Abstract

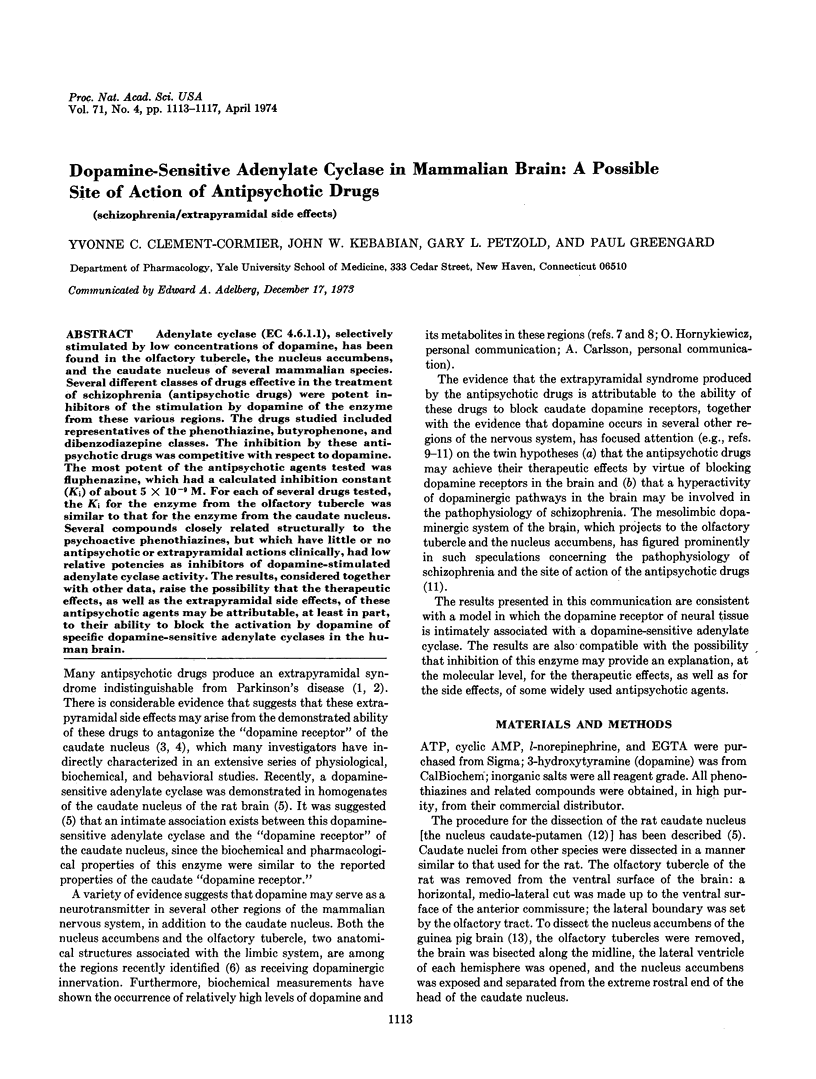

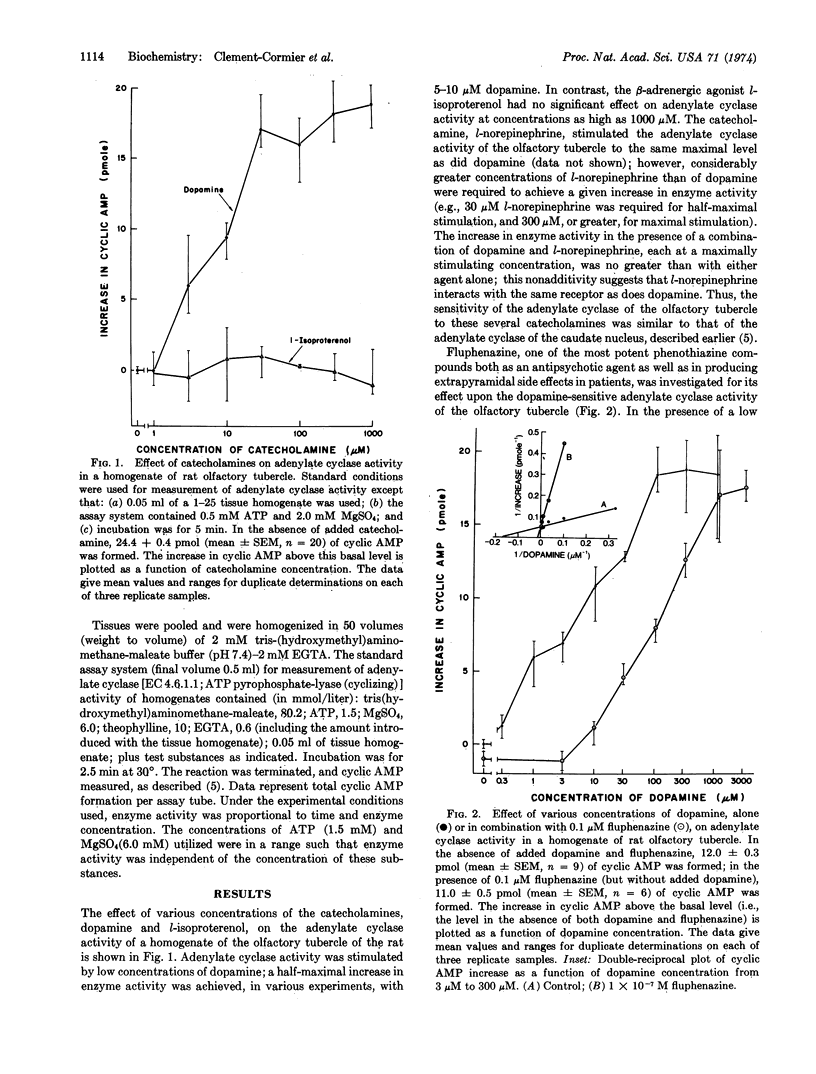

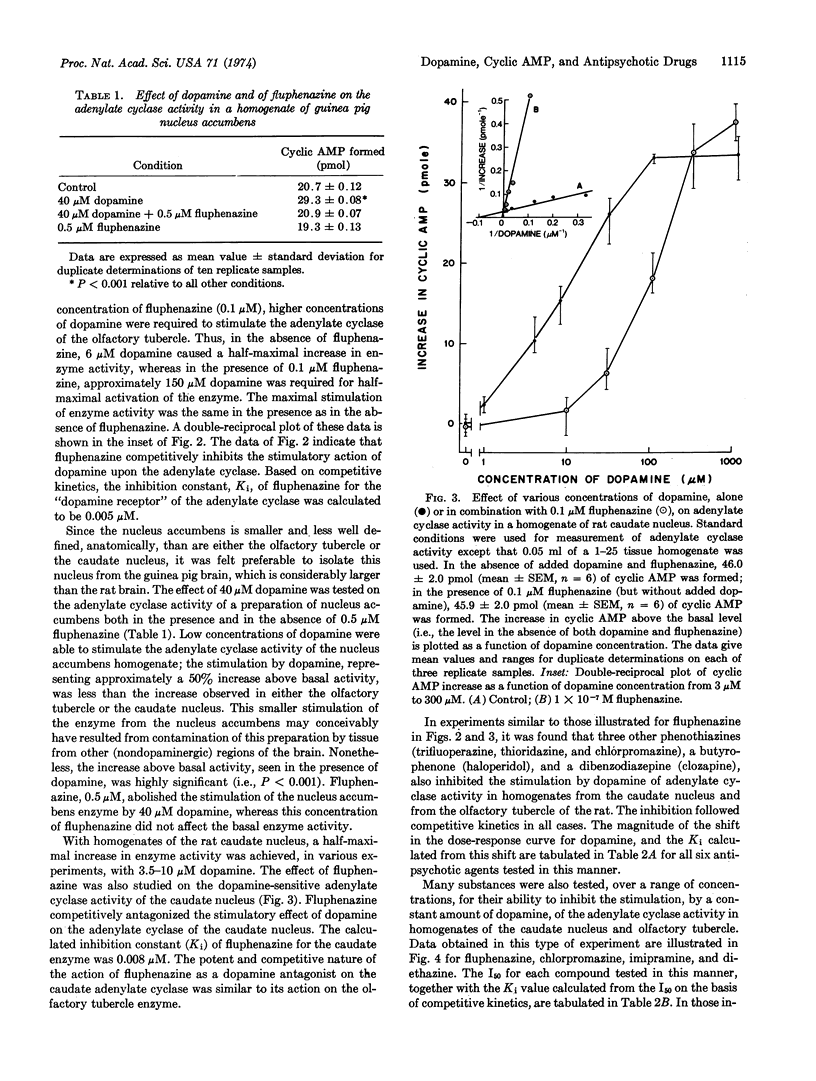

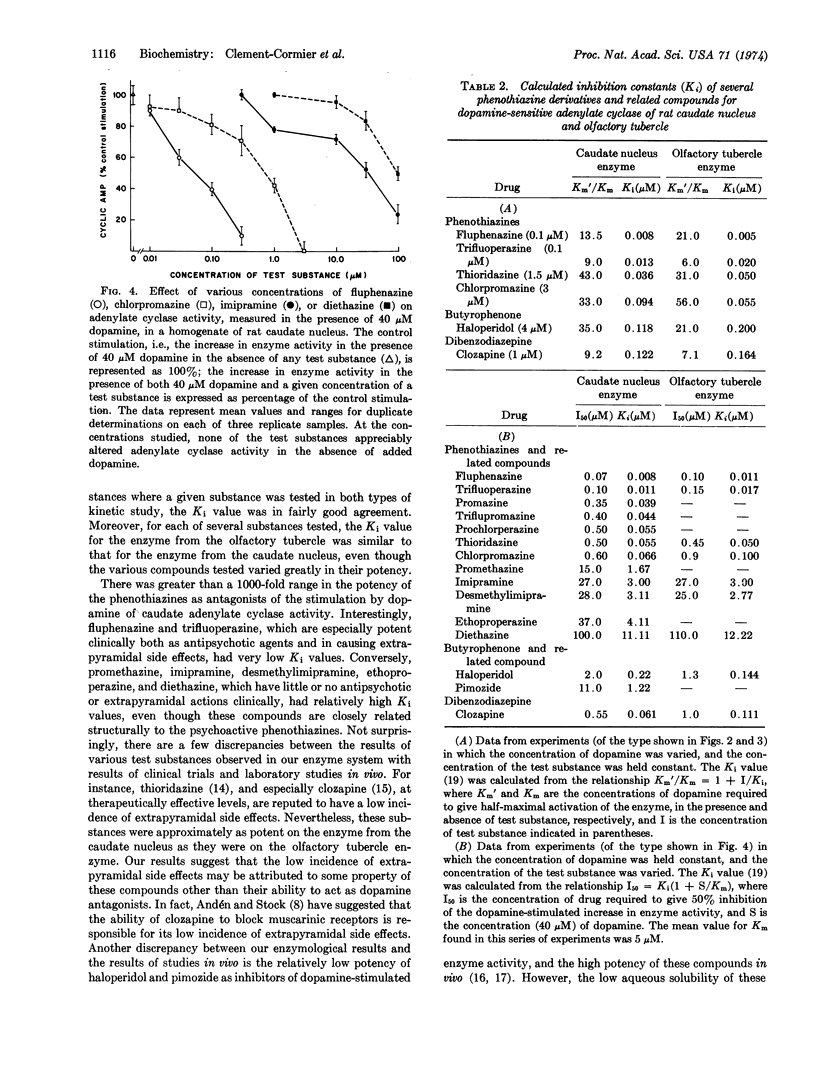

Adenylate cyclase (EC 4.6.1.1), selectively stimulated by low concentrations of dopamine, has been found in the olfactory tubercle, the nucleus accumbens, and the caudate nucleus of several mammalian species. Several different classes of drugs effective in the treatment of schizophrenia (antipsychotic drugs) were potent inhibitors of the stimulation by dopamine of the enzyme from these various regions. The drugs studied included representatives of the phenothiazine, butyrophenone, and dibenzodiazepine classes. The inhibition by these antipsychotic drugs was competitive with respect to dopamine. The most potent of the antipsychotic agents tested was fluphenazine, which had a calculated inhibition constant (Ki) of about 5 × 10-9 M. For each of several drugs tested, the Ki for the enzyme from the olfactory tubercle was similar to that for the enzyme from the caudate nucleus. Several compounds closely related structurally to the psychoactive phenothiazines, but which have little or no antipsychotic or extrapyramidal actions clinically, had low relative potencies as inhibitors of dopamine-stimulated adenylate cyclase activity. The results, considered together with other data, raise the