Abstract

As a specific variation of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting, anticipatory nausea and vomiting (ANV) appears particularly linked to psychological processes. The three predominant factors related to ANV are classical conditioning; demographic and treatment-related factors; and anxiety or negative expectancies. Laboratory models have provided some support for these underlying mechanisms for ANV. ANV may be treated with medical or pharmacological interventions, including benzodiazepines and other psychotropic medications. However, behavioral treatments, including systematic desensitization, remain first line options for addressing ANV. Some complementary treatment approaches have shown promise in reducing ANV symptoms. Additional research into these approaches is needed. This review will address the underlying models of ANV and provide a discussion of these various treatment options.

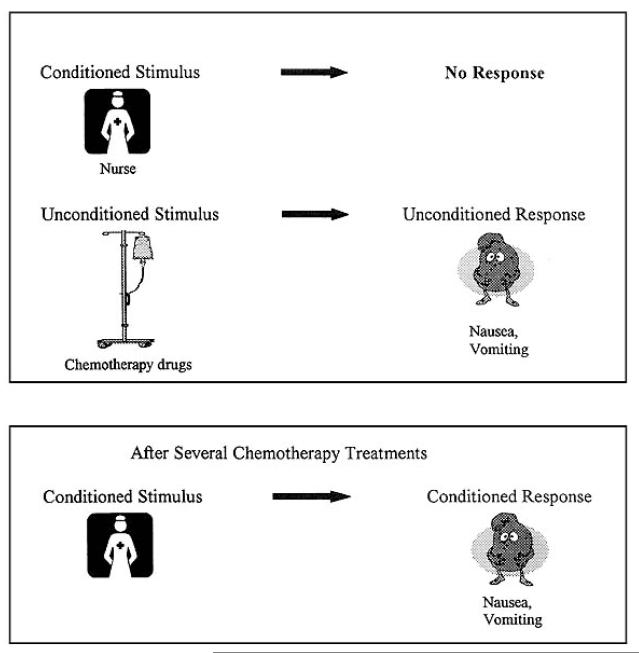

Anticipatory nausea and vomiting (ANV) is a common complaint among cancer patients and is often predicated on the development of chemotherapy-induced nausea or vomiting. Acute or delayed nausea following chemotherapy infusion, known as chemotherapy-induced nausea (CINV) is a common side effect of treatment. However, up to 20% of patients report experiencing nausea before any one chemotherapy cycle, and up to 30% report this anticipatory, learned, or psychological nausea by the fourth chemotherapy cycle (Morrow & Roscoe, 1997). Repeated exposure to chemotherapy increases risk for the development of ANV. It appears, therefore, that development of ANV conforms to a classical conditioning model, wherein repeated pairings of unconditioned (i.e., chemotherapy) and conditioned (e.g., the clinic, the nurse) stimuli produce nausea and vomiting even before administration of emetogenic agents. We discuss this model below, along with other psychological factors that may contribute to development of ANV and laboratory validation of these models.

ANV is typically unresponsive to treatment with antiemetic pharmaceuticals. Given its psychological and behavioral basis, psychotropic medications may prove a more effective method of pharmaceutical intervention. Behavioral treatment, however, remains the most effective option for addressing ANV. We discuss these therapeutic modalities below, along with a discussion of emerging complementary and alternative therapies.

1. Psychological Models of ANV

Psychological mechanisms and demographic factors contribute to the onset, frequency, severity, and duration of ANV. Three distinct but interrelated factors contributing to ANV are: 1) classical conditioning, which may lead to anticipatory nausea; 2) demographic, clinical, and treatment-related factors, which can predict risk to anticipatory nausea; and 3) anxiety or negative expectancies, which may prompt and increase sensitivity to anticipatory nausea.

1.1. Classical Conditioning and ANV

The National Cancer Institute has cited Pavlovian classical conditioning as the theoretical mechanism best able to explain the genesis of ANV (National Cancer Institute, 2012). In the classical conditioning model of ANV, an unconditioned stimulus (chemotherapy) that naturally produces an unconditioned response (nausea) is paired with a conditioned stimulus. Potential conditioned stimuli in the context of ANV can include the sights and smells of the clinic, the nurses, the treatment room, etc. After repeated pairings of the unconditioned stimulus with this conditioned stimulus, exposure to the conditioned stimulus alone is sufficient to elicit the conditioned response (nausea; Matteson, Roscoe, Hickok, & Morrow, 2002; Roscoe, Morrow, Aapro, Molassiotis, & Olver, 2011; Stockhorst, Enck, & Klosterhalfen, 2007a). See Figure 1 for a graphical representation of this process. The cancer patient’s nausea is anticipatory, as it may begin even before administration of the chemotherapeutic agent. The conditioned nature of ANV is supported by the finding that rates and severity of ANV tend to increase after repeated chemotherapy cycles (Stockhorst et al., 2007a); that is, after repeated pairings of the unconditioned and conditioned stimuli.

Figure 1.

Graphical representation of the development of ANV

1.2. Demographic Factors and ANV

Certain personal characteristics and events related to cancer treatment appear to increase the likelihood that a patient will experience ANV. Variables cited by the National Cancer Institute as being correlated with ANV are listed in Table 1. In addition to the emetogenic potential of the chemotherapeutic agent, an age under 50 and female gender are the most common indicators of CINV and ANV (NCI, 2012; Roscoe, Morrow, & Hickok, 1998; Roscoe et al., 2011). Other common factors correlated with ANV include susceptibly to motion sickness, emetogenic potential of chemotherapy agents, weakness, dizziness, or lightheadedness after chemotherapy, morning sickness during pregnancy, and nausea and vomiting after last chemotherapy session.

Table 1. Demographic and treatment related factors correlated with ANV.

|

1.3. New Vistas in Understanding Psychological Mechanisms of ANV: Negative Expectancies

In addition to demographic and clinical variables that contribute to ANV, psychological, cognitive, and social factors contribute to the conditioned response of ANV. For example,anxiety, self-absorption, and response expectancies have all been shown to be involved in ANV development (Montgomery et al., 1998; Morrow et al., 1998; Watson, 1993). Anxiety may affect the development of ANV at least in part through negative expectancies (Andykowski, 1990; Watson, McCarron, & Law, 1992), as expectancies affect development of other learning-based conditioning effects (Kirsch, 1997).

Current research on behavioral contributions relating to ANV focus on patients’ beliefs regarding symptom development. In the patient belief model of ANV development, healthcare professionals impart information about treatment side effects while listening and responding to patients’ fears and hopes. Patient and caregiver communication is crucial in the development of patients’ expectancies for treatment outcomes, termed “response expectancies,” which can influence physical, emotional and mental outcomes throughout the treatment process (Colagiuri, Roscoe, Morrow, et al., 2008). In a classic work on this topic, Kirsch (1985) suggests that anticipation or response expectancy for the occurrence of a physiological sensation (e.g., nausea) can generate corresponding subjective experiences and directly affect both physiological and psychological outcomes.

