Abstract

Purpose

Code status discussions are important in cancer care. The best modality for such discussions has not been established. Our objective was to determine the impact of a physician ending a code status discussion with a question (autonomy approach) versus a recommendation (beneficence approach) on patients' do-not-resuscitate (DNR) preference.

Methods

Patients in a supportive care clinic watched two videos showing a physician-patient discussion regarding code status. Both videos were identical except for the ending: one ended with the physician asking for the patient's code status preference and the other with the physician recommending DNR. Patients were randomly assigned to watch the videos in different sequences. The main outcome was the proportion of patients choosing DNR for the video patient.

Results

78 patients completed the study. 74% chose DNR after the question video, 73% after the recommendation video. Median physician compassion score was very high and not different for both videos. 30/30 patients who had chosen DNR for themselves and 30/48 patients who had not chosen DNR for themselves chose DNR for the video patient (100% v/s 62%). Age (OR=1.1/year) and white ethnicity (OR=9.43) predicted DNR choice for the video patient.

Conclusion

Ending DNR discussions with a question or a recommendation did not impact DNR choice or perception of physician compassion. Therefore, both approaches are clinically appropriate. All patients who chose DNR for themselves and most patients who did not choose DNR for themselves chose DNR for the video patient. Age and race predicted DNR choice.

Keywords: Code status, advanced cancer, communication, patient preferences

Introduction

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) is part of the standard of care for patients that experience cardiac arrest during hospital admissions. The “do not resuscitate” (DNR) order legally documents that patients do not wish to pursue CPR in the event of a cardiopulmonary arrest. CPR has a low success rate in patients with advanced cancer 1. CPR can also have negative consequences in this population, such as physical distress, loss of dignity and family suffering with complicated bereavement 2. Studies have shown that the majority of patients who survive after CPR, die within days to weeks in the intensive care unit (ICU) and few of them regain their previous functional status3-5. Due to these consequences DNR status is generally considered appropriate for patients with advanced cancer6. However, the prevalence of DNR orders for these patients is only around 50%7, 8.

Given that a majority of cancer patients die with mental impairment, conducting code status discussions earlier in the illness is highly important in this population 6, 9, 10. Discussions about code status are generally stressful and difficult for both patients and clinicians involved11. These discussions typically include a description of the interventions, their effectiveness and the patient's preference.

Not all patients feel comfortable expressing a code status preference. Although autonomous decision making is highly valued in the health care environment, studies have shown that the proportion of patients that prefer a shared decision making style is larger than those who prefer an active or passive role12-14. In this context, it is crucial that physicians explore patients' communication preferences in order to guide the conversation accordingly. However, physicians are not always accurate at assessing patient's decision making style14, 15. In fact, agreement between patient decision making preference and physician's perception of this preference occur in only 45% of the cases 14.

Some progress has been made in understanding the factors that influence patient-physician communication in the context of advanced care planning. The content and the manner of the message delivered, environmental factors and both patient and physician characteristics influence end-of-life communication13,16-21. However, the impact of the physician's communication strategy in DNR discussions has not been studied in randomized controlled trials.

The aim of this study was to determine the impact of physician's communication style, promoting patient autonomy versus promoting beneficence, on patient preferences regarding code status by exposing patients to two video scenarios. We hypothesized that patients who received a recommendation regarding code status would more frequently choose not to be resuscitated as compared to patients who did not receive a recommendation.

Methods

Patients

Patients who attended the Supportive Care Clinic at MD Anderson Cancer Center between August and October 2011 were screened and subsequently asked to participate if deemed eligible for this study. Patients were included if they were 18 years or older and had a diagnosis of advanced cancer (defined as locally advanced, recurrent or metastatic disease) and were referred to the Supportive Care Clinic. Non-English patients and those with impaired cognition were excluded. The Institutional Review Board at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center approved this study and all patients gave written informed consent.

Videos

Discussions regarding DNR occur in a large variety of circumstances. The variation in the characteristics of the physician, environment (outpatient clinics, emergency rooms and intensive care units) and clinical situations could make the interpretation of the impact of communication strategies impossible. Therefore we produced a standardized scenario with professional actors, reflecting an encounter in an outpatient setting. This approach has been used by our team before17, 22.

