Abstract

Objective

This study evaluated follow-up outcomes associated with cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for childhood anxiety by comparing successfully and unsuccessfully treated participants 6.72 to 19.17 years after treatment.

Method

Participants were a sample of 66 youth (ages 7 to 14 at time of treatment, ages 18 to 32 at present follow-up) who had been diagnosed with an anxiety disorder and randomized to treatment in a randomized clinical trial on average 16.24 (SD = 3.56, Range = 6.72–19.17) years prior. The present follow-up included self-report measures and a diagnostic interview to assess anxiety, depression, and substance misuse.

Results

Compared to those who responded successfully to CBT for an anxiety disorder in childhood, those who were less responsive had higher rates of Panic Disorder, Alcohol Dependence, and Drug Abuse in adulthood. Relative to a normative comparison group, those who were less responsive to CBT in childhood had higher rates of several anxiety disorders and substance misuse problems in adulthood. Participants remained at particularly increased risk, relative to the normative group, for Generalized Anxiety Disorder and Nicotine Dependence regardless of initial treatment outcome.

Conclusions

The present study is the first to assess the long-term follow-up effects of CBT treatment for an anxiety disorder in youth on anxiety, depression, and substance abuse through the period of young adulthood when these disorders are often seen. Results support the presence of important long-term benefits of successful early CBT for anxiety.

Keywords: Cognitive-behavioral therapy, anxiety, child anxiety, treatment outcome, long-term follow-up

Anxiety disorders are common in youth (e.g., Bernstein & Borchardt, 1991) and adults, based on 12-month prevalence estimates from the general population (Kessler, Chui, Demler, & Walters, 2005) and across the lifespan (28.8%; Kessler, Berglund, Demler, Jin, & Walters, 2005). Approximately 10 to 20% of children in the general population and primary care settings report distressing levels of anxiety (Chavira, Stein, Bailey, & Stein, 2004; Costello, Mustillo, Keeler, & Angold, 2004). Research suggests that most anxiety disorders do not abate over time (e.g., Pine, Cohen, Gurley, Brook, & Ma, 1998). Indeed, retrospective reports demonstrate that adults with anxiety disorders report having experienced disturbing anxiety as children (e.g., Ost, 1987; Sheehan, Sheehan, & Minichiello, 1981) and older youth report higher levels of anxiety and depression compared to younger children, suggesting untreated anxiety symptoms worsen over time.

Anxiety disorders in youth have important long-term implications in terms of their association with later depressive disorders (Alpert, Maddocks, Rosenbaum, & Fava, 1994; Angold, Costello, & Erkanli, 1999; Biederman, Faraone, Mick, & Lelon, 1995; Strauss, Lease, Last, & Francis, 1988), suicidal attempts and ideation (Brent et al., 1986; Rudd, Joiner, & Rumzek, 2004), and substance use (Costello, Mustillo, Erkanli, Keeler, & Angold, 2003; Lopez, Turner, & Saavadra, 2005). As age increases, the presence of an anxiety disorder has an associated increase in the likelihood of a depressive disorder (Beesdo et al., 2007, Pine et al., 1998), and anxiety disorders typically precede the onset of substance use disorders (SUDs; Merikangas et al., 1998). Given the high lifetime co-occurrence of anxiety and SUDs (35% to 45%; Kessler et al., 1996) and the deleterious outcomes associated with substance dependence (Toumbourou et al., 2007), this primacy warrants further investigation. Indeed, there is evidence that effective short-term treatment for adolescent depression is associated with reduced SUDs (Curry et al., 2012). Initial data suggested that CBT for child anxiety may allay later substance use (e.g., Kendall, Safford, Flannery-Schroeder, & Webb, 2004), but that evaluation was undertaken before participants reached the age of greatest risk for associated disorders.

Several studies have examined CBT for childhood anxiety and literature reviews support its utility: CBT can be considered an efficacious treatment (based on the criteria proposed by Chambless & Hollon, 1998; see Hollon & Beck, 2013; Kazdin & Weisz, 1998; Ollendick & King, 2012; Silverman, Pina, & Viswesvaran, 2008). Several randomized clinical trials (RCTs) reported the efficacy of one version of CBT for anxious youth, the Coping Cat program (Kendall & Hedtke, 2006), when compared to alternate psychological treatments (e.g., Kendall, Hudson, Gosch, Flannery-Schroeder, & Suveg, 2008) and to medications and pill placebo (e.g., Walkup et al., 2008).

Although multiple research groups have advanced the treatment of anxiety disorders in children (see also Barrett, Dadds, & Rapee, 1996; Beidel et al., 2007; Silverman et al., 2008), limited evidence exists with respect to sequelae at the time in adulthood when such disorders are likely to emerge. Several one-year follow-ups have been conducted (e.g., Kendall et al., 1997; Kolko, Loar, & Sturnick, 1990), as well as a 3-year (Beidel, Turner, Young, & Paulson, 2005), 5-year (Beidel, Turner, & Young, 2006), 6-year (Barrett, Duffy, Dadds, & Rapee, 2001) and 7.4-year follow-ups (Kendall et al., 2004). Longer follow-ups are uncommon and those that are available lack appropriate methodological rigor (e.g., do not follow a RCT). A review by Nevo and Manassis (2009) highlighted the dearth of long-term outcome studies of anxious youth and the lack of evidence for the role early anxiety treatment might play in healthy development into adulthood (see also Hirshfeld-Becker, Micco, Simoes, & Henin, 2008).

The present study evaluated outcomes associated with treatment for childhood anxiety by comparing (a) successfully treated and (b) unsuccessfully treated participants a mean of 16.24 years after the completion of treatment. The primary aim examined whether participants treated successfully during childhood differ from those for whom treatment was less successful on diagnoses of (a) adult anxiety, (b) depression, and (c) SUDs in young adulthood. A second aim examined whether the two treatment outcome groups differed from the general population on diagnoses of anxiety, depression, and SUDs in early adulthood. It was hypothesized that effective treatment for an anxiety disorder in childhood would reduce the occurrences of anxiety and related disorders in young adulthood. Further, it was hypothesized that successfully treated participants would be no more likely to meet criteria for an anxiety, mood, or SUD diagnosis than individuals in the community, whereas unsuccessfully treated participants would be more likely to meet criteria for a diagnosis than community individuals.

Method

All participants received treatment at the Child and Adolescent Anxiety Disorders Clinic (CAADC), Temple University. One sample came from a RCT reported in 1997 (Kendall et al.); others came from a RCT reported in 2008 (Kendall et al.). Both RCTs had participants randomized to treatment condition and to therapist. Treatment outcome was defined as the principal disorder at pretreatment no longer present at posttreatment.

Participants

Participants from Kendall et al. (1997)

The participants were children, aged 9–13 years at the time of intake, referred from multiple community sources, and diagnosed with a DSM principal anxiety disorder. All received CBT, though the study design required that 34 children be assigned to a wait-list. Wait-listed children were randomized to a therapist and given CBT if they continued to meet criteria for an anxiety disorder. For the present study, we attempted to contact all participants who were in the intent-to-treat sample (118). No additional exclusion criteria were used1. See Kendall et al. (1997) for a description of participant demographics at the time of initial presentation and treatment outcomes.

