Abstract

The regulation of centrosome number is lost in many tumors and the presence of extra centrosomes correlates with chromosomal instability. Recent work now reveals how extra centrosomes cause chromosome mis-segregation in tumor cells.

Centrosomes are pivotal organizers of the microtubule cytoskeleton and their duplication and inheritance is strictly controlled during the cell cycle in a manner that parallels genome duplication [1]. This control is lost in many cancer cells, making the presence of extra centrosomes a discernible feature of many tumors [2]. This defect has long been associated with aneuploidy in cancer and it is postulated that additional centrosomes induce chromosome mis-segregation, which then contributes to tumorigenesis [3–6]. However, the relationship between centrosome number and chromosome content has always been correlative, with no direct mechanism linking the presence of additional centrosomes to chromosomal instability (CIN). In a recent study, Ganem and colleagues [7] now break through this correlation to demonstrate that extra centrosomes induce CIN by exacerbating erroneous attachments of chromosomes to spindle microtubules.

To understand the fate of cancer cells with extra centrosomes, the authors used time-lapse video microscopy to follow single cells as they proceeded through division. This straightforward strategy revealed that most tumor cells efficiently cluster extra centrosomes together into two spindle poles, as previously shown [8,9]. The resulting bipolar division yields viable progeny that are competent for further rounds of division. The new work showed that the few cells that failed to cluster centrosomes underwent multipolar division (i.e. produced more than two daughter cells), as previously hypothesized [9]. However, progeny from these aberrant multipolar divisions were inviable; either never dividing again or succumbing in the subsequent abortive round of division [7]. In addition, the frequency of multipolar division in cancer cells that had extra centrosomes was ~10-fold lower than the chromosome mis-segregation rate directly measured by fluorescence in situ hybridization. Together, these data dispel the popular notion that extra centrosomes contribute to CIN and aneuploidy by inducing multipolar cell division [2,6]. Presumably, it is virtually impossible for a daughter cell from a multipolar division to inherit sufficient chromosomes for viability. These findings also fit with previous work showing that aneuploidy and chromosome mis-segregation can reduce cellular viability [10,11], and that massive changes in chromosome content are not tolerated [12]. These results continue a recent trend where careful single-cell analyses have led to dramatic insights into cancer cell growth [10,13].

Building on those results, the authors sought to understand the incontestable correlation between extra centrosomes and CIN. Centrosomes are the dominant site of microtubule organization during mitosis and they direct the focusing of microtubules at spindle poles. Bipolar spindles form in normal cells under the direction of two centrosomes, and it is well documented that cells with extra centrosomes form multipolar spindles during early mitosis [2] prior to spindle bipolarization through centrosome clustering [9].Ganem et al. [7] suspected that these transient multipolar states created by extra centrosomes during spindle morphogenesis would disturb the proper attachment of microtubules to chromosomes at kinetochores. Using high resolution fluorescence microscopy, they found that mitotic cells with multipolar spindles (either naturally occurring in cancer cells with extra centrosomes or experimentally induced in normal diploid cells by artificially increasing centrosome numbers) exhibit elevated frequencies of maloriented kinetochore–microtubule attachments [7]. Single kinetochores were attached to microtubules emanating from two or more centrosomes as opposed to only one, a condition known as merotely [14]. Merotelic attachments impair chromosome segregation by causing lagging chromosomes during anaphase [15] and they have been shown to be the primary mechanism of CIN in cancer cells [10,16]. Ganem et al. [7] found that these merotelic kinetochore–microtubule attachments persisted even after the resolution of the multipolar intermediate into a bipolar structure through centrosome clustering.