The effect of response expectancies can be considerable, and these expectancies account for variance in ANV above and beyond the emetogenicity of the chemotherapeutic agent and other known predictive factors for nausea such as gender and age (Colagiuri et al., 2008; Roscoe, Morrow, Colagiuri, et al., 2010; Roscoe, O’Neill, Jean-Pierre, et al., 2010). For example, Roscoe et al studied 194 breast cancer patients about to begin chemotherapy with a doxorubicin-based regimen and found that patients who believed that they were “very likely” to experience severe nausea were five times more likely to experience severe nausea than those who believed that they were “very unlikely” to do so (Roscoe, Bushunow, Morrow, et al., 2004).

Although expectancies may represent an acknowledgement of one’s propensity to develop nausea based on past experience (e.g., nausea during pregnancy or susceptibility to motion sickness), these expectancies are also influenced by socio-cultural factors and what patients are told to expect from the range of information they receive from clinicians, hospital staff, other patients, family, friends, and the world at large. Thus, nausea expectancies can be considered to have both internal and external sources, and it is these external sources that might provide a way to reduce chemotherapy-induced nausea. Unlike other risk factors for nausea, nausea expectancies are malleable and provide an opportunity for intervention.

A comprehensive review of the expectancy literature was undertaken by the British National Coordinating Centre for Health Technology Assessment. These authors screened 47,600 references for their relevancy and quality and chose the 93 highest-quality studies for their review. They reported that expectancies play an important role in symptom and side-effect development and further concluded that response expectancies constitute a central underlying mechanism of placebo effect (Crow, Gage, Hampson, et al., 1999). Similarly, the nocebo hypothesis, discussed by Hahn (1997) and Barsky et al. (2002), proposes that expectations of developing side effects can cause symptoms to appear. It is also likely that studies that have linked anxiety to the development of nausea are, to some extent, capturing the construct of negative expectancies (Roscoe, Jean-Pierre, Shelke, et al., 2006).

In sum, screening patients for the demographic, clinical, and psychological variables discussed above and for other cognitive/emotional vulnerabilities may help providers to identify patients likely to develop ANV. At present, there remains a need to develop a succinct and comprehensive screening process for risk factors related to ANV and to integrate such a process into cancer center treatment evaluations.

2. Laboratory Models of ANV

Though the etiology of ANV is best understood as a form of classical Pavlovian conditioning (Neese, Carli, Curtin, & Kleinman, 1980; Stockhorst, Klosterhalfen, Klosterhalfen, & al., 1993), which is assumed to occur within the central nervous system (Ramsay & Woods, 1997), development of ANV is likely due in part to poor initial control of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV; Morrow, Roscoe, Kirshner, Hynes, & Rosenbluth, 1998). Given the link between ANV and CINV, a word about the etiology of CINV is appropriate.

2.1. Models linking ANV to CINV

The mechanism of CINV due to chemotherapeutic agents does not depend on a unique area but involves a complex network of neuroanatomical and peripheral centers as well as neurotransmitters and receptors. The central and peripheral regions include a) the emetic or vomiting center (VC), which is a cluster of neurons in the medulla oblongata and is the primary structure for coordinating nausea and vomiting; b) the chemoreceptor trigger zone (CTZ) in the area postrema located at the floor of the fourth ventricle of the brain; c) the vagal nerve afferents which project from the gastrointestinal (GI) tract to the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS) and the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus; and d) the Enterochromaffin cells (EC) lining the GI tract (Darmani & Ray, 2009; Feyer & Jordan, 2011; Hornby, 2001; Rubenstein, Slusher, Rojas, & Navari, 2006). In general, chemotherapeutic agents can cause emesis through afferent input at a number of different sites, involving different mechanisms. Chemotherapeutic agents are toxic to ECs lining the GI mucosa and stimulate them to release neurotransmitters, such as dopamine, serotonin (5-HT), substance P (SP), acetylcholine, histamine, and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) (Hesketh, 2008; Leslie & Reynolds, 1993; Navari, 2009; Rudd & Andrews, 2005). These neurotransmitters bind to the appropriate receptors on the abdominal vagal afferents (Blackshaw, Brookes, Grundy, & Schemann, 2007; Burke, Mason, Surman, & al., 2011; Lesurtel, Soll, Graf, & Clavien, 2008), hence activating them, which then conduct the stimuli to the dorsal vagal complex consisting of emetic/VC, the area postrema (CTZ) and the NTS. These sensory inputs are then integrated resulting in the activation of the emetic response (Hesketh, 2008). Another possible source of afferent input inducing emesis involves the CTZ (Borison, 1989; Miller & Leslie, 1994), which is sensitive to chemical stimuli from drugs (Rang, Dale, Ritter, & Flower, 2007). The blood-brain barrier located in CTZ is permeable to circulating mediators, thereby, allowing them to directly interact with the VC (Rang et al., 2007) and resulting in emesis.

Studies have reported that no single neurotransmitter appears to be responsible for all CINV (Grunberg & Ireland, 2005), let alone for ANV. In addition, though the inhibition of some of these pathways results in reducing vomiting, the same is not true for reducing nausea. This suggests that the induction of nausea and vomiting may involve different pathways and mediators. Moreover, post-treatment CINV occurs due to stimuli to the CTZ and the VC regions while ANV occurs when the VC is activated by perceptive stimuli which are generated by personal thought, feelings or sensory stimuli associated with the chemotherapy (Duigon, 1986). Though ANV is less frequent than post-treatment CINV, it represents a significant problem as it leads to more discomfort in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy and is usually more difficult to control than acute CINV or DNV (Grunberg, 2007). Better understanding of the mechanisms of different types of CINV may help in the development of additional effective antiemetic drugs.

2.2. Overshadowing as a model of ANV

There is a paucity of animal models for CINV, and to date, there is no completely adequate laboratory model for ANV. Some research on ANV has been conducted using models such as body rotation as a stimulus to induce nausea and related symptoms in healthy humans (Stockhorst, Steingrueber, Enck, & Klosterhalfen, 2006). Body rotation results in a number of symptoms summed as motion sickness and of these, the most significant symptoms in humans are nausea and vomiting, pallor, and cold sweating (Yates, Miller, & Lucot, 1998). In this model, the afferent signals from the vestibular system constitute the unconditioned stimulus (Stockhorst et al., 2006). Studies using body rotation model suggest that techniques such as overshadowing procedure and latent inhibition could be helpful in the prevention and reduction of ANV (Hall & Symonds, 2006; Stockhorst, Enck, & Klosterhalfen, 2007b; Symonds & Hall, 1999).

