Abstract

The FHA domain is a phospho-peptide binding module involved in a wide range of cellular pathways, with a striking specificity for phospho-threonine over phospho-serine binding partners. Biochemical, structural, and dynamic simulations analysis allowed Pennell and colleagues to unravel the molecular basis of FHA domain phospho-threonine specificity.

Intracellular signaling processes that mediate key cellular events such as the cell cycle and the response to DNA damage critically rely on cascades of serine/threonine protein phosphorylation. Ser/Thr phosphorylation drives interactions between proteins through the recognition of the phosphorylated peptide by a number of distinct protein domains that exhibit an impressive degree of selectivity for the sequence of the peptide target (Yaffe and Smerdon, 2004). Perhaps one of the most intriguing aspects of phospho-peptide binding specificity is the ability of certain domains to distinguish between phospho-serine (pSer) and phospho-threonine (pThr) in the peptide. The most dramatic example is found in the family of FHA domains, which all exhibit a profound selectivity for pThr over pSer-containing phospho-peptides. In this issue of Structure, Pennell et al. (2010) use a combination of crystallo-graphic, biochemical, and computational approaches to provide a detailed structural mechanism for this selectivity, which is likely conserved throughout the FHA protein family.

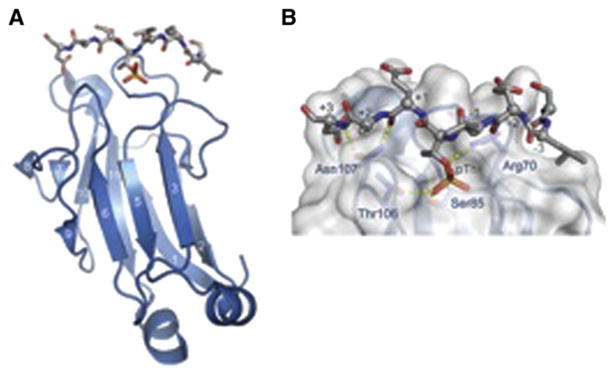

FHA, or forkhead-associated, domains, initially identified in the forkhead family of transcription factors, are found in both prokaryotic and eukaryotic organisms (Hofmann and Bucher, 1995). The role of the FHA as a phospho-peptide binding domain was first revealed in studies of the FHA domains of the S. cerevisiae DNA damage signaling kinase, Rad53p (Durocher et al., 1999, 2000). These studies revealed that both FHA domains within Rad53p could independently bind phospho-peptides with marked specificity for the identity of the side chain three residues C-terminal to the site of phosphorylation. Intriguingly, they also showed a dramatic preference for pThr over pSer peptides. While these binding specificities appear to be common in other members of the FHA family, certain unique preferences have also been observed (Liang and Van Doren, 2008; Mahajan et al., 2008). For example, a subfamily of the FHA domains, first identified within the DNA repair protein polynucleotide kinase, recognize highly acidic peptide targets, often containing multiple sites of phosphorylation (Ali et al., 2009). Structural studies on FHA domains have revealed a common architecture consisting of an 11-stranded β sandwich. The phosphorylated peptide binds three different loops that protrude from one end of the β sandwich (β4-β5, β6-β7, and β10-β11) (Figure 1A). The only two conserved residues of these loops, an Arg and a Ser, provide two of the ligands for the phosphate group, while additional ligands are provided by other less well-conserved residues (Figure 1B). In addition, a second shallow pocket serves to provide binding specificity for the amino acid at the +3 position with respect to the pThr.

Figure 1. Structure of the Rad53p FHA Bound to a Cognate pThr-Containing Peptide.

(A) Overview of the Rad53p FHA phospho-peptide complex.

(B) Detailed view of FHA phospho-peptide interactions, highlighting key residues that contact the pThr and downstream residues in the phospho-peptide target.

In this issue, Pennell et al. (2010) probe the basis for pThr-dependent FHA interactions through the study of the FHA domain of Mycobacterium tuberculosis Rv0020c. They use oriented peptide library screening to select peptides that bind this previously uncharacterized domain with high affinity, revealing a significant preference for pThr peptides containing a small/medium hydrophobic residue at the pThr +3 position. The thermodynamic contributions of specific residues to binding energetics were probed by isothermal titration calorimetric peptide-binding measurements of an extensive set of peptide and FHA mutants. These experiments further support the importance of the pThr +3 residue and reveal an energetic coupling of the peptide +3 residue with the pThr −1 residue. They went on to determine the structure of the Rv0020c FHA domain, both free and in complex with an optimal phopho-peptide target. Building on this high resolution structural data, they used molecular dynamics simulations to specifically address the mechanism of selective recognition of pThr- versus pSer-containing peptides. The simulations indicate that while binding of either the pThr or pSer peptide induces a significant stabilization of the FHA, the effect is much more pronounced for the pThr peptide. The pThr-dependent stabilization relies upon limited contacts between the pThr γ-methyl group and a small pocket on the FHA composed of residues including a highly conserved asparagine residue (Asn495 in Rv0020c), which makes critical contacts to the phospho-peptide backbone bridging the +1 and +3 residues. Loss of this contact in the complex with the pSer peptide results in a higher degree of overall flexibility, in particular in the regions directly in contact with the pSer as well as Asn495. Taken together, this work presents a satisfying explanation for how the loss of a small van der Waals contact surface can trigger the destabilization of the entire FHA-peptide interface, a mechanism that is likely conserved throughout the FHA protein family.

We are beginning to understand the detailed mechanisms of phospho-peptide binding specificity for many of the critical protein modules that regulate intracellular signaling pathways. While additional details remain to be ironed out—for example, how certain BRCT domains selectively bind pSer- over pThr-peptides (Manke et al., 2003)—ultimately we will need to understand the impact of these interactions on the intact protein complexes that regulate phosphorylation-dependent signaling.

This is a commentary on article Pennell S, Westcott S, Ortiz-Lombardía M, Patel D, Li J, Nott TJ, Mohammed D, Buxton RS, Yaffe MB, Verma C, Smerdon SJ. Structural and functional analysis of phosphothreonine-dependent FHA domain interactions. Structure. 2010 Dec 8;18(12):1587-95.

References

- Ali AA, Jukes RM, Pearl LH, Oliver AW. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:1701–1712. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn1086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durocher D, Henckel J, Fersht AR, Jackson SP. Mol Cell. 1999;4:387–394. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80340-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durocher D, Taylor IA, Sarbassova D, Haire LF, Westcott SL, Jackson SP, Smerdon SJ, Yaffe MB. Mol Cell. 2000;6:1169–1182. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00114-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann K, Bucher P. Trends Biochem Sci. 1995;20:347–349. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)89072-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang X, Van Doren SR. Acc Chem Res. 2008;41:991–999. doi: 10.1021/ar700148u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahajan A, Yuan C, Lee H, Chen ES, Wu PY, Tsai MD. Sci Signal. 2008;1 doi: 10.1126/scisignal.151re12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manke IA, Lowery DM, Nguyen A, Yaffe MB. Science. 2003;302:636–639. doi: 10.1126/science.1088877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennell S, Westcott S, Ortiz-Lombardia M, Patel D, Li J, Nott TJ, Mohammed D, Buxton RS, Yaffe MB, Verma C, Smerdon S. Structure. 2010;18:1587–1595. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2010.09.014. this issue. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaffe MB, Smerdon SJ. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2004;33:225–244. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.33.110502.133346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]