Abstract

Objective

The primary goal was to test the hypothesis that limited social support (SS) is related to shorter leukocyte telomere length (LTL), particularly in an older adult population.

Methods

Cross-sectional analyses were performed on 948 participants at Exam 1 of the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA), ages 45–84 years (18.4% White, 53.1% Hispanics, and 28.5% African-American). LTL was determined using qPCR and social support was measured with the ENRICHD social support inventory.

Results

Across the entire sample, SS was not associated with LTL (p = .87) after adjusting for demographic (age, gender, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status), age X gender, age X race, health (body mass index, diabetes, pulse pressure), and lifestyle factors (smoking, physical activity, diet), however the interaction term Age (dichotomized) X SS was significant, p = .001. Stratification by age group revealed a positive association between SS (score range: 5–25) and LTL in the older (65–84 years) B(SE) = .005(.002), p = .007, but not younger participants (45–64 years), p = .12, after adjusting for covariates.

Conclusions

These results from a racially/ethnically diverse community sample of men and women provide initial evidence that low SS is associated with shorter LTL in adults aged 65 and older and is consistent with the hypothesis that social environment may contribute to rates of cellular aging, particularly in late life.

Keywords: telomere length, social support, cellular aging, loneliness, isolation, older adults

Background

Having limited social resources, few social ties and/or feeling socially isolated, increases risk for age related disease morbidity and mortality, independent of traditional risk factors (1–3). In a recent meta-analysis of 148 studies examining associations between social relationships and mortality risk, relative risk for mortality associated with a lack of social integration was equal to or greater than the increased risk conferred by a number of other established risk factors (i.e. physical activity, obesity, smoking)(3). The socioemotional selectivity theory (4) proposes that there is a shift in motivations to socially engage in late life as a consequence of changes in perceptions of how much time is left in the lifespan. This drives a redirection of attention to emotionally meaningful goals and relationships. However, accompanying this is often a reduction in social network size, which in some instances can increase feelings of isolation when there is a loss or lack of available meaningful relationships. These processes may cause older adults who are limited in social connections to experience feelings of social isolation, which may contribute to greater disease burden and premature death. The mechanisms through which social isolation affects disease vulnerability and death are likely multifaceted. Loneliness and low social support may influence health by altering cognitive appraisals of stress, enhancing the magnitude of autonomic and hypothalamic arousal to daily stress, interfering with restorative processes such as sleep, reducing humoral and viral immune defenses, and enhancing pro-inflammatory activity (5–9). Many of these factors may increase disease risk and premature death by accelerating cellular aging (10–13), which has been implicated in the pathophysiology of physical aging (14–18).

One indicator of cellular aging is telomere length, which acts as a mitotic clock by limiting cellular lifespan. Telomeres are protective protein-DNA complexes that cap the end of chromosomes and shorten with cell division and oxidative damage, thereby reflecting both cell replication history and oxidative stress burden (13; 15; 19; 20). As telomeres progressively shorten over the lifespan, they can reach a critically short length and the cell is forced into a senescent state. This senescent state is characterized by an inability to divide and an altered behavior, including increased secretion of proinflammatory cytokines and extracellular-matrix-degrading enzymes (21; 22). In late life there is increasing proportion of late differentiated cells with short telomeres, putting older adults with shorter telomeres at greater risk for cellular senescence (23; 24). Aging is also accompanied by a rise in inflammation, sometimes referred to as inflammaging (25–27), which is thought to arise from several sources, including senescent cells. Inflammation may contribute to further shortening of telomeres with pathophysiological implications for age-related disease and system aging (14; 28; 29). Initial epidemiological evidence supports the links between aging and leukocyte telomere length (LTL) shortening (24; 30; 34). Old age has been linked to accelerations in LTL shortening compared to earlier adulthood (34). Importantly, this accelerated LTL shortening has been associated with elevated risk for mortality (31; 32).

Later life (especially ages above 65 years) is also a time of increased risk for chronic disease and death. Increasing age is accompanied by more rapid declines in physical functioning and increased frailty (35). This aging phenotype suggests that late life may be a time of particular vulnerability to factors that may affect the aging process.

Given that greater chronic psychological burdens in later life has been associated with shorter LTL (34) and greater inflammation (36), we hypothesized that biological aging, as indexed by leukocyte telomere length, in the later years of life would be magnified in the presence of social disconnection and limited social support. On the other hand, substantial social support may protect adults in late life from accelerations in biological aging.

Although several studies have linked socio-emotional adversities, such as pessimism, psychological stress, and depression, with shorter LTL (11; 12; 33; 37–39), no study to date has examined whether low social support, a particularly important psychosocial factor in older adults, is associated with an older biological age as evidenced by LTL shortening. Consistent with evidence that lack of social support increases risk for age-related disease morbidity and mortality in later years, and declines in physical and biological aging are accelerated in old age, we predicted that observed differences in LTL by social support would be more pronounce in those aged 65 and older.

The primary hypotheses are as follows: 1) Individuals who report high levels of social support will have longer LTL than those who do not. 2) Associations of LTL with social support will be greater in those who are in late life (65 and older).