We produced two videos involving a middle age male Caucasian physician discussing code status with a female Caucasian patient who has advanced cancer and a life expectancy of weeks to months. The gender and race of the two actors were chosen to reflect typical consultations at a cancer center. Both videos included 5 minutes of a code status discussion, and were identical in every way except for the last sentence. The first video ended with the physician asking the patient for her code status preference (question scenario – autonomy driven approach) and the second video ended with the physician recommending DNR for the patient (recommendation scenario – beneficence driven approach).

Both videos involved the same professional actors who were blinded to the objective of the study. The script reflected components of ideal physician communication styles identified from research literature, including breaking bad news in an empathic manner, eliciting patient preferences towards decision making 14, and addressing patient concerns and information needs23, 24. The video's design, content and structure was reviewed and edited for appropriateness and accuracy by 2 medical oncologists, 2 palliative care physicians and 1 psychiatrist specializing in patient-physician communication.

Randomization and blinding

Prior to randomization, patients were stratified according to the decision-making preferences questionnaire (DMPQ). DMPQ is a 5-item questionnaire that contains questions regarding decision-making preferences and groups patients into three categories: active, passive, shared. It has been previously used in studies on cancer patients14, 25. The aim of the stratification was to obtain 2 homogeneous groups in terms of decision making preferences (active / passive / shared). According to DMPQ, patients were then randomized between two possible video sequences based on computer-generated random numbers (complete randomization): the first video ending with a question and the second video ending with a recommendation (sequence A), or the first video ending with a recommendation and the second video ending in a question (sequence B).

In previous studies, we observed that the sequence patients watch a video had impact on their perception of physician's compassion. These studies suggest that patients generally prefer the doctor they see in the second video. [23, 24] To control this effect, we used a crossover design to assess the effect of sequence order on ratings of compassion and overall preference.

Both the research assistant in charge of conducting the assessments and the patients were blinded to the allocation sequence throughout the study. Patients were blinded to the hypotheses of the study.

Measures

We collected patient data such as age, sex, ethnicity, religious affiliation, marital status, highest educational level, cancer diagnosis, date of cancer initial diagnosis. Symptom burden was documented using validated Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale (ESAS) 26-29. We also documented strength of religious faith using the Abbreviated Santa Clara Strength of Religious Faith Questionnaire 30, 31 as religious faith have been reported to influence patient preferences regarding end-of-life 32, 33. This tool has been validated for cancer patients 34.

After the first and second video, all patients were asked for code status preference if they were the patient they just watched, their overall preference for communication style of the first physician on a 0 to 10 scale and the physician compassion assessed by a validated 5-item tool consisting of 0–10 numerical rating scales (with 0 for warm and 10 for cold; pleasant-unpleasant; compassionate-distant; sensitive-insensitive; caring-uncaring) 17, 35.

After these assessments, patients were asked if they have had a previous code status discussion with their doctor and if they have made a decision regarding CPR.

Statistical considerations

Patient characteristics and baseline measurements were analyzed with simple parametric or non-parametric statistical methods as appropriate for each variable.

The primary objective of the study was to evaluate the difference in DNR choice of patients exposed to one of the two videos (after the first video). This primary objective was analyzed by contingency table analysis. A two-sided chi-square test of equal proportions was performed. We estimated that with 78 patients (39 patients per arm), the study would have 80% power to detect an odds ratio of 4.0 or larger (50% DNR after watching the first video of the sequence A versus 80% DNR after watching the first video of the sequence B) when alpha=0.05. Total accrual for the study will be 78 patients.

We analyzed the binary DNR preference variable using crossover methodology proposed by Kenward and Jones 36. Briefly, a chi-square test was performed on a two by two contingency table that includes the patients that had a shift response after watching both videos. This chi-square test tested the intervention effect by comparing the response shifts between the two groups.

