Abstract

Objective

Dentinal MMPs have been claimed to contribute to the auto-degradation of collagen fibrils within incompletely resin-infiltrated hybrid layers and their inhibition may, therefore, slow the degradation of hybrid layer. This study aimed to determine the contribution of a synthetic MMPs inhibitor (Galardin) to the proteolytic activity of dentinal MMPs and to the morphological and mechanical features of hybrid layers after aging.

Methods

Dentin powder obtained from human molars was treated with Galardin or chlorhexidine digluconate and zymographically analyzed. Microtensile bond strength was also evaluated in extracted human teeth. Exposed dentin was etched with 35% phosphoric acid and specimens were assigned to (1) pre-treatment with Galardin as additional primer for 30s; (2) no pre-treatment. A two-step etch-and-rinse adhesive (Adper Scotchbond 1XT, 3M ESPE) was then applied in accordance with manufacturer's instructions and resin composite build-ups were created. Specimens were immediately tested for their microtensile bond strength or stored in artificial saliva for 12 months prior to being tested. Data were evaluated by two-way ANOVA and Tukey's tests (〈=0.05). Additional specimens were prepared for interfacial nanoleakage analysis under light microscopy and TEM, quantified by two independent observers and statistically analyzed (|2 test, 〈=0.05).

Results

The inhibitory effect of Galardin on dentinal MMPs was confirmed by zymographic analysis, as complete inhibition of both MMP-2 and -9 was observed. The use of Galardin had no effect on immediate bond strength, while it significantly decreased bond degradation after 1 year (p<0.05). Interfacial nanoleakage expression after aging revealed reduced silver deposits in galardin-treated specimens compared to controls (p<0.05).

Conclusions

This study confirmed that the proteolytic activity of dentinal MMPs was inhibited by the use of Galardin in a therapeutic primer. Galardin also partially preserved the mechanical integrity of the hybrid layer created by a two-step etch-and-rinse adhesive after artificial aging.

Keywords: Galardin, dental bonding systems, hybrid layer, aging, dentin

Introduction

Formation of a perfect resin-infiltrated hybrid layer, composed of collagen fibrils embedded by methacrylate-based resins, has been thought as essential to provide durable and successful adhesion to human dentin. The breakdown of resin-bonded interfaces has been directly related with the loss of stability of the hydrophilic resin components that comprises the hybrid layers [1-3]. Nevertheless, the clinical implications of the integrity of dentin matrices within in vivo hybrid layers have been increasingly demonstrated as being fundamental for the loss of longevity of resin-bonded restorations [3-5].

The outstanding resistance of the collagenous dentin matrix against thermal and proteolytic disruption has been attributed to the high degree of intermolecular crosslinking and tight mechanical weave of this specialized connective tissue [6-8]. However, great attention to the potential proteolytic activity of dentin has been raised since complexed and active forms of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) were identified in either non-mineralized or mineralized compartments of human dentin matrices [9-15]. MMPs belong to a group of zinc- and calcium-dependent enzymes that have been shown to be able to cleave native collagenous tissues at neutral pH in the metabolism of all connective tissues [16,17].

Dentin matrix has shown to contain at least four MMPs: the stromelysin-1 (MMP-3) [15], the true collagenase (MMP-8) [14] and the gelatinases A and B, (MMP-2 and MMP-9 respectively) [9,13]. These host-derived proteases are thought to play an important role in numerous physiological and pathological processes occurring in dentin, including the degradation of collagen fibrils that are exposed by suboptimally infiltrated dental adhesive systems after acid etching [4,5,12,18].

Collagenolytic/gelatinolytic activity of human dentin matrices [12] has recently shown to be suppressed by a nonspecific protease inhibitor, chlorhexidine digluconate (CHX) [19], at two concentrations: 0.2% (2.2 mM) [20] and 2% (22 mM) [4,5,12,20] and this inhibition has reported to be beneficial in the preservation of the hybrid layer both in vivo [4,5,21] and in vitro [20,22].

Although the use of CHX as antiproteolytic primer for dentin matrix preservation has shown to be extremely convenient due to its commercial availability as mouthrinse agent (at 0.12 – 0.2%) and cavity disinfectant (at 2%), it is quite reasonable to speculate that specific MMP inhibitors, which normally exert inhibitory activity under extremely low concentrations, may be as or even more effective than CHX in increasing the durability of hybrid layers.

Galardin is a synthetic MMP inhibitor with potent activity against MMP-1, -2, -3 -8 and -9 [23,24] and its action was firstly reported in the 90's by Grobelny et al [23]. Galardin has a collagen-like backbone to facilitate binding to the active site of MMPs and a hydroxamate structure (R-CO-NH-OH, where R is an organic residue) which chelates the zinc ion located in the catalytic domain of MMPs [25]. Galardin, also known as GM6001 or Ilomastat, has been used to selectively inhibit MMP-2, -3, -8 and -9 [26,27] that have already been demonstrated to be present in human dentin matrix [9,13,14,15].