Methods

2.1 Participants

Data were derived from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA), a longitudinal study of subclinical and clinical cardiovascular disease risk in the United States of America (41), which recruited 6,814 men and women free of clinical cardiovascular disease (ages 45–84 years old) at baseline. Participants were recruited from six US communities (New York City, NY, Los Angeles County, CA, Baltimore, MD, Chicago, IL, Forsyth County, NC, St. Paul, MN) between July 2000 and August 2002 through publicizing the study in local media, targeted recruitment through mailings of letters and brochures, and telephone calls (See (41) for additional details on study objectives and design). The MESA Stress Study, an ancillary study designed to analyze the impact of stress on cardiovascular disease, added a measure of LTL on DNA (preserved from Exam 1) stored from 978 participants recruited from New York and Los Angeles sites (40). From this sample, 1 participant had no physical activity data, 11 participants were missing smoking history data, 15 participants were missing income data, and 3 participants had telomere values that were outliers (> 3 SD from the mean). Thus analyses were performed on 948 participants, 176 (18.6%) White, 502 (53%) Hispanics, and 270 (28.5%) African American (the ancillary study did not enroll any Asian Americans). The demographics, health and lifestyle factors, the Enhancing Recovery in Coronary Heart Disease Patients (ENRICHD) social support inventory (ESSI) and blood samples were obtained from the initial MESA visit (Exam 1). Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the present analyses and the study was approved by Institutional Review Boards of each participating institution (University of California Los Angeles, Columbia University, and the University of Michigan).

2.2 Demographics, health and lifestyle risk factors

Age, gender, racial/ethnic identity, education, and income were recorded from exam 1 interview. Race/ethnicity was classified into four categories, and included white non-Hispanic, Hispanic, and African American. As previous findings have reported associations of LTL with body mass index (BMI) (defined as kg divided by height in meters squared), (42; 43) diabetic status (defined as > or equal to 126 ng/dL fasting glucose or use of diabetic medications) (44), and pulse pressure (defined as Systolic Blood Pressure minus Diastolic Blood Pressure, expressed in mmHg) (45), we selected these as covariates. Likewise, lifestyle risk factors associated with telomere length included in our model are physical activity (Metabolic Equivalent (MET)-min/wk of moderate and vigorous physical activity) (46), smoking history (pack-years cigarette smoked), and consumption of processed meats (previously reported by Nettleton et al. to be associated with LTL in this MESA sample) (46). A full description of these measures has been reported in previous papers (41; 47; 48). Based on prior analyses from MESA(47; 49), educational level was estimated by categorizing into less than high school (HS), high school completion/some college, or bachelor degree (BA) or higher and creating two dummy variables (less than HS = 1, all other = 0; BA or more = 1, all others = 0). Current family income was estimated with the following four categories: less than $20,000, $20–39,999, $40–74,999, or $75,000 or more.

2.3 Social Support

The ENRICHD social support inventory (ESSI) was designed to capture the extent of available social support with fewer items than other common scales to improve compliance and reduce participant burden in large epidemiological samples that typically have multiple questionnaires and physical exams to complete at a visit (50). Responses to the 5 items are on a 5-point likert scale and assess whether there is someone available to the participant who will listen, give advice, show affection/love, provide emotional support, and can be confided in. Scores can range from 5–25. Higher values on this inventory are indicative of greater availability of social support. As reported previously (50; 51), this scale has good reliability, with the 5-item in the present analyses Cronbach’s alpha = .90 (Mitchell et al., 2003 reporting .87 for 5-item), and has been cross validated with longer social support indexes (i.e. Perceived social support scale, r = .63) (50).

2.4 Leukocyte telomere length

The telomere length measurement procedures have been reported previously (40). Briefly, real time quantitative PCR methods were used for the determination of blood leukocyte telomere length (52). This method amplifies, through polymerase chain reaction, the DNA sequence of the telomere (T) and a single copy (S) control gene (36B4) used to normalize values. Cycle threshold (CT) is converted to nanograms of DNA using a standard curve of serial dilutions. Using these values a relative measure of LTL is computed (T/S ratio). Intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation for this assay were 6 and 7%, respectively.

2.5 Analytic Strategy

Descriptive statistics for each predictor are reported by racial/ethnic category. Using chi squared, ANOVA, linear regression, or independent samples t-test, we tested for differences in social support and LTL by levels of covariates.

Linear regression analyses were employed to estimate associations of the continuous variable social support with LTL, with Model1, and all subsequent models, adjusting for age, gender, race/ethnicity, education, and income. Based on prior work in this sample (53), additive interactions between age and race/ethnicity and age and gender were also included in all models. Model 2 includes covariates in Model 1 and makes further adjustments by health factors that have previously been association with LTL including BMI (42), pulse pressure (45), and diabetes status (44). Model 3 includes Model 1 and Model 2 covariates and further adjusts for specific lifestyle factors previously reported to be associated with LTL, including physical activity (46), cigarette smoking, and consumption of processed meats (47). For one covariate, dietary data, there was substantial number of missing values (number missing = 99). To prevent sample size changes in model 3, we replaced missing dietary values with the sample mean. No other missing data was imputed.

Moderation of the association of social support with LTL by age was tested using an age X social support interaction term. For these analyses, age was dichotomized into those under 65 years old (n = 547) and those over 65 years old (n = 401; defined as “elderly” by the US Census). This “older” adults age group includes young-old and middle-old individuals with ages ranging from 65 to 84. Secondary analyses also tested for an interaction of age by social support with age as a continuous variable. All analyses were performed using the full dataset, except for analyses stratified by age.