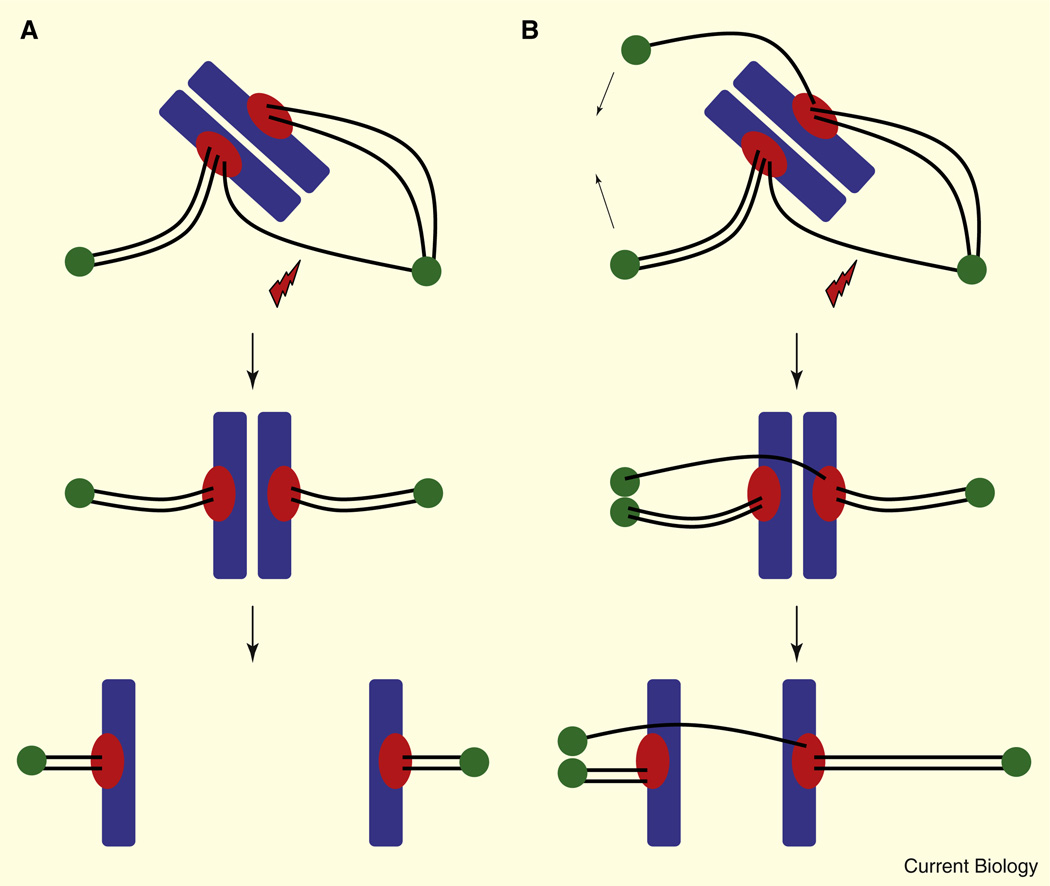

To bolster the link between extra centrosomes and CIN, the authors systematically examined the effect of increasing the number of centrosomes on chromosome segregation. First, they doubled the number of centrosomes in otherwise chromosomally stable diploid cells by inhibiting cytokinesis. Spindle formation in these newly formed tetraploid cells progressed through transient multipolar stages prior to clustering their extra centrosomes to make bipolar spindles just like cancer cells. This caused dramatic increases in the rates of lagging chromosomes and chromosome mis-segregation. The authors then selected tetraploid cells that had spontaneously lost their extra centrosomes and found that these cells reverted to rates of lagging chromosomes and chromosome mis-segregation comparable to normal diploid cells with two centrosomes. Furthermore, they selectively increased centrosome numbers by overexpressing Polo-like kinase 4 (PLK4), a key player in the cell-cycle-dependent control of centrosome number [17]. Overexpression of PLK4 generates extra centrosomes by producing additional centrioles that subsequently disengage from one another. Accordingly, PLK4 overexpression increased frequencies of lagging chromosomes 3-fold, but only after centrioles disengaged and generated extra centrosomes [7]. Combined, these data elegantly demonstrate that extra centrosomes induce CIN by generating transient multipolar spindles that elevate frequencies of kinetochore–microtubule attachment errors that lead to chromosome mis-segregation (Figure 1). Importantly, these results predict that eliminating extra centrosomes from long-term aneuploid cancer cells should suppress their inherent CIN, but this prediction remains to be tested; such testing would be important to further implicate the role of extra centrosomes as common inducers of CIN in cancer.