Thus, the aim of this study was to test the efficacy of galardin on the morphological and mechanical preservation of aged hybrid layers. It was hypothesized that: 1) the gelatinolytic activity of phosphoric-acid demineralized dentin is similarly inhibited by CHX and galardin; 2) galardin can preserve the morphological and mechanical integrity of aged hybrid layers.

Materials and Methods

Sixty recently extracted, non-carious human molars were collected after the patients' informed consent had been obtained under a protocol reviewed and approved by the Ethic Committee for Human Studies of the University of Trieste.

Zymographic analysis (Gelatinolytic activity of phosphoric-acid demineralized dentin)

Reagents were purchased from Sigma Chemical (St Louis, MO, USA) unless otherwise specified.

Twenty teeth were selected for this part of the study. Enamel and residual pulp tissue of these teeth were removed and dentin powder was obtained by pulverizing the liquid nitrogen-frozen dentin with a steel mortar/pestle (Reimiller, Reggio Emilia, Italy) in accordance with Mazzoni et al. [13]. Five 1-g aliquots of dentin powder were obtained and assigned to one of the following treatments: Group 1: untreated mineralized dentin powder; Group 2: dentin powder partially demineralized with 1% phosphoric acid for 10 min at 4°C; Group 3: dentin powder partially demineralized with 1% phosphoric acid for 10 min at 4°C then incubated with 0.2 mM galardin (water solution) for 30 min; Group 4 and 5: dentin powder partially demineralized with 1% phosphoric for 10 min then treated, respectively, with 2.2 mM (0.2%) and 22 mM (2%) CHX water solution for 30 min. All specimens were then rinsed with 1 mL of distilled water (5 times), then re-suspended for 24 h in 4 mL extraction buffer: 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 6, containing 5 mM CaCl2, 100 mM NaCl, 0.1% Triton X-100, 0.1% nonionic detergent P-40, 0.1 mM ZnCl2, 0.02% NaN3 and EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Germany). Specimens were centrifuged at 14000 rpm (Eppendorf, Minispin Plus, Hamburg, Germany,), supernatants were collected and protein content was precipitated with 25% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) at 4°C. TCA precipitates were re-solubilized in loading buffer pH 8.8 containing Trizma and 2% sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS) in water.

Total protein concentration of mineralized and partially demineralized dentin extracts was determined using the Bradford assay. Proteins were electrophorized under non-reducing conditions on SDS-polyacrylamide gels copolymerized with 2 g/L gelatin (porcine skin). Activation of gelatinase proforms was achieved with 2 mM p-aminophenylmercuric acetate (APMA) for 1 hr at 37°C and then the SDS-polyacrylamide gels were incubated for 24 hrs at 37°C in zymography buffer (CaCl2, NaCl and tris-HCl, pH 8.0). Gels were stained in 0.2% Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250 and destained in destaining buffer (50% methanol, 10% acetic acid, 40% water).

Control zymograms were incubated in the presence of 5 mM EDTA and 2 mM 1,10-phenanthroline to inhibit gelatinases.

Microtensile bond strength test

Twenty-eight of the selected teeth were used in this part of the study. Flat surfaces of middle/deep dentin were exposed with a slow speed diamond saw (Micromet, Bologna, Italy). Smear layer-covered dentin surfaces were etched with 35% phosphoric acid for 15 s (etching gel, 3M ESPE), rinsed and surfaces were blot dried according to the wet bonding technique. Specimens were randomly assigned to the following treatments (N=14). Groups 1: acid-etched dentin surfaces were treated with 0.2 mM galardin (water solution) for 30 s, blot-dried and bonded with SB1XT; Group 2: received no pre-treatment before SB1XT application (control). SB1XT was applied in accordance with manufacturer's instructions and light-cured. Resin composite build-ups were created with Filtek Z250 (3M ESPE, St. Paul, MN, USA).

Resin-dentin sticks with cross-sectional area of approximately 0.9 mm2 were obtained in accordance with the non-trimming technique [28]. Each stick was measured and recorded for bond strength calculation. Sticks were divided in two equal groups and either stored at 37°C for 24h (T0) or for 1yr (T1yr) in artificial saliva prepared in accordance with Pashley et al. [12], but without protease inhibitors. Sticks were stressed until failure with a simplified universal testing machine at a crosshead speed of 1 mm/min (Bisco Inc., Schaumburg, IL, USA). Failure modes were evaluated as described by Breschi et al. [20].

The number of prematurely debonded sticks per each tested group was also recorded, but not included in the statistical analysis since all premature failures occurred during the cutting procedure, which was performed at time zero and did not exceed 3% of the total number of tested specimens. As values were normally distributed (Kolmogorov-Smirnof test), data were analyzed with a two-way ANOVA (tested variables were: presence of galardin, time of storage) and Tukey's post hoc tests. To analyze the effect of galardin on fracture modes, mixed and dentin cohesive failures were combined when performing the statistical analysis. Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Test was used to analyze the differences in failure modes between T0 and T1yr for each group, and Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare the fracture modes between the groups within each time points. Statistical significance was set at 〈=0.05.