Overshadowing, as originally described by Pavlov (Pavlov, 1960), is a technique used for reducing the association between the putative CS and the US. In a usual overshadowing experiment, the subject is conditioned in an adverse experimental setting to respond to a strong stimulus, and then the stimulus is withdrawn at the next exposure to the adverse experience (Stockhorst, Enck, & Klosterhalfen, 2007c). In a small study, 16 cancer patients were assigned to either the group with overshadowing (OV+) or the group without overshadowing (OV−). At the start of all infusions of two consecutive chemotherapy cycles A and B (acquisition), the OV+ group were made to drink a distasteful saline beverage, thereby overshadowing the CS, while the OV− group were made to drink water. All patients received water in cycle C (test). In this study, no patient from the OV+ group showed ANV in cycle C (test), while two patients from OV− group developed ANV (Stockhorst et al., 1998). Overshadowing is similar to latent inhibition which consists of pre-exposing the event to be used as the CS prior to the first administration of the US, thereby reducing the amount of classical conditioning that subsequently occurs (Lubow & Moore, 1959).

Besides the body rotation model, a conditioned gaping response in rats has also been used as a model for ANV. However, these animal studies examining the gaping response in rats with respect to overshadowing (Hall & Symonds, 2006; Sansa, Artigas, & Prados, 2007; Symonds & Hall, 1999), systemic treatment with lipopolysaccharide (Chan, Cross-Mellor, Kavaliers, & Ossenkopp, 2009), tetrahydrocannabinol (Parker & Kemp, 2001), and manipulation of the endocannabinoid system (Rock, Limebeer, Mechoulam, Piomelli, & Parker, 2008) have shown inconsistent results. Another animal model for ANV has shown cannabinoids to be effective in reducing ANV (Limebeer et al., 2008; Parker & Kemp, 2001; Parker, Kwiatkowska, & Mechoulam, 2006). In addition, some conditioning procedures in other animal model systems have been used to alleviate nausea and vomiting (Davey & Biederman, 1998; Lett, 1983). However, the incidence of ANV has remained the same (Morrow et al., 1998), despite the improvements in overall CINV with the introduction of 5-HT3 receptor antagonist medications. Overall, the best method to reduce or avoid development of ANV is to avoid both vomiting and nausea from the first exposure to chemotherapy.

3. Pharmacologic Treatment of Anticipatory Nausea and Vomiting

There have been tremendous advances in the medical prophylaxis and management of acute and delayed CINV. However, many of the newly approved agents have not proven to be clinically effective in treating ANV; treating this specific type of chemotherapy-related symptom remains a challenge.

3.1. Benzodiazepines

There is some data for the use of benzodiazepines on the day of and just prior to chemotherapy administration in reducing ANV. Razavi and colleagues (Razavi 1993) performed a double-blind, placebo-controlled study assessing the addition of low-dose alprazolam (0.5-2mg per day) to a psychological support program including progressive relaxation training. Fifty-seven women undergoing adjuvant chemotherapy for early-stage breast cancer participated. Results showed a higher rate of anticipatory nausea in the placebo arm compared with alprazolam arm (18% vs. 0%, p=0.038). Significantly higher use of sleep aids (hypnotics) was also noted in the placebo arm (19% vs. 0%, p < 0.05). This small study demonstrated that adjunctive use of benzodiazepines could help reduce anticipatory symptoms among patients on chemotherapy.

Mailk and colleagues (Malik 1995) conducted a randomized trial evaluating the addition of lorazepam to a regimen of metoclopramide, dexamethasone and clemastine. A total of 180 administrations of high-dose cisplatin were included in the study. Lorazepam was found to significantly reduce the incidence of anticipatory nausea and vomiting (p < 0.05) as well as acute and delayed emesis (p=0.05 and p < 0.05 respectively). Side-effects noted in the treatment arm, as expected, included mild sedation and amnesia which can limit the use of benzodiazepines, especially in frail or elderly patients.

3.2. Other pharmacological agents

Another class of agents that is of potential interest in the treatment of ANV are cannabinoids. Two synthetic, oral formulations, dronabinol (Marinol) and nabilone (Cesamet), are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use in CINV that is refractory to conventional antiemetic therapy (Slatkin 2007). The side-effect profile of cannabinoids has limited their adoption into clinical practice especially with approval of newer effective drugs. However, there have been intriguing animal studies that suggest cannabinoids may have a role in the treatment of ANV. Parker and colleagues (Parker 2006, Parker 2011) utilized emetic reactions of the Suncus murinus (musk shrew) in their experiments. Following pairings of a distinctive contextual cue with the emetic effects of lithium chloride (toxin), the unique context acquired the potential to elicit conditioned retching (akin to ANV) in the absence of the toxin. The expression of this conditioned retching was completely suppressed by pretreatment with each of the principal cannabinoids found in marijuana. These results support the anecdotal use of cannabinoids for treatment of anticipatory symptoms although further research is needed to evaluate its potential effectiveness in the clinical setting.

The use of recommended pharmacotherapy to prevent and treat chemotherapy-induced acute and delayed emesis is critical in reducing the conditioned development of anticipatory symptoms. Advances in 5-HT3 antagonists and the development of NK-1 antagonists have dramatically improved control of acute and delayed CINV which in turn can reduce the incidence of ANV. Current guidelines (Roila 2010) recommend that for highly emetogenic chemotherapy agents, a three-drug regimen of a serotonin (5-HT3) receptor antagonist (palonosetron), dexamethasone, and NK-1 receptor antagonist (aprepitant or fosaprepitant) should be used before the beginning of chemotherapy to prevent acute CINV. Palonosetron plus dexamethasome is recommended for acute CINV from moderately emetogenic agents. For low risk chemotherapy regimens, dexamethasone or a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist or a dopamine receptor antagonist is recommended. For delayed CINV, dexamethasone and aprepitant, aprepitant alone, or dexamethasone alone can be used. To prevent ANV, the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer (MASCC) committee appropriately recommends the best possible control of acute and delayed CINV in conjunction with behavioral therapies.

4. Psychological intervention and ANV

As mentioned previously, behavioral or psychological interventions remain the best option for treating ANV. Research on behavioral treatments for cancer-related nausea began appearing in the medical literature just over three decades ago. Early studies on these behavioral treatments focused on alleviating ANV, rather than CINV, because ANV is a conditioned phenomenon treatable by means of behavioral approaches based on learning principles. Research on the behavioral treatment of conditioned adverse effects of chemotherapy has centered on two principal approaches: systematic desensitization (SD), and hypnosis (Marchioro, Azzarello, Viviani, et al., 2000). Additional behavioral techniques that have been studied have included biofeedback (Burish, Shartner & Lyles, 1981), imagery, and many variations of relaxation methods (Figueroa-Moseley, Jean-Pierre, Roscoe et al., 2007). All of these behavioral interventions have been shown to reduce ANV and to decrease levels of cancer-related anxiety and distress (Mundy, DuHamel, & Montgomery, 2003). It is interesting to note that trials testing behavioral treatment of ANV have shown that these approaches are effective even when patients’ level of anxiety is not controlled (e.g., Vasterling, Jenkins, Tope, et al., 1993), indicating that the effect of these interventions is more than purely anxiolytic. In terms of timing, interventions based on learning principles are most effective when implemented prior to the full development of the undesired conditioned response (i.e., nausea and vomiting; Figueroa-Moseley et al., 2007).