Figure 1. Extra centrosomes increase merotelic kinetochore–microtubule attachments.

(A) Normal diploid cells build bipolar spindles through the direction of two centrosomes (green). Spontaneously arising erroneous (merotelic) attachments of microtubules (black lines) to chromosomes (blue) at kinetochores (red) are corrected (red lightning blot) prior to anaphase onset to prevent chromosome mis-segregation. (B) Extra centrosomes in cancer cells induce multipolar spindles prior to bipolarization through centrosome clustering (arrows). These multipolar spindles increase the incidence of merotelic kinetochore–microtubule attachments that persist into anaphase and cause chromosome lagging and mis-segregation.

Merotelic attachments arise naturally during mitosis as a consequence of the stochastic nature of kinetochore–microtubule interactions, and in normal cells these attachment errors are corrected prior to anaphase onset to preserve genome stability [18]. This correction process relies on the release of mal-oriented microtubules from the kinetochores and is enabled by the dynamic kinetochore–microtubule interface [16]. The prevalence of merotelic attachments is therefore determined by the rate of their formation and the rate of their correction, and two observations presented by Ganem and colleagues [7] bear on how those rates impact CIN. First, they show that, although the incidence of merotelic attachments enhanced by multipolar spindles decreases as cells progress through mitosis and cluster centrosomes to form bipolar spindles, many attachment errors persist into anaphase, giving rise to lagging chromosomes [7]. This indicates that the machinery involved in correcting merotelic attachments is relatively inefficient and easily overwhelmed. Second, they show that frequencies of lagging chromosomes observed in normal diploid cells engineered to possess extra centrosomes does not reach levels seen in cancer cells with extra centrosomes, suggesting that cancer cells with CIN may have additional defects contributing to elevated rates of attachment errors. This also fits with other data showing that, when merotelic attachments are artificially elevated, normal cells consistently exhibit fewer lagging chromosomes than cancer cells with CIN [10,16], and that many cancer cell lines with a normal complement of two centrosomes still exhibit elevated rates of lagging chromosomes [7]. Thus, extra centrosomes contribute to CIN by elevating the rate of formation of merotelic attachments, but other mechanisms may be involved and it remains to be determined experimentally whether cancer cells are inherently deficient at correcting merotelic kinetochore–microtubule attachments. Irrespective of the causative defect, it has been shown that increasing the correction efficiency of merotelic attachments by promoting kinetochore–microtubule turnover reduces chromosome mis-segregation and suppresses CIN [16].

The pathway leading tumor cells from a diploid state to an aneuploid one has been a matter of debate and some hypothesize that tetraploidy is an essential intermediate step [19]. For tumor cells with near tetraploid karyotypes it has been proposed that failure of cytokinesis is a key step in their genesis and in tumor initiation [19]. In addition to duplicating the genome, failed cytokinesis also doubles the number of centrosomes and the work by Ganem et al. [7] shows how CIN would be an inevitable consequence for newly formed tetraploid cells. Furthermore, central to the mechanism for how extra centrosomes generate CIN is the clustering of extra centrosomes into bipolar spindles [9]. Centrosome clustering is beneficial to cancer cells because it prevents lethality caused by multipolar division as shown by the authors, but that benefit is balanced by the expense of elevated rates of single chromosome mis-segregation creating CIN. Nevertheless, the results point to a potentially new therapeutic strategy whereby chromosome mis-segregation rates in aneuploid tumor cells with CIN are intentionally elevated beyond tolerable levels [20]. The results presented by Ganem et al. [7] suggest that inhibition of centrosome clustering may be particularly effective for that strategy because it would force tumor cells with extra centrosomes into a suicidal multipolar division [9]. Most importantly, this strategy would spare normal cells with two centrosomes, opening the door for selective and targeted tumor therapy.