We analyzed compassion (and other secondary variables) using standard two-stage crossover methodology 37. All tests were two sided, and P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3 (Cary, NC).

Results

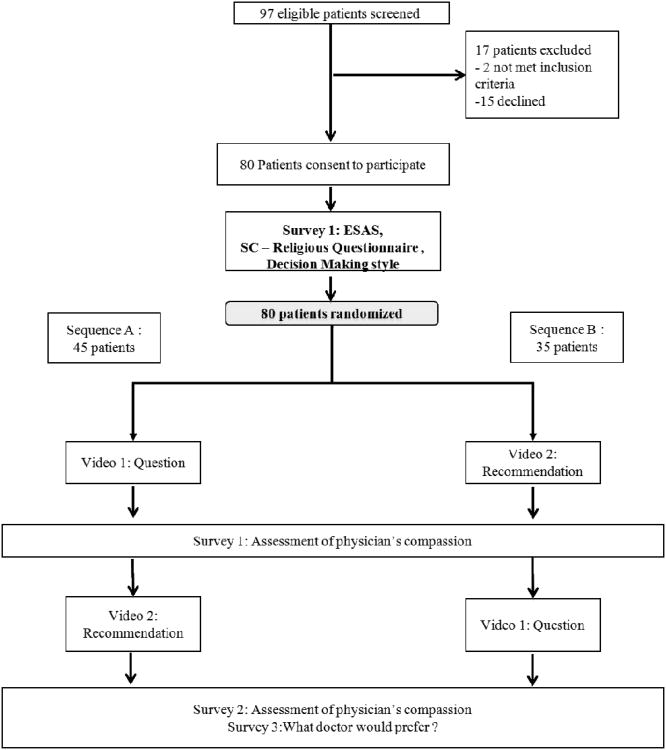

A total of 97 patients were approached for the study, 80 were finally included and 78 patients completed the study (figure 1). Baseline demographics, symptom intensity, anxiety and depression and religiosity were similar in both study arms (Table 1). The study population preferred a shared decision making style over an active or passive decision making style and the distribution was similar in both groups. 30 patients (38%) stated that their code status was DNR and eight patients (10%) said that their code status was CPR. 40 patients (52%) from our study population had not made a decision regarding their own code status at the time of the study. Only 3 (4%) patients in our study had their code status explicitly written in their chart.

Figure 1. Consort diagram of study process and participants' flow.

Table 1. Baseline patient characteristics.

| Patient characteristics | Sequence A: (Q – R) N= 45 | Sequence B: (R – Q) N=35 | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Mean age (SD) | 53 (15) | 52 (13) | 0.81ˆ |

|

| |||

| Female (%) | 25 (56) | 21 (60) | 0.69* |

|

| |||

| Married (%) | 28 (62) | 19 (54) | 0.47* |

|

| |||

| Highest education level (%) | 0.94* | ||

| High school or below | 19 (42) | 16 (46) | |

| Any college education | 21 (47) | 15 (43) | |

| Advanced degree | 5 (11) | 4 (11) | |

|

| |||

| Race (%) | 0.47** | ||

| White | 32 (71) | 27 (77) | |

| Black | 8 (18) | 7 (20) | |

| Other | 5 (11) | 1 (3) | |

|

| |||

| Religion (%) | 0.48* | ||

| Baptist | 6 (13) | 9 (26) | |

| Catholic | 8 (18) | 5 (14) | |

| Christian/Protestant | 9 (20) | 8 (23) | |

| Other | 22 (49) | 13 (37) | |

|

| |||

| Cancer diagnosis (%) | 0.05** | ||

| Lung | 10 (22) | 1 (3) | |

| Gastrointestinal | 9 (20) | 9 (26) | |

| Genitourinary | 8 (18) | 3 (9) | |

| Breast | 3 (7) | 6 (17) | |

| Other | 15 (33) | 16 (45) | |

|

| |||

| Time from cancer diagnosis in months [median (IQR)] | 26 (13, 54) | 22 (10, 63) | 0.83† |

