Abstract

Infectious disease prevention and control has been among the top public health objectives during the last century. However, controlling disease due to pathogens that move between animals and humans has been challenging. Such zoonotic pathogens have been responsible for the majority of new human disease threats and a number of recent international epidemics. Currently, our surveillance systems often lack the ability to monitor the human–animal interface for emergent pathogens. Identifying and ultimately addressing emergent cross-species infections will require a “One Health” approach in which resources from public veterinary, environmental, and human health function as part of an integrative system. Here we review the epidemiology of bovine zoonoses from a public health perspective.

Key Words: : Cattle zoonoses, Emerging pathogens, Occupational exposure, Epidemiology, Public health

Introduction

Over the past three decades, emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases have been recognized as one of the most significant public health problems. Infectious diseases are the leading cause of death worldwide and, despite modern healthcare, infectious diseases remain a leading cause of death in the United States (Board on International Health 1997, Armstrong et al. 1999). Emerging infectious diseases (EIDs) have been described as outbreaks of previously unknown diseases or previously recognized diseases whose incidence has expanded significantly in the past two decades (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases 2010). Diseases that have resurfaced after a decline in incidence are classified as re-emerging. As diagnostic and research capabilities have advanced, pathogens able to infect both humans and animals have increasingly been recognized as a major source of emergent human diseases (Jones et al. 2008).

The incidence of EID events has grown since the 1940s, despite controlling for increased reporting effort, thus providing the first analytical support that the threat of EIDs to global health is increasing (Jones et al. 2008). Further analysis revealed these EID events are dominated by zoonotic pathogens (60.3%). Similar findings have been published elsewhere (Taylor et al. 2001;Woolhouse et al. 2005a) and have been used in a 2006 World Health Organization (WHO) report highlighting the need for increased research and control efforts for neglected zoonotic diseases in poverty alleviation efforts (World Health Organization 2006). Zoonotic pathogens can substantially impact public health both in terms of disease morbidity as well as in socioeconomic factors such as livestock productivity. The consequences of subsequent disease in humans and animals are particularly profound among people living in developing nations.

With the emerging nature of zoonotic pathogens, it seems prudent that we consider the current and future role domestic animals may play as potential sources of novel diseases. An analysis by Woolhouse et al. found ungulates to be the most important nonhuman host, both in terms of the number of zoonotic pathogen species supported as well as among emerging and re-emerging zoonotic species (Woolhouse 2005a). In this review, we discuss emerging zoonotic pathogens of cattle, because they are one of the most important domestic livestock animals to human society (United States Department of Agriculture: Interagency Agricultural Projections Committee 2011). Unlike previous zoonotic reports involving cattle zoonoses (Hoar et al. 2001, McQuiston and Childs 2002, Abalos and Retamal 2004, Bradley and Liberski 2004, Arricau-Bouvery and Rodolakis 2005, Collins 2006, Davies 2006, O'Handley and Olson 2006, O'Handley 2007, Mattison et al. 2007, Cavirani 2008, Indra et al. 2009, Rodolakis 2009, Ingram et al. 2010, Seleem et al. 2010, Torgerson and Togerson 2010), this review will not focus on one or a select group of pathogens, but rather on the epidemiology of cattle zoonotic diseases due to their potentially substantial role in global public health. Previous reports have documented the characteristics of zoonotic pathogens, such as life cycle, geographic location, method of infection, and symptoms. However, other epidemiologic data, such as transmission, risk factors, prevalence, incidence rates, genetic evolution, and environmental risk factors, are often not available. Furthermore, few case reports are available documenting or discussing zoonotic transmission events of bovine pathogens. It is our belief that transmission events between cattle and humans occur predominantly through the bridging population of agricultural workers. Studying and educating these workers presents a unique opportunity to intervene in a number of disease transmission cycles. The recognition of the need for a comprehensive public health system has given rise to “One Health,” an integrative effort of multiple disciplines at the local, national, and global health levels to attain optimal health for people, animals, and the environment (American Veterinary Medical Association 2008). Hence, in this report we sought to not only summarize cattle zoonotic disease data to assist public health, veterinary health, and research professionals to identify areas that merit further study, but also to elucidate how such diseases may occur in a practical setting.

The Human–Cattle Nexus

Domestic cattle have played a central role in human society for centuries. They provide essential sources of meat, milk, other dairy products, fertilizer for crops, clothing, and animal traction. This role continues to be vital in the lives of the most economically challenged people as cattle are often an important source of food security and revenue. For many in the developing world, cattle represent the most valuable property they own—often being reserved only for the wealthiest in a society (Coleman 2002). In many developing countries, recent urbanization, population growth, and rising incomes have resulted in rapid growth and transformation of livestock production in the absence of a public health framework, thus creating an increased opportunity for zoonotic diseases to threaten human health.

Groups with greater exposure to cattle and cattle products have increased risk of contracting bovine zoonotic infections. These groups include livestock handlers, veterinarians, abattoir workers, meat inspectors, laboratory staff handling biological samples from infected cattle, and persons consuming unpasteurized milk or other diary products and improperly prepared meats. As with many other infectious diseases, infants, the elderly, the immunocompromised, and those with other underlying health conditions are at increased risk of contracting bovine zoonotic infections (McMichael et al. 2002).

The role of cattle in modern societies is equally significant. For example, in 2010 almost half (935,000) of the 2.2 million farms in the United States used cattle for beef and dairy production, an estimated $68.5 billion industry (United States Department of Agriculture: Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service 2011). The US Department of Agriculture has projected an increase in the cattle industry over the next decade, largely as a result of increased demand in meat exports (United States Department of Agriculture: Interagency Agricultural Projections Committee 2011). Cattle are not equally distributed among the nations of the world, with the top five countries in terms of numbers of cattle, as well as dairy and meat production, comprising more than half of the world's cattle commodity (Table 1). Enhanced public health awareness and surveillance in these locations will be particularly important in decreasing morbidity and mortality associated with bovine zoonotic diseases. With 1.4 billion cattle globally (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations 2010), the interface between humans and cattle continues to be a vital component to our public health system.

Table 1.

Global Cattle Statistics for the Year 2009–2010: Statistics from Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations 2010a

| Country | Total | Percentage | Global total | Percentage of global total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

2009 |

Cattle population (head) |

India |

206,400,000 |

14.54% |

1,419,528,556 |

50.34% |

| |

|

Brazil |

205,260,000 |

14.46% |

|

|

| |

|

Europe (total) |

125,797,753 |

8.86% |

|

|

| |

|

United States |

94,521,000 |

6.66% |

|

|

| |

|

China |

82,624,751 |

5.82% |

|

|

| |

Cattle meat (tons) |

United States |

11,891,100 |

19.26% |

61,730,630 |

63.02% |

| |

|

Europe (total) |

10,907,885 |

17.67% |

|

|

| |

|

Brazil |

6,661,630 |

10.79% |

|

|

| |

|

China |

6,060,569 |

9.82% |

|

|

| |

|

Argentina |

3,378,460 |

5.47% |

|

|

| |

Cattle milk (tons) |

Europe (total) |

207,114,043 |

35.33% |

586,239,893 |

69.71% |

| |

|

United States |

85,880,500 |

14.65% |

|

|

| |

|

India |

47,825,000 |

8.16% |

|

|

| |

|

China |

35,509,831 |

6.06% |

|

|

| |

|

Russia |

32,325,800 |

5.51% |

|

|

|

2010 |

Cattle population (head) |

India |

210,200,000 |

14.71% |

1,428,701,438 |

50.51% |

| |

|

Brazil |

209,541,000 |

14.67% |

|

|

| |

|

Europe (total) |

124,248,533 |

8.70% |

|

|

| |

|

United States |

93,881,200 |

6.57% |

|

|

| |

|

China |

83,797,300 |

5.87% |

|

|

| |

Cattle meat (tons) |

United States |

12,047,200 |

19.34% |

62,304,124 |

62.48% |

| |

|

Europe (total) |

11,034,176 |

17.71% |

|

|

| |

|

Brazil |

6,977,480 |

11.20% |

|

|

| |

|

China |

6,235,900 |

10.01% |

|

|

| |

|

Argentina |

2,630,160 |

4.22% |

|

|

| |

Cattle milk (tons) |

Europe (total) |

207,370,015 |

34.58% |

599,615,097 |

68.89% |

| |

|

United States |

87,461,300 |

14.59% |

|

|

| |

|

India |

50,300,000 |

8.39% |

|

|

| |

|

China |

36,022,650 |

6.01% |

|

|

| Russia | 31,895,100 | 5.32% |

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations 2010.