Participants from Kendall et al. (2008)

Additional participants were randomized to the same CBT (individual CBT; Kendall et al., 2008) as provided in Kendall et al. (1997). Participants were children, aged 7–14 years at intake, also referred from multiple community sources, and diagnosed with a DSM principal anxiety disorder. Of 161 children, 55 were randomized to individual CBT. For the present study, all participants randomized to the individual CBT condition of the RCT and ≥ 18 years of age at the time of the present follow-up were sought, resulting in a possible 32 participants. No additional exclusion criteria were used2. See Kendall et al. (2008) for initial participant demographics and outcomes.

Participant Demographics for the Present Follow-Up Study

Participants for the present study were a mean age of 27.23 (SD = 3.54) and completed treatment for anxiety in childhood a mean 16.24 (SD = 3.56, Range = 6.72–19.17) years prior to their present participation. Participants were 51.5% female and predominantly Caucasian (84.8%). The majority was employed (69.7%) and household incomes were variable. Most participants were college educated (M years of education = 15.3, SD = 2.20) and over half had never been married (56.1%). Pretreatment anxiety diagnoses were as follows: 56.1% had a principal diagnosis of Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD)/Overanxious Disorder of childhood (OAD), 27.3% Social Phobia (SP)/Avoidant Disorder (AV), and 16.7% Separation Anxiety Disorder (SAD). At posttreatment, 60.6% no longer met diagnostic criteria for their principal pretreatment diagnosis. See Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic Data: Frequency Data

| Variable | Overall Sample (N=66) | RCT-2 (n=54) | RCT-3 (n=12) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

|

|

|||

| Sex | |||

| Male | 32 (48.5%) | 25 (46.3%) | 7 (58.3%) |

| Female | 34 (51.5%) | 29 (53.7%) | 5 (41.7%) |

| Race | |||

| Caucasian | 56 (84.8%) | 45 (83.3%) | 11 (91.7%) |

| African American | 5 (7.6%) | 4 (7.4%) | 1 (8.3%) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 2 (3.0%) | 2 (3.7%) | 0 |

| Other/Biracial/Multiracial | 3 (4.5%) | 3 (5.6%) | 0 |

| Employment Status | |||

| Employed/Self-Employed | 46 (69.7%) | 40 (74.1%) | 6 (50.0%) |

| Unemployed | 14 (21.2%) | 11 (20.5%) | 3 (25.0%) |

| Other/Student | 5 (7.6) | 2 (3.7%) | 3 (25.5%) |

| Income | |||

| $0 | 9 (13.6%) | 5 (9.3%) | 4 (33.3%) |

| $1–24,999 | 26 (39.4%) | 19 (35.2%) | 7 (58.3%) |

| $25,000–49,999 | 19 (28.8%) | 13 (24.1%) | 1 (8.3%) |

| $50,000–74,999 | 8 (12.1%) | 8 (14.8%) | 0 |

| $75,000–99,999 | 2 (3.0%) | 2 (3.7%) | 0 |

| ≥$100,000 | 2 (3.0%) | 2 (3.7%) | 0 |

| Marital Status | |||

| Married/Partnered | 26 (39.2%) | 25 (46.3%) | 1 (8.3%) |

| Never Married | 37 (56.1%) | 26 (48.1%) | 11 (91.7%) |

| Separated/Divorced | 3 (4.5%) | 3 (5.6%) | 0 |

| Pretreatment Principal Diagnosis | |||

| GAD/OAD | 37 (56.1%) | 32 (59.3%) | 5 (41.7%) |

| SP/AV | 18 (27.3%) | 11 (20.4%) | 7 (58.3%) |

| SAD | 11 (16.7%) | 11 (20.4%) | 0 |

| Posttreatment Response | |||

| Principal No Longer Present | 40 (60.6%) | 32 (59.3%) | 8 (66.7%) |

Note. RCT-2=Subjects previously randomized to treatment in Kendall et al., 1997. RCT-3= Subjects previously randomized to treatment in Kendall et al., 2008. GAD/OAD=Generalized Anxiety Disorder/Overanxious Disorder of Childhood. SP/AV=Social Phobia/Avoidant Disorder. SAD=Separation Anxiety Disorder. Principal No Longer Present=Pretreatment principal diagnosis was no longer present anywhere in the diagnostic profile at posttreatment.

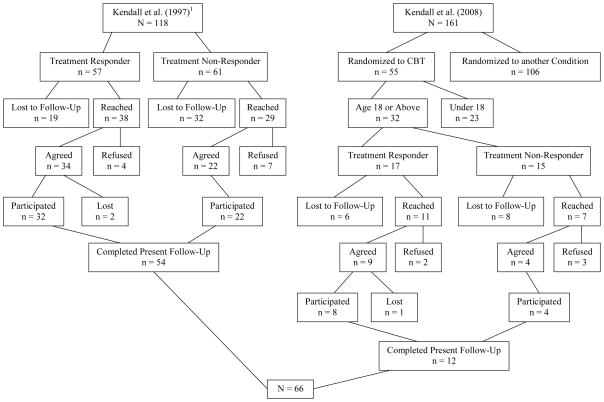

Of the 150 individuals who were eligible to participate in the present study, 66 were located and participated, 16 were located and declined participation, three were initially reached and agreed to participate and then became unreachable prior to study participation, and 35 could not be located (i.e., all leads were exhausted). For the remaining 30 individuals, possible contact information was identified; however, the individuals and/or their parents were never reached directly despite multiple attempts. See Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Participant flow chart illustrating response rate through the recruitment and interviewing processes.

1Participants from Kendall et al. (1997) included 94 participants who completed the initial randomized clinical trial, as well as 24 additional participants who were in the intent-to-treat sample. Of these 24, attrition included 9 from treatment, 9 from waitlist, and 6 from treatment after waitlist.

Assessment Instruments

The World Mental Health Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI), the interview used in the National Comorbidity Survey- Replication study (NCS-R; Kessler et al., 2005), was chosen to allow comparisons between the sample of previously treated anxious youth and the NCS-R community sample (Kessler et al., 2005). Self-report measures were also gathered to compare the successfully treated and unsuccessfully treated participants.

Structured Diagnostic Interview

World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative Version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI; Robins et al., 1988; Kessler & Ustun, 2004)

The CIDI is a fully structured comprehensive lifetime interview designed to obtain information on mood disorders, anxiety disorders, SUDs, and other relevant disorders. It is appropriate for administration by trained lay interviewers. Diagnoses are based on and consistent with DSM-IV (APA, 1994) and ICD-10 (WHO, 1992). This interview also assesses demographic variables (e.g., marital and occupational status, income) and subsequent treatment. CIDI diagnoses are significantly related to independent clinical diagnoses, and test-retest reliability is high (Kessler & Ustun, 2004).

