Abstract

Background

Although associations between personality disorders and psychiatric disorders are well established in general population studies, their association with liability dimensions for externalizing and internalizing disorders has not been fully assessed. The purpose of this study is to examine associations between personality disorders (PDs) and lifetime externalizing and internalizing Axis I disorders.

Methods

Data were obtained from the total sample of 34,653 respondents from Wave 2 of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC). Drawing on the literature, a 3-factor exploratory structural equation model was selected to simultaneously assess the measurement relations among DSM-IV Axis I substance use and mood and anxiety disorders and the structural relations between the latent internalizing-externalizing dimensions and DSM-IV PDs, adjusting for gender, age, race/ethnicity, and marital status.

Results

Antisocial, histrionic, and borderline PDs were strong predictors for the externalizing factor, while schizotypal, borderline, avoidant, and obsessive-compulsive PDs had significantly larger effects on the internalizing fear factor when compared to the internalizing misery factor. Paranoid, schizoid, narcissistic, and dependent PDs provided limited discrimination between and among the three factors. An overarching latent factor representing general personality dysfunction was significantly greater on the internalizing fear factor followed by the externalizing factor, and weakest for the internalizing misery factor.

Conclusion

Personality disorders offer important opportunities for studies on the externalizing-internalizing spectrum of common psychiatric disorders. Future studies based on panic, anxiety, and depressive symptoms may elucidate PD associations with the internalizing spectrum of disorders.

Keywords: DSM-IV personality disorders; DSM-IV substance use, mood, and anxiety disorders; epidemiology; structural equation modeling

1. Introduction

The National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) has provided extensive information for all 10 DSM-IV PDs in the general population (Grant et al., 2004a, 2004b, 2005b, 2005c; Pulay et al., 2009). Confirmatory 1-factor analyses of symptom criteria for each NESARC PD provided an excellent fit with the data (CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.99; RMSEA < 0.02) (Harford et al., 2012). Studies using clinical and community samples have examined the underlying structure and organization of DSM-IV PDs, but the findings have been inconsistent; supporting models include 2 to 10 factors (Fossati et al., 2000; Huprich et al., 2010; Nestadt et al., 2006). In a recent analysis with the NESARC, Trull and colleagues (2012) extracted six DSM-IV PD factors (paranoid, avoidant/dependent, antisocial, schizoid, narcissistic, and obsessive-compulsive) and a seventh factor based on symptoms from borderline, schizotypal, and narcissistic PDs. Another NESARC study provided support for the DSM-IV hierarchical model for the PD cluster organization (A, odd/eccentric; B, dramatic/emotional; C, anxious/fearful) in which the 3 lower-order clusters form a higher-order factor (Cox et al., 2012; Jahng et al., 2011), although other exploratory models with 3-factor solutions often do not match the DSM clusters of PDs (Dowson and Berrios, 1991; Blackburn et al., 2005). The presence of high intercorrelations between DSM-IV personality disorders (Grant et al., 2005c; McGlashan et al., 2000; Stuart et al., 1998; Zimmerman et al., 2005) nevertheless suggests that each of these disorders may be alternative manifestations of a single underlying process.

Recent conceptualizations, based on nationally representative samples, have proposed that psychiatric disorders are best understood along broad dimensions of externalization and internalization. Factor analytic studies have identified a 3-factor model that includes one externalizing factor represented by antisocial personality disorder (ASPD) and substance use dependence and two correlated internalizing factors labeled “distress” (major depression, dysthymia, and generalized anxiety) and “fear” (social phobia, specific phobia, and panic with and without agoraphobia). Studies have indicated overall consistency with these dimensions, despite some variation according to diagnosis and age composition of samples (Beesdo-Baum et al., 2009; Cox et al., 2002; Farmer et al., 2009; Kendler et al., 2003; Krueger et al., 1998, 2005; Markon and Krueger, 2005; Vollebergh et al., 2001).

The conceptualization of the underlying liability dimensions of psychiatric disorders has mainly focused on common Axis I disorders, but recent studies have expand these dimensions to include other less common disorders and Axis II personality disorders (Kendler et al, 2011; Kotov et al, 2011; Keyes et al, 2012; Markon, 2010; Roysambe et al, 2011). These studies provide support for externalizing and internalizing liability, though some studies found separate but moderately correlated externalizing and internalizing factors for Axis I and Axis II disorders (Kendler et al., 2011; Roysambe et al., 2011).

Drawing on the NESARC, the major objective of the present study is to explore the relationships between the full set of DSM-IV PDs and the externalizing-internalizing structure of common mental disorders. Based on extensive associations between ASPD and substance dependence, ASPD has been considered endogenous and included with externalizing disorders (Krueger et al., 2005; Markon and Krueger, 2005). Therefore, the present study considers the same model specification that groups ASPD with substance use disorders as indicators of the externalizing dimension and examines associations with the other 9 PDs. In addition, the present study includes an alternative model specification with ASPD as an exogenous predictor with all other PDs. As a sensitivity analysis, the model is further examined using the alternative coding of PD symptoms that Trull and colleagues (2010) have proposed. The alternative coding of symptoms requires each symptom criterion to be associated with social and/or occupational dysfunction. These proposed diagnostic rules yield lower prevalence rates of PDs that are more similar to those obtained in other national surveys (Coid et al., 2006; Lenzenweger et al., 2007) and have been adopted in other NESARC studies (Jahng et al., 2011; Trull et al., 2012). In light of the current debate about the latent PD structure, this study further assesses the association between a general personality dysfunction factor and externalizing-internalizing disorders. Finally, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) of both the PDs and the Axis I disorders was conducted to test the robustness of ESEM results.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

The NESARC Wave 1 is a national survey of the U.S. civilian population, based on a group quarters sampling frame as described in detail elsewhere (Grant et al., 2001b). Face-to-face interviews were conducted with 43,093 respondents in 2001–2002. The overall response rate was 81%. Blacks, Hispanics and young adults ages 18 to 24 were oversampled in the NESARC. Weights were provided in NESARC to account for oversampling, nonresponse, and the selection of one person per household. The weighted data were representative of the civilian noninstitutional population of the United States based on the 2000 Decennial Census. All eligible respondents from Wave 1 who had not died, were not institutionalized, had not left the country, or had not entered the military were reinterviewed approximately 3 years later (n=39,959). The reinterview completion rate was 86.9%, yielding a total of 34,653 adults. Sample weights for Wave 2 respondents were calculated to ensure that the weighted Wave 2 sample represented the original baseline population of 2001–2002. The present analysis draws on the total sample of 34,653 respondents. Details about the NESARC sampling design and methodology are described elsewhere (Grant et al., 2004b, 2009).