|

| |||

| ESAS [median (IQR) ] | |||

| Pain | 3 (2, 6) | 3 (1, 6) | 0.95† |

| Fatigue | 4 (2, 5) | 5 (3, 7) | 0.10† |

| Nausea | 0 (0, 3) | 1 (0, 3) | 0.36† |

| Depression | 2 (0, 4) | 2 (0, 4) | 0.51† |

| Anxiety | 2 (0, 4) | 2 (0, 4) | 0.88† |

| Drowsiness | 2 (0, 5) | 3 (2, 4) | 0.06† |

| Shortness of breath | 2 (0, 3) | 3 (1, 5) | 0.03† |

| Lack of appetite | 3 (1, 6) | 4 (1, 5) | 0.57† |

| Sleep | 4 (2, 5) | 4 (3, 5) | 0.35† |

| Well being | 4 (3, 5) | 4 (2, 5) | 0.79† |

|

| |||

| SC – Religious Questionnaire [median (IQR)] | 18 (14, 20) | 16 (13, 20) | 0.40† |

|

| |||

| Decision Making style | 0.95* | ||

| Active | 13 (29) | 9 (23) | |

| Shared | 27 (60) | 22 (66) | |

| Passive | 5 (11) | 4 (11) | |

|

| |||

| Do you have a code status? (n=78) | 0.08** | ||

| No | 20 (44) | 20 (61) | |

| Yes, DNR | 22 (49) | 8 (24) | |

| Yes, CPR | 3 (7) | 5 (15) | |

Q= Video ending with a question/R= Video ending with a recommendation. ESAS, Edmonton Symptom Assessment System; SC, Santa Clara Religious Faith Questionnaire; IQR: interquartile range (Q1-Q3);

t-test;

Chi-sq test;

Fischer exact test;

Wilcoxon rank sum test (two-sided)

Fifty-eight patients chose DNR after the first video. There was no difference in the proportion of patients who chose DNR for the patient according to the type of video (Question video v/s Recommendation video) after the first video in both sequence (respectively 34/58 (59%) v/s 24/58 (41%); p=0.49).

We did not found any significant association between DNR choice for the patient in the first video and symptom burden (ESAS; pain, p=0.14; fatigue, p=0.34; nausea, p=0.82; depression, p=0.61; anxiety, p=0.70; drowsiness, p=0.72; shortness of breath, p=0.16; lack of appetite, p=0.83; sleep, p=0.34; well-being, p=0.47) as well as with religious faith (p=0.70) and decisions making preference style (p=0.34).

The proportion of patients that chose DNR for the video patient was not influenced by the period the videos were watched (Period 1 v/s Period 2: 56 (72%) v/s 59 (76%); p=0.58). For the crossover analysis, table 2 describes the combinations of responses each patient had after watching both videos. The two groups were not significantly different in the effect the videos had on patient response shift regarding DNR preference (Table 2).

Table 2.

Number of patients who chose the 4 possible sequences of responses after watching both videos.

| Stable | Shift | Shift | Stable | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | no DNR/no DNR | no DNR/DNR | DNR/no DNR | DNR/DNR | Total |

| 1 (Sequence Q-R) | 10 | 1* | 0* | 34 | 45 |

| 2 (Sequence R-Q) | 8 | 3* | 1* | 21 | 33 |

| Total | 18 | 4* | 1* | 55 | 78 |

Q= Question Video

R= Recommendation Video

Two-tailed Fisher's exact test (p=1)

After watching the first video, the median patients' rating for overall preference for communication (0 - 10) was 9 (IQR: 8, 10) and for compassion score (0 - 50) was 6 (IQR: 0, 13). There were no differences among the two groups (p=0.93 and p=0.53 for overall preference for communication and compassion score respectively). There were no significant differences in the overall physician impression score according to the type of video watched or to the period the videos were watched (p=0.73 and p=0.86, respectively). There was no video or period effect for physicians' compassion score either (p=0.45 and p=0.47, respectively). Compassion score was significantly associated to DNR choice after the first video (p=0.04), with patients that did not chose DNR giving a worst score than patients that chose DNR.