Participant Self-Report Measures

Drug Use Screening Inventory-Revised (DUSI-R; Tarter, 1990)

The DUSI-R is a self-report 159-item questionnaire that assesses severity of problems and consequences over the past week and past year in 10 domains for adolescents and adults: Substance abuse (for a variety of drugs), psychiatric disorders, behavior problems, school adjustment, health status, work adjustment, peer relations, social competency, family adjustment, and leisure/recreation. It also contains a 10-item lie scale to estimate validity of responses. The DUSI-R has demonstrated internal consistency, temporal stability, and concurrent validity (Kirisci, Mezzich, & Tarter, 1995).

Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI; Beck, Epstein, Brown, & Steer, 1988)

The BAI is a 21-item self-report questionnaire that assesses the frequency and severity of anxiety symptomatology over one week. Each item is rated on a 4-point scale: 0 (not at all) to 3 (severely, I could barely stand it). The BAI is comprised of two main dimensions of anxiety: cognitive and physiological (or somatic) symptoms. The BAI has been shown to have good internal consistency, retest reliability, and convergent and discriminant validity (Beck et al., 1988; Beck & Steer, 1991; Hewitt & Norton, 1993).

Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II; Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996)

The BDI-II is a 21-item measure of depressive symptoms experienced during the past two weeks. Each item has four statements that reflect varying degrees of symptom severity. Similar to the BAI, the BDI-II loads onto two dimensions of depression: cognitive and somatic symptoms. The BDI-II has demonstrated excellent internal consistency, factorial validity, criterion validity, convergent and discriminant validity, and internal reliability in numerous samples with varying ethnicity and psychopathology (Arnau, Meagher, Norris, & Bramson, 2001; Carmody, 2005; Contreras, Fernandez, Malcarne, Ingram, & Vaccarino, 2004; Dozois, Dobson, & Ahnberg, 1998; Grothe et al., 2005; Storch, Roberti, & Roth, 2004; Weeks & Heimberg, 2005).

Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS; Sheehan, 1983)

The SDS is a frequently used self-report disability measure, consisting of four items measuring current impaired functioning across three domains: Social Life/Leisure Activities, Work, Family Life/Home Responsibilities, and Work and Social Disability change of symptoms. Each item is rated on a scale from 0 (Not at all) to 10 (Very severely – I never do these) of increasing impairment, except for the fourth item which is rated on a scale from 1 (No complaints, normal activity) to 5 (Symptoms radically change/prevent normal work or social activities). The SDS has demonstrated adequate to high internal consistency, satisfactory construct validity, and criterion-related validity in multiple psychiatric populations and primary care patients (Hambrick, Turk, Heimberg, Schneier, & Liebowitz, 2004; Leon, Olfson, Portera, Farber, & Sheehan, 1997; Leon, Shear, Portera, & Klerman, 1992; Placchi, 1997; Rubin et al., 2000).

Quality of Life Inventory (QOLI; Frisch, Cornell, Villanueva, & Retzlaff, 1992)

The QOLI is a brief, 32-item, self-report questionnaire that assesses life satisfaction across 16 domains (e.g., love, work, health, friends, family, self-esteem) and is weighted by the relative importance of each domain to the individual (Frisch, 2004). The QOLI has been found to have adequate item-total correlations, strong convergent and discriminant validity, and high criterion validity between clinical and nonclinical samples (Frisch et al., 1992).

Clinician Rated Measure

Participant Additional Treatment (PAT)

A rating scale was developed to quantify additional treatment obtained since initial study participation. After reviewing services reported on the CIDI interview for each participant, diagnosticians at the CAADC independently rated the degree to which the participant “received additional services” on a 0 to 4 likert scale. The principal investigator served as the expert judge of additional treatment ratings and the other raters were required to match her ratings on three sample interviews prior to rating study participants at a kappa level of .80 or above. Raters were also subject to a random check during the rating period to ensure that the reliability ratings of additional treatment remained above .80.

Study Procedures

The present study was approved by and conducted in compliance with the Temple University Institutional Review Board. The study team attempted to reach participants using contact information provided at the start of the initial RCTs and/or updated at previous follow-ups. During initial participation, the child provided written assent and their parent(s) provided written consent. Participants who were able to be reached directly were asked to participate in the current study following a description of the project. If a participant was currently living separately from his or her family and the contact sheet provided information about the parent’s residence, we described the project to the parent and asked the parent to contact their child for permission to provide us with the child’s direct contact information.

All local participants were invited to participate in one 3–4 hour evaluation in person (n = 9). Those who had moved out of the immediate region or expressed difficulty with coming to the research lab were invited to participate via phone and internet (n = 57). Prior to any participation, participants were asked to sign informed consent. Compensation in the form of a gift card was provided to participants for their time. All interviewers completed a group didactic training session and independently reviewed study materials. CIDI Interviewers and PAT raters were blind to initial treatment response, and PAT raters were blind to participants’ responses at the present follow-up (with the exception of data pertaining to additional treatment received).

Results

Preliminary analyses compared long-term follow-up study participants with nonparticipants (those unable to be contacted or unwilling to participate in the present study) to examine differences on initial demographic variables and pre- and post-treatment dependent measures. Participation was not significantly associated with gender (χ2 (1) = 2.45, p = .12), race (χ2 (4) = 4.73, p = .32), or pretreatment principal diagnosis (χ2 (2) = 1.15, p = .56). One-way analysis of variance comparing participants versus nonparticipants on child age was also not significant, F (1, 151) = 1.05, p = .31. Chi-square analysis comparing participants versus nonparticipants by treatment response was non-significant (χ2 (1) = 1.75, p = .19)3.

Results from the diagnostic interview administered during the present long-term follow-up study indicated that 43.9% (n = 29) of individuals met DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for one or more lifetime anxiety disorder with onset of age 18 or older, or with onset in childhood and duration persisting into adulthood. Anxiety disorders included are as follows: GAD (16.7%, n = 11), SP (25.8%, n = 18), SAD (7.6%, n = 5), Panic Disorder (9.1%, n = 6), Agoraphobia (6.1%, n = 4), Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (7.6%, n =5), and/or Specific Phobia (17.4%, n = 12). Additionally, 27.3% (n = 18) met criteria for one or more depressive disorder, including Major Depressive Disorder (27.3%, n = 18) and Dysthymic Disorder (3.0%, n = 2). Finally, 42.4% (n = 28) met criteria for one or more SUD including Alcohol Abuse (24.2%, n = 16), Alcohol Dependence (9.1%, n = 6), Drug Abuse (13.6%, n = 9), Drug Dependence (3.0%, n = 2), and/or Nicotine Dependence (27.3%, n = 18)4.