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Personality Disorders

Seven PDs were assessed in the Wave 1 NESARC (paranoid, schizoid, histrionic, antisocial, avoidant, dependent, and obsessive-compulsive PDs) (Grant et al., 2004a). Borderline, schizotypal, and narcissistic PDs were assessed in the Wave 2 NESARC (Grant et al., 2008; Pulay et al., 2009; Stinson et al., 2008). All variables in the present study, with the exception of 7 PDs from Wave 1, were obtained from the 2004–2005 Wave 2 follow-up survey.

The assessments of PDs were based on the Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-DSM-IV (AUDADIS-IV) (Grant et al., 2001a; Ruan et al., 2008). The diagnosis of each PD, except ASPD, required an evaluation of the individual’s long-term pattern of functioning (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). Respondents were asked a series of PD symptom questions about how they felt or acted most of the time throughout their lives, regardless of the situation or whom they were with. They were instructed not to include symptoms limited to times when they were depressed, manic, drinking heavily, using medicines or drugs, or experiencing withdrawal symptoms, or during times when they were physically ill. To receive a DSM-IV PD diagnosis, respondents needed to endorse the requisite number of DSM-IV symptom items for the particular PD, and at least one positive symptom must have caused social and/or occupational dysfunction. The DSM-IV distress/impairment criterion does not apply to ASPD. Multiple symptom items were used to operationalize the more complex criteria associated with certain PDs. Consistent with DSM-IV, diagnoses of ASPD required the requisite number of criteria, in addition to the specified number of criteria for conduct disorder before age 15. Reliability and validity of AUDADIS-IV personality disorders have been reported elsewhere (Grant et al., 2003; Ruan et al., 2008).

2.2.2. Substance Use Disorders (SUD)

Wave 2 lifetime diagnoses of DSM-IV alcohol and drug abuse and dependence and nicotine dependence were included in the analyses. Nicotine dependence was assessed for any tobacco product. DSM-IV drug-specific abuse and dependence diagnoses are aggregated into any drug abuse and any drug dependence diagnoses for analysis. Reliability and validity of substance use disorders were good to excellent as reported elsewhere (Grant et al., 1995; Hasin et al., 1997).

2.2.3. Mood and Anxiety Disorders

Wave 2 DSM-IV lifetime mood disorders included major depression and dysthymia. Anxiety disorders included panic disorder (with and without agoraphobia), social and specific phobias, and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD). AUDADIS-IV methods to diagnose these disorders are described in detail elsewhere (Hasin et al., 2005; Grant et al., 2005b; Stinson et al., 2007). All AUDADIS-IV mood and anxiety disorder diagnoses excluded disorders that were substance induced or due to general medical conditions. Reliability and validity of mood and anxiety diagnoses were fair to excellent and have been reported elsewhere (Grant et al., 2004a, 2005a, 2005b).

2.2.4. Other Covariates

Demographic variables included male gender, age (in years), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaskan Native, non-Hispanic Asian/Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, Hispanic of any races, with non-Hispanic White as referent), and marital status (never married, previously married, with married as referent).

2.3. Analytic Plan

The analysis uses a newly developed method for exploratory structural equation modeling (ESEM), which integrates exploratory factor analysis (EFA) into structural equation modeling such that factor indicators load on all factors, avoiding the requirement of zero cross loadings in CFA (Asparouhov and Muthén, 2009; Eaton et al., 2012; Marsh et al., 2009, 2010). We opted for EFA over CFA because in a strict CFA, the presence of zero cross-loading does not always yield a well-fitting model, and misspecification of zero loadings in factor identification may yield distorted factors with overestimated factor correlations and subsequent distorted structural relations. The ESEM model with covariates estimates both the measurement and structural parts simultaneously (Asparouhov and Muthén, 2009). Specifically, the lifetime Axis I mental disorders were included as manifest variables for the 3 latent factors presumed to represent one externalizing and two internalizing (i.e., fear and distress) dimensions in the ESEM, and PDs were included as covariates in the structural model together with gender, age, race/ethnicity, and marital status. However, to conserve space, specific demographic effects are not shown, as these associations have been well documented in other NESARC studies (Grant et al., 2004a).

The following ESEM models were conducted: (1) ASPD in the measurement part of the model, with the remaining 9 PDs and demographic covariates in the structural model; (2) All PDs including ASPD included in the structural model; (3) ASPD in the measurement part of the model, with alternative coding proposed by Trull and colleagues (2010); (4) a single latent variable for personality dysfunction defined by the 9 PDs in the structural model, with ASPD in the measurement model. Exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses were conducted in the preliminary assessment of the general personality dysfunction factor. Finally, a CFA of both the PDs and the Axis I disorders was conducted to test the robustness of ESEM results.

The estimator for analysis was a robust, weighted, least-squares estimator with a geomin rotation. Model fit indices included comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), and root mean square error approximation (RMSEA). The following cutoff values were used as indicators of good fit: CFI or TLI > 0.95; RMSEA < 0.06 (Bentler, 1990; Hu and Bentler, 1999). The analyses were conducted using the statistical modeling program Mplus (Muthén and Muthén, 1998-2010), which takes into account sampling stratification, clustering, and weights in ESEM and CFA models.

3. Results

3.1. Personality Disorder and Externalizing/Internalizing Disorders

The 3-factor ESEM model based on the 10 DSM-IV Axis I disorders and ASPD is shown in Table 1. The CFI and RMSEA indices indicate a generally good fit for the model (CFI = .97; TLI = .95, RMSEA = .01). Factor 1 (externalizing disorders) is well defined by ASPD and the three substance use disorders. Factor 2 (internalizing fear) is defined by panic with agoraphobia and social and specific phobia; factor 3 (internalizing misery) is defined by major depression and dysthymia. There are moderate cross-loadings on the two internalizing factors for panic without agoraphobia and for generalized anxiety. The residual covariation between the factors is as follows: factor 1 and factor 2 = 0.25 (99% CI = 0.20, 0.30); factor 1 and factor 3 = 0.30 (99% CI = 0.23, 0.37); and factor 2 and factor 3 = 0.32 (99% CI = 0.26, 0.39). The factors correlations are somewhat lower than those reported in other studies due to the inclusion of cross-loadings in the ESEM model.

Table 1.