References

- 1.Bettencourt-Dias M, Glover DM. Centrosome biogenesis and function: centrosomics brings new understanding. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007;8:451–463. doi: 10.1038/nrm2180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nigg EA. Centrosome aberrations: Cause or consequence of cancer progression? Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2002;2:815–825. doi: 10.1038/nrc924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ghadimi BM, Sackett DL, Difilippantonio MJ, Schrock E, Neumann T, Jauho A, Auer G, Ried T. Centrosome amplification and instability occurs exclusively in aneuploid, but not in diploid colorectal cancer cell lines, and correlates with numerical chromosomal aberrations. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2000;27:183–190. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pihan GA, Purohit A, Wallace J, Malhotra R, Liotta L, Doxsey SJ. Centrosome defects can account for cellular and genetic changes that characterize prostate cancer progression. Cancer Res. 2001;61:2212–2219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Basto R, Brunk K, Vinadogrova T, Peel N, Franz A, Khodjakov A, Raff JW. Centrosome amplification can initiate tumorigenesis in flies. Cell. 2008;133:1032–1042. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.05.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.D’Assoro AB, Lingle WL, Salisbury JL. Centrosome amplification and the development of cancer. Oncogene. 2002;21:6146–6153. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ganem NJ, Godinho SA, Pellman D. A mechanism linking extra centrosomes to chromosomal instability. Nature. 2009 doi: 10.1038/nature08136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quintyne NJ, Reing JE, Hoffelder DR, Gollin SM, Saunders WS. Spindle multipolarity is prevented by centrosomal clustering. Science. 2005;307:127–129. doi: 10.1126/science.1104905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kwon M, Godinho SA, Chandhok NS, Ganem NJ, Azioune A, Thery M, Pellman D. Mechanisms to suppress multipolar divisions in cancer cells with extra centrosomes. Genes Dev. 2008;22:2189–2203. doi: 10.1101/gad.1700908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thompson SL, Compton DA. Examining the link between chromosomal instability and aneuploidy in human cells. J. Cell Biol. 2008;180:665–672. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200712029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williams BR, Prabhu VR, Hunter KE, Glazier CM, Whittaker CA, Housman DE, Amon A. Aneuploidy affects proliferation and spontaneous immortalization in mammalian cells. Science. 2008;322:703–709. doi: 10.1126/science.1160058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kops G, Foltz DR, Cleveland DW. Lethality to human cancer cells through massive chromosome loss by inhibition of the mitotic checkpoint. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:8699–8704. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401142101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gascoigne KE, Taylor SS. Cancer cells display intra- and interline variation profound following prolonged exposure to antimitotic drugs. Cancer Cell. 2008;14:111–122. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cimini D, Howell B, Maddox P, Khodjakov A, Degrassi F, Salmon ED. Merotelic kinetochore orientation is a major mechanism of aneuploidy in mitotic mammalian tissue cells. J. Cell Biol. 2001;153:517–527. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.3.517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cimini D, Fioravanti D, Salmon ED, Degrassi F. Merotelic kinetochore orientation versus chromosome mono-orientation in the origin of lagging chromosomes in human primary cells. J. Cell Sci. 2002;115:507–515. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.3.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bakhoum SF, Thompson SL, Manning AL, Compton DA. Genome stability is ensured by temporal control of kinetochore-microtubule dynamics. Nat. Cell Biol. 2009;11:27–35. doi: 10.1038/ncb1809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kleylein-Sohn J, Westendorf J, Le Clech M, Habedanck R, Stierhof YD, Nigg EA. Plk4-induced centriole biogenesis in human cells. Dev. Cell. 2007;13:190–202. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cimini D, Moree B, Canman JC, Salmon ED. Merotelic kinetochore orientation occurs frequently during early mitosis in mammalian tissue cells and error correction is achieved by two different mechanisms. J. Cell Sci. 2003;116:4213–4225. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fujiwara T, Bandi M, Nitta M, Ivanova EV, Bronson RT, Pellman D. Cytokinesis failure generating tetraploids promotes tumorigenesis in p53-null cells. Nature. 2005;437:1043–1047. doi: 10.1038/nature04217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lengauer C, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Genetic instabilities in human cancers. Nature. 1998;396:643–649. doi: 10.1038/25292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]