Participants completed ratings of current mood, anxiety, and substance use symptomology as well as quality of life and overall disability/impairment. Overall means were: BDI-II = 10.62 (SD = 11.63), BAI = 9.62 (SD = 9.62), SDS Disability Score = 20.3 (SD = 1.12), QOLI Total = 24.72 (SD = 24.89), and DUSI-R Problem Density Index = 20.58 (SD = 13.99). Mean self-report form scores were not significantly different when examined by outcome status (successful/unsuccessful as indicated by posttreatment diagnostic status) for the BDI-II (t(61) = 1.33, p = .19), BAI (t(61) = 1.22, p = .23), SDS (t(61) = .95, p = .35), QOLI (t(59) = −.79, p = .43), and DUSI-R (t(59) = 1.37, p = .18) indicating that successful treatment response was not associated with ratings of adult state depression, state anxiety, disability/impairment, quality of life, or self-report ratings of substance misuse symptomology.

Primary Analyses: Effects of Treatment on Sequelae of Anxiety

To test the effect of previous treatment outcome on the sequelae of anxiety, logistic regressions examined whether outcome status (successful/unsuccessful as indicated by posttreatment diagnostic status) predicts adult anxiety, depressive disorder and subsequent SUDs (i.e., if participants meet diagnostic criteria for any anxiety disorder(s) on the CIDI interview with an onset age ≥ 18 years or onset in childhood persisting into adulthood, they were considered to have an adult anxiety disorder). Time since initial study treatment in months was included as a covariate.

Unsuccessful treatment (defined as the principal anxiety disorder still present at posttreatment) significantly predicted the presence of adult Panic Disorder, with an odds ratio of 9.34. Additionally, unsuccessful treatment significantly predicted the presence of adult Alcohol Dependence, demonstrating an odds ratio of 9.42, as well as Drug Abuse, with an odds ratio of 7.00. All other logistic regressions predicting anxiety disorders, depressive diagnoses, and SUDs were non-significant (see Table 2)5.

Table 2.

Logistic Regressions Examining Treatment Response as a Predictor of DSM-IV Disorders at 16-Year Follow-Up, Controlling for Months since Initial Treatment

| B (SE) | 95% CI for Odds Ratio

|

p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Odds Ratio | Upper | |||

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder | |||||

| Constant | 1.04 (1.52) | ||||

| Time Since Treatment | .00 (.01) | .99 | 1.00 | 1.02 | .78 |

| Treatment Response | .30 (.67) | .37 | 1.35 | 4.98 | .66 |

| Social Phobia | |||||

| Constant | .12 (1.35) | ||||

| Time Since Treatment | .00 (.01) | .99 | 1.00 | 1.02 | .79 |

| Treatment Response | 1.08 (.58) | .95 | 2.95 | 9.18 | .06 |

| Separation Anxiety Disorder | |||||

| Constant | 9.33 (8.90) | ||||

| Time Since Treatment | −.04 (.04) | .89 | .97 | 1.05 | .40 |

| Treatment Response | .1.01 (.98) | .40 | 2.74 | 18.54 | .30 |

| Panic Disorder1 | |||||

| Constant | 1.89 (2.26) | ||||

| Time Since Treatment | −.00 (.01) | .98 | 1.00 | 1.02 | .83 |

| Treatment Response | 2.23 (1.13) | 1.02 | 9.34 | 85.13 | .05 |

| Agoraphobia | |||||

| Constant | 17.74 (15.08) | ||||

| Time Since Treatment | −.07 (.07) | .81 | .93 | 1.07 | .30 |

| Treatment Response | .71 (1.10) | .23 | 2.03 | 17.59 | .52 |

| Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder | |||||

| Constant | 6.85 (6.46) | ||||

| Time Since Treatment | −.03 (.03) | .92 | .98 | 1.04 | .41 |

| Treatment Response | 2.04 (1.16) | .78 | 7.65 | 74.84 | .08 |

| Specific Phobia | |||||

| Constant | 2.04 (1.68) | ||||

| Time Since Treatment | −.00 (.01) | .98 | 1.00 | 1.01 | .71 |

| Treatment Response | .12 (.65) | .32 | 1.13 | 4.02 | .86 |

| Major Depressive Disorder | |||||

| Constant | 2.30 (1.60) | ||||

| Time Since Treatment | −.01 (.01) | .98 | .99 | 1.01 | .33 |

| Treatment Response | .30 (.57) | .45 | 1.35 | 4.07 | .60 |

| Dysthymic Disorder | |||||

| Constant | 68.86 (42.86) | ||||

| Time Since Treatment | −.30 (.19) | .51 | .74 | 1.08 | .12 |

| Treatment Response | 1.74 (1.78) | .47 | 5.71 | 187.99 | .33 |

| Alcohol Abuse | |||||

| Constant | 1.29 (1.47) | ||||

| Time Since Treatment | −.00 (.01) | .98 | 1.00 | 1.01 | .73 |

| Treatment Response | .58 (.58) | .57 | 1.78 | 5.57 | .32 |

| Alcohol Dependence2 | |||||

| Constant | 2.75 (2.64) | ||||

| Time Since Treatment | −.01 (.01) | .97 | .99 | 1.02 | .61 |

| Treatment Response | 2.24 (1.13) | 1.03 | 9.42 | 86.34 | .05 |

| Drug Abuse3 | |||||

| Constant | .68 (1.72) | ||||

| Time Since Treatment | .00 (.01) | .99 | 1.00 | 1.02 | .85 |

| Treatment Response | 1.95 (.85) | 1.32 | 7.00 | 37.02 | .02 |

| Drug Dependence | |||||

| Constant | 34.20 (26.97) | ||||

| Time Since Treatment | −.15 (.12) | .68 | .86 | 1.10 | .23 |

| Treatment Response | 19.14 (5521.41) | .00 | 206093130.00 | - | 1.00 |

| Nicotine Dependence | |||||

| Constant | .67 (1.30) | ||||

| Time Since Treatment | .00 (.01) | .99 | 1.00 | 1.02 | .65 |

| Treatment Response | −.36 (.58) | .22 | .70 | 2.18 | .54 |

Note: Time Since Treatment = Months since initial study treatment. Treatment Response = Treatment outcome defined as the principal disorder at pretreatment no longer present at posttreatment.

R2=.08 (Cox & Snell), .17 (Nagelkerke). Model χ2(2)=5.45, p = .07

R2=.08 (Cox & Snell), .18 (Nagelkerke). Model χ2(2)=5.71, p = .06.

R2=.09 (Cox & Snell), .17 (Nagelkerke). Model χ2(2)=6.44, p < .05.

Chi-square analysis examined the association between posttreatment diagnostic status and the presence of the primary pretreatment disorder at the time of the present long-term follow up. Results were non-significant, χ2 (1) = .56, p = .45.

Effects of Posttreatment Diagnostic Status on Additional Treatment

Additional therapeutic services after initial study treatment were examined dichotomously (i.e., presence or absence of additional treatment) as well as continuously (PAT clinician-rated measure). When additional treatment was defined as presence or absence of additional treatment, 93.9% (n = 62) of participants endorsed receiving at least some additional services. When additional services were coded by experienced diagnosticians, 4 (6.1%) individuals received no additional services, 16 (24.2%) obtained some additional services, 20 (30.3%) obtained a moderate amount of additional services, 18 (27.3%) received a great deal of additional services, and 8 (12.1%) were rated as receiving services more often than not since initial treatment completion.