Exploratory Structural Equation Model between Personality Disorders and Latent Dimensions of Externalizing and Internalizing Mental Disorders, Wave 2 NESARCa (n=34,653).

| Variables | Factor 1 (externalizing) |

Factor 2 (internalizing fear) |

Factor 3 (internalizing misery) |

|---|---|---|---|

| DSM-IV Disorders | Estimate (99% C.I.) | Estimate (99% C.I.) | Estimate (99% C.I.) |

| Measurement Model | |||

| Antisocial PD | 0.58* (0.53, 0.63) | 0.03 (−0.04, 0.10) | 0.01 (−0.05, 0.08) |

| Alcohol use disorders | 0.75* (0.72, 0.79) | −0.01 (−0.04, 0.01) | −0.03 (−0.07, 0.01) |

| Drug use disorders | 0.77* (0.73, 0.80) | −0.01 (−0.04, 0.02) | −0.01 (−0.04, 0.02) |

| Nicotine dependence | 0.55* (0.52, 0.58) | 0.08* (0.03, 0.12) | 0.02 (−0.02, 0.06) |

| Panic without agoraphobia | 0.12* (0.07, 0.16) | 0.24* (0.17, 0.30) | 0.23* (0.17, 0.30) |

| Panic with agoraphobia | 0.01 (−0.02, 0.03) | 0.83* (0.77, 0.90) | −0.11 (−0.21, −0.02) |

| Social phobia | −0.03 (−0.09, 0.03) | 0.68* (0.61, 0.74) | 0.04 (−0.03, 0.11) |

| Specific phobia | 0.02 (−0.03, 0.06) | 0.63* (0.58, 0.67) | −0.01 (−0.03, 0.02) |

| Generalized anxiety | −0.01 (−0.03, 0.03) | 0.40* (0.34, 0.46) | 0.37* (0.31, 0.43) |

| Major depression | 0.01 (−0.03, 0.04) | 0.03* (0.01, 0.05) | 0.82* (0.75, 0.89) |

| Dysthymia | 0.01 (−0.04, 0.03) | −0.05 (−0.13, 0.02) | 0.84* (0.76, 0.92) |

| Covariates | |||

| Lifetime Personality Disorder | Estimate (99% C.I.) | Estimate (99% C.I.) | Estimate (99% C.I.) |

| Paranoidb | 0.38* (0.25, 0.51) | 0.46* (0.32, 0.60) | 0.21* (0.07, 0.35) |

| Schizoidb | 0.31* (0.18, 0.45) | 0.53* (0.38, 0.68) | 0.37* (0.22, 0.51) |

| Schizotypalc | 0.15* (0.03, 0.27) | 0.64* (0.50, 0.77) | 0.13 (−0.20, 0.28) |

| Histrionicb | 0.48* (0.30, 0.65) | 0.23* (0.06, 0.40) | −0.21* (−0.42, −0.01) |

| Borderlinec | 0.66* (0.55, 0.76) | 0.73* (0.60, 0.85) | 0.48* (0.38, 0.59) |

| Narcissisticc | 0.19* (0.09, 0.29) | 0.15* (0.02, 0.27) | −0.02 (−0.13, 0.08) |

| Avoidantb | 0.04 (−0.10, 0.29) | 0.71* (0.53, 0.89) | 0.41* (0.24, 0.58) |

| Dependentb | 0.06 (−0.27, 0.40) | 0.33 (−0.04, 0.71) | −0.20 (−0.54, 0.15) |

| Obsessive-compulsiveb | 0.33* (0.23, 0.43) | 0.53* (0.43, 0.63) | 0.36* (0.25, 0.47) |

Adjusted for gender, age, race/ethnicity, and marital status.

Wave 1 assessment.

Wave 2 assessment.

p < .01; CFI = .97; TLI = .95; RMSEA = .01.

Adjusted for all other variables in the model (Table 1), the structural coefficients indicate that, compared with those without the specific PDs, individuals with paranoid, schizoid, schizotypal, histrionic, borderline, narcissistic, and obsessive-compulsive PDs have significantly higher estimates on factor 1 (externalizing disorders). All PDs with the exception of dependent PD have significantly greater effects on factor 2 (internalizing fear). Individuals with paranoid, schizoid, borderline, avoidant, and obsessive-compulsive PDs have significantly higher estimates on factor 3 (internalizing misery), but those with a histrionic PD have a significantly lower estimate.

Inspecting whether confidence intervals overlap or not shows that the regression coefficients of schizotypal, avoidant, and obsessive-compulsive PDs are significantly higher for factor 2 compared with factor 1, while the regression coefficients of schizotypal, histrionic, and borderline PDs are significantly higher for factor 2 compared with factor 3. The three latent factors are not differentiated by paranoid, schizoid, and dependent PDs, and dependent PD is not significantly associated with any factor.

In the second 3-factor ESEM model (CFI = .97; TLI = .95, RMSEA = .01), ASPD was not included as an indicator in the measurement part of the model but included as a covariate instead. As shown in Table 2, ASPD is significantly associated with the externalizing factor, and significantly higher than that of all other PDs. The association between schizotypal PD and the externalizing factor is no longer statistically significant with the inclusion of ASPD in the structural model, while the remaining PD regression coefficients are largely unchanged. The PD regression coefficients with respect to both internalizing factors are essentially unchanged for both models (Tables 1 and 2).

Table 2.

Exploratory Structural Equation Model between Personality Disorders and Latent Dimensions of Externalizing and Internalizing Mental Disorders (Antisocial PD in the Structural Model), Wave 2 NESARCa (n=34,653).

| Variables | Factor 1 (externalizing) |

Factor 2 (internalizing fear) |

Factor 3 (internalizing misery) |

|---|---|---|---|

| DSM-IV Axis I Disorders | Estimate (99% C.I.) | Estimate (99% C.I.) | Estimate (99% C.I.) |

| Measurement Model | |||

| Alcohol use disorders | 0.72* (0.68, 0.76) | −0.01 (−0.03, 0.02) | −0.01 (−0.04, 0.02) |

| Drug use disorders | 0.77* (0.73, 0.80) | −0.01 (−0.04, 0.02) | −0.01 (−0.04, 0.02) |

| Nicotine dependence | 0.53* (0.50, 0.56) | 0.08* (0.03, 0.13) | 0.03 (−0.01, 0.07) |

| Panic without agoraphobia | 0.11* (0.07, 0.15) | 0.24* (0.17, 0.30) | 0.24* (0.17, 0.30) |

| Panic with agoraphobia | 0.01 (−0.02, 0.03) | 0.83* (0.76, 0.90) | −0.11* (−0.21, −0.02) |

| Social phobia | −0.03 (−0.09, 0.02) | 0.68* (0.62, 0.74) | 0.04 (−0.03, 0.11) |

| Specific phobia | 0.01 (−0.03, 0.06) | 0.63* (0.58, 0.67) | −0.01 (−0.03, 0.02) |

| Generalized anxiety | −0.01 (−0.03, 0.02) | 0.40* (0.34, 0.46) | 0.37* (0.31, 0.43) |