Results

Descriptive statistics for age, gender, education, income, BMI, smoking, pulse pressure, physical fitness, and percent diabetic by tertile of social support are displayed in Table 1. We found a significant positive association between social support and income (F(3,944) = 6.34, p < .001). Lower social support tended to be associated with more pack-years of smoking (B(SE) = −.02(.01), p = .05). No other demographic or health/lifestyle variables were associated with the ESSI.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for demographic, health, lifestyle, and social support variables in the full sample and by tertile of social support.

| Full sample n = 948 Mean (SD) or % |

Social Support 1st Tertile n = 266 Mean (SD) or % |

Social Support 2nd Tertile n = 347 Mean (SD) or % |

Social Support 3rd Tertile n = 335 Mean (SD) or % |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 61.4(10) | 60.5(9.5) | 62.5(10.1) | 61(10) | .03 |

| Gender (% Male) | 47.5% | 44.7% | 47.3% | 49.9% | .46 |

| Race | .14 | ||||

| White | 18.6% | 19.2% | 21.3% | 15.2% | |

| African-American | 28.5% | 26.3% | 30.5% | 28.1% | |

| Hispanic | 53% | 54.5% | 48.1% | 56.7% | |

| Adult Education | .32 | ||||

| Less than HS Diploma | 26.3% | 26.2% | 24.3% | 28.3% | |

| HS Diploma, Some college | 50.5% | 50% | 49.3% | 52.1% | |

| Completed Bachelor’s Degree | 23.2% | 23.8% | 26.4% | 19.6% | |

| Current Family Income/Year | .002 | ||||

| $0–19,000 | 38.8% | 47.4% | 34% | 37% | |

| $20–39,999 | 25.9% | 26.7% | 27.4% | 23.9% | |

| $40–74,999 | 21.9% | 18.4% | 22.2% | 24.5% | |

| $75,000 and greater | 13.3% | 7.5% | 16.4% | 14.6% | |

| Body Mass Index | 29(5.6) | 29(5.4) | 29(5.7) | 29(5.6) | .99 |

| Pack-Years of Smoking | 8.2(15.7) | 9.4(16.5) | 8.7(16.3) | 6.6(14.2) | .07 |

| Pulse Pressure (mmHg) | 53.3(16.6) | 52.1(15.6) | 53.3(16.9) | 54.3(17) | .27 |

| Physical Activity (MET) | 5691.8(5525) | 5588.7(5397) | 5588.2(5590) | 5881(5570) | .74 |

| % Diabetic | 27.1% | 27.8% | 25.6% | 28.1% | .73 |

| Social Support | 21.1(4.7) | 14.7(3.7) | 22.1(1.5) | 25(0) | NA |

| Leukocyte Telomere Length (T/S) | .84(.17) | .85(.18) | .83(.16) | .84(.17) | .10 |

Note: For descriptive purposes, Table 1 reports p value for ANOVA and Pearson Chi-square analyses using tertile of Emotional Social Support. All regression models in Table 2 and reported in the text test associations with social support as a continuous variable.

Across the entire sample, chronological age was significantly inversely associated with LTL in an unadjusted model, with roughly a .005 shortening of LTL (T/S ratio) with each year increase in age, F(1,947) = 96.74, R2 = .09, p < .001. Moreover, being male (F(1,945) = 21.21, R2 = .02, B(SE) = −.05(.001), p < .001), smoking (F(1,945) = 11.24, R2 = .011, B(SE) = −.001(.00), p < .001), consuming processed meats (F(1,945) = 11.47, R2 = .011, B(SE) = −.075(.02), p < .001), and having lower pulse pressure (F(1,945) = 13.42, R2 = .013, B(SE) = .001(.00), p < .001) was associated with age-adjusted shorter telomeres.

Linear regression analyses testing for associations of social support with LTL were performed, first adjusting for age, gender, race/ethnicity, SES, and the interaction of age with race, and age with gender (Model 1). Subsequent models in addition adjusted for health factors: BMI, pulse pressure, diabetes (Model 2), and lifestyle factors: smoking history, physical activity, and processed meat consumption (Model 3). As can be seen in Table 2, across the entire sample with ages ranging from 45–84, there were no significant associations of ESSI with LTL, F(1, 936) = .29, n.s. Further adjustments for health and lifestyle factors did not change this result.

Table 2.

Estimated mean differences (unstandardized Beta coefficient) in leukocyte telomere length in older and younger participants per unit increase in social support after adjustments by covariates

| Model 1 | Model 2: Further Adjustment for Health Factors | Model 3: Further Adjustment for Lifestyle Factors | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| B(SE) | β | p value | B(SE) | β | p value | B(SE) | β | p value | |

| Entire Sample (n = 948) | |||||||||

| ESSI (scale range: 5–25) | .001(.001) | .017 | .59 | .00(.001) | .012 | .70 | .00(.001) | .005 | .87 |

| Younger (<65 years old) | |||||||||

| ESSI (n = 547) | −.002(.001) | −.06 | .16 | −.002(.001) | −.06 | .14 | −.002(.001) | −.07 | .12 |

| Older (65+ years old) | |||||||||

| ESSI (n = 401) | .006(.002) | .15 | .002 | .005(.002) | .15 | .003 | .005(.002) | .13 | .007 |

Model 1: Adjusted for age (centered), gender, age X gender, age X race, education, income

Model 2: Adjusted for age (centered), gender, age X gender, age X race, education, income, body mass index, pulse pressure, diabetes

Model 3: Adjusted for age (centered), gender, age X gender, age X race, education, income, body mass index, pulse pressure, diabetes, smoking, physical activity, dietary intake of processed meats

