Abstract

A retro-inverso, TAT-like peptide wherein lysine residues are replaced with cysteine residues bearing a disulfide-linked cysteamine group is found to engage in thiol–disulfide exchange with cysteine. These peptides are transported into cells and localize to lysosomes. Cellular uptake is enhanced in peptides bearing two cysteamine groups over those with one or none, by factors of approximately 1.5 and 12, respectively.

Keywords: Drug delivery, TAT peptide, Thiol–disulfide exchange, Cysteamine, Cystinosis, Cell uptake, Rare diseases

Cystinosis, a lysosomal storage disorder resulting from a defective cystine transporter, offers a compelling model for drug delivery vehicles. Cystinosis results from the accumulation of cystine (cysteine disulfide) in lysosomes after proteolysis because of failed lysosomal transport.1-5 This accumulation leads to intracellular crystallization and oftentimes, renal failure.6 Cystinosis is usually treated with large doses of cysteamine, 2-aminoethanethiol. Upon disulfide bond formation with cysteine, the cysteine–cysteamine molecule acts as a lysine isostere. This mimic can be effectively transported out of lysosomes by a lysine transporter.

Treatment of cystinosis with cysteamine bitartrate (Cystagon™) was approved by the FDA in 1994 and significantly increases life expectancy by retarding the onset of thyroid and renal failure.7,8 Cysteamine therapy, however, has limitations. Side effects of the drug include nausea and vomiting, difficulty in walking, and odor. Pediatric resistance to oral therapy has led to the investigation of other strategies for drug delivery including catheterization, enzyme replacement therapy, and cell transplantation.9-11 This situation has also inspired the design of new pro-drugs including phosphocysteamine,12 amino acid derivatives of cysteamine or cystamine,13 and lipophilic derivatives of cysteamine.14

Opportunities for enhancing treatment by facilitating delivery of this rapidly-cleared, charged small molecule might be realized by integrating the drug into a more bioavailable agent.15 Here we investigate cysteamine delivery to lysosomes using a TAT-like peptide (1), its ability to engage in thiol-disulfide exchange with cysteine, and its ability to translocate into cells when charged with cysteamine. This peptide and the analogues used in this study are shown in Chart 1.

Chart 1.

The TAT-like peptides described in this study. All amino acids of 1–5 are d-configuration. TMR is 5(6)-carboxytetramethylrhodamine. The designation ‘Ccyst’ refers to the cysteamine disulfide of cysteine. Isomers 3 and 4 are arbitrarily assigned.

The peptides described derive from the TAT-sequence16,17 and incorporate d-amino acids using the retro-inverso strategy18 to provide materials that should be less susceptible to proteolysis than the corresponding peptide comprising l-amino acids. Wender has shown that retro-inverso peptides gain entry to cells in a sequence-dependent manner.19 Two observations by Wender are exploited in the design. First, the retro-inverso TAT is more effectively transported than the natural analog. Second, lysine residues which are replaced here with cysteine–cysteamine disulfides appear to be the least important for effective trafficking.

To obtain the peptides, solid phase peptide synthesis was executed on using Fmoc-protected d-amino acids. Side chain protecting groups included t-butyl (Tyr), trityl (Gln and Cys), and 2,2,4,6,7-pentamethyldihydrobenzofuran-5-sulfonyl (Arg). Upon cleavage from the resin and isolation, the crude peptide was reacted with 2-(2-pyridyditho)ethylamine to provide peptide (1) charged with two cysteamine groups. The resulting product was purified by HPLC and characterized by 1D and 2D NMR spectroscopy and mass spectrometry. Installation of a fluorescent dye, 5(6)-carboxytetramethylrhodamine (TMR) was accomplished on solid phase. The TMR-labeled peptides were cleaved from the resin, isolated, and reacted with the pyridylthio-activated cysteamine to provide the desired peptide bearing two cysteamine molecules (2) and the side products bearing one cysteamine molecule (3 and 4 as isomers arbitrarily assigned), and no cysteamine molecules (5), respectively. HPLC and MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry was used to identify these products.