In order to identify predictor variables of choosing DNR for the video patients, we did a subgroup analysis. 60 patients (77%) chose at least for one of the videos a DNR order for the video patient (Table 2). 30 out of 30 patients who chose DNR for themselves chose DNR for the video patient, while 30 out of 48 patients who did not choose DNR for themselves, chose DNR for the video patient (100% v/s 62%, p<0.0001) (Table 3). Patients who chose DNR for the video patient were older, more likely to be married and were predominantly white (Table 4). In multivariate analysis that included age, race, gender, marital status, education and religion, both age (OR=1.016 per year, p =0.01) and race (OR=9.43, p=0.004) were independent predictors.

Table 3.

Comparison of personal code status and code status chosen for the video patient.

| Personal Code Status | Code status chosen for the video patient | Total n (%) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Not DNR n (%) | DNR+ n (%) | |||

|

| ||||

| Not DNR | 18 (37) | 30 (63) | 48 (62) | <0.001* |

| DNR | 0 (0) | 30 (100) | 30 (38) | |

|

| ||||

| Total | 18 (23) | 60 (77) | 78 (100) | |

Patients were defined to have chosen DNR for the video patient if they chose it either for patient in Video 1 or Video 2.

Chi-square.

Table 4. Subgroup Analysis.

| DNR preference for video patient | DNR preference for patients themselves | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNR (N=60) | No DNR (N=18) | p-value | DNR (N=30) | No DNR (N=48) | p-value | ||

| Age, mean (SD) | 55 (14) | 45 (12) | 0.01ˆ | 57 (12) | 50 (15) | 0.04ˆ | |

| Female, n (%) N=45 | 32 (71) | 13 (29) | 0.15* | 12 (27) | 33 (73) | 0.01* | |

| Married, n (%) N=45 | 39 (87) | 6 (13) | 0.02* | 21 (47) | 24 (53) | 0.08* | |

| Race | White n (%) N=57 | 49 (86) | 8 (14) | 0.001** | 26 (46) | 31 (54) | 0.002** |

| Black n (%) N=15 | 6 (40) | 9 (60) | 0 (0) | 15 (100) | |||

| Other n (%) N=6 | 5 (83) | 1 (17) | 4 (67) | 2 (33) | |||

t-test;

Chi-sq test;

Fischer exact test

Discussion

Our study shows that an autonomy driven versus a beneficence driven approach to a code status discussion had no impact on patients' DNR preference or overall physician impression. These findings suggest that ending a DNR discussion with a question or a recommendation are both appropriate in the clinical setting. One possible explanation for this negative finding could be that the information provided by the physician in the video was more important than the way the physician ended the code status discussion. This is supported by the high preference for DNR for the video patient overall even among those patients who did not choose DNR for themselves. Although the described scenario was one in which DNR was considered appropriate almost 25% of the patients did not choose DNR with both modalities of communication. More research is needed to better understand factors that influence DNR choices among palliative care outpatients.

A second hypothesis to explain this negative result could be that the compassion and care that a physician provides could be more important than the way a code status discussion ends. Patients perceived the physician as extremely compassionate after watching both videos, suggesting that both approaches (autonomy versus beneficence driven) seemed to be valued as high quality by patients. It is important to highlight that the physicians' scores were higher in this study than what we have reported in other studies using the same tool (mean score, (SD) 41.6 (8.3) v/s 29.5 (12.7)) as well as what was reported by the original authors that used this scale17, 35.

Last, this negative result could be explained by the fact that the two videos were not different enough to show a difference in patient's perception of the physician communication style and that changing the end of the conversation was not a sufficient way to evaluate these two communication strategies (patient autonomy vs. beneficence). Future research should probably use drastically different videos to be sure that we assess different styles of communication for code status discussion.

A very interesting finding in our study is that all patients who had a DNR order for themselves decided they would choose DNR for the video patient. On the other hand, 62% of the patients who did not have a DNR order, said that they would choose a DNR order for the video patient. We hypothesize that the group of patients with advanced cancer who have not chosen a DNR order may have not discussed this issue with their primary doctor, but they are at a stage where they foresee that this alternative is a real and valid option in certain cases. Health care providers who take care of these patients may be missing invaluable opportunities to address this important issue.