B=Unstandardized Beta Coefficient, SE=Standard Error, β=Standardized Beta Coefficient

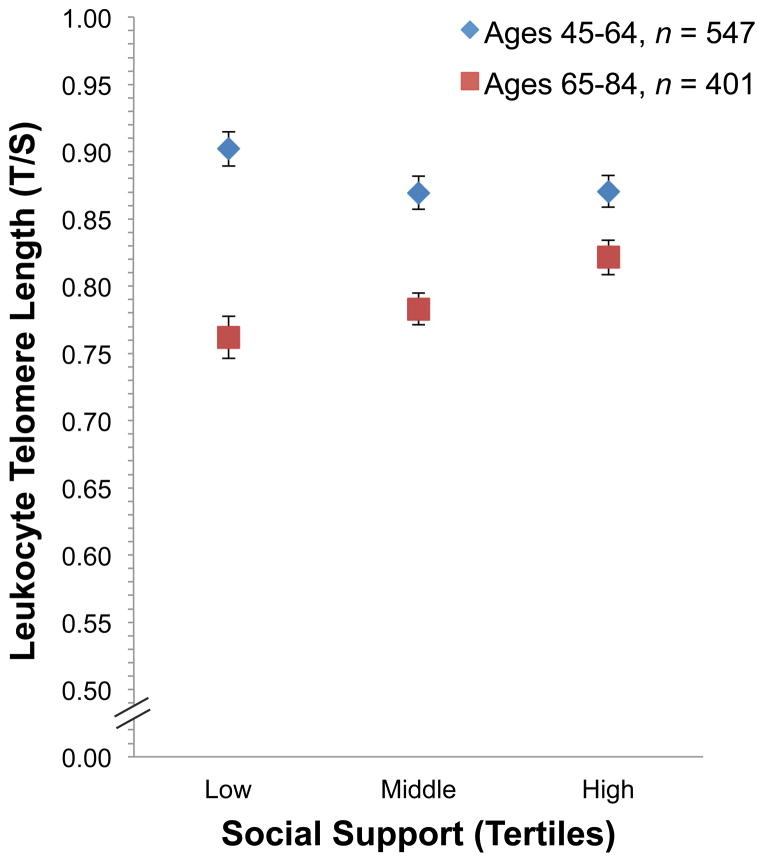

In line with our second hypothesis, we proceeded to test for a significant interaction of age with social support, predicting that older adults would show stronger associations of the ESSI with LTL than younger participants. The results of these analyses can be seen in Table 2. Addition of the interaction term Age (dichotomized) X ESSI to model 1 revealed that the interaction was significant, F(1,934) = 10.51, B(SE) = .008(.002), p = .001. Additional adjustments in models 2 (B(SE) = .007(.002), p = .002) and 3 (B(SE) = .007(.002), p = .002) did not reduce the significant interaction effect. Stratified by age, group analyses revealed there to be a significant association between social support and LTL in the older (65–84 years old) participants, F(1,383) = 7.41, R2 change = .017, p = .007, independent of other health and lifestyle risk factors. No significant association of social support with LTL was present in the younger group (45–64 years old), p = .12. A graphical representation of the interaction effect can be seen in Figure 1, where we report mean LTL values by tertile of social support within the two age categories. Among older participants, social support explained 1.7% of the variance in LTL when all other covariates were in the model. Moreover, with each unit decline in social support in the older group we observed a .005 decline in LTL, which is comparable to a one chronological year change in LTL in the current cohort sample. Secondary analyses were performed to test for an age by ESSI interaction with age as a continuous variable. Using Model 3 covariates the interaction of age (continuous) X ESSI was not statistically significant, B(SE) = .000(.00), p = .17.

Figure 1.

Mean leukocyte telomere length by tertile of social support and age category, corrected by all Model 3 covariates. The error bars denote standard error.

Discussion

Our results based on a racially/ethnically diverse community sample of men and women provide initial evidence that low social support is associated with shorter LTL in older adults (65–84 years old), but not in middle aged participants (45–64 years old), consistent with our hypothesis that the social environment may contribute to rates of cellular aging, particularly in late life when vulnerability to accelerated aging may be greater. Importantly, controlling for health risk factors and health behaviors that are thought to partially explain associations between psychosocial factors and health outcomes, failed to reduce the strength of the association between social support and LTL. These findings lend support to the hypothesis that social support is related to rates of cellular aging independent of common health risk markers and lifestyle.

Based on estimates of age effects on LTL derived from the same sample (i.e. T/S decline of −.005 per year estimated from entire cohort), the difference in LTL between the lowest and the highest tertile of social support amongst the older age group (mean score of 14 vs. 25) was equivalent to about 11 years of aging. These findings highlight a potential pathway through which limited social support contributes to disease initiation, progression, and premature death.

Mechanisms

In late life, there is a greater proportion of late differentiated immune cells resulting from a lifetime of exposures to multiple sources of stimulation (e.g. bacterial, viral, sympathetic nervous system) and subsequent proliferation. These older cells have unique biological characteristics, including alterations of cellular metabolic activity, a rise in reactive oxygen species production, and a decrease in antioxidant capacity, making them more vulnerable to further telomere erosion (14). In older adults, a greater proportion of leukocytes have short telomeres (24; 30), making later life a time of greater vulnerability to cellular dysfunction from aged cells. Here we report that low social support in later life is associated with shorter LTL. We posit that this association may reflect the impact of adverse social conditions on rates of cellular aging, and thus help explain links of social adversity to a number of adverse health outcomes (1; 4; 8).