Nanoleakage evaluation

The remaining twelve teeth (N=3/group) were prepared and bonded as previously described for nanoleakage evaluation. Resin-bonded specimens were then vertically cut into 1-mm thick slabs to expose the bonded surfaces, which were further submitted to storage in artificial saliva at 37°C for two different times: T0 (24 hr) and T1yr (1 year). After storage (24hr or 1yr), the resin-bonded interfaces were immersed in 50 wt% ammoniacal AgNO3 solution according to the protocol described by Tay et al. [1], thoroughly rinsed in distilled water, and immersed in photodeveloping solution. The silver-impregnated specimens were fixed, dehydrated, embedded in epoxy resin (Epon 812; Fluka, Buchs, Switzerland), and processed for light microscopy (LM) in accordance with Saboia et al. [29].

Briefly, specimens were fixed on glass slides using cyanoacrylate glue, flattened with 600, 800, 1200, and 2400 grit SiC paper under running water (LS2; Remet) and stained with 0.5% acid fuchsine for 15 min, finally analyzed by light microscopy (Nikon E 800; Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). All interface images were obtained at a magnification of 100× and the amount of silver tracer precipitation along the interface (i.e., the degree of interfacial nanoleakage) was scored on a scale of 0 to 4 by two observers in accordance with Saboia et al. [29], i.e. interfacial nanoleakage was scored based on the percentage of the adhesive surface showing silver nitrate deposition: 0, no nanoleakage; 1, < 25% with nanoleakage, 2, 25 δ 50% with nanoleakage; 3, 50 δ 75% with nanoleakage; 4, > 75% with nanoleakage (Table 2). Intra-examiner reliability was assessed by the Kappa test (K=0.84). Statistical differences among score groups (i.e. number of specimens falling within each score category) were analysed using the |2-test (p<0.05).

Table 2.

Bond strengths of 0.04% Galardin (GL)-treated specimens bonded with Adper Scotchbond 1XT vs control that were tested immediately (T0) or after 1 year (T1yr) of aging in artificial saliva. Distribution of failure mode (in %) among tested groups in the different periods of analysis and nanoleakage expression at light microscopy are also reported. A: adhesive; CD: cohesive failure in dentin; CC: cohesive failure in resin composite; M: mixed failure, as described by Breschi et al., 2008b.

| Bonding strategy | Bond strength | Failure Mode (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | CD | CC | M | |||

| GL + SB1XT | immediate | 44.1±7.3a (7) [1/140] | 30A | 5B | 20A | 55C |

| 1yr | 32.4±6.6b (7) [4/144] | 26A | 7B | 18A | 49C | |

| SB1XT control | immediate | 41.4±5.9a (7) [3/152] | 20A | 7B | 28A | 45C |

| 1yr | 22.6±5.4c (7) [1/149] | 24A | 5B | 19A | 52C | |

Values are mean ± SD (number of teeth) in MPa [number of premature failed sticks/number of intact sticks tested]. Groups identified by different lower case letters are significantly different (p<0.05). Groups identified by the same uppercase letters are not significantly different (p>0.05).

Additional embedded specimens were processed for nanoleakage analysis under TEM in accordance with Suppa et al. [30] and examined under TEM (Philips CM-10, Eindhoven, The Netherlands) operating at 70 kV.

Results

Zymographic analysis

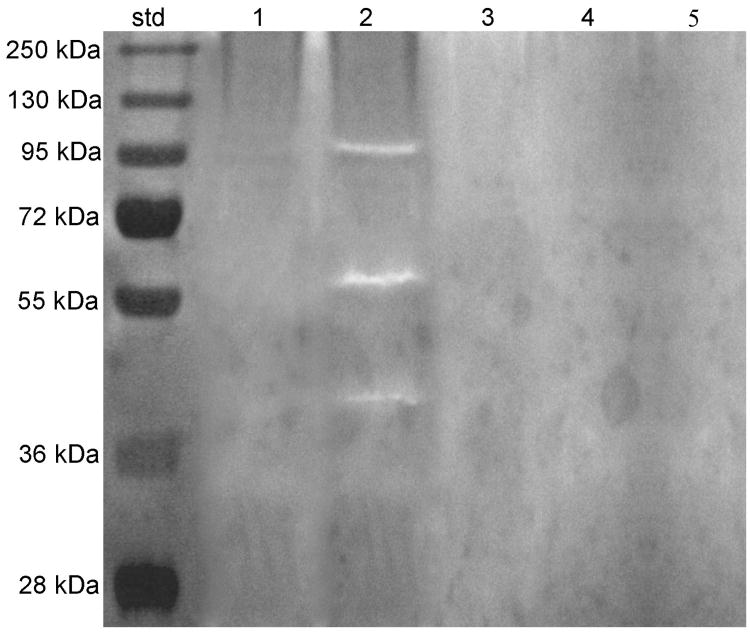

Mineralized dentin powder did not show any enzymatic activity (Group 1, Fig.1, Lane 1). Zymograms of 1% phosphoric acid demineralized dentin extracts (Group 2) showed multiple forms of gelatinolytic enzymes (Fig. 1, Lane 2), with the 66-kDa activity identified as MMP-2 active-form, and fainter bands of 92 kDa, as pro-MMP-9 along with truncated forms. Treatment with 0.2 mM galardin (Fig.1, Lane 3), 2.2 mM or 22mM CHX (Fig. 1, Lane 4 and 5) showed complete inhibition of both MMP-2 and -9 activities.