| Major depression | 0.01 (−0.02, 0.05) | 0.03* (0.01, 0.05) | 0.82* (0.75, 0.88) |

| Dysthymia | −0.01 (−0.04, 0.03) | −0.05 (−0.12, 0.02) | 0.84* (0.76, 0.92) |

| Covariates | |||

| Lifetime Personality Disorder | Estimate (99% C.I.) | Estimate (99% C.I.) | Estimate (99% C.I.) |

| Paranoidb | 0.21* (0.06, 0.35) | 0.44* (0.30, 0.58) | 0.19* (0.05, 0.33) |

| Schizoidb | 0.22* (0.08, 0.36) | 0.51* (0.36, 0.66) | 0.36* (0.21, 0.50) |

| Schizotypalc | 0.06 (−0.07, 0.19) | 0.63* (0.49, 0.76) | 0.12 (−0.03, 0.27) |

| Histrionicb | 0.30* (0.12, 0.48) | 0.20* (0.03, 0.37) | −0.24* (−0.45, −0.04) |

| Antisocialb | 1.32* (1.18, 1.45) | 0.32* (0.16, 0.48) | 0.23* (0.09, 0.36) |

| Borderlinec | 0.67* (0.57, 0.78) | 0.72* (0.59, 0.85) | 0.48* (0.37, 0.58) |

| Narcissisticc | 0.17* (0.07, 0.27) | 0.14* (0.02, 0.26) | −0.03 (−0.13, 0.08) |

| Avoidantb | 0.04 (−0.14, 0.23) | 0.70* (0.52, 0.88) | 0.41* (0.23, 0.58) |

| Dependentb | −0.17 (−0.51, 0.17) | 0.30 (−0.08, 0.68) | −0.22 (−0.57, 0.13) |

| Obsessive-compulsiveb | 0.24* (0.14, 0.34) | 0.52* (0.42, 0.62) | 0.35* (0.24, 0.46) |

Adjusted for gender, age, race/ethnicity, and marital status.

Wave 1 assessment.

Wave 2 assessment.

p < .01; CFI = .97; TLI = .95; RMSEA = .01.

In the third 3-factor ESEM model (CFI = .97; TLI = .95, RMSEA = .01), ASPD was included as an indicator in the measurement part of the model, and the remaining PDs were included based on the alternative coding regarding social and/or occupational dysfunction proposed by Trull and colleagues (2010). Although these diagnostic rules yield lower prevalence rates of PDs, there are similarities with the estimates shown in Table 1. As shown in Table 3, the regression coefficients of avoidant and obsessive-compulsive PDs are significantly higher for factor 2 compared with factor 1. The regression coefficient of schizotypal PD is significant for factor 2 but not for factor 3, and the regression coefficient of borderline PD is significantly higher for factor 2 compared with factor 3. The alternative coding, however, yields some differences with the ESEM model in Table 1. The regression coefficients of paranoid and avoidant PDs are significantly related to each factor but no longer significant for the associations between schizoid PD and factors 1 and 3; schizotypal PD and factor 1; histrionic PD and factors 2 and 3; and narcissistic PD and factors 1 and 2.

Table 3.

Exploratory Structural Equation Model between Personality Disorders (Based on Alternative Coding Proposed by Trull et al., 2010),a and Latent Dimensions of Externalizing and Internalizing Mental Disorders, Wave 2 NESARCb (n=34,653).

| Variables | Factor 1 (externalizing) |

Factor 2 (internalizing fear) |

Factor 3 (internalizing misery) |

|---|---|---|---|

| DSM-IV Disorders | Estimate (99% C.I.) | Estimate (99% C.I.) | Estimate (99% C.I.) |

| Measurement Model | |||

| Antisocial PD | 0.64* (0.60, 0.69) | 0.01 (−0.05, 0.06) | −0.01 (−0.06, 0.06) |

| Alcohol use disorders | 0.74* (0.71, 0.78) | −0.02 (−0.07, 0.02) | −0.01 (−0.05, 0.02) |

| Drug use disorders | 0.79* (0.76, 0.82) | 0.01 (−0.03, 0.03) | −0.01 (−0.05, 0.03) |

| Nicotine dependence | 0.54* (0.51, 0.59) | 0.09* (0.03, 0.13) | 0.03 (−0.01, 0.08) |

| Panic without agoraphobia | 0.12* (0.07, 0.16) | 0.26* (0.19, 0.32) | 0.23* (0.17, 0.29) |

| Panic with agoraphobia | 0.01 (−0.02, 0.03) | 0.83* (0.77, 0.90) | −0.12 (−0.21, −0.02) |

| Social phobia | 0.03 (−0.08, 0.03) | 0.69* (0.63, 0.75) | 0.04 (−0.03, 0.11) |

| Specific phobia | 0.01 (−0.04, 0.05) | 0.61* (0.58, 0.70) | −0.01 (−0.03, 0.01) |

| Generalized anxiety | 0.01 (−0.02, 0.03) | 0.43* (0.38, 0.49) | 0.35* (0.29, 0.41) |

| Major depression | −0.01 (−0.04, 0.02) | 0.01 (−0.02, 0.05) | 0.86* (0.78, 0.94) |

| Dysthymia | −0.01 (−0.04, 0.04) | −0.02 (−0.07, 0.03) | 0.80* (0.73, 0.88) |

| Covariates | |||

| Lifetime Personality Disorder | Estimate (99% C.I.) | Estimate (99% C.I.) | Estimate (99% C.I.) |

| Paranoidc | 0.61* (0.43, 0.79) | 0.99* (0.82, 1.16) | 0.31* (0.11, 0.51) |

| Schizoidc | 0.26 (−0.02, 0.55) | 0.30* (0.03, 0.57) | 0.10 (−0.22, 0.42) |

| Schizotypald | −0.01 (−0.03, 0.28) | 0.43* (0.15, 0.70) | 0.07 (−0.23, 0.36) |

| Histrionicc | 0.54* (0.15, 0.93) | −0.13 (−0.61, 0.34) | 0.10 (−0.37, 0.57) |

| Borderlined | 0.96* (0.81, 1.11) | 1.19* (1.02, 1.36) | 0.52* (0.36, 0.67) |

| Narcissisticd | 0.13 (−0.08, 0.33) | 0.20 (−0.07, 0.47) | 0.02 (0.24, 0.27) |

| Avoidantc | 0.31* (0.07, 0.56) | 1.10* (0.85, 1.34) | 0.46* (0.21, 0.71) |

| Dependentc | −0.17 (−0.61, 0.27) | −0.04 (−0.51, 0.42) | −0.29 (−0.74, 0.17) |

| Obsessive-compulsivec | 0.26* (0.07, 0.44) | 0.64* (0.48, 0.80) | 0.38* (0.19, 0.57) |

Each PD symptom criterion is qualified by the presence of associated social and/or occupational dysfunction.