There are several potential mechanisms through which social support in late life may offer protection from telomere erosion or through which limited social support might contribute to loss. Several researchers have reported cross-sectional associations between chronic psychological stress and shorter LTL (12; 33; 38; 54–56). Social support may act as a buffer to evaluations of threat, and thereby reduce the magnitude of the stress response to adverse conditions (8; 9). Only limited measures of psychological stress were available at MESA Exam 1 when the LTL measurement was performed, so we were unable to directly test this hypothesis. Low social support may also confer risk through contributing to elevated feelings of social isolation and loneliness which has biological consequences that parallel chronic stressor exposure (5; 57). It is well known that stress responses activate the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and sympatho-adrenal system, leading to the release of cortisol, epinephrine, and norepinephrine. These stress hormones signal a multitude of physiological changes that can increase inflammation (58–60) and oxidative stress (12; 61–64). These factors are primary contributors to telomere loss in leukocytes.

Telomerase, the enzyme that rebuilds telomeres, is also modified by stress hormones. Recent evidence reports a decline in telomerase activity upon cortisol exposure in vitro (65), an inverse association of telomerase with nocturnal urinary epinephrine, and lower telomerase activity in those with exaggerated cardiovascular responses to a stressful task (66). Importantly, telomerase is not only important for rebuilding telomeres, but can also protect older cells from entering senescence by capping the end of the chromosomes (21; 22). In late life this compromise in telomere capping may be more detrimental to health as there are greater proportions of late differentiated cells that are vulnerable to senescence. These senescent cells cause further damage to nearby cells and tissue (67), and in this way may further promote telomere erosion.

Study limitations and strengths

There are several limitations to these analyses. First, the cross-sectional nature of these analyses prevents us from inferring causal relations. Ideally studies should examine predictors of telomere change over time. Here, although social isolation in later life was associated with shorter LTL in this sample and this is compatible with greater attrition as a consequence of reduced social support, we cannot rule out the possibility that telomere erosion is associated with social support because it is a marker for chronic conditions causally linked to reductions in social support. For example, underlying morbidities and physical declines in functioning, which may be a consequence of or cause telomere loss, could drive individuals towards greater social withdrawal and thereby reductions in social support.

Given that cross-sectional associations of age with LTL estimate rates of shortening based on sample distribution rather than true longitudinal changes within individuals, our estimates of age effects on telomere erosion are bias and should therefore be interpreted with caution (68). Moreover, we cannot rule out the possibility that our age by social support interaction is due to a unique cohort effect. For example, it is possible that social support is more strongly associated with LTL in older than in younger cohorts not because of age per se but because of interactions of social support with early exposures (e.g. trauma from war/economic hardship/malnutrition), that may be patterned by birth cohort. Likewise, this investigation was conducted on a single sample and future work should seek to replicate this effect in an independent sample.

Another limitation of the present analyses is our measure of leukocyte telomere length. We cannot rule out the possibility that differences in a whole blood measure of telomere length is influenced by differences in the proportion of different types of white cell in circulation (e.g. % of neutrophils, T cells, etc.) given that these cell types can have different telomere lengths (69). If white blood cell differential is linked to social support, it may confound estimates of associations of social support with LTL. Furthermore, the present assessment of LTL captures telomere length across the leukocyte pool, which likely reflects circulating progenitor and hematopoietic stem cell telomere length, but it is less clear whether this blood measure represents whole system biological aging (70; 71).

Given that the cross validation of the ESSI with more substantial measures of social support were modest (r = .63) (50), our measure of social support undoubtedly includes some measurement error that could have affected our results. Future work should consider using more comprehensive measures of social support. It also seems plausible that the association of social support with LTL is due to unmeasured individual factors (e.g. personality characteristics that persist across the lifetime that are also associated with low social support). Likewise, given that depression has been associated with shorter LTL (39; 72), social support could be associated with LTL through history of depression, such that individuals with depression may alienate needed friends and family support. Future work should identify the causal path using longitudinal analyses. Strengths of the present analyses include the large and diverse population sampled with detailed risk factor measurement. In addition, the analyses statistically controlled for several risk factors with known associations with LTL, including health and lifestyle factors. We were able to document that associations between social support and LTL in older adults remained significant after adjustments for these factors.

Future directions

Further research examining the influence of socio-emotional adversity on premature cellular aging is warranted. Longitudinal investigations may help to answer the question of whether socio-emotional adversity might contribute to accelerated cellular aging that then increases risk for physical declines, disease initiation and progression, and premature mortality. Furthermore, as posited by our model of late life biobehavioral vulnerability to cellular senescence, these socio-emotional adversities may be particularly caustic in the later years of life. This increased vulnerability may be the result of altered cell behavior (e.g. increased inflammation, decreased telomerase activity, immune compromise) and altered neuroendocrine patterns, which have been observed in older individuals experiencing chronic stress (73; 74). Future research should focus on the consequences of neuroendocrine mediators on telomerase activity, gene transcription profiles, and inflammatory activity within these late differentiated cells, with particular emphasis on characterizing which cells relevant to disease processes are particularly vulnerable. Lastly, it is conceivable that our measure of social support was associated with LTL in later life because it is related to social conditions of the individual that have existed for many years, and it isn’t until late life that the cumulative biological wear and tear becomes evident. Future work should consider social support over longer periods of time to better estimate cumulative effects.