When additional services were examined dichotomously using logistic regression, responder status did not significantly predict additional services (B (SE) = 1.63 (1.18), Odds Ratio = 5.09, p = .17). When additional services were examined continuously (PAT data) using linear regression, responder status did not significantly predict additional services (β = .02, p = .99, R2 < .01).

Secondary Analyses: Normative Comparisons

For purposes of normative comparison (Kendall, Marrs-Garcia, Nath, & Sheldrick, 1999), successfully treated and unsuccessfully treated participants were compared to a subsample of same-age community participants from the NCS-R (n = 2676; Kessler et al., 2005) on diagnostic status of anxiety, mood, and SUDs. Logistic models were used. Included in the model were three groups: successfully treated participants, unsuccessfully treated participants, and the comparison group (NCS-R). Follow-up tests, according to Dunnett’s criterion, were conducted comparing the treatment groups with the comparison group provided an overall effect was seen. Age was included as a covariate.

Successful treatment group status significantly predicted GAD, SP, and Panic Disorder. Regarding SP and Panic Disorder, follow-up tests indicated the unsuccessfully treated participants demonstrated significantly higher rates of SP (p < .01) and Panic Disorder (p <.01) than the normative comparison group and successfully treated participants did not significantly differ from the normative group for these disorders. With respect to GAD, both successfully (p = .02) and unsuccessfully treated participates (p < .01) had higher rates of GAD than the normative group. See Table 3.

Table 3.

Logistic Regressions Comparing Successful Treatment Response, Unsuccessful Treatment Response, and Same-Age Community Participants on DSM-IV Anxiety Disorder Diagnoses Controlling for Age

| B (SE) | 95% CI for Odds Ratio

|

p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Odds Ratio | Upper | |||

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder1 | |||||

| Constant | 3.94 (.50) | ||||

| Age | −.04 (.02) | .92 | .96 | .99 | .02 |

| Normative Comparison Group | .00 | ||||

| Principal Still Present | −1.30 (.51) | .10 | .27 | .74 | .01 |

| Principal No Longer Present | −.99 (.45) | .15 | .37 | .90 | .03 |

| Social Phobia2 | |||||

| Constant | 2.88 (.35) | ||||

| Age | −.04 (.01) | .94 | .96 | .99 | .01 |

| Normative Comparison Group | <.01 | ||||

| Principal Still Present | −1.40 (.41) | .11 | .25 | .55 | <.01 |

| Principal No Longer Present | −.31 (.42) | .32 | .74 | 1.68 | .47 |

| Separation Anxiety Disorder | |||||

| Constant | 1.72 (.41) | ||||

| Age | .03 (.02) | 1.00 | 1.03 | 1.07 | .07 |

| Normative Comparison Group | .61 | ||||

| Principal Still Present | −.50 (.62) | .18 | .60 | 2.04 | .42 |

| Principal No Longer Present | .40 (.73) | .36 | 1.49 | 6.25 | .58 |

| Panic Disorder3 | |||||

| Constant | 4.34 (.56) | ||||

| Age | −.05 (.02) | .91 | .95 | .99 | .02 |

| Normative Comparison Group | .01 | ||||

| Principal Still Present | −1.48 (.51) | .08 | .23 | .62 | <.01 |

| Principal No Longer Present | .76 (1.02) | .29 | 2.13 | 15.66 | .46 |

| Agoraphobia | |||||

| Constant | 4.72 (.78) | ||||

| Age | −.04 (.03) | .91 | .96 | 1.02 | .21 |

| Normative Comparison Group | .17 | ||||

| Principal Still Present | −1.22 (.75) | .07 | .30 | 1.29 | .11 |

| Principal No Longer Present | −.75 (.74) | .11 | .47 | 2.01 | .31 |

| Specific Phobia | |||||

| Constant | 2.49 (.33) | ||||

| Age | −.03 (.01) | .95 | .98 | 1.00 | .05 |

| Normative Comparison Group | .67 | ||||

| Principal Still Present | −.36 (.50) | .26 | .70 | 1.88 | .48 |

| Principal No Longer Present | −.24 (.42) | .35 | .79 | 1.80 | .58 |

Note. Normative Comparison Group=Participants from the National Comorbidity Survey-Replication study (NCS-R; Kessler et al., 2005). Principal Still Present=Treatment nonresponder (i.e., pretreatment principal diagnosis remained in diagnostic profile at posttreatment). Principal No Longer Present=Treatment responder (i.e., pretreatment principal diagnosis was no longer present anywhere in the diagnostic profile at posttreatment).

Dunnetts t comparing Normative Comparison Group and Principal Still Present= p < .01

Dunnetts t comparing Normative Comparison Group and Principal No Longer Present = p = .02

Dunnetts t comparing Normative Comparison Group and Principal Still Present= p < .01

Dunnetts t comparing Normative Comparison Group and Principal No Longer Present = p = .59

Dunnetts t comparing Normative Comparison Group and Principal Still Present= p < .01

Dunnetts t comparing Normative Comparison Group and Principal No Longer Present = p = .77

Group status did not significantly predict any depressive disorders (Major Depressive Disorder, B (SE) = −.53 (.37), Odds Ratio = .59, p = .15; Dysthymic Disorder, B (SE) = .30 (.18), Odds Ratio = 1.36, p = .77). Group status significantly predicted Alcohol Abuse, Alcohol Dependence, Drug Abuse, and Nicotine Dependence. Follow-up tests indicated that the unsuccessfully treated participants had significantly higher rates of Alcohol Abuse (p <.01), Alcohol Dependence (p <.01), and Drug Abuse (p < .01) than the normative group. Successfully treated participants did not significantly differ from the normative group for these diagnoses. Regarding Nicotine Dependence, both successfully (p < .01) and unsuccessfully treated participates (p < .01) had significantly higher rates of Nicotine Dependence than the normative group. See Table 4.

Table 4.