Adjusted for gender, age, race/ethnicity, and marital status.

Wave 1 assessment.

Wave 2 assessment.

p < .01; CFI = .97; TLI = .95; RMSEA = .01.

3.2. General Personality Disorder Factor as Indicator for Externalizing Disorders

The EFA of PDs using geomin and oblique rotated loadings indicated a better solution for 2 factors (CFI=0.99; TLI= 0.98; RMSEA=0.015) than for a single factor (CFI=0.92; TLI= 0.90; RMSEA=0.04). The minor second factor included the three PDs from Wave 2, and the factors were highly correlated (r = 0.63). The CFA with a single factor, adjusting for the residual correlates for the Wave 2 PDs, yielded a good fit (CFI=0.99; TLI= 0.99; RMSEA=0.014).

Preliminary analyses included independent, factor-specific CFAs indicated that the regression coefficient of the general PD factor was highest for internalizing fear (0.83, 99% CI = 0.67, 0.99); followed by externalizing (0.41, 99% CI = 0.34, 0.49) and lowest for internalizing distress (0.24, 99% CI = 0.20, 0.29).

As shown in Table 4, the regression coefficient of the general PD factor was highest for internalizing fear (1.62, 99% CI = 1.40, 1.84), next highest for the externalizing factor (0.68, 99% CI = 0.58, 0.77), and lowest for the misery factor (0.37, 99% CI = 0.29, 0.44). Similar results (full ESEM model not shown) were found using the alternative coding regarding dysfunction proposed by Trull and colleagues (2010). The general PD factor was highest for internalizing fear (0.46, 99% CI = 0.41, 0.50), next highest for the externalizing factor (0.28, 99% CI = 0.25, 0.32), and lowest for the misery factor (0.14, 99% CI = 0.09, 0.19).

Table 4.

Exploratory Structural Equation Model between Latent Personality Disorders Factor and Latent Dimensions of Externalizing and Internalizing Mental Disorders. Wave 2 NESARCa (n=34,653).

| Variables | Factor 1 (externalizing) |

Factor 2 (internalizing fear) |

Factor 3 (internalizing misery) |

|---|---|---|---|

| DSM-IV Disorders | Estimate (99% C.I.) | Estimate (99% C.I.) | Estimate (99% C.I.) |

| Measurement Model | |||

| Antisocial PD | 0.73* (0.64, 0.82) | 0.16* (0.10, 0.22) | −0.12* (−0.22, −0.01) |

| Alcohol use disorders | 1.23* (1.09, 1.36) | −0.18* (−0.25, −0.11) | −0.001 (−0.002, −0.003) |

| Drug use disorders | 0.98* (0.90, 1.06) | −0.01 (−0.03, 0.01) | 0.04 (−0.03, 0.12) |

| Nicotine dependence | 0.54* (0.50, 0.58) | 0.03 (−0.01, 0.06) | 0.08* (0.03, 0.13) |

| Panic without agoraphobia |

0.10* (0.05, 0.14) | 0.20* (0.16, 0.25) | 0.26* (0.20, 0.33) |

| Panic with agoraphobia | −0.01 (−0.06, 0.04) | 0.79* (0.63, 0.96) | −0.08 (−0.24, 0.08) |

| Social phobia | 0.04 (−0.02, 0.11) | 0.66* (0.55, 0.76) | 0.02 (−0.02, 0.05) |

| Specific phobia | 0.04 (−0.01, 0.09) | 0.38* (0.32, 0.44) | 0.06 (−0.01, 0.12) |

| Generalized anxiety | −0.01 (−0.05, 0.03) | 0.49* (0.41, 0.57) | 0.46* (0.37, 0.55) |

| Major depression | 0.01 (−0.04, 0.04) | −0.01 (−0.03, 0.01) | 1.75* (1.13, 2.37) |

| Dysthymia | −0.01 (−0.05, 0.05) | 0.08 (−0.01, 0.16) | 1.14* (0.90, 1.38) |

| Covariates | |||

| Lifetime Personality Disorder Factor |

Estimate (99% C.I.) | Estimate (99% C.I.) | Estimate (99% C.I.) |

| Latent PD Factor | 0.68* (0.58, 0.77) | 1.62* (1.40, 1.84) | 0.37* (0.29, 0.44) |

Adjusted for gender, age, race/ethnicity, and marital status.

p < .01; CFI = .96; TLI = .95; RMSEA = .01.

3.3. Personality Disorder as Indicators of Externalizing/Internalizing Disorders

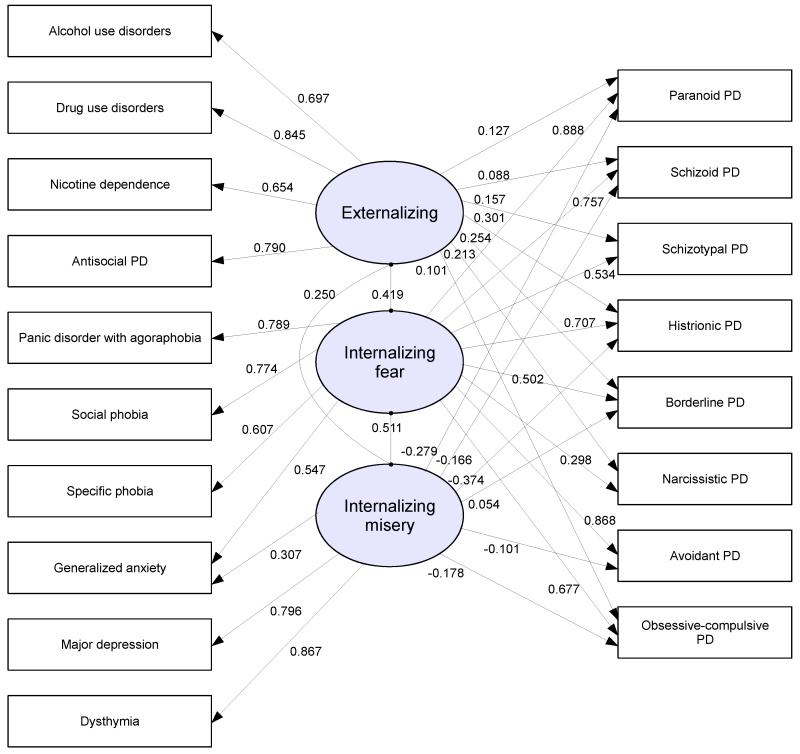

Based on the ESEM, all of the PDs and common psychiatric disorders were included in a CFA. Because the PDs were assessed in different waves, it was necessary to adjust for correlated errors for PDs assessed at wave 2. We also retained the cross-loading for generalized anxiety for the two internalizing factors. The CFA modeling for the combined set of Axis I and Axis II disorders fit the data well (CFI = .97; TLI = .96, RMSEA = .02) and the standardized estimates are shown in the Figure 1 (unstandardized estimates provided in supplemental material). Similar to the ESEM model, factor 2 (internalizing fear) is well defined by the majority of PDs and DSM-IV anxiety disorders, while several PDs have negative associations with factor 3 (internalizing distress). DSM-IV Cluster B PDs are significantly related to externalizing disorders (factor 1).