Summary

In sum, in a multi-site community sample of racially/ethnically diverse participants we found that social support in late life, but not in middle-aged participants, is positively associated with leukocyte telomere length, an indicator of cellular aging. To our knowledge, this is the first report of an association between social support and LTL, and suggests that telomere erosion may be a mechanism through which social isolation influences disease vulnerability and premature death in later life. These findings lend support to our model of late life biobehavioral vulnerability to cellular senescence, which postulates that older adults may be more susceptible to the biologically significant downstream effects of behavioral and socio-emotional factors because of the age of their biological system.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants R01 HL101161 (A.V.D-R.) and N01-HC 95159 through N01-HC 95169 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. The manuscript preparation was supported by grant T32-MH19925 from the National Institute of Mental Health, and the Cousins Center for Psychoneuroimmunology, UCLA (J.E.C.). The authors thank the other investigators, the staff, and the participants of the MESA study for their valuable contributions. A full list of participating MESA investigators and institutions can be found at http://www.mesa-nhlbi.org.

Abbreviations within text

- SS

Social Support

- LTL

Leukocyte Telomere Length

- B

Beta

- SE

standard error

- MESA

Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis

- SES

socioeconomic status, BMI, body mass index

- ENRICHD

Enhancing Recovery in Coronary Heart Disease

- ESSI

ENRICHD social support inventory

- qPCR

quantitative polymerase chain reaction

References

- 1.Seeman TE. Social ties and health: the benefits of social integration. Ann of Epidemiol. 1996;6:442–51. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(96)00095-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seeman TE. Health Promoting Effects of Friends and Family on Health Outcomes in Older Adults. The Science of Health Promotion. 2000;14:362–370. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-14.6.362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Layton JB. Social Relationships and Mortality Risk: A Meta-analytic Review. PLoS Medicine. 2010;7:e1000316. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carstensen LL, Fung HH, Charles ST. Socioemotional selectivity theory and the regulation of emotion in the second half of life. Motivation and Emotion. 2003;27:103–123. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cole SW, Hawkley LC, Arevalo JM, Sung CY, Rose RM, Cacioppo JT. Social regulation of gene expression in human leukocytes. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R189. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-9-r189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pressman SD, Cohen S, Miller GE, Barkin A, Rabin BS, Treanor JJ. Loneliness, social network size, and immune response to influenza vaccination in college freshmen. Health Psych. 2005;24:297–306. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.3.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohen S, Doyle WJ, Skoner DP, Rabin BS, Gwaltney JM. Social ties and susceptibility to the common cold. JAMA. 1997;277:1940–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cacioppo JT, Hawkley LC. Social isolation and health, with an emphasis on underlying mechanisms. Perspect Biol Med. 2003;46:S39–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cohen S, Wills TA. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol Bull. 1985;98:310–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kananen L, Surakka I, Pirkola S, Suvisaari J, Lönnqvist J, Peltonen L, Ripatti S, Hovatta I. Childhood adversities are associated with shorter telomere length at adult age both in individuals with an anxiety disorder and controls. PloS one. 2010;5:e10826. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O’Donovan A, Lin J, Dhabhar FS, Wolkowitz O, Tillie JM, Blackburn E, Neylan TC. Pessimism correlates with leukocyte telomere shortness and elevated interleukin-6 in post-menopausal women. Brain Behav Immun. 2009;23:446–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2008.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Epel E, Blackburn E, Lin J, Dhabhar F, Adler N, Morrow J, Cawthon RM. Accelerated telomere shortening in response to life stress. PNAS. 2004;101:17312–17315. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407162101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.von Zglinicki T. Oxidative stress shortens telomeres. Trends Biochem Sci. 2002;27:339–344. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(02)02110-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sahin E, Colla S, Liesa M, Moslehi J, Müller FL, Guo M, Cooper M. Telomere dysfunction induces metabolic and mitochondrial compromise. Nature. 2011;470:359–365. doi: 10.1038/nature09787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Erusalimsky JD. Vascular endothelial senescence: From mechanisms to pathophysiology. J of Applied Physiol. 2009;106:326–32. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.91353.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Minamino T. Endothelial Cell Senescence in Human Atherosclerosis: Role of Telomere in Endothelial Dysfunction. Circulation. 2002;105:1541–1544. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000013836.85741.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Effros RB. The role of CD8 T cell replicative senescence in human aging. Immunol Rev. 2005;205:147–57. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burton DG. Cellular senescence, ageing and disease. Age. 2009;31:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s11357-008-9075-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Houben JMJ, Moonen HJJ, van Schooten FJ, Hageman GJ. Telomere length assessment: Biomarkers of chronic oxidative stress? Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;44:235–246. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jiang H, Ju Z, Rudolph KL. Telomere shortening and ageing. Z Gerontol Geriat. 2007;40:314–324. doi: 10.1007/s00391-007-0480-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blackburn EH. Telomeres and telomerase: their mechanisms of action and the effects of altering their functions. FEBS Letters. 2005;579:859–62. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blackburn EH. Telomere states and cell fates. Nature. 2000;408:53–6. doi: 10.1038/35040500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ehrlenbach S, Willeit P, Kiechl S, Willeit J, Reindl M, Schanda K, Kronenberg F, Brandstatter A. Influences on the reduction of relative telomere length over 10 years in the population-based Bruneck Study: introduction of a well-controlled high-throughput assay. Int J Epidemiol. 2009;38:1725–34. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyp273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Calado RT, Young NS. Telomere diseases. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2353–65. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0903373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fülöp T, Franceschi C, Hirokawa K. Handbook on Immunosenescence: Basic Understanding and Clinical Applications. Springer; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 26.De Martinis M, Franceschi C, Monti D, Ginaldi L. Inflamm-ageing and lifelong antigenic load as major determinants of ageing rate and longevity. FEBS letters. 2005;579:2035–9. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.02.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Franceschi C, Bonafe M, Valensin S, Olivieri F, De Luca M, Ottaviani E, De Benedictis G. Inflamm-aging: An Evolutionary Perspective on Immunosenescence. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;908:244–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06651.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Effros RB, Boucher N, Porter V, Zhu X, Spaulding C, Walford RL, Kronenberg M, Cohen D. Decline in CD28+ T cells in centenarians and in long-term T cell cultures: a possible cause for both in vivo and in vitro immunosenescence. Exp Gerontol. 1994;29:601–9. doi: 10.1016/0531-5565(94)90073-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Effros RB. Telomere/telomerase dynamics within the human immune system: Effect of chronic infection and stress. Exp Gerontol. 2011;46:135–40. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2010.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Frenck RW, Blackburn EH, Shannon KM. The rate of telomere sequence loss in human leukocytes varies with age. PNAS. 1998;95:5607–10. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.10.5607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Farzaneh-Far R, Cawthon RM, Na B, Browner WS, Schiller NB, Whooley MA. Prognostic value of leukocyte telomere length in patients with stable coronary artery disease: data from the Heart and Soul Study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:1379–84. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.167049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Epel ES, Merkin SS, Cawthon R, Blackburn EH, Adler NE, Pletcher MJ, Seeman TE. The rate of leukocyte telomere shortening predicts mortality from cardiovascular disease in elderly men. Aging. 2009;1:81–8. doi: 10.18632/aging.100007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Damjanovic A, Yang Y, Glaser R, Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Nguyen H, Laskowski B, Zou Y, Beversdorf DQ, Weng N. Accelerated telomere erosion is associated with a declining immune function of caregivers of Alzheimer’s disease patients. J Immunol. 2007;179:4249–4254. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.6.4249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aubert G, Lansdorp PM. Telomeres and aging. Physiological reviews. 2008;88(2):557–79. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00026.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Falls Among Older Adults: An Overview. Retrieved June 12, 2012 from http://www.cdc.