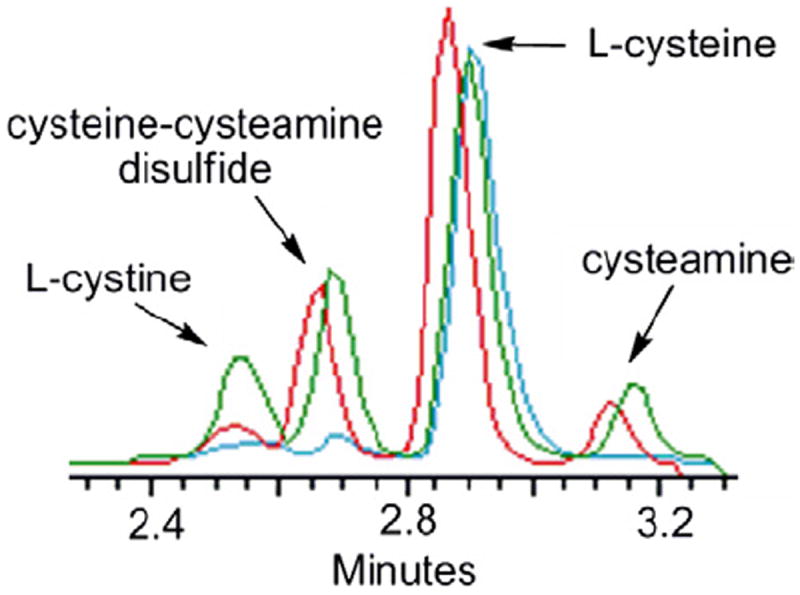

In order to investigate the thiol–disulfide exchange reaction, peptide 1 (at 0.36 mM) was incubated in 1 mM l-cysteine solution (aq). The reaction was analyzed by HPLC at 30 min, 6 h, and 24 h, respectively. As shown in Figure 1, cystine (the Cys-Cys disulfide) and a cysteine–cysteamine complex begin to appear after 30 min of reaction (blue trace). The level of a cysteine–cysteamine complex, the critical product, was significantly higher than that of cystine at 6 h (red trace). The release of cysteamine is also observed in the reaction. Peptide 1 yielded a peptide with an intramolecular disulfide bond as the major product which eluted uniquely at 26.6 min by HPLC and was confirmed by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. The results encouragingly show that the peptide carrying cysteamine can productively engage in thiol–disulfide exchange to provide the desired mixed disulfide cysteine–cysteamine intermediate. The equilibrium between 1 and free cysteine is complex with many species readily formulated hypothetically. In addition to 1 and its two isomeric single thiol/single cysteamine adducts, its fully reduced form, and its intra-disulfide form, cysteine can exchange to form an additional five adducts. Indeed, following the course of the equilibrium reaction between peptide and cysteine by HPLC reveals a rich diversity of compounds which will be pursued in future studies.

Figure 1.

HPLC traces of a thiol–disulfide exchange reaction of peptide 1 in 1 mM cysteine (aq) after 30 min (blue line), 6 h (red line), and 24 h (green line), respectively.

For this construct to productively participate in drug delivery, cellular uptake is critical. We examined the ability of these peptides to enter cells using fluorescence microscopy. Compound 2 (1 μM) was incubated for 1 h with cells transiently expressing Lamp-1 Cerulean, a blue fluorescent protein marker of late endosomes and lysosomes. The cells were then washed and incubated in fresh media for two additional hours for the compound to accumulate in lysosomes. Figure 2 shows a clear colocalization between the TMR label and lysosomes as expected.20

Figure 2.

Confocal fluorescence images of a representative HeLa cell expressing Cerulean Lamp-1 (pseudocolored green) after treatment with compound 2 (pseudocolored red). Colocalization of 2 and late endosomes/lysosomes is illustrated by the presence of the yellow color in the red/green overlay image.

Incubation of cells with 2–4 and 5 show an interesting trend (Fig. 3). Of the peptides, peptide 2 is endocytosed at the highest level. The partly reduced peptides 3 and 4 shows markedly less uptake, and little uptake is seen for the full reduced molecule, 5.

Figure 3.

Average fluorescence intensity of 50 cells incubated with the TAT-like peptides.

The drug delivery strategy proposed is designed to take advantage of the equilibrium resulting from thiol–disulfide exchange. Physiological conditions and disease state productively reinforce this design and may offer an opportunity to use peptides like 1 in a catalytic role. For this peptide to be a therapeutic phase transfer catalyst, it must enter cells, release cysteamine, be excreted, be recharged with cysteamine, and be recycled. These elements will be explored and reported in due course.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The NIH (EES R01 NIGMS 64560) is thanked for support. Dr. Bruce Barshop is thanked for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.07.046.

References and notes

- 1.Schneider JA, Schulman JD. Metabolism. 1977;26:817. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(77)90070-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nesterova G, Gahl W. Pediatr Nephrol. 2008;23:863. doi: 10.1007/s00467-007-0650-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ruivo R, Anne C, Sagné C, Gasnier B. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1793:636. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thoene JG. Mol Gen Metab. 2007;92:292. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2007.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Emadi A, Burns KH, Confer B, Borowitz MJ, Streiff MB. Acta Haematol. 2008;119:169. doi: 10.1159/000134222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gahl WA, Thoene JG, Schneider JAN. Engl J Med. 2002;347:111. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra020552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fidler MC, Barshop BA, Gangoiti JA, Deutsch R, Martin M, Schneider JA, Dohil R. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;63:36. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2006.02734.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schneider JA, Clark KF, Greene AA, Reisch JS, Markello TC, Gahl WA, Thoene JG, Noonan PK, Berry KA. J Inherit Metab Dis. 1995;18:387. doi: 10.1007/BF00710051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pastores GM, Barnett NL. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs. 2005;10:891. doi: 10.1517/14728214.10.4.891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stöllberger C, Finsterer J. Clin Cardiol. 2007;30:375. doi: 10.1002/clc.20005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kleta R, Gahl WA. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2004;5:2255. doi: 10.1517/14656566.5.11.2255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smolin LA, Clark KF, Thoene JG, Gahl WA, Schneider JA. Pediatr Res. 1988;23:616. doi: 10.1203/00006450-198806000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anderson RJ, Cairns D, Cardwell WA, Case M, Groundwater PW, Hall AG, Hogarth L, Jones AL, Meth-Cohn O, Suryadevara P, Tindall A, Thoene JG. Lett Drug Des Discovery. 2006;3:336. [Google Scholar]

- 14.McCaughan B, Kay G, Knott RM, Cairns D. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2008;18:1716. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.01.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wadouachi A, Boutbaiba-Stasik I, Demailly G, Uzan R, Beaupere D. Nat Prod Lett. 1993;2:277. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Green M, Loewenstein PM. Cell. 1988;55:1179. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90262-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang X, Huq I, Rana TM. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:6444. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fisher PM. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2003;4:339. doi: 10.2174/1389203033487054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wender PA, Mitchell DJ, Pattabiraman K, Pelkey ET, Steinman L, Rothbard JB. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:13003. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.24.13003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Duchardt F, Fotin-Mleczek M, Schwarz H, Fischer R, Brock R. Traffic. 2007;8:848. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2007.00572.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.