Materials and Methods

Literature review

A review of literature was conducted using the PubMed electronic database to identify clinical and epidemiological reports using key search words that included “bovine” and “zoonoses” and one or more of the following terms—”seroprevalence,” “epidemiology,” “case report,” and “occupational exposure.”

Species database construction

A collection of pathogens was compiled from previously published literature as well as online resources including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the WHO, ProMED, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), and PubMed (Fields et al. 2001, Krauss et al. and Association American Public Health 2003, Heymann 2008, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2011b, World Health Organization 2011a, World Health Organization 2011b, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2011h, National Center for Biotechnology Information 2011, National Institute of Allergy Infectious Diseases 2011).

Results

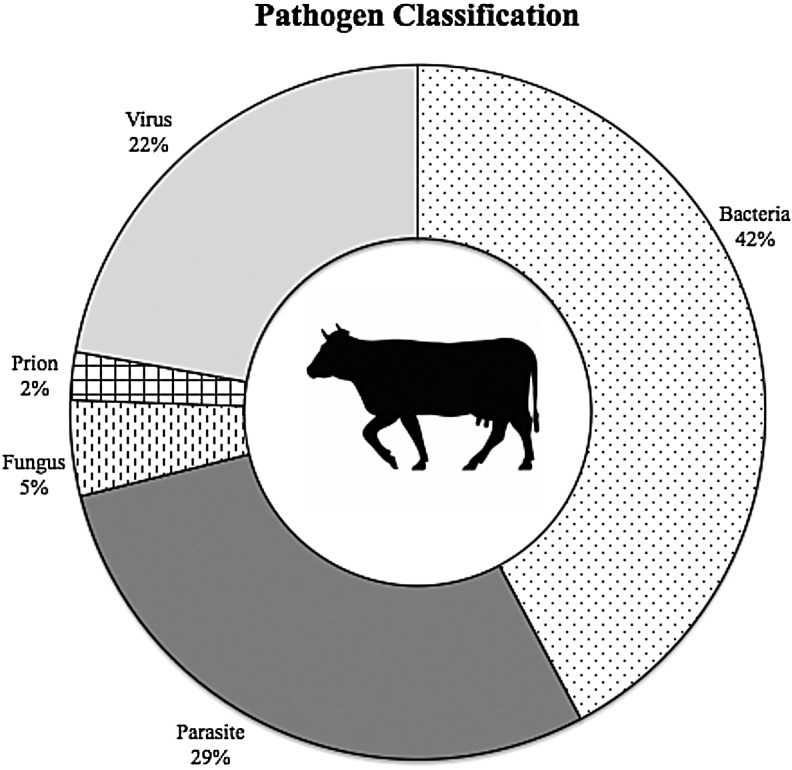

Forty-five bovine zoonotic pathogens were identified in our review. Pathogens known to be capable of infecting humans and domestic cattle are organized in two tables, one table comparing fundamental characteristics (Table 2) and a second table examining the human epidemiology of each pathogen (Table 3). Geographically, bovine zoonoses are evenly dispersed around the world, with the majority (69%) having a worldwide distribution (Fig. 1C, Table 2). Bacterial pathogens represent the largest taxonomic group (42%) of the pathogens, followed by parasitic pathogens (29%), viruses (22%), fungi (5%), and prions (2%). The breakdown of bovine zoonoses by taxonomy is shown in Figure 2. This is consistent with previously reported analyses of zoonotic diseases (Cleaveland et al. 2001, Taylor et al. 2001) and global EID trends (Jones et al. 2008).

Table 2.

Classification of Recognized Bovine Zoonoses

| Pathogen | Taxonomic | Morphology | Baltimore | Bioterrorism | Emerging/Reemerging Status | Disease(s) | Current Geographic Distribution | Case Report References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Actinobacillus lignieresii |

Bacteria |

Gram - coccobacillus |

|

|

|

Actinobacillosis |

Worldwide |

Orda et al. 1980 |

|

Arcanobacterium pyogenes |

Bacteria |

Gram+bacillus |

|

|

|

Arcanobacteriosis |

Worldwide |

Lynch et al. 1998, Reddy et al. 1997 |

|

Bacillus anthracis |

Bacteria |

Gram+bacillus |

|

|

III |

Anthrax |

Worldwide |

Cinquetti et al. 2009, Doganay et al. 2010, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2007a, 2010a, 2011a, 2011b, 2011c, 2011d, 2012a, 2012b, 2012k, Kim et al. 2001, Leblebicoglu et al. 2006, Lester et al. 1997, Schwartz et al. 2002, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2000, 2001, 2010 |

|

Borrelia burgdorferi |

Bacteria |

No Gram classification spirochete |

|

|

|

Lyme disease |

Worldwide |

|

|

Brucella abortus Brucella melitensis |

Bacteria |

Gram - coccobacillus |

|

|

III |

Brucellosis |

Worldwide |

International Society for Infectious Diseases 2007b, 2007c, 2008a, 2009a, 2010b, 2010c, 2011 e, Mudaliar et al. 2003, Park et al. 2009 |

|

Burkholderia pseudomallei |

Bacteria |

Gram - bacillus |

|

|

III |

Melioidosis |

Worldwide |

|

|

Campylobacter fetus Campylobacter jejuni |

Bacteria |

Gram - corkscrew |

|

|

III (C. jejuni) |

Campylobacteriosis |

Worldwide |

Altekruse et al. 1999, Gilpin et al. 2008, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2007d, 2007e, 2007f, 2008d, 2009b, 2009c, 2010d, 2010e, 2010f, 2011f, 2012c |

|

Clostridium difficile |

Bacteria |

Gram+bacillus |

|

|

|

Clostridial disease |

Worldwide |

|

|

Coxiella burnetii |

Bacteria |

Gram - coccobacillus |

|

|

III |

Q fever |

Worldwide |

Bosnjak et al. 2010, Kobbe et al. 2007, McQuiston et al. 2002, Whitney et al. 2009 |

| Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus |

Virus |

enveloped, spherical |

V |

|

III |

Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever |

Africa, Middle East, Asia, and most of Europe |

Hassanein et al. 1997, Swanepoel et al. 1985 |

|

Cryptosporidium spp. |

Parasite |

|

|

|

III |

Cryptosporidiosis |

Worldwide |

Hunter et al. 2004, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2010j, Lengerich et al. 1993, Miron et al. 1991 |

|

Dermatophilus congolensis |

Bacteria |

Gram+cocci |

|

|

|

Dermatophilosis |

Worldwide |

|

|

Dicrocoelium dendriticum Dicrocoelium hospes |

Parasite |

|

|

|

|

Dicrococeliasis |

Europe, Africa, Australia, North America, Asia |

Amor et al. 2011 |

|

Entamoeba histolytica |

Parasite |

|

|

|

III |

Amoebic dysentery |

Worldwide |

|

|

Escherichia coli |

Bacteria |

Gram - bacillus |

|

|

III |

Hemolytic uremic syndrome Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura Hemorrhagic colitis |

Worldwide |

International Society for Infectious Diseases 1998, 2005a, 2005b, 2006a, 2006b, 2006c, 2007g, 2010g, 2012g, 2012h, Parry et al. 1995, Renwick et al. 1993, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2002, Waguri et al. 2007 |

|

Fasciola spp. |

Parasite |

|

|

|

|

Fascioliasis |

Worldwide |

|

|

Giardia intestinalis |

Parasite |

|

|

|

III |

Giardiasis |

Worldwide |

|

|

Gongylonema pulchrum |

Parasite |

|

|

|

|

Gongylonemiasis |

Worldwide |

Thompson et al. 2002 |

| Kyasanur Forest disease virus |

Virus |

enveloped, spherical |

IV |

|

III |

Tick-borne hemorrhagic fever |

Asia |

|

|

Leptospira spp. |

Bacteria |

Gram - spirochete |

|

|

|

Leptospirosis |

Worldwide |

Cacciapuoti et al. 1987, Kariv et al. 2001 |

|

Listeria monocytogenes |

Bacteria |

Gram+bacillus |

|

|

III |

Listeriosis |

Worldwide |

|

|

Mammomonogamus spp. |

Parasite |

|

|

|

|

Mammomonogamiasis |

Caribbean, Asia, South America |

Cain et al. 1986, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2007, McLauchlin et al. 1994, Regan et al. 2005 |

|

Microsporum spp. |

Fungus |

|

|

|

III |

Microsporosis (Ringworm) |

Worldwide |

|

|

Mycobacterium tuberculosis Mycobacterium bovis |

Bacteria |

No Gram classification bacillus |

|

|

III |

Tuberculosis |

Worldwide |

Bayraktar et al. 2011a, Bayraktar 2011b, Cvetnic et al. 2007, De la Rua-Domenech 2006, D'Amore et al. 2010, Fritsche et al. 2004, Ingram et al. 2010, Kubica et al. 2003, Ocepek et al. 2005, Prodinger et al. 2002, Shrikrishna et al. 2009, Tar et al. 2009, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2005, de Kantor et al. 2008 |

| Parapoxvirus |

Virus |

enveloped, brick-shaped |

I |

|

|

Bovine papular stomatitis virus Pseudocowpox Orf |

Worldwide |

|

| Prion |

Prion |

|

|

|

III |

Bovine spongiform encephalopathy new variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease |

