = 20), similarity assessment (n = 25), and focus groups (four groups), to elicit self-described motivations for sex among low-income African American young women (19-22 years). Analyses revealed six clusters: Love/Feelings, For Fun, Curiosity, Pressured, For Money, and For Material Things. Focus groups explored how African American women interpreted the clusters in light of condom use expectations. Participants expressed the importance of using condoms in risky situations, yet endorsed condom use during casual sexual encounters less than half the time. This study highlights the need for more effective intervention strategies to increase condom use expectations among low-income African American women, particularly in casual relationships where perceived risk is already high.

Keywords: African American, HIV/AIDS, qualitative methods, sex behavior, women’s health

African American young women exhibit dramatically higher rates of sexually transmitted infections (STIs), including HIV/AIDS, compared with their European American counterparts (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2009). Women in low-income communities are at particularly high risk. Motivational constructs play an important role in health behavior change theories (Fisher, Fisher, Bryan, & Misovich, 2002); yet scarce qualitative research has been conducted with African American young women to understand their motivations to engage in sex and use condoms. The frameworks that guide sexual health research are often inapplicable within specific ethnic–gender groups given variation in norms and sexual beliefs (Deardorff, Tschann, & Flores, 2008). Moreover, survey research often fails to address peer influences, which contribute to sexual behaviors (Harper, Gannon, Watson, Catania, & Dolcini, 2004). Individuals hold shared concepts of motivations, which allow them to anticipate and interpret others’ behaviors (D’Andrade & Strauss, 1992). These encompass knowledge and perceptions imparted by social learning. In the current study, domain analysis (DA) was conducted to elicit self-described sexual motivations, followed by focus groups to determine whether these motivations were associated with condom use expectations. By encouraging women to “speak for themselves” (Moore & Rosenthal, 1992), this formative study aimed to generate a deeper understanding of sexual motivations that may be socially sanctioned and bolstered within peer groups and subsequently influence condom use. This approach may inform prevention efforts with young low-income African Americans.

Method

Participants and Procedures

Participants were African American women, 19 to 22 years old, living in a low-income urban neighborhood. Three research phases were conducted, and the following sampling methods were used: Phase 1—Free Listing, convenience sampling; Phase 2—Pile Sort Similarity Assessment, venue sampling (MacKellar, Valleroy, Karon, Lemp, & Janssen, 1996); Phase 3—Focus Groups (FGs), convenience sampling. Phase 1 and Phase 2 participants received $25. FG participants received $50. Interviewers were African American women. The university’s institutional review board approved this research.

Domain analysis is a method that describes aspects of beliefs among members of a social group (Bernard, 1994; Weller, 1984). DA allows participants to express their ideas freely and determines how these ideas are organized. DA involves two phases of data collection: free listing and pile sort similarity assessment. Here, these procedures elicited self-described “motivations for sex.” We added a third phase, FGs, to determine whether the motivation clusters from the DA were associated with condom use expectations.

Phase 1: Free listing

In individual interviews, participants (n = 20) listed answers to one question: “What are some reasons to have sex with somebody?” Responses were recorded. When the participant stopped giving responses, the interviewer read back the four most recent responses and the question was repeated. This was repeated until there were no new responses.

Phase 2: Pile sort similarity assessment

Free listing concepts mentioned by two or more participants in Phase 1 were included in a list of 39 sort items, which were then presented to a different sample of participants (n = 25) to elicit similarity assessments using a pile sort procedure (Borgatti & Halgrin, 1999). Participants were given randomly shuffled cards and asked to “sort the cards and place the cards together that you think belong together.”