4.1. Systematic Desensitization

Systematic desensitization (SD) was originally developed to treat fears and phobias. As it is based on Pavlovian learning principles, it can be used to treat a range of learning-based difficulties, in which a particular response (e.g., anxiety, fear) has been paired with a stimulus (e.g., spiders). While research and treatment focusing on SD have declined since the 1980’s, SD remains a particularly effective intervention for the management of ANV.

ANV, and other anticipatory syndromes, display many of the same features as a phobic response. Both rely on the classical conditioning mechanism described previously. Both also involve avoidance behaviors to manage the conditioned response of anxiety or nausea. SD addresses both of these features through a three step approach: 1) construction of a hierarchy of anxiogenic stimuli, 2) learning of an incompatible response, such as relaxation, and 3) counter conditioning of the previous, maladaptive response with the incompatible response. In terms of ANV, treatment of symptoms involves identification of conditioned stimuli associated with nausea and vomiting, such as the clinic or the nurse (Morrow & Roscoe, 1997). Patients are then taught a response incompatible with feelings of nausea, such as progressive muscle relaxation (PMR). When the patient is brought into the clinic or confronted with the nurse, then, he or she practices the incompatible response, becoming relaxed and breaking the link to the conditioned response of ANV. Treatment of ANV with SD has been effective in over half the patients to whom it is administered (Morrow & Roscoe, 1997; Roscoe et al., 2011).

4.2. Hypnosis

Hypnosis was the first psychological technique used to control ANV. Hypnosis or hypnotherapy is defined as a technique where an altered state of consciousness is induced through suggestions for participants “to think, see, or experience their world in a different way” (Scott, Lagges, & LaClave, 2012). Due to its capacity for increasing suggestibility, hypnosis can used to alter levels of expectancy (Kirsch, 1999). It has also been shown to be efficacious in managing side effects in the arena of cancer treatment, such as pain (Elkins, Fisher, & Johnson, 2010; Jensen et al., 2012), and hot flashes (Elkins, Marcus, Stearns, & Hasan Rajab, 2007). In a study examining the effects of a brief presurgery hypnosis intervention in 200 patients who were scheduled to undergo excisional breast biopsy or lumpectomy, Montgomery et al. (2007) found hypnosis was superior to attention control for pain, nausea, and fatigue. A review of studies of hypnosis in CINV reported a significant effect of hypnosis compared to usual care (Richardson et al., 2007).

Hypnosis has also been used to prevent ANV related to chemotherapy (Marchioro, Azzarello, Viviani, et al., 2000). Although hypnosis was the first psychological technique used to control ANV, few controlled, randomized clinical trials of hypnosis have been conducted. In one of these few trials, Zeltzer et al. reported that a combined intervention of hypnosis and counseling in a sample of 19 children and adolescents undergoing chemotherapy resulted in significant reduction of nausea and vomiting symptoms after the completion of intervention (Zeltzer, LeBaron, & Zeltzer, 1984). In a study of 16 adult patients with cancer who had undergone four chemotherapy sessions and reported anticipatory nausea and vomiting, relaxation and hypnosis was followed by complete relief from ANV (Marchioro et al., 2000). Overall, hypnosis has most often been used with pediatric and adolescent cancer patients, which may be due to the fact that children are more readily hypnotized than adults (Mackenzie & Frawley, 2007).

For the practicing oncologist, hypnosis is a potentially useful intervention for the control of treatment side effects (Thomson, 2003). There are no undesirable side effects, no special equipment is needed, and it requires little physical effort on the patient’s part. Research shows that the techniques used to induce a hypnotic state in a patient are not difficult to learn and apply (Martinez-Tendero, Capafons, Weber, et al. 2001). In addition, patients can be taught self-hypnosis techniques, thereby empowering them by giving them an important tool for managing their own health (Deng & Cassileth, 2005; Martinez-Tendero et al., 2001).

4.3. Biofeedback, Imagery, and Relaxation

Other behavioral treatments for ANV center on relaxation and management of expectancies, the two principles targeted by SD and hypnosis. An early trial showed the efficacy of biofeedback in reducing severity of ANV through producing a relaxation response in patients (Burish, Shartner, & Lyles, 1981). Guided imagery, similarly, has been used to produce a relaxation response or to manage negative expectancies about treatment (Lyles, Burisch, Krozely, 1982). Guided imagery involves descriptive statements by a therapist or other provider to assist a patient in constructing a mental picture that would promote relaxation or a reduction in anxiety, such as a beach scene or an image of cancer cells shrinking. Progressive muscle relaxation (PMR) is often used as an incompatible response in SD interventions. PMR involves systematically tensing and relaxing muscle groups throughout the body until a full-body relaxation response is achieved (Arakawa, 1997; Yoo, Ahn, Kim, Kim, & Han, 2005). Used alone, PMR appears most effective in reducing severity of nausea, vomiting, and other side effects that develop after administration of chemotherapy (Molassiotis, Yung, & Yam, 2002). When combined with systematic desensitization or guided imagery, it has proven to be efficacious in reducing ANV (Yoo, Ahn, Kim, et al., 2005). Other forms of learned relaxation (Morrow & Morrell, 1982; Redd, Montgomery, & DuHamel, 2001) have been shown to be effective; a randomized controlled study of 48 patients undergoing chemotherapy found a relaxation intervention to be beneficial in controlling ANV in those patients who did not have an “information-gathering coping style”. (Lerman et al., 1990) Finally, shading into the realm of complementary treatment approaches, a study of a yoga intervention for CINV reported a significantly reduction in anticipatory nausea and vomiting in a sample of 62 early breast cancer patients (Raghavendra et al., 2007).

5. Complementary and Alternative Treatment of ANV

Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) has been increasingly used by cancer patients experiencing ANV; the reasons for such use include the inadequate response of current medications to this side effect and the refractory nature of ANV (Jindal, Ge, & Mansky, 2008; R. J. Morrow GR, Kirshner JJ, Hynes HE, Rosenbluth RJ, 1998).

5.1. Acupuncture/Acupressure

Practiced as a part of traditional Chinese medicine, acupuncture has shown promise in relieving various symptoms associated with cancer and its treatment (O’Regan & Filshie, 2010). This includes CINV, where acupuncture points P6 and ST36 (Ma & Li, 2001) have been used to apply stimulation by means of needles, heat, acupressure using bands, pressure with fingers, or electro-acupuncture. Such stimulation is believed to bring about a balanced state of energy in the body (Kang, Jeong, Kim, & Lee, 2011; NCI, 2012). Some randomized control trials of acupuncture have yielded evidence of control of ANV when acupuncture is used alone (Chao, 2009; Ezzo, 2006; R. Konno, 2010), and when it is used in combination with an antiemetic (Shin, Kim, Shin, & Juon, 2004; Yang et al., 2009) or counseling (Suh, 2012).