Europe, Israel, Japan, potentially others |

|

| Rabies virus |

Virus |

enveloped, cylindrical |

V |

|

III |

Rabies |

Worldwide |

International Society for Infectious Diseases 2012i |

| Rift Valley fever virus |

Virus |

enveloped, spherical |

V |

|

III |

Rift Valley fever |

Africa, Saudi Arabia, Yemen, possibly others |

District et al. 2007 |

| Ross River virus |

Virus |

enveloped, spherical |

IV |

|

III |

Ross River fever |

South America, Australia, New Zealand |

|

|

Salmonella spp. |

Bacteria |

Gram - bacillus |

|

|

III |

Salmonellosis |

Worldwide |

|

| Sarcocystis |

Parasite |

|

|

|

|

Sarcosporidiosis |

Worldwide |

Bemis et al. 2007, Hendriksen et al. 2004, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2003, 2007i, 2007j, 2010h, 2010i, Lazarus et al. 2007, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2002 |

|

Schistosoma spp. |

Parasite |

|

|

|

|

Schistosomiasis |

Africa, Middle East, Caribbean, South America, Asia |

|

|

Shigella spp. |

Bacteria |

Gram - bacillus |

|

|

III |

Shigellosis |

Worldwide |

International Society for Infectious Diseases 2005c |

|

Staphylococcus aureus |

Bacteria |

Gram+staphylococci |

|

|

II |

Staphylococcal disease |

Worldwide |

Grinberg et al. 2004, Moritz et al. 2011, van Cleef et al. 2011 |

|

Streptococcus spp. |

Bacteria |

Gram+streptococci |

|

|

II |

Streptococcus |

Worldwide |

|

|

Taenia saginata |

Parasite |

|

|

|

|

Taeniasis |

Worldwide |

|

| Tick-borne encephalitis virus |

Virus |

enveloped, icosahedral |

IV |

|

III |

Central European encephalitis Russian spring-summer encephalitis |

Europe, Asia |

Public Health Laboratory Service 1994, Tappe et al. 2004 |

|

Toxoplasma gondii |

Parasite |

|

|

|

II |

Toxoplasmosis |

Worldwide |

|

|

Trichophyton spp. |

Fungus |

|

|

|

|

Trichophytosis (Ringworm) |

Worldwide |

|

|

Trichostrongylus spp. |

Parasite |

|

|

|

|

Trichostrongylidiasis |

Worldwide |

Ming et al. 2006, Silver et al. 2008 |

|

Trypanosoma brucei gambiense Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense |

Parasite |

|

|

|

|

African animal trypanosomiasis Human african trypanosomiasis/sleeping sickness |

Africa |

|

| Vaccinia virus Cowpox virus |

Virus |

enveloped, brick-shaped |

I |

|

|

Vaccinia, Cowpox |

Worldwide (excluding the US) |

|

| Vesicular stomatitis virus |

Virus |

enveloped, helical |

V |

|

|

Vesicular stomatitis |

Central and South America |

Baxby et al. 1994, Bhanuprakash et al. 2010, Essbauer et al. 2010, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2007k, 2011g, Megid et al. 2008, Nitsche et al. 2007, Pelkonen et al. 2003, Schnurrenberger et al. 1980, Schupp et al. 2001, Singh et al. 2007, Trindade et al. 2009, Wienecke et al. 2000, de Souza Trindade et al. 2007 |

| Wesselsbron virus |

Virus |

enveloped, spherical |

IV |

|

|

Wesselsbron fever |

Central and South America |

|

| Yersinia pseudotuberculosis Yersinia enterocolitica | Bacteria | Gram - bacillus |  |

III | Yersiniosis | Worldwide | Greenwood et al. 1990, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2007l, Nowgesic et al. 1999, Tacket et al. 1984 |

Biothreat category based on the CDC classification (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2011a); Emerging/Reemerging status based on the NIAID classification (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases 2011).

= Category A,

= Category A,  = Category B,

= Category B,  = Category C

= Category C

Table 3.

Human epidemiological factors of recognized bovine zoonotic pathogens

| |

|

|

|

System potentially affected |

|

|

|

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pathogen | Incubation period | Potential transmission routes | Cardiovascular | Pulmonary | Gastrointestinal | Cutaneous | Ocular | Neurological | Diagnosis | Treatment/vaccine availability | Mortality | ||