Figure 1.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis Using Personality Disorders and Substance Use and Mood and Anxiety Disorders as Indicators of Latent Dimensions of Externalizing and Internalizing Disorders, Wave 2 NESARC (n=34,653).

CFI = .97; TLI = .96; RMSEA = .02.

4. Discussion

This study has examined relationships between the full set of DSM-IV PDs and the externalizing-internalizing structure of common mental disorders. The factor structure for common mental disorders was comparable to those reported in the literature (Kendler et al., 2003; Krueger et al., 1998, 2005). However, the present study supported the externalizing-internalizing structure as three distinct dimensions, as did Beesdo-Baum and colleagues (2009).

A number of our findings, notably the strong association between ASPD and other Axis I externalizing disorders, also are consistent with the literature. As with the study by Jahng and colleagues (2011), our study further indicates significant associations between the externalizing factor and other Cluster B PDs (i.e., histrionic, borderline, and narcissistic PDs), though the association is significantly weaker for narcissistic relative to the other Cluster B PDs. The associations with the externalizing-internalizing factors among PDs other than ASPD are similar across models whether or not ASPD is an indicator of the externalizing factor. While there are significant factor loadings for Cluster B PDs on the externalizing factor in the CFA (Figure 1) for the combined Axis I disorders and PDs, they are significantly lower when compared to ASPD. The factor loadings for internalizing fear, however, are substantially higher for paranoid, schizoid, histrionic, avoidant, and obsessive-compulsive PDs and moderately high for schizotypal, borderline, and narcissistic PDs.

Overall, there was limited discrimination between specific PDs and the externalizing-internalizing structure. Schizotypal and avoidant PDs had distinct associations with factor 2 (fear) and, in concert with borderline PD, provided a strong contrast between the two internalizing factors, while schizotypal, avoidant, and obsessive-compulsive PDs further defined boundaries between factor 2 (fear) and factor 1 (externalizing disorders). More typically, the majority of PDs evidenced significant associations with all three factors, a finding consistent with multiple factor associations reported in other recent studies (Eaton et al., 2011; Kotov et al., 2011).

The presence of multidimensionality in PDs can pose problems in interpretation. PD symptom criteria include both externalizing and internalizing features, despite that individual PDs may have different relationships with these liability dimensions. Within the externalizing-internalizing framework, PD symptom criteria reflecting impulsivity, disinhibition, anger, or antagonism may relate to externalizing, while negative emotionality or affective instability may relate to internalizing. The exact nature of the relationship between the PDs and fear is not clear. Negative affect and emotional regulation are important features among PDs, but there may be important distinctions when related to externalizing and internalizing disorders. It is noteworthy that the two internalizing factors may be distinguished in terms of avoidance of social situations and/or specific objects compared with depressed mood or loss of interest or pleasure. PD negative emotions, for example, may have greater levels of arousal, or may be more readily activated with respect to perceived environmental threat when compared to more dampening (inhibited) effects associated with stress. More detailed analyses based on symptom criteria may help explicate the underlying structure of these disorders. Analysis of PD symptom criteria, however, is limited because each NESARC PD criterion is measured by a single item (2 or more items in a few cases), which affects reliability. A more promising approach could analyze associations between PDs and panic, anxiety, and depressive symptoms of these psychiatric disorders.

Findings from the present study further indicated that an overarching latent factor representing general personality dysfunction provided strong discrimination between the externalizing and internalizing factors, particularly the internalizing fear factor. The presence of multidimensionality in PDs associations and the need for hierarchical modeling of PDs (Cox et al., 2012; Jahng et al., 2011) may pose a challenge for proposals to relocate DSM-IV PDs with Axis I disorders in the forthcoming DSM-5, but the problem might be averted with the use of psychiatric symptoms (Markon, 2010) or personality traits (Krueger and Eaton, 2010).

While findings based on the alternative coding regarding dysfunction proposed by (Trull et al., 2010) were similar to those based on the NESARC coding, especially pertaining to the general PD factor, the lower prevalence of schizoid, schizotypal, histrionic, and dependent PDs (< 0.6%) may have affected estimates for individual PDs. Categorical models of PD dominate the current DSM-IV diagnostic system, but others have questioned whether PD symptom criteria provide coherent specific categories or are best viewed as indictors of more continuous dimensions (Krueger et al., 2005). Future studies based on the number of specific PD symptom criteria may be more efficient with respect to both reliability and PD severity.

Comparisons of our CFA with other similar studies of combined Axis I and II disorders (Kendler et al., 2011; Kotov et al., 2011; Markon, 2010; Roysamb et al., 2011) are constrained by variations in samples populations, disorder assessment, and the presence of additional factors other than internalizing/externalizing dimensions that can influence PD factor loadings (e.g., Thought Disorder). Although internalizing and externalizing factors are present in each study, these factors are separate for Axis I and II disorders in Kendler et al. (2011) and Roysamb et al. (2011). In each study ASPD loadings for the externalizing factor stand apart from other PDs, with lower but significant loadings for borderline and other Cluster B disorders. Cluster A and C PDs load on the internalizing factor, but schizoid and schizotypal PDs have higher loadings for a Thought Disorder factor (Kotov et al., 2011). In Roysamb et al. (2011) both of the PD factors (Cognitive-relational Disturbance and Anhedonic Introversion) have moderately high correlations with each other and internalizing Axis I disorders.

Finally, a number of study limitations need to be highlighted. Foremost among these relates to the exploratory nature of this study. As such, the findings of this study need to be replicated in other national surveys. Second, diagnoses of disorders were based on structured interviews by lay interviewers and, while informed by DSM-IV criteria, are not clinical assessments and are based on retrospective self-reports. Admittedly, the NESARC has demonstrated fair to good reliability for all 10 DSM-IV PDs in the general population, provided extensive information including their prevalence, correlates, and comorbidity, and their important role in the incidence and persistence of other disorders (Eaton et al., 2012; Hasin et al., 2011; Skodol et al., 2011). Third, the one-time assessment of PD limits this study to cross-sectional analysis and does not allow assessment of directionality between PD and other lifetime Axis I disorders. Fourth, the PDs were assessed at different time periods and may have introduced some bias in the associations with Axis I disorders at Wave 2, although Eaton and colleagues (2011) compared Wave 2 borderline PD with Wave 1 borderline-related constructs found no evidence for bias related to differential follow-up. As a sensitivity analysis, we conducted hierarchical ESEM models separately for Wave 1 and 2 PD assessments and the regression coefficients were similar to those in the full model. Therefore, our findings are robust despite this limitation.