- 36.Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Preacher KJ, MacCallum RC, Atkinson C, Malarkey WB, Glaser R. Chronic stress and age-related increases in the proinflammatory cytokine IL-6. PNAS. 2003;100:9090–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1531903100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lung F-W, Chen NC, Shu B-C. Genetic pathway of major depressive disorder in shortening telomeric length. Psychiatr Genet. 2007;17:195–9. doi: 10.1097/YPG.0b013e32808374f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Simon NM, Smoller JW, McNamara KL, Maser RS, Zalta AK, Pollack MH, Nierenberg AA, Fava M, Wong K-K. Telomere shortening and mood disorders: preliminary support for a chronic stress model of accelerated aging. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60:432–5. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hoen PW, de Jonge P, Na BY, Farzaneh-Far R, Epel E, Lin J, Blackburn E, Whooley MA. Depression and Leukocyte Telomere Length in Patients With Coronary Heart Disease: Data From The Heart and Soul Study. Psychosom Med. 2011;73:524–7. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31821b1f6e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Diez Roux AV, Ranjit N, Jenny NS, Shea S, Cushman M, Fitzpatrick A, Seeman T. Race/ethnicity and telomere length in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Aging Cell. 2009;8:251–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2009.00470.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bild DE. Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis: Objectives and Design. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156:871–881. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aviv A, Chen W, Gardner JP, Kimura M, Brimacombe M, Cao X, Srinivasan SR, Berenson GS. Leukocyte telomere dynamics: Longitudinal findings among young adults in the Bogalusa Heart Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;169:323–9. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cherkas LF, Aviv A, Valdes AM, Hunkin JL, Gardner JP, Surdulescu GL, Kimura M, Spector TD. The effects of social status on biological aging as measured by white-blood-cell telomere length. Aging Cell. 2006;5:361–365. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2006.00222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fitzpatrick AL, Kronmal RA, Gardner JP, Psaty BM, Jenny NS, Tracy RP, Walston J, Kimura M, Aviv A. Leukocyte telomere length and cardiovascular disease in the cardiovascular health study. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165:14–21. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jeanclos E, Schork NJ, Kyvik KO, Kimura M, HJ, Aviv A, Skurnick JH. Telomere length inversely correlates with pulse pressure and is highly familial. Hypertension. 2000;36:195–200. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.36.2.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cherkas LF, Hunkin JL, Kato BS, Richards JB, Gardner JP, Surdulescu GL, Kimura M, Lu X, Spector TD, Aviv A. The association between physical activity in leisure time and leukocyte telomere length. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:154–8. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2007.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nettleton JA, Diez-Roux A, Jenny NS, Fitzpatrick AL, Jacobs DR., Jr Dietary patterns, food groups, and telomere length in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) Am J of Clin Nutr. 2008;88:1405–12. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.26429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Golden SH, Lee HB, Schreiner PJ, Roux AD, Fitzpatrick AL, Szklo M, Lyketsos C. Depression and type 2 diabetes mellitus: the Multiethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Psychosom Med. 2007;69:529–36. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3180f61c5c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lemelin ET, Diez Roux AV, Franklin TG, Carnethon M, Lutsey PL, Ni H, O’Meara E, Shrager S. Life-course socioeconomic positions and subclinical atherosclerosis in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68:444–51. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.10.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mitchell PH, Powell L, Blumenthal J, Norten J, Ironson G, Pitula CR, Froelicher ES, Czajkowski S, Youngblood M, Huber M, Berkman LF. A short social support measure for patients recovering from myocardial infarction: the ENRICHD Social Support Inventory. J Cardiopulm Rehabil. 2003;23:398–403. doi: 10.1097/00008483-200311000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mezuk B, Diez Roux AV, Seeman T. Evaluating the buffering vs. direct effects hypotheses of emotional social support on inflammatory markers: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Brain Behav Immun. 2010;24:1294–300. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2010.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cawthon RM. Telomere measurement by quantitative PCR. Nucleic Acids Research. 2002;30:47e–47. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.10.e47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Diez Roux AV, Ranjit N, Jenny NS, Shea S, Cushman M, Fitzpatrick A, Seeman T. Race/ethnicity and telomere length in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Aging Cell. 2009;8:251–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2009.00470.