In previous studies we found that patients scored physician's compassion significantly higher for the physician observed in the second video17, 22. In the current study the order in which the videos were shown did not modify patient's preference. This finding could also be explained by the masking effect of a highly compassionate physician in the video.

When comparing the patients according to whether they chose DNR for the video patient or not, being older, being married and having a white ethnicity were predictors of choosing DNR. In the multivariate analysis, both age and race were independent predictors of choosing DNR for the video patient. These results are consistent with previous literature by our group and others 6, 38, 39. Several studies have reported increased rate of DNR documentation with age 40-43. Other reports have consistently shown racial difference in DNR preferences. For example, a recent review described that white race is a predictor of having a DNR order 40. Likewise, a recent study showed that black patients are less likely to have a code status documented in their medical record 41.

We also found that most patients (51%) had not made a decision regarding their own code status and that only 4% of the patients had a code status noted in the chart. Our results are consistent with other publications that report that only a small proportion of advanced cancer patients have a DNR order in their medical record despite evidence that shows that advanced care planning and code status discussions is an important part of comprehensive care 41, 44, 45. These results suggest that the remaining 96% with no documentation regarding their code status were exposed to full resuscitative measures, regardless of their preference.

Prior conversation with the oncologist regarding code status is a potential important covariate for this study. We documented patient prior conversation with their oncologist regarding code status; however, only three patients reported a prior discussion and this low frequency did not allow us to use this variable in our multivariate analysis.

Regarding code status discussions, our results suggest that bringing this topic by a question or recommendation will not play an important role on patient final choice but discussions should take place more frequently and they should be systematically documented. In our results, a large proportion of patients (51%) did not make any choice regarding their own code status, suggesting that it might require multiple conversations to allow patients to understand the goals and risks regarding resuscitation in the context of advanced cancer and to make their own choice.

Code status discussions should happen early during the course of illness for every patients and one of the ways to improve the rate of patient documented preferences for code status will be to refer the patient to supportive care teams and to increase educational procedures for both the public and physicians.

Future research should study the impact of repeated conversations to see if patient DNR preferences changes over the times, particularly among outpatients who did not know or who refuse DNR.

The main limitation of this study was that we tested the impact of a standardized video on patient preferences for code status. In clinical practice, physicians are likely to vary in terms of the clarity of the provided information as well as for the empathy of their communication style resulting in differences for patients' preferences. This might limit generalizability of our results to usual code status discussion.

Conclusion

Exposing outpatient cancer patients to two different videotaped patient-physician discussions regarding code status, one ending a DNR discussion with a question and the other one with a recommendation did not significantly impact patients' DNR decisions or perception of physician compassion and therefore both approaches are clinically appropriate. 77% of all the patients chose DNR for the video patient, even though most of them had not chosen DNR for themselves. A DNR order for the video patient was predicted by DNR decision for the patient themselves, older age and being of white ethnicity. More research is needed to develop evidence based communication strategies.

Acknowledgments

Funding sources: The study had no specific funding. Eduardo Bruera is supported in part by National Institutes of Health grants R01NR010162-01A1, R01CA1222292.01, and R01CA124481-01 and in part by the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center support grant CA 016672.

Footnotes

This paper was partially reported at the Annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, Chicago, June 03th 2012

Financial disclosures: The authors made no disclosures.