Logistic Regressions Comparing Successful Treatment Response, Unsuccessful Treatment Response, and Same-Age Community Participants on DSM-IV Substance Use Disorder Diagnoses Controlling for Age

| B (SE) | 95% CI for Odds Ratio

|

p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Odds Ratio | Upper | |||

| Alcohol Abuse1 | |||||

| Constant | 3.04 (.36) | ||||

| Age | −.04 (.01) | .94 | .96 | .99 | <.01 |

| Normative Comparison Group | .01 | ||||

| Principal Still Present | −1.17 (.43) | .13 | .31 | .72 | <.01 |

| Principal No Longer Present | −.59 (.40) | .25 | .56 | 1.22 | .14 |

| Alcohol Dependence2 | |||||

| Constant | 4.49 (.53) | ||||

| Age | −.06 (.02) | .90 | .94 | .98 | <.01 |

| Normative Comparison Group | .02 | ||||

| Principal Still Present | −1.32 (.51) | .10 | .27 | .72 | <.01 |

| Principal No Longer Present | .92 (1.02) | .34 | 2.51 | 18.43 | .37 |

| Drug Abuse3 | |||||

| Constant | 2.36 (.41) | ||||

| Age | .00 (.02) | .97 | 1.00 | 1.03 | .90 |

| Normative Comparison Group | .01 | ||||

| Principal Still Present | −1.41 (.45) | .01 | .24 | .59 | <.01 |

| Principal No Longer Present | .53 (.73) | .41 | 1.70 | 7.12 | .47 |

| Drug Dependence | |||||

| Constant | 4.13 (.65) | ||||

| Age | −.03 (.03) | .93 | .97 | 1.02 | .25 |

| Normative Comparison Group | .51 | ||||

| Principal Still Present | −.86 (.75) | .10 | .42 | 1.82 | .25 |

| Principal No Longer Present | 17.86 (6351.32) | .00 | 57025267.77 | 1.00 | |

| Nicotine Dependence4 | |||||

| Constant | 2.94 (.46) | ||||

| Age | −.01 (.02) | .96 | .99 | 1.03 | .65 |

| Normative Comparison Group | <.01 | ||||

| Principal Still Present | −1.51 (.47) | .09 | .22 | .56 | <.01 |

| Principal No Longer Present | −1.87 (.36) | .08 | .15 | .31 | <.01 |

Note. Normative Comparison Group=Participants from the National Comorbidity Survey-Replication study (Kessler et al., 2005). Principal Still Present=Treatment nonresponder (i.e., pretreatment principal diagnosis remained in diagnostic profile at posttreatment). Principal No Longer Present=Treatment responder (i.e., pretreatment principal diagnosis was no longer present anywhere in the diagnostic profile at posttreatment).

Dunnetts t comparing Normative Comparison Group and Principal Still Present= p < .01

Dunnetts t comparing Normative Comparison Group and Principal No Longer Present = p = .17

Dunnetts t comparing Normative Comparison Group and Principal Still Present= p < .01

Dunnetts t comparing Normative Comparison Group and Principal No Longer Present = p = .67

Dunnetts t comparing Normative Comparison Group and Principal Still Present= p < .01

Dunnetts t comparing Normative Comparison Group and Principal No Longer Present = p = .71

Dunnetts t comparing Normative Comparison Group and Principal Still Present= p < .01

Dunnetts t comparing Normative Comparison Group and Principal No Longer Present = p < .01

Discussion

The present study is the first to examine a long-term (> 16 years on average) follow-up of CBT for childhood anxiety disorders on anxiety, depression, and substance misuse in young adulthood when these disorders are likely to become evident. Results indicate that, relative to those who respond successfully to CBT for an anxiety disorder in childhood, those who were less responsive had higher rates of panic disorder, alcohol dependence, and drug abuse in adulthood. These findings were mostly consistent when factors such as pretreatment principal anxiety diagnosis, time since initial treatment, and subsequent treatment were included in the models. Knowledge about advantageous effects of an anxiety intervention on general mental health offers important insight regarding prevention of secondary disorders by treating a primary disorder (Kessler & Price, 1993).

Given the high lifetime co-occurrence of anxiety and SUDs (35% to 45%; Kessler et al., 1996) and their associated deleterious outcomes (e.g., Toumbourou et al., 2007), the indication that childhood anxiety disorders may serve as a gateway disorder for later substance misuse is particularly compelling and warrants further investigation. Evidence suggests that as much as 60% of adult substance dependence may be prevented by early treatment of disorders in youth (Kendall & Kessler, 2002; Kessler et al., 2001), and CBT in particular holds promise as a tool for preventing the development of secondary substance use comorbidities in youth with anxiety. Given that CBT for child anxiety is a feasible, cost-effective, and acceptable method of intervention, its utility in preventing the development of negative sequelae warrants continued effort and investigation.

The literature suggests that childhood anxiety disorders predict adult anxiety, depression and SUDs; however, the present results were unexpected in that no depressive disorders were predicted by unsuccessful treatment and panic disorder was the only anxiety disorder predicted by initial study treatment outcome. Furthermore, treatment non-responders were no more likely than treatment responders to meet diagnostic criteria for their same primary childhood pretreatment diagnosis at the time of this follow-up. These results suggest that the risk factors for untreated childhood anxiety versus unsuccessfully treated child anxiety may vary. Treatment response was also not associated with self-report of disability/impairment nor with quality of life, a noteworthy finding given previous research indicating that young adults with a history of childhood anxiety have more difficulty transitioning to independent living (Last, Hansen, & Franco, 1997).

The current study compared successfully and unsuccessfully treated participants a mean of 16.24 years after treatment to same-aged individuals from the general population (i.e., NCS-R sample; Kessler et al., 2005) on rates of anxiety, mood, and SUDs. Consistent with hypotheses, the unsuccessfully (but not successfully) treated group had higher rates of SP, Panic Disorder, Alcohol Abuse, Alcohol Dependence, and Drug Abuse than the normative comparison group. These results provide preliminary evidence that those who do not have a successful treatment response to CBT for a childhood anxiety disorder remain at increased risk for associated anxiety (in particular, SP and Panic Disorder) and SUDs (in particular, Alcohol Abuse and Dependence) long-term relative to their same-aged peers. Additionally, those who have a successful treatment response early on do not appear to confer greater risk for these disorders in adulthood than the general population.

Two exceptions to the above findings exist with respect to GAD and Nicotine Dependence. Both the successfully and unsuccessfully treated groups had higher rates of GAD and Nicotine Dependence than the normative comparison group. Though these results require replication, they suggest that the benefits of childhood CBT for anxiety may not be as protective long-term for these particular disorders. Future studies to explore factors that may account for higher rates of GAD and Nicotine Dependence among anxious youth are needed.

Given that this was not a prospective study, it is difficult to know for certain whether the successful treatment itself is related to better outcomes or if treatment outcome is a proxy for other factors. Participants were not restricted from obtaining additional services during the follow-up interval, a limitation of studies of this nature. Possible risk and protective factors that may contribute to the relationship between treatment outcome and long-term status may include child intellect and motivation, psychosocial stressors, and duration of illness at initial treatment presentation. Future longitudinal, prospective studies that adopt a developmental psychopathology perspective to examine these and other important risk and protective factors are needed. Other limitations include a modest response rate and a sample that was predominantly Caucasian, middle to high SES, and college educated. Future treatment outcome studies would benefit from including diverse samples.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant to Courtney L. Benjamin (MH086954) and facilitated by grants awarded to Philip C. Kendall (MH063747; MH086438) from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Note, however, that the original 118 children were selected using the following criteria: (a) children had to have a DSM anxiety disorder (GAD, SP, SAD) as a principal diagnosis; (b) children whose principal diagnosis was simple phobia (or phobias) were not included, but children with diagnosable specific phobias as secondary problems were included; (c) children were excluded if they displayed psychotic symptoms; or (d) if they were using anti-anxiety or anti-depressant medications at the time of intake.