In conclusion, findings from this national study provide strong support for associations between PDs and the externalizing/internalizing latent structure underlying common psychiatric disorders, but a number of issues beyond the scope of this study need to be addressed in subsequent analyses. The presence of a general PD factor, for example, would suggest the use of hierarchical modeling, the absence of which may confound specific PD associations with other Axis I disorders (Jahng et al., 2011). In addition to the need for replication of the present findings in other general population studies, more conceptually focused studies are required for understanding the role of PDs and internalizing factors for fear and distress.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and should not be construed to represent the views of the sponsoring organizations, agencies, or the Federal Government.

Role of Funding Source

This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), National Institutes of Health (NIH), and by the Alcohol Epidemiologic Data System funded by NIAAA Contract No.HHSN267200800023C to CSR, Incorporated.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributors

TCH, CMC, TDS, SMS, WJR, and BFG designed the research; TCH, CMC, and TDS analyzed data; TCH, CMC, and TDS wrote the manuscript; TCH had primary responsibility for the final content of the manuscript, and all authors provided critical input in the writing of the manuscript and read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. American Psychiatric Association; Washington: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Asparouhov T, Muthén B. Exploratory structural equation modeling. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 2009;16:397–438. [Google Scholar]

- Beesdo-Baum K, Hofler M, Gloster AT, Klotsche J, Lieb R, Beauducel A, Bühner M, Kessler RC, Wittchen HU. The structure of common mental disorders: A replication study in a community sample of adolescents and young adults. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2009;18:204–220. doi: 10.1002/mpr.293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;107:238–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn R, Logan C, Renwick SJ, Donnelly JP. Higher-order dimensions of personality disorder: Hierarchical structure and relationships with the five-factor model, the interpersonal circle, and psychopathy. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2005;19:597–623. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2005.19.6.597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coid J, Yang M, Tyrer P, Roberts A, Ullrich S. Prevalence and correlates of personality disorder in Great Britain. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;188:423–431. doi: 10.1192/bjp.188.5.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox BJ, Clara IP, Enns MW. Posttraumatic stress disorder and the structure of common mental disorders. Depression and Anxiety. 2002;15:168–171. doi: 10.1002/da.10052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox BJ, Clara IP, Worobec LM, Grant BF. An empirical evaluation of the structure of DSM-IV personality disorders in a nationally representative sample: Results of confirmatory factor analysis in the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions Waves 1 and 2. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2012 doi: 10.1521/pedi.2012.26.6.890. published online ahead of print August 1, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowson JH, Berrios GE. Factor structure of DSM-III-R personality disorders shown by self-report questionnaire: Implications for classifying and assessing personality disorders. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1991;84:555–560. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1991.tb03194.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton NR, Krueger RF, Keyes KM, Skodol AE, Markon KE, Grant BF, Hasin DS. Borderline personality disorder co-morbidity: Relationship to the internalizing-externalizing structure of common mental disorders. Psychological Medicine. 2011;41:1041–1050. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710001662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton NR, Krueger RF, Markon KE, Keyes KM, Skodol AE, Wall M, Hasin DS, Grant BF. The structure and predictive validity of the internalizing disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2012 doi: 10.1037/a0029598. published online ahead of print August 20, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer RF, Seeley JR, Kosty DB, Lewinsohn PM. Refinements in the hierarchical structure of externalizing psychiatric disorders: Patterns of lifetime liability from mid-adolescence through early adulthood. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2009;118:699–710. doi: 10.1037/a0017205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fossati A, Maffei C, Bagnato M, Battaglia M, Donati D, Donini M, Fiorilli M, Novella L, Prolo F. Patterns of covariation of DSM-IV personality disorders in a mixed psychiatric sample. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2000;41:206–215. doi: 10.1016/S0010-440X(00)90049-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Chou SP, Goldstein RB, Huang B, Stinson FS, Saha TD, Smith SM, Dawson DA, Pulay AJ, Pickering RP, Ruan WJ. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV borderline personality disorder: results from the Wave 2 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2008;69:533–545. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Dawson DA, Hasin DS. The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule—DSM-IV Version. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; Bethesda, MD: 2001a. [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Dawson DA, Stinson FS, Chou PS, Kay W, Pickering R. The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-IV (AUDADIS-IV): Reliability of alcohol consumption, tobacco use, family history of depression and psychiatric diagnostic modules in a general population sample. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2003;71:7–16. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(03)00070-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Chou SP, Huang B, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Saha TD, Smith SM, Pulay AJ, Pickering RP, Ruan WJ, Compton WM. Sociodemographic and psychopathologic predictors of first incidence of DSM-IV substance use, mood and anxiety disorders: Results from the Wave 2 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Molecular Psychiatry. 2009;14:1051–1066. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Harford TC, Dawson DA, Chou PS, Pickering RP. The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview schedule (AUDADIS): Reliability of alcohol and drug modules in a general population sample. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1995;39:37–44. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(95)01134-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Hasin DS, Blanco C, Stinson FS, Chou SP, Goldstein RB, Dawson DA, Smith S, Saha TD, Huang B. The epidemiology of social anxiety disorder in the United States: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2005a;66:1351–1361. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Hasin DS, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Ruan WJ, Pickering RP. Prevalence, correlates, and disability of personality disorders in the United States: Results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2004a;65:948–958. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n0711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Hasin DS, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Ruan WJ, Huang B. Co-occurrence of 12-month mood and anxiety disorders and personality disorders in the US: Results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2005b;39:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2004.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Moore TC, Shepard J, Kaplan K. Source and accuracy statement, Wave 1 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; Bethesda, MD: 2001b. [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Dufour MC, Compton W, Pickering RP, Kaplan K. Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2004b;61:807–816. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.8.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Ruan WJ. Co-occurrence of DSM-IV personality disorders in the United States: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2005c;46:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2004.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harford TC, Chen CM, Saha TD, Smith SM, Hasin DS, Grant BF. An item response theory analysis of DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for personality disorders: Findings from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Personality Disorder: Theory, Research, and Treatment. 2012 doi: 10.1037/a0027416. published online ahead of print March 26, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin D, Carpenter KM, McCloud S, Smith M, Grant BF. The alcohol use disorder and associated disabilities interview schedule (AUDADIS): Reliability of alcohol and drug modules in a clinical sample. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1997;44:133–141. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(97)01332-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin D, Fenton MC, Skodol A, Krueger R, Keyes K, Geier T, Greenstein E, Blanco C, Grant B. Personality disorders and the 3-year course of alcohol, drug, and nicotine use disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2011;68:1158–1167. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Goodwin RD, Stinson FS, Grant BF. Epidemiology of major depressive disorder: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcoholism and Related Conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:1097–1106. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.10.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Huprich SK, Schmitt TA, Richard DC, Chelminski I, Zimmerman MA. Comparing factor analytic models of the DSM-IV personality disorders. Personality Disorder: Theory, Research, and Treatment. 2010;1:22–37. doi: 10.1037/a0018245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahng S, Trull TJ, Wood PK, Tragesser SL, Tomko R, Grant JD, Bucholz KK, Sher KJ. Distinguishing general and specific personality disorder features and implications for substance dependence comorbidity. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2011;120:656–669. doi: 10.1037/a0023539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Aggen SH, Knudsen GP, Roysamb E, Neale MC, Reichborn-Kjnnerudit T. The structure of genetic and environmental risk factors for syndromal andsubsyndromalcommon DSM-IV axis 1 and all axis 11 disorders. American Journal Psychiatry. 2011;168:29–39. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10030340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Prescott CA, Myers J, Neale MC. The structure of genetic and environmental risk factors for common psychiatric and substance use disorders in men and women. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60:929–937. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.9.929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes KM, Eaton NR, Krueger RF, Skodol AE, Wall MM, Grant B, Siever LT, Hasin DS. Thought disorder in the meta-structure of psychopatholgy. Psychological Medicine. 2012;21:1–11. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712002292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotov R, Ruggero CJ, Krueger RF, Watson D, Yuan Q, Zimmerman M. New dimensions in the quantitative classificationof mental illness. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2011;68:1003–1011. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Silva PA. The structure and stability of common mental disorders (DSM-III-R): A longitudinal-epidemiological study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1998;107:216–227. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.2.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF, Eaton NR. Personality traits and the classification of mental disorders: Toward a more complete integration in DSM-5 and an empirical model of psychopathology. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment. 2010;1(2):97–118. doi: 10.1037/a0018990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF, Markon KE, Patrick CJ, Iacono WG. Externalizing psychopathology in adulthood: A dimensional-spectrum conceptualization and its implications for DSM-V. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114:537–550. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.4.537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenzenweger MF, Lane MC, Loranger AW, Kessler RC. DSM-IV personality disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biological Psychiatry. 2007;62:553–564. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markon KE. Modeling psychopathology structure: A symptom level analysis of Axis I and Axis II disorders. Psychological Medicine. 2010;40:273–288. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709990183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markon KE, Krueger RF. Categorical and continuous models of liability to externalizing disorders: a direct comparison in NESARC. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:1352–1359. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.12.1352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh HW, Ludtke O, Muthen B, Asparouhov T, Morin AJ, Trautwein U, Nagengast B. A new look at the big five factor structure through exploratory structural equation modeling. Psychological Assessment. 2010;22:471–491. doi: 10.1037/a0019227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh HW, Muthén B, Asparouhov T, Lüdtke O, Robitzsch A, Morin AJS, Trautwein U. Exploratory structural equation modeling, integrating CFA and EFA: Application to students’ evaluations of university teaching. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 2009;16:439–476. [Google Scholar]