|

Actinobacillus lignieresii |

Hours to days |

|

Cutaneous |

• |

• |

• |

• |

• |

• |

ICS |

antibiotics |

|

up to 30% (if untreated) |

|

Arcanobacterium pyogenes |

Hours to days |

|

Cutaneous |

• |

• |

|

• |

• |

• |

IC |

antibiotics |

|

Rare |

|

Bacillus anthracis |

Varies with exposure route |

|

Cutaneous, Ingestion, Inhalation, Vector-borne |

• |

• |

• |

• |

|

• |

ICP |

antibiotics |

|

Varies with exposure route |

|

Borrelia burgdorferi |

1–30 days |

|

Vector-borne |

• |

|

|

• |

|

• |

ICSP |

antibiotics, supportive therapy |

|

Rare |

|

Brucella abortus Brucella melitensis |

Weeks to months |

|

Cutaneous, Ingestion, Inhalation |

• |

• |

• |

• |

• |

• |

ICSP |

antibiotics |

|

<2% (endocarditis) |

|

Burkholderia pseudomallei |

Days to months |

|

Cutaneous, Ingestion, Inhalation |

• |

• |

• |

• |

|

• |

ISP |

antibiotics |

|

up to 20% |

|

Campylobacter fetus Campylobacter jejuni |

3–5 days |

|

Ingestion |

• |

|

• |

|

|

• |

ICSP |

antibiotics, supportive therapy |

|

Rare |

|

Clostridium difficile |

12–36 hours |

|

Ingestion, Cutaneous |

• |

• |

• |

• |

• |

• |

ICSP |

antitoxin, supportive therapy |

|

5–10% |

|

Coxiella burnetii |

2–3 weeks |

|

Inhalation, Ingestion, Vector-borne |

• |

• |

• |

|

|

• |

ICSP |

antibiotics |

|

up to 65% in chronic cases |

| Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus |

Varies with exposure |

|

Cutaneous, Ingestion, Vector-borne, Inhalation* |

• |

• |

• |

• |

• |

• |

SP |

supportive |

|

9–50% |

|

Cryptosporidium spp. |

1–12 days |

|

Ingestion, Inhalation* |

|

• |

• |

|

|

|

ISP |

antiparasitic/antiretrovirals |

|

Rare |

|

Dermatophilus congolensis |

Hours to days |

|

Cutaneous, Vector-borne |

|

• |

• |

• |

|

|

ICSP |

antibiotics |

|

None reported |

|

Dicrocoelium dendriticum Dicrocoelium hospes |

Unknown |

|

Ingestion |

|

|

• |

|

|

|

ISP |

antiparasitic therapy (praziquantel) |

|

None reported |

|

Entamoeba histolytica |

2–6 weeks |

|

Ingestion, Vector-borne |

• |

• |

• |

• |

|

• |

ICSP |

antiparasitic therapy (metronidazole) |

|

up to 30% (abscesses) |

|

Escherichia coli |

1–8 days |

|

Ingestion, Inhalation*, Vector-borne* |

|

|

• |

• |

|

• |

ICSP |

Antibiotics, supportive therapy, dialysis, blood transfusion |

|

up to 10% (HUS cases) up to 50% (TPP cases) |

|

Fasciola spp. |

Days to months |

|

Ingestion |

|

• |

• |

• |

|

• |

ISP |

antiparasitic therapy (triclabendazole) |

|

Rare |

|

Giardia duodenalis |

1–25 days |

|

Ingestion, Vector-borne* |

|

|

• |

|

|

|

ISP |

supportive therapy, antibiotics |

|

Rare |

|

Gongylonema pulchrum |

Weeks |

|

Ingestion |

|

|

• |

• |

|

|

IP |

removal, antihelminthic (albendazole) |

|

Rare |

| Kyasanur Forest disease virus |

3–8 days |

|

Vector-borne, Ingestion |

• |

|

• |

|

|

• |

ISP |

Supportive treatment only |

|

3–5% |

|

Leptospira spp. |

2–30 days |

|

Ingestion, Cutaneous |

• |

• |

• |

• |

|

• |

ICSP |

antibiotics |

|

up to 10% |

|

Listeria monocytogenes |

3 weeks |

|

Ingestion, Cutaneous, Vertical |

• |

• |

• |

• |

|

• |

ICSP |

antibiotics, supportive therapy |

|

30–35% |

|

Mammomonogamus spp. |

6–11 days |

|

Ingestion |

|

• |

• |

|

|

|

I |

removal, antihelminthic therapy |

|

Rare |

|

Microsporum spp. |

Days to weeks |

|

Cutaneous |

|

• |

• |

• |

|

|

ICSP |

antifungal therapy |

|

None reported |

|

Mycobacterium spp. |

Months to years |

|

Inhalation, Ingestion, Cutaneous |

|

• |

• |

• |

|

• |

Skin test |

antibiotics |

|

19% |

| Parapoxvirus |

Varies with type |

|

Cutaneous |

|

|

|

• |

|

• |

ICSP |

supportive treatment only |

|

None |

| Prion |

Years |

|

Ingestion*, Vertical*, Vector-borne*, Iatrogenic* |

|

|

|

|

|

• |

ISP |

supportive treatment only |

|

100% |

| Rabies virus |

1 to 3 months |

|

Inhalation, Cutaneous |

|

|

• |

|

|

• |

ISP |

pre/post-exposure prophylaxis, immunoglobulin |

|

100% (if untreated) |

| Rift Valley fever virus |

3–7 days |

|

Vector-borne, Cutaneous, Inhalation |

|

|

• |

|

|

• |

IC |

supportive treatment only |

|

<1% |

| Ross River virus |

7–9 days |

|

Vector-borne |

• |

|

|

|

|

|

ICSP |

supportive treatment only |

|

None reported |

|

Salmonella spp. |

5–72 hours |

|

Ingestion |

|

|

• |

|

|

|

ICSP |

supportive therapy, antibiotics |

|

1–15% |

| Sarcocystis |

Hours to days |

|

Ingestion |

|

|

• |

|

|

|

I |

supportive treatment only |

|

None reported |

|

Schistosoma spp. |

1–2 months |

|

Cutaneous |

|

|

• |

• |

|

• |

ISP |

praziquantel |

|

<1% |

|

Shigella spp. |

Hours to days |

|

Ingestion |

|

|

• |

• |

|

• |

ISCP |

antibiotics |

|

<1% |

|

Staphylococcus aureus |

Highly variable |

|

Cutaneous, Ingestion, Inhalation |

• |

• |

• |

• |

|

• |

ICSP |

antibiotics, supportive therapy |

|

Varies with infection type |

|

Streptococcus spp. |

Hours to days |

|

Ingestion, Inhalation, Cutaneous (varies with species) |

• |

• |

• |

• |

|

• |

ICSP |

antibiotics |

|

up to 29% |

|

Taenia saginata |

Days to years |

|

Ingestion |

|

|

• |

|

|

|

ISP |

praziquantel, niclosamide |

|

None reported |

| Tick-borne encephalitis virus |

7–14 days |

|

Vector-borne, Ingestion, Cutaneous, Vertical |

|

|

• |

|

|

• |

ICSP |

supportive treatment only |

|

1–2% |

|

Toxoplasma gondii |

10–23 days |

|

Ingestion, Inhalation, Vector-borne |

• |

• |

• |

|

• |

• |

ICSP |

antibiotics, antiparasitic therapy (pyrimethamine, sulfadiazine) |

|

up to 84% (immunocompromised) |

|

Trichophyton spp. |

2–4 weeks |

|

Cutaneous, Vector-borne* |

|

|

|

• |

|

|

ICSP |

antifungual therapy |

|

None reported |

|

Trichostrongylus spp. |

Unknown |

|

Ingestion |

|

|

• |

|

|

|

ICP |

pyrantel pamoate, mebendazole, albendazole |

|

None reported |

|

Trypanosoma brucei gambiense Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense |

Weeks up to a year |

|

Vector-borne, Cutaneous, Vertical |

• |

|

|

• |

|

• |

ICSP |

Stage I: pentamidine, suramin Stage II: melarsoprol, eflornithine |

|

100% (if untreated) |

| Vaccinia virus Cowpox virus |

Days up to two weeks |

|

Vector-borne, Cutaneous |

|

|

|

• |

|

• |

ICSP |

antivirals, supportive treatment |

|

Rare |

| Vesicular stomatitis virus |

3–4 days |

|

Vector-borne, Cutaneous, Inhalation* |

|

• |

|

• |

• |

|

ICSP |

supportive treatment only |

|

None reported |

| Wesselsbron virus |

2–4 days |

|

Vector-borne, Inhalation |

• |

• |

|

• |

• |

• |

ICSP |

supportive treatment only |

|

None reported |

| Yersinia pseudotuberculosis Yersinia enterocolitica | 3–7 days |  |

Inhalation, Cutaneous | • | • | • | • | • | ICSP | antibiotics |  |

up to 60% (if untreated) | |

= Human-to-human transmission

= Human-to-human transmission

= Vaccine available;

= Vaccine available;  = Vaccine not available for humans

= Vaccine not available for humans

Diagnosis: I = Inoculation, C = Culture, S = Serology, P = PCR

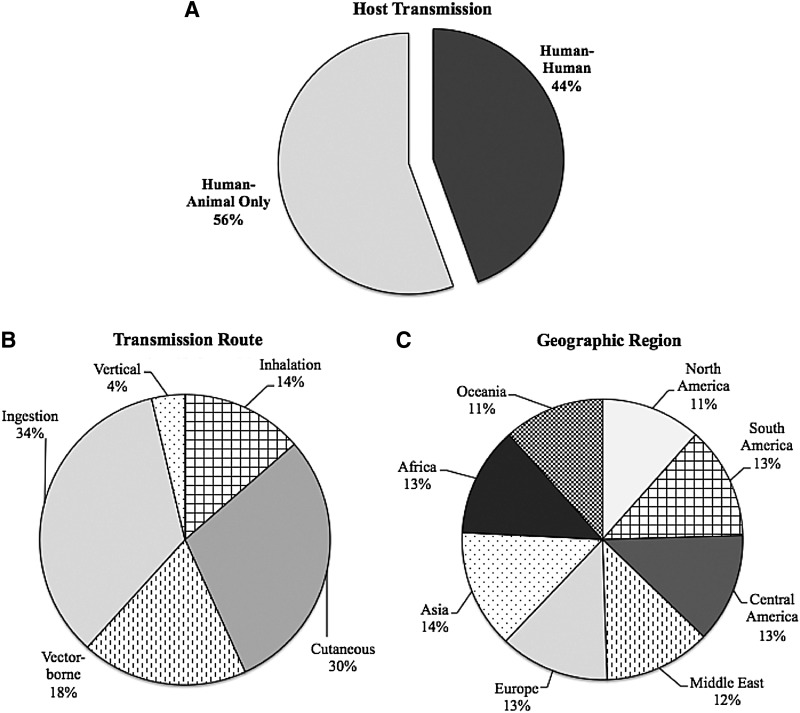

FIG. 1.

Characteristics of cattle zoonotic pathogens. (A) Host transmission: Percentage of cattle zoonotic pathogens for which human-to-human transmission occurs. (B) Transmission route: Percentage of cattle zoonotic pathogens able to be transmitted by various routes of exposure. (C) Geographic region: Percentage of cattle zoonotic pathogens found in each geographic region. (Data aggregated from Tables 2 and 3.)

FIG. 2.

Cattle zoonotic agent by microbiological category. (Data aggregated from Table 2.)

Further categorical analysis was conducted on bacterial and viral species. Among bacteria, 10 (53%) were Gram-negative, seven (37%) were Gram-positive, and two (10%) had no Gram classification. Morphologically, 13 (68%) of the species were rod-shaped bacilli, three (16%) were round cocci, and three (16%) displayed alternate morphologies (spirochetes and corkscrew). Likewise, viruses were classified based on the type of genome and method of replication used (Baltimore classification). Two (20%) were double-stranded DNA viruses (Group I), four (40%) were positive-sense RNA viruses (Group IV), and four (40%) were negative-sense RNA viruses (Group V).