Note, however, that the original sample was selected using the following criteria: (a) children had to have a DSM anxiety disorder (GAD, SP, SAD) as a principal diagnosis; (b) children whose principal diagnosis was simple phobia (or phobias) were not included, but children with diagnosable specific phobias as secondary problems were included; (c) children were required to have at least one English speaking parent; (d) children were excluded if they displayed psychotic symptoms; (e) had a disabling medication condition; (f) mental retardation; (g) if they were using anti-anxiety or anti-depressant medications at the time of intake; or (h) were participating in concurrent treatment.

Subjects who participated in person were also compared to subjects who participated by phone on the same key demographic and treatment variables. No significant differences were observed.

While not the focus of the present study, seven participants met criteria for lifetime diagnoses of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, five for oppositional defiant disorder, four for posttraumatic stress disorder, three for conduct disorder, and one for bulimia. No participants met criteria for lifetime diagnoses of Bipolar I or Bipolar II disorders, anorexia, or intermittent explosive disorder.

Follow-up tests examined if the significant relationships between treatment response and adult disorders reported above held when we included primary diagnosis at time of additional treatment presentation, additional treatment, and age, as covariates. No consistent significant relationships with outcome at follow-up were observed.

References

- Alpert JE, Maddocks A, Rosenbaum JF, Fava M. Childhood psychopathology retrospectively assessed among adults with early onset major depression. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1994;31:165–171. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(94)90025-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Angold A, Costello E, Erkanli A. Comorbidity. Journal of Child Psychological Psychiatry. 1999;40:57–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnau RC, Meagher MW, Norris MP, Bramson R. Psychometric evaluation of the Beck Depression Inventory-II with primary care medical patients. Health Psychology. 2001;20:112–119. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.20.2.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett P, Dadds M, Rapee R. Family treatment of childhood anxiety: a controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64:333–342. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.2.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett P, Duffy A, Dadds M, Rapee R. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of anxiety disorders in children: Long-term (6-year) follow-up. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69:135–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, Steer RA. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: Psychometric properties. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1988;56:893–897. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.6.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA. Relationship between the Beck Anxiety Inventory and the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale with anxious outpatients. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 1991;5:213–223. [Google Scholar]

- Beck A, Steer R, Brown G. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Beesdo K, Bittner A, Pine DS, Stein MB, Hofler M, Lieb R, et al. Incidence of social anxiety disorder and the consistent risk for secondary depression in the first three decades of life. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64:903–912. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.8.903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beidel DC, Turner SM, Sallee FR, Ammerman RT, Crosby LA, Pathak S. SET-C versus fluoxetine in the treatment of childhood social phobia. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2007;46:1622–1632. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e318154bb57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beidel DC, Turner SM, Young B, Paulson A. Social effectiveness therapy for children: Three-year follow-up. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;17:721–725. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.4.721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beidel DC, Turner SM, Young BJ. Social effectiveness therapy for children: Five years later. Behavior Therapy. 2006;37:416–425. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2006.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein GA, Borchardt CM. Anxiety disorders of childhood and adolescents: A review. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1991;30:519–532. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199107000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Faraone S, Mick E, Lelon E. Psychiatric comorbidity among referred juveniles with major depression: Fact or artifact? Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1995;34:579–590. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199505000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brent DA, Kalas R, Edelbrock C, Costello AJ, Dulcan MK, Conover N. Psychopathology and its relationship to suicidal ideation in childhood and adolescence. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry. 1986;25:666–673. doi: 10.1016/s0002-7138(09)60292-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmody DP. Psychometric characteristics of the Beck Depression Inventory-II with college students of diverse ethnicity. International Journal of Psychiatry in Clinical Practice. 2005;9:22–28. doi: 10.1080/13651500510014800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambless D, Hollon S. Defining empirically supported treatments. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:5–17. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavira D, Stein M, Bailey K, Stein M. Child anxiety in primary care: Prevalent but untreated. Depression and Anxiety. 2004;20:155–164. doi: 10.1002/da.20039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for behavioral sciences. NY: Academic Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Contreras S, Fernandez S, Malcarne VL, Ingram RE, Vaccarino VR. Reliability and validity of the Beck Depression and Beck Anxiety Inventories in Caucasian Americans and Latinos. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2004;26:446–462. [Google Scholar]

- Costello E, Mustillo S, Erkanli A, Keeler G, Angold A. Prevalence and development of psychiatric disorders in childhood and adolescence. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60:837–844. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.8.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello E, Mustillo S, Keeler G, Angold A. Prevalence of Psychiatric Disorders in Children and Adolescents. In: Levine B, Petrila J, Hennessey K, editors. Mental Health Services: A Public Health Perspective. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2004. pp. 111–128. [Google Scholar]

- Curry J, Silva S, Rohde P, Ginsburg G, Kennard B, Kratochvil C, et al. Onset of alcohol or substance use disorders following treatment for adolescent depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2012;80:299–312. doi: 10.1037/a0026929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dozois DJA, Dobson KS, Ahnberg JL. A psychometric evaluation of the Beck Depression Inventory-II. Psychological Assessment. 1998;10:83–89. [Google Scholar]

- Finney JW, Moos RH. The long-term course of treated alcoholism, II: Predictors and correlates of 10-year functioning and mortality. Journal of the Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 1992;53:142–153. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1992.53.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch M. Use of the QOLI® or Quality of Life Inventory-super(TM) in quality of life therapy and assessment. In: Maruish M, editor. The use of psychological testing for treatment planning and outcomes assessment, Volume 3: Instruments for adults. 3. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Lopez LJ, Olivares J, Beidel D, Albano AM, Turner S, Rosa A. Efficacy of three treatment protocols for adolescents with social anxiety disorder: A 5-year follow-up assessment. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2006;20:175–191. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2005.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grothe KB, Dutton GR, Jones GN, Bodenlos J, Ancona M, Brantley PJ. Validation of the Beck Depression Inventory-II in a low-income African American sample of medical outpatients. Psychological Assessment. 2005;17:110–114. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.17.1.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hambrick JP, Turk CL, Heimberg RG, Schneier FR, Liebowitz MR. Psychometric properties of disability measures among patients with social anxiety disorder. Anxiety Disorders. 2004;18:825–839. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2003.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt PL, Norton GR. The Beck Anxiety Inventory: A psychometric analysis. Psychological Assessment. 1993;5:408–412. [Google Scholar]