Phase 3: Focus groups

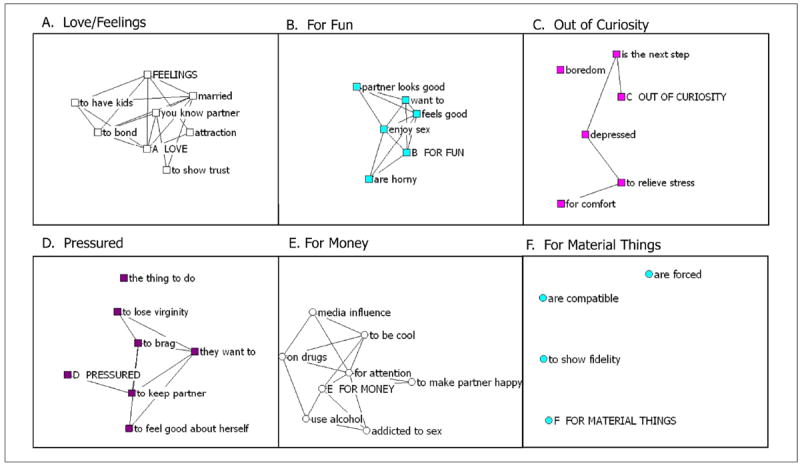

Four FGs (n = 3-13 women each) were presented with projected images of the six similarity assessment groupings (clusters) without labels (see Figure 1). Women were asked, “Why would someone your age put these reasons to have sex together?” and then, “What kind of woman would have sex for these reasons?” Following discussion, participants were asked, “Think about women who have sex for these reasons. What percentage of these women would use a condom?” Participants responded using a scale from 0 to 100.

Figure 1.

Individual tabu search–identified clusters of women’s reasons for sex pile sort data (A-F) from graphical layout algorithm (Phase 2, n = 21)

Note. Highest frequency item for each cluster is in uppercase letters. A line between items indicates items that are deemed similar by at least 50% of respondents. Free listing frequencies for items are available on request.

Analysis

Phase 1: Free listing analysis

Free listing responses were grouped according to specific literal meaning by two coders working separately. Complex responses were double coded. A spreadsheet of grouped and labeled items was prepared, with differences resolved by the last author. The number of responses in each group was totaled, and a frequency table of the groupings was constructed to prepare cards for pile sorting.

Phase 2: Cluster analysis

An item-by-item aggregate proximity matrix was generated from the pile sort data (pile sort procedure in Anthropac 4.0 software; Borgatti, 1996). Visual representations of matrices were graphed using graph layout algorithms (GLAs). The data matrix was dichotomized to create a network and then path distances were computed and used to position points (Borgatti & Halgrin, 1999). To assist in the interpretation of the aggregate data matrix, cluster analysis using Anthropac 4.0 tabu search was used (Borgatti, 1996). A cultural domain was defined as a network of items semantically related by linked meanings. Four researchers independently identified primary dimensions and then discussed these until consensus was reached. A primary dimension indicates how the positioning on the GLA plot distinguishes items and gives them unique meanings (Borgatti & Halgrin, 1999).

Phase 3: FG analysis

Content-focused techniques were applied to identify codes across FGs. Two secondary coders established an intercoder reliability of 87%. To determine whether condom use expectations scores differed across motivation clusters, we used multivariate analyses and custom contrasts.

Results

Participants from Phase 2 were 20.4 years (SD = 1.4) and had 1.12 (SD = 0.8) sexual partners in the past month. Sixty-eight percent had a main partner, and 18% reported infidelity in the past month. Forty-two percent reported “never” using a condom with a main partner, and 80% reported “always” using a condom with a nonmain partner.

Free Listing and Cluster Analyses

Graph layout algorithm plot results indicated that the primary dimension was “motivations for having sex,” which varied from based on a bond or attraction to based on external factors. Tabu cluster results showed six clusters (Figure 1); labels were determined by the highest frequency item.