A randomized four-arm clinical trial using acupressure wristbands has shown beneficial effects on ANV; however, this effect was primarily seen in those who had high expectancy of nausea and vomiting and not in those who reported low expectancy of nausea and vomiting (Roscoe et al., 2010). This research provides direct evidence of the intersection between psychological factors, anticipatory nausea, and treatment modalities. Given that pressure bands are effective primarily for those with an expectancy of nausea, the bands’ ability to control nausea can largely be accounted for by patients’ expectations of efficacy, i.e., a placebo effect (Roscoe, Morrow, Hickok, et al., 2003). Empirical evidence the role of expectancy in the bands’ effectiveness comes from a multicenter study examining the efficacy of acupressure wrist bands in reducing chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Patients who received the acupressure bands and expected them to be effective (N = 112) experienced significantly less nausea on the day of treatment, as well as less overall nausea, than those who did not expect them to be effective (N = 121), and less than those in the no-band control group (N = 232). They also used less antiemetic medication and reported a higher quality of life (QOL), both Ps < 0.05. There were no significant differences in any outcome measures between patients who received the acupressure bands and did not expect them to be effective and the no-band control group. Results from two other research groups showing that sham acupressure bands were effective in reducing nausea suggest that an expectancy/placebo effect was present in these studies as well (Ferrara-Love, Sekeres, & Bircher, 1996; Alkaissi, Stalnert, Kalman, 1999).

In spite of the evidence of beneficial effects of acupuncture and acupressure in CINV, confirmatory evidence regarding ANV is still lacking. In pediatric populations acupuncture has been shown to be effective in controlling nausea occurring during the postoperative period; however, there is no definitive evidence of similar effects in chemotherapy-related ANV (Jindal et al., 2008).

5.2. Herbal Supplements

Among the herbal supplements ginger is the most studied for the relief of ANV. A study of ginger in 576 patients with chemotherapy-related nausea and vomiting revealed significant beneficial effects of 0.5g and 1.0g ginger in acute CINV. This is an encouraging finding because the patients in this study took ginger capsules three days prior to starting their chemotherapy and the study also showed that ANV was significantly contributing to acute nausea (Ryan et al., 2012). Perhaps a longer pre-chemotherapy regimen of ginger could be useful in reducing ANV leading to a better control of acute nausea after the chemotherapy is started.

5.3. The Effect of Optimism on ANV

A positive attitude is often considered to be a beneficial attribute for patients who are confronted with a serious health concern. Popular authors, such as Bernie Siegel and the late Norman Cousins, have expounded on the virtues of positive thinking and suggest that it is related to better health outcomes. Scheier & Carver (1987) theorize that patient optimism has a significant positive effect both directly and indirectly on health and well-being. These researchers conceptualize optimism as a stable personality trait and use the term dispositional optimism to describe individuals with more global positive expectations. Optimism has been associated with increased motivation and persistence at tasks as well as an array of positive health-related outcomes, including lower postpartum depression, higher QOL 8 months after coronary artery bypass surgery, fewer physical symptoms of poor health and less emotional distress during and after radiation therapy. Pessimism, by contrast, is associated with depression and lowered disease resistance in breast cancer patients, poor health in middle and late adulthood, and more rapidly deteriorating health and increased morbidity in AIDS patients. Interestingly, a general tendency to be optimistic does not appear to predict degree of nausea from chemotherapy, even though specific nausea expectancies are strong predictors of this side effect (Roscoe et al., 2006). Treatment approaches that could tap into the construct of optimism to address negative expectancies, however, could prove efficacious in controlling ANV by enabling patients to view their chemotherapy side effects with optimism.

In conclusion, current anti-emetics are associated with bothersome side-effects in patients with cancer (Bergkvist & Wengstrom, 2006) and may not address the underlying mechanisms of ANV. ANV appears to be related to psychological, learning-related processes, and so may best be addressed by behavioral or psychological treatments. However, the factors of greater tolerability and fewer side effects of CAM techniques make them attractive alternatives to the less effective pharmacologic options available for the treatment of ANV. Behavioral and CAM techniques could also allow the patients to apply interventions to themselves (Rie Konno, 2010), allowing for greater patient self-efficacy and treatment control. Additional research is needed to confirm initial indication of the beneficial effects of some of these CAM treatments and to identify new, palatable approaches for the management of ANV.