Bovine zoonoses are among pathogens listed as EIDs. Currently the NIAID recognizes 25 (56%) bovine zoonoses as emerging or re-emerging diseases of interest (National Institute of Allergy Infectious Diseases 2011). Of the emerging bovine zoonotic pathogens, 13 (52%) are bacteria, six (24%) are viruses, four (16%) are parasites, one (4%) is fungal, and one (4%) is a prion (Table 2). Pathogens recognized in this list often pose ongoing health problems and have the potential to create a significant impact on the overall health of the community. Similarly, the CDC pays particular attention to diseases that have the ability to be used as biological weapons based on their ability to create human disease and public fear (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2011a). Given the importance of cattle, not only in terms of human health but also to the food supply, a number of bovine zoonoses have been classified as potential bioterrorism agents. Twenty-four (53%) of the recognized cattle zoonotic pathogens are on CDC's bioterrorism list. Category A pathogens are high-priority pathogens that pose the greatest risk to national security. Similarly, category B pathogens pose a moderate risk to national security. A third group, category C, is composed of pathogens that are emerging and could be engineered to be used as biological weapons. Of the 24 cattle zoonotic pathogens, two (8%) are category A, 16 (67%) are category B agents, and six (25%) are category C agents (Table 2).

In this report, we summarize the clinical presentation of known bovine zoonotic agents by the human organ system affected. We have also included 135 case reports of human zoonotic disease known or highly suspected to be a result of exposure to cattle identified in the literature (Table 2). Many zoonoses, however, may be undetected or underreported, preventing an accurate assessment of the impact of human–cattle interactions on public health. Readers are encouraged to refer to Tables 2 and 3 for details on the characteristics and epidemiology of these pathogens.

Pulmonary

Several bovine zoonoses of serious public health concern cause pulmonary infections in humans, perhaps the most important being zoonotic tuberculosis caused by Mycobacterium bovis (Abalos and Retamal 2004, Fritsche et al. 2004, Davies 2006, De la Rua-Domenech 2006, de Kantor et al. 2008, Shrikrishna et al. 2009, Ingram et al. 2010, Torgerson and Torgerson 2010) or rarely M. tuberculosis (Ocepek et al. 2005, Bayraktar et al. 2011a). We also identified reports involving both human and bovine cases confirmed or highly suspected to be a result of zoonotic transmission of M. caprae (Prodinger et al. 2002, Cvetnic et al. 2007, Tar et al. 2009, Bayraktar et al. 2011b). Bovine tuberculosis has largely been eliminated from developed countries with strong animal disease control programs, but is still a serious zoonotic threat in other areas of the world. Most human M. bovis infections occur after drinking or handling unpasteurized milk that is contaminated, but agricultural workers may also become infected by inhaling bacteria that are aerosolized via coughing of infected cattle (Moda et al. 1996). Humans can also present with urogenital infections of M. bovis (Ocepek et al. 2005). In addition to infected respiratory secretions, M. bovis shedding in the urine may serve as a potential reverse zoonosis from humans to cattle. This may be particularly important for closed herds that do not have wildlife exposure or otherwise exposure to potential sources of infection. Bovine tuberculosis is likely underdiagnosed in regions of the world where it has not been controlled, because it is clinically indistinguishable from nonzoonotic tuberculosis and requires specialized laboratory expertise and equipment for diagnosis.

Similarly, Q fever caused by the rickettsial parasite Coxiella burnetii, primarily causes an influenza-like illness in humans. Among the less common complications of Q fever that have been documented are atypical pneumonia, hepatitis, and endocarditis (Arricau-Bouvery and Rodolakis 2005). C. burnetii is shed in very high numbers in birth fluids and the placenta of infected animals as well as in the milk (Loftis et al. 2010) and is extremely hardy in the environment; people are most often infected by direct contact with infected fluids or by inhalation of contaminated dust. People at increased risk of Q fever include livestock handlers, especially veterinarians or persons providing obstetrical assistance to cows, those who live near or visit livestock facilities, those who consume unpasteurized milk, and those who have preexisting heart disease or are immunocomprimised (Abe et al. 2001, McQuiston and Childs 2002, Kobbe et al. 2007, Whitney et al. 2009, Bosnjak et al. 2010).

Accurate diagnosis and epidemiologic analysis of bovine zoonotic respiratory infections causing influenza-like illness may be hampered due to a lack of specific diagnostics and the often-indistinguishable clinical presentation from common human respiratory agents, such as influenza, coronavirus, parainfluenza virus, respiratory syncytial virus, adenovirus, enterovirus, and metapneuomovirus (Zhang et al. 2011). With similarity in clinical symptoms, ascertaining the true incidence and prevalence of bovine zoonotic respiratory infections will require specifically designed large-cohort studies of at-risk populations. If zoonotic respiratory pathogens of bovine origin develop or have developed the ability to spread as easily as other known human respiratory pathogens, we may very well be underestimating the morbidity and mortality associated with these infections. Differential diagnoses of agricultural workers with a history of cattle exposure should include the traditional human pathogens as well as the following bovine zoonotic pathogens: Bacillus anthracis, Brucella spp., C. burnetti, Listeria monocytogenes, and Mycobacterium spp.

Gastrointestinal

Gastrointestinal infections are among the most common cattle zoonoses, in part because of their ubiquitous nature (Tables 2 and 3). Outbreaks involving contaminated cattle products have been well documented for a number of bacterial species, including enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli (Renwick et al. 1993, Parry et al. 1995, International Society for Infectious Diseases 1998, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2002, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2005a, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2005b, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2006a, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2006b, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2006c, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2007g, Waguri et al. 2007, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2010g, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2012e, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2012f, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2012g, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2012h), Salmonella spp. (International Society for Infectious Diseases 2003, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2007i, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2007j, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2008, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2010h, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2010i), Listeria spp. (International Society for Infectious Diseases 2007h), Streptococcus spp. (Public Health Laboratory Service 1994), Shigella spp. (International Society for Infectious Diseases 2005c), Campylobacter spp. (Altekruse et al. 1999, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2007e, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2007f, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2008b, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2009b, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2009c, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2007d, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2010d, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2010e, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2010f, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2011f, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2012j), B. anthracis (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2000, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2007a, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2010a, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2011a, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2011b, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2011c, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2011d, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2012a, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2012b), and Yersinia spp. (Tacket et al. 1984, Greenwood and Hooper 1990, Nowgesic et al. 1999, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2007l). A foodborne outbreak involving one of these pathogens is likely to originate from mishandling or inadequate preparation of meat or dairy products. Recent studies have shown the presence of Salmonella, L. monocytogenes, and E. coli O157:H7 in inline filters and bulk tank milk samples across the United States (Jayarao and Henning 2001, Jayarao et al. 2006, Van Kessel et al. 2011) and in fresh cheeses popular in Mexico (Torres-Vitela et al. 2012). Among these bacterial species, Listeria and Yersinia spp. are unique in that these bacteria are cold tolerant and able to grow under cooler temperatures in milk that has been inadequately pasteurized. Not surprisingly, unpasteurized milk and cheese consumption are associated with the majority of documented outbreaks (International Society for Infectious Diseases 1998, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2003, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2005a, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2005c, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2006a, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2006b, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2006c, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2007c, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2007d, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2007e, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2007f, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2007g, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2007h, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2007i, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2007j, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2007l, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2008b, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2009b, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2009c, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2010d, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2010e, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2010f, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2010h, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2010i, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2011c, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2011f, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2012b, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2012c, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2012d, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2012e, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2012f, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2012j). While local laws have been adopted in some areas in an effort to prevent such outbreaks, many people in both the United States and around the world preferentially consume these products.

Foodborne disease outbreaks are not confined to developing countries, because many of the documented cases occur in the United States or other countries with advanced public health networks. In fact, the CDC estimates that there are approximately 48 million cases of domestically acquired foodborne illness in the United States every year (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2012), the majority of which go unreported. Even when cases are reported, the source of the infection is often never determined because foodborne zoonoses may originate from many animals (e.g., shellfish, pigs, poultry, cattle). Therefore, the true contribution of bovine pathogens to the burden of foodborne illness is unknown.