References

- 1.Reisfield GM, Wallace SK, Munsell MF, Webb FJ, Alvarez ER, Wilson GR. Survival in cancer patients undergoing in-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation: a meta-analysis. Resuscitation. 2006;71:152–160. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2006.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ardagh M. Futility has no utility in resuscitation medicine. J Med Ethics. 2000;26:396–399. doi: 10.1136/jme.26.5.396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Azoulay E, Pochard F, Kentish-Barnes N, et al. Risk of post-traumatic stress symptoms in family members of intensive care unit patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:987–994. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200409-1295OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Embriaco N, Papazian L, Kentish-Barnes N, Pochard F, Azoulay E. Burnout syndrome among critical care healthcare workers. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2007;13:482–488. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e3282efd28a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fu S, Hong DS, Naing A, et al. Outcome analyses after the first admission to an intensive care unit in patients with advanced cancer referred to a phase I clinical trials program. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3547–3552. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.3823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parsons HA, de la Cruz MJ, Zhukovsky DS, et al. Characteristics of patients who refuse do-not-resuscitate orders upon admission to an acute palliative care unit in a comprehensive cancer center. Cancer. 2010;116:3061–3070. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.El-Jawahri A, Podgurski LM, Eichler AF, et al. Use of video to facilitate end-of-life discussions with patients with cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:305–310. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.7502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dow LA, Matsuyama RK, Ramakrishnan V, et al. Paradoxes in advance care planning: the complex relationship of oncology patients, their physicians, and advance medical directives. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:299–304. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.6397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lawlor PG, Gagnon B, Mancini IL, et al. Occurrence, causes, and outcome of delirium in patients with advanced cancer: a prospective study. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:786–794. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.6.786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bush SH, Bruera E. The assessment and management of delirium in cancer patients. Oncologist. 2009;14:1039–1049. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2009-0122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holley A, Kravet SJ, Cordts G. Documentation of code status and discussion of goals of care in gravely ill hospitalized patients. J Crit Care. 2009;24:288–292. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2008.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arora NK, McHorney CA. Patient preferences for medical decision making: who really wants to participate? Med Care. 2000;38:335–341. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200003000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elkin EB, Kim SH, Casper ES, Kissane DW, Schrag D. Desire for information and involvement in treatment decisions: elderly cancer patients' preferences and their physicians' perceptions. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5275–5280. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.1922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bruera E, Sweeney C, Calder K, Palmer L, Benisch-Tolley S. Patient preferences versus physician perceptions of treatment decisions in cancer care. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:2883–2885. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.11.2883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frojd C, Von Essen L. Is doctors' ability to identify cancer patients' worry and wish for information related to doctors' self-efficacy with regard to communicating about difficult matters? Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2006;15:371–378. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2006.00670.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brown VA, Parker PA, Furber L, Thomas AL. Patient preferences for the delivery of bad news - the experience of a UK Cancer Centre. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2011;20:56–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2009.01156.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bruera E, Palmer JL, Pace E, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of physician postures when breaking bad news to cancer patients. Palliat Med. 2007;21:501–505. doi: 10.1177/0269216307081184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baile WF, Glober GA, Lenzi R, Beale EA, Kudelka AP. Discussing disease progression and end-of-life decisions. Oncology (Williston Park) 1999;13:1021–1031. discussion 1031-1026, 1038. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gattellari M, Butow PN, Tattersall MH, Dunn SM, MacLeod CA. Misunderstanding in cancer patients: why shoot the messenger? Ann Oncol. 1999;10:39–46. doi: 10.1023/a:1008336415362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ptacek JT, Eberhardt TL. Breaking bad news. A review of the literature. JAMA. 1996;276:496–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schofield P, Carey M, Love A, Nehill C, Wein S. ‘Would you like to talk about your future treatment options’? Discussing the transition from curative cancer treatment to palliative care. Palliat Med. 2006;20:397–406. doi: 10.1191/0269216306pm1156oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Strasser F, Palmer JL, Willey J, et al. Impact of physician sitting versus standing during inpatient oncology consultations: patients' preference and perception of compassion and duration. A randomized controlled trial. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2005;29:489–497. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2004.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heaven CM, Maguire P. The relationship between patients' concerns and psychological distress in a hospice setting. Psychooncology. 1998;7:502–507. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1611(199811/12)7:6<502::AID-PON336>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McPherson CJ, Higginson IJ, Hearn J. Effective methods of giving information in cancer: a systematic literature review of randomized controlled trials. J Public Health Med. 2001;23:227–234. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/23.3.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Degner LF, Sloan JA. Decision making during serious illness: what role do patients really want to play? J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:941–950. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90110-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carvajal A, Centeno C, Watson R, Bruera E. A comprehensive study of psychometric properties of the Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS) in Spanish advanced cancer patients. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47:1863–1872. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chang VT, Hwang SS, Feuerman M. Validation of the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale. Cancer. 2000;88:2164–2171. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(20000501)88:9<2164::aid-cncr24>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bruera E, MacMillan K, Hanson J, MacDonald RN. The Edmonton staging system for cancer pain: preliminary report. Pain. 1989;37:203–209. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(89)90131-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moro C, Brunelli C, Miccinesi G, et al. Edmonton symptom assessment scale: Italian validation in two palliative care settings. Support Care Cancer. 2006;14:30–37. doi: 10.1007/s00520-005-0834-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Plante T, Vallaeys C, Sherman A, Wallston K. The development of a brief version of the Santa Clara Strength of Religious Faith Questionnaire. Pastoral Psychology. 2002;50:359–368. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Plante T. The Santa Clara Strength of Religious Faith Questionnaire: Assessing Faith Engagement in a Brief and Nondenominational Manner. Religions. 2010;1:3–8. [Google Scholar]