References

- Alkaissi A, Stalnert M, Kalman S. Effect and placebo effect of acupressure (P6) on nausea and vomiting after outpatient gynaecological surgery. Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica. 1999;43(3):270–4. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-6576.1999.430306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrykowski MA. The role of anxiety in the development of anticipatory nausea in cancer chemotherapy: A review and synthesis. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1990;52:458–475. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199007000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arakawa S. Relaxation to reduce nausea, vomiting, and anxiety induced by chemotherapy in Japanese patients. Cancer Nursing. 1997;20(5):342–349. doi: 10.1097/00002820-199710000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barsky AJ, Saintfort R, Rogers MP, Borus JF. Nonspecific medication side effects and the nocebo phenomenon. JAMA. 2002;287:622–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.5.622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergkvist Karin, Wengstrom Yvonne. Symptom experiences during chemotherapy treatment--with focus on nausea and vomiting. European Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2006;10(1):21–29. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2005.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackshaw LA, Brookes SJ, Grundy D, Schemann M. Sensory transmission in the gastrointestinal tract. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2007;19(Suppl1):1–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2006.00871.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borison HL. Area postrema: chemoreceptor circumventricular organ of the medulla oblongata. Prog Neurobiol. 1989;32:351–390. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(89)90028-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burish TG, Shartner CD, Lyles JN. Effectiveness of multiple muscle-site EMG biofeedback and relaxation training in reducing the aversiveness of cancer chemotherapy. Biofeedback Self Regul. 1981;6:523–535. doi: 10.1007/BF00998737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke CW, Mason JN, Surman SL, et al. Illumination of parainfluenza virus infection and transmission in living animals reveals a tissue-specific dichotomy. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan MY, Cross-Mellor SK, Kavaliers M, Ossenkopp KP. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) blocks the acquisition of LiCl-induced gaping in a rodent model of anticipatory nausea. Neurosci. Lett. 2009;450:301–305. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.11.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao L-F, Zhang AL, Liu H-E, Cheng M-H, Lam H-B, Lo SK. The efficacy of acupoint stimulation for the management of therapy-related adverse events in patients with breast cancer: a systematic review. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;118(255-267) doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0533-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colagiuri B, Roscoe JA, Morrow GR, Atkins JN, Giguere JK, Colman LK. How do patient expectancies, quality of life, and postchemotherapy nausea interrelate? Cancer. 2008;113:654–61. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crow R, Gage H, Hampson S, Hart J, Kimber A, Thomas H. The role of expectancies in the placebo effect and their use in the delivery of health care: A systematic review. Health Technology Assessment (Rockville, Md) 1999;3(3):1–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darmani NA, Ray AP. Evidence for a re-evaluation of the neurochemical and anatomical bases of chemotherapy-induced vomiting. Chem. Rev. 2009;109:3158–3199. doi: 10.1021/cr900117p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davey VA, Biederman GB. Conditioned antisickness: indirect evidence from rats and direct evidence from ferrets that conditioning alleviates drug-induced nausea and emesis. J Exp Psychol Anim Behav Process. 1998;24:483–491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng G, Cassileth BR. Integrative oncology: complementary therapies for pain, anxiety, and mood disturbance. Ca: a Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2005;55(2):109–16. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.2.109. [Review] [64 refs] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duigon A. Anticipatory Nausea and Vomiting Associated with Cancer Chemotherapy. ONF. 1986;13:35–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elkins Gary, Fisher William, Johnson Aimee. Mind-body therapies in integrative oncology. Current Treatment Options in Oncology. 2010;11(3-4):128–140. doi: 10.1007/s11864-010-0129-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elkins Gary, Marcus Joel, Stearns Vered, Hasan Rajab M. Pilot evaluation of hypnosis for the treatment of hot flashes in breast cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncology. 2007;16(5):487–492. doi: 10.1002/pon.1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezzo JM, Richardson MA, Vickers A, Allen C, Dibble SL, Issell BF, Lao L, Pearl M, Ramirez G, Roscoe J, Shen J, Shivnan JC, Streitberger K, Treish I, Zhang G. Acupuncture-point stimulation for chemotherapy-induced nausea or vomiting. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006:CD002285. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002285.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrara-Love R, Sekeres L, Bircher NG. Nonpharmacologic treatment of postoperative nausea. J Perianesth Nurs. 1996;11:378–83. doi: 10.1016/s1089-9472(96)90048-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feyer P, Jordan K. Update and new trends in antiemetic therapy: the continuing need for novel therapies. Ann. Oncol. 2011;22:30–38. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueroa-Moseley C, Jean-Pierre P, Roscoe JA, Ryan JL, Kohli S, Palesh OG, Ryan EP, Carroll J, Morrow GR. Behavioral interventions in treating anticipatory nausea and vomiting. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 2007;5:44–50. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2007.0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunberg SM. Antiemetic activity of corticosteroids in patients receiving cancer chemotherapy: dosing, efficacy, and tolerability analysis. Annals of Oncology. 2007;18(2):233–240. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunberg SM, Ireland A. Epidemilogy of Chemotherapy-induced Nausea and Vomiting. Adv. Stud. Nurs. 2005;3:9–15. [Google Scholar]

- Hahn RA. The nocebo phenomenon: Concept, evidence, and implications for public health. Prev Med. 1997;26:607–11. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1996.0124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall G, Symonds M. Overshadowing and latent inhibition of context aversion conditioning in the rat. Auton Neurosci. 2006;129:42–49. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2006.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesketh PJ. Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2482–2494. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0706547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornby PJ. Central neurocircuitry associated with emesis. Am J Med. 2001;111(Suppl 8A):106S–112S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(01)00849-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute, National Cancer . Nausea and Vomiting (PDQ) 2012. from http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/supportivecare/nausea/Patient/page1/AllPages/Print. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen Mark P., Gralow Julie R., Braden Alan, Gertz Kevin J., Fann Jesse R., Syrjala Karen L. Hypnosis for symptom management in women with breast cancer: a pilot study. International Journal of Clinical & Experimental Hypnosis. 2012;60(2):135–159. doi: 10.1080/00207144.2012.648057. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00207144.2012.648057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jindal Vanita, Ge Adeline, Mansky Patrick J. Safety and efficacy of acupuncture in children: a review of the evidence. Journal of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology. 2008;30(6):431–442. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e318165b2cc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang Hyun-Sun, Jeong Daun, Kim Dong-Il, Lee Myeong Soo. The use of acupuncture for managing gynaecologic conditions: An overview of systematic reviews. Maturitas. 2011;68(4):346–354. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2011.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirsch I. Response expectancy as a determinant of experience and behavior. Am Psychol. 1985;40:1189–202. [Google Scholar]

- Kirsch I. Specifying nonspecifics: Psychological mechanisms of placebo effects. In: Harrington A, editor. The placebo effect: An interdisciplinary exploration. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 1997. pp. 166–186. [Google Scholar]

- Kirsch I. Clinical hypnosis as a nondeceptive placebo. In: Kirsch I, Capafons A, et al., editors. Clinical hypnosis and self-regulation: Cognitive-behavioral perspectives. Dissociation, trauma, memory, and hypnosis book series. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 1999. pp. 211–25. [Google Scholar]