Gastrointestinal illnesses resulting from infection with bacterial zoonotic pathogens are not isolated to the consumption of cattle products. Parasitic infections resulting from fecal–oral transmission of Cryptosporidium spp. (Miron et al. 1991, Lengerich et al. 1993, Hunter et al. 2004, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2010d) and Giardia spp. (Thompson 2002) from cattle have been confirmed, and drinking contaminated water or handling infected cattle increases the risk of infection. Because both of these parasitic organisms may be transmitted through water, their potential as contaminants in drinking water remains an important public health issue for water authorities. The role that animals, both wildlife and livestock, play as a zoonotic reservoir of infection, however, remains controversial (Hunter and Thompson 2005).

Our review of the literature revealed a number of unusual cases of nonfoodborne zoonotic transmission of B. anthracis (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2010), Campylobacter spp. (Gilpin et al. 2008), E. coli (Renwick et al. 1993, Parry et al. 1995, Waguri et al. 2007), and Salmonella spp. (Hendriksen et al. 2004, Bemis et al. 2007) that resulted in gastrointestinal illness in humans. These events, while likely representing only rare incidents, reveal the increased potential of acquisition of gastrointestinal zoonotic disease by agricultural workers as a result of their exposure to infected cattle. This segment of the population is more at risk for infection with bovine zoonotic agents, and also represents a bridging population where human and animal pathogens can potentially shift and adapt to novel ecological environments.

Cutaneous

Bovine zoonotic infections affecting the skin and underlying cutaneous tissues may have the longest history of recognition (Koch 1876). Symptoms are generally mild but distinctive, ranging from itching, redness, and swelling to more severe rashes (as with the characteristic black ulcers of anthrax and the “bull's eye” rash of Lyme disease) and lesions (characteristic with poxviruses). Not surprisingly, the most commonly reported agents include cutaneous anthrax (Doganay and Aygen 1997, Lester et al. 1997, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2001, Schwartz 2002, Cinquetti et al. 2009), and poxvirus lesions (cowpoxvirus and parapoxvirus, such as pseudocowpox and bovine papular stomatitis virus) (Schnurrenberger et al. 1980, Baxby et al. 1994, Wienecke et al. 2000, Schupp et al. 2001, Pelkonen et al. 2003, de Souza Trindade et al. 2007, Nitsche and Pauli 2007, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2007k, Singh et al. 2007, Trindade et al. 2009, Bhanuprakash et al. 2010, Essbauer et al. 2010, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2011g). Anthrax, caused by B. anthracis, is an important disease of domestic herbivores, including cattle, and occurs throughout the world. Human cutaneous infections are usually occupational in nature and associated with exposure to contaminated hides, hair, blood, and meat.

Again, during our review of the literature, a number of unusual bacterial cutaneous infections were discovered involving Listeria spp. (Cain and McCann 1986, McLauchlin and Low 1994, Regan et al. 2005), Salmonella spp. (Lazarus et al. 2007), Staphylococcus aureus (Grinberg et al. 2004), and Streptococcus spp. (Tappe et al. 2004), as well as potentially emerging fungal pathogens, such as Trichophyton spp. (Ming and Bulmer 2006, Silver et al. 2008). As before, in each case the incident was related to an occupational exposure involving an infected bovine. We are unable to discern if these cases are simply rare transmission events, an underreporting of true incidence, or the possible sign of emerging pathogens. Focused surveillance activities would allow for a more definitive conclusion.

Another concerning topic for public health—drug-resistant pathogens—emerged during the literature review of cutaneous zoonotic infections. Numerous recent publications (2008–2011) have documented the presence of livestock-associated methicillin-resistant S. aureus (LaMRSA), particularly of sequence type 398 (ST398) (Nemati et al. 2008, Golding et al. 2010, Meemken et al. 2010, Moodley et al. 2010, Vanderhaeghen et al. 2010, Hallin et al. 2011, Moritz and Smith 2011, Smith and Pearson 2011, van Cleef et al. 2011a, Wassenberg et al. 2011). The epidemiology of methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) has changed dramatically over the last decade (Layton et al. 1995, Smith and Pearson 2011). Initially a nosocomial pathogen, MRSA has become increasingly common in the community regardless of contact with hospitals or other community health care facilities. Strains accounting for a significant number of infections have origins unrelated to nosocomial strains (Huang et al. 2006). Nursing home residents, prisoners, athletes, children, and intravenous drug users are groups commonly associated with community-acquired strains of MRSA. In addition to nosocomial and community-acquired MRSA, a third group has been identified in association with livestock, including cattle, swine, horses, and poultry. LaMRSA was first recognized in cattle (Devriese and Hommez 1975), and a substantial literature exists documenting the economic losses that can result from bovine mastitis, a persistent inflammatory infection of the mammary gland tissue. Prior to the emergence of ST398, sporadic cases of mastitis and bovine milk contamination with MRSA were reported (Holmes and Zadoks 2011). Strains identified were often associated with human lineage, suggesting there is a sustained pathway for transmission of such pathogens. Current information suggests this trend is continuing, with the recent recognition of divergent strains of S. aureus in humans that were previously thought to be bovine-specific (Holmes and Zadoks 2011). Future implications of LaMRSA such as ST398 and other potentially emerging cutaneous pathogens on the health of agricultural workers and on public health overall have yet to be fully considered and warrant further inquiry.

Neurological

Neurological infection may manifest in a variety of ways, creating difficult scenarios for diagnosis and study. Symptoms overlap with those of noninfectious neurological cases, including fatigue, headache, dizziness, loss of mental acuity, photophobia, drowsiness, etc. Cattle are potential carriers of bacterial zoonotic pathogens that can cause such symptoms. Among these, B. anthracis, Brucella spp., and rarely enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC), Leptospira spp., and Borrelia burgdorferi can affect the central nervous system in severe manifestations of neuropathies, meningitis, or encephalitis. Proper detection and early treatment are vital in these cases. There have been documented events of bovine-associated anthrax that have resulted in cases of neurological manifestations, including a common-source outbreak producing two cases of meningoencephalitis and three cases of cutaneous anthrax associated with beef consumption (Kim et al. 2001) as well as an outbreak involving a cluster of cases resulting from contact or consumption of the carcass of a cow (Leblebicoglu et al. 2006). In all three neurological anthrax infections, the patients died.

Alternatively, infectious proteins, known as prions, have been associated with a degenerative neurological disorder known as new variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (nvCJD). There is much that is still unknown surrounding the etiology of this disease. Possible origins of infection have been identified—genetic inheritance, the consumption of contaminated cattle products, or, in some cases, sporadic development. Contact with infected animals and consumption of cattle products, particularly components of the central nervous system, appear to be associated with the development of this disease (Belay and Schonberger 2005). Occupational cattle workers and those that consume cattle products of the neurological system are potentially at greater risk for the development of nvCJD.

Rabies virus is often considered the most prominent zoonotic agent that directly affects the neurological system. Despite having one of the longest-known disease histories, the epidemiology of rabies remains incomplete. Rabies virus varies worldwide from continent to continent, and even within countries (urban vs. sylvatic rabies) (Krauss et al. 2003). Host range is wide in mammals, with bats being a particularly important vector. Clinical disease in humans is acute and almost inevitably fatal without proper prophylaxis or postexposure vaccination. Transmission occurs predominantly via saliva from the bite of an infected animal, but infective virus is secreted in all body fluids including saliva, blood, milk, and urine. While it appears canine species and bats are the most important vectors of zoonotic transmission to humans, cattle are likely the most significant among domesticated livestock (Odontsetseg et al. 2009, World Health Organization 2004). Human cases resulting from bovine exposure were difficult to ascertain from the literature; however, rare events have been documented (Delpietro et al. 2001, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2012i). Close contact with infected animals is therefore the greatest risk factor for infection. After any suspected exposure, vaccination must be administered within 24 h to prevent disease, and ultimately death.

Infections involving rabies and other zoonotic pathogens resulting in neurological pathology are often the most severe cases of the disease with the poorest health outcomes. Treatment options are often limited for these infections once neurological presentation is observed, resulting in high fatality rates. Early diagnosis and treatment is critical to decreasing the morbidity and mortality associated with these infections.

Cardiovascular

Cardiovascular infections resulting from bovine zoonoses vary from mild to severe. Symptoms may include fever, malaise, shortness of breath, chest pain, and less commonly edema, cardiovascular shock, myocarditis, endocarditis, hemolysis, and thrombosis. Bacterial pathogens have included B. anthracis, B. burgdorferi, Brucella spp., Campylobacter spp., C. burnetti, Leptospira spp., L. monocytogenes, and Streptoccocus spp. Generally these infections have resulted in mild, treatable cases. Such infections may occur in agricultural workers with occupational exposure to cattle, as evident by a recent case report of Brucella endocarditis (Park et al. 2009). This report was unable to identify the source of infection, but the patient's past exposure strongly suggests a zoonotic transmission event.