Figure 1.

Gelatin zymogram of MMPs from dentin extracts after sonication, TCA precipitation, resuspension and activation with 2mM APMA for 1 hour. Molecular masses, expressed in kDa, are reported in Std lane. Lane 1: Absence of any gelatinolytic activities in proteins extracted from mineralized dentin powder; Lane 2: identification of MMP-2 and -9 isoforms in phosphoric acid-treated dentin; Lane 3: Phosphoric acid-demineralized dentin incubated with Galardin revealed inhibition of all MMPs isoforms; Lanes 4 and 5: incubation with 0.2 or 2% CHX respectively, produced complete inhibition of all forms of MMP-2 and -9 activity in phosphoric acid demineralized dentin.

Control zymograms incubated with 5 mM EDTA and 2 mM 1,10-phenanthroline showed no enzymatic activity (data not shown).

Microtensile bond strength and fracture mode analyses

Mean bond strength obtained at T0 and T1yr and failure mode distributions are summarized in Table 2. At T0, there were no differences between the bond strength of galardin-treated specimens vs control (galardin+SB1XT = 44.1±7.3 MPa; SB1XT control = 41.4±5.9 MPa; p>0.05). A significant decrease in bond strengths was found after 1 year of in vitro storage (T0>T1yr; p<0.05), however while bond strength decreased approximately 27% in the galardin-treated group, the decrease of bond strength was up to 45% in SB1XT-control group (galardin + SB1XT = 32.4±6.6; SB1XT control = 22.6±5.4 MPa; p<0.05). Fracture mode analysis did not demonstrate any statistically significant differences between the groups or within the groups at either time points (Table 2).

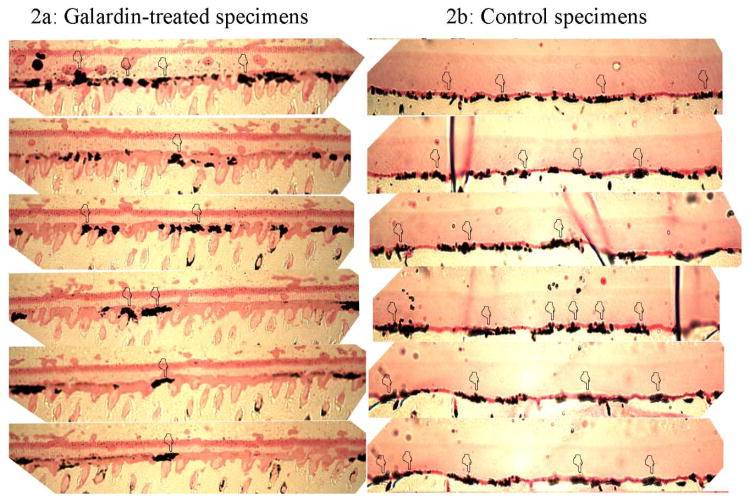

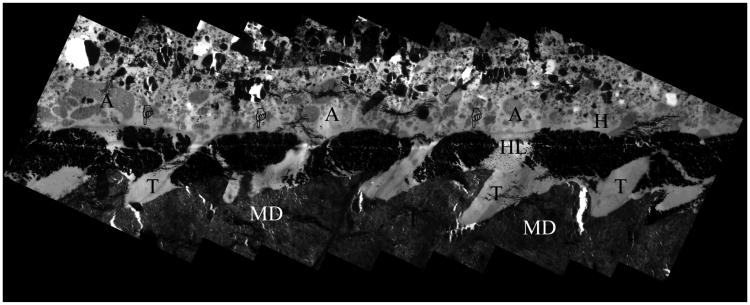

Interfacial nanoleakage analysis

Data regarding the extent of silver nitrate deposition along the bonded interface performed under LM are shown in Table 2. Although 1 yr of in vitro aging in artificial saliva caused increase in interfacial nanoleakage expression (p<0.05), the galardin-treated group showed minor nanoleakage expression compared to the untreated control specimens (Fig. 2; Table 2; p<0.05). TEM correlative analysis of the interfacial nanoleakage expression produced similar results (Fig. 3,4).

Figure 2.