- Konno R. Cochrane review summary for cancer nursing: acupuncture-point stimulation for chemotherapy-induced nausea or vomiting. Cancer Nurs. 2010;33:479–480. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3181f104bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konno Rie. Cochrane review summary for cancer nursing: acupuncture-point stimulation for chemotherapy-induced nausea or vomiting. Cancer Nursing. 2010;33(6):479–480. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3181f104bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerman C, Rimer B, Blumerberg B, Christinizio S, Engstrom P, MacElwee N, Seay J. Effects of coping style and relaxation on cancer chemotherapy side-effects and emotional responses. Cancer Nursing. 1990;13(5):308–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leslie RA, Reynolds DJM. Chapter 6: Neurotransmitters and receptors in the emetic pathway. Chapman & Hall Medical; London: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Lesurtel M, Soll C, Graf R, Clavien PA. Role of serotonin in the hepatogastrointestinal tract: an old molecule for new perspectives. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65(6):940–952. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-7377-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lett BT. Pavlovian drug-sickness pairings result in the conditioning of an antisickness response. Behav Neurosci. 1983;97:779–784. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.97.5.779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limebeer CL, Krohn JP, Cross-Mellor S, Litt DE, Ossenkopp KP, Parker LA. Exposure to a context previously associated with nausea elicits conditioned gaping in rats: a model of anticipatory nausea. Behav Brain Res. 2008;187:33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2007.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubow RE, Moore AU. Latent inhibition: the effect of non reinforced pre-exposure to the conditional stimulus. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1959;52:415–419. doi: 10.1037/h0046700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyles JN, Burish TG, Krozely MG, Oldham RK. Efficacy of relaxation training and guided imagery in reducing the aversiveness of cancer chemotherapy. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 1982;50(4):509–524. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.50.4.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J, Li YJ. Meta-analysis of TCM pattern diagnosis in 2492 primary HCC Patients TCM Res. TCM Research. 2001;14(3):15–16. [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie A, Frawley GP. Preoperative hypnotherapy in the management of a child with anticipatory nausea and vomiting. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2007;35:784–787. doi: 10.1177/0310057X0703500522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malik IA, Khan WA, Qazilbash M, et al. Clinical efficacy of lorazepam in prophylaxis of anticipatory, acute and delayed nausea and vomiting induced by high doses of cisplatin: A prospective randomized trial. Am J Clin Oncol. 1995;18:170–175. doi: 10.1097/00000421-199504000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchioro G, Azzarello G, Viviani F, Barbato F, Pavanetto M, Rosetti F, Vinante O. Hypnosis in the treatment of anticipatory nausea and vomiting in patients receiving cancer chemotherapy. Oncology. 2000;59(2):100–104. doi: 10.1159/000012144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Tendero J, Capafons A, Weber V, Cardena E. Rapid self-hypnosis: a new self-hypnosis method and its comparison with the Hypnotic Induction Profile (HIP) American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis. 2001;44(1):3–11. doi: 10.1080/00029157.2001.10403451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matteson S, Roscoe J, Hickok J, Morrow GR. The role of behavioral conditioning in the development of nausea. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186(5 Suppl Understanding):S239–243. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.122597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchioro G, Azzarello G, Viviani F, Barbato F, Pavanetto M, Rosetti F, Pappagallo GL, Vinante O. Hypnosis in the treatment of anticipatory nausea and vomiting in patients receiving cancer chemotherapy. Oncology (Huntingt) 2000;59:100–104. doi: 10.1159/000012144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller AD, Leslie RA. The area postrema and vomiting. Front Neuroendocrinol. 1994;15:301–320. doi: 10.1006/frne.1994.1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molassiotis A, Yung HP, Yam BMC, Chan FYS, Mok TS. The effectiveness of progressive muscle relaxation training in managing chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in Chinese breast cancer patients: A randomized controlled trial. Support Care Cancer. 2002;10:237–246. doi: 10.1007/s00520-001-0329-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery GH, Bovbjerg DH, Schnur JB, David D, Goldfarb A, Weltz CR, et al. A randomized clinical trial of a brief hypnosis intervention to control side effects in breast surgery patients. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99(17):1304–12. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery GH, Tomoyasu N, Bovbjerg DH, Andrykowski MA, Currie VE, Jacobsen PB, Redd WH. Patients’ pretreatment expectations of chemotherapy-related nausea are an independent predictor of anticipatory nausea. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 1998;20:104–109. doi: 10.1007/BF02884456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrow GR, Morrell C. Behavioral treatment for the anticipatory nausea and vomiting induced by cancer chemotherapy. New England Journal of Medicine. 1982;307(24):1476–1480. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198212093072402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrow GR, Roscoe JA. Anticipatory nausea and vomiting: Models, mechanisms and management. In: Dicato M, editor. Medical management of cancer treatment induced emesis. Martin Dunitz; London: 1997. pp. 149–66. [Google Scholar]

- Morrow GR, Roscoe JA, Kirshner JJ, Hynes HE, Rosenbluth RJ. Anticipatory nausea and vomiting in the era of 5-HT3 antiemetics. Support Care Cancer. 1998;6:244–247. doi: 10.1007/s005200050161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrow GR, Roscoe JA, Hickok JT. Nausea and Vomiting. Oxford University Press; New York, NY: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Morrow GR, Roscoe JA, Kirshner JJ, Hynes HE, Rosenbluth RJ. Anticipatory nausea and vomiting in the era of 5-HT3 antiemetics. Support Care Cancer. 1998;6:244–247. doi: 10.1007/s005200050161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mundy EA, DuHamel KN, Montgomery GH. The efficacy of behavioral interventions for cancer treatment-related side effects. Semin Clin Neuropsychiatry. 2003;8:253–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navari RM. Pharmacological management of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: focus on recent developments. Drugs. 2009;69(5):515–533. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200969050-00002. doi: 2 [pii] 10.2165/00003495-200969050-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NCI Acupuncture. 2012 http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/cam/acupuncture/healthprofessional. Retrieved November, 2012, from http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/cam/acupuncture/healthprofessional.

- Neese RM, Carli T, Curtin G, Kleinman PD. Pretreatment nausea in cancer chemotherapy: A conditioned response? Psychosom Med. 1980;42:33–36. doi: 10.1097/00006842-198001000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Regan David, Filshie Jacqueine. Acupuncture and cancer. Autonomic Neuroscience-Basic & Clinical. 2010;157(1-2):96–100. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker LA, Kemp SW. Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) interferes with conditioned retching in Suncus murinus: an animal model of anticipatory nausea and vomiting (ANV) Neuro Report. 2001;12:749–751. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200103260-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker LA, Kwiatkowska M, Mechoulam R. Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol and cannabidiol, but not ondansetron, interfere with conditioned retching reactions elicited by a lithium-paired context in Suncus murinus: An animal model of anticipatory nausea and vomiting. Physiol Behav. 2006;87:66–71. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2005.08.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker LA, Rock EM, Limebeer CL. Regulation of nausea and vomiting by cannabinoids. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;163:1411–1422. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.01176.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlov IP. Conditioned reflexes. Dover; New York: 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Raghavendra RM, Nagarathna R, Nagendra HR, Gopinath KS, Srinath BS, Ravi BD, Nalini R. Effects of an integrated yoga programme on chemotherapy-induced nausea and emesis in breast cancer patients. European Journal of Cancer Care. 2007;16(6):462–474. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2006.00739.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsay DS, Woods SC. Biological consequences of drug administration: implications for acute and chronic tolerance. Psychol. Rev. 1997;104:170–193. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.104.1.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rang H, Dale M, Ritter J, Flower R. Pharmacology. 6 th ed. Vol. 391. Elsevier; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Razavi D, Delvaux N, Farvacques C, et al. Prevention of adjustment disorders and anticipatory nausea secondary to adjuvant chemotherapy: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study assessing the usefulness of alprazolam. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:1384–1390. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.7.1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redd WH, Montgomery GH, DuHamel KN. Behavioral intervention for cancer treatment side effects. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2001;93(11):810–823. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.11.810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson J, Smith JE, McCall G, Richardson A, Pilkington K, Kirsch I. Hypnosis for nausea and vomiting in cancer chemotherapy: a systematic review of the research evidence. European Journal of Cancer Care. 2007;16(5):402–412. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2006.00736.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rock EM, Limebeer CL, Mechoulam R, Piomelli D, Parker LA. The effect of cannabidiol and URB597 on conditioned gaping (a model of nausea) elicited by a lithium-paired context in the rat. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2008;196:389–395. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0970-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roila F, Herrstedt J, Aapro M, et al. Group, E.M.G.W. Guideline update for MASCC and ESMO in the prevention of chemotherapy- and radiotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: results of the Perugia consensus conference. Annals of Oncology: official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology/ESMO. 2010;21(Suppl 5):232–243. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roscoe JA, Bushunow P, Morrow GR, Hickok JT, Kuebler PJ, Jacobs A, et al. Patient expectation is a strong predictor of severe nausea after chemotherapy: A University of Rochester Community Clinical Oncology Program study of patients with breast carcinoma. Cancer. 2004;101(11):2701–8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roscoe JA, Jean-Pierre P, Shelke AR, Kaufman ME, Bole C, Morrow GR. The role of patients’ response expectancies in side effect development and control. Current Problems in Cancer. 2006;30(2):40–98. doi: 10.1016/j.currproblcancer.2005.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roscoe JA, Morrow GR, Aapro MS, Molassiotis A, Olver I. Anticipatory nausea and vomiting. Supportive care in cancer: official journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer. 2011;19(10):1533–1538. doi: 10.1007/s00520-010-0980-0. doi: 10.1007/s00520-010-0980-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roscoe JA, Morrow GR, Colagiuri B, Heckler CE, Pudlo BD, Colman L, et al. Insight in the prediction of chemotherapy-induced nausea. Support Care Cancer. 2010;18(7):869–76. doi: 10.1007/s00520-009-0723-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roscoe JA, Morrow GR, Hickok JT, Bushunow PW, Pierce HI, Flynn PJ, et al. The efficacy of acupressure and acustimulation wrist bands for the relief of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: A URCC CCOP multicenter study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2003;26(2):731–42. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(03)00254-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roscoe JA, O’Neill M, Jean-Pierre P, Heckler CE, Kaptchuk TJ, Bushunow P, Smith B. An Exploratory Study on the Effects of an Expectancy Manipulation on Chemotherapy-Related Nausea. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2010;40(3):379–390. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.12.024. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.12.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubenstein EB, Slusher BS, Rojas C, Navari RM. New approaches to chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: from neuropharmacology to clinical investigations. Cancer J. 2006;12:341–347. doi: 10.1097/00130404-200609000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudd JA, Andrews PL. Mechanisms of acute, delayed, and anticipatory emesis induced by anticancer therapies. Jones & Bartlett; Sudbury, MA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan Julie L., Heckler Charles E., Roscoe Joseph A., Dakhil Shaker R., Kirshner Jeffrey, Flynn Patrick J., Morrow Gary R. Ginger (Zingiber officinale) reduces acute chemotherapy-induced nausea: a URCC CCOP study of 576 patients. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2012;20(7):1479–1489. doi: 10.1007/s00520-011-1236-3. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00520-011-1236-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sansa J, Artigas AA, Prados J. Overshadowing and potentiation of illness-based context conditioning. Psicológica. 2007;28:193–214. [Google Scholar]