Focus Groups

Clusters A and B represent motivations for sex based on a bond or attraction; C and D represent mixed motivations; E and F represent motivations based on external factors. Representative FG quotes are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Representative Quotations From Four Focus Groups

| A-1 | Sex is really sacred, whether you’re a virgin or not. Because some people can abuse sex, like … bops and rips and all that … But this is somebody that knows they value sex in a positive way. Like, I wanna have sex with this person because I could see us being in a relationship and I could see us having kids and I could see us getting married. |

| A-2 | You can’t trust every man you sleep with. Period … Just because he’s sweet to you, just because he shows you one thing you just can’t trust him enough to wanna build, to have a kid with him because that would be meaning having sex unprotectedly and if I dunno if he’s really just with me. |

| B-1 | A party girl … is standing right at the bar with her drinks, with two, one dude right here, another dude over here. They askin her, “Can I buy you a drink?” She choosin, “Oh is this fun. Oh he’s cuter, so I’ma talk to him. Oh I got lil drinks, I’m horny, lemme go home with him.” |

| B-2 | I mean, if you’re young and you don’t have no kids or you don’t have no responsibilities … you’re going to school … you’re functioning, and you’re doing these things because it feel good to you, you having fun, you’re horny. I mean, that’s … sex is a part of life. You need to be satisfied, so if you feel this way, go ahead. Just be safe. |

| B-3 | After you just been having sex for so long, and it’s just for fun, other things is going to start go come with that. Just having sex for fun it’s gonna turn into, “Oh, dang I accidentally got pregnant, or I accidentally got burnt, or oh I seen him with somebody else. He got a wife or he’s gotta girlfriend and it’s emotion.” It seems like it’s just, if you have sex for those reasons only, you’re opening the door for other things to come in. You’re obviously not searching for love and if you’re having sex for fun and your partner knows that it’s just for fun, how much can they respect you? How long will it be for fun? |

| C-1 | This would seem like somebody at the beginning phase of going to have sex. Starting to have sex and accepting who you are and what it is you want. Like, “Oh, I’m doing it because they said.” |

| C-2 | I have a partner I’m with and I’ve been with a very long time, and whenever I’m sad, I wanna cuddle, or whenever I’m mad, I wanna cuddle. I wanted to be comforted and it always leads to that chemical release. That comforts me. And I mean you don’t necessarily have to be in relationship to have sex for these reasons. |

| D-1 | I think [the items] are put together because of the social group basically. Do things based on other peoples, pressure, or basically to make yourself feel like everybody else. The person is the type who will follow older kids but not ask them why they are doing things. |

| D-2 | Not having a male figure in your life is one of the reasons why little girls go about having sex. I got a lot of friends that didn’t grow up with a father and they’re out there having sex and a hankering for boys to have a male figure in their life to say, “I love you,” “You look pretty.” |

| E-1 | You’re gonna have sex because you want to or you’re going to have sex with that right person cuz you feel like that person’s right for you to be doin it. Not because, “Oh I ain’t got no money so I know the only way I can get some money is if I turn dates and do tricks n all of that.” |

| E-2 | If they’ve been raped, if their trust has constantly been abused, their thoughts, their actions, the things they do, are completely different. They have sex for money, and the drugs and all those things and they actually feel better doing it because it’s more attention and more joy coming from it so they don’t see no wrong in it. |

| F-1 | Why should I take care of somebody else? If you grown, I’m sorry, no I feel like a man should be able to take care of me. My man should be my protector. My man supposed to be my builder. Like, if you not trying to do nothing, why should I date you? |

Cluster A (Love/Feelings)

Topics were (a) good things about a primary relationship, (b) bad things about a primary relationship, and (c) maturity. Participants saw a woman wanting to make a future, have one partner, get emotionally attached, and trust her partner (Table 1, A-1). Although being in a primary relationship was generally associated with high self-esteem, some participants reacted negatively, saying, “I hate that” or “I’m through with that.” Key issues were sexual betrayal and STI risk (A-2).

Cluster B (For Fun)

Topics were (a) promiscuity, (b) caution, and (c) enjoying sex. This cluster was described as a “party girl” who has sex for pleasure but not love. She is attracted by appearance (B-1). Cluster B appealed to young, uncommitted participants. Some questioned the dominant perception of this cluster as promiscuous (B-2). Others voiced objections because of risks, for example, emotional harm (B-3).