- Hirshfeld-Becker DR, Micco JA, Simoes NA, Henin A. High risk studies and developmental antecedents of anxiety disorders. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part C (Seminars in Medical Genetics) 2008;148C:99–117. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollon SD, Beck AT. Cognitive and cognitive-behavioral therapies. In: Lambert M, editor. Bergin and Garfield’s Handbook of psychotherapy and behavior change. 6. New York: Wiley; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard RL, Craddock G, Flynn PM, Anderson J, Etheridge R. Overview of 1-year follow-up outcomes in the Drug Abuse Treatment Outcome Study (DATOS) Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1997;11:261–278. [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE, Siegel T, Bass D. Cognitive problem-solving skills training and parent management training in the treatment of antisocial behavior in children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1992;60:733–740. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.60.5.733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE, Weisz JR. Identifying and developing empirically supported child and adolescent treatments. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:19–36. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC, Flannery-Schroeder E, Panicelli-Mindel SM, Southam-Gerow MA, Henin A, Warman M. Therapy for youths with anxiety disorders: A second randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65:366–380. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.3.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC, Hedtke K. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxious children: Therapist manual. 3. Ardmore, PA: Workbook Publishing; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC, Hudson JL, Gosch E, Flannery-Schroeder E, Suveg C. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety disordered youth: A randomized clinical trial evaluating child and family modalities. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76:282–297. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.2.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC, Kessler RC. The impact of childhood psychopathology interventions on subsequent substance abuse: Policy implications, comments, and recommendations. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:1303–1306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC, Marrs-Garcia A, Nath S, Sheldrick RC. Normative comparisons for the evaluation of clinical significance. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67:285–299. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.3.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC, Safford S, Flannery-Schroeder E, Webb A. Child anxiety treatment: Outcomes in adolescence and impact on substance use and depression at 7.4-year follow-up. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:276–287. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.2.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Andrade L, Bijl R, Borges G, Caraveo-Anduaga JJ, et al. Mental-substance comorbidities in the ICPE surveys. Psychiatria Fennica. 2001;32(Suppl 2):62–80. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Walters E. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Archives General Psychiatry. 2005;62:593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R, Chiu W, Demler O, Walters E. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Archives General Psychiatry. 2005;62:617–627. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Nelson C, McGonagle K, Edlund M, Frank R, Leaf P. The epidemiology of co-occurring addictive and mental disorders: Implications for prevention and service utilization. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1996;66:17–31. doi: 10.1037/h0080151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Price R. Primary prevention of secondary disorders: A proposal and agenda. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1993;21:607–617. doi: 10.1007/BF00942174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R, Ustun T. The world mental health (WMH) survey initiative version of the world health organization (WHO) composite international diagnostic interview (CIDI) International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2004;13:93–121. doi: 10.1002/mpr.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirisci L, Mezzich A, Tarter R. Norms and sensitivity of the adolescent version of the drug use screening inventory. Addictive Behaviors. 1995;20:149–157. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(94)00058-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolko DJ, Loar LL, Sturnick D. Inpatient social cognitive skills training groups with conduct disordered and attention deficit disordered children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines. 1990;31:737–748. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1990.tb00814.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Last CG, Hansen C, Franco N. Anxious children in adulthood: A prospective study of adjustment. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36(5):645–652. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199705000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leon AC, Olfson M, Portera L, Farber L, Sheehan DV. Assessing psychiatric impairment in primary care with the Sheehan Disability Scale. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine. 1997;27:93–105. doi: 10.2190/T8EM-C8YH-373N-1UWD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leon AC, Shear MK, Portera L, Klerman GL. Assessing impairment in patients with panic disorder: The Sheehan Disability Scale. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 1992;27:78–82. doi: 10.1007/BF00788510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez B, Turner R, Saavedra L. Anxiety and risk for substance dependence among late adolescents/young adults. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2005;19:275–294. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2004.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, Mehta RL, Molnar BE, Walters EE, Swendsen JD, Aguilar-Gaziola S, et al. Comorbidity of substance use disorders with mood and anxiety disorders: Results of the international consortium in psychiatric epidemiology. Addictive Behaviors. 1998;23:893–907. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(98)00076-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nevo GA, Manassis K. Outcomes for treated anxious children: A critical review of long-term follow-up studies. Depression and Anxiety. 2009;26:650–660. doi: 10.1002/da.20584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ollendick TH, King NJ. Empirically supported treatments for children with phobic and anxiety disorders. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1998;27:156–167. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2702_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ollendick TH, King NJ. Evidence-based treatments for children and adolescents: Issues and commentary. In: Kendall PC, editor. Child and adolescent therapy. 4. New York: Guilford Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ost LG. Age of onset of different phobias. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1987;96:223–229. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.96.3.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pine D, Cohen P, Gurley D, Brook J, Ma Y. Risk for early-adulthood anxiety and depressive disorders in adolescents with anxiety and depressive disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1998;55:56–64. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Placchi M. Measuring disability in subjects with anxiety disorders. European Psychiatry. 1997;12(Suppl):249–253. doi: 10.1016/S0924-9338(97)89092-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins L, Wing J, Wittchen H, Helzer J, Babor T, Burke J, et al. The composite international diagnostic interview: An epidemiologic instrument suitable for use in conjunction with different diagnostic systems and in different cultures. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1988;45:1069–1077. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800360017003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin HC, Rapaport MH, Levine B, Gladsjo JK, Rabin A, Auerbach M, et al. Quality of well being in panic disorder: The assessment of psychiatric and general disability. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2000;57:217–221. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(99)00030-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudd D, Joiner T, Rumzek H. Childhood diagnoses and later risk for multiple suicide attempts. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2004;34:113–125. doi: 10.1521/suli.34.2.113.32784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan D. The diagnosis and drug treatment of anxiety disorders. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry. 1983;7:599–603. doi: 10.1016/0278-5846(83)90031-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan D, Sheehan K, Minichiello W. Age of onset of phobic disorders: A reevaluation. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 1981;22:544–553. doi: 10.1016/0010-440x(81)90002-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman W, Pina AA, Viswesvaran C. Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for phobic and anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2008;37:105–130. doi: 10.1080/15374410701817907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storch EA, Roberti JW, Roth DA. Factor structure, concurrent validity, and internal consistency of the Beck Depression Inventory-Second edition in a sample of college students. Depression and Anxiety. 2004;19:187–189. doi: 10.1002/da.20002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss CC, Lease C, Last C, Francis G. Overanxious disorder: An examination of developmental differences. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1988;11:433–443. doi: 10.1007/BF00914173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarter R. Evaluation and treatment of adolescent substance abuse: A decision tree method. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 1990;16:1–46. doi: 10.3109/00952999009001570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toumbourou JW, Stockwell T, Neighbors C, Marlatt GA, Sturge J, Rehm J. Interventions to reduce harm associated with adolescent substance use. Lancet. 2007;369:1391–1401. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60369-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walkup J, Albano AM, Piacentini J, Birmaher B, Compton S, Kendall PC. Cognitive-behavioral therapy, sertraline and their combination for children and adolescents with anxiety disorders: Acute phase efficacy and safety: The Child/Adolescent Anxiety Multimodal Study (CAMS) New England Journal of Medicine. 2008;359:2753–2766. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weeks JW, Heimberg RG. Evaluation of the psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory in a non-elderly adult sample of patients with generalized anxiety disorder. Depression and Anxiety. 2005;22:41–44. doi: 10.1002/da.20068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. International Classification of Diseases. 10. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1992. Revision (ICD-10) [Google Scholar]