Light microscopy images of bonded interfaces created by Adper Scotchbond 1XT stored for 1 yr in artificial saliva at 37°C. The semi-thin sections reveal that the use of Galardin as therapeutic primer significantly reduced the amount of silver nitrate at the interface (Fig. 2a; pointers), compared to extensive nanoleakage formation that can be seen along the hybrid layer on control specimens (Fig. 2b; pointers).

Figure 3.

TEM image obtained combining several micrographs of a representative specimen treated with Galardin for 30s, then bonded with SB1XT and stored for 1 yr in artificial saliva at 37°C. The adhesive (A) interface revealed few scattered clusters (pointers) of silver nanoleakage within the hybrid layers (HL). MD = mineralized dentin; T = dentinal tubules; A = filled adhesive. Bar = 2 ⌠ m.

Figure 4.

TEM image obtained combining several micrographs of a representative control specimen bonded with SB1XT and stored for 1 yr in artificial saliva at 37°C. The adhesive interface reveals extensive interfacial silver nanoleakage due to large clusters of silver deposits (pointers) within the collagen fibrils of the hybrid layer (HL). Abbreviations are same as in Fig. 2. Bar = 2 ⌠m.

Discussion

Complete inhibition of the gelatinolytic activity of phosphoric-acid demineralized dentin was verified in zymograms after treatment of dentin powder with 0.2 mM galardin, 2.2 mM (0.2%) and 22 mM (2%) CHX. No difference in the enzymatic inhibition of demineralized dentin was observed when galardin- and CHX-treated dentin specimens were conjunctly assayed, which supports the acceptance of the first hypothesis of this study. Galardin-treated dentin showed a 27% reduction in bond strength after 1 yr of aging that was significantly less (p<0.05) than the 45% reduction in bond strength seen in untreated controls. Galardin-treatment also substantially reduced the nanoleakage of resin-bonded interfaces at 1 yr as well. Accordingly, these results support the acceptance of the second testing hypothesis.

Nanoleakage involves the diffusion of ammoniacal silver nitrate into water-filled voids or channels in hybrid layers. As the uninhibited endogenous MMP activity resin-infiltrated dentin matrices expresses itself over 1 year of storage, insoluble collagen fibrils are slowly broken down to gelatin. Gelatin peptides are then broken down by gelatinases to smaller peptides and amino acids that elute from the degradating hybrid layers. Their mass is replaced by water. Thus, higher silver uptake equates with the increase in water uptake that follows loss of collagen and resin stability. The increase in nanoleakage is consistent with the reported degradations of collagen fibrils in hybrid layers [4,5,21,31]. The increased presence of nanoleakage in the adhesive layer after 1 year of storage has previously been reported by Tay et al. [32] and by Reis et al. [33].

The present study supports the concept that the poor stability of hybrid layers is partly related to the activity of endogenous dentinal MMPs [9,12,14,15,18,34]. The fact that CHX has shown to preserve in vivo and in vitro hybrid layers is a breakthrough, but it is an indirect demonstration of the contribution of MMPs embedded within the dentin matrix for resin-dentin bonds degradation. In other words, CHX being a broad-spectrum antimicrobial agent and also a non-specific MMP-inhibitor, it might have enhanced the lifetime of tested hybrid layers not solely by controlling the activity of MMPs, but also by inhibiting other dentin matrix enzymes or even by a detergent-like effect than enhanced the impregnation of resin monomers into demineralized dentin. However, since galardin (a specific synthetic MMP-inhibitor) currently demonstrated a similar ability to slow the breakdown of resin-bonded interfaces, as previously showed when using CHX [4,5,20,21], it is now more evident that specific inhibition of dentinal MMPs may be important to increase the life span of adhesive restorations.

Some collagenase/gelatinase inhibitors act by non-specific chelation of cations such as zinc and calcium that are required to maintain the enzymatic function of MMPs. These inhibitors include EDTA [35], tetracyclines [36] and CHX [19]. Nevertheless, advantage can be taken from an agent that specifically inhibits a protein-target, as its inhibitory function is effectively reached at very low concentrations. Generally, the effective concentration of specific MMP-inhibitors is in the nanomolar range. For instance, galardin was previously shown to efficiently inhibit some MMPs with concentrations as low as 0.4 nM for MMP-2 (gelatinase A), 0.5 nM for MMP-3 (stromelysin-1), 3.7 nM for MMP-8 (neutrophil collagenase) and 0.1 nM for MMP-9 (gelatinase B) [26,27].

Previous MMP inhibition studies done with Galardin were done using soluble enzymes. These studies demonstrated that nanomolar concentrations of Galardin were effective at inhibiting MMPs [26,27]. In adhesive dentistry, acid etching both uncovers and activates MMPs that remain bound to collagen. The concentration of Galardin required to completely inhibit the endogenous bound MMPs in dentin may be much higher than that of unbound soluble MMPs.