Cluster C (Out of Curiosity)

Topics included (a) immaturity and (b) relief. The person represented was seen as a virgin, lacking awareness (C-1). A second topic was sex providing relief from depression/stress (C-2). This topic of relief often intersected with immaturity, implying that sexual novices have sex to obtain comfort at times of insecurity.

Cluster D (Pressured)

Topics were (a) inexperience, (b) control by sexual partners and peers, and (c) absent fathers. This cluster was described as young, immature, naive, someone who satisfies others’ interests before her own and is easily controlled (D-1). Participants suggested this person was abused or lacked a male figure (D-2).

Cluster E (For Money)

Topics were (a) “prostitution,” (b) strong desire for sex, (c) “hype” behind sex, and (d) sexual abuse. This person was perceived as someone who exchanges money or drugs for sex or is “addicted to sex.” Negative judgments were expressed (E-1). Others saw sex in this cluster as a way of fending off loneliness but discussed HIV/STI risk. Participants saw this person as influenced by media and peer “hype” around sex. Some felt that this person had experienced sexual abuse (E-2).

Cluster F (For Material Things)

Topics were (a) having “sugar daddies,” (b) receiving male financial support, and (c) control/force. Participants described “gold diggers” who are attracted to money, cars, and jewelry. One participant said that her friends have “sugar daddies”: older men who provide gifts or money in return for sex. Women expected sexual partners to provide for them and take care of themselves (F-1).

Condom Use Expectations

Cluster B (For Fun) was associated with the highest condom use expectations (47.6%), which was higher than Cluster C—34.11%; t(27) = 2.11, p < .044, 95% confidence interval (CI) = [0.9, 26.2]; Cluster D—30.73%; t(27) = 2.32, p < .028, 95% CI = [2.6, 31.2]; and Cluster F—36.51%; t(27) = 2.19, p < .038, 95% CI = [1.2, 21.2]. There were no other differences.

Discussion

We used rigorous qualitative methods to understand how young African American women characterized their motivations for sex. These methods allowed for individual expression (pile sort) as well as elaboration within a group setting (FGs). By including FGs, we ensured that interpretations of motivation clusters were grounded in women’s belief systems.

The bond/attraction clusters identified were consistent with past quantitative research showing love, feelings, and fun as top reasons reported by African American young women for having sex (Ozer, Dolcini, & Harper, 2003). Love/Feelings was associated with long-term relationships, intentions to have children, marriage, and trust. Past qualitative research suggests that sexual relationships characterized by love are linked to parenthood desires, which have clear implications for condom use (Eyre & Millstein, 1999). Conversely, For Fun encompassed sex for immediate gratification. FG discussions evinced nuanced and conflicting responses. Whereas some participants found Love/Feelings desirable, others emphasized risks associated with committed partners, including infidelity. Similarly, although participants acknowledged the appeal of casual sex (For Fun), they also discussed associated risks. Such discussions likely reflect natural discordance within young women’s peer groups. Interventions should address the complexity of sexual decision making, given social norms and inherent contradictions.

The two clusters that focused on external factors evoked opposing emotional reactions. Participants responded negatively to sex For Money, describing these women as psychologically damaged or prostitutes. Conversely, some women described socially acceptable expectations of material gain (For Material Things) within sexual relationships. Such nuances provide information about social norms that could inform interventions, particularly as different types of material exchange may confer varying levels of sexual risk.

Two clusters (Curiosity and Pressured) showed no dominant bond/attraction or external motivation themes but were linked to low self-esteem and/or naïveté. Although the Curiosity cluster was labeled as such because of its highest frequency item from the pile sort procedure, FG discussions focused predominantly on immaturity and stress relief, and participants generally viewed these as negative. Similarly, the Pressured cluster was perceived to result from inexperience or past trauma. Quantitative research shows that pressure from others is not a primary reason for having sex among African American females (Ozer et al., 2003). Despite viewing these two clusters as undesirable, participants exhibited empathy for women depicted in them and described their own maturational processes to overcome similar characteristics. Such narratives suggest that interventions should address processes related to self-esteem and coping to promote healthier sexual behaviors.