Again, the most serious cardiovascular presentations, due to the lack of treatment options, are caused by viral or parasitic zoonoses. These pathogens are regionally specific but are important considerations in endemic areas. Included in this group are Crimean–Congo hemorrhagic fever (Africa, Middle East, Asia, most of Europe), Kyasanur Forest disease virus (Asia), and Ross River virus (Australia, New Zealand, and other countries of the South Pacific). These pathogens should be considered in the differential diagnosis of cardiovascular disease among agricultural workers and people living in endemic areas, particularly if there is a history of livestock or mosquito exposure.

Systemic infections

Some pathogens do not have symptoms related to one human organ system and are therefore considered systemic infections. Bacterial pathogens such as Leptospira spp., Brucella spp., and very rarely Arcanobacterium pyogenes (or Trueperella pyogenes) and Actinobacillus lignieresii cause a systemic clinical presentation. Viral pathogens such as Rift Valley Fever virus and Crimean–Congo hemorrhagic fever are also generally considered to be systemic zoonotic infections.

Leptospirosis is an acute disease that affects humans and a wide range of animals. Clinical presentation varies, because the bacteria are able to invade any organ system, and asymptomatic infections are known to occur. The bacteria are spread through urine and other bodily fluids of infected animals. Human infections from Leptospira spp. generally occur through direct contact with broken skin during exposures involving swimming, walking with bare feet, or agricultural work with infected animals. Ingestion of contaminated water or unpasteurized milk may also serve as routes of infection. Cattle have been shown to be among one of the most commonly associated animals with zoonotic transmission of leptospirosis (Cacciapuoti et al. 1987, Ashford et al. 2000, Kariv et al. 2001, Jansen et al. 2005, Storck et al. 2008).

Brucellosis, caused by Brucella abortus or B. melitensis, is also an important bacterial zoonosis that is usually associated with consumption of unpasteurized cheese and milk (International Society for Infectious Diseases 2007c). Brucella spp. can cause an influenza-like illness and sometimes pneumonia in humans as well as other serious complications, such as meningitis, septicemia, osteomyelitis of the vertebra, and endocarditis. While brucellosis has been controlled in many countries that have strong animal disease control programs, outbreaks still occur in many countries in eastern Europe as well as in Russia (International Society for Infectious Diseases 2007b, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2007c, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2008a, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2009a, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2010b, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2010c, International Society for Infectious Diseases 2011e). Dairy workers, shepherds, veterinarians, abattoir workers, and animal husbandry personnel are among those most at risk for infection.

Viral hemorrhagic fevers (Crimean–Congo hemorrhagic fever virus and Rift Valley Fever virus) present systemic infections that include backache, nausea, vomiting, and a characteristic hemorrhagic fever sometimes seen in recurrent or biphasic courses. Crimean–Congo hemorrhagic fever virus is transmitted to humans by infected ticks or livestock. Rift Valley fever virus is similarly acquired through handling of infected animals or exposure to mosquito vectors in connection with enzootic or epizootic infections of livestock (Pourrut et al. 2010). Occupational exposure involving slaughter and parturition of infected animals along with exposure to environments that contain potentially affected vectors of disease are important risk factors for infection with hemorrhagic fevers. For example, the first cases of Crimean–Congo hemorrhagic fever identified were a fatal infection in a child bitten by a tick and two nonfatal infections in farmers who handled livestock: One slaughtered a sheep and the other had dehorned and castrated calves (Gear et al. 1982, Swanepoel 1983, Swanepoel et al. 1985). The ease of transmission and use of animal reservoirs and vectors complicate prevention strategies. Animal surveillance should be considered a crucial component in public health strategies to prevent humans from being sentinel hosts during Rift Valley fever outbreaks. Prompt treatment of infections along with public health control measures that include vector control and animal vaccination are critical in containing outbreaks resulting from these systemic infections.

Discussion

The majority of pathogens that cause disease in humans are zoonotic (Cleaveland et al. 2001, Taylor et al. 2001, Woolhouse et al. 2005a). While much is known regarding these pathogens and the resulting disease, the current and future role zoonotic disease transmission plays in public health has yet to be fully explored. Due to the similarity of clinical presentation with nonzoonotic infections, the potential for undiagnosed cases of these pathogens exists. Because physicians, nurses, veterinarians, and other members of public and veterinary health are the front line of defense against infectious disease, we have summarized the known bovine zoonotic agents by clinical presentation in humans. With this framework, we hope to highlight the potential of these pathogens to infect humans as well as to create a useful summary for pubic health professionals, clinicians treating humans and animals, and researchers that highlight the epidemiology of bovine zoonotic pathogens.

The projected worldwide increase in cattle populations is indicative of their substantial role in human life. Interestingly, despite advanced public health systems in the developed world, each of the seven geographic regions studied revealed virtually an equal presence of cattle zoonotic pathogens (Fig. 1C). This is likely a result of a combination of factors. First, the universal presence of cattle around the world coupled with their movement between livestock farms, markets, and abattoirs presents the opportunity for pathogens to adapt to new environments and expand geographically. Transportation of cattle, sometimes millions per year, has not only been shown to contribute to the spread of infectious diseases (Woolhouse et al. 2005b), but has also specifically been implicated in the recent increase in bovine tuberculosis in Great Britain (Gilbert et al. 2005). Second, a significant percentage (44%) of bovine zoonotic pathogens have the ability to transmit from human-to-human (Fig. 1A, Table 3). This number must be interpreted cautiously given that most zoonoses are not highly transmissible within human populations and do not result in major epidemics.

Biological flexibility in host range can be seen in many of the most prevalent infectious diseases. Prominent examples include E. coli, Salmonella, influenza, and rabies virus. Among bovine zoonotic pathogens, bacterial pathogens represented the largest taxonomic group both overall (42%) and among emerging bovine zoonotic pathogens (50%) (Fig. 2, Table 2). This is not surprising given the larger number of zoonotic bacterial species relative to other taxonomic groups (Woolhouse 2005a). Interestingly however, 68% of the bacterial species identified were rod-shaped bacilli. On the basis of our current understanding, inferring the reasons behind potential selection factors of bacterial morphology cannot be stated confidently but warrant further discussion (Mitchell 2002, Young 2007).

Parasitic and viral pathogens also made up a significant proportion of bovine zoonotic pathogens, 29% and 22%, respectively. Although parasites are a significant proportion of zoonotic infections both generally and in terms of bovine zoonoses, they have been shown to be relatively unlikely emerging pathogens (Cleaveland et al. 2001). The authors propose these results may be related to the relative complexity of their life cycles and longer generation times. Viral pathogens, however, were found to be a clear risk factor for disease emergence in humans and animals. In our study of viral bovine zoonoses, 80% contained an RNA genome and represented all of the emerging viral zoonoses (Table 2). This may be best explained by the high mutation rate of RNA viruses, aiding in rapid adaptation to new environments (Horsburgh 1998, Woolhouse 2005c). Another explanation may be the subclinical nature of many of these viruses as well the difficulty in treating them. Few effective antiviral therapies are widely available and used, thus allowing many of these viruses to easily spread to human and animal populations unrestrained.

The propensity of some pathogens to evolve with their rapidly changing environment creates troubling circumstances for future treatment and management strategies of emerging pathogens. The potential high morbidity and mortality rates associated with many cattle zoonotic diseases, such as Rift Valley fever, Crimean–Congo hemorrhagic fever, Q fever, and anthrax, coupled with the negative public impact that can result from an outbreak of these diseases, has garnered extra interest from both governmental and public health agencies. Furthermore, to meet the growing demand for beef and dairy products globally, cattle stocks will likely continue to increase, providing increased opportunities for zoonotic transmission. Both the CDC and NIAID have listed approximately half of all bovine zoonotic pathogens as both biological weapons (52%) and as potential emerging pathogens (50%). Their potential as biological weapons was most recently highlighted in the anthrax attacks that occurred in the United States shortly after September 11, 2001 (Warrick 2010, Federal Bureau of Investigation 2011). The number of cattle is projected to continue to increase worldwide (United States Department of Agriculture: Interagency Agricultural Projections Committee 2011), thus the role and impact cattle play on the future of public health will likely remain compelling.