- Scheier MF, Carver CS. Dispositional optimism and physical well-being: The influence of generalized outcome expectancies on health. J Pers. 1987;55:169–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1987.tb00434.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott Eric L., Lagges Ann, LaClave Linn. The Oxford handbook of hypnosis: theory, research, and practice: Treating children using hyonosis. Oxford University Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Shin Yeong Hee, Kim Tae Im, Shin Mi Sook, Juon Hee-Soon. Effect of acupressure on nausea and vomiting during chemotherapy cycle for Korean postoperative stomach cancer patients. Cancer Nursing. 2004;27(4):267–274. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200407000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slatkin NE. Cannabinoids in the treatment of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: beyond prevention of acute emesis. J Support Oncol. 2007;5:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockhorst U, Enck P, Klosterhalfen S. Role of classical conditioning in learning gastrointestinal symptoms. World journal of gastroenterology: WJG. 2007a;13(25):3430–3437. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i25.3430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockhorst U, Enck P, Klosterhalfen S. Role of classical conditioning in learning gastrointestinal symptoms. World J. Gastroenterol. 2007b;13:3430–3437. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i25.3430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockhorst U, Enck P, Klosterhalfen S. Role of classical conditioning in learning gastrointestinal symptoms. World J. Gastroenterol. 2007c;13:3430–3437. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i25.3430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockhorst U, Klosterhalfen S, Klosterhalfen W, et al. Anticipatory nausea in cancer patients receiving chemotherapy: classical conditioning etiology and therapeutical implications. Integr Physiol Behav Sci. 1993;28:177–181. doi: 10.1007/BF02691224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockhorst U, Steingrueber H-J, Enck P, Klosterhalfen S. Pavlovian conditioning of nausea and vomiting. Autonomic Neuroscience: Basic and Clinical. 2006;129:50–57. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2006.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockhorst U, Wiener JA, Klosterhalfen S, Klosterhalfen W, Aul C, Steingruber HJ. Effects of overshadowing on conditioned nausea in cancer patients: an experimental study. Physiol Behav. 1998;64:743–753. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(98)00135-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suh Eunyoung Eunice. The effects of P6 acupressure and nurse-provided counseling on chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in patients with breast cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2012;39(1):E1–9. doi: 10.1188/12.ONF.E1-E9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Symonds M, Hall G. Overshadowing not potentiation of illness-based contextual conditioning by a novel taste. Anim Learn Behav. 1999;27:379–390. [Google Scholar]

- Thomson L. A project to change the attitudes, beliefs and practices of health professionals concerning hypnosis. American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis. 2003 Jul.46(1):31–44. doi: 10.1080/00029157.2003.10403563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasterling J, Jenkins RA, Tope DM, Burish TG. Cognitive distraction and relaxation training for the control of side effects due to cancer chemotherapy. J Behav Med. 1993;16:65–80. doi: 10.1007/BF00844755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson M. Anticipatory nausea and vomiting: broadening the scope of psychological treatments. Support Care Cancer. 1993;1:171–177. doi: 10.1007/BF00366442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson M, McCarron J, Law M. Anticipatory nausea and emesis, and psychological morbidity: Assessment of prevalence among out-patients on mild to moderate chemotherapy regimens. Br J Cancer. 1992;66:862–866. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1992.374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Yan, Zhang Yue, Jing Nian-cai, Lu Yi, Xiao Hong-yu, Xu Guang-li, Duan Qi-liang. Electroacupuncture at Zusanli (ST 36) for treatment of nausea and vomiting caused by the chemotherapy of the malignant tumor: a multicentral randomized controlled trial. Zhongguo Zhenjiu. 2009;29(12):955–958. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yates BJ, Miller AD, Lucot JB. Physiological basis and pharmacology of motion sickness: an update. Brain Res. Bull. 1998;47:395–406. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(98)00092-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo Hee J., Ahn Se H., Kim Sung B., Kim Woo K., Han Oh S. Efficacy of progressive muscle relaxation training and guided imagery in reducing chemotherapy side effects in patients with breast cancer and in improving their quality of life. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2005;13(10):826–833. doi: 10.1007/s00520-005-0806-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeltzer L, LeBaron S, Zeltzer PM. The effectiveness of behavioral intervention for reduction of nausea and vomiting in children and adolescents receiving chemotherapy. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 1984;2(6):683–690. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1984.2.6.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]