Condom use expectations were low (<50%) across all clusters. Only one cluster, For Fun, was risky enough to trigger higher condom use expectations. Other factors besides risk perception may lead to low expectations. Past qualitative research indicates that masculinity ideologies (Fasula, Miller, & Wiener, 2007) that promote partner concurrency (Bowleg et al., 2011) and low expectations of partner fidelity (Harper et al., 2004) may influence African American women’s condom use expectations.

This research was exploratory and limited to a small sample of urban low-income women, thus limiting generalizability. However, given the high STI/HIV risk in this population, findings have important implications within this group. Participants were not asked to elaborate on “why” they scored the condom use expectations for each motivation cluster as they did. This represents an important area for future research.

Findings highlight the need for tailored interventions to increase condom use in casual relationships, where perceived risk is already high, and in primary relationships, where motivations for condom use may be low. Interventions that address mediators of sexual risk, including self-esteem and coping, may be more effective than those focusing solely on risk perceptions.

Acknowledgments

The project described was supported by Award Number R01HD051438 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development or the National Institutes of Health. We thank community agencies in the San Francisco Bay Area, CA, that generously enabled us to access young adults, and we thank the young adults who participated. We also extend our appreciation to Donald Crisp and Benita Jacque who conducted the interviews.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Bernard HR. Research methods in anthropology: Qualitative and quantitative approaches. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Borgatti SP. Anthropac (Version 4.0) [Computer software] Natick, MA: Analytic Technologies; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Borgatti SP, Halgrin DS. Mapping culture: Freelists, pilesorting, tiads and consensus analysis. In: Schensul J, LeCompte M, editors. The ethnographer’s toolkit: Vol 3 Enhanced ethnographic methods. Walnut Creek, CA: Altamira Press; 1999. pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg L, Teti M, Massie JS, Patel A, Malebranche DJ, Tschann JM. What does it take to be a man? What is a real man?”: Ideologies of masculinity and HIV sexual risk among Black heterosexual men. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2011;13:545–559. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2011.556201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexual and reproductive health of persons aged 10-24 years-United States, 2002-2007. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report Surveillance Summaries. 2009;58(6):1–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Andrade RG, Strauss C. Human motives and cultural models. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Deardorff J, Tschann JM, Flores E. Sexual values among Latino youth: Measurement development using a culturally based approach. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2008;14:138–146. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.14.2.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyre SL, Millstein SG. What leads to sex? Adolescent preferred partners and reasons for sex. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 1999;9:277–307. doi: 10.1207/s15327795jra0903_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fasula AM, Miller KS, Wiener J. The sexual double standard in African American adolescent women’s sexual risk reduction socialization. Women & Health. 2007;46(2-3):3–21. doi: 10.1300/J013v46n02_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher JD, Fisher WA, Bryan A, Misovich SJ. Information-motivation-behavioral skills model-based HIV risk behavior change intervention for inner-city high school youth. Health Psychology. 2002;21:177–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper GW, Gannon C, Watson SE, Catania JA, Dolcini MM. The role of close friends in African American adolescents’ dating and sexual behavior. Journal of Sex Research. 2004;41:351–362. doi: 10.1080/00224490409552242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKellar D, Valleroy L, Karon J, Lemp G, Janssen R. The young men’s survey: Methods for estimating HIV seroprevalence and risk factors among young men who have sex with men. Public Health Reports. 1996;111:138–144. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore SM, Rosenthal DA. Australian adolescents’ perceptions of health-related risks. Journal of Adolescent Research. 1992;7:177–191. [Google Scholar]

- Ozer EJ, Dolcini MM, Harper GW. Adolescents’ reasons for having sex: Gender differences. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2003;33:317–319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weller SC. Consistency and consensus among informants: Disease concepts in a rural Mexican village. American Anthropologist. 1984;86:966–975. [Google Scholar]