- McGlashan TH, Grilo CM, Skodol AE, Gunderson JG, Shea MT, Morey LC, Zanarini MC, Stout RL. The Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study: Baseline Axis I/II and II/II diagnostic co-occurrence. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2000;102:256–264. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2000.102004256.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide, version 6. Muthén and Muthén; Los Angeles, CA: 1998-2010. [Google Scholar]

- Nestadt G, Hsu FC, Samuels J, Bienvenu OJ, Reti I, Costa PT, Jr., Eaton WW. Latent structure of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition personality disorder criteria. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2006;47:54–62. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2005.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulay AJ, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Goldstein RB, Chou SP, Huang B, Saha TD, Smith SM, Pickering RP, Ruan WJ, Hasin DS, Grant BF. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV schizotypal personality disorder: Results from the Wave 2 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Primary Care Companion to Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2009;11:53–67. doi: 10.4088/pcc.08m00679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roysamb E, Kendler KSm Tambs K, Orstavik RE, Neale MC, Aggen SH, Torgersen S, Reichborn-Kjennerudit T. The joint structure of DSM-IV Axis I and Axis II disorders. Journal Abnormal Psychology. 2011;120:198–209. doi: 10.1037/a0021660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruan WJ, Goldstein RB, Chou SP, Smith SM, Saha TD, Pickering RP, Dawson DA, Huang B, Stinson FS, Grant BF. The alcohol use disorder and associated disabilities interview schedule-IV (AUDADIS-IV): Reliability of new psychiatric diagnostic modules and risk factors in a general population sample. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;92:27–36. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skodol AE, Grilo CM, Keyes KM, Geier T, Grant BF, Hasin DS. Relationship of personality disorders to the course of major depressive disorder in a nationally representative sample. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2011;168:257–264. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10050695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Chou S, Smith S, Goldstein RB, Ruan WJ, Grant BF. The epidemiology of DSM-IV specific phobia in the USA: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychological Medicine. 2007;37:1047–1059. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707000086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Goldstein RB, Chou SP, Huang B, Smith SM, Ruan WJ, Pulay AJ, Saha TD, Pickering RP, Grant BF. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV narcissistic personality disorder: Results from the Wave 2 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2008;69:1033–1045. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart S, Pfohl B, Battaglia M, Bellodi L, Grove W, Cadoret R. The cooccurrence of DSM-III-R personality disorders. Journal of Personality Disorders. 1998;12:302–315. doi: 10.1521/pedi.1998.12.4.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trull TJ, Jahng S, Tomko RL, Wood PK, Sher KJ. Revised NESARC personality disorder diagnoses: gender, prevalence, and comorbidity with substance dependence disorders. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2010;24:412–426. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2010.24.4.412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trull TJ, Verges A, Wood PK, Jahng S, Sher KJ. The structure of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th edition, text revision) personality disorder symptoms in a large national sample. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment. 2012;3:355–369. doi: 10.1037/a0027766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vollebergh WA, Iedema J, Bijl RV, de Graaf R, Smit F, Ormel J. The structure and stability of common mental disorders: the NEMESIS study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2001;58:597–603. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.6.597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman M, Rothschild L, Chelminski I. The prevalence of DSM-IV personality disorders in psychiatric outpatients. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162:1911–1918. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.10.1911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.