The similarity between the inhibitory function of 0.2 mM galardin compared with that provided by 2.2 mM (0.2%) and 22 mM (2%) CHX in the zymographic analysis strengthens the concept that the use of specific permits much lower concentrations for enzymatic inhibition. It is notable that by using a concentration approximately 10 to 100 times lower, galardin inhibited the proteolytic activity of demineralized dentin as efficiently as performed by CHX. We speculate that even lower concentrations of other specific MMP inhibitors could lead to complete inhibition of hybrid layer degradation. While galardin is an effective inhibitor of pure soluble MMPs even at lower concentrations than the currently tested one [26,27], we decided to use a galardin saturated solution (0.2 mM if water is used as solvent) to challenge simultaneously its effect on the proteolytic activity of dentin and its possible interference on the formation of the hybrid layer. Since the results demonstrated that 0.2 mM galardin did not affect the immediate bond strength and nanoleakage, while it significantly reduced decreases bond strength over time (1yr-result), this study supports the hypothesis that galardin does not interfere with the hybrid layer formation when a two-step etch-and-rinse adhesive is used.

It is noticeable that galardin-treatment slowed the decline of bond strength and reduced the amount of nanoleakage, but it did not completely block these phenomena (Table 2; Figure 2,3). The observed decline in the bond strength of galardin-treated specimens can be related with the loss of integrity of resinous components within hybrid layers due to polymer swelling and resin leaching that occurs after water/oral fluid sorption [37,38]. The leaching effect may be especially strong in in vitro microtensile testing, as comparable decrease in bond strenght was observed with CHX in vitro [22], while the loss of bond strength was completely inhibited in vivo [5]. In any case, to maximize the stability of such bonded interfaces, efforts should be made to combine the use of antiproteolytic agents with the use relatively hydrophobic monomers to infiltrate the dentin matrix.

The results of the current study indicate that galardin as an inhibitor of dentinal MMPs may be clinically relevant way to improve hybrid layer long-term stability. Galardin may be as stable as CHX in hybrid layers. Perhaps galardin should be delivered as an ethanol solution at higher concentrations. In ophthalmology, corneal ulcerations induced by herpetic or alkaline solutions activate corneal MMPs and continue to grow unless inhibited. The use of prolonged topical treatment (30 days) of corneal ulcerations by 1 mM galardin caused no toxic effects [39]. Our use of topical galardin to stabilize the collagen fibrils of hybrid layers is an analogues example of how MMP-inhibitors used for many years in medicine, can be utilized in dentistry.

Despite the fact that the role of endogenous enzymes in the degradation of the hybrid layer is not fully elucidated, this study clarifies the importance of their specific inhibition to preserve the hybrid layer.

Previously published work emphasized the degradation of dental resins as being responsible for reductions in bond strength over time. However, the in vivo study by Carrilho et al. [5] showed that 2% CHX prevented decreases in bond strength for 14 months and prevented degradation of collagen fibrils in hybrid layers. That study clearly identified that preservation of collagen, not resin preserved bond strength for SB1XT. The current study further supports the Carrilho et al. [5] report by showing that specific MMP-inhibitors can also preserve bond strength over time. These results indicate that a paradigm shift has occurred in adhesive dentistry. That is, that preservation of resin-bonded interfaces requires prevention of degradation of collagen fibrils in hybrid layers.

Table 1. Composition of Adper Scotchbond 1 XT and mode of application.

| Adhesive | Composition | Mode of application |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Adper Scotchbond 1XT | Etching: | etching 15 s water rinsing 30 s dentine blot drying adhesive application |

| 35% phosphoric acid | ||

Primer/Bond:

| ||

Table 3.

Distribution of nanoleakage in Galardin (GL-) treated specimen and controls 24 hours and 1 year after composite adhesion as described in Saboia et al., 2008. Numbers in Table indicate the percentage of samples with respective nanoleakage (from 0 to >75% of adhesive joint) as observed with 100x magnification in light microscope. The respective bars demonstrate significantly smaller percentage (12%) of marked (>50%) nanoleakage in GL-treated samples compared to controls (59%) after 1 year storage in vitro in artificial saliva.

|

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Mr. Aurelio Valmori for photographical assistance, Dr. Francesca Vita and Mr. Claudio Gamboz for extensive technical assistance in ultra-microtomy. The study was partially supported by grants from “Università di Trieste-Finanziamento Ricerca d'Ateneo”, MIUR, Italy and FAPESP #07/54618-4 (P.I. Marcela Carrilho), Brazil and by grant R01 DE015306-06 from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR) to DHP (PI).