- 32.McKinley ED, Garrett JM, Evans AT, Danis M. Differences in end-of-life decision making among black and white ambulatory cancer patients. J Gen Intern Med. 1996;11:651–656. doi: 10.1007/BF02600155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sullivan MA, Muskin PR, Feldman SJ, Haase E. Effects of religiosity on patients' perceptions of do-not-resuscitate status. Psychosomatics. 2004;45:119–128. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.45.2.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sherman AC, Simonton S, Adams DC, et al. Measuring religious faith in cancer patients: reliability and construct validity of the Santa Clara Strength of Religious Faith questionnaire. Psychooncology. 2001;10:436–443. doi: 10.1002/pon.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fogarty LA, Curbow BA, Wingard JR, McDonnell K, Somerfield MR. Can 40 seconds of compassion reduce patient anxiety? J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:371–379. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.1.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kenward MG, Jones B. Design and Analysis of Cross-Over Trials. In: Rao CR, Miller JP, Rao DC, editors. Handbook of statistics: Epidemiology and medical statistics. 1st. xviii. Amsterdam; Boston: Elsevier; 2008. p. 852. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grizzle JE. The Two-Period Change-over Design an Its Use in Clinical Trials. Biometrics. 1965;21:467–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Messinger-Rapport BJ, Kamel HK. Predictors of do not resuscitate orders in the nursing home. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2005;6:18–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2004.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kwak J, Haley WE. Current research findings on end-of-life decision making among racially or ethnically diverse groups. Gerontologist. 2005;45:634–641. doi: 10.1093/geront/45.5.634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Loertscher L, Reed DA, Bannon MP, Mueller PS. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation and do-not-resuscitate orders: a guide for clinicians. Am J Med. 2010;123:4–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Temel JS, Greer JA, Admane S, et al. Code status documentation in the outpatient electronic medical records of patients with metastatic cancer. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:150–153. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1161-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zweig SC, Kruse RL, Binder EF, Szafara KL, Mehr DR. Effect of do-not-resuscitate orders on hospitalization of nursing home residents evaluated for lower respiratory infections. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:51–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zingmond DS, Wenger NS. Regional and institutional variation in the initiation of early do-not-resuscitate orders. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1705–1712. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.15.1705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fairchild A, Kelly KL, Balogh A. In pursuit of an artful death: discussion of resuscitation status on an inpatient radiation oncology service. Support Care Cancer. 2005;13:842–849. doi: 10.1007/s00520-005-0799-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Curtis JR. Communicating with patients and their families about advance care planning and end-of-life care. Respir Care. 2000;45:1385–1394. discussion 1394-1388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Friedrichsen MJ, Strang PM, Carlsson ME. Breaking bad news in the transition from curative to palliative cancer care--patient's view of the doctor giving the information. Support Care Cancer. 2000;8:472–478. doi: 10.1007/s005200000147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]