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Gouin J-P, Weng N-P, Malarkey WB, Beversdorf DQ, Glaser R. Childhood Adversity Heightens the Impact of Later-Life Caregiving Stress on Telomere Length and Inflammation. Psychosom Med. 2010;22:16–22. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31820573b6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Parks CG, Miller DB, McCanlies EC, Cawthon RM, Andrew ME, DeRoo LA, Sandler DP. Telomere length, current perceived stress, and urinary stress hormones in women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers. 2009;18:551–60. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Drury SS, Theall K, Gleason MM, Smyke aT, De Vivo I, Wong JYY, Fox NA, Zeanah CH, Nelson CA. Telomere length and early severe social deprivation: linking early adversity and cellular aging. Mol Psychiatry. 2011 doi: 10.1038/mp.2011.53. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT. Loneliness and pathways to disease. Brain Behav Immun. 2003;17 (Suppl 1):S98–105. doi: 10.1016/s0889-1591(02)00073-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Black PH, Garbutt LD. Stress, inflammation and cardiovascular disease. J Psychosom Res. 2002;52:1–23. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(01)00302-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Steptoe A, Hamer M, Chida Y. The effects of acute psychological stress on circulating inflammatory factors in humans: a review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav Immun. 2007;21:901–912. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Irwin MR, Cole SW. Reciprocal regulation of the neural and innate immune systems. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2011;11:625–32. doi: 10.1038/nri3042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Robles TF, Carroll JE. Restorative biological processes and health. Soc Personal Psychol Compass. 2011;5:518–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2011.00368.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sahin E, Gümüşlü S. Immobilization stress in rat tissues: alterations in protein oxidation, lipid peroxidation and antioxidant defense system. Comp Biochem Physiol C Toxicol Pharmacol. 2007;144:342–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpc.2006.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Srivastava S, Chandrasekar B, Gu Y, Luo J, Hamid T, Hill BG, Prabhu SD. Downregulation of CuZn-superoxide dismutase contributes to beta-adrenergic receptor-mediated oxidative stress in the heart. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;74:445–55. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Flint MS, Baum A, Chambers WH, Jenkins FJ. Induction of DNA damage, alteration of DNA repair and transcriptional activation by stress hormones. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2007;32:470–9. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2007.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Choi J, Fauce SR, Effros RB. Reduced telomerase activity in human T lymphocytes exposed to cortisol. Brain Behav Immun. 2008;22:600–5. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Epel ES, Lin J, Wilhelm FH, Wolkowitz OM, Cawthon R, Adler NE, Dolbier C, Mendes WB, Blackburn EH. Cell aging in relation to stress arousal and cardiovascular disease risk factors. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2006;31:277–87. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2005.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Campisi J. Senescent cells, tumor suppression, and organismal aging: Good citizens, bad neighbors. Cell. 2005;120:513–22. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jacobs DR, Hannan PJ, Wallace D, Liu K, Williams OD, Lewis CE. Interpreting age, period and cohort effects in plasma lipids and serum insulin using repeated measures regression analysis: the CARDIA Study. Stat Med. 1999;18:655–79. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19990330)18:6<655::aid-sim62>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Weng N. Interplay between telomere length and telomerase in human leukocyte differentiation and aging. J Leukoc Biol. 2001;70:861–867. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Aviv A. Leukocyte telomere length: The telomere tale continues. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89:1857–63. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.27807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Aviv A. Genetics of leukocyte telomere length and its role in atherosclerosis. Mutat Res. 2012;730:68–74. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wolkowitz OM, Mellon SH, Epel ES, Lin J, Dhabhar FS, Su Y, Reus VI, Rosser R, Burke HM, Kupferman E, Compagnone M, Nelson JC, Blackburn EH. Leukocyte telomere length in major depression: correlations with chronicity, inflammation and oxidative stress--preliminary findings. PloS One. 2011;6:e17837. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Heffner KL. Neuroendocrine effects of stress on immunity in the elderly: implications for inflammatory disease. Immunology and allergy clinics of North America. 2011;31(1):95–108. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2010.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gouin JP, Hantsoo L, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. Immune dysregulation and chronic stress among older adults: a review. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2008;15(4–6):251–9. doi: 10.1159/000156468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]