References

- 1.Tay FR, Pashley DH, Suh BI, Carvalho RM, Itthagarun A. Single-step adhesives are permeable membranes. J Dent. 2002;30:371–382. doi: 10.1016/s0300-5712(02)00064-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Munck J, Van Landuyt K, Peumans M, Poitevin A, Lambrechts P, Braem M, Van Meerbeek B. A critical review of the durability of adhesion to tooth tissue: methods and results. J Dent Res. 2005;84:118–132. doi: 10.1177/154405910508400204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Breschi L, Mazzoni A, Ruggeri A, Cadenaro M, Di Lenarda R, De Stefano Dorigo E. Dental adhesion review: aging and stability of the bonded interface. Dent Mater. 2008;24:90–101. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2007.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hebling J, Pashley DH, Tjäderhane L, Tay FR. Chlorhexidine arrests subclinical breakdown of dentin hybrid layers in vivo. J Dent Res. 2005;84:741–746. doi: 10.1177/154405910508400811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carrilho MRO, Geraldeli S, Tay FR, de Goes MF, Carvalho RM, Tjäderhane L, Reis AF, Hebling J, Mazzoni A, Breschi L, Pashley DH. In Vivo Preservation of Hybrid Layer by Chlorhexidine. J Dent Res. 2007;68:529–533. doi: 10.1177/154405910708600608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schlueter RJ, Veis A. The macromolecular organization of dentine matrix collagen. II. Periodate degradation and carbohydrate cross-linking. Biochemistry. 1964;3:1657–65. doi: 10.1021/bi00899a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Armstrong SR, Jessop JL, Winn E, Tay FR, Pashley DH. Denaturation temperatures of dentin matrices I. Effect of demineralization and dehydration. J Endod. 2006;32:638–651. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2005.10.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Armstrong SR, Jessop JL, Winn E, Tay FR, Pashley DH. Effects of polar solvents and adhesive resin on the denaturation temperatures of demineralised dentine matrices. J Dent. 2008;36:8–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martin-De Las Heras S, Valenzuela A, Overall CM. The matrix metalloproteinase gelatinase A in human dentine. Arch Oral Biol. 2000;45:757–765. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9969(00)00052-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tjäderhane L, Palosaari H, Wahlgren J, Larmas M, Sorsa T, Salo T. Human odontoblast culture method: the expression of collagen and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) Adv Dent Res. 2001;15:55–58. doi: 10.1177/08959374010150011401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Palosaari H, Pennington CJ, Larmas M, Edwards DR, Tjäderhane L, Salo T. Expression profile of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and tissue inhibitors of MMPs in mature human odontoblasts and pulp tissue. Eur J Oral Sci. 2003;111:117–127. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0722.2003.00026.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pashley DH, Tay FR, Yiu CKY, Hashimoto M, Breschi L, Carvalho R, Ito S. Collagen degradation by host-derived enzymes during aging. J Dent Res. 2004;83:216–221. doi: 10.1177/154405910408300306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mazzoni A, Mannello F, Tay FR, Tonti GA, Papa S, Mazzotti G, Di Lenarda R, Pashley DH, Breschi L. Zymographic analysis and characterization of MMP-2 and -9 isoforms in human sound dentin. J Dent Res. 2007;86:436–440. doi: 10.1177/154405910708600509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sulkala M, Tervahartiala T, Sorsa T, Larmas M, Salo T, Tjäderhane L. Matrix metalloproteinase-8 (MMP-8) is the major collagenase in human dentin. Arch Oral Biol. 2007;52:121–127. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2006.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boukpessi T, Menashi S, Camoin L, Tencate JM, Goldberg M, Chaussain-Miller C. The effect of stromelysin-1 (MMP-3) on non-collagenous extracellular matrix proteins of demineralized dentin and the adhesive properties of restorative resins. Biomaterials. 2008;29:4367–4373. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Birkedal-Hansen H, Moore WG, Bodden MK, Windsor LJ, Birkedal-Hansen B, DeCarlo A, Engler JA. Matrix metalloproteinases: a review. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1993;4:197–250. doi: 10.1177/10454411930040020401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nagase H, Woessner JF., Jr Matrix metalloproteinases. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:21491–21494. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.31.21491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mazzoni A, Pashley DH, Nishitani Y, Breschi L, Mannello F, Tjäderhane L, Toledano M, Pashley EL, Tay FR. Reactivation of inactivated endogenous proteolytic activities in phosphoric acid-etched dentine by etch-and-rinse adhesives. Biomaterials. 2006;27:4470–4476. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gendron R, Greiner D, Sorsa T, Maryrand D. Inhibition of the activities of matrix metalloproteinases 2, 8 and 9 by chlorexidine. Clin and Diagn Lab Immunol. 1999;6:437–439. doi: 10.1128/cdli.6.3.437-439.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Breschi L, Cammelli F, Visintini E, Mazzoni A, Vita F, Carrilho M, Cadenaro M, Foulger S, Tay FR, Mazzotti G, Di Lenarda R, Pashley D. Influence of chlorhexidine concentration on the durability of etch-and-rinse dentin bonds: a 12-month in vitro study. J Adhes Dent. 2009;11:191–198. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brackett WW, Tay FR, Brackett MG, Dib A, Sword RJ, Pashley DH. The effect of chlorhexidine on dentin hybrid layers in vivo. Oper Dent. 2007;32:107–111. doi: 10.2341/06-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carrilho MR, Carvalho RM, de Goes MF, di Hipólito V, Geraldeli S, Tay FR, Pashley DH, Tjäderhane L. Chlorhexidine preserves dentin bond in vitro. J Dent Res. 2007;86:90–94. doi: 10.1177/154405910708600115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grobelny D, Poncz L, Galardy RE. Inhibition of human skin fibroblast collagenase, thermolysin, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa elastase by peptide hydroxamic acids. Biochemistry. 1992;31:7152–7154. doi: 10.1021/bi00146a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hao JL, Nagano T, Nakamura M, Kumagai N, Mishima H, Nishida T. Galardin inhibits collagen degradation by rabbit keratocytes by inhibiting the activation of pro-matrix metalloproteinases. Exp Eye Res. 1999;68:565–572. doi: 10.1006/exer.1998.0637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Augé F, Hornebeck W, Decarme M, Laronze JY. Improved gelatinase a selectivity by novel zinc binding groups containing galardin derivatives. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2003;13:1783–1786. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(03)00214-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Galardy RE, Cassabonne ME, Giese C, Gilbert JH, Lapierre F, Lopez H, Schaefer ME, Stack R, Sullivan M, Summers B, Tressler R, Tyrrell D, Wee J, Allen SD, Castello JJ, Barletta JP, Schultz GS, Fernandez LA, Fisher S, Cui TY, Foellmer HG, Grobelny D, Holleran WM. Low molecular weight inhibitors in corneal ulceration. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1994;732:315–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1994.tb24746.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Galardy RE, Grobelny D, Foellmer HG, Fernandez LA. Inhibition of angiogenesis by the matrix metalloprotease inhibitor N-[2R-2-(hydroxamidocarbonymethyl)-4-methylpentanoyl)]-L-tryptophan methylamide. Cancer Res. 1994;54:4715–4718. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shono Y, Ogawa T, Terashita M, Carvalho RM, Pashley EL, Pashley DH. Regional measurement of resin-dentin bonding as an array. J Dent Res. 1999;78:699–705. doi: 10.1177/00220345990780021001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saboia VPA, Nato F, Mazzoni A, Orsini G, Putignano A, Giannini M, Breschi L. Adhesion of a two-step etch-and-rinse adhesive on collagen-depleted dentin. J Adhes Dent. 2008;10:419–422. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Suppa P, Breschi L, Ruggeri A, Mazzotti G, Prati C, Chersoni S, Di Lenarda R, Pashley DH, Tay FR. Nanoleakage within the hybrid layer: a correlative FEISEM/TEM investigation. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2005;73:7–14. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.30217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brackett MG, Tay FR, Brackett WW, Dib A, Dipp FA, Mai S, Pashley DH. In vivo chlorhexidine stabilization of hybrid layers of an acetone-based dental adhesive. Oper Dent. 2009;34:381–385. doi: 10.2341/08-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tay FR, Hashimoto M, Pashley DH, Peters MC, Lai SC, Yiu CK, Cheong C. Aging affects two modes of nanoleakage expression in bonded dentin. J Dent Res. 2003;82:537–541. doi: 10.1177/154405910308200710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reis AF, Arrais CA, Novaes PD, Carvalho RM, De Goes MF, Giannini M. Ultramorphological analysis of resin-dentin interfaces produced with water-based single-step and two-step adhesives: Nanoleakage expression. J Biomed Mater Res Part B: Appl Biomater. 2004;71B:90–98. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.30076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nishitani Y, Yoshiyama M, Wadgaonkar B, Breschi L, Mannello F, Mazzoni A, Carvalho RM, Tjäderhane L, Tay FR, Pashley DH. Activation of gelatinolytic/collagenolytic activity in dentin by self-etching adhesives. Eur J Oral Sci. 2006;114:160–166. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2006.00342.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.François J. The Seventh Frederick H. Verhoeff Lecture. Collagenase and collagenase inhibitors. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1977;75:285–315. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Golub LM, Lee HM, Lehrer G, Nemiroff A, McNamara TF, Kaplan R, Ramamurthy NS. Minocycline reduces gingival collagenolytic activity during diabetes. Preliminary observations and a proposed new mechanism of action. J Periodontal Res. 1983;18:516–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1983.tb00388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hashimoto M, Tay FR, Ohno H, Sano H, Kaga M, Yiu C, Kumagai H, Kudou Y, Kubota M, Oguchi H. SEM and TEM analysis of water degradation of human dentinal collagen. J Biomed Mater Res. 2003;66B:287–298. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.10560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.De Munck J, Van Meerbeek B, Yoshida Y, Inoue S, Vargas M, Suzuki K, Lambrechts P, Vanherle G. Four-year water degradation of total-etch adhesives bonded to dentin. J Dent Res. 2003;82:136–140. doi: 10.1177/154405910308200212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schultz GS, Strelow S, Stern GA, Chegini N, Grant MB, Galardy RE, Grobelny D, Rowsey JJ, Stonecipher K, Parmley V, Khaw PT. Treatment of alkali-injured rabbit corneas with a synthetic inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinases. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1992;33:3325–3331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]