The recognition of zoonotic pathogens as a vital component of a global health system is essential in the study of infectious diseases. Infectious diseases are not bound by the geographical or international boundaries recognized by humans; they are truly a global issue. Arguably, globalization is aiding these organisms in their quest to find new hosts, both traditional and exotic, and in the diversification of their genetic repertoire due to new selective pressures. This has become increasingly evident in the spread of microbial resistance. It is crucial that environmental, veterinary, and human health sectors work in close collaboration to better our understanding of zoonotic disease ecology and prevention. With the rising rate of contact between humans and cattle, as well as their global movement, establishing a strong epidemiological framework with which to study and monitor these pathogens on a global scale will be essential.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Fiona Maunsell, University of Florida, College of Veterinary Medicine, for her expertise and constructive comments in developing this manuscript. We would also like to thank the Department of Defense for financial support during the research and writing of this publication.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- Abalos P, Retamal P. Tuberculosis: A re-emerging zoonosis? Rev Sci Tech 2004; 23:583–594 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abe T, Yamaki K, Hayakawa T, Fukuda H, et al. A seroepidemiological study of the risks of Q fever infection in Japanese veterinarians. Eur J Epidemiol 2001; 17:1029–1032.v [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altekruse SF, Stern NJ, Fields PI, Swerdlow DL. Campylobacter jejuni—an emerging foodborne pathogen. Emerg Infect Dis 1999; 5:28–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Veterinary Medical Association One Health: A New Professional Imperative. 2008. Available at https://www.avma.org/KB/Resources/Reports/Pages/One-Health.aspx/ Accessed April28, 2013

- Amor A, Enríquez A. Corcuera MT, Toro C, Herrero D, Baquero M. Is infection by Dermatophilus congolensis underdiagnosed? J Clin Microbiol 2011; 49:449–451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong GL, Conn L A, Pinner R W. Trends in infectious disease mortality in the United States during the 20th century. JAMA 1999; 281:61–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arricau-Bouvery N, Rodolakis A. Is Q fever an emerging or re-emerging zoonosis? Vet Res 2005; 36:327–349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashford DA, Kaiser RM, Spiegel RA, Perkins BA, et al. Asymptomatic infection and risk factors for leptospirosis in Nicaragua. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2000; 63:249–254 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxby D, Bennett M, Getty B. Human cowpox 1969–1993: A review based on 54 cases. Br J Dermatol 1994; 131:598–607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayraktar B, Bulut E, Bariş AB, Toksoy B, et al. Species distribution of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex in clinical isolates from 2007 to 2010 in Turkey: A prospective study. J Clin Microbiol 2011a; 49:3837–3841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayraktar B, Togay A, Gencer H, Kockaya T, et al. Mycobacterium caprae causing lymphadenitis in a child. Pediatr. Infect Dis J 2011b; 30:1012–1013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belay ED, Schonberger LB. The public health impact of prion diseases. Annu Rev Public Health 2005; 26:191–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bemis DA, Craig LE, Dunn JR. Salmonella transmission through splash exposure during a bovine necropsy. Foodborne Pathog Dis 2007; 4:387–390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhanuprakash V, Venkatesan G, Balamurugan V, Hosamani M, et al. Zoonotic infections of buffalopox in India. Zoonoses Public Health 2010; 57:149–155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Board on International Health America's vital interest in global health: Protecting our people, enhancing our economy, and advancing our international interests. Washington DC: National Academy Press, 1997 [Google Scholar]

- Bosnjak E, Hvass a M S W, Villumsen S, Nielsen H. Emerging evidence for Q fever in humans in Denmark: Role of contact with dairy cattle. Clin Microbiol Infect 2010; 16:1285–1288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley R, Liberski P P. Bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE): The end of the beginning or the beginning of the end? Folia Neuropathol 2004; 42(Suppl A):55–68 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacciapuoti B, Vellucci A, Ciceroni L, Pinto A, et al. Prevalence of leptospirosis in man. Pilot survey. Eur J Epidemiol 1987; 3:137–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cain DB, McCann VL. An unusual case of cutaneous listeriosis. J Clin Microbiol 1986; 23:976–977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavirani S. Cattle industry and zoonotic risk. Vet Res Commun 2008; 32(Suppl 1):S19–S24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Human Ingestion of Bacillus Anthracis-Contaminated Meat—Minnesota, August 2000. JAMA 2000; 49:813–816 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Human anthrax associated with an epizootic among livestock—North Dakota, 2000. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2001; 50:677–680 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Multistate outbreak of Escherichia coli O157:H7 infections associated with eating ground beef—United States, June–July 2002. Morb Mortal WklyRep 2002; 51:637–639 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control Rift Valley fever outbreak-Kenya, November 2006–January 2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2007; 56:73–76 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Outbreak of multidrug-resistant Salmonella enterica serotype Newport infections associated with consumption of unpasteurized Mexican-style aged cheese—Illinois, March 2006–April 2007. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2008; 57:432–435 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Gastrointestinal Anthrax after an Animal-Hide Drumming Event—New Hampshire and Massachusetts, 2009. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2010; 59:872–877 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Bioterrorism Agents/Diseases: By Category. 2011a; (March 8, 2011). Available at www.bt.cdc.gov/agent/agentlist-category.asp/ Accessed April28, 2013

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases. 2011b; 2011(July17). Available at www.cdc.gov/ncezid/ Accessed October31, 2013

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention CDC Estimates of Foodborne Illness in the United States. 2012. Available at www.cdc.gov/foodborneburden/ Accessed April26, 2013

- Cinquetti G, Banal F, Dupuy AL, Girault PY, et al. Three related cases of cutaneous anthrax in France: Clinical and laboratory aspects. Medicine (Baltimore) 2009; 88:371–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleaveland S, Laurenson MK, Taylor LH. Diseases of humans and their domestic mammals: Pathogen characteristics, host range and the risk of emergence. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2001; 356:991–999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman PG. Zoonotic diseases and their impact on the poor. Investing in Animal Health Research to Alleviate Poverty. Nairobi: International Livestock Research Institute 2002;1–29 [Google Scholar]

- Collins JD. Tuberculosis in cattle: Strategic planning for the future. Vet Microbiol 2006; 112:369–381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cvetnic Z, Katalinic-Jankovic V, Sostaric B, Spicic S, et al. Mycobacterium caprae in cattle and humans in Croatia. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2007; 11:652–658 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Amore M, Lisi S, Sisto M, Cucci L, Dow CT. Molecular identification of Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis in an Italian patient with Hashimoto's thyroiditis and Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome. J Med Microbiol 2010; 59:137–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies PDO. Tuberculosis in humans and animals: Are we a threat to each other? J R Soc Med 2006; 99:539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Kantor IN, Ambroggi M, Poggi S, Morcillo N, et al. Human Mycobacterium bovis infection in ten Latin American countries. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2008; 88:358–365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De la Rua-Domenech R. Human Mycobacterium bovis infection in the United Kingdom: Incidence, risks, control measures and review of the zoonotic aspects of bovine tuberculosis. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2006; 86:77–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Souza Trindade G, Drumond BP, Guedes MIMC, Leite JA, et al. Zoonotic vaccinia virus infection in Brazil: Clinical description and implications for health professionals. J Clin Microbiol 2007; 45:1370–1372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delpietro HA, Larghi OP, Russo RG. Virus isolation from saliva and salivary glands of cattle naturally infected with paralytic rabies. Prev Vet Med 2001; 48:223–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devriese LA, Hommez J. Epidemiology of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in dairy herds. Res Vet Sci 1975; 19:23–27 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doganay M, Aygen B. Diagnosis: Cutaneous anthrax. Clin Infect Dis 1997; 25:725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essbauer S, Pfeffer M, Meyer H. Zoonotic poxviruses. Vet Microbiol 2010; 140:229–236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Federal Bureau of Investigation Amerithrax or Anthrax Investigation. 2011. Available at www.fbi.gov/about-us/history/famous-cases/anthrax-amerithrax/amerithrax-investigation/ Accessed April26, 2013

- Fields BN, Knipe DM, Howley PM, Griffin DE. Fields' Virology, 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2001 [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations FAOSTAT. 2010. Data. Available at http://faostat.fao.org/site/339/default.aspx/ and http://faostat3.fao.org/home/index.html/ Accessed April26, 2013

- Fritsche A, Engel R, Buhl D, Zellweger JP. Mycobacterium bovis tuberculosis: From animal to man and back. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2004; 8:903–904 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gear JH, Thomson PD, Hopp M, Andronikou S, et al. Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever in South Africa. Report of a fatal case in the Transvaal. S Afr Med J 1982; 62:576–580 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]