possibility that the therapeutic effects, as well as the extrapyramidal side effects, of these antipsychotic agents may be attributable, at least in part, to their ability to block the activation by dopamine of specific dopamine-sensitive adenylate cyclases in the human brain.

Keywords: schizophrenia, extrapyramidal side effects

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Andén N. E. Dopamine turnover in the corpus striatum and the lumbic system after treatment with neuroleptic and anti-acetylcholine drugs. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1972 Nov;24(11):905–906. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1972.tb08912.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andén N. E., Stock G. Effect of clozapine on the turnover of dopamine in the corpus striatum and in the limbic system. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1973 Apr;25(4):346–348. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1973.tb10025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunney B. S., Walters J. R., Roth R. H., Aghajanian G. K. Dopaminergic neurons: effect of antipsychotic drugs and amphetamine on single cell activity. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1973 Jun;185(3):560–571. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COLE J. O., CLYDE D. J. Extrapyramidal side effects and clinical response to the phenothiazines. Rev Can Biol. 1961 Jun;20:565–574. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y., Prusoff W. H. Relationship between the inhibition constant (K1) and the concentration of inhibitor which causes 50 per cent inhibition (I50) of an enzymatic reaction. Biochem Pharmacol. 1973 Dec 1;22(23):3099–3108. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(73)90196-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornykiewicz O. Neurochemical pathology and pharmacology of brain dopamine and acetylcholine: rational basis for the current drug treatment of Parkinsonism. Contemp Neurol Ser. 1971;8:33–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kebabian J. W., Petzold G. L., Greengard P. Dopamine-sensitive adenylate cyclase in caudate nucleus of rat brain, and its similarity to the "dopamine receptor". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1972 Aug;69(8):2145–2149. doi: 10.1073/pnas.69.8.2145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin J. B. Neural regulation of growth hormone secretion. N Engl J Med. 1973 Jun 28;288(26):1384–1393. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197306282882606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nybäck H., Schubert J., Sedvall G. Effect of apomorphine and pimozide on synthesis and turnover of labelled catecholamines in mouse brain. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1970 Aug;22(8):622–624. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1970.tb10583.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nybäck H., Sedvall G. Effect of chlorpromazine on accumulation and disappearance of catecholamines formed from tyrosine-C14 in brain. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1968 Aug;162(2):294–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder S. H. Catecholamines in the brain as mediators of amphetamine psychosis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1972 Aug;27(2):169–179. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1972.01750260021004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens J. R. An anatomy of schizophrenia? Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1973 Aug;29(2):177–189. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1973.04200020023003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungerstedt U. Stereotaxic mapping of the monoamine pathways in the rat brain. Acta Physiol Scand Suppl. 1971;367:1–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-201x.1971.tb10998.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Maio D. Clozapine, a novel major tranquilizer. Clinical experiences and pharmacotherapeutic hypotheses. Arzneimittelforschung. 1972 May;22(5):919–923. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]